Ralph E. Vaughan's Blog, page 3

September 11, 2019

Elder Egypt, Again

Back in the early 90s, when everyone was discovering the internet in a big way and everyone who was no one (and a few who were someone) was setting up a website -- "Hey, Ma! Look! I got my own place on the Information Superhighway!" -- I also set up a website. It was dedicated to Ancient Egypt, a long-time interest of mine. Once a month, I would post a well-researched, thoroughly illustrated article about some aspect of Egypt. The real purpose of the site, however, was to help students with their Egypt-related school projects. I received several emails per day, from elementary schoolers to university students. I didn't do their homework for them, but I pointed them in the right direction and gave them the tools to do their projects. And I answered a lot of questions, usually based on some misconception derived from a film (i.e., the reboot of The Mummy).

"No, sorry, Nigel, but scarabs are slow moving dung beetles,

"No, sorry, Nigel, but scarabs are slow moving dung beetles,

not cheetah-swift piranha-like insects that can strip the flesh

from some hapless explorer in 3.7 seconds. It's called 'special effects'."

About the same time, I fell into one of those "virtual communities" that were popping up all over the internet at the time. It was, of course, based on Ancient Egypt and everyone pretended they lived upon the shores of an electronic Nile. Not really being a big role-player, I gravitated toward the community newsletter, The Papyrus, and contributed articles. It was all lots of fun, but like the real Ancient Egypt, it all eventually subsided into the sands of time...the community, the newsletter, and, finally, my homework helper website.

Now, not quite thirty years later, I've dusted off and revised the old articles, penned quite a few more and resurrected them in a new venue as Enigmas of Elder Egypt. Here's a sample:

Click here to buy from Amazon

Click here to buy from Amazon

Click here to buy from anywhere else

Click here to buy from anywhere else

"No, sorry, Nigel, but scarabs are slow moving dung beetles,

"No, sorry, Nigel, but scarabs are slow moving dung beetles,not cheetah-swift piranha-like insects that can strip the flesh

from some hapless explorer in 3.7 seconds. It's called 'special effects'."

About the same time, I fell into one of those "virtual communities" that were popping up all over the internet at the time. It was, of course, based on Ancient Egypt and everyone pretended they lived upon the shores of an electronic Nile. Not really being a big role-player, I gravitated toward the community newsletter, The Papyrus, and contributed articles. It was all lots of fun, but like the real Ancient Egypt, it all eventually subsided into the sands of time...the community, the newsletter, and, finally, my homework helper website.

Now, not quite thirty years later, I've dusted off and revised the old articles, penned quite a few more and resurrected them in a new venue as Enigmas of Elder Egypt. Here's a sample:

Click here to buy from Amazon

Click here to buy from Amazon Click here to buy from anywhere else

Click here to buy from anywhere else

Published on September 11, 2019 09:37

September 7, 2019

The Gods Hate Kansas?

A large portion of my wasted youth was spent eroding my brain by watching cheesy old films. Well, some things don't change, so a few days ago I was looking for something to further erode my brain on Amazon Fire Streaming, when I came across a film called They Came from Beyond Space, a 1967 flick from Amicus Productions, a company I mostly knew from some very good Edgar Rice Burroughs adaptations and two really, really bad Doctor Who TV movies.

I thought, well, it could be an undiscovered gem or it might be dreck. Either way, it's 85 minutes. And I thought it would at least be passable, it being a British film. Yes, I know...I saw Devil Girl from Mars, but at least everyone had a British accent, and that automatically makes everything classier, such as when a developer names a housing development Robin Hood Estates rather than Pleasant Acres. But, then I recalled The Crawling Eye and how Tempean Films imported American actor Forrest Tucker (F Troop) to play the lead or how Hammer Films brought in Brian Donlevy to play the quintessential British scientist Professor Bernard Quatermass in the 1955 theatrical version of The Quatermass Experiment. So I gave in and took a sneak peek at IMDB: the lead actor is American Robert Hutton, but at least almost everyone will have a British accent. And it will still be 85 minutes. And I still had nothing else to do at the moment. So I queued the film and pressed start.

I thought, well, it could be an undiscovered gem or it might be dreck. Either way, it's 85 minutes. And I thought it would at least be passable, it being a British film. Yes, I know...I saw Devil Girl from Mars, but at least everyone had a British accent, and that automatically makes everything classier, such as when a developer names a housing development Robin Hood Estates rather than Pleasant Acres. But, then I recalled The Crawling Eye and how Tempean Films imported American actor Forrest Tucker (F Troop) to play the lead or how Hammer Films brought in Brian Donlevy to play the quintessential British scientist Professor Bernard Quatermass in the 1955 theatrical version of The Quatermass Experiment. So I gave in and took a sneak peek at IMDB: the lead actor is American Robert Hutton, but at least almost everyone will have a British accent. And it will still be 85 minutes. And I still had nothing else to do at the moment. So I queued the film and pressed start.

From almost the beginning of the film, I got a sense of deja vu, but when you have seen as many films as I have (I bought the book Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, and it was like reading the story of my youth) it's a common feeling. About the time they mentioned meteorites falling in a field and Hutton's character having a metal plate in his head, I thought: The Gods Hate Kansas, in which meteorites fall in a Kansas field and a character has a metal plate in his head preventing him from being taken over by alien intelligences hidden inside the meteorites. I also thought of "Corpus Earthling," an episode of The Outer Limits (original), but since that was about a scientist with a metal plate in his head that allowed him to listen to rocks plotting world domination, that was a totally different thing altogether. Well, mostly different. Well, at least the meteorites in They Came from Beyond Space and The Gods Hate Kansas didn't talk. A quick look trip back to IMDB confirmed my suspicion, that the film was indeed based on a book I didn't think anyone else besides me had ever read.

From almost the beginning of the film, I got a sense of deja vu, but when you have seen as many films as I have (I bought the book Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, and it was like reading the story of my youth) it's a common feeling. About the time they mentioned meteorites falling in a field and Hutton's character having a metal plate in his head, I thought: The Gods Hate Kansas, in which meteorites fall in a Kansas field and a character has a metal plate in his head preventing him from being taken over by alien intelligences hidden inside the meteorites. I also thought of "Corpus Earthling," an episode of The Outer Limits (original), but since that was about a scientist with a metal plate in his head that allowed him to listen to rocks plotting world domination, that was a totally different thing altogether. Well, mostly different. Well, at least the meteorites in They Came from Beyond Space and The Gods Hate Kansas didn't talk. A quick look trip back to IMDB confirmed my suspicion, that the film was indeed based on a book I didn't think anyone else besides me had ever read.

The Gods Hate Kansas was written by Joseph J. Millard (1908 - 1989) and first published in Startling Stories in 1941, then again in 1952 as a reprint in Fantastic Story Magazine. The version I read was a mass market paperback published by Monarch Books in 1964 with a very nice pulpish cover by Jack Thurston (1919 - 2017). Millard's flirtation with science fiction occupied only the first half of the Forties, after which he went on to be a teacher, and he confined his writing to westerns, memoirs, biographies, essays and poetry.

There are some differences between book and film, but when are there not? When David Morell's debut novel First Blood was optioned to be filmed as Rambo, the question of a sequel came up. Morell was perplexed by the idea. He asked, "How can there be a sequel when I've killed everyone off?" Older and wiser Hollywood hands told him, "If the movie is successful, there will be a sequel, no matter how they have to change your book. And the book will be changed. If they want to make it into a musical aboard a submarine, that's what they'll do." Fortunately, Rambo did not become an underwater musical, and neither were there any tremendous changes between The Gods Hate Kansas and They Came from Beyond Space.

