Ralph E. Vaughan's Blog, page 10

November 8, 2012

Bram Stoker & His Count...Both Going Strong

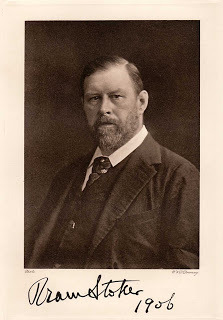

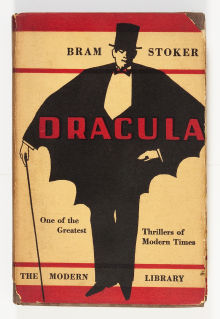

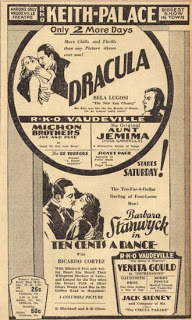

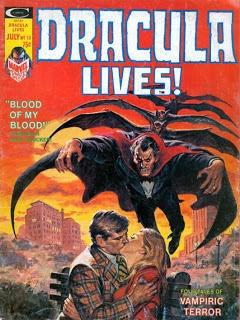

Irish writer Abraham "Bram" Stoker (8 Nov 1847 - 20 Apr 1912) turns 165 today, but his popularity has not waned with the passing of the years. Although his fame might not equal that of his literary creation, he has achieved the sort of immortality for which many writers strive but few achieve. It's a particularly remarkable feat when you consider that his fame rests upon a single novel, Dracula. Although he wrote a dozen novels during his career, eight of them were flighty romances of the sort popular in the Victorian Era, and, of the remaining four, three were supernatural or horror tales with a strong streak of romance running through them; there is only one Dracula.

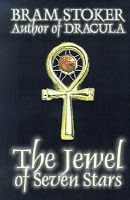

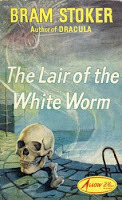

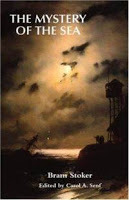

His book The Mystery of the Sea is quite interesting for its maritime mood and dark atmosphere. And his novels The Lair of the White Worm and The Jewell of the Seven Stars (both made into films of dubious quality) are notable for their treatments of ancient legends, one Egyptian, the other British. The Jewell of the Seven Stars, in particular, was quite controversial for its gruesome ending, which his publisher demanded be changed before a reprinting could be considered. But, as well written and well intended as the books are, none of them are Dracula, a book which Stoker researched seven years before sending young solicitor Jonathan Harker in the wilds of the Carpathian Mountains in search of Count Dracula's crumbling castle.

Unfortunately, for modern readers, Dracula suffers much the same fate as young Mary Shelly's Frankenstein, in that most people know it by its cinematic avatars and not by the book itself. Even those fans who bought one of the many editions available sometimes must admit to never having actually read it, which is a shame, because it is not only a well-written novel but is told using a format that allows for multiple points of view and layers unusual for a book of its period. It's a novel whose plot is revealed though letters and diary entries written by characters who have varying viewpoints and levels of understanding about the other characters and the events which are touching their lives. Interspersed among these accounts are newspaper clippings written by others who are not involved in the story, adding not only an aspect of objectivity but also of ignorance, which makes the reader feel even more privy to the events. The book is given a patina of realism and verisimilitude by removing Bram Stoker from the position of author within the context of the story and relegating him to the role of editor, the man who gathers together all these disparate writings and tries to make sense of them. Even though sales of the book were not as brisk as hoped when it was first published in 1897, they remained steady and increasing, and the book has not been out of print since.

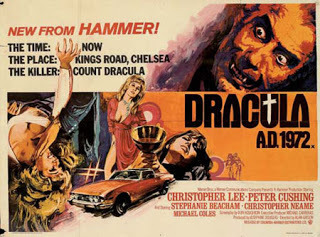

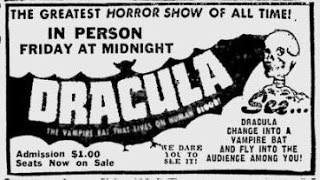

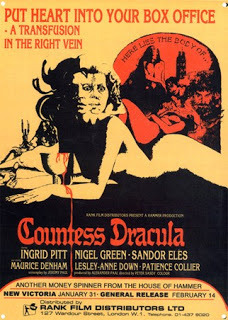

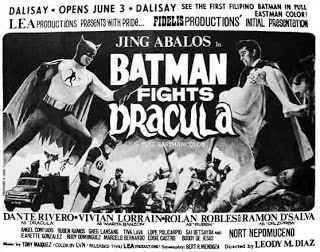

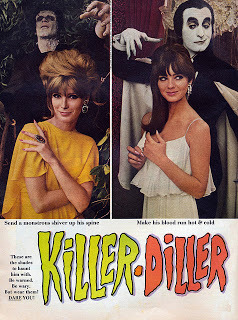

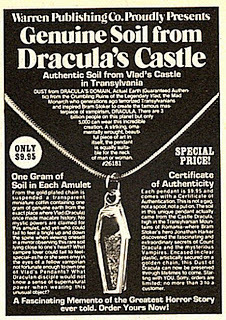

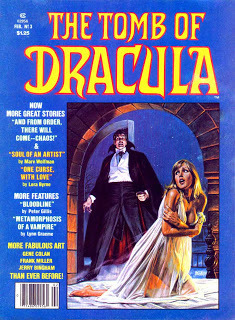

But, as mentioned, most people know Dracula from his many appearance on stage, screen and television. If Dracula was Bram Stoker's gift to the world, it is the gift that keeps on giving. We have seen Dracula reborn time after time, despite being staked, beheaded and incinerated. He has fought the Wolfman, Billy the Kid, Sherlock Holmes, and even Batman; Buffy the Vampire Slayer had her shot at him, as did the Flintstones and The Munsters. In the series Sliders, when the gang "slid" into an alternate Earth where vampirism had been illegal since 1865, they encountered a rock band appropriately called Stoker. Like Dracula himself, just when you think you have heard the last of him (and vampires) yet another avatar comes rushing into the public consciousness. Who will die first, Bram Stoker or Dracula? Sorry, we're not taking any bets.

