Sara Ryan's Blog, page 13

January 23, 2013

Interview with Gordon Dahlquist, author of The Different Girl

I was lucky to get an advance copy of Gordon Dahlquist’s new novel, The Different Girl, which pulled me in immediately, starting with this quote from the first page:

I’m not sure how old I am, mainly because there are so many different ways to tell time — one way with clocks and watches and sunsets, or other ways with how many times a person laughs, or what they forget, or how they change their minds about what they care about, or why, or whom. And there are times when something happens that you don’t understand — but somehow you still know that it’s important — like walking through a door you only notice when you hear it lock behind.

And he was kind enough to answer some questions about the book.

SR: I’m intrigued that The Different Girl started life as a libretto. How does your experience as a librettist and playwright influence you when you work on a novel?

GD: One factor is that in a play the wider world is conjured up through what people say – which, since the most interesting dialogue leaves many important things unsaid, creates a lot of interesting room for an audience to fill in the gaps. While there’s obviously a lot of conversation in The Different Girl, a bigger theatrical echo is the way much of Veronika’s narrative similarly hinges on what she doesn’t say. Another related point is that in the theatre one writes for a very specific physical situation. Though much of The Different Girl is about making sense of experience – which can seem abstract – to me that impulse is always rooted in Veronika’s reaction to concrete places and actions.

SR: I love how much attention Veronika pays throughout the book to what it means for things and people to be different, and how frequently the word itself appears. At what point did you know that The Different Girl would be the title?

GD: From the very beginning. I almost always have a title in mind before I start to work on a book or play, even before I quite know what the title means – it’s something I’m a little superstitious about. But I don’t tend to work with outlines, or to plot too far ahead, so much of my method is about having ideas in mind that I know I’m going to pursue, so they just naturally get developed as I go on, what I think know changes as the plot and characters expand. My plot outlines are limited to notes like: “V takes noodles to M. They talk.” Once I get a draft, of course, I’ll revise things, but I think it’s important not to know too much beforehand – I very much believe that ideas one comes up with on the way are better than decisions made beforehand (if simply because beforehand you don’t know as much). Again, some of this probably comes from playwriting. I can’t write page five of a conversation without writing pages one through four to reach it – I can have an idea of course, but not the actual words, because the actual words arise organically from what’s come right before.

SR: When Veronika says, late in the book, “I had learned to see possibility,” it made me think about seeing narrative possibility, and about how much of the way we understand ourselves and the world is based on the stories we tell about our experiences. Is that relationship, between experiencing something and interpreting it through story, something you deliberately kept in mind, or am I just projecting?

GD: Not at all – I very much share that sense of connection between narrative and understanding. It’s a frequent theme in my writing, and something I’m fascinated by, just in life – the relation of a society to its stories, how narrative strategies relate to our thinking, and to our values. Obviously a big thread running through The Different Girl is Veronika’s growing understanding of context, identifying the various factors that define her experience and how they inform one another, how story creates meaning. Because of Veronika’s nature, maybe those ideas are a little more visible – or maybe it’s that her nature allows me to create a character who’s as interested in those ideas as I am.

SR: It seems like more stories could be told in the world of The Different Girl. Would you want to return to it? And of course: what’s next for you? What are you working on now?

GD: I’ll answer these together, because they’ve become connected. I don’t have any intention, at least right now, to continue with the characters in The Different Girl – that story seems finished to me. That said, the climate in which it takes place does open up a lot of possibilities, and after kicking that prospect around for a while, I’ve started another novel set in that larger world. It’s also a science-fiction story, presently titled Second Skin, and explores the part of that world where Robbert and Irene might have come from, though from a very different perspective than either of them.

January 12, 2013

My skeletal familiar

I have a new companion in my writing room these days.

This is “Failing Sparrow,” named for the street near where artist Matt Hall found it. (He took the above photo as well; click it to go to his Tumblr.) The paper behind Failing Sparrow is a partial map of Portland; the red pin marks where Hall discovered Failing Sparrow. The apothecary jars hold some of its feathers.

Creepy? Morbid? Maybe. But I love to look at this assemblage and think about the painstaking work Hall did to reassemble and preserve it, especially when I’m trying to make a story out of thoughts that often seem as fragile and fragmentary as Failing Sparrow’s bones.

January 3, 2013

You run your railroad.

You run your railroad.

My mom has told me this, regularly, since I began the (never-finished) process of growing up. Apparently it was a phrase her dad said to her a lot, too.

What does it mean?

Nobody else should dictate your routes.

Nobody else should tell you how to get through the mountains and across the rivers.

Nobody else gets to decide whether you burn coal or electricity.

