Cliff McNish's Blog

November 21, 2020

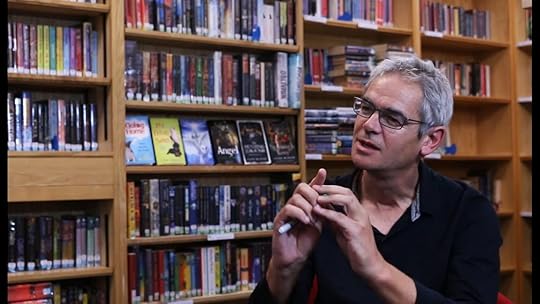

An Interview with Cliff McNish by Jacob Hope from CILIP

We are delighted to welcome Cliff McNish for a special interview to celebrate the 20th Anniversary of The Doomspell. A special limited edition hardback of the book together with an exciting new story The Light of Armath is available now. To find out more and read an extract from this, why not visit Cliff's website www.cliffmcnish.com

Please can you tell us a little about yourself?

I started off not being a reader at all. We had precious few books at home, and no children’s ones that I recall. I read comics until my English teacher in late junior school finally thrust C.S. Lewis’s Narnian tale The Magician’s Nephew at me. I often wonder if the fact that the first novel to grip me was middle-grade magical fantasy is the reason I automatically took up writing in that vein once I began. I suspect so. But oddly I never started writing until I was 38 years old, and even then only because I’d recklessly promised my nine year-old daughter a story about a witch – recklessly because I’d never written any fiction before, so I had no idea how if I could do it or not. That story, originally called Rachel and the Witch, finally became The Doomspell.

‘The Doomspell Trilogy’ is celebrating its 20th anniversary, congratulations. Can you introduce our readers to Rachel and Eric and the adventures they face.

Doomspell is slap-bang in the venerable tradition of wizards and witches, full of spells, counter spells and High Magic, with battles and stakes escalating as the children try to stop an immensely powerful Witch from getting what she wants.

Rachel is the main character, intensely magical; her brother Eric has entirely different and unique skills. But in many ways the Witch, Dragwena, is the character many children remember best. She’s very much the sizzling White Witch of Narnia with zesty added snake-bite. A Japanese reader once sent me a fan letter saying, “My favourite character is Dragwena. Not only do I look like Dragwena [she has four jaws and spiders that live inside her], but psychologically I am like her, too.” You can’t always think of something to reply when you get letters like that.

You’ve written a new story, ‘The Light of Armath,’ what parts of returning to the world felt easiest and most challenging?

In all honesty I thought I would struggle to be enthused writing about characters I’d created and left behind so long ago. In fact, the opposite occurred: the moment I started describing Dragwena in her eye-tower again, stroking her snake, irritated and restless, her entire character came back to me in all its full-blooded glorious villainy. I actually found I couldn’t wait to write about her again, as if she’d been sitting there expecting me to all this time, tapping a wand impatiently. Dragwena is the sort of relentless character it’s always a joy to work on. But in addition to her, I also wanted to do justice to a much-loved character from the original series, Morpeth. I felt I rather short-changed my readers by largely side-lining him in the in third book of The Doomspell Trilogy, and wanted to rectify that in The Light of Armath.

What can readers expect in ‘The Light of Armarth’?

First, I hope, an honest story. Readers who enjoyed this series have a lot of fondness for the memories, and it would have been horrible to sour that with a sub-standard tale. So I decided I wouldn’t inflict it on them unless I thought it was good enough (I’m talking about for Doomspell fans here, of course. The new novella could conceivably be read stand-alone without knowing the first Doomspell book, but I wouldn’t recommend it, several aspects will be deeply confusing.).

Second good point, I hope, is that it’s not a little dinky nothing of a short story. It’s a proper novella, so it has some significant development. The last thing I wanted to do was bring out a 20th Anniversary issue with a thin story, plopped in the book as an excuse to re-release it.

Third, I guess, is that the central spell in The Light of Armath is one Doomspell readers won’t have come across before, so that’s giving them something new as well.

Fourth, it answers a couple of questions left hanging around in the original book.

And fifth, I suppose, I’ve written it very much in the style of the original book as well, so if you like THE DOOMSPELL I’m guessing or supposing and hoping you’ll like this, too.

Oh and sixth – it’s in the original cover, and in a limited edition, for any collectors who may be interested in that.

Seventh – there is no seventh. (Which sounds like the starting idea for a new story, doesn’t it? ‘You may only perform six spells,’said the arch-mage. ‘Why?’ I asked. ‘Because the seventh spell unravels the world.’ ‘Ah,’ I said, immediately and secretly looking forward to that moment ...)

Voice feels a tremendous strength in your writing, how do you go about establishing this?

I don’t actually work on this consciously. What I try to do is create main characters that embody strong traits, and hook those characters into stories that seem worth telling. To some extent you, the author, describing things, are the key voice holding everything together, of course, but I think the real key is creating characters that want something desperately. If you do that, readers also start to passionately identify with or against them, and plots automatically head in interesting directions. I teach in schools a lot (usually invited by librarians!), and a couple of my main workshops focus on creating great characters and the steps needed to build a strong plot around them. If anyone would like my action worksheets on these worksheets simply ask, and I’ll send you them.

You’ve also written some highly successful Young Adult fiction including Breathe and Angel. How does your approach differ writing for Young Adults?

That’s an interesting question. And there really are some major differences. Language complexity and plot and character complexity, obviously, are greater in a teen novel – or should be! And romance is really not appropriate to mid-grade, though deep friendship is (even if you subvert that romance in teen stories, which I sometimes do).

The level of psychological tension you can sustain is also altogether greater in teen fiction, as well as the level of critical self-examination, guilt, motive-checking, angst etc. so if you want to explore those things you swim towards teen fiction.

