Kristen Orser's Blog, page 3

January 29, 2014

Why am I afraid to be a female poet?

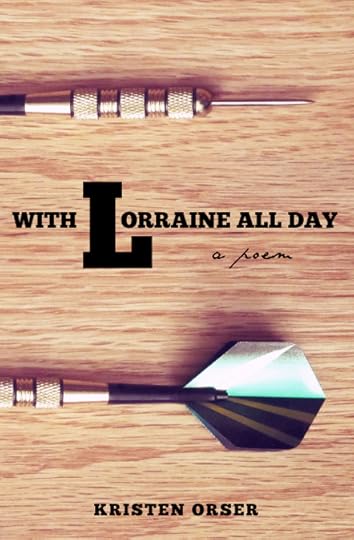

In April, this book is coming out and I could not be more excited. Ryan W. Bradley has been a dream to work with; he has enabled me to think about visual representation and what the work means with an image.

Here’s what I learned about book design: I’m anxious about gender.

A few potential choices we shared shouted, “woman poet.” Echoed even.

I can’t help but wonder why I resisted that style or affiliation since, let’s deal, I am a woman poet: Why am I afraid to be a female poet?

Here’s an answer that I think makes sense: we’re always a bit afraid of being what we are. I think about a caterpillar and how it has to digest itself, practically melt before it becomes a butterfly. It’s death inducing to become what we are going to become. Does that sound too new age? Or maybe it’s too dismissive of free will? It is scary to do what feels natural.

Back to the problem at hand. Something about a book cover that pegged me, pinned me down as a female poet, felt limiting.

This needs to be addressed: there are still limits, still a sense of limitation.

VIDA has kept track of how male writers are disproportionately represented – and reviewed – in major publications like The New York Times. The limitations, restrictions, and feeling of being underneath isn’t new or particular to me. But shouldn’t I be resisting? Shouldn’t I want to shout out some kind of feminine chant on my book cover to buck the numbers? The ethics of my resistance make me stutter, pause, grow silent.

It doesn’t matter if the limitations are real or perceived, so I’d rather avoid that conversation for now, the fact of the sensation remains. I worried. People would anticipate a certain “type” of language, process, content, etc. I imagined the books relegated to Sweet Valley High status. I imagined people only thinking about the femininity of the work. Only reading, even, for the work of being a woman. And, yes, that those affiliations would somehow soften or lessen the work.

Who doesn’t want to be associated with Sappho’s fragments? With Laura Riding Jackson’s inquiry and questions? With Dickinson’s em dash? With Niedecker’s short lines?

Why did I seek out a neutrality? Is neutrality a kind of cover, a disguise?

More questions than answers. Why does Sappho’s sexuality get addressed more than the craft? Why did Jackson repudiate any associations with feminism? Why is Dickinson characterized as a demure, quiet woman in a white dress? And why did Niedecker’s For Paul get put on a publishing back burner because of Zukofsky’s ambivalence?

Why, in the list of favorite female poets that I listed, did I focus on things that are “soft” or “abstract” and not firm? The unfinished fragment. The question. The punctuation of lingering. The brevity. Does it matter that these are culturally valued as softer than sentence, answer, period, length?

What I’m saying is, there’s a history of associations and I felt the reality of that history (emphasis on the his) when I thought about a cover design. I can’t shake the feeling, the ethics that came along with it.

January 27, 2014

Anxiety and mommy hood

I “come out” as an anxious person to my students about half way through any class, once we’ve had a few “kumbaya” moments. Lately, I’m wondering about how and when I’ll tell my son.

I realize he probably already knows.

Avery gets ready to go on a trip, and shows no signs of nerves.

Consider the origin of this fear, at least, the first instantiation of it: In first grade, Jen K. invited me to her house after school. I remember sitting on the bus, looking at her house, which was big and fancy looking to my little eyes. It wasn’t like my house and, she boasted, there was a pool. I wanted to go. I wanted to see inside that big house and swim in that pool. She told me her mother would call my mother for a playdate. She got off the bus and I stayed, thinking about what that would be like, what the inside of the house would look like, what kind of toys she had, and what games we would play.

Her mom did, indeed, call my mom. I said I didn’t want to go. I cried. I remember asking my mom questions: what would I say to her? how would I know how to play the games she played? what if everything was different from how things were “here”, at my home?