Published on November 08, 2012 15:07

October 13, 2012

Of Dogs, Robots, Pantropy and Cities...

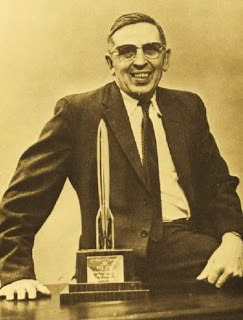

Clifford Simak, older & wiser

Clifford Simak, older & wiser

Clifford Simak, young writer

Clifford Simak, young writerGrown men and women, sixty years old, twenty‑five years old, sit around and talk about the "golden age of science fiction," remembering when every story in every magazine was a masterwork of daring, original thought. Some say the golden age was circa 1928; some say 1939; some favor 1953, or 1970, or 1984. The arguments rage till the small of morning, and nothing is ever resolved. Because the real golden age of science fiction is twelve ....Twelve may be the golden age for science fiction but it started a bit earlier with me, and lasted a little longer, till at least my late forties, when I finally realized that whenever the golden age of science fiction was, it was certainly in the past, and the past is that which is forever lost. It was then that I looked at the state of modern science fiction and saw how little of it actually appealed to me -- comic book spin-offs, feminist fantasy, endless bland sequels of original novels that were bland to begin with, ideological and political treatises disguised as fiction, and tomes of jaded snarkiness written by clueless university graduates ensnared by cultural memes and tropes. I still read some science fiction these days, but, like me, it tends to be older, and just recently I re-read what may be the best science fiction novel ever written, though, technically, it's not a novel at all, but a collection of eight, sometimes nine, short stories.—Peter Graham

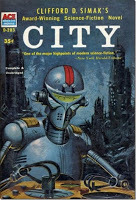

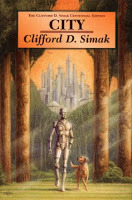

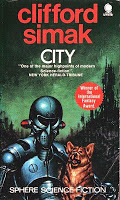

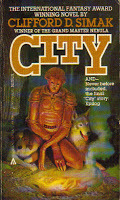

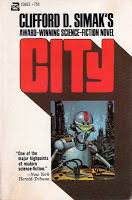

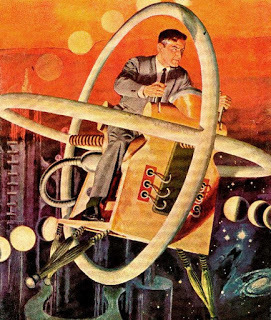

I first encountered City by Clifford Simak (1904 - 1988) in the very early 60s, in one of the many charity shops I frequented as a wayward youth looking for old books and magazines, squandering an allowance that can only be described as impecunious. It was the Ace paperback edition (D-283), published in 1958, featuring what was to my mind (then and now) the coolest robot ever (even better that those in Gold Key's Magus, Robot Fighter), painted by our pal Ed Valigursky, the uber-talented artist we've considered elsewhere in these pages. Very much an image of the 50s, with its knobs and dials, it's such a potent depiction that it was reused in later editions, or reworked to form similar covers for foreign printings. Of the 79 paintings Ed Valigursky did for Ace Books, this tops all of them. It sticks in the mind, and can even invade dreams. As good as this painting is, though, the story it illustrates is much better.

As mentioned earlier, it's not a novel proper, but a collection of stories (appearing in magazines from 1944 to 1951), which are tied together not just through theme and character, but via a preface and story notes written by the "editor," who is a dog. The beginning of the book is unforgettable:

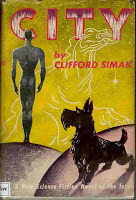

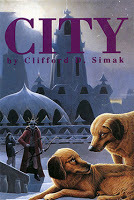

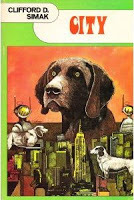

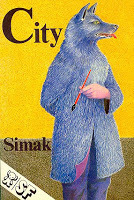

"These are the stories that the Dogs tell when the fires burn high and the wind is from the north. Then each family circle gathers at the hearthstone and the pups sit silently and listen and when the story's done they ask many questions:In the publishing world, it's a fix-up novel, a book cobbled from shorter pieces published previously, something very common in the science fiction genre where the market for short stories was huge while the novel market was smaller than small, which is how such classic works as Asimov's Foundation series, Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, and many of A.E. Van Vogt's novels came about. The first story ("City") was published in the May 1944 issue of Astounding Science Fiction and tells of the decentralization of society and the abandonment of man's cities. Man's return to a pastoral life (this time because of the freedom brought by the use of unlimited energy generators) is a common theme in Simak's works, probably due to his rural Wisconsin upbringing, which would also account for his boundless love dogs; in City, they eventually become the dominant species, along with robots, but in most of Simak's novels there's usually a dog to be found tagging along somewhere. Dogs, robots and cities (or lack thereof) figure prominently in the covers of this well-loved book:

'What is Man?' they'll ask.

Or perhaps: 'What is a city?'

Or: 'What is a war?'"

Personally, I think the French went a bit far with the dog angle when they retitled the book Demain les chiens, which translates as Tomorrow the Dog, but the French are French and there's just nothing to be done about it. If you want to find a copy of this book online, it's pretty easy, or if you live near a used book store (an endangered species if there ever was one); but you can also get a hardcover edition through the Science Fiction Book Club, which should include a ninth story written by Simak in 1973, which tells what eventually happens to the faithful robot Jenkins and the final fate of the ant-dominated Earth fled by man, dog and robot alike. For the purist (you're always out there somewhere, aren't you?), the original 1952 Gnome Press edition is usually available somewhere on AbeBooks or EBay.

