Michael Pryor's Blog, page 27

October 10, 2011

Writing and Magic

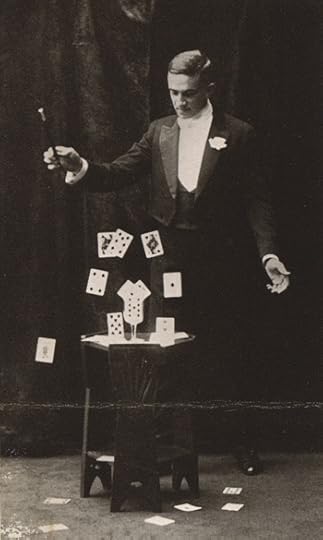

As a fantasy writer, I spend much of my writing time about magic, how it works and its effects on the people and societies in my stories. In 'The Laws of Magic' series, for instance, magic is a codified, rational endeavour which is explored and experimented with in the same way that happens with science. The integration of magic with technology and other aspects of life provides a fascinating backdrop for the narrative.

After writing about magic so much, a few years ago I decided that it was time to stop being so theoretical. It was time to actually learn some magic.

I enrolled in a Council of Adult Education short course in Close Up Magic. Six Saturday mornings, three hour sessions run by the astonishing Simon Coronel. This young man is amazingly talented, a seasoned professional in demand here and overseas. In the first session he opened by just running through a few basic moves in front of us. And I mean, literally in front of us. He wouldn't have been more than a metre away while the twenty course participants (we all fancied ourselves as cluey individuals, of course) watched as hard as we could, looking for the methods he used.

I couldn't see a thing. Right in front of my eyes, he made coins disappear, cards turn into other cards, bits of rope pass right through his arms, the works. No doubt about it, this guy was magic.

Gradually, with great good humour and endless patience, Simon taught us all how to palm coins and force cards, at a beginner level of course. That didn't stop us from feeling mighty proud of ourselves when we went home and wowed the family. Or not.

So now I can do a few bits and pieces when I do school visits, in between talking about my books. And after a while, practising with my Bicycle brand cards, it occurred to me that writing is actually a lot like magic or sleight of hand (or 'close up illusions' as Simon prefers).

It goes like this. Sleight of hand basically comes down to a combination of applied psychology and diversion. The applied psychology is working on held beliefs, getting people to assume what you want them to assume. It's also about the persistence of memory – and the faultiness of memory, and using this to its fullest.

The diversion part is interesting. It's the old 'look over here while I arrange this rabbit under the table ready to be pulled out of the hat'. There are many methods to divert (and distract) the audience's attention, and they're all useful to a performer.

So how is this like writing? Well, the applied psychology is pretty straightforward. Writers are always playing with a reader's assumptions and expectations, confounding them or fulfilling them – or stretching them out via the favourite tool of suspense. We seed red herrings, we foreshadow, we create sympathy for a character by revealing characteristics common to readers' experiences and then we heartlessly use this to propel readers forward.

But diversion? That's perhaps more subtle, and it goes pretty much like a magician getting you to look at that sleeve that he's got nothing up, while he pulls something out of his pocket with the other hand. Writers get readers to concentrate on some breakneck narrative while we sift in some other stuff – background detail, character motivation, relationship indicators, weaknesses and fears, subtle details like that. We don't want the reader to dwell on them, so we get them to look at the car chase, or the fist fight, or the heated argument between the woman and her no good cheating husband who is on his last chance and she means it this time. The reader is diverted, and doesn't notice that their pocket is being picked while they're at it. Or, rather, that something is being left in their pocket, something that will become very valuable later on.

It's magic. Writing is like magic.

October 4, 2011

Great Australian Literary Mashups No. 1

September 25, 2011

September 24, 2011

Extinction Gambit Teaser No. 4

'In the middle of all the mayhem, Kingsley found a split-second to admire her swordplay, her aim and the quality of her taunting – her descriptions of her attackers' physical failings and her estimations of their family origins made them even more determined to drag her from her perch. She'd thrown back her hood and her hair flashed silver as she swivelled, keeping her attackers at bay with such elan that it was worthy of applause.'

September 22, 2011

The Realm of the Ridiculous

It's time again for me to show my approbation for the clever, insightful and b0undlessly inventive folk over at The Realm of the Ridiculous. I applaud their efforts

September 19, 2011

Holmes Sweet Holmes

I'm going to make a big claim here: Sherlock Holmes is the forerunner of Harry Potter. And of Katniss Everdeen. And of Percy Jackson, Edward Cullen and Alanna of Trebond.

Like the other characters I've listed, Sherlock Holmes has leaped from the pages and become more than a fictional character. Today, we are accustomed to fans and the avidity with which they read. They love their books and the characters in them, and they aren't content to leave them within the covers of the novels. They speculate about them, their lives, their relationships, their hopes and dreams. They extrapolate, imagining their journeys after the books end. They create pasts, fill in gaps, worry at details. They write fan fiction.

Just as the readers of the Holmes stories did a hundred years ago.

Sherlock Holmes is the ancestor of all this. Arthur Conan Doyle had an audience that was as fervent as the most rabid of today's fans. When he became tired of writing Holmes' stories and killed him off in 'The Adventure of the Final Problem' (1893) the uproar was deafening. Eventually public pressure resulted in his resurrecting the detective in the sort of way that would be familiar to any viewer of long running soap operas. I suggest that this was the point at which Holmes stopped belonging to his creator and instead became public property.

