Sage Cohen's Blog, page 2

June 5, 2019

The incantatory consolation of language

When there is nothing to be done, there is language. More specifically, says poet Gregory Orr, we can turn to “the incantatory consolation of language” to help us navigate our deepest darknesses.

In his expansive conversation with On Being’s Krista Tippett about Shaping Grief with Language, Orr speaks about how lyric poetry was his path of transformation through a tragic hunting accident in which he accidentally shot and killed his younger brother at the age of 12.

He says, “…What made me a poet the moment…I wrote my first terrible poem, was the discovery that language in poetry is magical language…It summons a world into being.” By dramatizing both our experience of disorder and our need for order, says Orr, reading and writing poetry helps transmute the unbearable to our own personal liturgy, through which we may ultimately find our way.

I believe we can make even the most implausible crossings in poems. Which is why I created the Poem Medicine ritual. As we gathered in an intimate circle last month to shine a collective light into our unspoken places, we wrote ourselves through fear, pain, and regret toward greater resolution, hope, and healing.

You can, too.

To be alive: not just the carcass

But the spark.

That’s crudely put, but …

If we’re not supposed to dance,

Why all this music?”

— Gregory Orr

Poems help sustain the spark that no wound can snuff out. They keep our ear attuned to the music and our bodies awake to the dance.

What poem/s help you navigate your most complicated places? Could it be time to read or write something new that welcomes you more deeply into the alchemies of loss and learning?

The post The incantatory consolation of language appeared first on Sage Cohen.

April 14, 2019

Resilience poetics as life practice

Do you ever write something down, reread it, and discover something about yourself that’s been there all along?

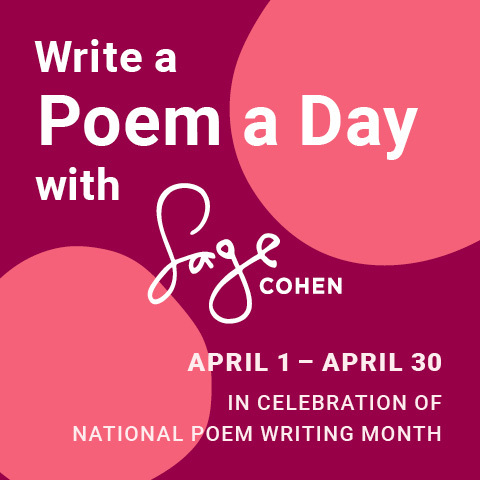

This happened to me when I revisited today’s lesson in my Write a Poem a Day class featuring Jack Gilbert’s Failing and Flying, one of my favorite poems of all time. Like Gilbert, I believe anything worth doing is worth doing badly. And that’s why I’m a champion of daily poetry practice.

When we do something every day, we learn to relax. The work we produce is not so precious. It’s just the day’s work. And tomorrow, there will be more. And then more after that. When the focus is on practice and not product, we are likelier to take bigger risks, discover bigger ideas, and stumble into unprecedented territory. When we are consistently surprising and delighting ourselves in this way, we’re far likelier to keep writing—and ultimately, improving.

That’s why I hold all writing we do as practice. Every word we commit to the page takes us that much further into ourselves, our craft, and our evolution as a writer.

But what I didn’t quite understand until I saw it written into my lesson is the turf I occupy as a writer and teacher. The truth is, I don’t care that much whether anyone writes a good or great or publishable poem—or any other kind of writing. What I do care about almost as much as I care about breathing is what I’m calling “resilience poetics”. I want to write and read and share and invite poems that teach us how to make loss generative, medicinal, and sometimes even triumphant.

I want poems that instruct me how to live.

I’ve been obsessed with poems for 30+ years, and it finally clicked that this is what I’ve been after: writing and reading myself through to resilience. And inviting others to do the same.

Along the way, I’ve noticed that the better my poems get, the better my life gets. And vice versa. The two are irrevocably entwined. Discovery, healing, and craft coalesce as language becomes its own alchemical salve for all that we attend to.

What do you want from your writing? What do you want for your life? And how might the two begin (or continue) to mingle? I’d love to hear in the comments below!