Personally, I think the French went a bit far with the dog angle when they retitled the book Demain les chiens, which translates as Tomorrow the Dog, but the French are French and there's just nothing to be done about it. If you want to find a copy of this book online, it's pretty easy, or if you live near a used book store (an endangered species if there ever was one); but you can also get a hardcover edition through the Science Fiction Book Club, which should include a ninth story written by Simak in 1973, which tells what eventually happens to the faithful robot Jenkins and the final fate of the ant-dominated Earth fled by man, dog and robot alike. For the purist (you're always out there somewhere, aren't you?), the original 1952 Gnome Press edition is usually available somewhere on AbeBooks or EBay.All told, Clifford Simak wrote about thirty novels, along with numerous short story collections, but City is where I would advise the new reader to start. In it we see humanity and technology through Simak's pastoral eyes, and find robots and dogs who are better than the humans they serve. We also encounter such common Simak themes as souls, alternate timestreams, and pantropy. And we see why both editors and readers often termed Simak's human protagonists as "losers," men who usually muddled their way to success, and if they fell in love along the way it was as much accidental as incidental. "I like losers," Clifford Simak wrote, and he never abandoned his use of the lovable losers with whom we could all identify, no more than he did his beloved robots and dogs.

If you enjoyed this blog-post please feel free to share it with your friends using one of the social network buttons below. Thanks for investing your time, and for sharing.

Published on October 13, 2012 14:10

October 8, 2012

60 (yes, 60) Years of Bond

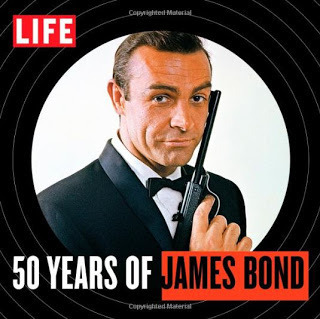

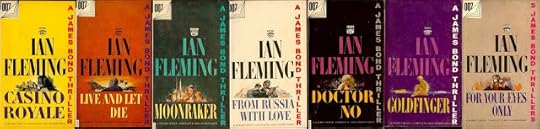

Oh my, all the hype and hoopla about 2012 being the semicentennial or golden jubilee anniversary of James Bond, Agent 007 with a license to kill and thrill in defense of the British Realm. Life Magazine has even risen from dormancy to publish a special issue dedicated to the man with the Walther PPK and all those tricky cars; if you're a fan, I greatly recommend the Life effort despite the hefty cover price and the error made in You Only Live Twice: the editors claim Bond did not drive any vehicle in the film when, of course, he piloted a small one-man helicopter ("Little Nellie"), brought to Japan by her Uncle Q. All the hustle-bustle about the 50th Anniversary is to spark more interest in the latest Bond film, Skyfall. The problem is, this is not the 50th anniversary, but the 60th, the diamond jubilee, or, more appropriately, the sexagennial. Yes, Commander James Bond may have first graced the silver screen in 1962 when Slyvia Trench became the first Bond Girl (sorry, Honey Ryder comes after her) in Dr No, but Mr Bond was first released on a dangerous Cold War world in Casino Royale, written in 1952 and published the following year. It may surprise those who know James Bond only from the great (and some not so great) films, but Bond made ten book appearances before the first film, and his father was Ian Fleming (1908-1964) writer and real-life WW2 spy.

Oh my, all the hype and hoopla about 2012 being the semicentennial or golden jubilee anniversary of James Bond, Agent 007 with a license to kill and thrill in defense of the British Realm. Life Magazine has even risen from dormancy to publish a special issue dedicated to the man with the Walther PPK and all those tricky cars; if you're a fan, I greatly recommend the Life effort despite the hefty cover price and the error made in You Only Live Twice: the editors claim Bond did not drive any vehicle in the film when, of course, he piloted a small one-man helicopter ("Little Nellie"), brought to Japan by her Uncle Q. All the hustle-bustle about the 50th Anniversary is to spark more interest in the latest Bond film, Skyfall. The problem is, this is not the 50th anniversary, but the 60th, the diamond jubilee, or, more appropriately, the sexagennial. Yes, Commander James Bond may have first graced the silver screen in 1962 when Slyvia Trench became the first Bond Girl (sorry, Honey Ryder comes after her) in Dr No, but Mr Bond was first released on a dangerous Cold War world in Casino Royale, written in 1952 and published the following year. It may surprise those who know James Bond only from the great (and some not so great) films, but Bond made ten book appearances before the first film, and his father was Ian Fleming (1908-1964) writer and real-life WW2 spy.

American readers in the 1950s and 1960s encountered the exploits of James Bond in Signet editions, and those are the editions (except for some British numbers) I have in my own collection. They were published in such great numbers that they are still easily found both on and off line. It's probably more of an emotional/nostalgic connection but I prefer these over the later editions, especially those reissued as a film tie-in. James Bond was for me a literary character before I saw my first Bond film, and that's what I think of him as first, even though the fellows who strut across the screens are the ones who will have the enduring public legacy. My hope as a bibliophile, of course, is that the films will lead people to read the books, just as Guy Ritchie's frenetic Sherlock Holmes films led some people to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In addition to Fleming's own books, however, there are some other related tomes well worth tracking down.