The appeal of the epicene detective continued to grow after ACD's death. Movies and radio featured the adventures of the Baker Street denizen, and groups of what we would today call 'fans' began to spring up. The Baker Street Irregulars was founded in the USA in 1934 to study and celebrate the tales. The Sherlock Holmes Society of London began in 1951 for the same purpose. Both perpetuate the spirit of the Holmes' stories and aim to keep the spirit alive through discussion, analysis and speculation – just as many Twilight or Harry Potter fans do today. Of course, the Holmes fan groups didn't have the internet to assist their discourse, but managed to overcome this through ingenuity, perseverance and liberal use of the mimeo machine.

Holmes and Holmesiana continues, of course. Time has not wearied the tales and the Holmes fandom is stronger than ever, even though some of the more traditional adherents might shudder at being called 'fans'. The Robert Downey junior movie and the Benedict Cumberbatch TV series hasn't so much breathed new life into the legend as carried the torch forward. We may be living in a Sherlock Holmes renaissance.

I love this enthusiastic adoption of a character by his readers, and I see it as part of the magic of fiction. When it works, the reader and the writer effectively collaborate to create something wonderful, something that can have a life of its own and step off the page. It becomes a shared creation, something that is cherished, nurtured and cared for.

Sherlock Holmes achieved this status a long time ago. He set the benchmark for user adoption.

September 18, 2011

A Thousand Words

A couple of days devoted to books, reading and writing and talking about books, reading and writing can't be a bad thing, can it? The 'A Thousand Words Festival' (yes, that's actually correct) is on this Friday and Saturday (23 and 24 September) at the Northcote Town Hall. Lots of great writers will be appearing – Leanne Hall, Cath Crowley, Tim Pegler, Holly Harper, Andrew McDonald, Steph Bowe, Fiona Wood, Simmone Howell, Marisa Pintado, Sally Rippin, Sue deGennaro, Aimee Said and bloggers Megan Burke and Bec Kavanagah. A great line-up and it promises to be a fun time. See you there!

A couple of days devoted to books, reading and writing and talking about books, reading and writing can't be a bad thing, can it? The 'A Thousand Words Festival' (yes, that's actually correct) is on this Friday and Saturday (23 and 24 September) at the Northcote Town Hall. Lots of great writers will be appearing – Leanne Hall, Cath Crowley, Tim Pegler, Holly Harper, Andrew McDonald, Steph Bowe, Fiona Wood, Simmone Howell, Marisa Pintado, Sally Rippin, Sue deGennaro, Aimee Said and bloggers Megan Burke and Bec Kavanagah. A great line-up and it promises to be a fun time. See you there!

September 14, 2011

Occupational Hazards of Writers

It's poorly appreciated, but writing is an occupation which has hazards. Most writers, at one time or another, will suffer from at least one of the following diseases, conditions or injuries. Most are treatable and with appropriate therapy writers can look forward to living relatively full and normal lives.

Adjectivitis: condition especially pronounced at first draft, where adjectives spawn, multiply and run rampant through one's writing.

Criticosis: a type of writing paralysis caused by overly active and insistent self-criticism.

Swelled Head Syndrome: condition that comes from reading too many glowing reviews. Rare.

Commadosis: An proliferation of commas so virile that they infect and convert all other punctuation.

Over Capitalisation: particularly common in Fantasy writing, where everything is made strangely Portentous by Splashing Capital Letters around Willy-Nilly.

Adverbia: the helpless need to add adverbs to every verb, relentlessly, inexorably, unstoppably.

The Grumps: envy stemming from the success of other writers. Common.

My Own Myopia: a form of selective blindness where a writer cannot see his or her own poor writing.

Forehead Haematoma: bruising to the brow, resulting from banging one's head on the desk because of recalcitrant scenes, characters, plot developments etc.

Weighty Word Syndrome: a condition where every single word seems to weigh hundreds of kilos and requires commensurate effort to put in place. See 'Immense Sentence Disorder'.

Hyperplotting: a deep-seated compulsion to construct narratives that rely on the regular use of the word 'suddenly'.

Complications Complex: a form of writer delusion where 'Complicatedness' is mistaken for 'Complexity'.

Startled Narrative Disorder: a propensity to organise a story via liberal use of the word 'suddenly'.

Hyper-elastic Temporal Insensibility: An acquired condition where the time between 'now' and 'that deadline' subjectively stretches so that weeks feel like years, decades or periods of time usually devoted to delineating geologic eras.

Deadline Whiplash: An acute neck injury caused when a writer realises that that far-off deadline is actually, really, unmovably next Tuesday.

Naturally, this list is not exhaustive. Writers are more than capable of inventing new conditions at the drop of a hat. It is only through regular donations to writing-related medical research that we can hope to ameliorate the effects of Writing Diseases.

Give so that they may write.

September 11, 2011

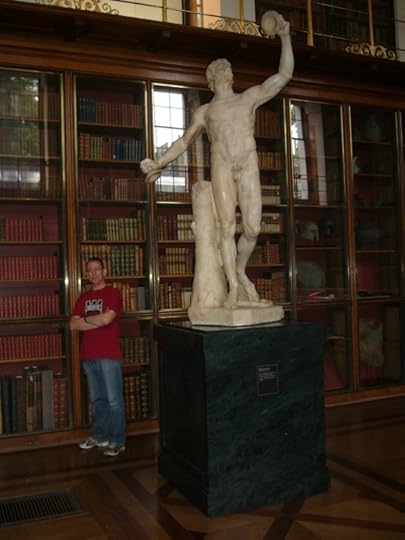

Relaxing in my library

I lie, of course. It's the Enlightenment Room at the British Museum. But if I had a library in my home, it'd be something like this. With ladders to reach the books on the second floor. Of course.

Extinction Gambit Teaser No. 3

'To an exponent of anti-incarceration, a trap was not a trap: it was a challenge.'