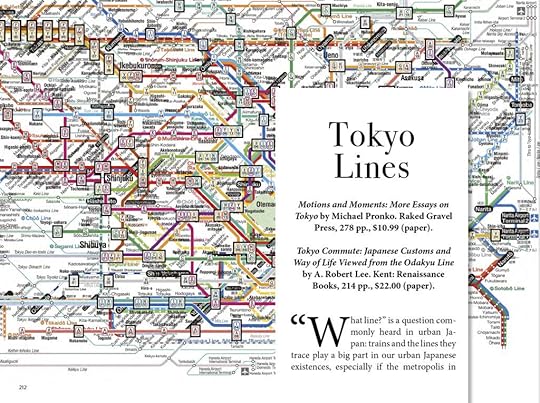

Michael Pronko's Blog, page 14

May 9, 2017

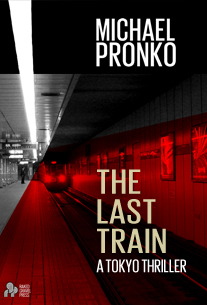

Interview about The Last Train

The Interview: Bookbag Talks To Michael Pronko About ”The Last Train”

Summary: Sue was very impressed by The Last Train, a thriller set in Tokyo. she had quite a few questions for author Michael Pronko when he popped into Bookbag Towers.

Date: 9 May 2017

Interviewer: Sue Magee

Share on:

Sue was very impressed by The Last Train, a thriller set in Tokyo. She had quite a few questions for author Michael Pronko when he popped into Bookbag Towers.

Bookbag: When you close your eyes and imagine your readers, who do you see?

Michael Pronko: I see all sorts of people. Whenever I talk about mysteries or thrillers, people often sheepishly confess how much they love reading them. All novels are mysteries in some sense. I see readers interested in Tokyo or Japanese culture, since Tokyo is a big mystery, or millions of small mysteries. Thrillers and mysteries are very ethical at their core, despite the awful things that happen. So, I think people who are mystery readers have a sharp sense of justice and maybe a need to see things set right, even when they can’t be. I also see readers who just love a great story.

BB: We’ve always been impressed by your non-fiction pieces on Tokyo. What inspired you to turn to fiction?

MP: I love writing both, but with the novel, I wanted to work inside a larger frame to create new kinds of connections between ideas, images, places and characters. In the non-fiction pieces, I’m always there reflecting on what’s happening, on what I see. So, with fiction, I can take myself out of the writing to see through another character’s eyes. I was also interested in taking readers (and myself) into the concealed interiors of Japanese culture. Much of Tokyo is hidden away. I can go to those secret places in non-fiction, too, of course, but fiction has more potential to explore and examine the veiled sides of Tokyo life. I’ve always written fiction, just not published much of it, so in a way, it’s turning back to fiction.

BB: Which do you find more difficult to write – fiction or non-fiction? Does your writing overlap at all?

MP: I find fiction is an expansion of experience and non-fiction a condensation of experience. Fiction makes broader connections and non-fiction makes focused connections. The two forms of writing are two ways of ordering and examining the world around me, two different lenses, two different writing challenges. I’m not sure which is harder ultimately, but for me, they feed off each other. Many passages in fiction, especially description and exposition, could be non-fiction, and non-fiction employs fictional elements, like three-part dramatic structure, irony, dialogue, or symbolism. They overlap tremendously. It’s not the parts that differ, but the whole.

BB: I loved Detective Hiroshi! Will we meet him again? What was the inspiration behind him?

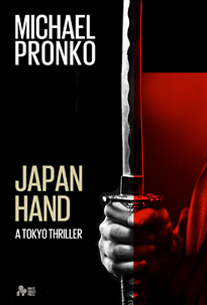

MP: Yeah, he’s this likeable guy, a little lonely, very demure, but with tremendous energy, well-honed talents, and a strong sense of what’s right and wrong. Because of his experience outside Japan, he’s divided between his internationalized mindset and the traditional array of Japanese feelings and attitudes. I often sense this unresolved divide inside many Japanese. Hiroshi’s different from the other two detectives who are more “purely” Japanese. Sakaguchi, the sumo wrestler, all instinct and brawn, knows who he is. Takamatsu is the old-style Japanese male who does whatever he wants because he can, always sure of himself, too sure, it turns out. You will meet all of them again in the upcoming books, Japan Hand and Thai Girl in Tokyo.