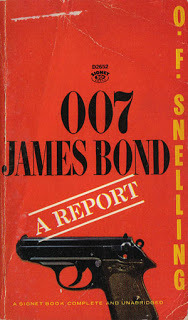

First and foremost in your ancillary James Bond library should be O.F. Snelling's 007 James Bond: A Report, published in 1964. Snelling was a Bond fan from the very beginning, with the publication of that "remarkable book" Casino Royale in 1953; additionally, he was an expert on antiquarian books and worked for several prestigious auction houses including Sotheby's. It's natural, then, that his biography concentrates on Bond as revealed in Fleming's tales. As Snelling wrote the book, he knew he was in a race with Kingsley Amis, who was writing his own critical analysis of the Bond novels; beating Amis into print assured the bestselling status of his own book (hitting the stands at the very apex of Bond fever) but it meant he also beat the publication of You Only Live Twice, which contained an obituary (rather premature, as it turned out) for James Bond, issued by MI6 in an effort to set the record straight about certain "high-flown and romanticized caricatures of episodes in the career of an outstanding public servant." He did not rewrite the paperback edition of the book, but did include footnotes here and there. You Only Live Twice is a good place to stop with Bond, since the true identity of the author of The Man With the Golden Gun (1965) is muddled at best, and the less said about Octopussy & The Living Daylights (1966) the better.

First and foremost in your ancillary James Bond library should be O.F. Snelling's 007 James Bond: A Report, published in 1964. Snelling was a Bond fan from the very beginning, with the publication of that "remarkable book" Casino Royale in 1953; additionally, he was an expert on antiquarian books and worked for several prestigious auction houses including Sotheby's. It's natural, then, that his biography concentrates on Bond as revealed in Fleming's tales. As Snelling wrote the book, he knew he was in a race with Kingsley Amis, who was writing his own critical analysis of the Bond novels; beating Amis into print assured the bestselling status of his own book (hitting the stands at the very apex of Bond fever) but it meant he also beat the publication of You Only Live Twice, which contained an obituary (rather premature, as it turned out) for James Bond, issued by MI6 in an effort to set the record straight about certain "high-flown and romanticized caricatures of episodes in the career of an outstanding public servant." He did not rewrite the paperback edition of the book, but did include footnotes here and there. You Only Live Twice is a good place to stop with Bond, since the true identity of the author of The Man With the Golden Gun (1965) is muddled at best, and the less said about Octopussy & The Living Daylights (1966) the better.

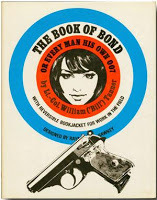

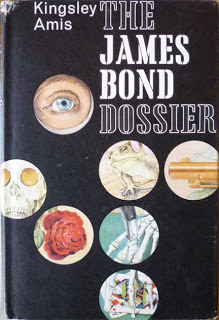

The aforementioned Kingsley Amis was a good friend of Ian Fleming and wrote three books in the vein that of importance. The first, The James Bond Dossier (1965), was his own take on the novels, and although the essay from which the book grew was written somewhat earlier, it was Snelling's book that reached the public first, taking away a bit of the thunder which this book deserves. Amis' own status as a literary giant and a Renaissance man gives his book a depth lacked by Snelling's, as well as a hefty dose of dry British humor. The second is The Book of Bond (Every Man His Own 007), published the same year as Dossier and is a foray more solidly into humor, instructing men how to be like James Bond, using extensive quotes from the books as illustrations; the first edition of this British book featured a slipcase entitled The Bible to be Read as Literature, presumable so agents of SMERSH or SPECTER would not be able to spot their wannabe adversary. The third book to consider is Colonel Sun, first of the non-Fleming James Bond adventures, which Amis wrote under the pen name Robert Markham. Bond, in tracking down the kidnappers of M, foils a plot by Communist China to create an international incident. Not Fleming, but a good novel nonetheless, and much more readable than many of the many novels that followed from other hands.

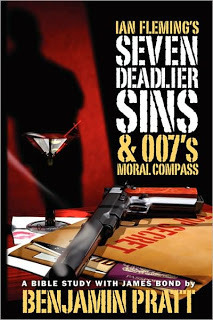

Among the more odd oddities of books about Ian Fleming's literary creation is one written by Benjamin Pratt, a retired pastor of the United Methodist Church. In Ian Fleming's Seven Deadlier Sins & 007's Moral Compass: A Bible Study With James Bond Pratt sees Fleming's tales as modern parables. In seven lessons, complete with biblical references and discussion questions, Pratt examines Fleming's complex spiritual allegories. As Pratt said in an interview with CommanderBond.Net: "...at the core, each Bond tale reflects choices between moral courage and moral cowardice. This is not only reflected in the characters James Bond pursues, but in Bond, as well. When he is true to his duty and mission, his choices are morally courageous. But, like most of us, he gets world-weary (accidie) and he fails to stay true to course. He becomes self-righteous, hypocritical, snobbish, and cruel or lust driven, his most infamous moral struggle. He is constantly battling the inner spiritual and moral war, as well as the war with the deadly demons he pursues." Perhaps the oddest thing about this book is that it actually succeeds in its purpose, and will be of interest to both truth seeker and thrill seeker.