Another massive difference is who your enemy tends to be. In mid-grade fiction the main opponents/antagonists tend to be external (eg Matilda by Roald Dahl, it’s not Matilda unable to come to terms with her crummy family, its Miss Trunchbull in all her magnificent excess), and it’s lovely to be able as a writer to focus on those external foes, keep the main children fundamentally good and supportive of each other and not constantly questioning their motivations. With teen fiction motives become murkier, the monster is often the one within, which of course is exactly what leads to opportunities for fully-rounded character development not usually so necessary in mid-grade.

Breathe has won numerous awards and selected as one of the UK Schools Library Network 100 best adult and children’s novels, what do you think makes it so popular?

I honestly don’t know. First, perhaps because there are simply not that many decent ghost novels for late juniors/early-mid teens out there, even now, so it fulfils a need (because who doesn’t like a good scary ghost story?)

But perhaps there are, if I can conjecture, a couple of other aspects: 1) the ghost mother at the centre of the plot is truly a lost soul who is utterly convinced she is acting out of love. That whole theme of love and death/love versus hatred in the novel has a resonance that seems to appeal equally to children, teens and adults. A lot of children’s ghost novels tend to skirt the surface of some of this meaty thematic stuff, but Breathe doesn’t. 2) Maybe my creation of the realm of the Nightmare Passage also has something to do with it, too. It’s a place in the novel readers tend to remember. The Nightmare Passage only occupies a small part of the novel, actually, but readers have often written to me about it or mentioned it.

Can you tell us a bit about the film script you created for this?

OMG don’t get me stated on this! First, I decided to learn to write a script with formal correctness using the standard software package, which is called Final Draft. I did that purely as an experiment to learn the medium, with a view to creating entirely new film and tv scripts. Then a major film production company based in L.A. contacted me, showing an interest in the rights for BREATHE. That led to me mentioning the script I’d written, them saying great, show us it, and then working and reworking it many times under their guidance. In the end I worked on endless drafts, but could never get them to settle on the story. It was incredibly frustrating, and put me off film scriptwriting almost for good! But I still have my final script, which I like – and it’s very different from the novel. It’s now an adult ghost story, where the central characters are two women, one alive, one dead, battling over possession of the same son. I think it has as much zest as the original children’s novel, but who can really know? It’s sitting, as they say, in my desk drawer. Like a lot of things you write, it might never get an audience. Maybe I’ll post it up for people to see one day ...

What can we expect next from you?

Writing The Light of Armath gave me a new lease of life where magical fantasy is concerned. I’d had a synopsis for a new mid-grade magical fantasy in my desk for years, basically untouched and unworked on while I concentrated on (mostly) teen age fiction projects, and also some adult horror. After finishing The Light of Armath I dusted the synopsis down, tested it on my daughter (she still reads my stuff!) and realised I liked it. Well, I’d always liked he central idea of a world (our world) with magic emerging in various extraordinary ways, but now I felt I could write it. That it would be fun to do, in other words. So I’m penning it. I guess I’ll have EARTHSPELL out to beta readers within the next six months. Either that or it’ll turn into total pap in front of me and get quietly shelved. Watch this space!

Read an extract from the new novella The Light of Armath at www.cliffmcnish.com

July 1, 2019

Book Competition

To celebrate the release of the new edition of 'The Hunting Ground' we're giving away 5 copies. To enter the draw, just email me the answer to this question:

Q. In my novel 'Breathe' what was the name of the Ghost Mother's daughter?

Send your answer to me using this link www.cliffmcnish.com/contact

I’ll then put all the names together and my own daughter will pick 5 winners out of a hat. All entries received by 8th July will be entered into the draw. Good luck!

Winners will be announced on 10th July on my website and Facebook.

‘The Hunting Ground’ – Cliff McNish in conversation with Marty Mulrooney from Alternative Magazine Online & Keith B Walters

The new paperback edition of ‘The Hunting Ground’ will be released on 1st July 2019.

MM: What can you tell us about your book?

CM: It’s about two teenage brothers who go to a new mansion house and discover a ghost there so terrifying that other ghosts have stayed behind just to contain it. In my first ghost novel, ‘Breathe’, I created what is sometimes known in the trade as a ‘good-bad’ character, the ghost mother. You can take your pick on where morally you think she deserves to end up.

In ‘The Hunting Ground’ the ghost is an undiluted menace. I’ve spent more than ten years creating villains, and though it’s fun to give them more rounded personalities, it’s sometimes good to do exactly the opposite – create a heart of unmitigated darkness.

MM: How much research is involved when you write your books? Glebe House in ‘The Hunting Ground’ almost feels like a real place!

CM: For my first ghost novel ‘Breathe’ I did quite a bit of research into certain aspects of burial etc – almost none of which actually got used. I didn’t do any research of real mansion houses for ‘The Hunting Ground’. I just pooled my knowledge of such places together, and then used a few specific details to make it feel real. Actually, there’s a trick of the trade here: you revisit a place, in a slightly different way, like the East Wing, and those nuanced differences in a by-now familiar setting (since you’ve read about it once) make it feel more real.

KBW: How did the doll being dragged across the floor and its head bouncing along come about? – That’s an image that still stays and haunts me now.

CM: I don’t know. The doll idea – well, every creepy ghost story has to have a little dead girl and her doll she still won’t be parted from, doesn’t it? But the bumping/dragging stuff … I just wanted something unnerving you would hear and not understand for a while… ghosts stories should always be filled with those sort of things, don’t you think? Less seen, more heard…

MM: When did you first start writing fiction?

CM: When I about 36/37. I wanted to be in closer contact with my 9 year-old daughter, from whom I was separated. She loved witches. I decided to write her a little story about one. It just got bigger and bigger – and I found, quite by chance, that I enjoyed creating monsters…

MM: You seem to have written most prominently within the fantasy and horror genres. What makes you lean towards these genres and which do you prefer the most?

