Sara Ryan's Blog, page 11

July 21, 2013

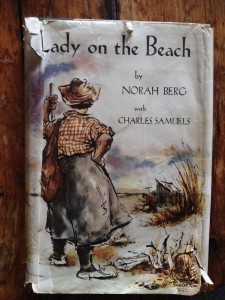

Lady on the Beach by Norah Berg

If you look at the cover of Lady on the Beach, by Norah Berg with Charles Samuels, you might think you know the kind of book it is: sentimental, inspirational, dated. That’s what I thought, too, especially when I considered the copyright date — 1952 — and read the phrase “miracle of love” on the back cover. But I was at the beach and it seemed apt to be a lady on the beach reading Lady on the Beach.

Seven pages in, you learn the reason the author and her husband moved to their tiny beach community: “A double drinking problem we’d been unable to cope with had turned us into drifters, tormented by guilt and a shame shapeless as fog and as difficult to wrestle with.” The beach doesn’t magically solve that problem. It does, however, provide razor clams, driftwood to make into furniture or burn as fuel, and neighbors:

Among our Ocean City neighbors are many middle-aged folks who have spent their lives gathering the fruit around Oregon and Washington State. They come down here each fall, when the harvests are all in, to wait for spring. On becoming too feeble to follow the fruit, they retire here to live on their old-age pensions.

A few of our neighbors at one time or another have been in prisons or mental hospitals. Others, including some of the younger men and women, came here to escape homes where they’d found no love. More, though, were misfits in the city, and are the human rejects of industry who proved unable or unwilling to adjust themselves to the harness, the checkrein, and blinders everyone must wear in a factory, a mill, or an office.

In fact this is a kind of book that I love: a clear-eyed portrait of a particular time and place, where you come to understand the people by learning how they survive their various challenges in a setting of dramatic natural beauty that can also be dangerous.

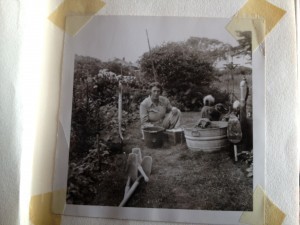

This photo was taped into the copy of the book I read. We’re pretty sure it’s the author.

July 8, 2013

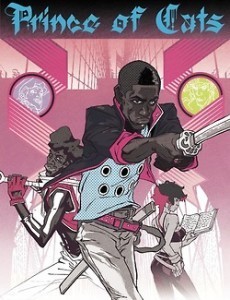

Prince of Cats by Ron Wimberly

The first time I read Ron Wimberly’s Prince of Cats, I did not pay sufficient attention to the foreword. To make sure you don’t make the same mistake, permit me to quote it in its entirety:

So I’m your DJ tonight. My name is D-pi and boys and girls, have I got a treat for you. I’ll be cutting the B-side of Romeo and Juliet from Shakespeare’s greatest hits with a hot little piece of wax called “Gratuitous Ninja.” The outcome is Ninjaupera, post-modern absurdity for the critically pretentious or the laughably subversive. Either way, enjoy.

In other words, don’t go looking for the Romeo and Juliet story you know; D-pi is taking you somewhere else. Another quote:

In Brooklyn Babel, Where we lay our scene

Here hood born Youth, adolescence Addled

Spill civil blood, make civil hands unclean;

Traded rattles for father’s swords and battled

Wimberly’s characters — some of whom are, yes, Capulets and Montagues — battle via graffiti, eloquent exchanges of insults, and swordfights. Fights can break out when one character scuffs — deliberately or not — another’s new kicks. The intrepid reporters of Duel-List magazine keep track of the fighters’ ever-shifting status, and more often than not, there’s blood on the dance floor. And the subway. And the roof.

