Susan Price's Blog: Susan Price's Nennius Blog, page 3

March 24, 2017

A Review of A Sterkarm Tryst by Penny Dolan

Penny Dolan is a wonderful writer whose books include the gripping and beautiful romp,

Penny Dolan is a wonderful writer whose books include the gripping and beautiful romp,  Susan Price’s long-awaited YA novel

A STERKARM TRYST

has now been published. So, because I loved the world of the 16th Century Border Reivers that was brilliantly evoked in the two earlier titles -

THE STERKARM HANDSHAKE

and

A STERKARM KISS

- I bought a copy of this third novel, and was not disappointed. Earlier events and confrontations are woven lightly into the plot, allowing new readers and re-readers slip easily into this particular storyline. This is science fiction with excellent time-travelling!The trilogy has an interesting premise: James Windsor, a late 21stCentury entrepreneur, intended to use his company’s Time Tube to colonise and exploit the unspoilt lands of the past. Windsor thought his men would easily secure such a backward territory - and then they met the Sterkarms. Of all the feuding families in the Debatable Lands, the Sterkarms are the most treacherous: everyone knows that a Sterkarm handshake might promise friendship with the right hand while the left hand carries a blade to slide between your ribs. At first, the Sterkarms treat the 21st century intruders with wary respect, deciding these strangers must be Elves. After all, they can appear and disappear, dress in unknown materials, and carry magic pills that take away pain. And from these "Elvenkind" springs the relationship that stands at the heart of the novels. Andrea Mitchell, a 21st Century anthropologist, finds the love of her life in Per Sterkarm, the family heir, and at the start of THE STERKARM TRYST, she has come through time to her lover again, though uncertain of any welcome. Known as his "Entraya", his Elf-May, she has a hard task. She has to warn Per and the Sterkarm family that a deadly new enemy has entered their lands. Windsor has time-travelled a group of Sterkarms from an almost parallel time dimension into this one. These are warriors who know this wild landscape as they do, and who fight with matching ferocity and who look just as they do. They will know all the Sterkarm tricks, and Windsor is behind them.

How can Andrea even explain this phenomenon?

How can a Sterkarm attack another to whom - it seems - they owe loyalty?

And how, I wondered, can a writer manage two almost-identical casts?Susan Price does. Carefully, scene by scene, she moves the action forward, resolving what the reader wants resolved, and ending with treachery getting what it deserves. The headings keep the story straight and satisfying in its conclusions.However, I must say that the plot was not the only thing that made A STERKARM TRYST a compelling experience for me. Within the storytelling, I heard rich echoes of the traditions, superstitions and legends of the Border Ballads, as well as the languages and voices of the region and its past. Humour is there too, within the pages, as well as moments when the differences between the present and the past are suddenly very evident.Moreover, the dramatic landscape of the book is recognisably that of the Borders, an area of wild uplands and uncertain weather, a place where cattle-raids were then part of the culture, and where hunger was a constant threat. I enjoyed being within that way of life, following the descriptions of an active community and culture, along with glimpses of cooking methods, housekeeping and textiles, herbal lore, fear and superstition. Captured in the writing too, was the importance of respectful behaviour and right words and acting according to your status: the sense of a time and place where any perceived insult might mean death. A STERKARM TRYST feels a very physical story. It moves through camps and hovels and crowded stone towers, past the stink of unwashed clothes and the gutting of meat and the hard lives and gory deaths of men and women: this is not a benign or moral fairy-tale. Besides, survival depends on a reputation for cunning and treachery, especially when there are two lots of Sterkarms riding out, as well as Windsor’s thugs and their 21st Century weapons. Yet, reading the book from the comfort of home - and despite all the violence - it is hard not to admire the warmth and energy and the bonds of family loyalty and protection within the Sterkarm clan. Like Andrea/Entraya, I found the Sterkarms beguiling, and welcomed the many characters that Susan Price has created – Toorkild, Lady Isobel, Sweet Milk, Gobby, Mistress Crosar, Joan Grannam, Davy, Cho and more - each one entirely convincing, for all their faults.

Especially that blue-eyed, fair-haired hero, Per May Sterkarm. And Cuddy. I have to mention them. Read the book and you’ll discover why.

Penny Dolan.

Susan Price’s long-awaited YA novel

A STERKARM TRYST

has now been published. So, because I loved the world of the 16th Century Border Reivers that was brilliantly evoked in the two earlier titles -

THE STERKARM HANDSHAKE

and

A STERKARM KISS

- I bought a copy of this third novel, and was not disappointed. Earlier events and confrontations are woven lightly into the plot, allowing new readers and re-readers slip easily into this particular storyline. This is science fiction with excellent time-travelling!The trilogy has an interesting premise: James Windsor, a late 21stCentury entrepreneur, intended to use his company’s Time Tube to colonise and exploit the unspoilt lands of the past. Windsor thought his men would easily secure such a backward territory - and then they met the Sterkarms. Of all the feuding families in the Debatable Lands, the Sterkarms are the most treacherous: everyone knows that a Sterkarm handshake might promise friendship with the right hand while the left hand carries a blade to slide between your ribs. At first, the Sterkarms treat the 21st century intruders with wary respect, deciding these strangers must be Elves. After all, they can appear and disappear, dress in unknown materials, and carry magic pills that take away pain. And from these "Elvenkind" springs the relationship that stands at the heart of the novels. Andrea Mitchell, a 21st Century anthropologist, finds the love of her life in Per Sterkarm, the family heir, and at the start of THE STERKARM TRYST, she has come through time to her lover again, though uncertain of any welcome. Known as his "Entraya", his Elf-May, she has a hard task. She has to warn Per and the Sterkarm family that a deadly new enemy has entered their lands. Windsor has time-travelled a group of Sterkarms from an almost parallel time dimension into this one. These are warriors who know this wild landscape as they do, and who fight with matching ferocity and who look just as they do. They will know all the Sterkarm tricks, and Windsor is behind them.