CM: I love both equally. Fantasy with a dark horror edge sits very naturally with me. As for why I like these genres, who can say? All I know is that unless I include a powerful element of real fantasy in my work I often lose interest in it. And while some people would say that I am often writing ‘horror’ I don’t see it as simplistically as that. My imagination does incline me towards dumping my characters into deeper and deeper trouble, but I think there are good writerly, structural, plot-related reasons why this makes sense. On the other hand, I can’t deny that at some primal level heading for the dark side appeals to me. I’ve no idea why really. I guess I’d feel more comfortable turning the question around to other novelists, and asking why they prefer, often, not to do that? I mean, why bother writing about happy friendly ghosts when you can do the scary stuff?

MM: Do you believe in ghosts in real life?

CM: No, though I’m keeping an open mind. Hold on, what’s that dark thing moving just behind my curtain…?

KBW: Do you have a favourite ghost story in fiction?

CM: I don’t have one single favourite ghost story, although two I’ve read recently have impressed me for different reasons.

1. 'Strangers' by Taichi Yamada – an adult Japanese ghost story that is deceptively simply written and very beautiful and cold.

2. ‘My Brother’s Ghost’ by Allan Ahlbeg is as wistful and beautiful a ghost story for kids or adults you’ll ever read. The Guardian short-listed it many years ago.

MM: How long does it usually take you to write a book?

CM: Generally about 9 months, 3-4 months to do a first draft, then the rest to get all the revisions done and dusted. But my horror novel ‘Savannah Grey’ took 2 years. Its writing became a horror story! And there are other novels I’ve never got right.

MM: What inspires you as a writer and where do your ideas come from?

CM: My inspiration comes largely from other writers. When I see what they do – how they create these extraordinary edifices from nothing – I’m deeply awed and inspired to attempt in my own small way to emulate them. As for where my ideas come from, in the end we’re all saturated in the same cultural environments, books, TV, film, interpersonal relationships – and the ideas filter out of some kind of hash of those things in a piecemeal, impossible-to-fathom way.

MM: Your books are written specifically for young adults. Do you think older readers can enjoy them too?

CM: Actually, quite a lot of my readers are adults. I’m pleased about that, because I do include themes in my fiction which younger readers might not yet have the experience to fully appreciate. Someone once pointed out to me that there’s a strong theme of guilt running through my fiction. Guilt is not an emotion or mental state unique to adults, but adults have more experience of its forms than most younger people simply because they’ve been alive longer. You have seen more guilt; you have felt it yourself. That leads you into other regions: forgiveness, for example, and all its attributes.

KBW: What scares you?

CM: Real life scares me all the time. In fiction, I’m scared when an author makes me like a character and then does nasty things to them that are totally unexpected but feel psychologically true.

MM: Are there any other genres you would like to explore in the future?

CM: I’m quite happy for now working primarily within the horror/science fiction/fantasy genres or hybrids thereof. I have no ambition to move outside of them and write, say, a romance, or historical fiction. But I have written two novels that are more humorous about animals – GOING HOME and MY FRIEND TWIGS – so I’m not a totally black character. I suppose if I did move elsewhere it would be into pure thriller/crime writing. But I love creating monsters too much ever to stray for too long from fantasy writing of some kind.

KBW: What can we look forward to next from you?

CM: At the moment I’m writing another ghost novel for teens provisionally titled LILY’S MONSTER. Then I think I’m going back to my first love – fantasy. It’s also the 20th anniversary of my DOOMSPELL trilogy this year, so I’m going to write a new Doomspell short story. A prequel.

www.cliffmcnish.com/the-hunting-ground

www.alternativemagazineonline.co.uk

September 22, 2018

'Breathe: A Ghost Story' Reviewed by Ren Zelen

‘Mommie Dearest…’

Mother-love is a complex thing. Our relationship with our mother is the most fundamental and determining relationship most of us will ever have, whether we like it or not. It can be a force for good or… not. Its repercussions may be felt throughout life and sometimes, persist even after death.

In reality we don’t always find the ‘unconditional’ devotion and support that is the idealized version of motherhood. If we dig a little deeper into the mother-child dynamic we might discover the most complicated of motivations and desires – as different in each case as the individuals involved. In Susan Hill’s popular novel ‘The Woman in Black’ we saw the vindictiveness that could be unleashed when motherhood was denied. One might also wonder what the possible conclusion of an over-protective mother-child relationship might be? Cliff McNish takes a look at obsessive mother-love in his book ‘Breathe: A Ghost Story’, and explores its more chilling consequences.

After twelve-year-old Jack’s father dies suddenly, his mother Sarah moves them to an old farmhouse in the country. It’s an isolated, crumbling old place, and it has a history. Sarah hopes that by surrounding Jack with unfamiliar things he will be distracted and diverted, and this might help him recover from the shock of losing his beloved father and allow them to console each other and make a fresh start.

But Jack has a special gift. He is a medium with the ability to sense people through the memories imprinted on their possessions and objects. There are more than just memories in Jack’s new home; there are ghosts.

Initially, Jack loves the old house, even when he discovers that the woman who lived there before them died in the very bed in which he sleeps, he is not afraid. As he begins to sense the presence of other spirits he discovers that the house has been haunted for more than a hundred years by the ‘Ghost Mother’, who has forced the spirits of four children to join her. She tells Jack a sad tale of how she lost her own young daughter, Isabella, to Tuberculosis, and how this left her desolate, lonely and inconsolable. All the ghost wants is to be a mother again and to look after a child. Jack has asthma, and this makes him an ideal candidate for her tender care – she will be a mother to him, better than his own could ever be, “I never had a son, you know, though I often wished for one of my own”. She offers him only the deepest devotion and affection, but, if that is the case, why are the ghost children so terrified of her?

We find something disturbing about the ‘Ghost Mother’ from the outset. Her excessive ‘devotion’ to Jack and her sympathy for his physical vulnerability only serve to make us more uncomfortable. She displays unpredictable mood swings and violent passions when questioned – her neediness has something deeply selfish and avaricious about it. When Jack doesn’t respond to her the way she wants him to, the Ghost Mother changes her tune.

