Susan Price's Blog: Susan Price's Nennius Blog, page 4

July 22, 2016

Hot Beer

There was, at last, a pause in the English monsoon. The sun came out and so we went to Beer. The English are notorious for their warm beer. This Beer was stonking hot. Feel the heat rising off those cobbles.

Near where the concrete path ends and these cobbles begin, a man was talking to two friends. "She said, 'Now you know what child-birth feels like.' I said, 'I don't want to!' But she held my hand, very kind..."

I've never known the sea to be so mirror-still that the cliff's cast such a reflection.

A woman said to a girl of about eleven, "What will your Mum and Dad say when they find out what you've been doing with us?" The girl said, in delighted triumph, "Nothing! I've done nothing!"

Beer competes hard for the village in bloom title. Several doorsteps held enormous scarlet geraniums the size of small bushes. There were window-boxes and hanging baskets and stone pots of marigolds and nasturtiums were part of the street furniture.

The lane leading down to the sea got in on the act too, with valerian, wild carrot, flax, bird's foot trefoil...

People swam, lay on the hot pebbles and watched the little white sail-boats glide past.

"Is it cold?" - "Brass monkeys are diving and weeping, mate."

We went to Sidmouth for the evening. This sandstone cliff beside the river always catches the evening sun.

Next day, Beer was just as hot, but there was a strong breeze. All the flags were horizontal.

Instead of reflecting the cliff, the sea slapped against it and streaks of orange sand could be seen in the water.

But you could turn your back on it and watch the swallows over the cliff.

As you can see, it's not a crowded place.

"Shall we get fish'n'chips and eat them on the beach?"

"Better be ready to fight off the sea gulls."

"Yeah, well, there's no shortage of stones."

But you always have to go home. So we climbed up the cliff path, back to the car and the motorway - and the heat without a sea breeze.

Hope you enjoyed the British summer! Let's hope it lasts a couple of days more.

Published on July 22, 2016 16:00

July 8, 2016

Pond Life

In January this year, we dug a pond. You can see the lovely thing below.

The idea was to make our backyard more enticing to wildlife. A pond is the way to go, apparently, if you're interested in doing that.

We laboured over our hole in the ground for many a day. It was cold. It was muddy. It was unattractive.

Just to make it even more unattractive, we added a black plastic liner. I can't remember if this was the original which sprang a leak after a couple of weeks, or the later one which is still bravely holding water. We weighted the liner down with pots and bricks, to prevent it thrashing about in the frequent gales. In the picture above, it's frozen solid.

Here it is a little further along, still looking unlovely. We've covered some of the liner with earth, and added some plants at the further end. They came from my old pond in a pot (which also sprang a leak and will probably have a tree planted in it at some point.) The pond here is brimming full from the winter downpours. At the moment, it is brimming full from the summer downpours. A couple of weeks ago, the sunshine was so liquid, we had to bale the pond out for fear of flooding.

This picture was taken earlier this week. Those tall, pointed leaves in front of the blue periwinkle are yellow flags donated by Karen Bush aka Madwippit. They are excelling at the tall pointy green leaf bit, but have so far declined to flower. But the wild strawberries Karen gave me are flowering and fruiting. You can just see one of their white flowers above the potted rosemary in the foreground.

Here's one where you can actually see the water.

We were promised that if we did the work and made a pond, we would see more wild-life and the promise has been kept. I have seen more birds in the garden this year than in the past sixteen years I've lived here. Previously, they just flew over, even when I hung feeders out.

There is always a wood pigeon. Whatever kind of food is put out, Woodie is in there first. Here he is yearning after the niger seed which isn't intended for him. But we also have a little family of dunnocks, a wren, a robin, blackbirds, bluetits, great tits, starlings and house-sparrows.

A newcomer was spotted the other day: buff-coloured with marked white wing stripes and a darker head. It's suspected of being a chaffinch, but as yet, this is unconfirmed.

I've become very fond of the sparrows. They love the pond. They come down in a swirl, like falling leaves, and land around its edges, where they drink and bathe.

I'm very fond of this brute - 'Touch Me Not With Impunity' and it tells no lies. I was given this by my auntie, who had put on gauntlets and potted it up for me. It spent the winter lying flat in its pot. Then, one spring day, I noticed that all its spiky leaves had lifted themselves up and were pointing at the sky. So I put on armour and planted it against this wall. Since then, I swear it has grown an inch a week and, when the weather warmed up, a inch a day. It is now as tall as I am and you cannot get near it. In Flann O'Brien's The Third Policeman there is a lance with a point so sharp that its end is invisible and it stabs you while you think it is still inches away. Old Touch Me Not is like that. Its flower buds look soft and velvety but touch one and you leap back across the path with your spiked fingers in your mouth. - But we hope that the seeds will attract more birds.

This is the 'wood' at the top of my garden. There is a dogwood, a crab apple, some towering ferns and lots of brambles. And foxgloves.

The marsh-marigold in the pond. There is a large bud on one of the water-lilies but it's taking an age to open.

I end with Woodie, getting stuck into whatever it was that was scattered on the step. He's the only bird who hangs around long enough to be photographed.

The pond was worth the work. We've had more fun and interest out of it in these past months than almost anything else.

Published on July 08, 2016 16:00

June 24, 2016

History Of The Naked Ape

Reviewed by Susan Price

Warning: This blog is much longer than usual, but it reviews a fascinating book.

Why does the human race - supposedly intelligent - keep fighting wars, despite all that has been said against the habit?

Why do empires, such as the Roman and the British, periodically rise and then fall or fade away?

Why do leaders such as Alexander, Napoleon and Hitler periodically arise to lead their people into war - and why do the people willingly, even eagerly, follow them?

Why has Europe been, for centuries, a 'cockpit of war' and revolution?

Can the EU prevent such 'Wars of Civilisation' in the future?

Why is the continent of Africa riven with war?

Why are so many vicious, murderous political gangs - I could say 'IRA' or 'Baader Meinhof' or 'Daesh' - drawn from the nicely brought up and spoken boys and girls of the middle-classes, who, on the face of it, have comfortable lives and little need to fight for 'freedom'?

And why, in every part of the world and at all times, have the poor always had many more children than the rich, despite being able to afford them less? Why does contraception and education make little difference to this trend?

All these many questions, and more, can be answered very simply. Niche-Space and Breeding Strategy.

This theory is argued by Paul Colinvaux in his 'The Fates of Nations.' He was an ecologist, and The Fates of Nations answers all these questions by applying the rules of ecology, not to salmon or brown bears or wildebeeste, but to that other animal, the Naked Ape.

Colinvaux defines 'niche-space' as 'a specific set of capabilities for extracting resources, for surviving hazards and for competing; coupled with a corresponding set of needs.' It describes not only the amount of physical space an animal requires to live naturally and healthily, but also the animals' requirements in terms of climate, type and amount of food, type and size of home or lair and so on.

Some niche-spaces are larger than others. An acre of land can support many hundreds of deer, if there is enough water and vegetation. It gives them all they need.

However, that same lush, well-watered acre would not support a single tiger. As a dedicated carnivore, a tiger needs access to many, many deer to feed itself. Deer run away from tigers and many are too fast to be caught. Also, all deer become skittish when there's a predator about. In Yellowstone, after the reintroduction of wolves, deer stopped standing about, grazing like cows. Even when the wolf-pack was in an different, distant part of the park, the deer continued to move on frequently, snatching a few mouthfuls here and there, but never staying in one place for very long.

So a tiger needs to be able to shift ground frequently, to find more unsuspecting prey. Every single tiger needs a large territory, which it will defend from others.

As Colinvaux put in in the memorable title of another of his books, this is Why Big Fierce Animals Are Rare. Long before humans became a plague on the earth, before tigers' habitat was remotely threatened, long before they could be efficiently slaughtered for the supposed medicinal value of their bones, even then, tigers were still rare compared to deer or mice or strawberry plants. They were rare because they had a comparatively wide niche-space. Making a living as a tiger demands a lot of resources in terms of space and prey animals.

