Michael Pryor's Blog, page 26

November 20, 2011

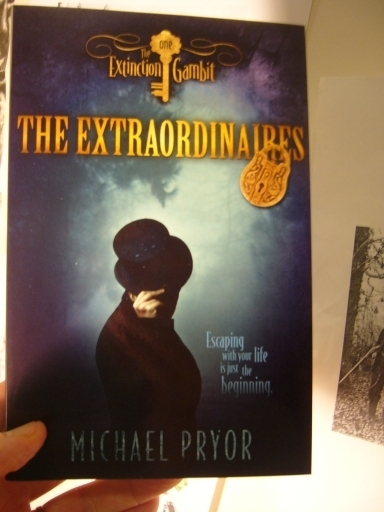

Book Launch!

Everyone is invited to the launch of 'The Extraordinaires 1: The Exinction Gambit' on Wednesday 7 December at the Northcote Library (Separation St, Northcote Vic 3070). For more details, visit the Darebin Libraries site

November 16, 2011

Writers Write: My Favourite Book 3

Richard Harland

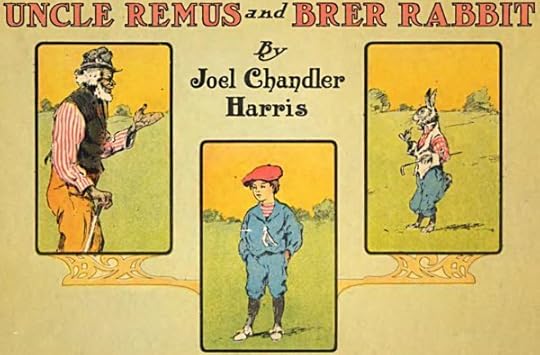

Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit

Today's Guest Post has Richard Harland reminiscing about his cherished book from childhood. Richard is one of Australia's most popular YA Fantasy writers.

The first books I truly loved when I was old enough to read for myself were two books of Brer Rabbit stories. I know Joel Chandler Harris collected and wrote out the original stories, and I've tried to read them as an adult, but the dialect was too heavy and I wasn't interested in the Uncle Remus framing narrative. These books were the stories re-told in more modern English—I wouldn't have a clue who did the re-telling or who drew the illustrations. Still, it wasn't fully modern English, because the flavour of the original was still there in phrases like 'licketty-split' and 'Brer Fox sez, sez he'. I remember the animal characters were always 'sauntering along' and being ''cute' (i.e. acute, smart).

Smartest of all was Brer Rabbit. I just loved the way that rabbit could always come up with a way to escape from any scary situation. And there were many scary situations, where Brer Fox and Brer Wolf were on the verge of gobbling him up. (Wolves were always the baddies in my personal bestiary—I had a whole lot of nightmares about them.)

I tell a lie—Brer Rabbit wasn't the smartest of all, because one animal could always outsmart him: Brer Tortoise! I wasn't so fond of the tales where Brer Tortoise turned out to be even cleverer than Brer Rabbit. The rabbit was my hero, and I always wanted him to win.

I can almost smell those books as I type this; and I can see the illustrations, shaded black and white drawings plus one colour. Some pages had green colour in the illustrations, some blue, but I remember the orange ones best.

I wonder how many times I read those stories? As an adult, I've been an absolute non-re-reader. I could count on the fingers of two hands the books I've read a second time. (Not counting re-readings because I had to give a lecture on the book.) Well, maybe three hands. But I bet I read those Brer Rabbit tales not less than a hundred times each.

I had no idea where those tales came from when I was a kid. They belonged to a special universe of 'sauntering' and being ''cute'. I knew there were no melon patches where I grew up (in England) but I don't think I consciously realised that the setting was American. I certainly never knew they were oral stories told among slaves, with sources going all the way back to Africa.

Richard's latest book is 'Liberator', the sequel to 'Worldshaker'. 'Liberator' came out this year from Allen & Unwin in Australia (also UK, France and Germany the US to follow in 2012). For more, visit Richard's website. He also has a blog and a wonderfully generous site dedicated to writing tips.

November 14, 2011

Extraordinary People: Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard

Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard

One of the best (and most unexpected things) about being a writer in this interconnected world is that I'm in touch with people who are interested in books, reading and writing, and they live all over the place. When it becomes known that I have various research needs, these clever individuals come to the rescue, often pointing me toward the remarkable, the extraordinary and the outlandish – just the sort of thing I revel in.