Frantic when thwarted, she scrabbles for a way to feed her need and takes her opportunity – she enters and possesses the unsuspecting body of Jack’s real mother, Sarah. An internal battle begins, but the Ghost Mother is strong. Where does she get her strength? The frail ghost children she keeps prisoner are the clue. It is soon evident that she is a menacing character -unbalanced and merciless in the pursuit of her own desires. She is malevolence itself in her treatment of the child ghosts – and ultimately, of the living boy and his mother that she now has in her power.

Cliff McNish’s ghost story is ostensibly one written for young adults, but you can take it from a mature and seasoned reader of the gothic and ghostly, that it has been a long while since I have come across an entity as frightening as McNish’s ‘Ghost Mother’, and longer still since I was genuinely scared for the characters of a book, flipping the pages frantically in order to see what becomes of them. The ‘Ghost Mother’ is a truly ominous creation and we pity those plagued by her rapacious spiritual and emotional vampirism. She is not even the ultimate threat, as the beleaguered ghost children desperately try to avoid her sending them to the dreaded ‘Nightmare Passage’-an evocatively imagined realm of pain, despair and suffering.

‘Breathe’ is a satisfyingly constructed, genuinely disturbing story of a misguided, pathological self-absorption. This is scary in itself, but here it has the added frisson of a psychotic ghostly presence. Believe me, it will give a whole new meaning to the expression, a ‘suffocating’ love.

Reviewed by Ren Zelen

http://manoflabook.com/wp/

January 17, 2018

Alex from 'Millennium Riot Readers' asks the questions

Alex: Do you have a preferred writing style?

Cliff: No. The voice tends to choose itself. I don't consciously experiment with style, but I guess the multiple first-person perspective I use in the Silver Sequence is fairly unusual for younger fiction and I'm sometimes described as a "bizarre" stylist where my pure fantasies are concerned, but that's mainly because my creations are fairly non-standard fare and because I do like to write first-person perspective from the villains' viewpoint. That's always a joy. The overall truth is that I just find a voice that works for each kind of story I'm writing and, once I'm comfortable, just go with it. If people read Going Home and can't recognise that person as the one who wrote Silver World – well, that's terrific. Form/content over style wins.

Alex: How important are your characters to you as you are writing?

Cliff: Very. In some novels like 'Breathe' – which almost never leaves a house – and 'Going Home' – which never leaves the dogs' home – you'd better get your characters right because you have no interesting locations to distract the reader from underdeveloped protagonists.

Alex: Are there any characters in your books which you particularly relate to?

Cliff: The torn Nyktomorph in 'Savannah Grey'. Mestraal and Hestron in 'Angel'. Walter in 'The Silver Sequence'. I can't even begin to tell you why. They just felt the most human – though only one of those is actually human at all. In lots of ways I like to do that – explore what it means to be human. And monsters, or archetypal angels, are perfect mirrors for that.

Alex: What sparked the initial idea for 'Angel'?

Cliff: A saw a little girl lying in bed, with light gradually increasing on her sleeping face. When she wakes she sees a beautiful angel. But here's the part that made me write it – the angel starts crying in front of her. An adult weeping at the bed of a child. I didn't know why. I sort of wanted to find out.

Alex: Your YA novels are always so different from each other, with 'Angel' being more of a "chick lit", 'Breathe' being such a chilling ghost story and 'The Hunting Ground' more of a horror. Do you think it's important to keep upping your game and differentiating between styles of writing and genres?

Cliff: Angel as chick lit? Really?! To me it's more a kind of moral fable. I don't consciously do "different" books. I just wait for a story idea to grab me from amongst the many that flit in and out of my head. At the moment those are mostly humorous, warm storylines. They used to be darker. I honestly can't chart why, but I like both strands. I just wait for a gut emotional reaction – a wrench that says, "Yes, this is worth writing."

Alex: Where do you draw your ideas from? Personal experiences, everyday experiences or a mix or things?

Cliff: Hardly anything from personal experience until I wrote ‘Going Home’ which is definitely informed by my days fostering dogs. I genuinely have no idea where most of my ideas come from.

Alex: When beginning a new novel do you plan the characters first and then fit the story around them or do you plan the whole thing out methodically?

Cliff: I tend to have the idea first – and instantly embedded in that are usually one or two main characters who will carry it. I then play with the idea – see if it has 'legs' as they say. If I'm still excited, I start to develop the characters to carry the idea, and sketch an outline plot. If that still looks good, I'll sketch certain scenes in more detail and start thinking about character motivations – and so on, ad infinitum. The entire cast/plot develops in a higgledy-piggledy, meandering, blind-alley-galore riot of confusion and feedback loops from that point. There's nothing linear or consistent about it. I just use what feels right and works – and discard all the rest.

November 23, 2017

The devil is in the detail: Writing Villains

Enemies, opponents, antagonists, villains. Whatever you like to call them, we love to hate them! Try to imagine your favourite books or films without the evil guys. How about Harry Potter without Voldemort or Draco Malfoy?

Or Lord of the Rings without Sauron and the orcs? Where would Twilight be without the James Coven? Or the Baudelaire children without Count Olaf?

Readers adore enemies in stories because it’s a secret pleasure to explore the darker side of our imaginations. But the reason we DEMAND them is because the nasty things they do to our heroes and heroines help us to love them so much more.

A good villain makes you sympathise with the hero so completely that the reader becomes desperate for them to succeed. Below are 18 top tips on creating great enemies in your own stories.

Tip 1 - Make your villain cause pain and suffering to characters we either like or who are innocent or defenceless.

This is the easiest and most effective way to make your reader hate a character. The more sadistic/merciless they are, the more we despise them. Voldemort attacks the defenceless Harry Potter when he’s just a tiny baby, instantly achieving villain status. Darth Vader destroys an ENTIRE PLANET.