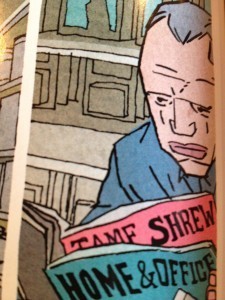

I love the palette, the language, all the cultural phenomena Wimberly gets in the mix. And some of my favorite moments aren’t the action sequences — which are impressive — but single panels. Like this one, that plays with the Shakespearean milieu:

Or this one, girls walking out of school and hiking up their uniform skirts in unison:

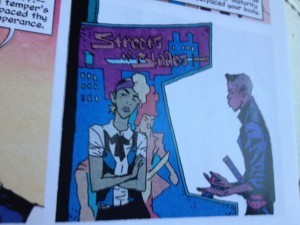

Or this one, Juliet leaning against the Streets of Blades machine while Tybalt plays, actual sword at his side:

Or this one. Petruchio commenting on his piece: “See, a man caught in words can live forever.”

Shelve Wimberly’s Prince of Cats between Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and Lethem’s Fortress of Solitude.

And if you want to know more about the book and Wimberly’s influences, David Brothers did a great interview with him at Comics Alliance.

July 2, 2013

Portland is hotter than Chicago. Weird.

I saw this building every day on my walk from where I was staying to the convention center.

I’m back from ALA, half in a post-travel stupor, half jittery with the coffee I’ve been drinking to get back to the proper time zone. Which may be the perfect state of mind in which to consume Tumblr.

Speaking of which, perhaps you’d like to see some street art or Carla’s first character sketch of Anne from BAD HOUSES?

ALA: I learned things and met people I’d been wanting to meet and saw people I wanted to see and picked up a few galleys I’m excited to read. Of course, I also didn’t manage to get other galleys I wanted, and missed some folks I wanted to see — some of whom weren’t actually there but I wished they were, some who were just elsewhere in the vastness of McCormick Place. Such is convening.

June 26, 2013

ALAness

In a few short days I’ll be in Chicago for the American Library Association conference!

On the author side of things, from 2-4 PM Sunday 6/30 I’ll be at the Diamond Book Distributors booth #2544, talking about Bad Houses. Of course, even when I’m not there, I encourage you to visit the booth & ask about the book!

And on the librarian side, at 8:30 AM Saturday 6/29 I’ll be one of the presenters at this session: Learning Labs Ignited, talking about working with teens to plan a makerspace.

And on the librarian side, at 8:30 AM Saturday 6/29 I’ll be one of the presenters at this session: Learning Labs Ignited, talking about working with teens to plan a makerspace.

During the rest of the conference you can find me, unsurprisingly, at assorted sessions about teens & maker-y stuff, or wandering the exhibit hall in a daze. (I know I’ll be in a daze, because that’s just what happens.)

If you’ll be there, see you there!

June 13, 2013

My dad explains fanzines, 20 February 1961

I’ve previously posted articles from the science fiction fanzines my dad published in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Conscientious archivist that he was, he kept copies not only of his zines but also of all his correspondence. Today I found a letter he wrote to a college friend who’d asked him about this odd hobby of making zines.

In honor of Father’s Day, here’s my dad explaining, in 1961, the history of fanzines.

Once upon a time (around 1930) there were people who were interested in science and stories about science. Some of them wrote letters to magazines which published science fiction stories. The editors printed the letters (comments on science, the stories, and the science-in-stories) and soon the readers were writing each other, discussing their common interest. Clubs were formed in some cities. Some of the people, who had begun to call themselves “fans,” began writing and publishing little magazines of their own, containing their own fiction, comments on the fiction in the professional magazines, and letters from other fans. Gradually the original interest of fans in science changed to an interest in fiction, and other topics began to be discussed in their amateur magazines (called “fanzines”). In the late thirties the Fantasy Amateur Press Association was formed to distribute publications of members to the whole membership at once, every three months. The interests of fans, as fans, broadened to include almost any topic; more and more people became interested, through reading the pro magazines, which published news of fandom’s activities — which came to include conventions, conferences, and other amateur press groups besides the F.A.P.A. — commonly, fapa. Nowadays many fans read very little science fiction, but are held together by other interests — mainly, I think, the need to communicate. This is done by letter, by gathering in convention (this year it’s Seattle), by publishing fanzines, both for general distribution and for distribution through the amateur press associations, or apa’s. (Apa’s, by the way, antedate fans, I believe; originally they were groups of printers who just got a kick out of printing.)