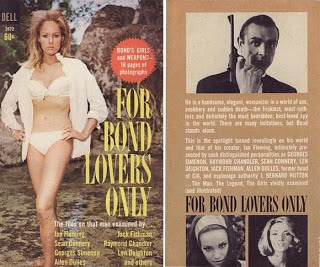

Among the more odd oddities of books about Ian Fleming's literary creation is one written by Benjamin Pratt, a retired pastor of the United Methodist Church. In Ian Fleming's Seven Deadlier Sins & 007's Moral Compass: A Bible Study With James Bond Pratt sees Fleming's tales as modern parables. In seven lessons, complete with biblical references and discussion questions, Pratt examines Fleming's complex spiritual allegories. As Pratt said in an interview with CommanderBond.Net: "...at the core, each Bond tale reflects choices between moral courage and moral cowardice. This is not only reflected in the characters James Bond pursues, but in Bond, as well. When he is true to his duty and mission, his choices are morally courageous. But, like most of us, he gets world-weary (accidie) and he fails to stay true to course. He becomes self-righteous, hypocritical, snobbish, and cruel or lust driven, his most infamous moral struggle. He is constantly battling the inner spiritual and moral war, as well as the war with the deadly demons he pursues." Perhaps the oddest thing about this book is that it actually succeeds in its purpose, and will be of interest to both truth seeker and thrill seeker. Although there are numerous other books about James Bond (and most of them dwell on nothing but the films), there is just one other book to suggest for your collection of vintage Bond. For Bond Lovers Only (1965), was compiled and edited by Sheldon Lane. Although 19 of the 29 photos in the center of the book are great looking girls from the films (the other photos are of even better looking guns), the real emphasis is on the Bond books, the Bond character, and on Fleming as a writer. Most of the selections have no date or place of original publication, but I think they were either magazine or newspaper features. While the stars of some of the writers have slipped into unfortunate obscurity, many still have prominence today in the fields of spy and crime writing -- in an interview, Raymond Chandler tells what he thinks of Fleming as a writer and James Bond as a tough guy ("a little too tough"); French writer Georges Simenon discusses "the thriller business" in general and Fleming in particular; Jack Fishman interviews Fleming about who Bond is and where he came from; former Communist and espionage expert Bernard Hutton recalls how Fleming interviewed him for an article about spies; and former CIA Director Allen Dulles (The Craft of Intelligence) tells of the Ian Fleming he knew and how he was given his first James Bond book (From Russia With Love), a book he liked not just for its writing but because he lived in Constantinople after the Great War, by Jacqueline Kennedy. More than any of the other books, this one is like sitting down with a few old friends and gabbing about a mutual love.

Although there are numerous other books about James Bond (and most of them dwell on nothing but the films), there is just one other book to suggest for your collection of vintage Bond. For Bond Lovers Only (1965), was compiled and edited by Sheldon Lane. Although 19 of the 29 photos in the center of the book are great looking girls from the films (the other photos are of even better looking guns), the real emphasis is on the Bond books, the Bond character, and on Fleming as a writer. Most of the selections have no date or place of original publication, but I think they were either magazine or newspaper features. While the stars of some of the writers have slipped into unfortunate obscurity, many still have prominence today in the fields of spy and crime writing -- in an interview, Raymond Chandler tells what he thinks of Fleming as a writer and James Bond as a tough guy ("a little too tough"); French writer Georges Simenon discusses "the thriller business" in general and Fleming in particular; Jack Fishman interviews Fleming about who Bond is and where he came from; former Communist and espionage expert Bernard Hutton recalls how Fleming interviewed him for an article about spies; and former CIA Director Allen Dulles (The Craft of Intelligence) tells of the Ian Fleming he knew and how he was given his first James Bond book (From Russia With Love), a book he liked not just for its writing but because he lived in Constantinople after the Great War, by Jacqueline Kennedy. More than any of the other books, this one is like sitting down with a few old friends and gabbing about a mutual love.

I don't discount the importance and popularity of the films, and I fully realize that if Bond is around in other 40 years (joining Sherlock Holmes in the Centennial Hall of Fame maintained in the Diogenes Club) it will be because of the influence of the films. Still, I have hopes that people will from time to time return to the source waters of the character, and feel refreshed and enlightened for having done so. And so...

Published on October 08, 2012 16:56

September 19, 2012

Collaborating With Conan Doyle

If the fiction writer is viewed as an artisan with the consumer end-products being short stories and novels, then the raw materials are imagination, research and life experience. So, if I write, for example, a murder mystery set in the 1960s, the characters might come from people I knew or be created broadcloth to advance the story, and the plot might stem from some social conflict of the times, such as anti-war protests or the counter culture, or revolve around the Big Three (sex, greed or revenge) with the milieu of the 1960s chosen simply because men still wore hats and women gloves.

When you venture into an already established literary universe, however, the "raw materials" of the story are provided and limitations are in place. A writer for DC Comics once told me that there were many things he would have liked to do with the Superman character, many facets of his personality that he would have liked to explore, but no matter what you want to do you always have to remember "you are a guest in someone else's playground, playing with some other kid's toys; when you move on, you leave the toys behind for the next kid."

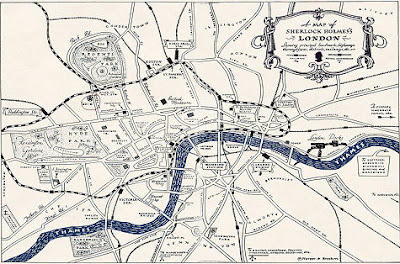

You you can plot a free-for-all in H.P. Lovecraft's realm (as long as you kill your characters or have them go stark barking mad) and you'll be fine, but when you enter the universe of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, there are Rules. After all, we're talking about Sherlock Holmes, the icon of icons, the most famous fictional character in the world, and every single mannerism, every little utterance, every little nuance has been the subject of intense study and several monographs by people who live on Baker Street, breakfast with Holmes, and likely have London fog in their lungs and a seven-percent solution coursing through their veins. Make a grievous error with the characters of Holmes or Watson (or even a lesser light like Lestrade), or erroneously describe a gasogene or tantalus, they will not only heap scorn on you, you might receive an envelope with five orange pips in it.

In other Sherlock Holmes books I've written, I introduced the character into original plots, though against recognizable backgrounds -- an elderly Holmes encountering HP Lovecraft in the 1920s, Holmes in a pure adventure story with Professor Challenger, Holmes as a consulting detective in the Dreamlands with Nikola Tesla as his Watson. In these and others, the character was established but the plot was entirely original.