As world-leading novelist Stephen King says: ‘To create a great opponent, make them hunger for other people’s suffering. That way they become the embodiment of pure evil.’

Tip 2 – Make them strongly want something the reader will hate them for.

In the Lion King, Scar wants to be head of the Pride. In Stormbreaker Herod Sayle can’t wait to kill as many school children in England as possible. In Lord of the Rings Sauron wants to enslave the world. We automatically detest him for it.

Tip 3 - Give the enemy control over your hero’s life.

Miss Trunchbull in Matilda locks kids away in the vicious ‘chokey’. Put your own villain in charge where no one can stop them.

Tip 4 - Make them appear more powerful than your hero.

Harry Potter is just a school boy wizard, but Voldemort is a master of the dark arts. The reader becomes consumed with fear for the hero.

Tip 5 – Ensure they break promises.

In Stormbreaker, Nadia Vole pretends she’s going to free Alex – then dumps him into a tank with a giant jellyfish. ‘When a character breaks a promise or betrays a trust, the audience takes that betrayal personally,’ says Orson Scott Card, award winning SF writer. ‘The villain has achieved true villain status, and readers will be longing for their downfall.’

Tip 6 - Make them a coward.

Malfoy’s always hiding behind Crabbe and Goyle or the influence of his family name. A hero never does that.

Tip 7 - Make them stuck up and condescending towards others.

We hate characters who think they are superior to us, people who sneer or treat powerful, influential, rich people better than the poor and powerless.

Tip 8 - Make them boast.

A hero remains modest. When things go right for villains they take all the credit whether they deserve it or not.

Tip 9 - Keep them humourless.

A heroine retains a sense of humour. When things go wrong for opponents, have them whine. Or, if they do joke, always make it at someone else’s expense.

Tip 10 - Have them blame everyone but themselves.

When things go wrong, villains always accuse and criticize others. Ensure yours do the same.

Tip 11 – Emphasise their vanity.

We automatically dislike anyone who brags about their looks, strength, deeds or the amount of money they have. Think of Moriarty.

Tip 12 - Make them cheats and liars.

Heroes are honest. Villains can’t be trusted.

Tip 13 - Give them no regard for other people’s feelings.

A hero is self-sacrificing and considers other people. Villains don’t care what happens to anyone else. They only help themselves. Think of the contempt the James clan in Twilight have for all humans.

Tip 14 - Make them petty instead of noble.

When Harry meets Ron on the train to Hogwarts he shares his food with him – he’s generous and warm-hearted. But what does Malfoy do? Cracks jokes about Ron’s poverty and talks about his ‘useless’ family. We despise him for it.

Tip 15 - Make them ugly OR exceptionally handsome.

We tend to distrust both. Think of the lovely but cruel step-mother in Snow White. Or Gaston in Beauty and the Beast.

Tip 16 - Villains rarely doubt themselves.

In Twilight hero Edward is constantly worried that he cannot trust himself with Bella. That makes him more human. In Hercules, Hades is only looking out for Number One. Himself. Villains just pursue their own interests and don’t question themselves or care who they step on.

Tip 17 - Build up the suspense by not revealing the villain too soon.

Sauron in Lord of the Rings is just a vast eye – and all the more alarming because we never really know what he looks or sounds like. To create real fear, keep you reader guessing for as long as possible. In Toy Story 3, cuddly Lotso Huggin Bear turns out to be a megalomaniac.

Tip 18 – Have people talk about your enemy fearfully.

The importance of this final tip is often neglected, but not by great storytellers. Characters are so afraid of Voldemort that they won’t even say his name. Sauron hardly appears in Lord of the Rings, but when you read the novel you always feel his presence. The reason is that even tough warriors like Aragorn never stop talking about him apprehensively. When great and brave characters like Aragorn and Gandalf regard Sauron as immensely dangerous, readers automatically get nervous. Have your own strongest characters do the same. Use them to stoke up the fear of your enemy. It works beautifully.

November 10, 2017

Working in Wonderland

Cliff McNish talks to Anita Loughrey about the differences between writing for children and writing for adults.

In some way children's and Young Adult books are all about first experiences - first day at school, first pet, first test of conscience, first love. They're all about becoming something, maturing; and mostly the children win through, they blossom.

Whereas adult stories are primarily about withstanding life. They're about enduring what life throws at us, about coping, and we tend to like those stories that show adults doing so with dignity and a certain steadfastness, which means the action and emotions are very different.

Romantically, for example, it's no longer usually about that first kiss and rush of hormones. It's about the loss of that love, or finding second love, which is harder, and adult characters are often not blossoming but surviving.

My favourite thing about writing for children is the return to innocence. A way back to that purity you had as a child, when all your experiences are so vivid, you are so open to them, and exuberance hasn't yet been tempered by grim age and a certain world-weariness. I'm trying to create my own Wonderland all the time.

Adult readers, as well as writers, are trying to find their way back to their own Wonderlands. You only have to look at a synopsis of the average adult novel to realise a stark truth: that we still love to read about child-like characters. By which I mean those characters who are not too bowed down by life's worries, they are finding that innocence and bravery and purity of purpose they had as children all over again.

A Wonderland, by the way, isn't 'what you think a child aged 10-15 would find interesting nowadays in a story'. It's what you find exciting now as an adult. Don't self-edit. Just come up with a creation that excites you. If you want to write a children's book, it will find its own way to become that.

Populate it exclusively with things you want in it. That way you'll be passionate about it. And please, please, try to be as original as you can. If you create a goblin, it needs to be different to any other goblin to stand a chance.

Try always to come up with your own vision. In my ghost novel Breathe, I created the Nightmare Passage, an endless plain of wind that drags the souls of children along forever. It's the most original part of the book and the part people almost always remember most, though it only features in about 20 pages of the entire novel.

