Karl Shuker's Blog, page 17

April 19, 2020

IN PURSUIT OF THE PATAGONIAN PLESIOSAUR

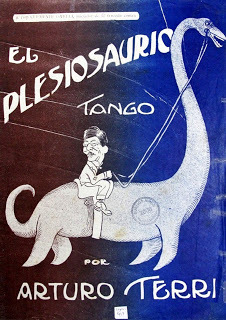

Front cover of sheet music for the El Plesiosaurio tango, featuring an amusing caricature of Dr Clemente Onelli riding a plesiosaur (public domain)

Front cover of sheet music for the El Plesiosaurio tango, featuring an amusing caricature of Dr Clemente Onelli riding a plesiosaur (public domain)Several lake-dwelling cryptids of the long-necked persuasion have been reported from South America down through the years. However, the most publicised of these freshwater mystery beasts was unquestionably the so-called Patagonian plesiosaur, which at the height of its fame even received coverage in the august journal Scientific American.

In January 1922, Dr Clemente Onelli, Director of Buenos Aires Zoo in Argentina, received a letter from a Texan adventurer called Martin Sheffield, who had spent a number of years as an itinerant prospector living off the land in Patagonia. In his letter, Sheffield claimed that some nights previously, after pitching his hunting camp close to a mountain lake near Esquel, he had encountered a strange animal:

...in the middle of the lake, I saw the head of an animal. At first sight it was like some unknown species of swan, but swirls in the water made me think its body must resemble a crocodile's.

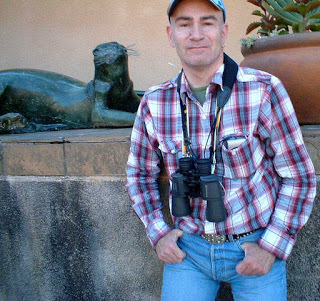

Dr Clemente Onelli (public domain)

Dr Clemente Onelli (public domain)Not surprisingly, Sheffield's description conjured up images of plesiosaurs in Onelli's mind, and also reminded him of a somewhat earlier report. In 1897, he had spoken to a farmer living on the shores of Patagonia's White Lake, who informed him that a strange noise was frequently heard there at night, resembling the sound that a cart would make if dragged over the lake's pebbly shore - but that was not all. On moonlight nights, a huge beast could be seen in the lake, with a long reptilian neck that would rise high above the water, unless disturbed - whereupon it would instantly dive and disappear into the depths.

Heartened by these and other reports, Onelli organised an expedition to follow them up, which duly set forth on 23 March 1922, led by José Cihagi, superintendent of Buenos Aires Zoo. It eventually reached the lake where Sheffield had experienced his sighting (and which is known accordingly today as Laguna del Plesiosaurio – 'Lagoon of the Plesiosaur'), but with the approach of winter further explorations were abandoned and the expedition returned to Buenos Aires.

President Theodore Roosevelt (public domain)

President Theodore Roosevelt (public domain)Interestingly, Sheffield had also previously contacted former American president Theodore Roosevelt concerning the swan-necked beast that he had seen in the mountain lake. As a result of this, Roosevelt, who was famed for his hunting skills, had apparently pondered over whether to launch a search for it himself, but he never actually did so, and he died in 1919, three years before Onelli's expedition set out.

And so it was that apart from a jaunty tango entitled El Plesiosaurio (composed in 1922 by Rafael D'Agostino, with lyrics by Amilcar Morbidelli, and sheet music depicting on its cover a caricature of Onelli riding a plesiosaur) plus a brand of cigarettes also named after it, nothing else of note emerged regarding the putative plesiosaur of Patagonia for many years - until the 1980s. Since then, however, numerous reports have been aired by the media concerning a similar water beast, nicknamed Nahuelito, which is said to inhabit Nahuel Huapi, a 204-square-mile Argentinian lake ensconced amid the Andes winter-sport resort of Bariloche.

Nahuel Huapi Lake (© David/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

Nahuel Huapi Lake (© David/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)Auyan-tepui is a lofty tepui (table mountain) in Venezuela, one of the inspirations for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's classic cryptozoological novel The Lost World – an exciting work of fiction in which the plateau at the summit of one such tepui is populated by dinosaurs, pterosaurs, plesiosaurs, and other prehistoric survivors.

In 1955, however, during an expedition to Auyan-tepui, naturalist Alexander Laime allegedly sighted some creatures that gave the more optimistic zoologists reason for believing that the theme of Conan Doyle's novel may not be wholly fictitious after all.

Auyan-tepui (public domain)

Auyan-tepui (public domain)As documented in my book Still In Search Of Prehistoric Survivors (2016), Laime had been searching for diamonds in one of the rivers at the summit of this isolated tepui when he spied three very strange beasts sunbathing on a rocky ledge above the water. Superficially seal-like, closer observation revealed that they had reptilian faces with disproportionately long necks, and two pairs of scaly flippers. Drawings that he made of them at that time are reminiscent of plesiosaurs. There is, however, one very unexpected feature - none of them was more than 3 ft long.

Could they have been young specimens? Laime believed that they were adults, but belonging to some pygmy species of plesiosaur, whose small size has enabled it to persist into the present day without disturbing the ecological balance of this enclosed system. More conservative opinions favour some long-necked type of otter as a more plausible identity, whereas others have even likened them to a crocodile.

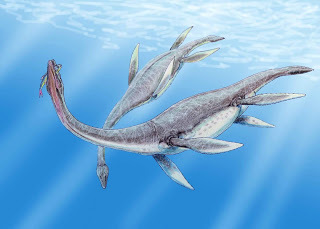

Plesiosaurs (© Dmitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia -

CC BY 3.0 licence

)

Plesiosaurs (© Dmitry Bogdanov/Wikipedia -

CC BY 3.0 licence

)In 1990, Auyan-tepui played host to an expedition led by biologist Fabian Michelangeli and including scientific reporter Uwe George, for whom this was his sixth exploration of a South American tepui. During their visit, Michelangeli and his brother Armando spied a silhouette of a beast closely resembling those reported by Laime, but as they drew nearer to investigate, the beast plunged into the river and disappeared from view. As for various German TV reports claiming that one had actually been captured, these were inspired by the procurement of nothing more spectacular than a common species of lizard.

So for now, at least, we have only the distant refrain of a long-forgotten tango to remind us of how a US President had almost set forth in South America to seek a putative prehistoric survivor.

Theodore Roosevelt as Badlands hunter in 1885 (public domain)

Theodore Roosevelt as Badlands hunter in 1885 (public domain)

Published on April 19, 2020 15:44

April 16, 2020

JASON AND THE GOLDEN FLEECE - MORE THAN A MYTH?

The front cover of the issue of Fate Magazine (vol. 42, no. 9, issue #474, September 1989) containing my original article on the possible reality behind the classic Greek legend of Jason and the Golden Fleece (© Fate Magazine – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational and review purposes only)

The front cover of the issue of Fate Magazine (vol. 42, no. 9, issue #474, September 1989) containing my original article on the possible reality behind the classic Greek legend of Jason and the Golden Fleece (© Fate Magazine – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational and review purposes only)One of my very first articles published by Fate Magazine concerned the exciting possibility that the classic Greek legend of the hero Jason and his epic quest aboard his ship the Argo for the magical Golden Fleece at Colchis may have been based at least to a degree upon reality, especially with regard to the Fleece itself. It appeared in the September 1989 issue of Fate, whose front cover, depicting this famous story, opens the present ShukerNature article. Eight years later, my article was republished in my compendium book From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings(1997), containing an extensive selection of my Fate articles. Now, 23 years on again, and this time expanded and partly rewritten, my investigation of Jason and the Golden Fleece finally makes its long-awaited debut on ShukerNature.

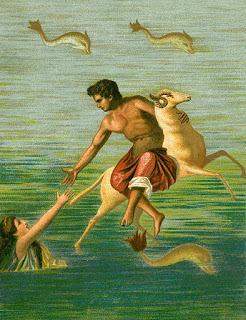

The grim shadow of a raised sword fell across the pale, tensed body of Prince Phryxus as he lay upon the sacrificial slab, awaiting certain death at the hand of his own father, King Athamas of Orchomenus. This city in ancient Greece had once been rich and prosperous, but that year its crop of corn had failed, and its people were starving. Due to a false prophecy originating from Queen Ino, Phryxus's wicked stepmother who hated him, Athamas mistakenly believed that his city's crop failure was a curse inflicted by the gods and could only be lifted by the sacrifice to them of his beloved son, Phryxus. Happily, however, Ino's evil plan was known to the gods, who chose to thwart it in a most spectacular manner.