BB: Your love of your adopted city shines through the story, but at one point you say that ‘Tokyo’s a strange, lonely wacko place’. Is that how it feels to you?

MP: In the novel, the American guy who is escaping Tokyo says that at the airport. I feel that way sometimes at the airport, too, going in AND going out! But, living here, it all starts to make sense in a way, so I would not say it’s wacko. Some things are still strange to me, but I like that sense of strangeness. I find a little discomfort energizing, and motivating. Tokyo is a very lonely place, though, and that’s what many scenes express. Tokyo is a split way of life where you are massed into large groups, on the train, at work, in social outings, but you still spend a lot of time alone. Maybe that’s the wacko side?

BB: The men who move the boxes from Hiroshi’s apartment are described as ‘displaying the self-respect Japanese accorded all jobs, high or low’. Is this a particularly Japanese trait? Do you think the western world would do well to copy it?

MP: Yes, I think that’s a great attitude and very Japanese. In the West, many people lose the sense of self-respect that comes from work. I think in the west people should respect other people’s work more, whatever they’re doing. It’s amazing the level of service in Japan, and it comes from performing whatever job with dignity. You expect people to do their job, but you thank them for even the smallest of things. Japanese have a sense of duty, to do what they should do, even if that’s something—like wiping tables or wrapping a package—that seems trivial. It’s a form of mutual respect that pervades all public interactions in Japan.

BB: You describe real estate in Tokyo as being some of the most expensive in the world. Does this create problems for Japanese workers?

MP: It creates problems for everyone who doesn’t own any! This is the core social and economic conflict of the novel. Real estate became a dominant form of power during the bubble years of the 1990s when prices went sky high. But even after the economy slid into recession, owning real estate was still the great social divide. Things are spatially cramped in Tokyo, so you will see even small plots of land, I mean like arms-width, being turned into a store or a three-story house. Space is just always this calculation about everything. It drives the economy, not always in good directions. It’s a basic desire, because it’s so in demand, and so hard to get. That’s why Michiko in the novel is so unusual, because she figures this out and acts on it. She’s not satisfied accepting her land-less life.

BB: Your descriptions of Japanese food made my mouth water. What would be your perfect meal?

MP: I love having a bowl of ramen noodles by myself along a long counter in a steamy noodle restaurant. But I think “the” perfect meal is with friends, talking, eating, drinking. It starts with light vegetable dishes and tofu and proceeds to a plate of raw fish (sashimi) served on ice. From there, I order yakitori, a succession of grilled chicken and vegetable skewers, followed by grilled fish or deep-fried chicken. And I always order something I don’t know, some strange, seasonal, unknown thing. Wash it all down with cold sake. At the end, chazuke, which is green tea with rice, nori, and a sliver of salty fish. Puts you right to sleep. Perfect.

BB: You’re a university professor and you teach a wide variety of subjects. How do you find the time to write?

MP: I wonder myself. I’d love more time to write, but I feel teaching feeds into writing and vice versa. My students keep the reading side of literature alive for me. It’s so fresh and first-time for them. Outlining a novel to prep for my seminar is learning to write. When we work on a poem in class, it heightens both my students’ and my feel for the power of language. With the films I teach, my students and I work on outlines together before discussing characters, conflicts and themes. All that feeds into writing. And it flows in the other direction. Writing novels allows me to better help students understand how novels work and what they mean. William Carlos Williams said he couldn’t have been a poet without being a doctor, and vice versa. I take his attitude as good, solid advice. It’s less conflict than confluence. Most of the time, anyway.

BB: What’s next for Michael Pronko?