As Colinvaux put in in the memorable title of another of his books, this is Why Big Fierce Animals Are Rare. Long before humans became a plague on the earth, before tigers' habitat was remotely threatened, long before they could be efficiently slaughtered for the supposed medicinal value of their bones, even then, tigers were still rare compared to deer or mice or strawberry plants. They were rare because they had a comparatively wide niche-space. Making a living as a tiger demands a lot of resources in terms of space and prey animals.

Colinvaux calculates that when humans were living their natural, Ice-Age life, as hunter-gatherers, they were about as common as bears. That is, more common than tigers, because bears and humans are omnivorous and will stoop to eating fruit, vegetables and grubs, but a lot rarer than deer or mice.

That's Niche-Space. Then there's Breeding Strategy.

Every species that has ever lived has always had the same breeding strategy: to have as many off-spring as it's possible to raise to adulthood.

For most animals, this is more or less fixed, so much so that naturalists can write of the 'typical' litter or clutch size for a particular species. This is because an animal's niche-space is usually fixed. As Colinvaux puts it, a squirrel, or any other kind of animal, is 'highly tuned to a very specialized profession.' A squirrel cannot decide that, hey, it would rather be a tiger - any more than a tiger can decide that it would like to try out life as a dolphin.

Evolution has therefore roughly fixed the optimum number of off-spring an animal can have. A very good year may result in birds producing a second clutch of eggs or other animals having a second litter, but that's an exception. In a bad year, when the land can't support the numbers, the animals starve and the population falls. The population of predators is linked to that of their prey. A good year for mice and deer means a good year for wolves and foxes - and vice versa.

Evolution has also fixed the approach most species take to child-rearing: low-investment or high-investment. Low investment species, such as salmon, spawn and fertilise hundreds of eggs at a time. Almost all of them will be eaten, either as eggs or fry. One or two might survive and that's all that matters. The salmon might have made an almighty effort to reach its spawning place but once the eggs are laid, it troubles itself no further about its off-spring.

High-investment species, such as bears, cats and naked apes have one or two off-spring at a time, and they invest a lot of time and effort in feeding and training them. It's a high-risk strategy because, in a bad year, the off-spring might die - or be killed to ensure the survival of older off-spring or the parents. Some animals are known to kill and eat their young if faced with a threat to their own survival. Colinvaux argues that early humans almost certainly regulated their population not only by leaving granny on the ice-flow, but by leaving junior with her. Historically, we know that people frequently abandoned children they did not think they could afford to raise.

Changing Niche SpaceAnimals can't change their niche-space - not by themselves, anyway. Some have become domesticated, some, such as urban foxes, have adapted to living alongside humans, but that came about as a result of human actions

The Naked Ape, however, learned to change its niche-space, and has done so repeatedly.

The Naked Ape, by Desmond Morris First, they were nomadic hunter-gatherers, as common as bears. But they learned to hunt and gather in almost every part of the world - in the Europe of the Ice Ages, in the rain forest and deserts of Australia, in Africa, on Siberian tundra, in the far North of Alaska. In doing so, they increased the niche-space of their species. Instead of being limited to a local population in the tropics, or the temperate regions, naked apes spread to every part of the world except the extreme poles.

The Naked Ape, by Desmond Morris First, they were nomadic hunter-gatherers, as common as bears. But they learned to hunt and gather in almost every part of the world - in the Europe of the Ice Ages, in the rain forest and deserts of Australia, in Africa, on Siberian tundra, in the far North of Alaska. In doing so, they increased the niche-space of their species. Instead of being limited to a local population in the tropics, or the temperate regions, naked apes spread to every part of the world except the extreme poles.

But this spreading population was still limited by the resources available to hunter-gatherers. They followed the high-investment breeding strategy of having one or two children at a time, and spending much time rearing them. As with all other animal species, their population increased during good times, when more children were born and survived - but might crash during bad times when fewer mothers were in condition to give birth and more children died. So the world-wide population increased somewhat, but remained relatively stable.

But then, astonishingly, these animals learned to stop hunting and to herd the animals they needed - whether reindeer, or goats or cattle. They maintained the population of their prey-animals by protecting them from other predators and helping them to find food. This meant that the naked apes themselves could confidently expect to raise more children to adulthood because there was a more certain food supply. Their population increased - and increased again, because it was much less affected by bad years.

Moving from hunter-gatherers to herders meant an increase in niche-space: more resources were available. But, as ever, the increase in resources was soon absorbed by the increased population brought about by the unchanged breeding strategy.

Not to worry, though, because herding led on to settled farming, another huge increase in niche-space. Now, not only were the prey animals kept in one place, protected and provided with food, but the neccessary plant foods were too. Food could be produced more efficiently, and also stored more efficiently when it didn't have to be carried with a nomadic group, or hidden in caches.

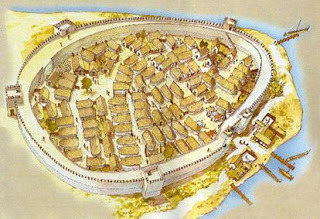

These were huge changes in life-style for the naked ape - but the breeding strategy remained the same. A great many more naked apes were born to take advantage of the niche-space - but more niche-space was also being created by the emergence of city-states and a whole new way of life.

For one, if you could produce more wealth than your neighbour, you could persuade your neighbour to do most of your work for you, in return for a share of your produce. So different classes came into existence.

Why make your own clothes, shoes and pots when it was more efficient to pay someone else to do it, and pay them in money or kind? Some people found that they were good enough at singing or story-telling to make a living at it.

New technologies - the smelting of metals, stone-masonry, ship-building - produced other niche-spaces, absorbing the growing population and allowing them to make a living. A governing class. A priest class. A warrior class. They were all sub-niche-spaces, all provided livings.

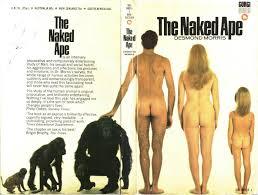

City State - wiki

City State - wiki

Niche Space Runs Out But eventually, as the population grows, there comes pressure on resources. So long as there's enough space in the world to enable more land to be cleared or mined, this isn't a problem. But if there's another growing city-state over there - and another one over there - then the solution is more difficult.

One way of avoiding the problem of shrinking niche-space is to impose a very strict caste or class system. Most societies of Naked Ape have tried this, in some form, at many different times over the centuries. For instance, only males are allowed to do certain jobs, usually high-status jobs, while females have to find a male to support them. Or restrictions may be applied to certain ethnic or religious groups, or simply to 'a lower class' who are deemed 'untouchables' or 'serfs.' This tactic buys time, for a while, but the breeding strategy ensures that the population continues to grow - and, ironically, it's usually among the higher classes where the squeeze of narrowing niche-space is felt first and most painfully, by those children born to affluence who suddenly realise there is no space left for them in the wider, freer niche-space their parents enjoyed.

Another way out of the problem is to trade. You go to those states who are crowding your own, and you offer to exchange surplus goods with them. You can even build ships and cross the seas to trade with foreigners. This, for a while, solves the problem. It creates a source of fresh produce and creates prosperous jobs for many.

But every increase in niche-space means an increase in population - because the breeding strategy rolls on unaltered. Every single person in these growing cities produces as many off-spring as they think they can raise. Up and up goes the population, particuarly among the poorest.

The Poor and Their ChildrenWhy do the poor have more children, even when their more prosperous countrymen crush them into a smaller and smaller niche-space?

'Slum Tourism' - wikipedia Because if you live, say, on a sheet of cloth spread on a pavement, and your biggest aspiration for your children is that they eat once a day, then children are cheap. They aren't going to cost you much - indeed, it will possibly cost you more, in all sorts of ways, to prevent their birth. Children will also start earning for you in infancy, so where is the incentive to limit their number?