Phryxus striving to hold on to Helle as she falls from Chrysomallus's back into the sea - depicted in an ancient Roman fresco, 45-79 AD, Pompeii (© Stefano Bolognini/Wikipedia, copyright-free for private or commercial use when copyright owner is attributed)

Phryxus striving to hold on to Helle as she falls from Chrysomallus's back into the sea - depicted in an ancient Roman fresco, 45-79 AD, Pompeii (© Stefano Bolognini/Wikipedia, copyright-free for private or commercial use when copyright owner is attributed)Suddenly, as Athamas's sword was poised to strike the fatal blow that would slay Phryxus, a golden stream of light poured forth from the clouds directly overhead. The king and the gathered congregation of spectators stared up in surprise, and as they did so the clouds parted and a magnificent winged ram with a shimmering fleece of pure gold appeared. The ram was Chrysomallus, sent by the messenger god Hermes to rescue the boy prince. As soon as Chrysomallus alighted on the ground, Phryxus ran to him and sat astride his broad woolly back. So too did Phryxus's young sister, Helle, whom Ino also hated.

Moments later, like a brilliant golden meteor, Chrysomallus was soaring speedily through the sky, journeying eastwards. Just as they were flying over the narrow stretch of sea dividing Europe and Asia, however, Helle looked down, and became so giddy that she fell off Chrysomallus's back, plummeting into the waves where she drowned. From then on, this sea was called the Hellespont. Chrysomallus, meanwhile, flew onwards with Phryxus until they reached the land of Colchis, in what is today the republic of Georgia. There, Phryxus was welcomed by Aeëtes, king of Colchis, but Chrysomallus died, and his glorious golden fleece was hung in a sacred grove, guarded by a dragon. Many years later, the fleece would be the focus of an epic quest by a Greek prince called Jason and his bold crew, the Argonauts, sailing from Iolcus to Colchis via the Black Sea aboard their famous ship the Argo, and assisted by Aeëtes's own daughter Medea in their successful bid to steal the fleece, sailing back to Iolcus with it afterwards.

Children's book illustration from 1902 or earlier, depicting Phryxus and Helle, based upon the above-reproduced Pompeii fresco (public domain)

Children's book illustration from 1902 or earlier, depicting Phryxus and Helle, based upon the above-reproduced Pompeii fresco (public domain)Down through the ages, many ideas have been aired with regard to the Golden Fleece not having been a literal, physical sheep fleece of any kind, but rather a metaphor or a figurative description for something else entirely. Suggestions have included such diverse options as royal power, a book on alchemy, a technique of writing in gold on parchment, the forgiveness of the Gods, a rain cloud, a land of golden corn, the spring-hero, the sea reflecting the sun, the gilded prow of Phryxus's ship, the riches imported from the East, the wealth of technology of Colchis (see later here), a covering for a cult image of Zeus in the form of a ram, a fabric woven from sea silk, and a symbol representing the trading of fleeces dyed with the valuable, highly-prized pigment Tyrian purple (procured from the purple dye murex Bolinus brandaris, and various related species) for Georgian gold. Each of these, and more, has its own supporters, but none has achieved a consensus of scholarly acceptance.

Moreover, most people assume that this entire story is nothing more than a fanciful Greek myth anyway, dating back 3000 years but with no basis in fact. Quite apart from the ostensible fairytale aspect of a golden-fleeced ram, there was no firm evidence to suggest that Greek ships could even have reached the Black Sea prior to the 7th Century BC, when they are known to have colonised this region. However, not everyone has dismissed the legend quite so readily.

Purple dye murex Bolinus brandaris (public domain)

Purple dye murex Bolinus brandaris (public domain)In May 1984, a classics scholar called Tim Severin and a team of modern-day Argonauts set out aboard their own Argo, sailing from Volos (site of Iolcus) in Thessaly, Greece, to Vani (site of Colchis) in western Georgia. Their goal was to recreate Jason's alleged voyage - and thus prove that such a journey could truly have taken place in those far-off days. In order to achieve as intimate a degree of verisimilitude as possible, Severin's specially-designed Argo was patterned on ancient Aegean vessels by naval architect Colin Mudie. It was then built by Greek shipwright Vasilis Delimitros, who crafted it from the same Aleppo pine used by Bronze Age Greek seafarers. When complete, it measured 54 ft in length.

Spanning 1500 nautical miles from the Aegean Sea through the Dardanelles (Hellespont), the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and thence along the Black Sea's Turkish perimeter to his Georgian destination at its eastern limit, Severin's voyage in this new Argo took three months. It was often arduous, but it was also successful - thereby indicating that Jason and the Argonauts' epic journey aboard the Argo was indeed possible even back in those bygone times of ancient Greece. Moreover, as revealed in his fascinating book The Jason Voyage (1986), Severin also learned some interesting items of information relevant to the Golden Fleece.

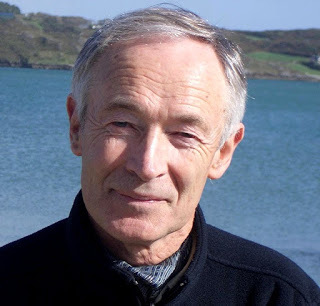

Tim Severin (© Aaron D Linderman/Wikipedia - GNU Free Documentation Licence)

Tim Severin (© Aaron D Linderman/Wikipedia - GNU Free Documentation Licence)This legend is very popular in Georgia even today - where it is taught in schools, and even commemorated in product names, such as a 'Golden Fleece' brand of cigarettes. In addition, western Georgia once harboured a thriving cult of ram worshippers that lasted from the middle Bronze Age into the modern era - as confirmed by such archaeological finds as a bronze ram's head totem dating from the 18th Century BC, and ram's head bracelets moulded from gold that date from the 4th Century BC. There is even an old Georgian folktale of a golden ram tethered by a golden chain in a mountain cave filled with golden treasure.

Severin also learned that the traditional method of prospecting for gold in Georgia, a method dating back countless centuries, is to anchor in a gold-rich stream bed the fleece of a sheep - because the fleece's wool is very effective at trapping particles of gold. After it has been left in the stream for a time, the result will be a fleece impregnated with gold - in other words, a golden fleece! True, it will hardly compare to its magnificent legendary counterpart, but it may have been sufficient to inspire such a legend long ago.

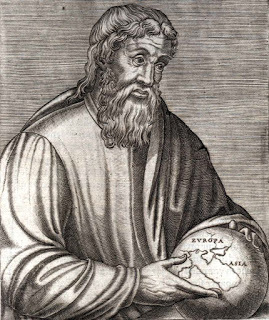

Two Georgian gold coins commemorating the Golden Fleece legend (public domain)

Two Georgian gold coins commemorating the Golden Fleece legend (public domain)The possibility that this activity is the origin of the Golden Fleece account is certainly intriguing, but it is not a recent revelation. As far back in time as the 1st Century BC, the Greek geographer/historian Strabo had made the same suggestion. He suggested that it may have been an ordinary fleece that had been used to trap gold washed down the River Phasis. Particles of gold would have remained ensnared among its fibres, resulting in a fleece that at least upon casual observation might well have appeared to be composed of gold-bearing wool. Although a most ingenious idea, it is surely unlikely that such a superficially deceptive artefact could not only have retained its illusion intact during inevitable closer examination but also have become sufficiently famous to engender one of Greek mythology's most enduring legends.

Dr George Hartwig mentioned in The Subterranean World (1875) that modern-day gold prospectors still use sheep fleeces for this purpose in several different gold-bearing countries. However, he also noted that this was not taken by many authorities as proof that the Golden Fleece was itself a fleece with gold-ensnared fibres. On the contrary, many felt that the quest by Jason and his Argonauts to Colchis was not for a Golden Fleece at all, but for this wealthy city's gold itself, with the fleece being nothing more than a means of obtaining such gold and having no significance of its own. In short, the Golden Fleece's present-day prominence in mythology might be due to erroneous telling and retelling of the ancient myths down through the ages, with the object of Jason's quest (the gold of Colchis) becoming confused with the means of obtaining it (an ordinary sheep fleece).

Strabo – 19th-Century engraving (public domain)

Strabo – 19th-Century engraving (public domain)Although both of these theories are undoubtedly compelling in their simplicity, they are not the only explanations on offer for the origin of the Golden Fleece legend. Another solution, offered by several different researchers, is one that seeks to explain the Golden Fleece in a very different manner - as a misinterpreted and/or mythified reference to fine-wooled fleeces. There are three principal classes of wool:

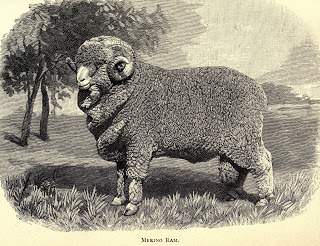

1) Carpet wool (very coarse, and hair-like; used for making carpets and rugs).2) Cross-bred wool (familiar, weaving-quality; produced by the majority of British sheep breeds).3) Fine wool (valuable and lustrous, with exceedingly fine fibres lacking a central medulla; generally obtained today from Merino sheep).