MP: Two more novels in the same Hiroshi series are penned and drafted, but not polished and finalized. The next one, Japan Hand, focuses on Japan’s relationship with America, especially the military bases. It features a great main character who is, unfortunately, dead from the beginning, and digs into US-Japan relations. The next after that, Thai Girl in Tokyo, looks at the world of teenagers, prostitution and pornography. It features two fantastic women characters on the lam, one a vibrant Thai girl and the other a street-smart Japanese teen. And some non-fiction, too. I’ll be in the U.S. for several months this year to do research, and will gather notes for a non-fiction book about Japan and America, a side-by-side cultural consideration. When I get back, I’ll focus on a non-fiction book on Japanese cultural objects.

BB: There’s lots to look forward to there, Michael. Thank you for taking the time to talk to us.

You can read more about Michael Pronko here.

May 3, 2017

April 24, 2017

April 19, 2017

The Last Train–a Tokyo thriller May 31st!

After a trilogy of first-person, memoir-like essays about life in Tokyo, I have been writing a new series of thrillers set in Tokyo—the Hiroshi series. Tokyo is an intense place for everyone, and for Hiroshi Shimizu, a novice detective, it gets even more intense.

In the first in the series, The Last Train, Hiroshi teams up with ex-sumo wrestler Sakaguchi to scour Tokyo’s hostess clubs, sacred temples, skyscraper offices and industrial wastelands to find an elusive killer who masks homicide as suicide. By train.

After years in America and lost in neat, clean spreadsheets, Hiroshi pushes himself out of his office and into the grim realities of the biggest city in the world. He’s determined to cut through Japan’s ambiguities—and dangers—to find the murderous ex-hostess before she extracts her final revenge—which just might be him.

Next in the series is Japan Hand, where Hiroshi encounters a katana-wielding killer responsible for the death of an American statesman, and old Japan hand, who became entangled in East Asian diplomacy, or lack thereof.

The third thriller in the Tokyo series, Thai Girl in Tokyo, follows the escape of a 15-year-old Thai girl, Sukanya, from her tormentors when she sees too much. Sukanya gets help from a streetwise Japanese teen, Misaki, to find revenge and to get back home. Check back here for updates and release dates.

Hiroshi is a fascinating character who lived outside Japan for years, and now sees his home country and city in a different way. As he learns more about the inside of homicide, he starts seeing everything in a different way.

Hiroshi is a fascinating character who lived outside Japan for years, and now sees his home country and city in a different way. As he learns more about the inside of homicide, he starts seeing everything in a different way.

April 7, 2017

Beauty Blossoming

Cherry blossoms must be the most written about flower in history, and certainly the most photographed. But since thousands of people, perhaps millions in Japan, keep taking photos, I suppose writers can keep writing about them, too.

I walked through Shinjuku Gyoen Park the other day. Even on a cloudy, windy Thursday afternoon, the elegant walkways were packed. It was impossible to find any line of sight to take a photo without strangers cramming the frame. What other flower is so loved that everyone photobombs everyone else, and just shrugs and smiles about it?

One answer is that cherry trees are already popular. But they’re popular not in the way of some music video promoted by a corporate ad account, but naturally popular. Like rice. Like smiling. They have a natural appeal that needs little promotion. PR companies must be envious. Cherry trees are everywhere in Tokyo and only advertise themselves.

Another reason is that cherry trees seem so alive. They have an individuality, a flexibility, and somehow hold a relation to humanity that make them easy to love. The long low branches bend down to the ground as if meeting us earth-bound humans halfway. The higher branches urge us upward, away from ourselves. Each cherry tree is a meeting, and a journey.

Cherry trees also look good set against other trees, and actually, set against anything. They go well with all shades of green, and every color of sky. The soft, puffed petals go nicely against the sharp spikes of pine tree needles, and bowl over the other shrubs, bushes and trees that dare to flower at the same time.

Cherry trees look great set against water–ponds or rivers or moats. The small petals floating on top turn the murky water into a pedestal for their tiny beauty. Cherry trees even light up the dirt, packed down from years, decades, centuries of passersby and drinking parties. Even the trees planted on dividers inside a driving school’s practice course near my house look good against the concrete and learner cars.

I love watching people taking photos of people as they nestle themselves visually into the blossoms. At the park the other day, an old woman with a cane vainly plumped and pulled her hair, not too old to want to look good. She scolded her husband for not getting a good shot. Kids posed for a few seconds, then ran off to play tag, ride piggyback and yell and laugh a little wilder than usual. A couple of kids blew soap bubbles, normally mesmerizing, but the bubbles couldn’t compete with the petals.