The greatest changes are that the field is in England, not Kansas, and though the gods may still hate Kansas (more meteors fall there than anywhere else, according to the book) they don't hate England. The landing site still goes "dark" and the scientists begin acting weird. The metal plate is still in the main character's head and it still keeps him from being taken over by the aliens. The aliens are still tired of being marooned on the Moon and still want to use our planet's resources to escape their long imprisonment. And the moral of the story is still the same: "Why didn't you simply ask us for help?"

One other thing that's also the same -- the science. Millard was a good writer, but science was not his forte. When one of the aliens was told that no known propulsion system on earth could get a rocket to the Moon and back in less than 24 hours, the alien replies: "Our propulsion system was not developed on Earth." All in all, it's probably a good thing Millard found his calling in education and genres other than science fiction.

I have to admit, I did enjoy the film, but probably will not revisit it. That's something else the film has in common with the book.

If you're also into slightly cheesy science fiction, you might try my two steampunk novels, Shadows Against the Empire and Amidst Dark Satanic Mills . For the thousands who prefer not to do business with Amazon you can get Shadows Against the Empire and Amidst Dark Satanic Mills from your favorite e-book retailer or even ask your local library to stock them through Overdrive. For those who have already read the Folkestone & Hand Interplanetary Steampunk Adventures, a third book in the series, The Spirit-Haunted Moon will be published in 2020. Thanks for your support.

I thought, well, it could be an undiscovered gem or it might be dreck. Either way, it's 85 minutes. And I thought it would at least be passable, it being a British film. Yes, I know...I saw Devil Girl from Mars, but at least everyone had a British accent, and that automatically makes everything classier, such as when a developer names a housing development Robin Hood Estates rather than Pleasant Acres. But, then I recalled The Crawling Eye and how Tempean Films imported American actor Forrest Tucker (F Troop) to play the lead or how Hammer Films brought in Brian Donlevy to play the quintessential British scientist Professor Bernard Quatermass in the 1955 theatrical version of The Quatermass Experiment. So I gave in and took a sneak peek at IMDB: the lead actor is American Robert Hutton, but at least almost everyone will have a British accent. And it will still be 85 minutes. And I still had nothing else to do at the moment. So I queued the film and pressed start.

I thought, well, it could be an undiscovered gem or it might be dreck. Either way, it's 85 minutes. And I thought it would at least be passable, it being a British film. Yes, I know...I saw Devil Girl from Mars, but at least everyone had a British accent, and that automatically makes everything classier, such as when a developer names a housing development Robin Hood Estates rather than Pleasant Acres. But, then I recalled The Crawling Eye and how Tempean Films imported American actor Forrest Tucker (F Troop) to play the lead or how Hammer Films brought in Brian Donlevy to play the quintessential British scientist Professor Bernard Quatermass in the 1955 theatrical version of The Quatermass Experiment. So I gave in and took a sneak peek at IMDB: the lead actor is American Robert Hutton, but at least almost everyone will have a British accent. And it will still be 85 minutes. And I still had nothing else to do at the moment. So I queued the film and pressed start. From almost the beginning of the film, I got a sense of deja vu, but when you have seen as many films as I have (I bought the book Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, and it was like reading the story of my youth) it's a common feeling. About the time they mentioned meteorites falling in a field and Hutton's character having a metal plate in his head, I thought: The Gods Hate Kansas, in which meteorites fall in a Kansas field and a character has a metal plate in his head preventing him from being taken over by alien intelligences hidden inside the meteorites. I also thought of "Corpus Earthling," an episode of The Outer Limits (original), but since that was about a scientist with a metal plate in his head that allowed him to listen to rocks plotting world domination, that was a totally different thing altogether. Well, mostly different. Well, at least the meteorites in They Came from Beyond Space and The Gods Hate Kansas didn't talk. A quick look trip back to IMDB confirmed my suspicion, that the film was indeed based on a book I didn't think anyone else besides me had ever read.

From almost the beginning of the film, I got a sense of deja vu, but when you have seen as many films as I have (I bought the book Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, and it was like reading the story of my youth) it's a common feeling. About the time they mentioned meteorites falling in a field and Hutton's character having a metal plate in his head, I thought: The Gods Hate Kansas, in which meteorites fall in a Kansas field and a character has a metal plate in his head preventing him from being taken over by alien intelligences hidden inside the meteorites. I also thought of "Corpus Earthling," an episode of The Outer Limits (original), but since that was about a scientist with a metal plate in his head that allowed him to listen to rocks plotting world domination, that was a totally different thing altogether. Well, mostly different. Well, at least the meteorites in They Came from Beyond Space and The Gods Hate Kansas didn't talk. A quick look trip back to IMDB confirmed my suspicion, that the film was indeed based on a book I didn't think anyone else besides me had ever read.The Gods Hate Kansas was written by Joseph J. Millard (1908 - 1989) and first published in Startling Stories in 1941, then again in 1952 as a reprint in Fantastic Story Magazine. The version I read was a mass market paperback published by Monarch Books in 1964 with a very nice pulpish cover by Jack Thurston (1919 - 2017). Millard's flirtation with science fiction occupied only the first half of the Forties, after which he went on to be a teacher, and he confined his writing to westerns, memoirs, biographies, essays and poetry.

There are some differences between book and film, but when are there not? When David Morell's debut novel First Blood was optioned to be filmed as Rambo, the question of a sequel came up. Morell was perplexed by the idea. He asked, "How can there be a sequel when I've killed everyone off?" Older and wiser Hollywood hands told him, "If the movie is successful, there will be a sequel, no matter how they have to change your book. And the book will be changed. If they want to make it into a musical aboard a submarine, that's what they'll do." Fortunately, Rambo did not become an underwater musical, and neither were there any tremendous changes between The Gods Hate Kansas and They Came from Beyond Space.

The greatest changes are that the field is in England, not Kansas, and though the gods may still hate Kansas (more meteors fall there than anywhere else, according to the book) they don't hate England. The landing site still goes "dark" and the scientists begin acting weird. The metal plate is still in the main character's head and it still keeps him from being taken over by the aliens. The aliens are still tired of being marooned on the Moon and still want to use our planet's resources to escape their long imprisonment. And the moral of the story is still the same: "Why didn't you simply ask us for help?"

One other thing that's also the same -- the science. Millard was a good writer, but science was not his forte. When one of the aliens was told that no known propulsion system on earth could get a rocket to the Moon and back in less than 24 hours, the alien replies: "Our propulsion system was not developed on Earth." All in all, it's probably a good thing Millard found his calling in education and genres other than science fiction.

I have to admit, I did enjoy the film, but probably will not revisit it. That's something else the film has in common with the book.

If you're also into slightly cheesy science fiction, you might try my two steampunk novels, Shadows Against the Empire and Amidst Dark Satanic Mills . For the thousands who prefer not to do business with Amazon you can get Shadows Against the Empire and Amidst Dark Satanic Mills from your favorite e-book retailer or even ask your local library to stock them through Overdrive. For those who have already read the Folkestone & Hand Interplanetary Steampunk Adventures, a third book in the series, The Spirit-Haunted Moon will be published in 2020. Thanks for your support.