'Slum Tourism' - wikipedia Because if you live, say, on a sheet of cloth spread on a pavement, and your biggest aspiration for your children is that they eat once a day, then children are cheap. They aren't going to cost you much - indeed, it will possibly cost you more, in all sorts of ways, to prevent their birth. Children will also start earning for you in infancy, so where is the incentive to limit their number?

If, however, you are rather better off - if your plans for your children include a nursery, then room of their own in a comfortable house, a crib, a nanny, a bed, good clothes and shoes, three or more meals a day, a good education, toys, books, music-lessons, dance-classes, training in a trade, a car (or horse) on their 18th, a good marriage (with a dowry or big wedding) a house of their own, prosperity and children of their own - well, then each child is going to cost you thousands, even tens of thousands. One way or another, you make sure you have fewer. (In ancient Greece and Rome, the well-off exposed children they didn't want to raise.) It's the well-off who sit down with pencil and paper (or Excel) and work out if they can afford a child. The poor, in this as in almost every other life-situation, just get on with it.

Again, it's about niche-space. The niche inhabited by the poor is narrow. It affords them few choices and, as a result, they have few aspirations. But this narrow niche is cheap. It requires few resources. The people crammed into it are satisfied with little. My aunt, who grew up in a slum, has often told me that, until she won a scholarship to grammar-school and discovered that her classmates had electricity and fridges at home, she'd no idea her family were poor, since everyone else she'd known had been equally poor.

The niche-space occupied by the better-off is wider, and increases with wealth. Indeed, Colinvaux remarks that the richer a naked ape is, the more their life includes aspects of the old hunter-gatherer life: - acres of beautiful countryside as their 'territory', travel, hunting as a pastime, dogs and horses. But although this niche is broad, offering many choices and freedoms, it is very expensive in terms of resources. It can, therefore, be occupied by far fewer than the narrow niches of the poor. The poor are like deer - hundreds to the acre. The rich become more tigerish as they grow richer. They defend their territory too.

The niche-space occupied by the better-off is wider, and increases with wealth. Indeed, Colinvaux remarks that the richer a naked ape is, the more their life includes aspects of the old hunter-gatherer life: - acres of beautiful countryside as their 'territory', travel, hunting as a pastime, dogs and horses. But although this niche is broad, offering many choices and freedoms, it is very expensive in terms of resources. It can, therefore, be occupied by far fewer than the narrow niches of the poor. The poor are like deer - hundreds to the acre. The rich become more tigerish as they grow richer. They defend their territory too.

Revolutions and the Middle-Class Herein also lies the answer to the questions: Why are revolutions always led, not by the oppressed, but by the middle-classes? and Why are so many vicious, murderous political gangs drawn from the nicely brought up and spoken boys and girls of those middle-classes?

Delacroix - wikipedia The aspiring and prosperous - from the middle to the upper classes - have always had fewer children than the poor and higher aspirations for the few they have. But the more freedom and choice a niche offers, the more resources it uses and therefore, the fewer people it can support. One child will inherit, and you can give younger sons to the military and the church to find them livings. You can marry some daughters off - but still, if you want your children to remain in your social niche, there's a limit to how many you can find space for. So it's these affluent niches - wide in their choices and freedoms, but narrow in terms of numbers they can contain - which feel the pinch first and most keenly when the pressure on resources mounts.

Delacroix - wikipedia The aspiring and prosperous - from the middle to the upper classes - have always had fewer children than the poor and higher aspirations for the few they have. But the more freedom and choice a niche offers, the more resources it uses and therefore, the fewer people it can support. One child will inherit, and you can give younger sons to the military and the church to find them livings. You can marry some daughters off - but still, if you want your children to remain in your social niche, there's a limit to how many you can find space for. So it's these affluent niches - wide in their choices and freedoms, but narrow in terms of numbers they can contain - which feel the pinch first and most keenly when the pressure on resources mounts.

The very wealthy are insulated by their extreme wealth - and they also have the most resources to use, tigerishly, in defence of what they have. The Military, the Church, the Judiciary, Communications, the Means of Production - almost all of it is in their control. Threaten their position and they will close rank - hence the strong swing to the Right we are experiencing in politics now.

The poorest are used to hardship and never expected much anyway. They're grateful to 'have a roof over their head and a loaf on the table.'

But those caught in the middle, those who grew up expecting that their life would include a comfortable house with a big garden, an interesting, rewarding job, the wherewithal to travel and follow interests, whether it be rock-climbing or pottery - what happens when they find that they are going to have to settle for much less than their parents had? When they find that they can't get a job, can't afford a house, or a car or a holiday - or a child?

It understandably comes as a humiliating, painful shock. And why shouldn't it? After all, nothing about the situation is their fault. They didn't choose the time they were born in, or the way they were raised. Most of them have never even heard of niche-space and breeding strategy and, even if they had, couldn't do anything about it.

When Trade Is Not EnoughSo we've seen that you can increase niche-space by trade and by technological advance - because a new technology, whether it's ship-building or smelting metal, or programming computers, creates jobs.

But, in some periods there comes a point when no new technology is coming to rescue the naked apes from their breeding strategy and trade is no longer supplying enough resources or enough profit to support the growing population. What then?

Then it inevitably occurs to the naked ape that if, instead of trading with a particular country, if they just took the country instead, that would be more profitable.

At any given time, there are always several ambitious apes seeking to be top ape, as apes will. If one of these ambitious apes happens to coincide with a squeeze on niche-space - well, then you have an Alexander, an Augustus, a Clive of India, a Napolean, a Hitler, all of them whole-heartedly supported by their tightly-squeezed countrymen, longing for more niche-space - which answers all those questions about war. Hitler even spoke about 'living-room.'

Being a pacifist feels much more comfortable when your niche-space isn't too tight. (And is much more courageous when it is tight and all around you are in jingo-istic, empire-building mood.)

These 'wars of civilisation,' Colinvaux points out, are always a stronger, more technologically advanced state grabbing a weaker (if not geographically smaller), less advanced, less organised country. Whatever high-flown reason is given, whatever excuse is put forward, it is always a straight-forward bullying snatch of land and resources by the stronger state. There has never been an example of, say, a tribe of Bushmen invading and conquering France or Britain. Barbarians took down Rome, yes - but they were, in fact, highly organised and well-equipped barbarians, quite wealthy in their own opinion - just as Genghis Khan's 'barbarians' were at a later period. In each case the 'barbarians' faced large states exhausted by their efforts to find new niche-space; states that had run out of options.

The option of war and colonisation creates niche-space not only by gaining access to resources such as food and materials at less cost - it also creates interesting and generally well-rewarded jobs for the young of the better-off. They become viceroys and governors of the colonies, merchant-traders, spice-growers, tea-planters, even missionaries. The armies needed to enforce colonisation also provide niche-space for 'the sweepings of the gutter.'

But breeding strategy continues to do its stuff and the new niche-space gained at the cost of war is filled up by the increasing population.

Sometimes, it takes a while. The colonisation of Australia and the Americas (and the genocide of the native civilisation,) siphoned off surplus population and relieved pressure for several centuries. 'Go West, young man.' There will never, Colinvaux remarks, be such a pressure-release valve again.

Why was Europe the 'cockpit of war?'Because there were too many nations crammed into one land mass, their populations increasing and aspiring. Every time the pressure of falling resources was felt, another revolution or war was triggered as the prosperous classes felt the pinch and grew angry.

To win big, final victories and establish an Empire lasting hundreds of years, as the Romans did, you have to go against less well-armed and organised opponents with a tactic they cannot withstand. Alexander won his victories with the phalanx. The Romans had the legion and the tortoise.