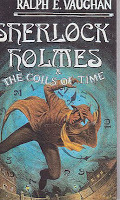

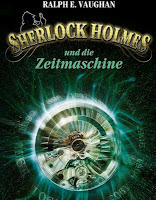

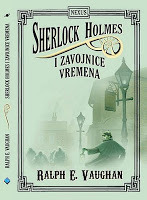

When I wrote

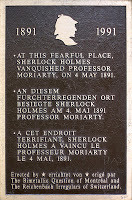

Sherlock Holmes and the Coils of Time

, however, I had to work around an already established plot, the one Conan Doyle used in The Adventure of the Empty House, which returned Sherlock Holmes to life in 1894, after his apparent death at Reichenbach Falls on 4 May 1891. To refresh your memory, Holmes returns to London and reveals himself to his shocked biographer, but his life is in danger from Colonel Sebastian Moran, dead Moriarty's former associate and the "second most dangerous man in London." Through a ruse involving Mrs Hudson moving a bust of Holmes behind a window shade, Moran is captured in the empty house across from from 221B Baker Street, ending the threat and bringing the bounder to justice for the murder of the Right Honourable Ronald Adair (actually, he apparently escapes the hangman's noose he is mentioned as still living in His Last Bow).

When I wrote

Sherlock Holmes and the Coils of Time

, however, I had to work around an already established plot, the one Conan Doyle used in The Adventure of the Empty House, which returned Sherlock Holmes to life in 1894, after his apparent death at Reichenbach Falls on 4 May 1891. To refresh your memory, Holmes returns to London and reveals himself to his shocked biographer, but his life is in danger from Colonel Sebastian Moran, dead Moriarty's former associate and the "second most dangerous man in London." Through a ruse involving Mrs Hudson moving a bust of Holmes behind a window shade, Moran is captured in the empty house across from from 221B Baker Street, ending the threat and bringing the bounder to justice for the murder of the Right Honourable Ronald Adair (actually, he apparently escapes the hangman's noose he is mentioned as still living in His Last Bow). As The Doctor will tell you, there are points in time where you jimmy about, go on a lark, muck around, trample all over the sands of history without changing the warp or woof of things; and there are points in time which cannot be changed, no matter what -- Pompeii will always be destroyed by Vesuvius, the Great Fire will always sweep through London, and Rose Tyler's Dad will always die in a traffic accident on 7 November 1987. And it's "the burden of a Time Lord" to know what points in time are fixed and which are in flux. Well, I may not be a Time Lord, I may not be a madman with a Blue Box (I would like to have a Blue Box), but I surely know that Holmes' return to London on 5 April 1894, and all that events that occurred on that long-ago Thursday, is a fixed point in time if there ever was one. I could not change one single event, as recorded by Conan Doyle.

As The Doctor will tell you, there are points in time where you jimmy about, go on a lark, muck around, trample all over the sands of history without changing the warp or woof of things; and there are points in time which cannot be changed, no matter what -- Pompeii will always be destroyed by Vesuvius, the Great Fire will always sweep through London, and Rose Tyler's Dad will always die in a traffic accident on 7 November 1987. And it's "the burden of a Time Lord" to know what points in time are fixed and which are in flux. Well, I may not be a Time Lord, I may not be a madman with a Blue Box (I would like to have a Blue Box), but I surely know that Holmes' return to London on 5 April 1894, and all that events that occurred on that long-ago Thursday, is a fixed point in time if there ever was one. I could not change one single event, as recorded by Conan Doyle.In Sherlock Holmes and the Coils of Time, I had my own original plot of Morlocks in London, vanishings in the East End, and H.G. Wells' Time Traveller. I also had in mind what Philip Jose Farmer did in The Other Log of Phileas Fogg , in which he took the events and characters of Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days, and made them set-pieces in a conflict between two adversarial alien races, the Erindani and the Capellans. In my story, Holmes did not return to London because of Adair's murder, but because of a letter sent him by a future version of himself. For awhile there are two Sherlock Holmeses coming and going from 221B Baker Street, which helps Conan Doyle explain why Moran thought Holmes was there when he was not -- afterwards Mrs Hudson is hurried on her way (and Watson too) when she asks about the soft moving sounds in Holmes' locked bedroom. After the events of the Empty House are played out, Holmes goes on the case for which he was really recalled to London.

Though the entirety of Sherlock Holmes and the Coils of Time takes place on Thursday, 5 April 1894, it also ranges from the beginning of time to the end of it. Although it was fun "collaborating" with Conan Doyle on a story, it was very difficult being original while remaining faithful to the source material. My favorite moment in the story, however, is my own -- as Sherlock Holmes and Inspector Kent pass down Baker Street in a Hansom, bound for the East End and the and the year A.D. 802701, Holmes gazes up and sees a familiar figure in the window watching him, knowing that, in time, he will be the one gazing down from the window of 221B at a Hansom passing in the night.

The Time Machine

The Time MachineClassics Illustrated, 1951

Published on September 19, 2012 09:46

September 11, 2012

Books of Maybe Maps

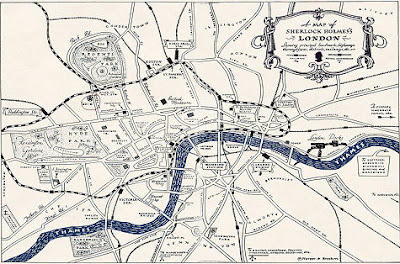

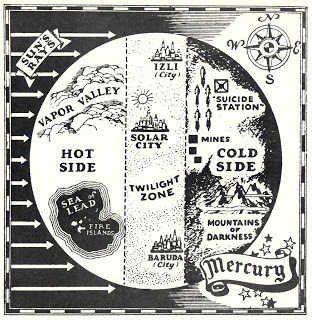

I like to say I have a fondness for maps, but I heartily disagree with those who claim my relationship with products of the cartographer's art is more like an addiction. After all, my "fondness" for maps and charts of all kinds does not at all approach the feelings I have for books: then "addiction" might be an appropriate word. When we come to atlases, however, we move into dangerous territory, and over the years I have bought every affordable atlas I've come across, the older the better, and let's not even go into my collection of London guidebooks; but I'm at my most vulnerable when I come across atlases containing maps of worlds that never were, maps that chart the geography of the mind and the imagination. Two atlases I bought back in the early 80s still afford me hours of charted pleasure, nearly as much the the literary milieu from which the maps were derived.