Vintage illustration of a Merino ram (public domain)

Vintage illustration of a Merino ram (public domain)In a paper published by the British scientific journal Nature on 13 April 1973, Dr M.L. Ryder and Dr J.W. Hedges from the ARC Animal Breeding Research Organisation at Edinburgh, Scotland, noted that the legend of the Golden Fleece may actually refer to fine wool. Moreover, in their paper they documented a sample of cloth composed of fine wool that was obtained from a Scythian tomb in the Crimea, and which dated back to the 5th Century BC. If their reconciliation of the Golden Fleece legend with fine wool is correct, this Scythian sample is thus of particular significance. Its age and Crimean locality collectively confirm that fine wool was indeed associated with the Black Sea region, and at a time near that of the Golden Fleece's appearance and Jason's quest for it.

Nevertheless, in 1932 a paper had already appeared in the Proceedings of the Royal Society (of London) that was destined during the 1980s to suggest a much more literal solution to the Golden Fleece mystery than a gold-bearing artefact, a substitute for gold itself, or a mythification of early fine-woolled sheep.

Jason with the Golden Fleece, depicted upon a tin-glazed earthenware plate created in c.1540 AD (public domain)

Jason with the Golden Fleece, depicted upon a tin-glazed earthenware plate created in c.1540 AD (public domain)The paper in question was written by Drs Claude Rimington and A.M. Stewart of the Wool Industries Research Association of Leeds, in West Yorkshire, England, and concerned itself with a previously uninvestigated pigment. Raw wool comprises the wool fibres and 'yolk'. This latter component in turn consists of ether-soluble grease (secreted by the sheep's sebaceous skin glands), and a water-soluble substance known as suint (secreted by the sheep's sweat glands). In their paper, Rimington and Stewart recorded that a golden-brown colouration existed in varying intensities within the suint of certain sheep, its intensity of colour depending upon the animals' diet and age, and also influenced by conditions stimulating sweat.

Following their analysis of the composition and secretion of this mysterious pigment (which they termed lanaurin - meaning 'golden wool'), Rimington and Stewart concluded that it was a pyrrolic complex. That is to say, a compound whose chemical structure is based upon a ring of four carbon atoms and one nitrogen atom. Moreover, they believed it to be related to the bile pigment bilirubin - a reddish substance originating via the breakdown of the well-known respiratory pigment haemoglobin, and normally secreted into the bile by the liver in many mammalian species.

Modern-day sculpture of the Golden Fleece hanging in its sacred grove and protected by a dragon, on display at Sochi in Russia (public domain)

Modern-day sculpture of the Golden Fleece hanging in its sacred grove and protected by a dragon, on display at Sochi in Russia (public domain)Rimington and Stewart suggested that the appearance of lanaurin resulted from an enhanced destruction of haemoglobin within the sheep so afflicted; they also confirmed that it was conveyed through the skin of such sheep into their wool via the sweat glands. Furthermore, not only did this compound occur within the woolof golden-coloured sheep, it was also found within their urine, which in turn was excessively pigmented. Comparisons were drawn between golden-woolled sheep and inherited acholuric jaundice in humans, with the suggestion that as with this type of human jaundice, the golden-wool condition in sheep may be genetically based.

Further researches into this intriguing area of biochemistry took place in the years to come. Chemical analyses became more precise, and chemical nomenclature diversified - substances inducing jaundice becoming known as icterogenic agents. By the early 1960s, examples of abnormal golden colouration had been reported and studied not only in sheep but also in rabbits (see the series of papers by Rimington and colleagues published during this period in the Royal Society's Proceedings), and it emerged that a number of natural and synthetic icterogenic agents belonged to a group of chemicals known as the pentacyclic triterpenoids. In other words, they are organic compounds produced in animals and also plants by combination into larger molecules of units each containing five carbon atoms arranged in the characteristic pattern present in isoprene (a simple-structured substance used in the manufacture of rubber).

'The Golden Fleece' by Herbert James Draper, 1904, oil on canvas (public domain)

'The Golden Fleece' by Herbert James Draper, 1904, oil on canvas (public domain)By 1963 and in partnership with J.M.M. Brown and Barbara Sawyer, Rimington's continuing researches in this field had uncovered some important new information. They revealed that the golden-wool condition in sheep could also be induced by environmental means - namely, the ingestion by sheep of leaves from certain plants (especially shrubs of the genus Lantana). These plants contained pentacyclic triterpenoids that poisoned the liver of such sheep, thus preventing the normal excretion of bilirubin into the bile - resulting instead in its passage (together with that of various related pigments) into the skin and wool suint of those animals, thereby bestowing upon their wool the golden appearance reported in Rimington's earlier studies.

So here we have an environmentally-stimulated phenomenon that produces sheep (and rabbits!) with golden-coloured wool. Not surprisingly, therefore, it was only a matter of time before this circumstance was mooted as the solution to the fabled Golden Fleece itself. And in a letter to Naturepublished on 23 June 1987, this was indeed proposed in that context by Dr J. Smith, a researcher in physical chemistry at Melbourne University, Australia.

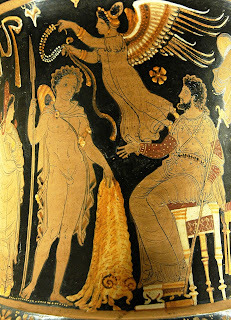

Jason bringing Pelias the Golden Fleece and a winged victory prepares to crown him with a wreath - Side A from an Apulian red-figure calyx crater, in the Louvre, Paris (public domain)

Jason bringing Pelias the Golden Fleece and a winged victory prepares to crown him with a wreath - Side A from an Apulian red-figure calyx crater, in the Louvre, Paris (public domain)In his letter, Dr Smith recalled an earlier portion of the Golden Fleece legend. Namely, the section in which its ovine bearer appeared during a period of severe famine in Greece, having been sent by Hermes to rescue two children due to be sacrificed by their evil stepmother Ino, in an attempt to appease the gods and thereby end the famine. Smith noted that during modern-day periods of famine in New Zealand, sheep there were often fed upon leaves from trees by their distraught farmer owners. He then postulated that under similar conditions in Greece, farmers may well have fed their sheep upon leaves from the extensively cultivated olive tree Olea europea. And it just so happens that the olive tree's leaves contain great amounts of oleanolic acid, which is the basic substance from which the known icterogenic pentacyclic triterpenoids are derived.

Tests carried out with rabbits by Brown, Rimington and Sawyer in the 1960s had readily revealed that small amounts of oleanolic acid did not induce any icterogenic activity. Conversely, as argued by Smith, when present in much greater concentrations - as in the leaves of the olive tree (and particularly in those subjected to draught stress, as experienced in famine conditions) - oleanolic acid could exert a deleterious effect upon the liver of sheep, and in turn bring about abnormal golden discolouration of wool. In short, the Golden Fleece legend may have been based upon sightings of sheep that, during the famine periods experienced by Greece in earlier days, had been fed upon olive tree leaves, whose high triterpenoid content had ultimately caused their fleeces to be stained with golden bile pigments.

A 5,000-year-old European olive tree (© Mujaddara/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

A 5,000-year-old European olive tree (© Mujaddara/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)Although, as Smith himself admitted, this is all speculative, there is no doubt that it offers an exceedingly beguiling solution to the legend - and one, moreover, that actually corresponds very closely not just with its principal but also with its more peripheral portions.

At the same time, however, some contrary evidence also exists – which was brought to attention via a follow-up letter published in Nature on 5 November 1987 and written by research chemists Drs Patrick Moyna and Horacio Heinzen from the Faculty of Chemistry in Uruguay's Universidad de la Republica. They reported that oleanolic acid is contained in even greater concentrations in certain other plant sources - for example, it accounts for up to 50% of the content of grapes' epicuticular wax. Yet this does not appear to have any toxic effect upon humans consuming the grapes - in contrast to the outcome that one would have predicted, judging from the arguments offered with sheep and olive leaves. However, Moyna and Heinzen did not provide any references in relation to sheep and grapes, and it is well known that the gastrointestinal tract and its associated organs in humans differ very considerably in morphology and physiology from those of sheep.

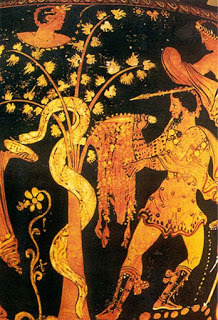

The Golden Fleece, depicted upon an ancient Greek vase (public domain)

The Golden Fleece, depicted upon an ancient Greek vase (public domain)The concept of liver-damaged sheep with discoloured yellowish wool stained by bile pigments certainly fails to conjure forth the romantic image evoked by the stirring legend of the Golden Fleece. However, the prosaic practicality of science is rarely able to match the imaginative wonder of illusory fable and fairytale.

In March 1991, yet another theory was highlighted, again by Dr ML. Ryder. In an Oxford Journal of Archaeology paper, he discussed evidence not only for the two afore-chronicled theories concerning fine wool and the using of fleeces to collect gold from water, but also for the possibility that the legend stemmed at least in part from fleeces sporting genetically-induced tan-coloured fibres rather than white ones. Clearly, the allure and intrigue of the Golden Fleece is as much alive in modern times as it was 3000 years ago in ancient times. Not bad for a mere myth…?