I've mentioned fellow bibliophile Stephen Bresnehan before, and he was the one who brought the imperiously named Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard to my attention. After some investigation, I've come to the conclusion that HHP was one of those people that would be difficult to make up. On the other hand, his life was so rich, so varied, so remarkable that it's a lesson for a writer in how much goes into the making of a person.

HHP was one of those Edwardian fellows who could have stepped out of the pages of Kipling. To know that he wrote Sniping in France as a guide to those chaps in the trenches who were going about it in entirely the long way is an insight into the man. The book is a sometimes startling look at other days and other ways, with an admiring foreward by General Lord Horne of Stirkoke, who begins with: 'It may fairly be claimed that when hostilities ceased on November nth, 1918, we had outplayed Germany at all points of the game.'

Hesketh Vernon Hesketh-Prichard was born in 1876 in India at the height of the British Raj. His father was an officer in the King's Own Scottish Borderers and had the poor timing to die a month or so before young Hesketh was born. His mother, Kate, brought him back to England and a life ensued.

He went to Rugby School, college in Scotland and then went on to study law, which he never practised. Life became too busy.

HHP was an outstanding cricketer, a tearaway fast bowler who eventually played for the MCC and was a team-mate of the immortal Dr WG Grace. He had a career best of 8/32 for Hampshire against Derbyshire and was in much demand – but other things took him away from the lure of leather on willow.

He had early success as a writer and soon after specialised in travel and adventure stories. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he actually visited the places he wrote about, along the way honing his marksmanship by potting the local fauna with aplomb. He travelled to the Caribbean, spending time in Haiti and later writing some of the first detailed descriptions of secret voodoo rituals. He worked his way through Panama, documenting construction of the canal and picking up a touch of malaria, which was the sign of a true traveller. He went to Patagonia, in search of the legendary giant ground sloth. He popped up to north-east Canada, working his way through Newfoundland and Labrador before plunging into the interior.

Much of this travel was sponsored by various magazines and newspapers, the readers of which were spellbound by HHP descriptions of wild animals, rugged scenery and colourful foreigners. In between travel writing, he was spinning thrilling yarns about psychic detectives, two-fisted adventurers and cunning mercenaries, while cultivating a literary circle that included J.M. Barrie and Arthur Conan Doyle, who admired his pugnacious and red-blooded writing.

The Great War made things rather more serious for HHP, as it did for the whole world. At 37, he was told he was too old to enlist, so he what he could, working as a Press Officer for the War Office. It was in this capacity that he visited the front lines and saw the horror that was trench warfare. In an effort to redress what he saw as appalling standards among British marksmen, he set up the first Army sniping school. He was able to introduce innovations, such as widespread and accurate telescopic sights, better parapeting, more careful camouflage and observation, and the use of dummy heads to confuse the German snipers. Authorities credited him with saving over 3,500 Allied lives, being awarded the Military Cross for his efforts.

Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard died in 1922, from what is now suspected to be the effects of the malaria he contracted in his travels. He was a man of his times, inevitably, but the breadth of his experiences set him apart from the narrowness that characterised so much of Edwardian society. A fascinating individual.

November 9, 2011

Writers Write: My Favourite Book 2

This is the second in a series of Guest Posts from some of our finest writers. Today, it's Sophie Masson. Sophie has had more than 50 novels published in Australia and internationally, mostly for young adults and children, but also for adults, including the internationally-selling 'Forest of Dreams' .

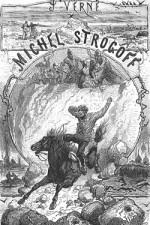

In English-speaking countries, Jules Verne is mainly remembered for his pioneering science-fiction novels: Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, From the Earth to the Moon, and of course his 'science-flavoured' great romp, Around the World in Eighty Days. But Verne also wrote dozens of adventure stories of a more classic kind, set in all sorts of exotic locales, such as Australia and the Pacific (Captain Grant's Children, Mistress Branican) Alaska, China, South America … And, in the 1876 novel, which is reckoned in France to be his very best, the biggest country in the world, Russia.

That novel's simply called, in French (in which language I read it) by the name of its central character, Michel Strogoff (Michael Strogoff, Courier of the Czar, it was titled when translated into English.) And it's the book that amongst all the many favourites of my voracious childhood reading, I've chosen to focus on, because it's had such a big impact on me over the years and set me off on a life-long fascination with the extraordinary culture of an extraordinary land.