It’s liberating to run your railroad, but it’s a lot of responsibility, too. When you run your railroad, it’s up to you to fix the boiler when it bursts, or calculate the effects on the grid load when you add a new line.

I was looking back at my 2011-into-2012 post; “Easier.” I wrote then about six ways to make things easier. I’m pleased to say that the first five were already working okay when I wrote it, and they kept working throughout the year. But the last, “It’s easier not to beat yourself up,” proved to be the most challenging for me in 2012.

Because there’s something so compelling about identifying all the possible ways you’re messing up, every way you’re falling short, for maximum excoriating value. In other words, it is certainly easier, in the sense of making your life easier, not to beat yourself up — but it’s awfully damned not easy to break the pattern of constantly judging and condemning yourself.

What does this have to do with running your railroad? Well, I’ve been juxtaposing that aphorism with one of my dad’s, which he had taped up on his mirror, and which I now have taped up on mine: The trick is to keep going. If all you do is agonize about what kind of engine to build, or whether to dynamite a pass through the mountains or switchback up, you’ll never get anywhere.

Here is a case in point. I spent a lot of time early in 2012 agonizing about a thing. At the beginning of March I had a relatively large chunk of words, but I kept worrying about it and thinking I should probably trash it and start over for the eighth time rather than attempting to finish. Finally I gave up and asked for help (you can, in fact, work with consultants when you run your railroad); now, while I am not yet done, I have more than twice the amount of words I did then.

So for 2013 I plan to keep telling myself: You run your railroad. The trick is to keep going.

December 31, 2012

Two things I learned in 2012

1. Sometimes you only discover you’re overextending yourself by snapping.

2. However, this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t stretch; quite the opposite.

December 21, 2012

Five things make a post

1. If something in your car is intermittently making a shrieking sound it is a good idea to get it looked at because it may indicate for instance that you only have five percent functionality in your front brakes.

2. And so then when I was waiting for the bus because now the car is in the shop I overheard part of a family’s conversation and was pleased to be able to translate this reaction from a kid to seeing one of the little Car2Go cars:

“Parece como un zapato.” (“It looks like a shoe.”)

3. The bus was crowded but companionable, people smiling as we jostled to adjust to more new riders at each stop. I was taking it to get to Jen Violi’s winter solstice writing retreat. I’m very glad I did; it was an opportunity to pause and reflect on the year in a rapidly-formed small community. More like this.

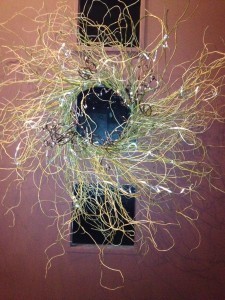

4. I saw this wreath on the way there, and liked the contrast of the scribbly-looking spiraling branches with the severe squares of the windows.

5. And because the car is still in the shop, we walked into work this morning and were ambushed:

If you cross this cat’s path there is no help for it: he will leap onto your shoulders and bump his head against your face and purr.

But we’ve seen him enraged. In fact, we’re pretty sure he’s the one with whom our cat Snag most often fought, before we decided we needed to keep him inside for his own good. To be fair, Snag may have brought these violent altercations on himself with his aggro behavior. Then again, perhaps this cat simply has a philosophy: Love up on humans. Destroy other cats.

December 17, 2012

Holidays are hard.

Years ago at Thanksgiving I invented the Rockwell Deviance Quotient, intended to measure how far off your celebrations fall from the heartwarming variety depicted in his work. I wrote about it then in a slightly jokey tone, and have referenced it a few times since.

Here’s the non-jokey thing. For lots of us, part of ‘the holidays’ is being hyperaware of absences: people who are permanently gone from our lives, or simply no longer present in the ways we remember and miss. Or maybe we’ve never had Rockwell-painting-Hallmark-card-style holidays, and the sense of absence we feel is for something that was never there in the first place.

Which is not to say that we can’t have happy holidays, and I’m certainly looking forward to mine. But there’s bitter along with the sweet.

December 6, 2012

Production and consumption

So I’m trying this thing, “Don’t Break The Chain,” which is impossible not to instantly connect to the ominous warnings accompanying the eponymous letters.

But this time I really don’t want to break it, because the concept is that every day I write, I get to mark an X on the calendar. And as the Xs accumulate, I will, apparently, be increasingly disinclined to see a day sans X, because psychology, and also habituation. Xing my fingers.

On the consumption side, I’m late to the party on Writing Excuses – the podcast, I mean, which is in its seventh season — and I’m finding it useful and enjoyable; nuts-and-bolts of story construction within various genres. I also like the end-of-episode tagline/spur: “You’re out of excuses, now go write.”