The Colchis princess Medea, the Golden Fleece, and its dragon guardian – plate from an old Russian children's book (public domain)

The Colchis princess Medea, the Golden Fleece, and its dragon guardian – plate from an old Russian children's book (public domain)A final scientific curiosity linking sheep and gold that is well worth mentioning here is the occurrence of reports from many parts of the world down through the years concerning sheep that supposedly possess teeth plated with gold! These still appear spasmodically in the media even today, yet as far back as 25 August 1920 in a paper published by the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, Thomas Steel revealed that the golden colour was due merely to the reflection of light from the overlapping of thin films of encrusting tartar, deposited on the teeth by the animals' own saliva. As for the tartar - far from being gold, or even iron pyrites ('fool's gold'), this had been conclusively shown to be nothing more exciting (or valuable!) than impure calcium phosphate and organic matter. In Crete, it is widely believed that sheep there sporting golden teeth have been eating the herb nevrida Polygonum ideaum over a lengthy period of time, as investigated in an online article here that contains photographs of gold-stained sheep teeth.

It was Shakespeare who said: "All that glisters is not gold", and judging from the subjects investigated in this article, he certainly had a point!

Erasmus Quellinus II – 'Jason with the Golden Fleece', 1630 (public domain)

Erasmus Quellinus II – 'Jason with the Golden Fleece', 1630 (public domain)

Published on April 16, 2020 05:56

April 14, 2020

INTRODUCING THE KISUALA - MISSING IN MADAGASCAR?

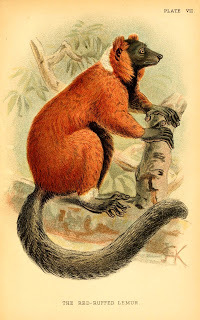

Exquisite illustration of the red ruffed lemur Varecia rubra, in A Hand-Book to the Primates, Plate VII, 1894 (public domain)

Exquisite illustration of the red ruffed lemur Varecia rubra, in A Hand-Book to the Primates, Plate VII, 1894 (public domain)Despite being officially deemed to have become extinct several centuries ago at the very least, the possibility that some of Madagascar's giant lemurs persisted into modern times and may still be doing so today has always fascinated me, ever since as a teenager back in the early 1970s I first read the famous chapter devoted to this island mini-continent's mystery beasts in Dr Bernard Heuvelmans's classic cryptozoology book On the Track of Unknown Animals. The most celebrated Madagascan cryptids that may be late-surviving giant lemurs include the tratratratra, kidoky, tokandia, habéby, mangarsahoc, kalanoro, and kotoko (see my book Mirabilis for extensive coverage).

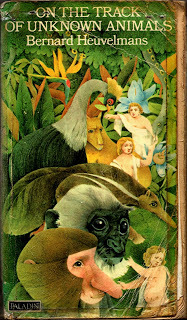

My much-read, greatly-treasured, massively-influential copy of the 1972 abridged Paladin Books paperback edition of On the Track of Unknown Animals (© Dr Karl Shuker/Paladin)

My much-read, greatly-treasured, massively-influential copy of the 1972 abridged Paladin Books paperback edition of On the Track of Unknown Animals (© Dr Karl Shuker/Paladin)On 5 November 2018, however, the American TV documentary channel Animal Planet posted on YouTube a video in which wildlife adventurer Forrest Galante was seeking a mystery lemur that I had never seen documented anywhere before (click here to access the video).

Forrest Galante (© Mitchell J. Long/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Forrest Galante (© Mitchell J. Long/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)The locals describe it as a giant red lemur, and refer to it as the kisuala. In the video's description, the question is posed as to whether this cryptid may be a surviving species of Pachylemur- a two-species genus of extinct giant lemur that may have survived until at least as recently as 500 years ago.

Life restoration of Pachylemur insignis, based upon a photograph of a skull, a photograph of a skeleton, restoration by Stephen Nash, and correspondence with Dr Laurie Godfrey (© Smokeybjb/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)

Life restoration of Pachylemur insignis, based upon a photograph of a skull, a photograph of a skeleton, restoration by Stephen Nash, and correspondence with Dr Laurie Godfrey (© Smokeybjb/Wikipedia –

CC BY-SA 3.0 licence

)They are known colloquially as giant ruffed lemurs, because they were most closely related to the somewhat smaller but still-living Varecia ruffed lemurs. One of these, the red ruffed lemur Varecia rubra, does indeed have predominantly – and very prominently – red fur,

The aptly-named red ruffed lemur (Mathias Appel/Wikipedia – copyright-free)

The aptly-named red ruffed lemur (Mathias Appel/Wikipedia – copyright-free)I don't think that I'm including a spoiler for viewers about to watch the video by saying that Forrest's search for the kisuala was unsuccessful – after all, had it been successful it would have made major headlines worldwide. However, it is always exciting to publicise a cryptid not previously documented within the cryptozoological literature, and we can but hope that future searches for this intriguing animal will be made.

The black-and-white ruffed lemur V. variegata, closely related to V. rubra – indeed, until 2001 they were treated merely as subspecies of a single species of ruffed lemur, but they exhibit sufficient genetic differences to warrant being elevated to full species in their own right (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The black-and-white ruffed lemur V. variegata, closely related to V. rubra – indeed, until 2001 they were treated merely as subspecies of a single species of ruffed lemur, but they exhibit sufficient genetic differences to warrant being elevated to full species in their own right (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on April 14, 2020 18:41

April 13, 2020

COCK-A-HOOP OVER A COCKATOO – A SHUKERNATURE PICTURE OF THE DAY

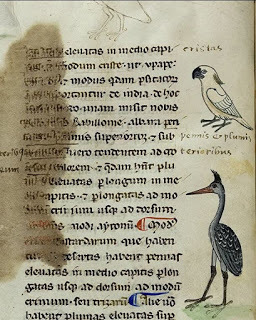

One of the four colour sketches of the cockatoo owned by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Sicily and contained in his book De Arte Venandi cum Avibus, dating from the mid-13thCentury AD (public domain / Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

One of the four colour sketches of the cockatoo owned by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Sicily and contained in his book De Arte Venandi cum Avibus, dating from the mid-13thCentury AD (public domain / Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)It's been a while since ShukerNature featured a Picture of the Day, but the one presented above is greatly deserving of that accolade, and here's why.

History scholars have long known that sometime between 1217 and 1238 AD, al-Malik Muhammad al-Kamil, the fourth Ayyubid sultan of Egypt, gave as a gift to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Sicily a mysterious white parrot. However, the taxonomic identity of this latter bird had always remained controversial – until June 2018.

For that was when, via a paper published by the journal Parergon, Melbourne University researcher Dr Heather Dalton and a team of Finnish scholars revealed that while studying a Latin-language falconry book entitled De Arte Venandi cum Avibus ('The Art of Hunting with Birds') dating from the 1240s that had been written by Frederick II and contained over 900 pictures of animals maintained by him in his palaces, they discovered that it included no fewer than four colour sketches (plus a written description) of his enigmatic white parrot.

A sulphur-crested cockatoo (© Donald Hobern/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)

A sulphur-crested cockatoo (© Donald Hobern/Wikipedia –

CC BY 2.0 licence

)These sketches conclusively identified it as a female sulphur-crested cockatoo Cacatua galerita - it was painted with red eyes, like females of this species, whereas males have black eyes. Moreover, some specimens, particularly females, have much paler crests than others – not all have the striking golden-shaded crest that characterises their species.

Split into several geographically-discrete subspecies, Cacatua galerita is native to northern Australia, New Guinea, and certain Indonesian islands. Consequently, not only do these images constitute the earliest-known European depictions of a cockatoo, pre-dating by 250 years the previous holder of this record (an altarpiece artwork by Italian painter Andrea Mantegna dating from 1496 and entitled 'Madonna della Vittoria'), but also they provide proof of merchant trading between northern Australia and the Middle East, from whence exotic items would in turn be imported into Europe.

Frederick II's falconry book is housed in the Vatican Library.

Two more illustrations of Frederick II's cockatoo from

De Arte Venandi cum Avibus

(public domain / Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Two more illustrations of Frederick II's cockatoo from

De Arte Venandi cum Avibus

(public domain / Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational/review purposes only)

Published on April 13, 2020 18:22

April 11, 2020

JUNGLE WALRUSES, A PERPLEXING PETROGLYPH, AND AN AQUATIC SABRE-TOOTH WITH SCALES? INVESTIGATING A LITTLE-KNOWN CRYPTOZOOLOGICAL CONUNDRUM

The baffling Bushman rock painting at Brackfontein Ridge, in South Africa's Orange Free State, that depicts an unexpectedly walrus-like mystery beast (public domain)

The baffling Bushman rock painting at Brackfontein Ridge, in South Africa's Orange Free State, that depicts an unexpectedly walrus-like mystery beast (public domain)Adam Thorn from Perth in Western Australia is a famous animal adventurer, jungle explorer, and co-host of the History Channel's very popular 'Kings of Pain' show. He is also a longstanding Facebook friend of mine, and shares my interest in mysterious, unidentified creatures, especially an extremely curious African cryptid referred to colloquially as the jungle walrus but which is little known even in cryptozoological circles, let alone beyond them, yet is ostensibly represented by a fascinating if perplexing Bushman rock painting (petroglyph). Consequently, please allow me to present for the first time here on ShukerNature a comprehensive survey of this and other tusk-touting aquatic anomalies that have been reported down through the ages from several different regions of sub-Saharan Africa, and which also feature in my newest book (#32), to be published later this year. Hoping that you enjoy it, Adam – and everyone else too!