Published on September 07, 2019 11:10

July 11, 2019

As Time Goes By

It's been awhile since I last shared anything, but time passes no matter what we do. Our general sense of time is that it elapses at a steady, inexorable rate, second after second, each interval the same as the last. Let enough seconds elapse and we get a minute, enough minutes and we get hours, days, years, and then it's over. Paradoxically, you run out of time even as time continues its journey without you. No one can say, "Backward, turn backward, O Time, in your flight" (Hobart Brown), which may be one of the reasons why Time Travel is such a popular theme in Science Fiction, why many people would rather have a Time Machine than a Space Ship...well, I suppose you could get the TARDIS and have the best of both worlds.

My first introduction to the theme was the same as everyone else's: The Time Machine by H.G. Wells. I read it while in elementary school, probably not long after the 1960 George Pal film, still the best lensing of the book despite its many flaws.

The book affected me differently than did the film. For the film it was a matter of the monstrous Morlocks and the sheeply Eloi. I still recall vividly the menace of the Morlocks within the Winged Sphinx and the despair when the Time Traveler picked up a book in the Eloi library and it turned to dust. I think I found the Eloi more terrifying than the Morlocks. In the book, I was deeply affected by the vision of the far future, the Earth given over to Giant Crabs and darkness. Though Wells did not realize it at the time, he was envisioning what cosmologists now term the entropic death of the universe.

I returned to that far future when I wrote the Sherlock Holmes pastiche The Coils of Time. The book was written at the urging of Gary Lovisi at Gryphon Publications. When Hurricane Sandy put it out of print, I republished it in Sherlock Holmes: The Coils of Time & Other Stories. I also revisited the Time Traveler himself in a poem:

The Time TravellerTraveler without a name,Voyager on the river of Time,Where do you find yourself now?Do you stand by Pharaohâs hand,Or do saurians pursue youAcross a Jurassic land?Are you lost, wandering aimlesslyThrough the streets of ancient Rome?You designed a fine machine,Crafted from silver and brass,Crystal cut precise and hand-blown glass---So what went wrong?Were you arrested, executed;Did you catch the plague?Did you return to face the SphinxIn that savage land of gentle sheep?Weâre still waiting to hear your second tale,Perhaps even stranger than the first;Weâll always be waiting for you to pierce timeâs veil,To satisfy our mindâs chronic thirst;For now weâre ready to learn,We who forever await your belated return.

I recently included the above poem in a collection entitled Midnight for Schrödinger's Cat & Other Poems. In the collection, I not only wax eloquent about the mysteries of time and space, but quantum physics, horses, helium seas, alternate history, and a certain bad Friday in Jerusalem. Most are short, only a page or three, as is the nature of verse, but the titular poem is quite long, about fourteen pages.

Some of the poems appeared in my previous limited print editions, A Darkness on my Mind and The Horses of Byzantium & Other Poems. A few were previously printed in small/micro press journals, but the majority have never before been published, though they cover a period of more than thirty years. Even so, they don't comprise the entirety of my poetical flummery.

For those who patronize Amazon, click here to buy it in either print or digital formats. For those who say, "Anywhere but Amazon," you can click here to buy an e-book at anywhere but Amazon. Or use one of the buttons below.

Amazon:

Anywhere but Amazon:

However you get it, if you're moved to do so, I appreciate your support. As mentioned above, this eruption of verse does not exhaust my coffers, nor have I stopped writing poems in spare moments. When Holly takes me out on the patio for hours at a time and forces me to endlessly throw one of her balls for her to fetch (actually, she just drops it within reach -- I suspect that dog will never learn how to share), it does no good to get involved with reading or writing of any duration. So, there will eventually be yet another gathering of enigmatic verse. However, breathe easy. Do not panic. The world will be spared another collection this year, maybe the next as well. But I already have a cover...

Just a "friendly" warning...

Published on July 11, 2019 11:37

January 14, 2019

Not the Last Man Standing, But Close

The past is always better than the present, though when I was younger I thought the future would be better than the then-present. Then the future became the present, the present wasn't how we had envisioned the future (as I've written here earlier), and suddenly the past looked better than I remembered it being. I suppose that's why all the Golden Ages of anything (Novels, Short Stories, Magazines, Television, Hollywood, Comic Books, etc) are always in the past. Hesiod wrote that the Golden Age of Man, when Saturn (Kronos) ruled the Earth was a time of giants and perfect men and women, than when Saturn departed people became smaller, less perfect and heir to all the ills that plague us now.

I don't know if Hesiod was right or not. Maybe his Golden Age was more metaphorical than real, though there are some who claim Earth was once a satellite of the Ringed Planet, but got knocked into its present place in the Solar System when a rogue star turned the planets into snooker balls. I do know that "golden ages" are real in art, literature and personal life. I know of people who publish poetry in hopes that they will be recognized as the new Tennyson or Lord Byron; unfortunately, that ship sailed about a century ago, hit an iceberg with Frost and sank with the death of Angelou. There are now more people who write poetry than read it.

Comic books, too, aren't what they used to be. What was once exciting and vibrant, friendly and a pleasure to read, are now dismal, pessimistic, revisionist and about as uplifting as newspaper headlines. And most aren't even made in the USA anymore. The Golden Age of Television was in the Fifties and early Sixties, but when you actually see the old shows on DVD or Streaming, you have to wonder if maybe that Golden Age wasn't even as real as Hesiod's.

Which brings me to my own Golden Age. I started writing back in the Sixties, then with great earnest the following decade. The Eighties saw me get a foot in the door with magazines and publishers, and I made steady gains after that. I'm not famous, and I'm certainly not rich, but I can look back on a writing career that was as satisfying as it was frustrating, always battling with editors and occasionally finding a home for a story or a book. And I'm still at it, even though the small press has virtually vanished, no one wants submissions sent though the USPS, and most publications in this New Digital World are as ephemeral as a jarful of electrons. The amalgamation of publishers into a handful, the demise of all but one national bookselling chain (B&N is ever on the verge), and the rise of indie publishing as the new norm has changed everything, but that's not why my Golden Age is in the past.

It's people. It's writers and artists I've know, worked with and for, read, and sometimes even published in my own small press publications. Over the years, I've known hundreds to varying degrees. Some personally as friends and collaborators, others as correspondents, and more simply because I enjoyed their work and wrote to them. Where are they now? Gone, unfortunately; some are dead, but most simply moved on to something else, giving up the Grand Chase for fame and fortune.

So, out of the hundreds, who remains besides me? It's a small group. I can count them on one hand and have three fingers left over -- David Barker and Wilum Hopfrog Pugmire. All three of us are Lovecraft enthusiasts, but they have stayed closer to that essence than I have. I have to admire them, not just because they have stayed the course over the decades, but because they still have the fire that a writer must have. And they still write Lovecraftian tales. Recently they collaborated on a book entitled Witches in Dreamland, a novel set in Lovecraft's Dreamlands.

Witches in DreamlandIt's a magnificent book, well written and well plotted, beautifully produced by small press publisher Hippocampus Press. In addition to Lovecraft's universe, it also incorporates Willum's Sesqua Valley, in which he has set several stories, including one which I published and illustrated many years ago. Here's the pitch for the book:

Witches in DreamlandIt's a magnificent book, well written and well plotted, beautifully produced by small press publisher Hippocampus Press. In addition to Lovecraft's universe, it also incorporates Willum's Sesqua Valley, in which he has set several stories, including one which I published and illustrated many years ago. Here's the pitch for the book:

"Simon Gregory Williams, known as 'the beast' in Sesqua Valley, has been so corrupted by his reading and memorizing every existing edition of the Necronomicon that his tainted psyche cannot enter into Randolph Carterâs Dreamland. However, there is another dreamland, âthe dreamland of witches,â into which Simon can slink because of his brilliance as an alchemist; and it is into that dreamland that Simon accompanies an innocent young woman in her quest for rare magick. Yet even Simon, who is so experienced in eldritch lore, has never been so confronted by such outlandish Lovecraftian lunacy as he finds in this dreamland of witchery.