December 2, 2012

Books That Built Me: Cat In The Mirror by Mary Stolz

Every so often — the last time was in 2009 — I write about a book that was important to me as a kid and/or teen.

Not long ago I was in a used bookstore that, had it not been for the price tags and the register (barely discernible behind stacks of books), could have been mistaken for a hoarder’s, well, hoard.

It was overwhelming in the best possible way, especially when I managed to navigate the treacherous stairs to the childrens’/YA section and found Cat In The Mirror, in the paperback edition I’d checked out multiple times, but never managed to acquire, and then I’d forgotten the title.

Cat In The Mirror belongs to the New York Apartment School of 1970s YA, subcategory: Fancy. The protagonist, Erin Gandy, is growing up with significant privilege, but she’s unhappy in the brownstone where she spends more time with Flora, the family housekeeper, than she does with her parents.

It was one of the first books I read where the protagonist actively dislikes a parent. From what we see of Erin’s self-centered, image-obsessed mom, Belle, this dislike is understandable. Erin’s dad, meanwhile, is her favorite person — a thoughtful, kind, but somewhat oblivious Egyptologist manqué (I remember learning the word manqué from the book) whose actual business job necessitates a lot of travel. So the family’s moved around a lot.

Some kids adapt well to a nomadic lifestyle. Erin emphatically doesn’t. Her habit of filling her cheeks with air, like Dizzy Gillespie sans instrument, gets her the nickname of Blowfish. She vacillates between hiding from the popular kids and trying to take part in their conversations. Neither strategy is successful. The precise way the popular kids bully her — seeming briefly to include her in their charmed circle, and then viciously pulling the rug out from under her — felt absolutely true when I first read it, and still does.

But I don’t think I’d have imprinted on the book if not for what happens more than halfway through. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art (an important setting in another of my and so many other people’s favorites, The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler), Erin hits her head and wakes up, sort of, as Irun, in ancient Egypt.

‘Sort of’ because Irun seems to have been living her life before Erin showed up in her head, and yet she’s also, somehow, a version of Erin, living among people whose names and personalities echo those belonging to people in Erin’s twentieth-century New York life.

When I read the book as a kid, I didn’t get caught up in the hows and whys of the parallels. I didn’t worry about whether she’d actually gone back in time or if she was having accident-related delusions. I just utterly loved the idea that there could be someone in the impossibly distant past who was, kind of, you.

November 29, 2012

November 23, 2012

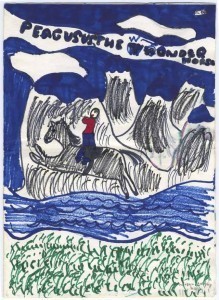

Juvenilia: Pegasus the Wonder Horse

So, I recently discovered — or rediscovered, technically — that I got an early start with comics.

Adventure comics, to be precise.

Peagusus the Wonder Horse.

(Part of his wonder, as you will see, consists in changing color from panel to panel.)

It’s a Harper Trophy Book, apparently.

PAGE 2

Panel 1: Pegasus is having his daily run.

Panel 2: Suddenly, he hears someone saying HELP! He races to the house door and waits for his master, Jenny.

Panel 3: Jenny came running out saying “Grandfather’s been KIDNAPPED!” She leaped on Pegasus.

Panel 4: They went galloping galloping into the forest.

Panel 5: Then they came to a mountain range.

Panel 6: Pegasus jumped over the mountains, one by one.

Panel 7: They finally got to a little clearing in the mountains.

Panel 8: “GRANDFATHER!”Jenny shouted. He was tied up to the mountain.

Panel 9: Jenny quickly went to him. She left Pegasus tied.

Panel 10: She couldn’t untie the knots!

Panel 11: Suddenly, Pegasus leaped free!

Panel 12: With his teeth he clawed the knots that tied Grandfather.

PAGE 3

Panel 1: “HE’S FREE!” Jenny shouted.

Panel 2: “And Pegasus freed him!” Grandfather added.

Panel 3: So they went home, riding Pegasus.

Panel 4: Pegasus got a big reward…

Panel 5: Of extra hay!

Panel 6: And the whole family was happy! (Even though it was only two people.)

Panel 7: In the morning, Pegasus had eaten his way through the hay.

Panel 8: And he was fat!

Panel 9: And that’s the end.

Panel 10: Characters: Jenny

Panel 11: Grandfather

Panel 12: Pegasus

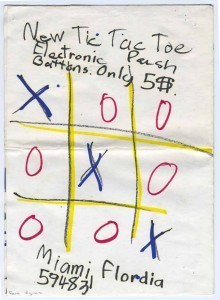

Of course, no comic would be complete without the ad on the back cover:

New Tic Tac Toe.

Electronic push buttons.

Only 5$.