Bw (my dad’s zine, Bandwagon — sr) is a fapazine, and I think you could figure out from the above that that’s a fanzine which is distributed through fapa. There are 65 members; requirements are dues of $3 per year plus publication of 8 pages of material. When a member publishes, he sends to a designated officer enough copies of his zine for the whole membership. This officer (the “official editor”) assembles one copy of each publication received in the previous three months into a “bundle.” This is done for each of the 65 members. On specific dates in February, May, August, and November, the bundles are mailed out to the members. Almost anything, as I said, might be discussed, but much of the material is “mailing comments” — comments on remarks made in the previous mailing. Which is why so much of a zine is incomprehensible unless you know what’s gone before. Recently there have been hot discussions on sports cars, jazz, and capital punishment, to name a few.

So there you have it.

June 8, 2013

Karen Joy Fowler at Powells

I’m a huge admirer of Karen Joy Fowler‘s writing. I’m also lucky enough to have been a student of hers at Clarion. So when I saw that Portland would be one of the stops on her tour for her amazing new book We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, I couldn’t imagine a better way to spend a Friday evening.

Really, as Barbara Kingsolver says in the review linked above, it’s better to know as little as possible about the book before you read it. So instead of telling you about the book, I’ll tell you a few things she said during the Q&A.

I asked about research. “One of the great things about research is that you can persuade yourself that almost anything you want to do is research.” Here is an example of research:

Someone else complimented her on her nuanced and well-developed characters, and asked if she models them on real people. She explained that she had done this once and it went very badly, because all the sterling qualities she had included in the portrayal were outweighed by a single reference to the tendency of that person’s hair toward greasiness. Now, she said, “What I generally do when I’m starting a character is to start with a story someone else has told me about someone I do not know.”

Someone asked her thoughts on adaptations: book-to-movie, book-to-audiobook, etc. “I feel the author should be let to run rampant through whatever is next.”

We learned that she wrote her first book at age five, a collection of short stories with identical plots: a baby animal is separated from its parents, there is a tense middle, and then a happy ending where they are reunited.

I said I wouldn’t tell you about the book but I have to quote this paragraph:

Our parents, on the other hand, had shut their mouths and the rest of my childhood took place in that odd silence. They never reminisced about the time they had to drive halfway back to Indianapolis because I’d left Dexter Poindexter, my terry-cloth penguin (threadbare, ravaged by love — as who amongst us is not) in a gas station restroom, although they often talk about the time our friend Marjorie Weaver left her mother-in-law in the exact same place. Better story, I grant you.

As who amongst us is not.

I’m a little sleepy today, because when I got home from the event I read We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves straight through. Go thou and do likewise.

May 30, 2013

BE URSLF

This wisdom courtesy of one of Portland’s many yarnbombers.

It made me think of this good long essay that I’ve been musing on by the poet David Biespiel: Follow Your Strengths, Manage Your Weaknesses, And Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys.

I’ll tell you in the typically elliptical fashion I employ here that I’ve been working on a Thing that differs in significant ways from Previous Things I’ve written.

And because the thing is different, I’ve been feeling like I should be different, too; a different kind of writer, with a different approach to writing.

That essay made me realize that while making this Thing work will require me to learn some new skills, it doesn’t mean I should disregard the skills I already have. And if I’m more deliberate about recognizing those skills and how they can move the story forward, it’ll help with the whole making-it-work endeavor.

Does this seem like an incredibly obvious realization? Then I challenge you to do the same with a project that you’re working on. Stop beating yourself up about not being able to X the way Y does, and let yourself enjoy your ability to Z.