"In this fascinating excursion into the Lovecraftian fantasy/horror realm of Dreamland, two veteran authors of weird fiction have written a novel that is by turns horrific and poignant, with vibrant characters and a compelling narrative that carries the reader on from scene to scene to the novelâs cataclysmic conclusion."

I started on a grey note, which darkened as I wrote, but I hope ending on this high note, the publication of a new novel by two friends who deserve your attention and support, keeps this missive from being entirely a downer for you. For me, it's raining outside, the day is murky, and the house is too quiet. But, at some point in the future, if I live long enough, even this will seem part of some Golden Age...of what, I don't know, but something.

I don't know if Hesiod was right or not. Maybe his Golden Age was more metaphorical than real, though there are some who claim Earth was once a satellite of the Ringed Planet, but got knocked into its present place in the Solar System when a rogue star turned the planets into snooker balls. I do know that "golden ages" are real in art, literature and personal life. I know of people who publish poetry in hopes that they will be recognized as the new Tennyson or Lord Byron; unfortunately, that ship sailed about a century ago, hit an iceberg with Frost and sank with the death of Angelou. There are now more people who write poetry than read it.

Comic books, too, aren't what they used to be. What was once exciting and vibrant, friendly and a pleasure to read, are now dismal, pessimistic, revisionist and about as uplifting as newspaper headlines. And most aren't even made in the USA anymore. The Golden Age of Television was in the Fifties and early Sixties, but when you actually see the old shows on DVD or Streaming, you have to wonder if maybe that Golden Age wasn't even as real as Hesiod's.

Which brings me to my own Golden Age. I started writing back in the Sixties, then with great earnest the following decade. The Eighties saw me get a foot in the door with magazines and publishers, and I made steady gains after that. I'm not famous, and I'm certainly not rich, but I can look back on a writing career that was as satisfying as it was frustrating, always battling with editors and occasionally finding a home for a story or a book. And I'm still at it, even though the small press has virtually vanished, no one wants submissions sent though the USPS, and most publications in this New Digital World are as ephemeral as a jarful of electrons. The amalgamation of publishers into a handful, the demise of all but one national bookselling chain (B&N is ever on the verge), and the rise of indie publishing as the new norm has changed everything, but that's not why my Golden Age is in the past.

It's people. It's writers and artists I've know, worked with and for, read, and sometimes even published in my own small press publications. Over the years, I've known hundreds to varying degrees. Some personally as friends and collaborators, others as correspondents, and more simply because I enjoyed their work and wrote to them. Where are they now? Gone, unfortunately; some are dead, but most simply moved on to something else, giving up the Grand Chase for fame and fortune.

So, out of the hundreds, who remains besides me? It's a small group. I can count them on one hand and have three fingers left over -- David Barker and Wilum Hopfrog Pugmire. All three of us are Lovecraft enthusiasts, but they have stayed closer to that essence than I have. I have to admire them, not just because they have stayed the course over the decades, but because they still have the fire that a writer must have. And they still write Lovecraftian tales. Recently they collaborated on a book entitled Witches in Dreamland, a novel set in Lovecraft's Dreamlands.

Witches in DreamlandIt's a magnificent book, well written and well plotted, beautifully produced by small press publisher Hippocampus Press. In addition to Lovecraft's universe, it also incorporates Willum's Sesqua Valley, in which he has set several stories, including one which I published and illustrated many years ago. Here's the pitch for the book:

Witches in DreamlandIt's a magnificent book, well written and well plotted, beautifully produced by small press publisher Hippocampus Press. In addition to Lovecraft's universe, it also incorporates Willum's Sesqua Valley, in which he has set several stories, including one which I published and illustrated many years ago. Here's the pitch for the book:"Simon Gregory Williams, known as 'the beast' in Sesqua Valley, has been so corrupted by his reading and memorizing every existing edition of the Necronomicon that his tainted psyche cannot enter into Randolph Carterâs Dreamland. However, there is another dreamland, âthe dreamland of witches,â into which Simon can slink because of his brilliance as an alchemist; and it is into that dreamland that Simon accompanies an innocent young woman in her quest for rare magick. Yet even Simon, who is so experienced in eldritch lore, has never been so confronted by such outlandish Lovecraftian lunacy as he finds in this dreamland of witchery.

"In this fascinating excursion into the Lovecraftian fantasy/horror realm of Dreamland, two veteran authors of weird fiction have written a novel that is by turns horrific and poignant, with vibrant characters and a compelling narrative that carries the reader on from scene to scene to the novelâs cataclysmic conclusion."

I started on a grey note, which darkened as I wrote, but I hope ending on this high note, the publication of a new novel by two friends who deserve your attention and support, keeps this missive from being entirely a downer for you. For me, it's raining outside, the day is murky, and the house is too quiet. But, at some point in the future, if I live long enough, even this will seem part of some Golden Age...of what, I don't know, but something.

Published on January 14, 2019 11:42

October 18, 2018

Worlds of Maybe

In Worlds of Maybe, a 1970 anthology edited by Robert Silverberg, seven authors explore the idea of worlds where history took a different path than it did in our own world. "The writer makes his one, basic history-changing assumption; then he plunges his characters into a world that never was, and investigates all the imaginable consequences of that world's divergence from the 'real' time-line," Silverberg writes in his introduction. "The result, if the work is done intelligently and perceptively, is an excursion into speculative history, stimulating and strange."

In Worlds of Maybe, a 1970 anthology edited by Robert Silverberg, seven authors explore the idea of worlds where history took a different path than it did in our own world. "The writer makes his one, basic history-changing assumption; then he plunges his characters into a world that never was, and investigates all the imaginable consequences of that world's divergence from the 'real' time-line," Silverberg writes in his introduction. "The result, if the work is done intelligently and perceptively, is an excursion into speculative history, stimulating and strange."The results in this book are outstanding, but how could they be otherwise with such writers as Larry Niven, Isaac Asimov and Poul Anderson? It remains one of my favorite anthologies, and not just because of the theme. The oldest story in the book, Murray Leinster's "Sidewise in Time," is from 1934. While not the first alternate history story ever written -- that honor probably belongs to Ab Urbe Condita Libri by the Roman historian Livy, published in the First Century BC, in which Alexander the Great lives long enough to conquer Europe -- but it is the modern progenitor of the Alternate History sub-genre of Science Fiction, though it probably owes more than a nod to British historian Sir John Squire's 1931 book, If It Had Happened Otherwise, an anthology of essays from leading historians about the turning points of history. Since none of Sir John's contributors was an experienced fiction writer, the results are mostly interesting, but dry as yesterday's cracker and totally lacking in humor.