Let’s get resilient together!

Poem Medicine: A Ritual of Hope and Healing meets virtually (online) on Saturday, May 11 from 10 a.m. to noon PT. (If this time doesn’t work for you, I’ll be offering another ritual in June!)

The Crucible of You: Write Yourself from Hurt to Healing , a live workshop from August 31 to September 1 at Sitka Center for Art and Ecology.

The 30/30 momentum continues in May! $50 gets a poem written for you.

In the month of May, I’ll be participating in Tupelo Press 30/30 project – a kind of poetry writing marathon like the one I’m leading now! Except this 30/30 project is a fundraiser for this press that I cherish. I’ll be writing a poem / day in the company of some amazing poets. All of our work will be shared daily on the Tupelo Press website. You’ll see the underbelly of poems getting written fast, as practice not product. I’ll share that link when the time comes! You can sponsor me for any amount! Contribute $50 or more and I’ll write an ode just for you (or for anyone you’d like)!

The post Resilience poetics as life practice appeared first on Sage Cohen.

March 12, 2019

You can’t get it published if you don’t send it out

At a recent writer’s conference, I was talking to a poet who mentioned wanting to be published for the first time.

“How many poems have you sent out to literary journals so far?” I asked.

“None,” he replied.

“How many of the poems you never submitted do you think might get published?” I countered.

He was stumped for a minute, and then we both laughed.

Recognize yourself here?

We can’t predict what will happen when we take the risk to send out our work for publication. But we can be 100% sure that we won’t be published if we never try.

I’m not saying it’s the right time for you to be sending out your work. Only you know that. What I am saying is that if you’re ready to have your writing in the world and you’re not taking the steps toward that path, it may be time to reconsider.

Need a jolt of courage? I’ve got you covered!

Need a clear plan for how to make publication a priority in your life? This simple worksheet has helped hundreds of poets and writers like you simplify and amplify their work.

Want to establish or enhance your writing practice so you have more poems to submit? Let’s do it together in April!

Because I tend to prioritize writing over publishing, finished work can accumulate for years. In December, I made a commitment to start sharing my stockpile of poems and essays that have never traveled beyond my own computer screen.

I researched publications, responded to a few invitations from editors, and sent out several batches of work. In February, I had four poems accepted for publication (thank you, Kosmos Quarterly and The Midnight Oil!) along with a number of rejections.

Because I made it a priority to send them out, four more of my poems are entering the world.

Because I’ve scheduled a bi-weekly “submissions” session for the rest of 2019, I know I can count on myself to sustain my momentum of seeking out communion with readers.

Plus, sending my work out keeps me engaged in revising and refining. As if there were someone out there counting on me to share finished work that is worthy of them.

This is how the quest to publish becomes a virtuous circle.

Write, revise, submit, repeat. Over time, this process refines us and our work to what is most essential. It gives us a better understanding of our place in the literary community. Most importantly, we learn we can count on ourselves to do what matters—even when it’s scary, even when we can count on rejection and discouragement—and be better for it.

The post You can’t get it published if you don’t send it out appeared first on Sage Cohen.

March 5, 2019

How poetry saved my apartment building

I spent my late 20’s in a third-floor walk-up on Dolores Street in San Francisco.

My desk (from which I conducted my newborn copywriting business) looked out over a high school football field from which the secondary sights and sounds of teen spirit mingled with my work and my life.

Apartment living compresses community to a 360-degree sensory merger. The choices we make (sounds, smells, cats in the halls spraying everyone’s front doors,) often have an immediate impact on our neighbors.

Most of us were in our 20s and 30s, drastically hip or artistic or professionally successful, trying out identities and ways of being and living. Directly above me lived a man I’d never met but had heard much about from my neighbors.

I was told this man had been living in the building since it opened in the 1940s—which would have put him at least in his early 80’s. And that he’d been stockpiling newspapers and magazines since that time, making his home barely penetrable. (Hoarder, they whispered.)

Also, I was told to be on red alert for groping in the stairwell.