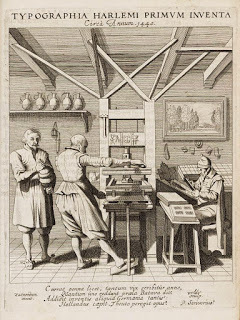

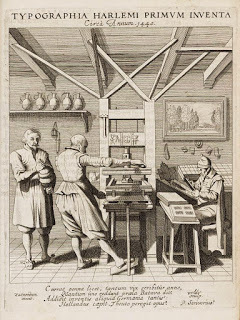

Wikipedia: printing press But in Europe was developed a piece of technology that not only created a lot of niche-space, but meant that no war-like state was going to be able to win crushing, final victories in Europe ever again:- the printing-press. Once the printing-press was invented, any new tactic was, within a few years, available to everyone else. Hence the endless round of revolutions and wars in Europe, which had no direction, not north, west, south or east, to send its restless and disappointed young and no way of winning new niche-space by winning a lasting victory over another European state.

Wikipedia: printing press But in Europe was developed a piece of technology that not only created a lot of niche-space, but meant that no war-like state was going to be able to win crushing, final victories in Europe ever again:- the printing-press. Once the printing-press was invented, any new tactic was, within a few years, available to everyone else. Hence the endless round of revolutions and wars in Europe, which had no direction, not north, west, south or east, to send its restless and disappointed young and no way of winning new niche-space by winning a lasting victory over another European state.

This is also why Africa is riven with so many wars now - and why Europe probably will be again.

Oh, but the European Common Market was created, in part, to prevent war in Europe ever happening again. I had little faith in this argument before I read The Fates of Nations. I have none now. All over Europe are nations seething with people whose niche-space has just crashed in on them, crushing them into a place where they don't want to be. Revolution and war will follow.

In the last couple of months, the IRA have started attacks again. Daesh commit atrocities while journalists confess themselves puzzled that the boys and girls who run away to join Daesh are not only 'middle-class' but appear to know little about Islam. Nor, often, it seems, do the people who recruit them.

That's because it's not, at bottom, about religion or politics. It never was. It is, and always was, about niche-space made tight by breeding strategy.

Left-wingers in the UK at the moment are puzzled and despairing at the political swing to the right - by the fact that the 'Nasty Party' keeps being re-elected, despite their proving, again and again, just how nasty they are. Good-hearted people are dismayed by the increasing xenophobia, the increasing tendency to stigmatise and isolate the poor. They are distressed by the push to turn schools into academies which can refuse admission to pupils who, to be blunt, they consider not good enough and by the push to privatise the NHS, which would take us back to my great-grandparents' age, when one of their children died because sending for a doctor would have cost twelve and a half pence. Which they didn't have to spare.

Colinvaux isn't puzzled. The shift to the right, the hardening of class-barriers, is shrinking niche-space in action. As niche-space shrinks those with the widest niche-space move, like tigers, to protect their territory. They harden their attitude, become more callous, more prejudiced and xenophobic, less open to argument or new ideas. They vote to protect their niche-space.

As the niche-space of others contracts, that of the very wealthy becomes ever wider and more comfortable. We'll soon be back to those good old Victorian Values so beloved of the Tories - when servants were plentiful and cheap, when the lower-classes knew their place and Labour was the lowest cost of production.

Humans have changed their niche-space again and again but, like all other animals, they have never changed their breeding strategy. They stubbornly continue - as they have throughout history - to have as many children as they think they can raise to adulthood within the niche-space they occupy at the time. It's ruinous, to human society and the planet.

We now not only have as many children as we think we can raise, massively increasing demand on resources year on year on year - but we are now occupied in trying to escape death for longer and longer, in trying to ensure that infertile couples can have children too, and in preserving the lives of those who would have naturally died young. The science that enables us to do these things is a niche-space: it provides an interesting living for many. Its researches enable us to increase the population even faster, and to produce more food to feed that growing population. Which ensures that the population will grow even faster still - because breeding-strategy always ensures that niche-space is filled.

I first read Colinvaux's The Fates of Nations over 20 years ago. It lit up my head then, and it does now. I look around, I watch the news, and see the theories of niche-space and breeding-strategy at work everywhere. Indeed, my family are becoming fed-up with hearing me mutter, "Niche-space," at regular intervals.

The book is fascinating. Not cheerful - in fact, rather depressing - but clarifying. Clarity is often depressing.

It's particuarly uncheering for a left-winger like me; but it's hard to deny the truth behind it. The theory doesn't justify war, cruelty, infanticide and so forth. It simply makes clear the pattern that is expressed through them.

In short, a great book if you want to think. But not if you want to sleep easy.

Find Colinvaux's books here.

Postscript. I wrote and scheduled this post before Britain went to the polling-booths to vote on remaining in or leaving the EU. As I write, I don't know what the result will be. But an MP has already been murdered by a man shouting, 'Britons First!' (Niche-space.)

In The Fates of Nations, Colinvaux tries to predict which nation will start the next big war. It won't be any of the usual suspects, he says. It will be a small, crowded island state which 'lives on other nations' territory.' In other words, imports most of its goods. It will happen because the people of this small island state, especially the 'middling-sort' feel thwarted and angry as their niche-space shrinks and as they grow more bitter and disappointed by the failure of their politicians' solutions. It will be begun, he predicts, either by Japan or Great Britain.

Cheers!

Warning: This blog is much longer than usual, but it reviews a fascinating book.

Why does the human race - supposedly intelligent - keep fighting wars, despite all that has been said against the habit?

Why do empires, such as the Roman and the British, periodically rise and then fall or fade away?

Why do leaders such as Alexander, Napoleon and Hitler periodically arise to lead their people into war - and why do the people willingly, even eagerly, follow them?

Why has Europe been, for centuries, a 'cockpit of war' and revolution?

Can the EU prevent such 'Wars of Civilisation' in the future?

Why is the continent of Africa riven with war?

Why are so many vicious, murderous political gangs - I could say 'IRA' or 'Baader Meinhof' or 'Daesh' - drawn from the nicely brought up and spoken boys and girls of the middle-classes, who, on the face of it, have comfortable lives and little need to fight for 'freedom'?

And why, in every part of the world and at all times, have the poor always had many more children than the rich, despite being able to afford them less? Why does contraception and education make little difference to this trend?

All these many questions, and more, can be answered very simply. Niche-Space and Breeding Strategy.

This theory is argued by Paul Colinvaux in his 'The Fates of Nations.' He was an ecologist, and The Fates of Nations answers all these questions by applying the rules of ecology, not to salmon or brown bears or wildebeeste, but to that other animal, the Naked Ape.

Colinvaux defines 'niche-space' as 'a specific set of capabilities for extracting resources, for surviving hazards and for competing; coupled with a corresponding set of needs.' It describes not only the amount of physical space an animal requires to live naturally and healthily, but also the animals' requirements in terms of climate, type and amount of food, type and size of home or lair and so on.

Some niche-spaces are larger than others. An acre of land can support many hundreds of deer, if there is enough water and vegetation. It gives them all they need.

However, that same lush, well-watered acre would not support a single tiger. As a dedicated carnivore, a tiger needs access to many, many deer to feed itself. Deer run away from tigers and many are too fast to be caught. Also, all deer become skittish when there's a predator about. In Yellowstone, after the reintroduction of wolves, deer stopped standing about, grazing like cows. Even when the wolf-pack was in an different, distant part of the park, the deer continued to move on frequently, snatching a few mouthfuls here and there, but never staying in one place for very long.

So a tiger needs to be able to shift ground frequently, to find more unsuspecting prey. Every single tiger needs a large territory, which it will defend from others.

As Colinvaux put in in the memorable title of another of his books, this is Why Big Fierce Animals Are Rare. Long before humans became a plague on the earth, before tigers' habitat was remotely threatened, long before they could be efficiently slaughtered for the supposed medicinal value of their bones, even then, tigers were still rare compared to deer or mice or strawberry plants. They were rare because they had a comparatively wide niche-space. Making a living as a tiger demands a lot of resources in terms of space and prey animals.