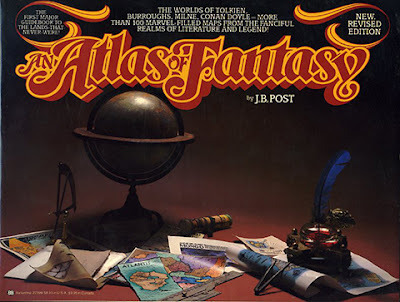

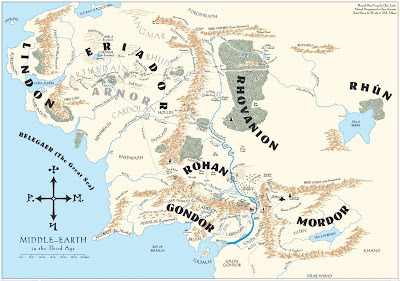

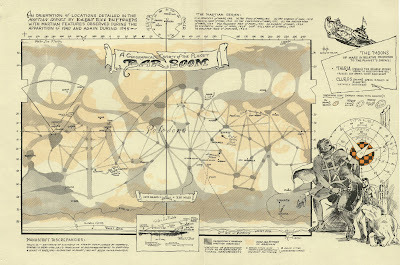

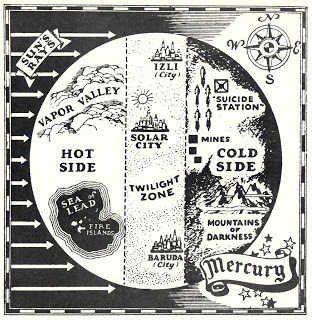

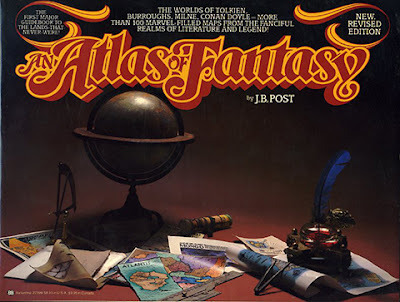

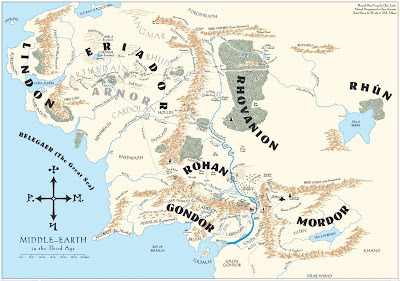

An Atlas of Fantasy by J.B. Post was first published in 1973 by Mirage Press but because the publisher was a very small press (founded by writer Jack Chalker) dedicated to nonfiction and bibliographic works of a fannish nature, Atlas did not receive the distribution or recognition it deserved. Ballantine Books issued a revised mass market edition in 1979, for which they deleted 11 maps, but added 14, and it is this edition, its cover depicting a map collector's fantasy, with which most people are familiar. The emphasis is on science fiction and fantasy, so we get maps of various avatars of Mars and Venus, Middle Earth, Narnia and the imaginary landscapes envisioned by H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith.

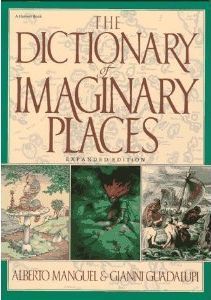

In The Dictionary of Imaginary Places, however, the emphasis is on terrestrial realm, as science fiction maps of worlds beyond the sky are specifically excluded, as are maps of Heaven, Hell, the world of the future, and real places festooned with literary traditions. Despite all that is left out, the inclusions make for a very thick book. Published in 1980 (revised in 1987 & 1999), The Dictionary of Imaginary Places by Alberto Mangual and Gianni Guadalupi delves into almost all fantastic literature, published from the Middle Ages to the middle of the 20th Century, where some lost, forgotten or imagined realm on Earth is mentioned, most of it obscure to even the most widely read fan. What raises this book from its titular claim of Dictionary to Atlas are the tremendous number of maps, both original and those prepared for the volume.

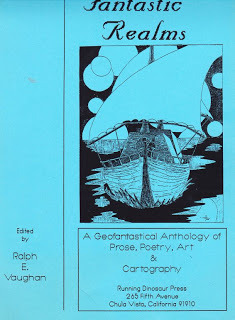

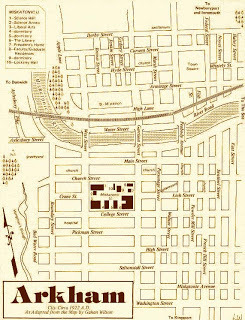

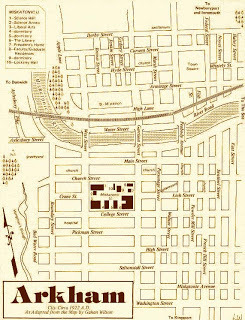

Both these books were very in mind when in 1992, under my Running Dinosaur Press imprint, I edited and published a 67-page booklet entitled Fantastic Realms -- A Geofantastical Anthology of Prose, Poetry Art & Cartography. When I sent out a call for submissions and sent guidelines to interested writers I made it very clear that all stories and poems had to possess a strong "sense of place" if they had any hope of being published here; and I gave preference to stories that were "chartable," in that they told a fascinating tale while at the same time gave me enough information to draw a map. The response was good and I received about two dozen works worthy of publication; additionally, I was able to create eight maps, which I included in a section entitled "Cartigraphia Fantastica," attended by a short essay on maps in general, fantasy maps in particular. Several maps were derived from stories in the booklet, some were from fantasy traditions (such as a map of Osirian Africa and a kinetic mapview of Lemuria), but the one which I enjoyed most drawing and bringing to fandom's attention was a map of the city of Hampdon ("the Arkham of he West...") which was based on the works of my dear friend Duane Rimel (1915-1996), and although he did not have a work in Fantastic Realms, I had in the 1980s republished his classic fiction and poetry in The Many Worlds of Duane Rimel and The Second Book of Rimel, as well as an illustrated version of his sonnet sequence Dreams of Yith. The booklet was well received and sold out quickly.