Already about fifteen years deep into my poetry practice, a part of my brain was permanently designated as “witness”. Secretly studying other people, then writing down what I saw, was the practice through which I tried to make sense of my own life. This invisible neighbor of mine sounded more like a character in a short story than anyone I’d ever experienced in person. It seemed strange that I’d never encountered him as I loped up and down three flights of stairs numerous times per day.

Seated at my desk one afternoon, brainstorming the elements of a communications campaign for a healthcare company’s new service, I began to notice a rhythmic sound that rose above the din of football practice.

My first diagnosis: drumming. I kept writing.

When the percussion repeated, I tried to locate the sound and make sense of it. If one of my neighbors was holding band practice in their apartment, this was going to be a problem. But the sound seemed to be coming from above, which didn’t make sense.

When the third chorus came from my ceiling, I saw it in a flash: the mystery man had fallen. He was knocking on the floor.

Maybe.

“Are you ok? Did you fall?” I yelled up at my ceiling, hands an improvised bullhorn around my mouth.

Nothing. Followed by more knocking.

I paced around for a minute, nervous system all amped up, uncertain of what to do next. I was fairly certain that I was catastrophizing. I’d seen enough of those, “Help, I’ve fallen, and I can’t get up!” ads to conjure an emergency that didn’t exist.

But when the knocking came again, I had to be sure. Leaping stairs two at a time, I arrived at his door panting and started pounding. Then shouting.

“Are you in there? Are you ok? I heard you knocking…Do you need help?”

No response came from inside. But a few neighbors came out to see what was going on and joined me at his apartment door, speculative and passive. No one had a key. We couldn’t find the building manager. I called 9-1-1.

When the strapping squad of firefighters broke down my neighbor’s door, they fought their way through a ceiling-high tunnel of paper to find a pan on the lit stove burning fish and a man on the floor who could not get up. If we hadn’t found him just then, they said, his apartment and our entire building would likely have gone up in flames.

Somehow, I never saw my neighbor or his apartment throughout the entire rescue. And he never returned to our building. I was told that he suffered a stroke. And, after the hospital, he went to a long-term care facility. Someone came and cleaned out his apartment, spreading rumors of finding naked photos of our mail carrier among the man’s possessions. The man I never knew whose life had overlapped mine in crisis remained a kind of fiction to me. One of my own San Francisco stories.

A few months later, it hit me: Poetry had saved this man’s life — along with the entire apartment building. It was my practice of tuning into what I might otherwise tune out that had brought the firemen to my neighbor’s door.

And though there were far less heroics involved (and no sculpted men in jumpsuits), I understood that my poetry practice has saved my own life, as well.

By creating a space of exploration between event and interpretation, poetry has slowed me down enough to discover that I get to decide what it all means—and this influences how it all feels. When I’ve fallen and I can’t get up, poetry has me curious about the history of the floorboards, the brittle fear of fish burning on the stove, and the muted mercies of newsprint. When neighbors and strangers knock down my doors, poetry is the kindness I seek in their eyes.

I’m so grateful the man lived. The building was spared. My home and my cats were safe, along with all of the other lives that mingled with mine back then. I’m so grateful that when there is nothing to be done, I can write. Which changes nothing—and also changes everything.

All this from being still and willing to listen.

===

Want to write 30 poems in 30 days—in great company? Join me in the Write a Poem a Day class! Every day in April, you’ll get prompts, tips, and inspiration for your daily poem practice. Plus, share poems, ideas, and feedback with a global community of poets in our private online classroom. Or, explore more ways I can support you in other upcoming events!

The post How poetry saved my apartment building appeared first on Sage Cohen.

February 8, 2019

Are you good at too many things?

When I was in graduate school studying poetry with the world-renowned poet Galway Kinnell, he said something to me that I’d like to say changed my life. But it didn’t.

“You know what the problem is with your poetry?” Galway asked, then answered before I could, “You’re good at too many things.”

It didn’t seem fair to blame my competence in life for whatever inadequacies he saw in my poems. And because I had no idea how to apply this insight, it has hung in the air for me like a Zen Buddhist koan ever since.