As Colinvaux put in in the memorable title of another of his books, this is Why Big Fierce Animals Are Rare. Long before humans became a plague on the earth, before tigers' habitat was remotely threatened, long before they could be efficiently slaughtered for the supposed medicinal value of their bones, even then, tigers were still rare compared to deer or mice or strawberry plants. They were rare because they had a comparatively wide niche-space. Making a living as a tiger demands a lot of resources in terms of space and prey animals.Colinvaux calculates that when humans were living their natural, Ice-Age life, as hunter-gatherers, they were about as common as bears. That is, more common than tigers, because bears and humans are omnivorous and will stoop to eating fruit, vegetables and grubs, but a lot rarer than deer or mice.

That's Niche-Space. Then there's Breeding Strategy.

Every species that has ever lived has always had the same breeding strategy: to have as many off-spring as it's possible to raise to adulthood.

For most animals, this is more or less fixed, so much so that naturalists can write of the 'typical' litter or clutch size for a particular species. This is because an animal's niche-space is usually fixed. As Colinvaux puts it, a squirrel, or any other kind of animal, is 'highly tuned to a very specialized profession.' A squirrel cannot decide that, hey, it would rather be a tiger - any more than a tiger can decide that it would like to try out life as a dolphin.

Evolution has therefore roughly fixed the optimum number of off-spring an animal can have. A very good year may result in birds producing a second clutch of eggs or other animals having a second litter, but that's an exception. In a bad year, when the land can't support the numbers, the animals starve and the population falls. The population of predators is linked to that of their prey. A good year for mice and deer means a good year for wolves and foxes - and vice versa.

Evolution has also fixed the approach most species take to child-rearing: low-investment or high-investment. Low investment species, such as salmon, spawn and fertilise hundreds of eggs at a time. Almost all of them will be eaten, either as eggs or fry. One or two might survive and that's all that matters. The salmon might have made an almighty effort to reach its spawning place but once the eggs are laid, it troubles itself no further about its off-spring.

High-investment species, such as bears, cats and naked apes have one or two off-spring at a time, and they invest a lot of time and effort in feeding and training them. It's a high-risk strategy because, in a bad year, the off-spring might die - or be killed to ensure the survival of older off-spring or the parents. Some animals are known to kill and eat their young if faced with a threat to their own survival. Colinvaux argues that early humans almost certainly regulated their population not only by leaving granny on the ice-flow, but by leaving junior with her. Historically, we know that people frequently abandoned children they did not think they could afford to raise.

Changing Niche SpaceAnimals can't change their niche-space - not by themselves, anyway. Some have become domesticated, some, such as urban foxes, have adapted to living alongside humans, but that came about as a result of human actions

The Naked Ape, however, learned to change its niche-space, and has done so repeatedly.

The Naked Ape, by Desmond Morris First, they were nomadic hunter-gatherers, as common as bears. But they learned to hunt and gather in almost every part of the world - in the Europe of the Ice Ages, in the rain forest and deserts of Australia, in Africa, on Siberian tundra, in the far North of Alaska. In doing so, they increased the niche-space of their species. Instead of being limited to a local population in the tropics, or the temperate regions, naked apes spread to every part of the world except the extreme poles.

The Naked Ape, by Desmond Morris First, they were nomadic hunter-gatherers, as common as bears. But they learned to hunt and gather in almost every part of the world - in the Europe of the Ice Ages, in the rain forest and deserts of Australia, in Africa, on Siberian tundra, in the far North of Alaska. In doing so, they increased the niche-space of their species. Instead of being limited to a local population in the tropics, or the temperate regions, naked apes spread to every part of the world except the extreme poles.But this spreading population was still limited by the resources available to hunter-gatherers. They followed the high-investment breeding strategy of having one or two children at a time, and spending much time rearing them. As with all other animal species, their population increased during good times, when more children were born and survived - but might crash during bad times when fewer mothers were in condition to give birth and more children died. So the world-wide population increased somewhat, but remained relatively stable.

But then, astonishingly, these animals learned to stop hunting and to herd the animals they needed - whether reindeer, or goats or cattle. They maintained the population of their prey-animals by protecting them from other predators and helping them to find food. This meant that the naked apes themselves could confidently expect to raise more children to adulthood because there was a more certain food supply. Their population increased - and increased again, because it was much less affected by bad years.

Moving from hunter-gatherers to herders meant an increase in niche-space: more resources were available. But, as ever, the increase in resources was soon absorbed by the increased population brought about by the unchanged breeding strategy.

Not to worry, though, because herding led on to settled farming, another huge increase in niche-space. Now, not only were the prey animals kept in one place, protected and provided with food, but the neccessary plant foods were too. Food could be produced more efficiently, and also stored more efficiently when it didn't have to be carried with a nomadic group, or hidden in caches.

These were huge changes in life-style for the naked ape - but the breeding strategy remained the same. A great many more naked apes were born to take advantage of the niche-space - but more niche-space was also being created by the emergence of city-states and a whole new way of life.

For one, if you could produce more wealth than your neighbour, you could persuade your neighbour to do most of your work for you, in return for a share of your produce. So different classes came into existence.

Why make your own clothes, shoes and pots when it was more efficient to pay someone else to do it, and pay them in money or kind? Some people found that they were good enough at singing or story-telling to make a living at it.

New technologies - the smelting of metals, stone-masonry, ship-building - produced other niche-spaces, absorbing the growing population and allowing them to make a living. A governing class. A priest class. A warrior class. They were all sub-niche-spaces, all provided livings.

City State - wiki

City State - wikiNiche Space Runs Out But eventually, as the population grows, there comes pressure on resources. So long as there's enough space in the world to enable more land to be cleared or mined, this isn't a problem. But if there's another growing city-state over there - and another one over there - then the solution is more difficult.

One way of avoiding the problem of shrinking niche-space is to impose a very strict caste or class system. Most societies of Naked Ape have tried this, in some form, at many different times over the centuries. For instance, only males are allowed to do certain jobs, usually high-status jobs, while females have to find a male to support them. Or restrictions may be applied to certain ethnic or religious groups, or simply to 'a lower class' who are deemed 'untouchables' or 'serfs.' This tactic buys time, for a while, but the breeding strategy ensures that the population continues to grow - and, ironically, it's usually among the higher classes where the squeeze of narrowing niche-space is felt first and most painfully, by those children born to affluence who suddenly realise there is no space left for them in the wider, freer niche-space their parents enjoyed.

Another way out of the problem is to trade. You go to those states who are crowding your own, and you offer to exchange surplus goods with them. You can even build ships and cross the seas to trade with foreigners. This, for a while, solves the problem. It creates a source of fresh produce and creates prosperous jobs for many.

But every increase in niche-space means an increase in population - because the breeding strategy rolls on unaltered. Every single person in these growing cities produces as many off-spring as they think they can raise. Up and up goes the population, particuarly among the poorest.

The Poor and Their ChildrenWhy do the poor have more children, even when their more prosperous countrymen crush them into a smaller and smaller niche-space?

'Slum Tourism' - wikipedia Because if you live, say, on a sheet of cloth spread on a pavement, and your biggest aspiration for your children is that they eat once a day, then children are cheap. They aren't going to cost you much - indeed, it will possibly cost you more, in all sorts of ways, to prevent their birth. Children will also start earning for you in infancy, so where is the incentive to limit their number?

'Slum Tourism' - wikipedia Because if you live, say, on a sheet of cloth spread on a pavement, and your biggest aspiration for your children is that they eat once a day, then children are cheap. They aren't going to cost you much - indeed, it will possibly cost you more, in all sorts of ways, to prevent their birth. Children will also start earning for you in infancy, so where is the incentive to limit their number? If, however, you are rather better off - if your plans for your children include a nursery, then room of their own in a comfortable house, a crib, a nanny, a bed, good clothes and shoes, three or more meals a day, a good education, toys, books, music-lessons, dance-classes, training in a trade, a car (or horse) on their 18th, a good marriage (with a dowry or big wedding) a house of their own, prosperity and children of their own - well, then each child is going to cost you thousands, even tens of thousands. One way or another, you make sure you have fewer. (In ancient Greece and Rome, the well-off exposed children they didn't want to raise.) It's the well-off who sit down with pencil and paper (or Excel) and work out if they can afford a child. The poor, in this as in almost every other life-situation, just get on with it.