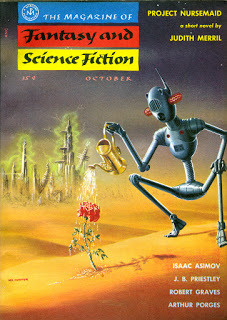

Another of my favorite Alternate History stories is Bring the Jubilee by Ward Moore, which I first encountered in an old edition of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, then later tracked down the paperback edition which expands upon the original story and brings in more characterization. It's a tale about what happened when the South won the Civil War, and yet it isn't. It uses a technique I call double-blind, in which it starts out in an alternate time-line where the Confederacy is an ascendant victor and the U.S. a backwater rump state, then introduces a variation via time travel, ending that time-line and starting history on a path that results in a world very much like our own, yet not quite. So, two separate worlds, neither our own, and yet exactly our own, since it is the very nature of Alternate History stories that no matter how odd the time-line is, it is always our world that is under scrutiny, just as Aliens in SF tales are never aliens, but merely different aspects of ourselves.

Another of my favorite Alternate History stories is Bring the Jubilee by Ward Moore, which I first encountered in an old edition of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, then later tracked down the paperback edition which expands upon the original story and brings in more characterization. It's a tale about what happened when the South won the Civil War, and yet it isn't. It uses a technique I call double-blind, in which it starts out in an alternate time-line where the Confederacy is an ascendant victor and the U.S. a backwater rump state, then introduces a variation via time travel, ending that time-line and starting history on a path that results in a world very much like our own, yet not quite. So, two separate worlds, neither our own, and yet exactly our own, since it is the very nature of Alternate History stories that no matter how odd the time-line is, it is always our world that is under scrutiny, just as Aliens in SF tales are never aliens, but merely different aspects of ourselves. An attempt to actually bring us an artifact from an alternate world was made by Norman Spinrad in The Iron Dream (1972), which, actually, is not the title of the book he wants us to read. The book presented for our reading "enjoyment" is Lord of the Swastika (1952), written by a science fiction fan and artist named Adolph Hitler, who emigrated from Germany in 1919 and became involved with First Fandom as an illustrator for the pulp magazines of the time. Spinrad's presentation of Hitler's pulse-pounding pulp story of a post-apocalyptic Earth is paired with a scholarly dissertation written by NYU Professor Homer Whipple in 1959, in which he examines the influence of the Hugo-winning novel on fandom, as well as taking a look at Hitler's other science fiction novels -- The Master Race, The Thousand Year Rule, and The Triumph of the Will, all titles that will resonate in much different ways for readers in this time-line than they will in Whipple's, but that is as intended. The same is true of the novel itself, as we will see much darker themes than did Hitler's readers, to whom it is nothing more than an exciting story, worthy of receiving that year's Hugo award. The book is a curiosity, nothing more, because the story itself becomes tedious after awhile. The most interesting portion of Spinrad's book is the dry and pedantic essay by Whipple, where we have tantalizing glimpses and suggestions of a strange new world, teases which remain unfulfilled.

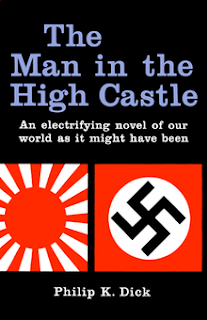

An attempt to actually bring us an artifact from an alternate world was made by Norman Spinrad in The Iron Dream (1972), which, actually, is not the title of the book he wants us to read. The book presented for our reading "enjoyment" is Lord of the Swastika (1952), written by a science fiction fan and artist named Adolph Hitler, who emigrated from Germany in 1919 and became involved with First Fandom as an illustrator for the pulp magazines of the time. Spinrad's presentation of Hitler's pulse-pounding pulp story of a post-apocalyptic Earth is paired with a scholarly dissertation written by NYU Professor Homer Whipple in 1959, in which he examines the influence of the Hugo-winning novel on fandom, as well as taking a look at Hitler's other science fiction novels -- The Master Race, The Thousand Year Rule, and The Triumph of the Will, all titles that will resonate in much different ways for readers in this time-line than they will in Whipple's, but that is as intended. The same is true of the novel itself, as we will see much darker themes than did Hitler's readers, to whom it is nothing more than an exciting story, worthy of receiving that year's Hugo award. The book is a curiosity, nothing more, because the story itself becomes tedious after awhile. The most interesting portion of Spinrad's book is the dry and pedantic essay by Whipple, where we have tantalizing glimpses and suggestions of a strange new world, teases which remain unfulfilled.Despite the popularity of the Alternate History theme with SF fans, it remained obscure among non-fans. Possibly it was too esoteric or demanded too much thinking. The general public got a big dose of it with the television series Sliders, a show that started well, then swiftly deteriorated. The various iterations of Star Trek dipped a toe into the waters of Change with "Mirror Universe" in Star Trek: The Original Series (also in DS9 and Enterprise); then a cannonball into the swimming pool of Change with a reboot of the franchise, a move that pandered to younger fans but has not yet produced any decent films. Literary critics took notice of the genre and Science Fiction in general with Philip K. Dick's 1962 The Man in the High Castle ("This book is too good to be science fiction," the critics said), but did not make it to the masses till Amazon's take on it began streaming into homes in 2015. The book was great; the adaptation of it, not so much.

Notice, the absence of the words "Science Fiction"

Notice, the absence of the words "Science Fiction" from the hardcover edition of Dick's novel.

An appeal to Literary Critics?

Published on October 18, 2018 11:42

October 5, 2018

It Was My Mother's Fault

When I was young, there were three magazines I could always count on finding around the house -- True Story, True Detective and Fate.

When I was young, there were three magazines I could always count on finding around the house -- True Story, True Detective and Fate.

True Story, started in 1919, part of a genre called confession stories, tales usually written in the first person, telling of emotionally charged situations and romances. At the time, I thought the magazine lived up to its name and the the "confessions" were true. Happily, they were fiction. Of the three magazines, it was the only one I had to read on the sly. It wasn't so much that it actually contained naughty stories (compared to today's standards they were sparkling clean) but that they addressed subjects such as infidelity, alcoholism and all the other facets of life that gossiping neighbors only spoke of in whispers, and only after making sure no young ears were present...hey, I was good at not being noticed. My nose may have been stuck in a book, but my ears were quivering. So, even though my mother never told me I could not read them, I knew enough not to get caught. Admittedly, my sheltered upbringing meant that much of what went on in the stories was incomprehensible to me, but, even so, the stories were compelling. The magazine is still around, but I assume its fiction has kept pace with the times, unfortunately.

True Detective was probably the best of the true crime magazines that proliferated during the Forties and Fifties, and my mother always had plenty on hand. Even back then, I was an aficionado of crime, a budding criminologist. When I opened my first detective agency at age nine, it was inspired equally by Sherlock Holmes and True Detective. While I may have been confused about the veracity of confession stories, I harbored no such doubt about the reports of murder, robberies and sex crimes found in the pages of True Detective. I appeared in the magazine in the very early Sixties. One of the stories, a murder, I think, took place in National City and the newspaper reporter (the magazine provided a nice second income for crime journalists and literate police officers) submitted several photographs to illustrate the article. In one of the photos, there we are, Aunt Joyce and me, crossing Highland Avenue at 15th Street. Aunt Joyce attended National City Junior High her walk home took her past Highland (now Otis) Elementary, and sometimes we would end up walking together...my grandparents lived down the street from us on E. 17th Street. My grandmother, also an avid reader of such magazines, discovered the photo and promptly called my mother. They were both appalled their children had appeared, even as innocent bystanders, in such a magazine, but Joyce and I were thrilled. Unfortunately, True Detective did not survive into the 21st Century, coming to an end in the mid-Nineties. The demise of the magazine was explained by former True Detective managing editor Marc Gerald: “...our readership of blue hairs, shut-ins, Greyhound bus riders, cops and ax murderers was old and dying fast.”