Admittedly, at the time I had five part-time jobs that amounted to more than two full-time jobs, on top of graduate school. I was teaching poetry to undergrads, running the NYU Creative Writing Department’s reading series, running the volunteer teaching program at Goldwater Hospital (and also teaching there), and in parallel working as Kinnell’s personal assistant.

At this time in my life, I saw taking care of everything and everyone else as a kind of penance I paid for my right to exist. And I was doing a mighty fine job of it, I might add. I was also quite proud that I had a range of marketable life skills beyond writing poems that allowed me to provide well for myself.

20 years later, my life looked about the same, with the volume of responsibility and pressure about 2.5 times greater than what could safely make its way through the hose. There was too much of everything: work, pets, stuff, mothering alone, handling a household alone, volunteer commitments, friends in need, colleagues in need, deadlines, pressure.

I wasn’t sleeping. I wasn’t leaving the house. There was little pleasure in my life.

One of my most incomprehensible excesses was my yard. Having lived my entire adult life in urban apartments, I did not know how to cultivate the earth. So, I took a food gardening class. There I learned that all of the baby carrot starts weren’t going to make it—but that’s ok, no one expects them to.

A time comes when a certain number of carrots must be pulled from the earth so there is enough room for the rest to thrive. Too many carrots crowding each other as they grow amounts to no edible carrots.

My lifelong stampede of more and better was stopped in its tracks with this concept of pruning.

I finally understood what Galway was once trying to tell me. A life of too many things (even wonderful things) starves the poem, the carrot, the tree branch. Cutting back is the path to thriving.

My life, my poetry, and my heart all needed more of me than I had ever been willing to give. I set out to learn how to give it.

As I made room in my garden beds for the vegetables to realize their full potential, I looked for ways to prune my life practices, as well. I budgeted, tracked, and conserved money. I whittled my clothing to a capsule wardrobe. I set a limit to the number of hours I could volunteer weekly. I honored my office hours and left the phone home during my forest walks. I cleared all work devices and temptations from the spaces where I played with my son.

Slowly, eventually, poems rose up out of the clearing ground. And even those needed to be pruned. Six possible writing projects were distilled to a single, definite writing project.

As I became more intentional, aligned, simple, and singular, I started to sleep again. I started to smile again. I started to sleep with my laptop again (I know—terrible sleep hygiene, but I needed my poems that close).

What I learned along the way is that being good at many things is fine. (Sorry, Galway: that’s not the problem.) But giving my attention to so many things that I move none of them forward is no longer an option.

I want a life of passion and purpose. I want to do the writing and parenting and living I am here to do. The path to more of what matters is less of everything else.

===

Are you good at too many things? What could you do less of – so you have more space for you most essential work? I’d love to hear! And I’d love to help! Join me in Salem, OR on February 19 to clarify a single purpose for your writing and publishing life—and chart your course for getting there!

More at sagecohen.com

The post Are you good at too many things? appeared first on Sage Cohen.

January 18, 2019

Writing into the places they once occupied

A few weekends ago, I drove myself to the beach. No partner. No dog. I walked alone for hours.

As I walked, I photographed the beach, full of emptiness and light. Standing at the thrashing eclipse of continent and ocean, I photographed myself smiling at nothing and no one.

Until my beloved Machi died eight months ago, I had never been dogless in Oregon. Never been to a beach without the amplified joy of my dogs. Never wanted to be.

For more than 30 years, my life rhythms revolved around a progression of eight pets: shopping for supplies, feeding, walking, scooping litter, driving to rehab, cleaning bodily fluids from every surface, sitting, sleeping, and working with an array of bodies draped over my own, and endlessly adoring my rag-tag pack.

Until a ricochet of loss in which my relationship with my boyfriend ended and my dog died, followed a few months later by my cat.

I was shedding beloveds and selves like a rose drops its petals: a scatter in the wind.

Who was I without a dog’s desire as my map, Machi’s combative canine inclinations as my hair shirt, my pockets free of poop bags?