When I first read it, aged about eleven or twelve, I already had a few images of Russia, drawn from fairytales I'd loved, such as the Tale of Prince Ivan, Grey Wolf and the Firebird, Fenist the Falcon, The Frog Princess and so on; drawn, too, from my father's great interest in Russian music and Russian icons. But Michel Strogoff, with its passionate, vivid characters, marvellous settings, romance, mystery, danger and adventure — and also a welcome touch of humour — simply bowled me over.

Basically, the story is that Michel (or Mikhail, in Russian) Strogoff, a young Siberian-born soldier in the service of Tsar Alexander II, is sent by the monarch to take a vital, urgent message to the Tsar's brother, who commands the army in Siberia. He has to take the message by hand because a rebel Tartar army under Khan Feofar has cut all telegraph communications with Siberia, prior to taking over towns in the far east. And they're being helped by a traitor called Ivan Ogareff. They plan to lay siege to the Siberian towns and destroy the Tsar's rule there, but Ogareff is in disguise and cannot be found, and the army must be warned. So Michel sets off, by road and river, on a mission which becomes increasingly dangerous as his enemies come to hear of his presence. Meanwhile, his mother is looking for her son—and a young woman named Nadia is on her way to rejoin her father in Siberian exile; and soon enough they meet. Then there's Englishman Harry Blount and Frenchman Alcide Jolivet, rival war correspondents reporting on the upheaval in the empire, who are ready to brave any dangers to get first scoop.

When Michel, his mother and Nadia are captured by the khan's forces, and something terrible happens, all it seems, is lost … But Michel won't give up, not for a moment, and neither will the others …

I read the novel I don't know how many times, swept away by the grandeur of the story, the fantastic adventure, with its wolves, bears, bandits, iced-up rivers, cruel torturers and traitors. I thrilled to the love I could see developing between Nadia and Michel, both equally brave, each in their own way, and I was swept away too by the description of the journey, which starts in Moscow and ends in Siberia — a journey over water, through forest and mountain: you get a real sense of the vastness of Russia, and it was absolutely exhilarating, to me. I guess basically, it's a chase novel, and it has the breakneck pace of that, and lots of twists and turns, culminating in an especially unexpected and satisfyingly resolved one. But it is also beautifully written, as tight and clever as Around the World in Eighty Days, and much more passionate and exciting. No wonder French critics reckon it's Verne's best!

That novel led me directly as a teenager to plunge into actual Russian literature — to Chekhov, Tolstoy,  Dostoevsky, Gogol, Bulgakov, and so on, and it's a passion that has never left me but only deepened and widened with the years, expanding into modern Russian literature of all types including, recently, the wonderful urban fantasy novels of Sergei Lukyanenko (The Night Watch series; and trust me, the books are infinitely better than the films). A few years ago, I wrote a novel based on Russian folklore, The Firebird (Hachette, 1999). Last year too, after decades of dreaming about it, I went to Russia for the first time — an amazing and wonderful trip by water, from Moscow to St Petersburg, stopping at towns and villages along the way. And as I stood on the deck of the boat last year, as we glided serenely down the vast rivers and lakes of Russia, past endless forests and ancient towns, I thought of Michel Strogoff, and how wonderful it was that I'd been brought here, by that book picked up in childhood.

Dostoevsky, Gogol, Bulgakov, and so on, and it's a passion that has never left me but only deepened and widened with the years, expanding into modern Russian literature of all types including, recently, the wonderful urban fantasy novels of Sergei Lukyanenko (The Night Watch series; and trust me, the books are infinitely better than the films). A few years ago, I wrote a novel based on Russian folklore, The Firebird (Hachette, 1999). Last year too, after decades of dreaming about it, I went to Russia for the first time — an amazing and wonderful trip by water, from Moscow to St Petersburg, stopping at towns and villages along the way. And as I stood on the deck of the boat last year, as we glided serenely down the vast rivers and lakes of Russia, past endless forests and ancient towns, I thought of Michel Strogoff, and how wonderful it was that I'd been brought here, by that book picked up in childhood.

It hasn't ended there. That trip last year has only made me all the more addicted to this extraordinary country and its culture, and determined to go again next year, this time as an independent traveller. (To which purpose, after years of shilly-shallying, I'm learning the language too and finding it a good deal easier than I'd thought!) What's more, I've also just finished a big novel set in modern Russia, and I'm about to embark on a second.