Again, it's about niche-space. The niche inhabited by the poor is narrow. It affords them few choices and, as a result, they have few aspirations. But this narrow niche is cheap. It requires few resources. The people crammed into it are satisfied with little. My aunt, who grew up in a slum, has often told me that, until she won a scholarship to grammar-school and discovered that her classmates had electricity and fridges at home, she'd no idea her family were poor, since everyone else she'd known had been equally poor.

The niche-space occupied by the better-off is wider, and increases with wealth. Indeed, Colinvaux remarks that the richer a naked ape is, the more their life includes aspects of the old hunter-gatherer life: - acres of beautiful countryside as their 'territory', travel, hunting as a pastime, dogs and horses. But although this niche is broad, offering many choices and freedoms, it is very expensive in terms of resources. It can, therefore, be occupied by far fewer than the narrow niches of the poor. The poor are like deer - hundreds to the acre. The rich become more tigerish as they grow richer. They defend their territory too.

The niche-space occupied by the better-off is wider, and increases with wealth. Indeed, Colinvaux remarks that the richer a naked ape is, the more their life includes aspects of the old hunter-gatherer life: - acres of beautiful countryside as their 'territory', travel, hunting as a pastime, dogs and horses. But although this niche is broad, offering many choices and freedoms, it is very expensive in terms of resources. It can, therefore, be occupied by far fewer than the narrow niches of the poor. The poor are like deer - hundreds to the acre. The rich become more tigerish as they grow richer. They defend their territory too.Revolutions and the Middle-Class Herein also lies the answer to the questions: Why are revolutions always led, not by the oppressed, but by the middle-classes? and Why are so many vicious, murderous political gangs drawn from the nicely brought up and spoken boys and girls of those middle-classes?

Delacroix - wikipedia The aspiring and prosperous - from the middle to the upper classes - have always had fewer children than the poor and higher aspirations for the few they have. But the more freedom and choice a niche offers, the more resources it uses and therefore, the fewer people it can support. One child will inherit, and you can give younger sons to the military and the church to find them livings. You can marry some daughters off - but still, if you want your children to remain in your social niche, there's a limit to how many you can find space for. So it's these affluent niches - wide in their choices and freedoms, but narrow in terms of numbers they can contain - which feel the pinch first and most keenly when the pressure on resources mounts.

Delacroix - wikipedia The aspiring and prosperous - from the middle to the upper classes - have always had fewer children than the poor and higher aspirations for the few they have. But the more freedom and choice a niche offers, the more resources it uses and therefore, the fewer people it can support. One child will inherit, and you can give younger sons to the military and the church to find them livings. You can marry some daughters off - but still, if you want your children to remain in your social niche, there's a limit to how many you can find space for. So it's these affluent niches - wide in their choices and freedoms, but narrow in terms of numbers they can contain - which feel the pinch first and most keenly when the pressure on resources mounts.The very wealthy are insulated by their extreme wealth - and they also have the most resources to use, tigerishly, in defence of what they have. The Military, the Church, the Judiciary, Communications, the Means of Production - almost all of it is in their control. Threaten their position and they will close rank - hence the strong swing to the Right we are experiencing in politics now.

The poorest are used to hardship and never expected much anyway. They're grateful to 'have a roof over their head and a loaf on the table.'

But those caught in the middle, those who grew up expecting that their life would include a comfortable house with a big garden, an interesting, rewarding job, the wherewithal to travel and follow interests, whether it be rock-climbing or pottery - what happens when they find that they are going to have to settle for much less than their parents had? When they find that they can't get a job, can't afford a house, or a car or a holiday - or a child?

It understandably comes as a humiliating, painful shock. And why shouldn't it? After all, nothing about the situation is their fault. They didn't choose the time they were born in, or the way they were raised. Most of them have never even heard of niche-space and breeding strategy and, even if they had, couldn't do anything about it.

When Trade Is Not EnoughSo we've seen that you can increase niche-space by trade and by technological advance - because a new technology, whether it's ship-building or smelting metal, or programming computers, creates jobs.

But, in some periods there comes a point when no new technology is coming to rescue the naked apes from their breeding strategy and trade is no longer supplying enough resources or enough profit to support the growing population. What then?

Then it inevitably occurs to the naked ape that if, instead of trading with a particular country, if they just took the country instead, that would be more profitable.

At any given time, there are always several ambitious apes seeking to be top ape, as apes will. If one of these ambitious apes happens to coincide with a squeeze on niche-space - well, then you have an Alexander, an Augustus, a Clive of India, a Napolean, a Hitler, all of them whole-heartedly supported by their tightly-squeezed countrymen, longing for more niche-space - which answers all those questions about war. Hitler even spoke about 'living-room.'

Being a pacifist feels much more comfortable when your niche-space isn't too tight. (And is much more courageous when it is tight and all around you are in jingo-istic, empire-building mood.)

These 'wars of civilisation,' Colinvaux points out, are always a stronger, more technologically advanced state grabbing a weaker (if not geographically smaller), less advanced, less organised country. Whatever high-flown reason is given, whatever excuse is put forward, it is always a straight-forward bullying snatch of land and resources by the stronger state. There has never been an example of, say, a tribe of Bushmen invading and conquering France or Britain. Barbarians took down Rome, yes - but they were, in fact, highly organised and well-equipped barbarians, quite wealthy in their own opinion - just as Genghis Khan's 'barbarians' were at a later period. In each case the 'barbarians' faced large states exhausted by their efforts to find new niche-space; states that had run out of options.

The option of war and colonisation creates niche-space not only by gaining access to resources such as food and materials at less cost - it also creates interesting and generally well-rewarded jobs for the young of the better-off. They become viceroys and governors of the colonies, merchant-traders, spice-growers, tea-planters, even missionaries. The armies needed to enforce colonisation also provide niche-space for 'the sweepings of the gutter.'

But breeding strategy continues to do its stuff and the new niche-space gained at the cost of war is filled up by the increasing population.

Sometimes, it takes a while. The colonisation of Australia and the Americas (and the genocide of the native civilisation,) siphoned off surplus population and relieved pressure for several centuries. 'Go West, young man.' There will never, Colinvaux remarks, be such a pressure-release valve again.

Why was Europe the 'cockpit of war?'Because there were too many nations crammed into one land mass, their populations increasing and aspiring. Every time the pressure of falling resources was felt, another revolution or war was triggered as the prosperous classes felt the pinch and grew angry.

To win big, final victories and establish an Empire lasting hundreds of years, as the Romans did, you have to go against less well-armed and organised opponents with a tactic they cannot withstand. Alexander won his victories with the phalanx. The Romans had the legion and the tortoise.

Wikipedia: printing press But in Europe was developed a piece of technology that not only created a lot of niche-space, but meant that no war-like state was going to be able to win crushing, final victories in Europe ever again:- the printing-press. Once the printing-press was invented, any new tactic was, within a few years, available to everyone else. Hence the endless round of revolutions and wars in Europe, which had no direction, not north, west, south or east, to send its restless and disappointed young and no way of winning new niche-space by winning a lasting victory over another European state.

Wikipedia: printing press But in Europe was developed a piece of technology that not only created a lot of niche-space, but meant that no war-like state was going to be able to win crushing, final victories in Europe ever again:- the printing-press. Once the printing-press was invented, any new tactic was, within a few years, available to everyone else. Hence the endless round of revolutions and wars in Europe, which had no direction, not north, west, south or east, to send its restless and disappointed young and no way of winning new niche-space by winning a lasting victory over another European state.This is also why Africa is riven with so many wars now - and why Europe probably will be again.

Oh, but the European Common Market was created, in part, to prevent war in Europe ever happening again. I had little faith in this argument before I read The Fates of Nations. I have none now. All over Europe are nations seething with people whose niche-space has just crashed in on them, crushing them into a place where they don't want to be. Revolution and war will follow.