As I studied my unaccompanied set of footprints in the sand, the allegory surfaced in which a person is feeling abandoned by God. When she asks why she no longer sees God’s footprints alongside her own at a time of such difficulty, God answers, I would never leave you. During your times of trial and suffering, when you see only one set of footprints, it’s because I am carrying you.

I don’t know what this means to me, exactly. Only that in parallel with absence, I became aware of presence. As I walked, I was keeping time with a chorus of souls. Every being I have loved and lost was somehow with me. Splashing the lens of my life and leaving a salty residue of grief and joy. Making the crescendo of my solitude more precise and penetrating.

Next surfaced these lines from Marge Piercy’s poem All Clear which was taped to my dorm room mirror in my college years:

Loss is also clearance

Emptiness is also receptivity.

No, I cannot pretend:

the cells of my body lack you

and keen their specific hunger.

Yet, a light slants over this bleak landscape

from the low yellow sun,

a burning kite caught in the branches.

There is loss and there is light. There is a gaping space in which we are no longer occupied by the great love that has occupied us. And this gives us room to imagine how to begin again.

Like the relentless enormity of ocean, Elizabeth Gilbert’s “I am willing” moved through me in waves. I am willing. I am willing to feel this grief. I am willing. I AM WILLING. I walked. I sobbed. I gave thanks. Then I drove home.

The next day, my son wanted to know what happened to the screensaver I’ve had for his entire life: a photo of my dog Henry on the beach in the year 2000—smiling beside an exhausted tennis ball, encircled in a heart-shaped pattern of his own footprints.

In its place was this photo.

Because this is what our life is like now, I told him. An entire coastline awaiting our footprints.

===

What surprising grace have you found in loss? And how has writing helped you occupy the empty spaces? I’d love to hear.

The post Writing into the places they once occupied appeared first on Sage Cohen.

January 3, 2019

Are you believing hard enough?

Hello, and happy 2019!

It’s good to be with you on the fresh, unwritten page of a new year.

At this time when many of us are choosing or recommitting to habits, practices, or projects for our writing lives, I want to help you address a sneaky dynamic could have you spinning your wheels.

Here’s what happens.

Sometimes, our desires are in conflict with our stories about who we are. But the stories run so old and deep, we don’t even know they’re running the show. So they’re creating interference we can’t perceive—and therefore, can’t address.

For example, throughout all of 2018, I wanted to lose 25 pounds. I worked really hard at making it happen and didn’t accomplish much. It took me most of the year to figure out why: I believed I was safer being overweight (and therefore, in my mind, invisible).

In my writing life, as well, I have projects that matter deeply to me that never get traction for similar reasons: I feel safer being less exposed.

So here’s what I did, what I’m doing, and what I will do until my story about visibility has been rewired.

I listened many times to this podcast from Brooke Castillo of The Life Coach School about what it means to believe hard.

Then, I set out to believe really hard what I know to be true: that I am safest at my optimal weight. Because a healthy, fit, well-fed body is truly at the least risk, right?

And I’ve been believing equally hard that I am safest when I write and publish the stories and poems that dig deeper than I’ve ever been willing to go. Because that is what I believe am here to do: tell and share the truth of my life in writing—and invite others to do the same.

I am believing myself all the way to the other side of my fear, to the person I will be when I am entirely willing to be visible. I am standing in the shoes of this visible-future-me. And I am exhilarating in her deepest, most authentic and vital life. So that when I get to that target weight and that terrifying publication, I am ready. I am already there. And these successes are simply catching up with where I knew I’d be all along.

I think of our desires, actions, and stories as strings on the sitar. One plucked string invites the others to sing. Believing hard is that string we commit to that calls the rest of us forth in fierce agreement about the way forward.

If there’s an area of your writing life where you’re stuck or struggling, see if there’s a story underneath in need of revision. It takes courage, practice, and some new skills to believe stories we’re not in the habit of believing.

You’re just the person for the job!

I’ll be sharing more about believing hard – and my other top strategies for writing and publishing fierce – at the Willamette Writers of Portland monthly meeting on Tuesday, January 8. (Note: NEW LOCATION!) I hope you’ll join me there – or at another event in Oregon or Washington this year.