May 24, 2013

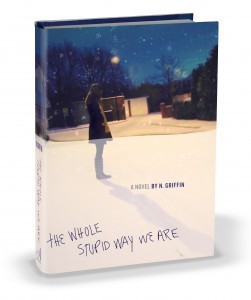

Interview with N. Griffin

Hello!

In case you were wondering, this is not going to morph into a blog composed exclusively of me interviewing other authors. But I sure like doing said interviews, and I am now pleased to present another one!

I was intrigued by N. Griffin’s debut novel, The Whole Stupid Way We Are, from the moment I heard its excellent title. It’s about Dinah, church choir director’s daughter who sings off-key, and Skint, who walks coatless through brutal cold; about their friendship and the things that divide them. For a book whose characters have some very hard-to-deal-with experiences, it’s surprisingly funny, and the prose is always precise, whether evoking an escape from detention, the play of sunlight on a toddler’s feet, or how it feels when your help can’t fix what you want to fix.

So I asked N. Griffin some questions. I’ve tried to avoid spoilers, but if you are extremely concerned about such things you might want to wait to look at this interview until you’ve finished reading the book. Which, in case it wasn’t obvious from the above, I recommend that you do.

SR: I love the names in TWSWWA. How do you choose character names?

NG: Thank you! Naming the characters is one of the most fun parts about writing books, I think. For TWSWWA, Dinah’s name came first. When I was just starting to write the book, I was working with a woman whose name I adored. Let’s call her Mynah Deech. I loved saying “Mynah Deech” so much I worked it into conversation at every opportunity—“What do you think Mynah Deech would think of this?” and “We better check with Mynah Deech!” In fact, I wanted to steal her whole name for my book but I thought that would be too weird so I settled for a name that rhymed with it and came up with Dinah Beach. All of the other names just felt right to me, and some of the names are sort of a broken-up, messed-up version of a word that was central to my heart while I was writing the book. A MYSTERY! :)

SR: I was struck by Skint’s angry passion about social issues far removed from the considerable challenges of his day-to-day life. At what point in the writing process did that aspect of his character become clear to you?

NG: It was always clear to me; one of the first things I knew about Skint was this. I think this aspect of his character came from two places for me—first, I know so many kids who care this much about suffering and the world, and we never seem to pay attention to that aspect of teenagers. We prefer to think they are only and entirely self-centered, and I know that is beyond not true. I also knew that Skint’s passion for this was an outlet for all the anger in his life—he can’t express what is going on at home, but he can get riled up about the world in a public way, and all his personal hurt and upset gets added to his natural compassion and comes out with all the intensity that would suggest.

SR: Dinah genuinely cares about Skint, but also seems to see him as a project or a job. She comes up with strategies to distract & cheer him: “Outings, she thought firmly, and good ideas to think about. Pretending, talismans, things to do with trees.” I think many of us have known and/or been Dinahs. What do you think drives that particular intense need to help people who may or may not benefit from our efforts?

NG: For Dinah, I think it’s the same intense love and compassion as Skint has, only hers is focused on the personal and her own aching for Skint. I also think she truly thinks she’s helping him, and that can be an intoxicating feeling—who doesn’t want to feel like they are needed like that? But the balance is off for sure, and I think that’s something lots of people take years to make sense of. Not that I know anything about that. No sirree. ;)

SR: I hope I can say this without giving too much away: I was impressed that you leave certain things unresolved at the end. Did you always know you wanted to give that shape to the story, or did you have previous drafts that went in other directions?

NG: Nope, that was always how it was. I think I wrote the last scene when I was only a third of the way through the first of my million drafts. For me, the arc of the story is that of their friendship, not of their whole entire lives. And when that arc was complete, so was the book.

SR: And finally: Dinah and Skint regularly embark on “Fantastic or Excruciating?” adventures:

“An FoE is an entertainment where you can’t tell beforehand whether it will be fabulous and surreal or only just a misery-making fiasco that will make you ache for the performers involved because it is all so awful and the performers are unaware. Or maybe they are aware. And then it is even worse.”