The foreigners walking with camera gear in hand looked stunned. Their multicultural “wow’s” quickly ran out of energy, even if their fingers kept pressing the shutter button. They seemed to slip into a sort of awed contemplation of what is so obviously a simple, great idea—planting cherry trees all over the place.

Another part of their appeal is how well cherry trees dance. They are always in motion. The outer branches flex in the lightest breeze and with just the right looseness, like a young, limber dancer. They sway and bounce and shake off petals in the wind, a few at a time, bending far before recoiling, the limbs sprightly.

The trunks, though, have nothing of youth. They are ancient, deep-rooted, gnarled and mossed over. The trunks look like several trunks cobbled together. They twist at unexpected junctures and thicken, bulge or break off. Unlike the youthful upper limbs, the trunks of cherry trees show t

he struggle of their growth, the stages of their upward crawl over the years, better with every year.

The color is intense. The white, or pink but mostly white, forms a pointillist mirage. Your eyes and your mind fill in the open spaces between the dots of petals. The dots of white are more exciting than solid white would be, perhaps because the mind connects them to create a color that is less there than imagined. The dappled white shifts from glossier to flatter to electric, from darker to greener to whiter as the sunlight changes through the clouds coming in at new angles. When the clouds recede, the color is almost painful.

People always pile up at the prettiest trees, so there was no hope of getting an individual shot that day. I noticed people took an extra minute to prepare in front of the prettiest ones, as if they felt the need to look just right when the background was so spectacular. Those taking the photos looked up and down and around, as if distracted from the face of their lover, family member or friend by the flowers around them. Those taking selfies wiggled back and forth, careful to position themselves just right.

And though every cherry tree is photo-ready, people always packing around the fullest, most perfectly blossoming trees makes me wonder if there is such a thing as universal beauty. A glance around at the couples seems to suggest everyone has their own taste in what’s good-looking in the human realm. But with the cherry trees, everyone seems to agree on which ones are best, flocking there like birds to a feeder, carp to crumbs tossed in the pond.

Standing there being photographed, it’s as if for a moment, we touch the most sublime beauty. We feed off it. We want to take a photo with that, to wrap ourselves in it, and be as close as we can for the moment posing and for the forever posed. We take away more than a good shot or two. We take away beauty.

Then, we shake ourselves free, check the camera screen, glance at the tree, and the other people, and walk on, knowing the trees are behind us now as we turn to our other concerns, and knowing, too, we can stand in front of the cherry trees again next year when they’ll have grown even more intense and impressive and beautiful, urging us to do the same. (April 8, 2017)

March 25, 2017

Bone Sake

I’ve eaten plenty of fish bones during my time in Asia, most still inside the fish but others taken out like a sheet and deep-fried until they become crisp as potato chips and just as chomp-able. I don’t enjoy fish bones like some people do, and tend to order boneless pieces when I have the choice. But on occasion I don’t mind chewing fish meat with bones inside if the taste is good enough to overcome the boniness, that is, if there’s texture, taste or another pleasure involved.

But with a drink I ordered at a cozy, old-style izakaya in Ogikubo, the boniness seemed to be the entire goal, as if all the other fish flavors had been stripped away and what was left was the pure, direct taste of bone. After decades of eating and drinking anything set before me, I wondered if I had at last hit some cultural wall?

Japanese food is varied and complex enough that I often order things out of curiosity after seeing it cross the restaurant in the hands of the wait staff. “What’s that?” I’ll whisper when they come to my table, or I’ll search the menu for the never-seen-before dish and just order it. But this time, half-joking and half-adventurous, I looked at the hand-written sign for “bone sake” hanging on the wall—two simple characters: bone and alcohol—and thought: What could go wrong? My wife rolled her eyes in wifely censure, but I insisted.

The waiter nodded approvingly when I ordered it, normally a sign that I’m in for something unique, something that “only Japanese would order.” I knew that to be the case with the bone sake when the waiter set the glass down on the table. It was clearly bones in sake, not some poetic, metaphoric name alluding to something different. It was a complete fish of bones soaking in a glass of clear alcohol, like a preserved specimen from some dusty nineteenth century laboratory.