What will you believe hard in 2019? I’d love to hear!

The post Are you believing hard enough? appeared first on Sage Cohen.

November 25, 2018

What if we’re all swimming in duckweed?

The day after Thanksgiving, my ten-year-old son and I took a walk through the Reed College Canyon, a sacred wild place that is practically in our back yard.

I’d told him about my favorite pond full of algae where the ducks like to hang out. As we turned the bend and the small body of water came into view, my son laughed.

“That’s not algae, Mom, that’s duckweed! It’s a plant ducks like to eat.”

An enthusiastic naturalist and patient teacher, my son led me to the pond’s edge, found a stick, and swished it around in the water to show me how the top layer of green was actually a mass of tiny, flowering plants that somehow stay alive on the surface of still water.

“Isn’t it remarkable that the ducks are literally swimming in their food?” I asked my son.

“It seems perfectly natural to me,” he responded.

Such a refreshing assumption—that it’s perfectly natural to have everything we need, right here and now.

I thought: What if we’re all swimming in duckweed, and we don’t even know it?

And how would it change our (writing) lives if we did know it?

I recalled some of the triumphs I’d heard from my community of writers lately: people dedicating their first 20 waking minutes to morning pages; people carving out space to write thousands of words per day as part of NaNoWriMo; people with generous partners and children who handle household tasks on a regular basis, so they can write; people plotting out highly successful writing projects and careers on napkins in five-minute margins before school pick-up.

And yet, we’re so often focused on what we lack and what’s in our way, instead of on how much we already have and are accomplishing.

What if we all have exactly the right pen, plot, inspiration, circumstance, and skillset to do the work we are here to do—right now? What if everything about our lives is already enough?

What if our primary opportunity is to notice that we’re swimming in duckweed, let ourselves be nourished by it, and be grateful?

What if it were perfectly natural to write what we’re here to write—in as much time, with as much effort, as it takes. What if it’s the water we are already swimming in?

====

I’d love to hear about the duckweed you’re swimming in! Please, please, please, tell us about everything that’s going right in your writing life in the comments below!

The post What if we’re all swimming in duckweed? appeared first on Sage Cohen.

November 20, 2018

What are you grateful for?

As Thanksgiving approaches here in the U.S., I’m thinking about how the practice of gratitude has rewired me.

I used to think of gratitude as a spontaneous response to good things happening. In recent years, however, I have come to understand that gratitude is much more than an automatic byproduct of positive experience. Gratitude can actually be our emotional and intellectual baseline, if that’s what we choose.

What I mean is, we don’t have to wait around for the things we want to happen to feel grateful. We can simply find things to be grateful about no matter what happens, or how far afield we may be from what we desire. From this vantage point, everything we experience gives us something to appreciate, no matter how difficult or seemingly inconsequential it might be.

I saw this modeled recently by a workshop leader who enacted smashing his thumb with a hammer. After shouting bloody murder, he said, “Boy am I glad that doesn’t happen very often.” And then, “Wow, check out all of that sensation in my thumb! I’m so glad I have nerves to tell me that I have injured myself.”

It is uncommon to interpret an unfortunate event with gratitude. But this leader demonstrated that it is always an option. When we find ways to appreciate a difficult experience—or at least use it to appreciate how great our life was before and after it happened—we set ourselves up to feel empowered. After we experience our feelings, we get to decide how the events that happen to us affect us.

My first memory of choosing gratitude over, say, revenge was in college. I had broken up with my first love, and the emotional pain was so intense that I feared it would kill me. A few weeks in, when I knew conclusively that my body would keep going no matter how sad I was, I focused on that: being alive. If I had survived this heartbreak, I could expect to survive the losses of future loves to come. This was good news! When I shifted my gaze from pain to gratitude, I stumbled into discovery.

And of course, this loss helped me trust that I could weather the disappointments of my literary life as well. Over the years, I have come to appreciate each publication that rejected my work for the opportunity to work harder, write better, and find a truer fit for my work. And I have deeply appreciated the teachers, editors, colleagues, and writing group friends who have given me uncomfortable feedback that has challenged me to grow.