In school, I had lots of friends. I was loud, playful, always laughing, and generally in trouble for talking too much. I was a regular and jovial kid. I was more than regular, I was social and, even, popular. People wanted to play with me because I was imaginative, fun, and loud.

Outside of classrooms and organized activities, I was alone. I played a lot of games in my head, almost completely silent.

My mom let it pass and when Jen’s mom called again, the same thing happened. This occurred three times and Jen stopped sitting with me on the bus. Then, my mom was concerned.

My mother set up a play date and drove me over, without asking me. I was terrified. I kicked and cried. I felt lumps in my throat.

I can’t explain this, I can only retell it. It’s the first occurrence of many. I cancelled RSVPs to childhood parties too. Before parties, play dates, and phone calls to friends, I was terrified and uncomfortable.

I still am.

I want to tell this story better—with some reflection of insight, maybe even details that make it “writerly”. It’s not a well told story and it can’t be. I don’t understand it and I still experience this kind of anxiety before any outing. My partner’s gotten used to it, has coached me through it, and I can get myself out to some lunch dates with colleagues or nights out with a few girls, but it’s not easy.

Now, Avery is a new reason to see people. We go to yoga classes, park dates, and some early morning get togethers. I think about him and not my own fear, but I still can’t always get it together. He has to see this. He has to know that I’m nervous. Does he feel nervous because I am? Am I giving him this same anxious feeling? Is it genetic? Will he see me as lonely?

I joke with my students that, when I get anxious, my tongue feels huge so they’ll know I’m nervous because I’ll trip over my words. They always laugh and I mimic what it will sound like so that my anxiety is—and might become—a performance, something I can control.

Being a mother with anxiety is something I thought about all through pregnancy, but I didn’t get anywhere besides the usual worry. I haven’t gotten to a place where I can understand it, understand how to tell Avery about it, and control it for him. I’m worried about being worried, but I’m conscious of it.

I’m practicing too. I’m getting out the door and talking.

January 19, 2014

April, a new book

I’m happy to tell you all that April is the month with the shiniest star on my calendar.

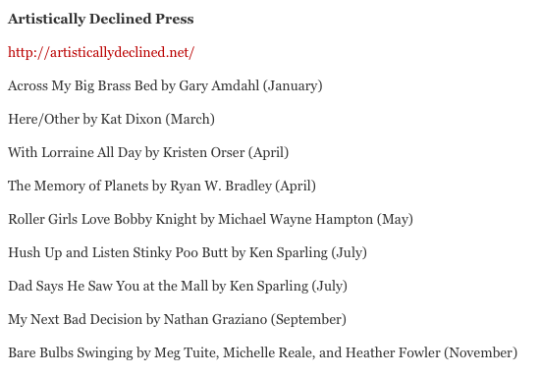

Ryan W. Bradley is at it again, making faces melt and hearts grow. I mean, he’s publishing an excellent 2014 line up as usual with his ever so clever, ever so daring, ever so “who cares what’s in or out, let’s publish what’s GOOD” Artistically Declined Press.

Of course, I’m oogly eyed about Kat Dixon’s work, Here/Other.

A three way collab, Bare Bulbs Swinging, has also caught my attention by Meg Tuite, Michelle Reale, and Heather Fowler.

And, since I really liked Teaching Metaphors, I can’t wait to see what Nathan Graziano is up to in My Next Bad Decision.

I’m keeping my body from exploding with excitement about his graciousness to publish my own work With Lorraine All Day.

Over the next week, I’ll talk about collaborating with Ryan, which is always a good experience, cover design, and the forthcoming books impetus.

January 13, 2014

2014: the year of publication

The baby takes time. He has taken time.

Today we went ocean-ward and Avery looked years instead of months. His face changes. My hands age too. We watched the water shift around, caked sand on our feet, and accidentally ate a bit.

I admit this: I didn’t love staying at home. Mothering, I loved. Staying at home as mother, as all day mother, that was harder. It’s been two weeks since I stopped teaching and it’s taken the full duration of that time to see what this means, how fortunate I am, and what I’m getting to experience. I’m still going to be researching, writing, and pushing myself to publish this year, but I’m less anxious to make and tackle a big list.

Financially, this is crazy. Emotionally, this is wonderful.

But I promised the baby and myself that this year would be a year of courage. Publishing poetry has been an act of courage, but my children’s books are something harder. There’s so much doubt about their merit, purpose, audience, and the line. They are my darlings.