In the last couple of months, the IRA have started attacks again. Daesh commit atrocities while journalists confess themselves puzzled that the boys and girls who run away to join Daesh are not only 'middle-class' but appear to know little about Islam. Nor, often, it seems, do the people who recruit them.

That's because it's not, at bottom, about religion or politics. It never was. It is, and always was, about niche-space made tight by breeding strategy.

Left-wingers in the UK at the moment are puzzled and despairing at the political swing to the right - by the fact that the 'Nasty Party' keeps being re-elected, despite their proving, again and again, just how nasty they are. Good-hearted people are dismayed by the increasing xenophobia, the increasing tendency to stigmatise and isolate the poor. They are distressed by the push to turn schools into academies which can refuse admission to pupils who, to be blunt, they consider not good enough and by the push to privatise the NHS, which would take us back to my great-grandparents' age, when one of their children died because sending for a doctor would have cost twelve and a half pence. Which they didn't have to spare.

Colinvaux isn't puzzled. The shift to the right, the hardening of class-barriers, is shrinking niche-space in action. As niche-space shrinks those with the widest niche-space move, like tigers, to protect their territory. They harden their attitude, become more callous, more prejudiced and xenophobic, less open to argument or new ideas. They vote to protect their niche-space.

As the niche-space of others contracts, that of the very wealthy becomes ever wider and more comfortable. We'll soon be back to those good old Victorian Values so beloved of the Tories - when servants were plentiful and cheap, when the lower-classes knew their place and Labour was the lowest cost of production.

Humans have changed their niche-space again and again but, like all other animals, they have never changed their breeding strategy. They stubbornly continue - as they have throughout history - to have as many children as they think they can raise to adulthood within the niche-space they occupy at the time. It's ruinous, to human society and the planet.

We now not only have as many children as we think we can raise, massively increasing demand on resources year on year on year - but we are now occupied in trying to escape death for longer and longer, in trying to ensure that infertile couples can have children too, and in preserving the lives of those who would have naturally died young. The science that enables us to do these things is a niche-space: it provides an interesting living for many. Its researches enable us to increase the population even faster, and to produce more food to feed that growing population. Which ensures that the population will grow even faster still - because breeding-strategy always ensures that niche-space is filled.

I first read Colinvaux's The Fates of Nations over 20 years ago. It lit up my head then, and it does now. I look around, I watch the news, and see the theories of niche-space and breeding-strategy at work everywhere. Indeed, my family are becoming fed-up with hearing me mutter, "Niche-space," at regular intervals.

The book is fascinating. Not cheerful - in fact, rather depressing - but clarifying. Clarity is often depressing.

It's particuarly uncheering for a left-winger like me; but it's hard to deny the truth behind it. The theory doesn't justify war, cruelty, infanticide and so forth. It simply makes clear the pattern that is expressed through them.

In short, a great book if you want to think. But not if you want to sleep easy.

Find Colinvaux's books here.

Postscript. I wrote and scheduled this post before Britain went to the polling-booths to vote on remaining in or leaving the EU. As I write, I don't know what the result will be. But an MP has already been murdered by a man shouting, 'Britons First!' (Niche-space.)

In The Fates of Nations, Colinvaux tries to predict which nation will start the next big war. It won't be any of the usual suspects, he says. It will be a small, crowded island state which 'lives on other nations' territory.' In other words, imports most of its goods. It will happen because the people of this small island state, especially the 'middling-sort' feel thwarted and angry as their niche-space shrinks and as they grow more bitter and disappointed by the failure of their politicians' solutions. It will be begun, he predicts, either by Japan or Great Britain.

Cheers!

Published on June 24, 2016 16:00

June 3, 2016

Stick Island

On our latest trip to Mull, we did what tourists to Mull have been doing for over 300 years - we paid locals with a boat to take us out to the island of Staffa.

I'd heard of Staffa, of course. I was raised by a man fascinated by geology, for one thing. I knew that Mendelssohn had been so gob-smacked by it that he wrote 'Fingal's Cave' and the Hebrides Overture. I was keen to go and see it.

But you know what they say about film and photographs never doing justice to a place? That's true of Staffa, cubed. When the boat came alongside the island, under the cliffs - well, I damn near wrote an overture.

None of these photos, let me make it clear, even begin to do justice to this amazing, numinous place.

It has no safe anchorage. We went ashore, but were only able to because the weather was extremely good and the sea calm. The skipper told us that if the sea is at all choppy, it's impossible to land.

The name of the island is Norse. The 'a' at the end is common in Norse and Saxon place-names. The 'y' at the end of Ely is the same word. Barra, Ulva, Canna - the 'a' at the end of them all means 'island.'

The 'Staff' part can be translated in various ways, but it's come down to us as the word 'staff' or 'stave' - so the boat's skipper wasn't wrong when he translated it as 'Stick Island.' Others translate it as 'pillar' and say the Vikings were reminded of the wooden pillars that supported their houses.

Imagine being a viking, though, and passing this place, this strange concoction of stone rising straight out of the sea, unlike any other place on earth. Why did the gods create it?

There are three layers to Staffa. There's the smooth, beige-brown rock at the bottom. That's volcanic lava, or tuff. It's volcanic ash, consolidated into rock.

The second layer, those spectacular sticks, is black basalt - a great, thick layer of black basalt - which has cooled slowly. This slow cooling caused it to contract and take on this crystalline structure of hexagonal columns.

Above the columns is a sort of wild top-knot of solid rock. That's not turf or grass you're looking at, but basalt.

Coming in to the jetty

Coming in to the jettyPresumably, this basalt cooled much faster and didn't crystallise. Instead there's this wild tangle of half-formed columns and dabs and dobs and rocks that looks as if it's been frothed up with a whisk. It bulges in places like the top of a muffin, but it's solid basalt.

If you're reminded of the Giant's Causeway, that's not surprising. Staffa was produced by the same eruption that produced the Causeway and there are similar, but smaller, pillared cliffs all over Mull, often producing an oddly striped, humbug effect on mountainsides.

According to legend, an Irish giant built the Causeway, so he could cross the Irish Sea and beat up a Scottish giant on the other side. It turned out, thought, that the Scots giant was much bigger and fiercer than expected, and so the Irish giant tore up his own causeway in a panic, to prevent the Scots giant reaching him. Staffa is all that's left of the Scottish end.

I can believe it. Lots of people have made that mistake when tangling with Scots. Best leave them alone and never, ever poke them sticks.

Staffa has a tiny wooden jetty against one cliff, where the boat tied up. I don't like to think about who built this jetty or how they managed it. (Where did they stand? Where did they put down their tools?)

From the jetty a metal staircase goes straight up the cliff, almost vertically. Occasionally, it uses the flat tops of basalt columns in place of steps. I had to almost run up these steps because I was first out of the boat and had to keep ahead of everyone else. I reached the top more dead than alive - to be greeted by a massed choir of skylarks, which revived me.

A primrose on Staffa

A primrose on StaffaI think that's Rhum on the horizon.

Celendine and violets - I leave you to imagine the sky-larks singing above.

Celendine and violets - I leave you to imagine the sky-larks singing above.I was promised puffins, but the puffins saw us coming and $%"* off into the sea. They must get fed up of tourists. There were some skuas bullying peewits.The skylarks avoided all that by staying in the upper atmosphere and carpet-bombing with song.

The island is now owned by the National Trust but people did once live on it. I can hardly believe this, but there were the remains of fields to be seen and when Sir Joseph Banks visited in 1772, he stayed at the only house on the island, and caught lice. The single family who farmed on Staffa lived on oats, potatoes and the milk and meat of their few grazing animals. By 1800, 'terrified of the winter storms,' they'd given up and I don't blame them.