True Detective was probably the best of the true crime magazines that proliferated during the Forties and Fifties, and my mother always had plenty on hand. Even back then, I was an aficionado of crime, a budding criminologist. When I opened my first detective agency at age nine, it was inspired equally by Sherlock Holmes and True Detective. While I may have been confused about the veracity of confession stories, I harbored no such doubt about the reports of murder, robberies and sex crimes found in the pages of True Detective. I appeared in the magazine in the very early Sixties. One of the stories, a murder, I think, took place in National City and the newspaper reporter (the magazine provided a nice second income for crime journalists and literate police officers) submitted several photographs to illustrate the article. In one of the photos, there we are, Aunt Joyce and me, crossing Highland Avenue at 15th Street. Aunt Joyce attended National City Junior High her walk home took her past Highland (now Otis) Elementary, and sometimes we would end up walking together...my grandparents lived down the street from us on E. 17th Street. My grandmother, also an avid reader of such magazines, discovered the photo and promptly called my mother. They were both appalled their children had appeared, even as innocent bystanders, in such a magazine, but Joyce and I were thrilled. Unfortunately, True Detective did not survive into the 21st Century, coming to an end in the mid-Nineties. The demise of the magazine was explained by former True Detective managing editor Marc Gerald: “...our readership of blue hairs, shut-ins, Greyhound bus riders, cops and ax murderers was old and dying fast.”

Fate Magazine is another periodical that has survived into this strange new century, and of the three magazines probably had the most effect on me and my writing. Even today, I sometimes peruse my copies from the Fifties and Sixties for inspiration. The purpose of Fate remains unchanged after 60 years and four owners -- reveal the strange true mysteries of the world, such as UFOs, cryptozology, psychic phenomena, ghosts, lost civilizations and the like. As you can see, the covers have changed over the years, but the content remains uniform. I like the art covers, but by the time I came across my mother's stash, the magazine had switched to the type of cover depicted in the center. While I don't personally care for the modern photo cover it was in one of those issues that my story about the Hohokam Indians appeared, an article that led to a 2-hour interview on a Phoenix radio station.

Occasionally I am asked about influences upon my writing. Of course I mention my favorite writers, such as Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, Raymond Chandler and Joseph Conrad, and the many books such as Moby Dick, Atlas Shrugged and At the Mountains of Madness. I also mention the events of my own life such as serving in the military, riding trains around Europe, and experiencing tragic losses. But I also have to give a nod to these three magazines, publications that many might call "trashy." But I really don't feel responsible for these dubious influences -- it was my mother's fault.

Published on October 05, 2018 00:18

September 25, 2018

The Lonely Robot

A lone (and lonely) robot wandered through my youth, and I found myself fascinated by his journeys through a landscape bereft of humans. I also find myself at times identifying with his solitary sojourn. The Lonely Robot was the creation of artist Mel Hunter (27 July 1927 - 20 Feb 2004) and his long walkabout was chronicled on the covers of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (F&SF). It began in 1955 (left) when readers saw the sleek metallic form watering a single rose in a wasteland, an image lifted for a popular Disney film decades later. We don't know how the world of the Lonely Robot got into the state it was, but the radioactive glimmer on the city in the background is certainly suggestive.

A lone (and lonely) robot wandered through my youth, and I found myself fascinated by his journeys through a landscape bereft of humans. I also find myself at times identifying with his solitary sojourn. The Lonely Robot was the creation of artist Mel Hunter (27 July 1927 - 20 Feb 2004) and his long walkabout was chronicled on the covers of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (F&SF). It began in 1955 (left) when readers saw the sleek metallic form watering a single rose in a wasteland, an image lifted for a popular Disney film decades later. We don't know how the world of the Lonely Robot got into the state it was, but the radioactive glimmer on the city in the background is certainly suggestive.Hunter was a very popular artist, mostly self-taught after escaping an abusive childhood and fleeing to NYC. His interest in space, science, aviation and astronomical subjects made him a natural for the science fiction magazines at the time. His clean lines and angular shapes have a very "retro" look to them these days, the future as imagined by a technophile. Even the robot looks as if he escaped from the laboratory of a B-movie Mad Scientist in the Fifties. In addition to SF magazines, Hunter also produced illustrations for mainstream magazines, science publications, the aviation industry, and observatories and academic organizations.

As the Lonely Robot journeyed through the world that used to belong to humans, we see him engage in some very human activities, such as pitching a baseball, driving a dune buggy, and playing with some wind-up toys. In a poignant moment, we see him donning a Santa Claus suit against the backdrop of a ruined city with a copy of A Christmas Carol on the ground and a single bright star high in the sky. All the paintings have a sense of humor to them, but the most effective and understated image showed the Lonely Robot standing at the corner of an intersection in a ruined town, hands on hips, gazing upward at a pedestrian signal that refuses to change from Wait to Walk. Obviously, no scofflaw is our Lonely Robot. My favorite illustration, however, the one that resonated with my own situation, and maybe some anxieties, is the one to the right. The bookcase extending from a dune suggests a library that has lost its outer shell or perhaps a bookstore. Or, maybe, since all the covers of the F&SF issues stacked on the ground were familiar to me, perhaps they were mine and he was sitting in what was left of my room. Maybe.

As the Lonely Robot journeyed through the world that used to belong to humans, we see him engage in some very human activities, such as pitching a baseball, driving a dune buggy, and playing with some wind-up toys. In a poignant moment, we see him donning a Santa Claus suit against the backdrop of a ruined city with a copy of A Christmas Carol on the ground and a single bright star high in the sky. All the paintings have a sense of humor to them, but the most effective and understated image showed the Lonely Robot standing at the corner of an intersection in a ruined town, hands on hips, gazing upward at a pedestrian signal that refuses to change from Wait to Walk. Obviously, no scofflaw is our Lonely Robot. My favorite illustration, however, the one that resonated with my own situation, and maybe some anxieties, is the one to the right. The bookcase extending from a dune suggests a library that has lost its outer shell or perhaps a bookstore. Or, maybe, since all the covers of the F&SF issues stacked on the ground were familiar to me, perhaps they were mine and he was sitting in what was left of my room. Maybe.

Published on September 25, 2018 10:46

August 16, 2018

Ravyn vs Magic

The fourth book in the DCI Arthur Ravyn Mystery series, Murderer in Shadow, is now available. This time DCI Ravyn and DS Stark find themselves in the village of Knight's Crossing, where magic is an everyday part of life...and death. The search for a missing boy leads to the reopening of the Stryker Case, the murder of a family of malevolent magicians more than three decades earlier. For those who'd like a little peak at the story (best viewed full screen)...

Though the magical universe as portrayed in the novel does have some Lovecraftian underpinnings, it's actually based on "real" magical systems used by magicians and sorcerers. Though I don't write many fantasy stories, except the Kira Series and the Cthulhu Mythos stories (which I treat, really, as science fiction and/or mystery), I still conduct reams of research, to the point where less than 10% of the research actually makes it into the story. In crafting the worldview of the villagers of Knight's Crossing I used perhaps a dozen reference books, but three in particular.