Many years ago, a pygmy from the Democratic Republic of the Congo's Ituri Forest (where Sir Harry Johnston famously discovered the okapi in 1901) identified a picture of a walrus shown to him by aptly-named big-game hunter John A. Hunter as a savage, nocturnal beast that lived in the deepest parts of the forest. Not surprisingly, Hunter dismissed this claim of a 'jungle walrus' as nothing more than the pygmy's desire to please him, as he noted in his book Hunter (1952).

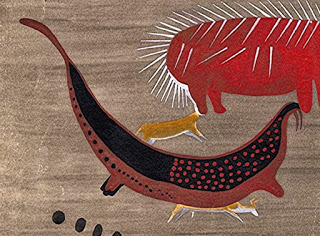

As will be seen here, however, it may be prudent not to dismiss entirely the pygmy's claim, because a startling number of such creatures, all sharing a fundamental similarity of form, lifestyle, and habitat, are documented within the chronicles of cryptozoology – not least of which is a certain highly enigmatic rock painting discovered at Brackfontein Ridge in South Africa's Orange Free State. How old this native Bushman artwork is, whether it dates back a mere couple of centuries or is possibly significantly older, remains debatable, but even more so is what it depicts.

George William Stow (public domain)

George William Stow (public domain)It first attracted attention in 1930, when it was depicted in Rock-Paintings in South Africa, a sumptuous work by George William Stow and Dorothea F. Bleek. The text of this book was written by anthropologist Bleek to accompany its numerous full-page illustrations that consisted of meticulous, often full-colour copies of South African petroglyphs that had been prepared between 1867 and 1882 by Stow (1822-1882), an English-born trader, historian, and geologist, who had been passionately interested in South African native races, especially the Bushmen. His travels as a trader had taken him to many little-visited South African localities containing petroglyphs, and his interest in them had led him to prepare his copies – which proved very valuable, because some of the originals no longer exist, have subsequently become damaged or worn, or are in quite inaccessible sites.

According to Bleek, the location of the particular petroglyph under consideration here in this ShukerNature article was a cave in Brackfontein Ridge, situated on an Orange Free State farm named La Belle France that was owned back then by a Mr Connor Swanepool, and its subject was one of several strange animals portrayed together there. As now seen, this remarkable petroglyph portrays an animal that bears a startling resemblance to a walrus - from its rounded head displaying two very large downward-curving tusks to its elongated, tapering body and paddle-like limbs. Indeed, its only prominent difference from the latter pinniped is that it possesses a long tail, whereas during 23 million years of evolution from original terrestrial ancestors the walrus has lost its tail (but see later for a putative explanation of this morphological distinction). No satisfactory mainstream zoological identification of this petroglyph-portrayed walrus lookalike has been proffered so far, nor of the other equally odd animals depicted alongside it – Bleek deemed them to be mythical beasts - but several very comparable cryptozoological counterparts have been reported across tropical Africa, and all of them are claimed in eyewitness testimonies to be predominantly aquatic.

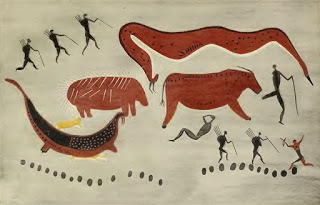

Stow's copy of the collection of petroglyphs at Brackfontein that includes the jungle walrus (public domain)

Stow's copy of the collection of petroglyphs at Brackfontein that includes the jungle walrus (public domain)The marked predominance of this feature is acknowledged in the various native names given to these 'jungle walruses' by different native peoples. In the Central African Republic (CAR), for instance, the Banda speak of the mourou n'gou or muru-ngu (meaning 'water leopard'); the Baya speak of the dilali ('water lion'); the Sangho of the ze-ti-ngu or nze ti gou ('water panther'); and the Zande of the mamaimé ('water lion') or (just to be different) ngoroli ('water elephant'). Judging from all but the last-mentioned term, these creatures are quite clearly feline, an assumption supported by the various descriptions of them on record.

According to an old Banda tribesman called Moussa, interviewed in 1934 by Lucien Blancou (formerly Chief Game Inspector in what was then French Equatorial Africa - subsequently split into Chad, the CAR, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon), the mourou n'gou was somewhat larger than a lion in size (Moussa estimating its length at about 12 ft), with an overall body shape and pelage background colour reminiscent of a leopard's, but additionally adorned with stripes. Curiously, its paw-print was described as "containing a circle in the middle".

Apparently, Moussa at some stage had observed one of these creatures emerging from the Koukourou river in close proximity to a soldier in a canoe. The mourou n'gou seized the hapless man and dragged him down into the water. As a result of this incident, the detachment to which the beast's victim had belonged decided not to cross the river at this point thereafter but instead at a new location some considerable distance to the east In 1945, a native gunbearer called Mitikata drew a sketch of the mourou n'gou, which showed a small-headed, large-fanged creature about 8 ft long, with a plump, uniformly brown-coloured body and a panther-like tail.

Intriguingly, the Banda also use the name 'mourou ngou' to signify a very different, known species – central Africa's giant otter shrew Potamogale velox. Its English name derives from its deceptively otter-like outward appearance and its former classification as a relative of shrews within the taxonomic order Insectivora (but more recently it has been reclassified as a member of the exclusively African taxonomic order Afrosoricida, alongside tenrecs and golden moles). Like real otters, it lives an aquatic, piscivorous existence, but has a head-and-body length of only about 1 ft plus a slightly shorter tail, yielding a total size that is not only much smaller than that of real otters but also very much smaller than estimates for the mourou ngou. Nor does its uniformly unpatterned, brown fur dorsally and paler ventrally resemble in any way the prominently striped or spotted coat of the latter cryptid, whereas any suggestion of large fangs is conspicuous only by its absence in relation to the giant otter shrew. Clearly, therefore, whatever the cryptozoological mourou ngou may be if it truly exists, it is certainly not the giant otter shrew.

Painting of giant otter shrew, from the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1869 (public domain)

Painting of giant otter shrew, from the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1869 (public domain)During December 1994-January 1995, Belgian cryptozoologist Eric Joye led a two-man expedition, dubbed 'Operation Mourou N'gou', in search of this elusive creature. Although they failed to spy it themselves, Joye and his team-mate, hunting guide Willy Blomme, succeeded in gathering some very interesting anecdotal evidence - probably the most extensive obtained since the material collected here during the 1930s by Lucien Blancou (Cryptozoologia, September 1994, September 1996).

Claiming to have narrowly avoided being propelled into the Bamingui River by such an animal as he sat fishing at the river's edge one afternoon in February 1985, a native guide called Marcel told Joye that the mourou n'gou hunts in pairs - one waiting in the river to seize any prey chased into the water by the other. According to Marcel, the mourou n'gou compares with a leopard in shape and size, and its pelage is ochre, dappled with blue and white spots that are very distinct upon its back but less well-defined upon its flanks. It has a long tail, hairier than the leopard's, and its head is said to be a little like that of a civet (does this mean that, like a civet, it has a dark face mask?), but its teeth are very large and resemble those of a Big Cat such as the leopard or lion. Marcel followed the mourou n'gou's trail, which was like a leopard's but bigger. Also, when it runs, it leaves behind the impression of claws, which is not usual for a leopard.

A second so-called water leopard is the nzemendim, spoken of by the natives in the N'velle distinct of Yaounde, Cameroon, and documented in Gorillas Were My Neighbours (1956), written by Fred G. Merfield and Harry Miller. The locals claimed that it was a type of leopard that lived in small rivers, and frequently carried off women and children. After several failed attempts to spot this dangerous mystery beast, one of this book's authors believes that he finally achieved success:

One morning, just as it was getting light, an animal swam rapidly upstream and landed on the opposite bank. The light was still poor, and all I could see was something furry, spotted and four-legged, so I fired. The animal spun round and dived back into the water. I thought it was lost, but when the sun rose and my men turned up, we found it dead and washed ashore a few hundred yards downstream. It was a big dog-otter, a very old fellow whose fur had gone grey and blotchy, giving the appearance of spots. The natives would not admit that this was their nzemendim, and having no more time to spare I gave up and went home.