My friend Emily is, hopefully, illustrating one of them and I’ve discussed further illustrations with another friend, Dwight. What I like about Emily’s work is its playfulness. I think she’ll tap into the way the story is sad and magical. She won’t overdramatize one emotion over the other, but she will see how the two are the same. Dwight is influenced by other cultures and strong colors like red and black. That kind of fortitude against the sometimes soft, sometimes lingering lines seems magical.

I’ve thought about the birds in the first story a lot: I see them as ghosts. Like they almost aren’t on the page or they’re fading from page instead of lifting off or flying.

But with the boy, the main character, they’re more capable and present.

January 7, 2014

getting ready for the GFAs

The Good Food Awards are a little star on my calendar next week. I’m excited for two reasons: Good Food (and bevies) and a night out sans baby. I doubt Avery would dig the charcuterie plates.

I did a little write up for Sprudge about the coffee portion of the GFA and judging, which you can read here (note, I didn’t attend judging as the article preface says, that’s a closed-door).

Here’s the thing, people get down on judges and judging. It’s never “the way” people want it to be and standardization makes people’s faces turn green. Everyone gets homogenized fears about homogenization.

In my little world, writing and the arts, judging is this strange thing we touch with a stick. In my poetics class last quarter my students commented on poems by saying, “It’s not my place to judge this” or prefaced comments with, “I don’t like to judge other people’s work, but…”. We talked about this less than I’d like to. Ideally, I’d like an introductory poetry class to be about assessment, critique, and how we talk about poetry. This was not that class. This was the “get comfy writing” poetry class where we dabbled in how to talk about and read poems, but focused on how to get words on the page. When we talked about it there was a lot of “art can’t be judged” input and the word subjective was thrown about the room. It stuck. It stuck too much.

I get it. And, I don’t.

When I make something, I expect it to be judged. Actually, I want it to be judged. I want it to roll around in someone’s ear, head, and stomach; to leave little snail trails or make a cobweb inside of them. I know—or maybe I believe—judgement and critique is part of the work. The reader and the experience enlarges the work and, if the feedback is heard, changes and develops the work. That whole reciporcal thing is important to me.

Bottom line, my material is language. Language will gather more language. I’m not sure everyone will be able to relate to my language, to the particular way I assembled or navigated that language, but the judgement isn’t about “relating” to poetry, it’s about judging it for how it is working. Sometimes language works and sometimes it doesn’t right? We’re quick to judge and assess how Obama is using (even innovating) words and we know that rhetoric and fields (especially in politics) “shapes” the way we think/react, so it seems pretty easy to see how poetry can be critiqued. Not as “right” or “wrong,” but for what it does with language; how it uses language to do something. There should be doing, even if it’s just trying to find the way to say something.

What’s harder, I think, is “who” gets to judge. If poetry is for the people, if readership is democratic, how do we get that audience? And how do the judging panels and “elite” communities work toward the goal of enlarging and inviting readership? I don’t have answers for that, but I see that issue – the who of it all – as way more deep than “why” and “how” do we judge.

For the GFAs, judging has this same problem. The food, bevies, and the practices of making (including the way the ingredients are grown and processed) are improved by having to meet a higher standard. This year, that standard included sustainability. I’d rather we have this standard because it improves the work, the working conditions, and the product. Who doesn’t want to preserve and conserve the environment? I don’t have any issue with there being standards, assessment, and judging that better things.

This isn’t homogenization, this is innovation.

I do, and the article doesn’t cover this, wonder about the democracy/participation question. The cost of tickets is high. Who is experiencing the GFAs? Are we truly reaching the population? Is part of sustainability not just the growing practices, but inviting people/consumers to the product?

I would have liked to spend more time with Geoff Watts and his value that the product, the coffee products, are available for consumption. This is different from most coffee competitions and it’s important. I want to pick his brain about that…hear me Watts, I’m coming to pick your brain (and I haven’t cut my nails in weeks).

When Jesse started working for Verve, he told me about how most coffee farmers don’t get to taste the final product. They don’t always get to taste the cup of coffee that coffee plant, their crop, goes into. It really turned a switch in my mind: All that work, all the value of that work, and no experience or product?