In every so-called mistake, failure, and disappointment, I have been further refined as a writer and a person. There has been so much to appreciate.

Of course, every day of our writing lives, endless things also go right. Choosing gratitude doesn’t just help us transcend our bad fortune. It also helps us integrate our good fortune. Gratitude is just as important—and just as easy to overlook—when things are going well as when they’re not.

When you acknowledge yourself for how hard you’re working, it can make a significant difference in your endurance and your mood. When you show up at your writing desk at the time you promised yourself; when you move through the angst of the blank page; when you complete the first draft, the revision, and the next revision; when you are willing to get feedback from your writing group; when you have the fortitude to research submissions; when you the courage to submit and resubmit your work; these are all opportunities to appreciate yourself.

When you notice and acknowledge how capable and courageous you are, you anchor this in your being. You start to learn that you can count on yourself. Whether or not you ultimately achieve the result you want, you have numerous successes to refer to that can help you more deeply receive your epic wins or more effectively redirect your efforts to try again.

A writer friend told me that when his first book came out, he sent out a wave of thank-you letters and emails to all the people who had influenced his thinking and writing. Then he launched into all of the mandatory marketing and press outreach. He explained that framing the whole experience in gratitude reduced his anxiety about whether the book would sell and changed his approach completely.

Gratitude anchored him in the field of influence from which his book was called into existence, and it kept his focus on the service his book was offering. This quickly put his book in the hands of a global community seeking his wisdom.

When we focus on problems, we generate dissatisfaction and resentment. When we invest in fears, we can destabilize ourselves. But when gratitude is the ground on which we stand, we can be satisfied with life exactly as it is and relax into the unknown, while becoming more receptive to all that we desire.

What are you grateful for in your (writing) life?

P.S. Because writing thank-you notes is basically my spiritual practice, I made these. And now they’re available to you!

The post What are you grateful for? appeared first on Sage Cohen.

October 26, 2018

Support for you > from Writer’s Digest + me!

As an instructor and coach, I am passionate about your writing practice giving you the results you want—whether that’s income, healing, refined craft, publication, or a platform for giving service.

That’s why, in partnership with my publisher, Writer’s Digest, I’m offering two different kinds of support for writers in November! I’d love to accompany you as you take your writing life forward.

FREE! Writer’s Digest Author’s exchange Facebook Group

Join us from November 5 to 11 to discuss productivity, poetry, and the fierce writing life

The Writer’s Digest Author Exchange Facebook group offers a lively community + engaged conversation about the writing life—guided each week by a different author. As the group’s host from November 5 to 11, I’ll offer tips, prompts, polls and resources, answer your questions, and give away lots of books. We’ll have a great time covering a range of writing topics—from productivity to poetry to the fierce writing life. It would be great to have you with us. Click here to join the group!

Writer’s Digest University Virtual Conference for Freelance Writers

WEBINAR: Success Strategies for a 6-Figure Freelance Writing Business

Sunday, November 4, 2018 // 12:00 to 1:00 p.m. PST

Writer’s Digest University is offering an exclusive virtual conference for freelance writers! On November 3 and 4, the Freelance Virtual Conference will provide expert insights from SIX accomplished freelance writers and authors on taking your freelance work and business to the next level. Experience the education, camaraderie, and opportunities of a live writing conference without ever leaving your home!

I’ll be teaching Session 5: Success Strategies for a 6-Figure Freelance Writing Business

Freelance writing success depends as much on solid business systems and practices as it does on great writing. In this session, I will share the top five success strategies I’ve used to build and sustain a six-figure writing business for 20+ years. From managing time, money, and projects to building your brand, customer base, and presence in the market, you’ll learn how to lay a foundation of productivity and prosperity for your writing business. So your best writing can fund your best life.

Want to personalize your participation?

If you have questions or topics you’d like me to cover in either of these experiences, please share them in the comments below. Then, I’ll do my best to answer them!

Hope to see you virtually next month!

The post Support for you > from Writer’s Digest + me! appeared first on Sage Cohen.