At the moment, I'm writing a new novel aimed at teens, and I've also been dabbling on and off with both adult horror writing and children's picture books. It's amazing to go between the two. A lovely heart-warming story for children, with minor twists, can become devastatingly scary. The actual 'writing' for children is not even slightly different from the 'writing' for adults. People often point out what are seen as the 'obvious' differences: vocabulary, level of complexity and a nagging need to write a 'happy' ending for kids, to 'give them hope'.

If you really believe these shibboleths, I'd like to challenge you. Yes, to vocabulary with younger children, obviously, but there is almost no difference between top end YA and adult fiction as far as plot or language are concerned.

The proof of that is the fact that Frances Hardinge won the adult British Fantasy A ward for her so-called YA novel Cuckoo Song, and a few years ago Margo Lanagan' s Tender Morsels, originally marketed as YA, won the World Fantasy Award.

Actually, I would argue that the plot of the best novels aimed at eight year olds upwards, like JK Rowling's Horrible Potties series (only joking, Jo!), often have as many plot complexities and twists as your average adult fantasy novel. Kids can handle all sorts of narrative trickery.

And as for happy endings ... the truth is (shush) that the majority of adults like happy, closed endings to stories about as much as kids. It's true, it's true.

And who are the readers out there able to handle dark stuff? The adults? Sure. Some. But a lot of middle-aged adults I know really don't read that sort of thing any more. They prefer safer writerly climbs. Newsnight is bad enough (for me anyway; I hide behind the sofa). It's kids - especially teens - who love to immerse themselves in the darker side and, trust me, they can take any kind of ending you give them as long as its well-crafted.

A great children's book makes me - an adult - want to read it over and over again. Alexis Deacon's Beegu is a picture book that is a perfect mixture of tenderness, warmth, humour and a positive message about the love children offer.

Alan Garner's The Weirdstone of Brisingamen is a perfect way to turn the ordinary world into a dangerous fantasy one, while Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game is a book I come back to time and time again, because the author manages to create the ultimate true boy hero, someone you admire from the depths of your soul.

Who doesn't want to create characters like that? ls that latter SF novel for teens or adults? It's truly for both. All the great children's books are for everyone.

I've often reread Ender's Game when I want to be reminded what delivers characters we love. I'd recommend you do the same: take your very favourite books and analyse in detail what the author does to make you so impressed. lt will teach you far more than any standard guide.

So, if you want to write for children, there's nothing you shouldn't do. Finish a piece of work, put your heart into it, write without self-editing, and only then get the opinions of others. As soon as you self-edit you end up losing your nerve and writing, at best, the commonplace. Anyone can write that.

Be brave, throw it out to the world. Then cringingly edit if you have to. (And I've been there many times!)

www.cliffmcnish.com

www.anitaloughrey.com

www.writers-forum.com

October 21, 2017

Deepening Character: a conversation with Cliff McNish by Candy Gourlay

Whenever I meet up with YA author Cliff McNish to talk about craft, he always comes up with amazing wisdom about deepening character. A while ago, my favourite Cliff novel Breathe: A Ghost Story was listed on the Librarian's Top 100 adult and children's books (alongside Daphne De Maurier, AA Milne, CS Lewis and yes, Neil Gaiman). I thought this was as good a time as any to draw Cliff out of his technology averse shell (If I sound a bit stroppy, I am - the man doesn't know how to sell himself) ... and FORCE him to share his wisdom on deepening character.If you haven't read his books, they're dark, twisted and sometimes creepy - unlike their charming and not at all creepy creator.

Candy: Hi Cliff! I was chuffed to see Breathe on the librarians' Top 100 Books list! I loved that book and always thought it deserved far more notice than it got. How did you feel when you saw it there?

Cliff: I was a bit shocked and happily surprised. Breathe came out in 2006, which is already quite some time ago. Nice it's still recalled fondly and to be above Winnie the Pooh. Alphabetically above, but hey ...

Candy: You began your writing career with high fantasy with the Doomspell Trilogy then the Silver Sequence. By contrast to the vast worlds, Breathe is rather more intimate, a ghost story. Was it a turning point in your writing journey?

Cliff: The truth is that Breathe did not feel like a turning point at the time, merely a continuation of fantastical elements on a smaller scale.

But of course it is a chamber piece, not the galaxy, or the whole world changing this time, but a house, and only its four walls to hide inside. In the first draft that led to a lot of repetition; my learning curve as a writer, if I achieved anything, was to adapt to vary the novel by employing story shifts and character depths rather than relying on the set pieces and colour palette I had for the Doomspell Trilogy and Silver sequence. I wanted physical constraint, but I had to handle character more adroitly to keep the story flowing.

Candy: Whenever we meet to talk shop you often talk about taking every opportunity to deepen character. What do you mean by deepening character and how would someone know when it's been achieved?

Cliff: By character deepening I mean anything that helps us to identify more deeply and personally with a character in a story- anything that brings them away from cliche, into real life, and helps to differentiate them from other characters and make us really identify with them.

We tend to do that when they show classic values: courage under pressure, humour when the situation is dark, taking responsibility when it is easier to back out. When they behave, in other words, the way we expect adults to when they are given real choices.

Candy: There are some who would argue that younger fiction does not require such attention to character. What would you say to that?

Cliff: Children's stories need characters that show deep characteristics just as much as adults' books. So when I look at my own and other writers' manuscripts I'm always asking how I make those choice moments as powerful as I can. It's easy to miss opportunities - and deepening a character normally has a much bigger payoff than a plot twist.

Candy: How about a list of tips ...

Cliff: Okay, here are some hints and tips on deepening of characters we really want our readers to love.

1. Heap huge problems on them right from the start.

When we first meet Harry Potter, J.K.Rowling has already dumped a whole world of problems on him: his parents are dead, he lives on hand-me-downs, the Dursleys are nasty to him, he has a disfiguring scar – oh, and Lord Voldemort, the darkest and most powerful wizard in the world, is trying to kill him! Always, always, get sympathy for your hero/heroine by giving them really big problems to deal with from the outset. The bigger the problems, the better. Plunge them into terrible trouble. If you do that the reader will start desperately wanting them to get out of that trouble as well.