Could some 'jungle walruses' be extra-large specimens of otter? Standing alongside a statue of a giant otter in South Africa's Kirstenbosch Gardens (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Could some 'jungle walruses' be extra-large specimens of otter? Standing alongside a statue of a giant otter in South Africa's Kirstenbosch Gardens (© Dr Karl Shuker)Lucien Blancou learnt a little concerning another type of supposed aquatic mystery cat, the dilali. According to an interpreter at Bozoum in eastern Ubangi-Shari (a French colony that was part of what was then French Equatorial Africa), it possessed the body of a horse and the claws of a lion, as well as large walrus-like tusks (this last-noted feature was mentioned to Blancou by a Zande native guard).

Then there is the nze ti gou, a nocturnal beast of leopard stature, having red fur marked with pale stripes or spots, living within hollows in large rivers, and emitting a thunderous noise. Such creatures are not restricted to the CAR and Cameroon either.

The Mbunda tribe of eastern Angola speak of the coje ya menia ('water lion'), which attracted the interest of Ilse von Nolde during her sojourn there in the early 1930s, and which she subsequently wrote about in an article published by the periodical Deutsche Kolonialzeitungin 1939. Like the nze ti gou, this beast is well known to the natives for its loud rumbling vocals, and, although principally aquatic, sometimes ventures forth onto dry land. Like the other beasts mentioned here, it too is armed with large canine teeth or tusks, and supposedly kills hippopotamuses with them, despite its own smaller body size. The observations and dealings of von Nolde with this region's natives convinced her that the coje ya menia was not based upon misidentified sightings of crocodiles or hippos, or of these species' spoor. On the contrary, the natives were very adept at identifying and interpreting spoor.

Reconstruction of coje ya menia attacking hippopotamus, by Wilhelm Eigener (public domain)

Reconstruction of coje ya menia attacking hippopotamus, by Wilhelm Eigener (public domain)She was equally convinced of the sincerity of a Portuguese lorry driver who told her that in the company of some natives, he had actually tracked a coje ya menia that had chased after and killed a hippopotamus. Sure enough, the tracks of the two beasts had led to the mutilated carcase of a hippo - yet no part of it had been eaten. The tracks of the coje ya menia were smaller than those of the hippo, and although somewhat reminiscent of an elephant's in shape, they additionally contained the impression of toes. Worth noting here is that as far back as 1947 in a Kosmos article, renowned German cryptozoologist Dr Ingo Krumbiegel had suggested a surviving sabre-tooth as a possible identity for this Löwe des Wassers ('water lion').

Also worth keeping in mind is a certain Ngona Horn folktale of the Wahungwe people from Zimbabwe, documented in African Genesis (1983) by Prof. Leo Frobenius and Douglas Fox. For it refers to some very odd felids - "lions under the water", and is itself entitled 'The Water Lions'. Could these be comparable with nearby Angola's coje ya menia?

The Zande or Azande is a native African tribe indigenous to the northeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Republic of South Sudan, and the southeastern section of the CAR – which in combination is often referred to as Zandeland. The Zande people speak of several mysterious beasts that may possibly be cryptozoological in nature. One of the most intriguing of these is the mamaimé or water leopard – but one that sounds very different from both of the previous two versions. In an article published by the journal Man in September 1963, Oxford anthropologist Prof. E.E. Evans-Pritchard noted that the Zande's water leopard had been described to him by them as follows:

The water leopard is a powerful kind of beast, dark and with a blackish skin and a head of hair shaggy to the neck. Its pads are very large and its palms hairless like those of a man. It has powerful teeth in its mouth. It seizes a person as does a crocodile. It appears in places of deep water. Its eyes are very large and red, like the seeds of the nzua vegetable [like tomatoes]. It lives in holes as crocodiles do, but where it resides there is water and many fish near it. This water never dries up, for it is its home.

Prof. Evans-Pritchard was also told that this strange creature has hair like a man's that falls over its body, and he noted that a Major P.M. Larken had stated in an article published in 1926 that water leopards are said to live in deep pools within large rivers, and that big fissures in the banks of rivers have often been pointed out by locals as being these aquatic cryptids' homes. Evans-Pritchard doubted that the water leopard genuinely existed but was at a loss as to how to explain reports of it.

Moving to the DRC's southern regions, we encounter reports of yet another similar animal, known variously as the simba ya mai, ntambue ya mai, and ntambo wa luy, all of which translate as 'water lion'. Further mystery beasts apparently belonging to this same type include the Kenyan ol-maima and the Sudanese nyo-kodoing.

Could aquatic sabre-tooths exist in remote regions of tropical Africa? (© Randy Merrill)

Could aquatic sabre-tooths exist in remote regions of tropical Africa? (© Randy Merrill)From description and native nomenclature a feline identity seems probable, and from their formidable upper canines an undiscovered modern-day species of sabre-tooth (machairodontid) has been popularly proposed by some cryptozoologists (see below), although the fossil record attests that all African sabre-tooths had vanished before the Pleistocene's close, around 11,000 years ago). Moreover, the existence of an aquatic sabre-tooth is a very bizarre concept. Certainly there is no evidence from fossil finds to suggest that any extinct machairodontid ever became adapted for this particular lifestyle. So is it really possible that such a creature is the explanation for any or all of the various mystery beasts described here?

Following on from Krumbiegel's earlier suggestion, in his books Les Derniers Dragons d'Afrique (1978) and Les Félins Encore Inconnus d'Afrique (2007) veteran French cryptozoologist Dr Bernard Heuvelmans asserted that it was not only possible but was, to his mind, more than likely. The principal arguments that he put forward in support of this can be summarised as follows:

1) Despite popular belief, many cat species are not afraid of water.

2) The very effective utilisation by walruses of their own huge upper canines for anchorage, dragging themselves on to land or ice floes, and ploughing up the sea bed sediment in search of modest-sized prey demonstrates that the sabre-tooth's enlarged canines would be of great benefit for an aquatic existence.

3) Conversely, on land such teeth would surely have been a great handicap to the sabre-tooth when attempting to tear off and devour pieces of meat from its prey.

4) Due to this, sabre-tooths would have faired badly in competition with true felids of comparable size, e.g. lions and leopards, and ultimately may have been forced to move into ecological niches unoccupied by such cats - namely remote mountains and aquatic realms (which just so happen to be the very environments from which reports of alleged modern-day sabre-tooths are emerging – a future ShukerNature article will explore tales of terrestrial, montane sabre-tooth lookalikes).

Les Félins Encore Inconnus d'Afrique

(© L'Oeil du Sphinx – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational and review purposes only)

Les Félins Encore Inconnus d'Afrique

(© L'Oeil du Sphinx – reproduced here on a strictly non-commercial Fair Use basis for educational and review purposes only)Consequently, Heuvelmans believed that sabre-tooths could exist very readily in an aquatic environment simply by paralleling the walrus's lifestyle. Moreover, if challenged by potential rivals such as elephants or hippos, the sabre-tooth would be more than amply equipped to dispose of them, and could even drink the blood spurting from any vanquished opponent's neck (some authorities believe that the fossil terrestrial sabre-tooths were themselves sanguinivorous). Its carcase could serve as a food source too. For if dragged underwater by the sabre-tooth and allowed to decompose, the carcase's meat would eventually soften, enabling it to be torn off in pieces and devoured more readily by the sabre-tooth, thereby cancelling out the problems that the felid might otherwise experience due to its cumbersome canines.

Once again, this suggestion is supported by walrus activity. Some walruses have been reported killing seals and small whales, and lumps of blubber and seal remains (soft and/or from decomposing beached carcases - hence easy to tear) have been found in the stomach of some walruses.

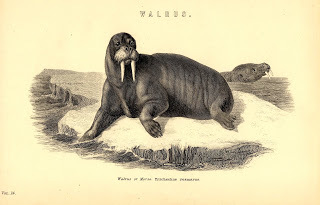

Nor have we come to the end of walrus parallels. Any sabre-tooth modified via evolution for an aquatic existence that compared closely with that of a walrus behaviourally would very likely follow a similar course morphologically too (convergent evolution). Conversely, as the known fossil sabre-tooths of Africa's early Pleistocene (2 million years ago) displayed terrestrial-related morphology, any amphibious development must have occurred since then. Yet it is rather unlikely that as drastic a change as the complete loss of a tail via evolution would have occurred in so short (geologically-speaking) a space of time (as noted earlier, it took 23 million years for today's walruses, lacking a tail, to evolve from their original terrestrial ancestors). Consequently, the Brackfontein Ridge rock painting is precisely what we would expect a recently-evolved amphibious sabre-tooth to look like - a more streamlined version of its terrestrial counterpart with limbs modified for an aquatic life but with the tail not yet lost. Also worth noting is that such a sabre-tooth may be expected to be larger than land-living species, because the accompanying weight increase would be buoyed by its surrounding liquid environment. This would explain the notable size of some of the mystery beasts reported in this article.