The waiter pulled off the wood top, flicked a lighter and set it aflame. The small booth filled with the smell of bones and burning alcohol. Then, he quickly set the wood top back on and left me and my wife and the bones and alcohol on our own.

The flame seemed to have crisped the top part of the bone and cartilage. A few hard, white bits floated to the surface as I swirled the warm glass. The aroma cut through all the other delicious smells of the place—raw fish, grilled meat, tempura, fried vegetables and fresh sake.

The taste was weakly sake and strongly fish bone, stronger than any bone I had ever had before. On top, the flavor was charcoal-ish, an organic burn. Below, the bone flavor came out fully. I had to breathe to take a second sip. Bone.

After that, I sipped hesitantly, wondering if the bone flavor would strengthen as it soaked. For the first time in a very long time, I felt I simply could not finish something.

I leaned back on the cushions in the comfy wood booth and peered around the izakaya to see if anyone else had ordered the same. The other customers were all enjoying nice, cold glasses of sake, iced shochu and big mugs of beer. In front of me floated a skull, upper and lower jaw, fins, ribs, spine, vertebra and cartilage. The very words were unappetizing, the syllables hard as bones.

Japanese food often seems to push the drinker and diner into a clear, direct encounter with nature’s bounty. Raw fish is that exactly—the real taste of fish without any cultural interference, the same taste you’d have if stranded on a boat in the ocean and forced to fish for yourself. Other preparation methods, the fermentation of shiokara (squid guts) or natto (soybeans), are cultural techniques that enhance and ripen the food to bring your taste buds closer to the pure, original taste.

I sat there not drinking, deciding what to order instead. My wife had already declined repeatedly, scowling. I increasingly felt like I should be—or maybe already was–dissecting the bones, studying them, and sketching them like a zoologist or Renaissance-era medical student.

I tried to sip a bit more, but it wasn’t like drinking exactly. The entire effect was something else altogether–a bone to bone connection, as if being punched or struck by a hard object.

The bone sake brought me closer to the essence of bone, a place I wasn’t sure I wanted to be. When you get to the bones, how much closer can you get to anything else? There’s nothing inside fish bones, no marrow, no blood cell production, it’s just bone.

The drink seemed to be sending me back to that moment when fish leapt up onto land, bringing their bones out of the salty water into the air. And back into myself. We are, after all, like fish bones at some point when we develop through the stages of evolution as fetuses in the womb. Was that the point, I wondered? But of course, there was no one to ask.

I felt a little disappointed with myself. I had always been proud of being open enough to eat every animal, insect, vegetable, fruit or concoction set in front of me over the years, but I had to admit defeat. The fish bones, so small, so frail and usually disposable, were more powerful than me. My curiosity, half-joking, half-macho, had met its match.

A couple of beers, some familiar yakitori comforting tofu set me back into a lighter mood, but I would think about my defeat for several days after, until the taste, the feel, the boniness, finally disappeared from where it had settled deep inside my body, where I had started to worry it would remain forever. It possibly always will. (March 25, 2017)

January 13, 2017

Tokyo Arrows

A long hallway at Heathrow airport once totally freaked me out. Jetlagged in from Tokyo, I followed the one sign directing me towards baggage check. After a few minutes, another hallway cut to the left. No advertising, no sign, just a hallway. Other jetlagged people stumbled forward, but I turned back with my mind in a muddle, immobilized.

I realized what I needed was an arrow. Living in Tokyo, I’ve become addicted to arrows. Over the years of commuting, I’ve grown dependent on arrows to guide, direct, protect and keep me moving in the right direction. In Tokyo, arrows stream pedestrians, both of which there are no shortage of, all the time, everywhere.

How many total arrows are plastered over station walls, signs, street corners and sidewalks in Tokyo? As many as there are directions, as many as there are people to follow them. The arrows rise constantly over the heads of pedestrians like thought bubbles of where to go.