2. Keep building up the pressure!

In Stormbreaker, Alex Rider starts off by losing his last living relative and almost being killed in a car dumpster yard. But Anthony Horowitz skilfully builds the pressure from that point. He throws at Alex garrotting bikers, poisonous jellyfish and professional killers. By the end of the novel the combined forces of Herod Sayle enterprises are all trying to destroy him. Even if you’re writing comedy, never relent the pressure for long. Ideally each pressure event in your story should be bigger than the last as well, until at the end your hero/heroine is alone, facing the worst possible pressure, against enemies that have never looked more powerful.

3. Give them a noble desire.

All great heroines and heroes at some point give up something they want personally for the greater good. In Twilight Edward dearly wants to taste Bella’s blood. Instead he chooses to deny himself and protect her with his own life.

In the final battle scene of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone Voldemort offers to bring Harry Potter’s parents back if he’ll join him. When Harry (already half dead at this point) says no, sacrificing his most personal desire, and instead stands and fights because it is the right thing to do, he achieves true hero status.

4. Provide at least one very powerful enemy to confront.

Where would Roald Dahl’s Matilda be without Miss Trunchbull?

Or Bella and Edward without the James Clan? Great villains help us to identify much more strongly with heroes.

5. Give them a sense of humour.

We’re prepared to forgive even villains a great deal if they make us laugh. It works doubly so for our heroes. Keep them seeing the amusing side no matter what happens. Plus, when they can still smile under pressure, it shows their inner strength.

6. Make them doubt themselves.

Real heroes and heroines aren’t sure they can cope. Their self-doubt makes them more human, more believable. It also makes it harder for them to overcome their problems, so the triumph when they do so is even greater. In Twilight Edward doubts he can restrain himself from drinking Bella’s blood. In The Story of Tracy Beaker Tracy can’t even admit to herself that she’s struggling. She cries all the time, but pretends the cause is just hay fever.

The greatest heroes are very human indeed – and that’s why we love it when they succeed.

7. Give them a dark side.

Harry Potter speaks parceltongue, linking him to Voldemort.

In Twilight, Edward is a real vampire with an intense desire to drink human blood. Tracy Beaker has so many behavioural problems that she’s constantly messing up her chances of happiness. We love our heroes to be struggling with powerful issues of their own – when they are their own worst enemies!

8. Have them help the defenceless and the weak.

Real heroes constantly place themselves in danger to help others. In The Hunger Games Katniss Everdeen volunteers to enter the games to save her little sister.

In Lord of the Rings every single member of the Fellowship repeatedly puts his own life in danger to protect Frodo, the ringbearer.

9. Make them brave enough to overcome their worst fear.

We love characters who are physically brave. But far more important than that is that at some point your hero or heroine has to be brave enough to confront their worst fear and overcome it. Tracy Beaker’s greatest fear is that her mum will never come back for her at the children’s home. In the end she accepts that her mum doesn’t care enough about her to ever return.

It’s amazingly brave of Tracy to admit that to herself. After waiting so long, it’s the bravest possible thing she could possibly do. What’s your hero/heroine’s worst fear? What’s the hardest thing for them to do?

10. Keep them modest.

Sam Gamgee in Lord of the Rings just wants to go back home to Hobbiton and lead the quiet life of a gardener.

He never boasts, just quietly does the right thing. Keep your hero humble. As part of this, make sure they always have a deep regard for other people’s feelings, especially those people who are usually ignored. We love this in a character.

11. Give them a talent.

Harry Potter is superb at using magic, especially the dark arts. In The Hunger Games Katniss Everdeen’s gifts for foraging and hunting are what keep her alive.

Even apparently normal Bella in Twilight discovers she has the unique talent of being able to prevent vampires using their powers. We truly love our heroes/heroines to be unusually good at something.

12. Ensure they grow as characters.

By daring to confront Voldemort, Harry Potter becomes much stronger than the schoolboy who was scared to confront the Dursleys at the beginning of book 1. By the end of The Secret Garden Mary Leonard has brought happiness back to a family and is no longer the selfish, spiteful girl she was at the start. By confronting their worst fears and their enemies they’ve become someone we can deeply admire, someone the reader wants to be themselves. If you do the same with the characters in your own stories readers will love you for it.

Candy: Well ... that's an amazing list. No excuses for cardboard characters now, everyone.

October 20, 2017

My top 10 most frightening books for teenagers

It's a curious thing that most people's reading tastes become progressively less dark as they age. While I see many of my middle-aged friends settling down to read nothing more scary than Pride and Prejudice if you please, a sizable proportion of their 9-12 year-old children are actively ignoring them to seek out fiction that is edgy, scary and, frankly, mayhem-led.

Teenagers are the real trench-terrorists, though. They gather like happy ghouls at the shelves of dark fantasy, horror and real-life crime or its facsimiles. Some won't read anything else. It's only much later they'll realise they did so because at least for a few years they were embarked on the biggest and most exciting search for personal identity the majority will ever undertake in their lives. During that time exploring the darker, more frightening seam of the psyche is not just a secret pleasure but a necessity.

But what do we mean when we say a book is frightening? A younger reader might mention a body count, and certainly a blood count. But we soon demand more interesting shivers than that, don't we? And in some of them you're not even safe when you're dead. Probably the greatest science fiction writer of all time, the American Philip K Dick, was once asked by a fan at a convention what he thought life after death might be like. He replied: 'How do you know you're not already dead?' An interesting enough answer, but the really frightening question is the obvious follow-up: if you are dead – and so this is the afterlife – do you regard it as hell or heaven?

Here's a scary little story for you: 'The last man on Earth sat in his living room. There was a knock at the door.' While you think about that, here's my choice of ten stories that in different ways will frighten and enthral even the most unshakeably cocky teenager.