Delightful 19th-Century walrus engraving – this is one of the very first engravings that I ever purchased, more than 30 years ago, and it has remained one of my favourites ever since, yet it has never appeared in any of my writings, until now! (public domain)

Delightful 19th-Century walrus engraving – this is one of the very first engravings that I ever purchased, more than 30 years ago, and it has remained one of my favourites ever since, yet it has never appeared in any of my writings, until now! (public domain)Finally, and in the time-honoured tradition of keeping the best (or at least the most bemusing!) to the end, here is what must assuredly be the strangest jungle walrus of all – the Kenyan dingonek. An aquatic beast of generally feline appearance, familiar to the Wa-Ndorobo tribe, and allegedly once shot at by adventurer John Alfred Jordan during the early 20th Century, Kenya's highly elusive but exceedingly daunting dingonek is in the opinion of Heuvelmans another possible member of the aquatic sabre-tooth association. Its fangs are huge; its body is long and as wide as a hippopotamus's; its tail is lengthy and broad, and swings gently against the river current when the animal is in the water; it has four short legs, and its feet are as big as a hippo's, but they bear large claws like those of a crocodile.

True, it possesses one feature that initially seems to exclude it from a felid identity – namely, a body covered in scales. Heuvelmans, however, considered it more likely that these are merely optical illusions produced by light shining upon a particularly reflective pelage, and one that also bears tufts of hair that have adhered together as a result of the animal having been submerged in water, thereby creating the effect of scales. Having said that, in his description of an alleged first-hand encounter with a dingonek in 1905, documented in his book Elephants and Ivory: True Tales of Hunting and Adventure (1956), Jordan seemed very emphatic that this creature was genuinely scaled:

I slid down the bank and got in the cover of the bushes. There it was.

It was in midstream, about thirty feet from me, a beast-fish, a creature from your nightmares. It was fifteen to eighteen feet in length, with a massive head, not a head like a crocodile's, but flat-skulled and round. It had two yellow fangs dropping from its upper jaw, and its back was as broad as a hippo's, but it was scaled in beautifully overlapping plates, as smooth and as intricate as those I've seen on an old Arabian cuirass. The sunlight fell on those wet scales and was dappled by the leaves, and made them seem as brilliantly colored as a leopard's coat. It had something of every animal in it. It was impossible.

There was a broad tail, and this was swinging gently against the current, keeping it midstream, keeping it stationary, whatever it was.

At last I took aim on it...I aimed the .303 at the base of the neck and gave it one solid round.

I saw the bullet hit, and heard it hit the way you do at short range. The beast turned in a great flurry of yellow water until it was facing the bank and my cover. It leaped into the air until it was standing, or so it seemed, its pale belly scales vivid, ten or twelve feet on end.

[Jordan and his native helpers then fled through the forest for 300 yards before halting, but after a time they cautiously returned to the river] It had gone, but its spoor was all over the soft mud, huge prints about the size of a hippo's, but clawed.

Some Wanderobo told me that they knew about this thing, they called it a dingonek. The Kavirondo knew of it too. They had seen more than one of them and made a god out of it whom they called "Luquata." They were worried when they heard that a white man had shot at Lukuata. They said that now they would all die of sleeping sickness, and it is true that there was an epidemic of it among the Kavirondo that year.

Jordan's noting that it was considered bad luck to kill a dingonek echoes a belief that is also prevalent concerning DR Congo's equivalent mystery beast, the ntambo wa luy or simba ya mai, as recorded in Charles Mahauden's book Kisongokimo(1965). Such taboos have undoubtedly assisted in saving these potentially dangerous creatures from extirpation.

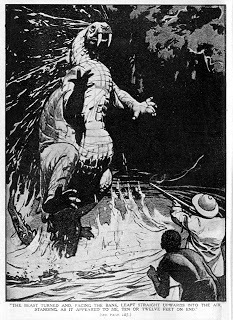

Dingonek illustration based upon Jordan's encounter, Wide World Magazine, 1917 (public domain)

Dingonek illustration based upon Jordan's encounter, Wide World Magazine, 1917 (public domain)At much the same time as Jordan's sighting, another hunter spied a dingonek floating on a log down the Mara River (also running into Lake Victoria) while in high flood - but it quickly slid off and into the water. Near Kenya's Amala River, the Masai call it the ol-maima and sometimes see it lying in the sun on the sand by the riverside - but if disturbed, it slips into the water at once, submerging until only its head remains above the surface.

Jordan also documented his dingonek encounter in his later book, The Elephant Stone (1959), and here he emphasised its fangs and scales:

Fifteen to eighteen feet long, with a massive head shaped like that of an otter, two large fangs, as thick as walrus teeth, descending from the upper jaw; its back as wide as a male hippo's, yet scaled distinctly, like an armadillo; and I could see also why my Lumbwa [native helpers] had spoken of a leopard's body, for the light reflected on the scales in that cat's colours. Idly it switched a broad tail...

In a much earlier account of his dingonek sighting, moreover, given by him to a London Daily Mail newspaper reporter almost 40 years before his own books were published, Jordan specifically stated that this creature's two fangs "were like those of a walrus protruding from its mouth" and that its body "was shaped like a hippopotamus but scaled". However, after stating that he fired at it, Jordan then claimed: "My further observations were cut short by the animal charging us", and went on to say that he returned to the area the next day (Daily Mail, 16 December 1919). (Earlier still is a 1917 article by him that appeared in Wide World Magazine.) Needless to say, these claims directly contradicted Jordan's accounts in his two books, in which no mention was made of the dingonek charging him, and in which he and his helpers returned not long afterwards rather than the next day. Such notable discrepancies cannot help but make me wonder just how reliable the remainder of his dingonek testimony was...

Dramatic dingonek representation that includes a brow-borne horn and sting-tipped tail, features not normally ascribed to this cryptid (© Randy Merrill)

Dramatic dingonek representation that includes a brow-borne horn and sting-tipped tail, features not normally ascribed to this cryptid (© Randy Merrill)Notwithstanding this, the concept of aquatic felids is evidently not an alien one to native Africans. And the close correspondence in such creatures' descriptions over so far-reaching an expanse of Africa, cutting across many different tribal cultures and histories too, is surely indicative that there is something more substantial and fundamental to their accounts than mere folktale and superstition. Time and reason enough, therefore, for the launching of a new expedition by some enterprising seeker of mystery beasts to discover the dingonek, meet the mourou n'gou, or even journey to the jungle walrus that may – or may not – lurk in clandestine seclusion within the dark, shadow-enshrouded heart of the Ituri Forest?

Last but by no means least: an exactly comparable situation exists in South America too, from where reports of mystery cats resembling terrestrial mountain-dwelling sabre-tooths have emerged, as well as reports of water-dwelling cryptids likened to aquatic sabre-tooths, and sometimes even to walrus-toothed otters, such as Guyana's mystifying but deadly maipolina - but these must wait for a future ShukerNature article…

This ShukerNature blog article is adapted from my forthcoming 32nd book – more details to be posted here in due course...

Artistic representation of the South American maipolina (© Markus Bühler)

Artistic representation of the South American maipolina (© Markus Bühler)

Published on April 11, 2020 10:22

April 10, 2020

MONKEYS WITH WINGS IN NAPA, OH MY!!

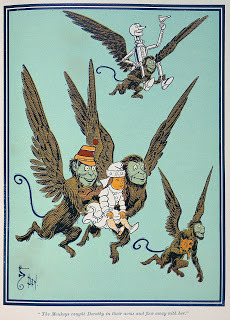

Winged monkeys seizing Dorothy and her companions, in one of W.W. Denslow's exquisite illustrations from the first edition of L. Frank Baum's classic children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) (public domain)

Winged monkeys seizing Dorothy and her companions, in one of W.W. Denslow's exquisite illustrations from the first edition of L. Frank Baum's classic children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) (public domain)Following yesterday's ShukerNature blog article regarding a lost Chinese gibbon, here's another one dealing with a simian, but not a Sinian simian, not even a similar simian – far from it! I always enjoy documenting unusual, unexpected mystery beasts – and they don't come more unusual or unexpected than this one!

Among the many memorable spectacles on view in MGM's immortal 1939 fantasy musical film 'The Wizard of Oz' (based upon L. Frank Baum's classic children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, first published in 1900) was a flock of malevolent flying monkeys that did the Wicked Witch of the West's evil bidding. According to various decidedly bizarre claims and sightings emanating from California's Napa Valley, however, these monstrous things with wings may not be entirely confined to the movies (or novels).

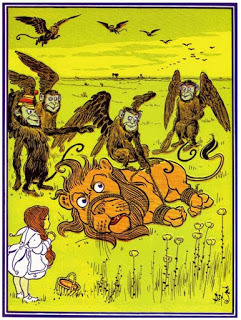

The winged monkeys snaring the Cowardly Lion for the Wicked Witch of the West in another of Denslow's illustrations from Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (public domain)

The winged monkeys snaring the Cowardly Lion for the Wicked Witch of the West in another of Denslow's illustrations from Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (public domain)In September 2018, mysterious entities with bat-like wings, red eyes, long fangs and claws, black fur, and said to bear a striking overall resemblance to said flying monkeys were reported from around Partrick Road, which is just outside the town of Napa. Apparently, they would traditionally lurk amid the shadowy trees fringing this particular stretch of secluded back-road, winding out of Napa and through a dense forest, in order to accost the young amorous couples who parked here for some private sessions of passion. Nowadays, however, presumably because fewer such sessions occur as reports of these uncanny beasts have intensified, the volant voyeurs have taken instead to pursuing any car that drives along Partrick Road, regardless of whether or not it stops. At the far end of this lonely road is the blocked entrance to a forsaken, long-abandoned cemetery once owned by the Partrick family after whom the road is named, where the flying monkeys supposedly dwell when not pursuing the neighbouring populace.