Staffa's cliffs

Staffa's cliffsWe had an hour on the island, which is about a kilometre or half-mile long and half that wide. What must it have been like to live, perched up on top of that rock, with no company other than your immediate family? - We were lucky, we could enjoy it for an hour and then leave. We scrambled back down that dizzy staircase into the boat. As the boat turned back for Mull and Iona, we passed Am Buachaille, The Herdsman.

If you squint at this shot, below, you may be able to see some puffins scattered about. I am told they are there. I can't see them.

I listened to Mendelssohn's 'Fingal's Cave' when I got back to civilisation. I don't think he did the place justice any more than my photos do.

It was an exhilarating trip but saddening too, because I kept wishing my Dad had been there. He would have known about all the geology and all the birds and plants too. He would have been fit to be tied. We would have had to set traps to get him back on the boat. So, this blog's for Dad.

Published on June 03, 2016 16:00

May 20, 2016

"There's A High Over Scandinavia..."

That's me and Davy, leaning on the quayside at Oban as the sun sets over the bay and the mountains of Mull. It is, honest. Oh well, okay then, it isn't. It's a random young couple who happened to get between me and my camera.

Davy, with his usual weather eye, announced that there was a high over Scandinavia and the weather was going to be unusually good in the Western Isles. So we hurriedly packed, dashed up the motorways early on Sunday morning and spent the evening in Oban.

The next morning we took one of the good old Callie-Macs out to Craignure on Mull.

The crossing only takes 45 minutes. As we neared Craignure, we passed Castle Duart.

On previous visits to Mull we've investigated Grass Point, where the drovers used to bring their cattle, to ship them over to Kerrara and the mainland; and we've driven down the Ross of Mull to catch the ferry over to Iona. But, on this trip, Davy was interested in seeing the beaches on the Ross of Mull. He'd picked up, from somewhere, that they were reckoned to be 'the finest beaches in the UK.'

I'll say this much: they're not at all bad.

An equally fine beach is on the North of the island, at Calgary. It was all pure white sand, empty blue sky and a sea of a pale blue impossible to describe. Icy cold, though. The sea, that is. The beach was hot.

This isn't Calgary - it's one of the Ross of Mull beaches, because my camera's battery had run out by the time we got to Calgary and I somehow managed to forget all electronics. I suspect it was a kind of accidentally-on-purpose sort of forgetfulness.

This isn't Calgary - it's one of the Ross of Mull beaches, because my camera's battery had run out by the time we got to Calgary and I somehow managed to forget all electronics. I suspect it was a kind of accidentally-on-purpose sort of forgetfulness.Calgary in Canada, by the way, is named after Calgary on Mull. A chief of mounties, apparently, used to spend his holidays at Calgary on Mull, and when a name was needed for a new fort in Canada, he suggested 'Calgary.' The little village on Mull's name is really Gaelic: Cala ghearraidh, or beach of the meadow pasture.

The amazing pink rock you find on Iona and Mull.

We stayed at the Argyll Arms in the village of Bunessan. It could not have been better. The road ran right past the pub's door but was hardly busy. On the other end of the narrow road was a bay, with a view out to Staffa. The staff were friendly, the room comfortable and the food good.

Almost all the roads on Mull are single-lane, with passing-places. Driving them is a strain. You have to be constantly watching for vehicles miles ahead and calculating whether or not to pull into the passing-place nearest to you. There are always plenty of drivers who seem incapable of grasping the idea of passing-places and drive right up to your car's nose and impatiently wave at you, to tell you to reverse. They do this, even when there is a passing-place directly behind them which they have driven right past. They think you should reverse around a blind bend with rocks to one side and a drop into a loch on the other rather than they reverse a couple of metres in a straight line.

Amazingly, when a police-car is on the road, all the drivers suddenly seem to understand passing-places.

But not the eagle-watchers who park their cars in passing-places and set up telescopes on tripods, to keep watch on some distant peak.

Davy and I saw eagles. We had walked up one of the island's roads less travelled, and Davy pointed and said, "What's that?" I looked and, gentle readers, honestly thought I saw a glider heading towards us. (My eyesight is not the best.) "Eagles," Davy said. I suppose if we'd had binoculars, we could have told whether they were golden eagles or sea-eagles, but eagles they certainly were. Too ruddy big to be anything else.

But the driving. To reach Oban, Davy drove 300 miles, with only a couple of short breaks. He said that was easier, and less strain, than driving the 50 miles from Bunnessan to Calgary.

A man with sense enough to bring co-drivers.

A man with sense enough to bring co-drivers.

I loved our time getting sun-burned in the Hebrides but, for me, the highlight was a boat-trip to island of Staffa.

I shall save that for another blog.

Published on May 20, 2016 16:00

May 6, 2016

The Sterkarms Spake Like Th'Owd Uns

There was a Black Country man who was famous for his inventive

A Sterkarm Tryst by Susan Pricecursing. He could curse for half an hour without drawing breath or repeating himself.

A Sterkarm Tryst by Susan Pricecursing. He could curse for half an hour without drawing breath or repeating himself.

One day he misjudged his aim and gave his thumb a good wallop with his hammer. His workmates paused in their own work and waited with interest. He said, "Oh - faddle!"

His workmates stared. Then one said,

"Tha coo-ert cuss as tha couldst cuss, cost?"

This tongue-twister is an old Black Country story, handed down to me. An heirloom story. The final line is, of course, in Black Country dialect and translates as:

"Thou canst not curse as thou couldst curse, canst thou?"

In translation, it becomes quite Shakespearean. As, of course, it is, since the Black Country dialect, like many other despised English dialects, preserves a lot of older English.

What has this to do with the Sterkarms?

Well, one of the things I've been doing as I've rewritten the Sterkarms over the past year, is to make the Sterkarm's speech more archaic. So I've been grappling with one of the big, perennial problems of writing historical fiction. How do you represent the speech of historical characters?

One school of thought is that you have your characters speak in modern English because the people of the past didn't think of themselves as being 'historical.' They were right up to the minute fashionistas, and they spoke right-up-to-the-minute Latin, or Aramaic, or Anglo-Norman or whatever.

Red Shift by Alan Garner I have a lot of sympathy with that point of view. It was handled superbly in Alan Garner's Red Shift, where one section opens with a conversation between, at first glance, American GIs during the Vietnam War. Only gradually do we realise that they are, in fact, Roman legionaries stranded 'behind the lines' in darkest Celtic Britain.

Red Shift by Alan Garner I have a lot of sympathy with that point of view. It was handled superbly in Alan Garner's Red Shift, where one section opens with a conversation between, at first glance, American GIs during the Vietnam War. Only gradually do we realise that they are, in fact, Roman legionaries stranded 'behind the lines' in darkest Celtic Britain.

After all, the legionaires would have had their own slang, the equivalent of that used by soldiers in later wars. I read somewhere that a lot of our 'classical' Latin is, in fact, slang, that 'caput' actually means, not 'head' but the stopper for a jar. How true this is, I can't say, being no linguist, but it's an interesting idea. The slang of one period becomes the revered classical prose of another. At sometime in the future, 'Hey dude, wassup?' will be heard or read as, 'Dear sir, respectful greetings.'

So I could have made the Sterkarms talk in modern English - except that, in these books, 21st Century characters and 16th Century characters are together in the same time and space, via a time-machine.

I used to love the old SF series, The Time Tunnel. I've always loved the fantasy of being able to visit other times and experience what life was like then. But even as a child, it irritated me that wherever our time-travellers stepped out of their machine - whether it was Ancient Greece or Revolutionary France - they could instantly understand the locals, and the locals them. Perhaps the From Wikipediaseries came up with some explanation, similar to Douglas Adam's brilliant 'babel fish,' but if it did, I missed it.

From Wikipediaseries came up with some explanation, similar to Douglas Adam's brilliant 'babel fish,' but if it did, I missed it.

I was determined not to make that mistake when I wrote the Sterkarms, and made it very clear that the Sterkarm's speech is not immediately understandable to their 21st Century visitors, nor vice-versa.