1. 1984 by George Orwell

1. 1984 by George OrwellI'm so glad this was on the national curriculum when I was at school because it forced me to read it. It is only now, though, that I understand why the novel is so chilling. It's because when the rat-cage is lowered over poor benighted Winston Smith's head, and he cries out, 'Do it to Julia, Do it to Julia!' he is renouncing love, and nothing can have meaning after that.

Tim is universally recognised as one of our finest authors of teenage fiction, but one of the least well-known slices of his work is this short, breathlessly-intense first novel. Midget doesn't have much going for him. He's fifteen years old, three foot tall and trapped in a useless, twitching body he can't control. To add to his woes he's tortured by Seb, his cruel older brother. We're set for a roller-coaster ride of psychological darkness, and Bowler delivers it in bruising incandescent waves.

3. The Tulip Touch by Anne Fine

3. The Tulip Touch by Anne Fine

Nobody wants teenager Tulip Pierce in their gang. She's a truant, taunts the teachers and tells strange and terrible lies. None of this matters to our narrator, Natalie, however. She finds Tulip exciting, and at first doesn't mind playing her bizarre games ... until Tulip goes too far. Sometimes horror is best doled out in gruesome, excessive proportions, but here Anne Fine generates an electrifying level of fear with the quietest of hints. There's a line about flaying and freckles I've never forgotten.

What would it be like to have buttons instead of eyes? Coraline moves to a new house. It seems identical to her own. It even has an identical mother, her Other Mother, who likes to carry a sewing needle and thread. And when she looks into Coraline's eyes her new mummy has a suggestion to make ... This little novel is as sleek and original a nugget of fear as you'll find.

5. The Long Walk by Stephen King

5. The Long Walk by Stephen King

King is the best-known horror writer in the world. What are much less well-known than his blockbuster novels are the shorter books he wrote under the pseudonym Richard Bachman. The Long Walk is the best of these and in my opinion the most moving single novel he's ever written. In a near-future world a group of teenage boys are walking across America. Their prize is untold riches and celebrity. But only the last one left walking wins. The rest, as they falter, are shot like dogs. This novel is a great slice of real horror. And by that, first and foremost, I mean characters you really care about - because if you didn't what does it matter what happens to them? But I also mean the set-up is perfect. Horror is all about uncertainty. In The Long Walk nothing is certain except death, there is nothing you can take comfort from, and the only rules you can understand are ones controlled by your enemy.

Dan Abnett is probably the best writer of dark military SF in the world. Set in the distant future, this volume in the Horus Heresy Warhammer 40,000 series is about genetically-enhanced men fighting frequently inglorious wars for dubious reasons. What lifts the series into true pathos and makes the story so frightening is the dark heart of the series' premise. You think you're going to be reading about gladiatorial contests in some far-flung future, and Abnett delivers on that in spades for you action-fans, but what you get on top of that is a tragedy which ultimately assumes Shakespearean proportions.

7. Looking for JJ by Ann Cassidy

7. Looking for JJ by Ann Cassidy

What should happen to 17 year-old Alice Tully after she murders her friend? Is there any way that she can lead a normal life? Does she even deserve to? This devastating story of betrayal and death-on-the-river rightly won The Guardian fiction prize in 2005.

I remember a friend handing me this book in 1997. It was a hardback, had been around for years and the author, a Welsh educational psychologist working primarily with dysfunctional children in the U.S.A., was virtually unknown. Since then she's become a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic with her true stories of youngsters facing terrifying real-life problems. Ghost Girl may the best. It features little Jadie, who never speaks, laughs or cries, instead spending every waking hour locked in her own private world of shadows. She's almost a ghost. And when you finally discover the truth about why it is mind-numbingly terrifying. Ghost Girl lets you off with an ending that makes you want to read Torey's next tale, but on the way you'll frequently find yourself putting the book down ... and picking it up again.

9. Bloodtide by Melvin Burgess

9. Bloodtide by Melvin Burgess

I've left my favourite scary stories of all time to last. Bloodtide is an urban fantasy set in a near-future where rival gang lords vie for power in a London watched over by capricious Norse gods. It's a retelling of the ancient Volsunga Saga, but carried off with such power, originality and vision that it is quite simply one of the most eloquently dark books ever written for a young adult audience. When the novel came out in 2000 critic Wendy Cooling said that 'it will leave teen readers with shredded emotions that will last forever.' That's a perfectly accurate description of this book. Dystopian fictions abounds these days in the YA field, but Bloodtide ranks in its savage brilliance alongside any of the adult twentieth-century classics. You need a strong stomach, but if you can handle it this is not a book you'll ever forget.

10. The Diary of Anne Frank by Anne Frank

10. The Diary of Anne Frank by Anne Frank

This has to be the ultimate choice for me. It's terrifying partly because it's a true story about a girl's family trying to stay alive in Nazi Europe, of course. The facts alone are terrifying. But that's not the only reason I've chosen it, or even the main one. Tragic millions appallingly lost their lives in concentration camps but it is always Anne we seem to go back to. And the reason is simply that she was a life-force. She was such a torrent of beauty and truth. The most terrible crime in the world is to take something wonderful and wilfully destroy it, and that's what happens. Re-reading Anne's diary extracts as an adult is an even more devastating experience than as a teenager, and I think I know why. It's because as you get a little older you become a bit more savvy about assessing human nature. By the time you get to 40, you've met enough other people to know just what an extraordinary vivid girl the teenage Anne Frank was. She's so full of life that as you reach the final few entries of her diary you slow down, as if you can somehow miraculously keep her alive just by not reading those last paragraphs.

The very greatest dark stories are all about love – about the absence of it, the removal of it, the denial of it, and the attempt of the human spirit to claw it back in any way it can. Anne's diary is full of love. Has anything more frightening or poignant, and ultimately life-affirming, ever been written?