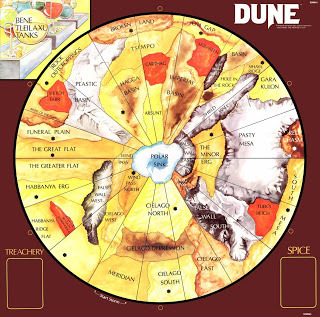

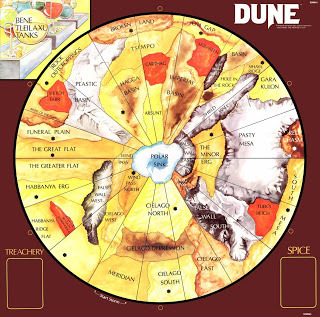

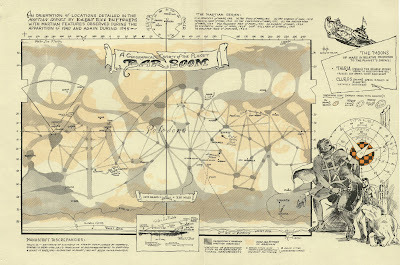

Maps have always gone over well with readers of science fiction and fantasy. In addition to the two mass market books mentioned, there have been other books dedicated to a single author's vision, in which maps were well represented. It's hard to think of Middle Earth, Barsoom or Dune without thinking of maps. Indeed, there are probably more people who could point out Helium, The Shire or the Imperial Basin on a map than could find Colombia, Iran or Lapland...I just can't figure out whether that is good or bad.

from the "Dune" boardgame

from the "Dune" boardgame

Middle Earth from lotr net

Middle Earth from lotr net

based on Wilson

based on Wilson

from ERB

from ERB

based on Baring-Gould

based on Baring-Gould

from Captain Future

from Captain Future

from Clark Ashton Smith

from Clark Ashton Smith

An Atlas of Fantasy by J.B. Post was first published in 1973 by Mirage Press but because the publisher was a very small press (founded by writer Jack Chalker) dedicated to nonfiction and bibliographic works of a fannish nature, Atlas did not receive the distribution or recognition it deserved. Ballantine Books issued a revised mass market edition in 1979, for which they deleted 11 maps, but added 14, and it is this edition, its cover depicting a map collector's fantasy, with which most people are familiar. The emphasis is on science fiction and fantasy, so we get maps of various avatars of Mars and Venus, Middle Earth, Narnia and the imaginary landscapes envisioned by H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith.

In The Dictionary of Imaginary Places, however, the emphasis is on terrestrial realm, as science fiction maps of worlds beyond the sky are specifically excluded, as are maps of Heaven, Hell, the world of the future, and real places festooned with literary traditions. Despite all that is left out, the inclusions make for a very thick book. Published in 1980 (revised in 1987 & 1999), The Dictionary of Imaginary Places by Alberto Mangual and Gianni Guadalupi delves into almost all fantastic literature, published from the Middle Ages to the middle of the 20th Century, where some lost, forgotten or imagined realm on Earth is mentioned, most of it obscure to even the most widely read fan. What raises this book from its titular claim of Dictionary to Atlas are the tremendous number of maps, both original and those prepared for the volume.

Both these books were very in mind when in 1992, under my Running Dinosaur Press imprint, I edited and published a 67-page booklet entitled Fantastic Realms -- A Geofantastical Anthology of Prose, Poetry Art & Cartography. When I sent out a call for submissions and sent guidelines to interested writers I made it very clear that all stories and poems had to possess a strong "sense of place" if they had any hope of being published here; and I gave preference to stories that were "chartable," in that they told a fascinating tale while at the same time gave me enough information to draw a map. The response was good and I received about two dozen works worthy of publication; additionally, I was able to create eight maps, which I included in a section entitled "Cartigraphia Fantastica," attended by a short essay on maps in general, fantasy maps in particular. Several maps were derived from stories in the booklet, some were from fantasy traditions (such as a map of Osirian Africa and a kinetic mapview of Lemuria), but the one which I enjoyed most drawing and bringing to fandom's attention was a map of the city of Hampdon ("the Arkham of he West...") which was based on the works of my dear friend Duane Rimel (1915-1996), and although he did not have a work in Fantastic Realms, I had in the 1980s republished his classic fiction and poetry in The Many Worlds of Duane Rimel and The Second Book of Rimel, as well as an illustrated version of his sonnet sequence Dreams of Yith. The booklet was well received and sold out quickly.

Maps have always gone over well with readers of science fiction and fantasy. In addition to the two mass market books mentioned, there have been other books dedicated to a single author's vision, in which maps were well represented. It's hard to think of Middle Earth, Barsoom or Dune without thinking of maps. Indeed, there are probably more people who could point out Helium, The Shire or the Imperial Basin on a map than could find Colombia, Iran or Lapland...I just can't figure out whether that is good or bad.

from the "Dune" boardgame

from the "Dune" boardgame Middle Earth from lotr net

Middle Earth from lotr net based on Wilson

based on Wilson from ERB

from ERB based on Baring-Gould

based on Baring-Gould from Captain Future

from Captain Future from Clark Ashton Smith

from Clark Ashton Smith

Published on September 11, 2012 18:29