And it all started with Michel Strogoff.

Note: Michel Strogoff has been published several times in English, though I think it's out of print now. But it is also available as a free e-book in English, on Project Gutenberg amongst many other sites. In France and other European countries it has also been turned into films and TV series.

Sophie's latest book is 'The Understudy's Revenge' (Scholastic 2011). For more, go to Sophie's Website.

November 3, 2011

November 1, 2011

Writers Write: My Favourite Book 1

This is the first in a series of Guest Posts from some of our finest writers. Today, it's Barry Jonsberg, the writer of the wonderful 'The Whole Business with Kiffo and the Pitbull'.

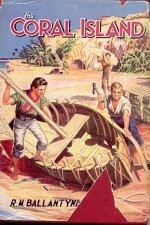

I first read R.M. Ballantyne's The Coral Island when I was about eight years old.

You must remember this was a long time ago. Television was in its infancy and really the only way to explore other worlds was through reading. And read I did. Anything. Everything. In that respect, nothing has changed for me.

I read the book in the way I hope children now read my books – mouth hanging open, jaw slack, so focused on what was happening within the pages that a small nuclear device could have detonated around me and it would have passed unnoticed. The story itself was thrilling. Three boys, Jack, Ralph and Peterkin were marooned on a desert island and had to survive against all the odds. Luckily, food and water were in plentiful supply and they were boys who had spent their young lives at sea, so they were pretty useful with their hands. Within a very short space of time they had made their island home a small paradise and spent leisure time swimming in crystal clear lagoons and generally having the time of their lives. Until a group of cannibals landed on the island and they had to defend the invasion. Then pirates turned up…

The Coral Island is probably best known now for being the book that William Golding based his best-selling novel, Lord Of The Flies, on. Golding had a different take on the situation. In his novel, Ralph, Jack and Piggy experience, not a paradise, but a hell of their own making. The Coral Island showed boys who rose above adversity and became heroes. Lord Of The Flies showed boys who crumbled into savagery and became evil. Both books still hold a special place in my heart.

But a strange thing happened when I re-read The Coral Island as an adult. This time I wasn't completely thrilled by the boys' heroism and goodness. This time I was slightly revolted by the way they were depicted as colonial heroes holding out against nasty natives. They were symbols of British superiority. They didn't feel real.

Is there a moral here? Is it best not to revisit favourite books from childhood in case their magic is revealed as nothing more than smoke and mirrors? After all, the past is a different country. They do things differently there [the opening of another of my favourite books].

What do you think?

Barry's latest book is Queensland Premier's Award winning 'Being Here' (Feb 2011, Allen&Unwin). For more, go to Barry's website. Barry's photo is courtesy of Jen Dainer, Industrial Arc Photography.

October 30, 2011

Talbot Mundy – Adventurous Writer of Adventures

Almost forgotten today, Talbot Mundy was one of the great adventure writers of the first half of the twentieth century. It was fellow bibliophile and curiosity seeker Stephen Bresnehan who put me onto Mundy, sending me a copy of 'King – of the Khyber Rifles', a thrashingly good tale of derring-do in the days of the British Raj. What struck me reading KotKR was the sense of place the story had, how convincing the description was of India, Afghanistan and its people. While some of the characters showed the casual racism of the time, this wasn't universal, and Mundy's portrayal of the Indians and Afghanis was positive, respectful and without condescension. It was evident, too, from the events of the novel, that Mundy was fascinated by the spiritual aspects of life in India and how these differed from Western practices.

Almost forgotten today, Talbot Mundy was one of the great adventure writers of the first half of the twentieth century. It was fellow bibliophile and curiosity seeker Stephen Bresnehan who put me onto Mundy, sending me a copy of 'King – of the Khyber Rifles', a thrashingly good tale of derring-do in the days of the British Raj. What struck me reading KotKR was the sense of place the story had, how convincing the description was of India, Afghanistan and its people. While some of the characters showed the casual racism of the time, this wasn't universal, and Mundy's portrayal of the Indians and Afghanis was positive, respectful and without condescension. It was evident, too, from the events of the novel, that Mundy was fascinated by the spiritual aspects of life in India and how these differed from Western practices.

Intrigued, I went Mundy chasing – and found an extraordinary life.