Just because something isn't real doesn't mean it shouldn't be exhaustively researched. In my early years (pre-junior high school), that penchant tended to hold me back. I found it hard to write about subjects I could not describe right down to the nuts and bolts, such as time machines and faster-than-light spaceships. Fortunately, I learned I didn't have to tell the reader how to build one in order to get him to believe it was real in the context of the story. Though Murderer in Shadow is not a fantasy story, it does have some fantastic elements, especially for the down-to-earth Detective Sergeant Leo Stark.

Anyway, it feels good to have Ravyn and Stark back on the job protecting victims, nicking villains, and balancing the letter of the law with the spirit of the law. Though Arthur Ravyn would certainly downplay their importance in the scheme of things, one shudders to think what chaos their absence would cause in Hammershire County, a place where change comes slowly, if at all, the past often intrudes upon the present and old things sometimes refuse to die.

Though the magical universe as portrayed in the novel does have some Lovecraftian underpinnings, it's actually based on "real" magical systems used by magicians and sorcerers. Though I don't write many fantasy stories, except the Kira Series and the Cthulhu Mythos stories (which I treat, really, as science fiction and/or mystery), I still conduct reams of research, to the point where less than 10% of the research actually makes it into the story. In crafting the worldview of the villagers of Knight's Crossing I used perhaps a dozen reference books, but three in particular.

Just because something isn't real doesn't mean it shouldn't be exhaustively researched. In my early years (pre-junior high school), that penchant tended to hold me back. I found it hard to write about subjects I could not describe right down to the nuts and bolts, such as time machines and faster-than-light spaceships. Fortunately, I learned I didn't have to tell the reader how to build one in order to get him to believe it was real in the context of the story. Though Murderer in Shadow is not a fantasy story, it does have some fantastic elements, especially for the down-to-earth Detective Sergeant Leo Stark.

Anyway, it feels good to have Ravyn and Stark back on the job protecting victims, nicking villains, and balancing the letter of the law with the spirit of the law. Though Arthur Ravyn would certainly downplay their importance in the scheme of things, one shudders to think what chaos their absence would cause in Hammershire County, a place where change comes slowly, if at all, the past often intrudes upon the present and old things sometimes refuse to die.

Published on August 16, 2018 11:31

August 12, 2018

It's Obvious Now, But Back Then...

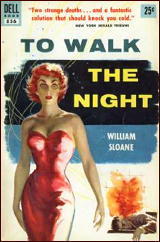

A modern reader coming upon William Sloane's novel To Walk the Night will know almost from the outset what's going on -- an inter-dimensional being taking over a human body and using it to explore our mundane world. After all, we've seen the same situation in dozens of films and in even more books. Sometimes we call them inter-dimensional beings, sometimes aliens; at times we even call them demons as William Peter Blatty did. But Sloane's novel does not have behind it a corpus of literary traditions for it was published in 1937. Just a year before, HP Lovecraft published The Shadow Out of Time, also the story of a human taken over by a non-human intellect, but the reader of the day was mostly ignorant of science fiction, except, of course, for that "crazy Buck Rogers stuff."

In those days before genres came to dominate all, authors and publishers could sometimes walk the line between literary forms. There is no doubt that To Walk the Night is a science fiction novel with overtones of cosmic horror, but it also has a locked room murder mystery. I doubt there was much hope in 1937 in marketing it as a science fiction novel. Instead, the publisher put it forth as a mystery novel. Readers liked his writing but were confused, as were critics of the day.

In those days before genres came to dominate all, authors and publishers could sometimes walk the line between literary forms. There is no doubt that To Walk the Night is a science fiction novel with overtones of cosmic horror, but it also has a locked room murder mystery. I doubt there was much hope in 1937 in marketing it as a science fiction novel. Instead, the publisher put it forth as a mystery novel. Readers liked his writing but were confused, as were critics of the day.

Now, there's nothing really wrong with making that call. I could certainly mount a good argument in favor of it -- locked room murder, a missing girl, a complex cosmic puzzle to be solved with lots of clues and red herrings. Ultimately, however, it is a science fiction novel. The strongest argument of it being a mystery, the locked room murder, is solved toward the end with a tossed-off comment that makes perfect sense within the context of the novel, but none at all outside it. An idiot (clinical term) is missing but the reader knows immediately that the missing girl and the dead professor's mysterious wife are the same person, though everyone in the book seems baffled. As to the solution of the complex cosmic puzzle, we know it almost as soon as we get all the characters sorted out, but we listen simply for the sheer beauty and power of Sloane's writing.

The pacing is a little slow for modern tastes, but anyone who watched British films such as Night of the Demon or Night of the Eagle (Burn, Witch, Burn!) will appreciate its subtle approach, its sense of mounting horror. Get sucked into the story and you'll even forget that you know more what's going on than the characters.

The book is out of print, but is, I think, available in digital format. It was also published with another of Sloane's mystery/science fiction/horror novels, The Edge of Running Water under the omnibus title The Rim of Morning, an edition well worth hunting for.

In those days before genres came to dominate all, authors and publishers could sometimes walk the line between literary forms. There is no doubt that To Walk the Night is a science fiction novel with overtones of cosmic horror, but it also has a locked room murder mystery. I doubt there was much hope in 1937 in marketing it as a science fiction novel. Instead, the publisher put it forth as a mystery novel. Readers liked his writing but were confused, as were critics of the day.

In those days before genres came to dominate all, authors and publishers could sometimes walk the line between literary forms. There is no doubt that To Walk the Night is a science fiction novel with overtones of cosmic horror, but it also has a locked room murder mystery. I doubt there was much hope in 1937 in marketing it as a science fiction novel. Instead, the publisher put it forth as a mystery novel. Readers liked his writing but were confused, as were critics of the day.Now, there's nothing really wrong with making that call. I could certainly mount a good argument in favor of it -- locked room murder, a missing girl, a complex cosmic puzzle to be solved with lots of clues and red herrings. Ultimately, however, it is a science fiction novel. The strongest argument of it being a mystery, the locked room murder, is solved toward the end with a tossed-off comment that makes perfect sense within the context of the novel, but none at all outside it. An idiot (clinical term) is missing but the reader knows immediately that the missing girl and the dead professor's mysterious wife are the same person, though everyone in the book seems baffled. As to the solution of the complex cosmic puzzle, we know it almost as soon as we get all the characters sorted out, but we listen simply for the sheer beauty and power of Sloane's writing.

The pacing is a little slow for modern tastes, but anyone who watched British films such as Night of the Demon or Night of the Eagle (Burn, Witch, Burn!) will appreciate its subtle approach, its sense of mounting horror. Get sucked into the story and you'll even forget that you know more what's going on than the characters.

The book is out of print, but is, I think, available in digital format. It was also published with another of Sloane's mystery/science fiction/horror novels, The Edge of Running Water under the omnibus title The Rim of Morning, an edition well worth hunting for.

Published on August 12, 2018 23:33

January 22, 2018

Killing Cousins, and More

I read a few chapters from a book, then move on to another, a dozen or two per day, e-books and real, but not always the same books day to day. Others are confused when I explain my reading habits, but I never get confused about who's who or what's happened when I return for another few chapters, even if some days or weeks have elapsed since my last trip into that fictional realm. Yes, fiction is not at all like real life, where I find myself confused most of the time.