If we want to escape the monoliths of Monsanto and Purdue, if we want to encourage small batch and well crafted food that is “good” in many ways, don’t we also want to destabilize the traditions that have encouraged these food-powers? The best destabilization seems to be inviting more acts of stewardship that are not just environmentally sustainable but are also sustainable in terms of the people. Are the people involved earning a living wage? Are the people cared for and treated well? Are all elements of the product traced so that the people are accounted for?

I don’t have the answer to this question and I’m not sure I know where the GFA and judges stand on accountability and sustainability that attends to the people, but it’s on my mind. It’s coming to the front of my mind.

January 4, 2014

keeping track, keeping count

I started a blog for myself. To keep track of publications and whereabouts. I did this after a mentor told me a story about “double publishing” that made me weak in the knees. It’s seems so painfully simple and easy to mess up by sending the same piece out and forgetting to follow its tracks. This is especially hard for someone like me who over-edits and has a tendency to have the same piece become something else, but maybe stay “too much” the same. I worry.

In all this worry, I try to keep track and count.

Happily, sometimes there are people who do it better than me and for me. Thanks Sprudge, for running my review of Duende again. It’s a good reminder, during the new year and as a new mom, that I do actually write and sometimes I even publish.

January 2, 2014

Conference-ing

One of the research aims is the status of reading. Jesse says, “I can’t help but want a kindle” because he watches the travelers read with their fingers. I tell him I like books.

No, I don’t think extinction is near. The book, the tactile experience as a whole, is resilient. People will always return to touch and we might re-see touching. I think of Barthes saying that literature should try “to save its skin.” Did he mean the book? Did he mean the fleshiness of reading?

When I was little, I read everything by mouthing the words. I didn’t make a sound, but my mouth moved across the words. I think most kids do this right? We see them read with their bodies.

So, yes there’s so much skin: our own and the books’. Avery ripped apart Pat the Bunny, he tore into it with his teeth and the spine fell right out. The whole book is about touch: pat the bunny, play peek a boo with Jack, touch Daddy’s beard, etc. And Avery went right along touching.

For me, the book is all about touch and its status seems, in our most innocent play with books, to still be about touch. Jesse wants the kindle because he wants to collect, it’s still an object. But I do want to know how these objects are different and what’s at stake in keeping ourselves able to touch, interact, or—in Avery’s case—consume a book.

December 23, 2013

Train to Albany

There’s an Amish family in the train car ahead of me. The girl is quiet, is covered for modesty – as is her mother – and sucks on a pacifier. My son is taking his hat off and laughing with a kind of manic sound that’s going to become tears. I have to remind myself of two things: this too shall pass and the quiet baby girl cries too.

Heather says it’s good Avery cries and laughs, that he can communicate his needs. Most of my friends say that, but in my vulnerable moments, of which there are many, I can’t help bit wonder why he is always making so many sounds. Does he already know how hard it is to be heard? Has the world already shown him the kind of noise he has to make to generate an echo, to fall into an ear, to fill the space?

I’m thinking these things at the same time I’m trying to listen to myself. Intuition. People keep saying that word. I doubt it’s meaning, existence, and practicality. But I hear something in the space between my brows that suggests a restlessness. Why haven’t you published your children’s books? Why are you waiting to become a writer? There’s an endless series of why questions I’m trying to attend to.

Is it possible that my son has already seen me push those inner sounds down? Is he talking because I’m not?

I never wanted a blog. I wanted a place to keep track of things: mostly poems, publications, and sometimes time. But the end if a year makes us think of beginning, the new year, what’s coming. What’s coming is a new need; I need to collect, to collect so that I can listen.

Avery, your name sounds of wind and birds. I’m going to whistle some. I’m going to send some in the wind and see where it drops down. In Buffalo, we are past our knees in melted snow. It’s not the winter I wanted, but it’s the place I decided to turn around and think about that time I saw a fish in a frozen pond and didn’t want to think there was resemblance.

October 24, 2013

Notes Toward a Review

The days are domestic: I look out windows while washing dishes, I sing songs to Avery while folding laundry, and I trim weeds in rosemary while fog rolls out.

There’s much fog. So much that we walk though it, in it, and with it. I’ve seen him squint in both the sun and fog. This is California.

Domesticity, this haze, isn’t a tethering; but it teeters toward feeling bound. Avery’s body stretches out while my own hunches over. At night, we roll into each other and, in the morning, he wants to be held again. He becomes a heavy brooch. He pins to me and I read about feeling “touched out.”