Talbot Mundy was born in 1879, at the height of the Victorian British Empire, and with a name entirely suited to this era – William Lancaster Gribbon. He attended that most proper of public schools – Rugby – but ran away at the age of sixteen. Two years later he had travelled through Africa, the Middle East, Tibet and China, before spending time in India. He worked with governments, railways and engineering concerns before returning to England in 1909 with a new wife and a new name – Talbot Mundy . The constraints of Edwardian England were only marginally more tolerable to Mundy than Victorian England, so the couple decamped to the US.

Soon, Talbot Mundy was drawing on his travel experiences and writing for the pulp magazines. After some preliminary efforts, he eased into writing historical adventure tales full of colour and dash. He soon gathered a reputation for presenting an alternative to writers such as Sax Rohmer ('Fu Manchu') where 'orientals' were uniformly inferior (at best) or downright evil. While Mundy's protagonists were upright and square-jawed Britons or Americans, they were surrounded by foreigners who were intelligent, capable and with a culture that was indisputably different – and valued for such. His depiction of female characters, too, was notable, as they were often far more forthright and active than was the norm in adventure stories of the time. His Yasmini, from KotKR, for instance is planning to rule India. And not through some ill-defined 'feminine wiles' but through a combination of careful planning, ruthless politicking and targeted demagoguery.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, Mundy became a successful writer, graduating to novels and becoming increasingly interested in philosophical and spiritual matters, in some ways anticipating the interest in Eastern mysticism that flowered in the 1960s. He moved between highly fantastic stories of the occult and gritty historical tales, one series of which ('Tros of Samothrace') was an acknowledged influence on Robert E Howard's 'Conan the Barbarian'.

Talbot Mundy died in 1940. He has been cited as an important influence by writers such as Robert A Heinlein, Leigh Brackett and Fritz Leiber, but if he's remembered today it's often as 'one of those jingoistic imperialist writers', which is doing him a disservice. He deserves to be known as one of the writers of the period who actually visited the places he wrote about, and who actually had affection for and an understanding of, its people.

October 26, 2011

Powerless Heroes

I know this article should really be called 'Powerless Protagonists' or 'Powerless Main Characters' but I couldn't resist the nuance of 'Powerless Heroes'. What I'm talking about is the tendency of many stories to have a main character who is helpless. Put upon. A loser.

I was reading a book the other day – and it shall remain nameless – when I ran into a character like this. He lurched from disaster to disaster. Relationships soured as soon as he touched them, like that milk at the back of the fridge. Businesses went downhill as soon as he joined. Weather became inclement the moment he stepped outside. He was hapless, in the extreme. I think we were meant to feel sorry for him, to sympathise with him as an everyman, but I just grew more and more irritated – and then I had an insight.

You see, it isn't just that he was a victim of circumstance, it was his reaction to all this. Hardship didn't make him stronger, didn't make him more determined – he simply bore it with what was meant to be good grace but came across as peevish whining.

When writing, I maintain that main characters should be powerful in two senses. Firstly, he or she needs to be in a position to act. By that, I mean she or he should be physically able to affect events in the novel. For instance, a hermit, all alone on an island, is probably a poor choice as a protagonist in a story about the wheelings and dealings in political circles in Whitehall, where up and coming crusader Holly Stanthorpe is caught up in a controversy that shows us the seamy side of the historic buildings clique. No, Holly Stanthorpe is better placed to be the main character, instead of poor shipwrecked Ishmael Callaghan, having to read about events by way of the erratic delivery of messages in bottles.

Secondly, your main character should be psychologically able to act. This doesn't have to mean that they are out and out action heroes, ready to disarm the terrorist using materials close at hand, no matter how appealing that might seem. And it doesn't mean that they are successful in their attempts to act, but to drive the novel forward, to engage a reader as an accomplice, the main character should, at some time in the story, make decisions that affect the events unfolding in the narrative.

Without being physically able to act and psychologically able to act, we have main characters who are buffeted about by the seas of fate and destiny. This is all well and good for navigational buoys, but deadly dull if you're a reader – or a writer.

October 23, 2011

Ultimate Teaser

This could be the ultimate 'Extinction Gambit' teaser: my advance copy, nestled in my steely grip.

October 19, 2011

The Extinction Gambit Book Trailer

And here's the official book trailer for my next book 'The Extinction Gambit', Book One of 'The Extraordinaires'.