Have you ever done this yourself, and if so, can you describe one?

NG: Oh, my lordie, yes, all the time and even still! Every single FoE in the book except for Walter is one that I have actually experienced. There are so many more, too! I would adore to hear about other people’s FoE’s. I live for this kind of thing.

SR: Thanks for answering, NG!

May 8, 2013

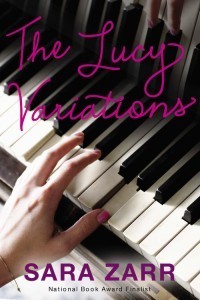

Interview with Sara Zarr

The Lucy Variations is about Lucy Beck-Moreau. As the book opens, Lucy is a sixteen-year-old former world-class pianist, and current…well, that’s the question. When your identity has been entirely constructed around one thing for as long as you can remember, and you walk away from that thing, how do you figure out what else there is, who else you can be? I loved this book, and I was excited to ask Sara Z. some questions about it. Minor spoilers below.

SR: Early on Lucy’s mom says that Temnikova’s death is ‘terrible timing’ — a cringe-worthy comment, but somewhat more understandable when you know that she was preparing Gus for an important performance. What was it like to write Lucy’s mom and Grandpa Beck, characters so focused on achievement that they often don’t seem to see other ways to experience life as even possible, let alone desirable? Was it easy, like letting a competitive part of yourself off the leash, or more of a stretch?

SZ: I was surprised how much I enjoyed writing Mom and Grandpa Beck – maybe you’ve tapped into something here about why I liked it. Maybe they represent my superego! As far as “easy” vs. “a stretch”, I think writing characters like that is always easy in the first draft, when they’re being the cardboard-cutout versions of themselves so that you can move conflict forward. In revision, for them to really work, they need to be humanized in some way. They need dimension, and opportunities to show cracks in the armor. That’s a writing challenge–you don’t want to pull your punches and make every antagonist into “a crank with a heart of gold,” because some people are just truly difficult or calcified. But, it’s very rewarding work. I love to see a previously-2D baddie or antagonist have a moment where they show another side or potential side, without quite joining the ranks of the “good guys.” One of my favorite and unexpected things about the final version of the book is the understanding Lucy comes to about her grandfather.

SR: I played violin growing up, and while I was never remotely close to the Lucy level, I definitely remember the stress of preparing for recitals, solo-ensemble festivals, & concerts. Do you play any instruments? How did you research the musical details in the book?

I grew up around music and especially classical music. My parents met in music school at Indiana University and were both quite good. My father, especially, had made it his career for a time earlier in their marriage. He conducted and sang, and held several professorships at music schools post-college. My mother plays guitar, piano, and cello, and is also a singer, songwriter, and arranger. By the time my sister were old enough to know what was going on, neither of my parents were making their livings in music but it was always a big part of our lives. I played the clarinet, and I was nowhere near Lucy’s level, either. My sister played violin and got to the point of playing in some competitions, and she could have probably gone further if that was her passion. As far as research, I did ask my mom some stuff, and I also attended a big piano competition that’s held here in Salt Lake (a fictional version of it appears in the book). I went to watch a master class, where a young musician performs a piece and then a seasoned and often well-known (in that world) musician critiques it and leads the musician through workshopping the piece. In front of an audience! I can’t imagine. The pressure seems incredible. A lot of Lucy’s personal interaction with the music just comes straight from my own love of those pieces.

SR: When did you decide to include the musical notations as section headings? I love them.

Thank you! This is one of those funny stories. I was talking to a colleague, E. Lockhart, on the phone about the book while I was still drafting it. And I don’t remember exactly, but I was kind of feeling uncertain and unfocused about how to present or organize it. And she said something like, “Well, it’s called The Lucy Variations so I assume you have it structured like a musical piece…” “Um, no. But that’s a good idea!” It was one of those things that seems so obvious now but hadn’t crossed my mind. Once I started thinking about it that way, it helped with the structure of the story. I’m always in favor of things that help with structure, because writing a novel is a fairly overwhelming task, as you well know!