Yes, touched out and out of touch. The work of writing goes unwritten, but stays in my head as a composition always in process.

For almost a month now, I’ve been taking notes for a review of Sean Thomas Dougherty’s book Scything Grace. His work and my domestic moment hold the same narrative of being wrapped, swaddled in still moments.

Dougherty’s book came at the best and worst time: reminders of Lake Erie, grapes, men with berry-stained hands, the way sweet somethings rot. It also gave me a kind of survivor’s guilt for having Avery, for watching a baby grow, and for, sadly, “getting out” of Buffalo (my father’s words). The poems and the baby make me feel papery. And yet, there is so much of the conditional in his syntax, so much reliance on “if” and “yet” and “perhaps.”

Dougherty is asking the language to shift and bend for his own feelings. He is attached to the body of “how things are said” and finding that there isn’t room for “what needs to be said.” I see him sitting in bed with a fever and looking for words, sentences, and poems to complete his thoughts and respond to the fever. Last month, I had a bout of mastitis and Avery stayed in bed, ate, and made it go away. It’s been remarkable to see another body correcting another (my own) body.

At home, in Buffalo, there is an old wooden house I played with as a child. There were cloth bears that lived in the house: a mother, father, son, daughter, and baby bear. They lived in the house and I made them talk. Now, I am waiting for Avery to tell me if I’m doing okay, if he’s doing okay. I am looking out the window and receiving omens from the way the sink clogs, the way the birds spit out shells. I am reading Dougherty and understanding this feverish position of wondering when we’ll know how to say something that means something, how we’ll know when to say that we’re all doing okay.

October 23, 2013

On Naming

Jill Magi phrases my own impostor syndrome eloquently:

I am not at all certain of the currency of “small press publication” and “I am an experimentalist”—aspects of my biography that until now have felt somewhat normal [...]I wonder, are there others around me who experience language as gangly failure, as plastic, as inconclusive, as desire? I send out this wish to meet them.

Sent and received.

I tell my students about the anthropocene and, like good scientists, they mostly wonder about its validity as a geological fact. I think about the word and how we are coming to agree or disagree about a word, a combination. Doesn’t this move them? Don’t they feel the shuffling of their tongues trying to say the word and, by saying it, admitting that something has happened, something has been named?

It might be more dreamy to look at facts in this case. More romantic to wait for some “truth” about time instead of accepting an abstract. How infrequently are my own experiments and abstracts more “right” than their concrete, hard, and researched facts. But this might be one case, one instance, of an abstraction of necessity. I’m reminded of Breton,

Our brains are dulled by the incurable mania of wanting to make the unknown known, classifiable. . .

Andre ́ Breton, First Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924

If the word the anthropocene is a failure and we’ve already named it (ironically, the “it” being our own failure to do not harm), can we pretend it away again? Isn’t it enough that we desire to name what’s happening?

I think about naming Avery. I’d wanted to name him Bird, but gave him a name that’s “for the birds” (as I say), has the sound of birds, wind, and things that flutter. He was named before he was born and it made him more real before he was, well, real. It was a scary moment with language; it was the kind of moment where “the word is not the thing” echoed in my head and felt deadening. What was the thing? What did I name? What did naming it do?

My coworker thinks words are names we give things so we can just talk. I think that’s too simple. She says it’s my field, my own tie to Wittgenstein and I remember the day Albert said that the german word for sentence, der saltz, translates to also mean “leap” or the day Stephen drew the two worlds he imagined Plato envisioned on a napkin at BJ’s. It’s a leap to get from the thing to the description of the thing.

The fact that I think this and can’t pin it down leaves me lacking. I feel unqualified. I feel, again, like a philosophy 101 student or the way I felt my first day of grad school when Lisa walked in wearing cowboy boots and Aaron’s poem worked like a machine.

That might be the trick though, the trick to staying in my field: a constant renewal of inadequacy. I’m starting to think that feeling and the constant re-affirmation of needing to try, to keep up, to make, and to think through it all over again is the driving force.

I look at the students and they know so much more than they’ve been told they know. They know so much more than me and I know so much more than them. I wonder how we can start to talk about how dizzying it all is and how exciting it can be to seek a bit of focus, a bit of precision. They come again to “fact” and “how did you get there” and I come again to, “can you help me trace the way?” I wonder where we’ll meet during the research paper.

To feel a bit more adequate, I poem-ed. And, look, even won an award. Thank you SLAB.