You can tell how crowded an area can get by how many arrows there are. In stations like Shibuya and Shinjuku, arrows abound, flying overhead like the first attack in an old Japanese samurai movie. In some neighborhoods, the arrows are confined to discrete signs pointing the way to a clinic or local museum. But they are always there.

Fortunately! Without those arrows, Tokyo could not function. What would happen, I sometimes wonder, if all the arrows were removed? Everyone in Tokyo would head the wrong way—or worse—half of Tokyo would head the wrong way. The city would grind to a confused, irritated halt, like me in Heathrow.

[image error]Arrowless chaos would not be pretty. People would be searching overhead for guidance, stopping suddenly, backtracking, finger-searching cellphone maps, bumping into each other, barely missing bumping into each other–in short committing all the disruptions that never happen in a normal, arrow-laden Tokyo day.

No one looks good lost. Being lost in Tokyo is one of the few times stone-faced Tokyoites openly express exasperation and embarrassment. Their faces scrunch up and frown and redden and squint. It’s unpleasant to see. Though Tokyoites generally hurry past the lost and confused, the internal thought of stopping to help always pops up, slowing even the confidently directed.

It’s true I don’t like to be embarrassed should other people think I don’t know where I’m going. The arrows let me slip smoothly in to Tokyo’s pedestrian traffic and appear to know my way around better than I actually do. When going someplace new, I can glance arrow-ward and find where I’m headed. I’m spared the shame of misdirection.

Most times, though, following arrows is less choice than necessity. In peak crowds, to go against the arrows is to invite disaster. A crowd moving in the right direction can speed you along; but a crowd with even one person trying to buck the flow throws the entire crowd out of whack. To change direction, you have to flow downstream angling gently to the side until you can find a saving pillar, wall corner and opening to reverse course. Then, you look for the arrows back the other way.[image error]

Arrows proliferate when construction is going on, which is often. You can sense the irritation when temporary arrows prod people out of their ingrained routes. The short-term arrows are pasted on walls and pillars, apologetic for the inconvenience.

Over the years, I’ve resigned myself to trusting the arrows. Following one wrongly read arrow can put you a long way from where you want to be. Ignoring the arrows can spill you out the wrong exit out of a station with a twenty-minute walk to right yourself. Of course, you then need to follow the arrows back through the maze, sighting more carefully, paying closer attention.

Though I appreciate the smooth flow and admit the simple, obvious utility, at times I feel like I’m being ordered around, as if I’m filling in some pattern pre-written for me. I feel like I’ve been trained, like a Pavlovian dog for some trick, the trick of walking in a crowd. I’m crowd-trained.

Some days I feel like I’m led from arrow to arrow as if playing a board game. I feel like I’m moving towards the prize at the end, rewarded along the way by not smashing into people. Other days, the arrows feel like commands, relentless, inescapable, unavoidable. I like the arrows ordering other people around, just not ordering me around. But I always capitulate.

And there are more and more arrows all the time. It’s strange that the more cellphone navigation apps there are, the more arrows are put up. Are we more in need of being herded than ever? Is the proliferation because of the foreign tourist boom? Are people just more lost than ever?

I wonder if there’s some other symbolism underneath it all. The phallic shape, even when bent and curved, is undeniable.  Little triangle-rectangle shapes move the entire population of the city around. Could it be that easy? Are they symbols of power? Some kind of mind-body control? A message from the deep state? Or are the arrows a step forward in urban planning and civility? A thoughtful, helpful politeness in a refined city?

Little triangle-rectangle shapes move the entire population of the city around. Could it be that easy? Are they symbols of power? Some kind of mind-body control? A message from the deep state? Or are the arrows a step forward in urban planning and civility? A thoughtful, helpful politeness in a refined city?

All of those I guess. I feel the arrows keep everyone on track not just physically, but also psychologically. They are visual shouts of “ganbatte” (don’t give up, persevere). They float overhead encouraging and hopeful, a reassuring sign that there IS a direction and you are heading in it, your passage marked by each arrow, one after the next, left behind.

January 14, 2017

November 14, 2016

Best Indie Book Awards

September 2, 2016

Gold Award Reader’s Favorite Awards

Gold Award Reader’s Favorite Awards

.