SR: Early on, Lucy thinks: “She had to be careful with guilt. Once she went off that edge, the downward slide might never stop.” Perhaps it’s TMI to say it, but this passage really resonates with me. Why do you think guilt can be so seductive?

SZ: I wish I understood it better myself, as it’s one of my own personal trapdoors. I guess like a lot of things, guilt provides a kind of narrative for the events of your life story. It’s something to identify with, and in a way if you’re preoccupied with guilt maybe you feel like you have some control over the situation. “This thing happened and it’s my fault” (directly or indirectly, falsely or rightly) implies a kind of power, and maybe if it’s “about you” that way, it means there’s some hope for effecting a solution. Of course usually the things we feel guilty about aren’t in fact about us, and the solution isn’t up to us (at least not totally), and helplessness or powerlessness can be harder to face. Maybe! I don’t know.

SR: I love that Lucy decides to impress Mr. Charles by writing a paper about an author she knows he loves. I once tried very hard to love Crash by J.G. Ballard because of a particular instructor’s fondness for the book. What’s something you’ve done to impress a mentor?

SZ: In the first intensive writing workshop I ever took, I got a big crush on the teacher. He cited Ford Madox Ford’s THE GOOD SOLDIER as one of his favorite novels. So of course when I got home I read it, hated it and didn’t understand it, and emailed him to say how much I’d enjoyed it. I hope he doesn’t read this. (Hi Robert!)

SR: On a related note, another thing I think is great in Lucy Variations is that you show not just how appealing and thrilling it can be to have a mentor, but also the attractions and dangers inherent in being one. What makes mentoring relationships compelling to you to explore?

SZ: Oh, there are so many reasons! For one thing, it’s incredibly flattering when someone wants to do what you do and sees you as someone who has “arrived” in some way, especially in a professions in which there are so few tangible (or tangibly believable) evidences that you have something to offer, that your work matters in a lasting sense. Giving advice and encouragement is so much easier and enjoyable than needing advice and encouragement. Feeling established enough to warrant mentees is much better for the ego than feeling like a nobody. Being admired feels great. Those are the ego-based reasons, I guess. In a purer way, it’s so exciting to see talent in someone–especially someone young, or younger than you–and be in a position to help nurture it and encourage it. When you can successfully do that, you really feel like you’re doing something good for another person, directly, and it’s a moving thing. Then when it’s time to let go, and see your birdie fly the nest, that stirs up a whole lot of your own issues. As far as Will’s relationship with Lucy, I think there’s that pure side to his intentions, but he’s also human and nearing middle age. At one point in the writing process and in the midst of my own midlife crisis feelings, I went to see a friend’s daughter in her school play. And the youth and exuberance and beauty of the high schoolers on stage just killed me that night for some reason, completely leveled me. That fed directly into the scene where Will tries to explain to Lucy how painful it is sometimes to be so close to that kind of youth and beauty and talent, with his own sense of the newness of life and the act of creation behind him. Mentoring someone young lets you experience that again, and for a minute you can forget that it’s their life, not yours.

SR: Thanks so much, SZ!

May 3, 2013

Short and scattershot

At my coffeeshop of choice, I’m always compelled to rearrange the figurines.

Last five books I’ve read:

Why Don’t You…? Diana Vreeland: the Bazaar Years

You should listen to this Stumptown panel about freelancing with Katie Lane, Erika Moen, Natalie Nourigat and Matt Bors.

You should also read this post by Wendy Stephens, Splitting personalities: how some teens are choosing privacy on the YALSA blog.

Last but not least, citizens of the Tumblrverse, are you following the Bad Houses tumblr? I would enjoy your company there.