As if all of this isn't surreal enough, however, it is popularly believed among the Napa locals that the flying monkeys were artificially created by some shadowy government scientist(s) either to detract attention from more serious events of the classic X-Files variety, such as covert surveillance by mysterious black helicopters and Doomsday trials, or even as an attempt to create a futuristic type of soldier, and that they are part-monkey and part-robot. Hence they are commonly dubbed Rebobs locally. Interestingly, however, the First Nation people of Napa have supposedly been long familiar with these entities, considering them to be an ancient race of beings, and they refer to this particular area as the Valley of Fairies.

A third example of W.W. Denslow's winged monkey illustrations from Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (public domain)

A third example of W.W. Denslow's winged monkey illustrations from Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (public domain)

Published on April 10, 2020 16:10

April 9, 2020

PICTURING A LOST GIBBON? A LONG-BURIED SINIAN SIMIAN DISCLOSED

Representation of the possible appearance in life of Junxi imperialis (© Hodari Nundu)

Representation of the possible appearance in life of Junxi imperialis (© Hodari Nundu)In June 2018, a new species of extinct gibbon was officially described and named in the journal Science, and was so different from all others that it also required the creation of a new genus in order to accommodate it. But what made this find more remarkable still was that instead of merely being another fossil species, one that vanished way back in prehistoric times, this new gibbon may have only died out a few centuries ago, i.e. during historical times, and was therefore familiar to modern humanity.

Hailing from China, it was formally dubbed Junzi imperialis by a team of researchers that included Dr Sam Turvey from the Zoological Society of London's Institute of Zoology, and with whom I have been communicating regarding their highly significant discovery. It is presently known from a single partial cranium and mandible found inside the tomb of an important noblewoman named Lady Xia in central China's Shaanxi Province, dating back approximately 2,300 years, alongside the remains of several other animal species, including leopards, lynx, cranes, various domestic animals, and a black bear. It may have been a pet, because gibbons were highly prized in this capacity within China back then. Lady Xia was the mother of King Zhuangxiang of Qin and the grandmother of Qin Shi Huang, who was China's first emperor.

The research team believes that subsequent extinction of Junzi imperialis probably resulted from adverse human activities, such as hunting and habitat destruction, which, if correct, would mean that this is the very first species of ape known to have died out due to such interactions. Moreover, the team also considers it likely that this is not the only Chinese gibbon species to have become extinct in historical times – the researchers believe it possible that additional lately-lost species still await formal discovery in this huge country via the eventual unearthing of preserved physical remains.

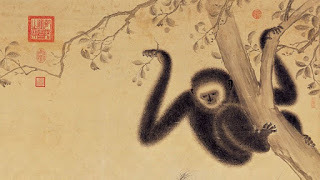

A Chinese painting of gibbons at play, dating back to c.1427 AD (public domain)

A Chinese painting of gibbons at play, dating back to c.1427 AD (public domain)There is a second, equally intriguing but entirely independent line of evidence indicating that this prospect may indeed be true. A number of early classical Chinese paintings exist depicting gibbons that do not resemble any Chinese species currently still in existence. True, these may conceivably be very stylised portrayals of still-surviving Sinian gibbons, or they may even be representations of non-native specimens brought into China from elsewhere in Asia as exotic, greatly-valued pets.

However, there is also an exciting third possibility – that such illustrations are bona fide depictions of native but now-extinct Chinese gibbon species, perhaps including the newly-unveiled J. imperialis. Moreover, this would not be unprecedented - species such as China's very own giant panda and Roxellana's snub-nosed monkey, as well as Africa's gerenuk and Grevy's zebra, for instance, were all first made known to science via early pictorial evidence before physical, tangible evidence of their reality was obtained.

I now look forward to further discoveries of this same nature being subsequently made in China, providing new, significant glimpses of the gibbons from this vast land's distant – and perhaps not so distant – past.

Detail from the c.1427 AD Chinese painting included in full above (public domain)

Detail from the c.1427 AD Chinese painting included in full above (public domain)

Published on April 09, 2020 17:44

April 8, 2020

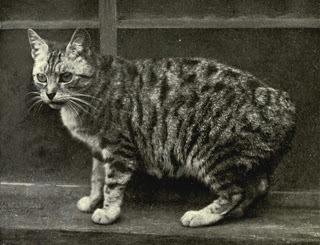

LEGENDS AND LORE OF THE MANX CAT - MYTHIC TALES OF MISSING TAILS

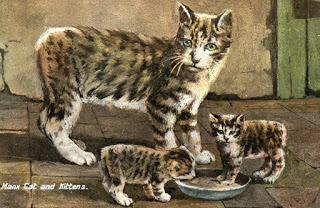

Vintage picture postcard depicting a female Manx cat with her kittens (public domain)

Vintage picture postcard depicting a female Manx cat with her kittens (public domain)Long ago, at the time of Noah and the Great Flood, the Manx cat sported a magnificent bushy tail, of which he was inordinately proud - so much so that, once aboard the ark, he took great delight in flaunting it in front of all of the other animals, especially the dogs, which he teased unmercifully. Inevitably, Noah spent quite a hectic time restraining them from inflicting grievous bodily harm upon their feline tormentor during the ark's 40 days afloat. When at last the ark came to rest on Mount Ararat, however, it did so with such a lurch that Noah was momentarily distracted, which provided one of the dogs with the perfect opportunity to take its revenge - by lunging forward and biting off the Manx cat's flamboyant tail with savage glee. And from that day forth, the Manx cat has been tailless.

TALES OF TAILLESSNESSThe above is just one of many memorable legends and myths that have sprung up over the years concerning the Isle of Man's famous feline inhabitant, and why it has no tail.

Incidentally, for my overseas readers, the Isle of Man is a smallish island situated in the Irish Sea between northern England and Ireland, and although part of the British Isles it is not a part of the United Kingdom; it has its own parliament, language, coinage, and postage stamps - plus its tailless cats.

Another Noah-inspired example of Manx cat myth tells of how, at the onset of the Flood, Noah was anxiously calling out to all of the animals to come aboard the ark as quickly as possible. Within a short time, most of the diverse multitude of species, breeds, and varieties were safely aboard, but with typical feline independence the Manx cat dawdled languidly until the very last moment. Only then did he leap onto the ark - but he did not leap quickly enough. For as soon as the cat landed aboard, Noah slammed the ark's heavy door shut - and inadvertently trapped the desultory cat's tail in it, which snapped off like a brittle twig and was soon washed away by the Flood.

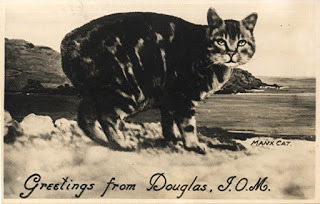

Manx cat on an old Isle of Man picture postcard for tourists - Douglas is the Isle of Man's capital (public domain)

Manx cat on an old Isle of Man picture postcard for tourists - Douglas is the Isle of Man's capital (public domain)A very different but equally imaginative legend tells of how, in early days long past, Irish soldiers on the Isle of Man would slaughter great numbers of newborn cats here in order to cut off their tails, which they used as magical talismans for decorating their helmets and shields. As a result, the mother cats became so distraught by this wanton massacre of their offspring that as soon as they had given birth, they would immediately bite off their kittens' tails themselves, thus preventing them from being killed by the soldiers. Consequently, after many generations of such activity, this island's cats began to be born tailless.

This curious account owes rather more to Lamarck than logic - because it reiterates a long-discredited theory of heredity formulated in 1809 by French naturalist Jean Baptiste de Lamarck, and known as the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Lamarck postulated that physical characteristics acquired by an individual via external (i.e. non-genetic) means (such as taillessness caused by physical severing of the tail) could be transmitted to that individual's offspring. Needless to say, Darwin's evolutionary studies and Mendel's genetic researches ultimately exposed this theory as being wholly fallacious.

Isle of Man one crown coin depicting a Manx cat, issued in 1970 (© Raimond Spekking/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)

Isle of Man one crown coin depicting a Manx cat, issued in 1970 (© Raimond Spekking/Wikipedia -

CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

)Among the more recent fables and folk legends regarding the Manx cat are ones that variously attribute its tail's absence to inattentive butchers, the sharp wheels of horse trams, and even exceedingly close encounters on the racing track with over-enthusiastic TT bikers!