My only rule is not to read two books by the same author at the "same" time. Recently, I found myself reading two books by different authors, Beware of the Dog (A Virginia and Felix Mystery) by E.X. Ferrars and Twice in a Blue Moon (An Inspector Henry Tibbett Mystery) by Patricia Moyes. Both books are set in England and both are murder mysteries, but Beware of the Dog is an amateur detective mystery, told by Virginia of her sleuthing husband (estranged and not entirely trustworthy), while Twice in a Blue Moon is a police procedural, even if the point of view is that of a character slightly removed from the actual investigation. What tied the books together and what set me to pondering was their theme. Both involve inheritances and long-separated cousins. I won't reveal spoilers in case you want to read the books (both are excellent), but let's just say that when it comes to cousins, blood may not be thicker than water. I thought back over other books and stories I've read, films and television shows I've seen, and realized that when it comes to crime fiction it pays to be wary of one's cousins.

My only rule is not to read two books by the same author at the "same" time. Recently, I found myself reading two books by different authors, Beware of the Dog (A Virginia and Felix Mystery) by E.X. Ferrars and Twice in a Blue Moon (An Inspector Henry Tibbett Mystery) by Patricia Moyes. Both books are set in England and both are murder mysteries, but Beware of the Dog is an amateur detective mystery, told by Virginia of her sleuthing husband (estranged and not entirely trustworthy), while Twice in a Blue Moon is a police procedural, even if the point of view is that of a character slightly removed from the actual investigation. What tied the books together and what set me to pondering was their theme. Both involve inheritances and long-separated cousins. I won't reveal spoilers in case you want to read the books (both are excellent), but let's just say that when it comes to cousins, blood may not be thicker than water. I thought back over other books and stories I've read, films and television shows I've seen, and realized that when it comes to crime fiction it pays to be wary of one's cousins.

Cousins usually don't fare well when they make appearances in crime friction. As you can see from the samples above, some writers just can't resist turning "kissing cousins" into "killing cousins." It's a good thing titles can't be copyrighted. Whenever a cousin turns up in crime fiction, it's a good idea to keep an eye on him, and cousins in such books would be well advised to sleep with one eye open. I'm not sure why mystery writers are so hard on cousins, but it may be because they're not often as close as siblings, sometimes not much better than strangers. It may also speak to motivation because cousins don't seem to find their way back into the fold till money comes into the picture, as in the case of both books that set me thinking about cousins in mystery fiction. Prodigal cousins are dangerous, but murder may be in the offing if you get too many cousins gathered in one place, as in this classic from Douglas Browne:

Considering how often the Grim Reaper visits cousins in mysteries, or how frequently the hidden killer turns out to be long-lost Cousin Roger, whom no has seen since Uncle Darby and Aunt Joan emigrated to Australia years ago, it's odd there is no specific word for killing one's cousin. I was greatly surprised when I searched for such a word and came up short. But I did pick up some grimly fascinating linguistic gems along the way.

Almost all "killing" words end in -cide, from the Latin for "kill." For example, there's suicide, the killing of one's self and homicide, the murder of a person. We also have wives who kill husbands (matricide) and husbands who kill wives (uxorcide), as well as parents who just can't stand the kids anymore (filicide for son or daughter, prolicide for both), deadly siblings (fratricide for killing a brother, sorocide for a sister), and even nepotcide when it comes time to get rid of the not-so-favorite nephew when disinheriting is not enough. A murderous guest or host can do each other in with hospiticide, and you can eliminate that annoying senior citizen in your life with senicide. You can kill bees with apicide, not to be confused with apricide, which is killing a boar. And when I goof around, doing nothing in particular, I'm committing chronicde, killing time. But, as unbelievable as it may seem, there is absolutely no word in the English language for killing one's cousin, so I propose "cognicide," from "cognata," Latin for cousin...or am I guilty of linguicide -- killing language?

My only rule is not to read two books by the same author at the "same" time. Recently, I found myself reading two books by different authors, Beware of the Dog (A Virginia and Felix Mystery) by E.X. Ferrars and Twice in a Blue Moon (An Inspector Henry Tibbett Mystery) by Patricia Moyes. Both books are set in England and both are murder mysteries, but Beware of the Dog is an amateur detective mystery, told by Virginia of her sleuthing husband (estranged and not entirely trustworthy), while Twice in a Blue Moon is a police procedural, even if the point of view is that of a character slightly removed from the actual investigation. What tied the books together and what set me to pondering was their theme. Both involve inheritances and long-separated cousins. I won't reveal spoilers in case you want to read the books (both are excellent), but let's just say that when it comes to cousins, blood may not be thicker than water. I thought back over other books and stories I've read, films and television shows I've seen, and realized that when it comes to crime fiction it pays to be wary of one's cousins.

My only rule is not to read two books by the same author at the "same" time. Recently, I found myself reading two books by different authors, Beware of the Dog (A Virginia and Felix Mystery) by E.X. Ferrars and Twice in a Blue Moon (An Inspector Henry Tibbett Mystery) by Patricia Moyes. Both books are set in England and both are murder mysteries, but Beware of the Dog is an amateur detective mystery, told by Virginia of her sleuthing husband (estranged and not entirely trustworthy), while Twice in a Blue Moon is a police procedural, even if the point of view is that of a character slightly removed from the actual investigation. What tied the books together and what set me to pondering was their theme. Both involve inheritances and long-separated cousins. I won't reveal spoilers in case you want to read the books (both are excellent), but let's just say that when it comes to cousins, blood may not be thicker than water. I thought back over other books and stories I've read, films and television shows I've seen, and realized that when it comes to crime fiction it pays to be wary of one's cousins.

Cousins usually don't fare well when they make appearances in crime friction. As you can see from the samples above, some writers just can't resist turning "kissing cousins" into "killing cousins." It's a good thing titles can't be copyrighted. Whenever a cousin turns up in crime fiction, it's a good idea to keep an eye on him, and cousins in such books would be well advised to sleep with one eye open. I'm not sure why mystery writers are so hard on cousins, but it may be because they're not often as close as siblings, sometimes not much better than strangers. It may also speak to motivation because cousins don't seem to find their way back into the fold till money comes into the picture, as in the case of both books that set me thinking about cousins in mystery fiction. Prodigal cousins are dangerous, but murder may be in the offing if you get too many cousins gathered in one place, as in this classic from Douglas Browne:

Considering how often the Grim Reaper visits cousins in mysteries, or how frequently the hidden killer turns out to be long-lost Cousin Roger, whom no has seen since Uncle Darby and Aunt Joan emigrated to Australia years ago, it's odd there is no specific word for killing one's cousin. I was greatly surprised when I searched for such a word and came up short. But I did pick up some grimly fascinating linguistic gems along the way.

Almost all "killing" words end in -cide, from the Latin for "kill." For example, there's suicide, the killing of one's self and homicide, the murder of a person. We also have wives who kill husbands (matricide) and husbands who kill wives (uxorcide), as well as parents who just can't stand the kids anymore (filicide for son or daughter, prolicide for both), deadly siblings (fratricide for killing a brother, sorocide for a sister), and even nepotcide when it comes time to get rid of the not-so-favorite nephew when disinheriting is not enough. A murderous guest or host can do each other in with hospiticide, and you can eliminate that annoying senior citizen in your life with senicide. You can kill bees with apicide, not to be confused with apricide, which is killing a boar. And when I goof around, doing nothing in particular, I'm committing chronicde, killing time. But, as unbelievable as it may seem, there is absolutely no word in the English language for killing one's cousin, so I propose "cognicide," from "cognata," Latin for cousin...or am I guilty of linguicide -- killing language?

Published on January 22, 2018 11:23