How can Andrea even explain this phenomenon?

How can a Sterkarm attack another to whom - it seems - they owe loyalty?

And how, I wondered, can a writer manage two almost-identical casts?Susan Price does. Carefully, scene by scene, she moves the action forward, resolving what the reader wants resolved, and ending with treachery getting what it deserves. The headings keep the story straight and satisfying in its conclusions.However, I must say that the plot was not the only thing that made A STERKARM TRYST a compelling experience for me. Within the storytelling, I heard rich echoes of the traditions, superstitions and legends of the Border Ballads, as well as the languages and voices of the region and its past. Humour is there too, within the pages, as well as moments when the differences between the present and the past are suddenly very evident.Moreover, the dramatic landscape of the book is recognisably that of the Borders, an area of wild uplands and uncertain weather, a place where cattle-raids were then part of the culture, and where hunger was a constant threat. I enjoyed being within that way of life, following the descriptions of an active community and culture, along with glimpses of cooking methods, housekeeping and textiles, herbal lore, fear and superstition. Captured in the writing too, was the importance of respectful behaviour and right words and acting according to your status: the sense of a time and place where any perceived insult might mean death. A STERKARM TRYST feels a very physical story. It moves through camps and hovels and crowded stone towers, past the stink of unwashed clothes and the gutting of meat and the hard lives and gory deaths of men and women: this is not a benign or moral fairy-tale. Besides, survival depends on a reputation for cunning and treachery, especially when there are two lots of Sterkarms riding out, as well as Windsor’s thugs and their 21st Century weapons. Yet, reading the book from the comfort of home - and despite all the violence - it is hard not to admire the warmth and energy and the bonds of family loyalty and protection within the Sterkarm clan. Like Andrea/Entraya, I found the Sterkarms beguiling, and welcomed the many characters that Susan Price has created – Toorkild, Lady Isobel, Sweet Milk, Gobby, Mistress Crosar, Joan Grannam, Davy, Cho and more - each one entirely convincing, for all their faults.

Especially that blue-eyed, fair-haired hero, Per May Sterkarm. And Cuddy. I have to mention them. Read the book and you’ll discover why.

Penny Dolan.

All three titles, including THE STERKARM TRYST , are published by OpenPress in a handsomely-matching set of covers or as e-books.

Return to REVIEWS HOMEPAGE

Published on March 24, 2017 17:00

February 16, 2017

Hailing Far Spring...

Valentine's Day is when the birds do choose their make.Right enough, action in the garden is hotting up.

Valentine's Day is when the birds do choose their make.Right enough, action in the garden is hotting up. Here's my garden, in a picture taken last year.

It is so bleak and grey and cold out there at the moment - except for one bright clump of primroses at the end of the pond which have never stopped flowering. But shoots are coming up everywhere: all over the garden and in pots. I can't tell you how much I'm looking forward to them flowering.

The pond we dug out last January has been wonderfully successful in increasing the number of visiting birds. Before we had zero. Now they come winging in every single day. We have our own little colony of sparrows and before, I never appreciated how acrobatic they are. They hover at the feeders while trying to find a place. They chase each other round them. Today I saw a couple doing loop-the-loops around each other in mid-air. They reguarly come down in a mob to drink at the pool's edge and bathe, even on the coldest day.

We've got used to the fact that the birds resent our presence in the garden. If we linger over tasks, they crowd the trees and yell at us. If we persist, they drop down to slightly nearer branches and yell louder. I've come to recognise the peculiar whistling whoop that starlings make and the craak-craak-craak of magpies. The moment we step back inside the house, they come down to the pond and feeders in flocks before we can pull the door shut.

The magpies swagger about, wearing their gangster black-and-white. Until I saw them close up and so often, I never realised what an iridescent shimmer of petrol blue runs over their black feathers.

The of starlings come in gangs of five and seven, with wicked beaks like stilettos, and frantically fight to get into small hanging bird tables and squabble with the sparrows over the spaces on the feeders. Or they plummet down and raid the ground-feeder.

There is a tiny wren that we see more and more often as Spring approaches. It drank from the pond today, a tiny little ball on the edge of a slate. It searched the rose bush above the pond and walks

Wren: Dibyendu Ash, wikimediavertically up walls, investigating the slight crevices between bricks. A couple of days ago it was right by the patio doors, pecking away at something invisible and taking no notice of us.

Wren: Dibyendu Ash, wikimediavertically up walls, investigating the slight crevices between bricks. A couple of days ago it was right by the patio doors, pecking away at something invisible and taking no notice of us.Woodpigeons, robins, blackbirds, bluetits and dunnocks visit us reguarly. The bluetit, yesterday, perched on the very highest twig of the leafless lilac and turned this way and that, stretching up onto tip-toe, as he shouted and yelled. Another bluetit came to a lower branch and appeared to listen.

And this character (below) has dropped in every day for a week. He has a long spring-loaded tail which constantly twitches up and down as he hops and pecks about the pond and investigates the ground-feeder.

Grey Wagtail: Wikimedia: Glyn Baker Thrilled with so much success, I have plans for next year. I've invested in a silver birch and a holly for my 'wood.' And I'm creating a mini-orchard where my shed used to be. I have a cherry, a bardsey apple and a plum tree, all grown in pots. They have leaf-buds and seem to be doing well. I'm keenly looking forward to seeing how they do.

Grey Wagtail: Wikimedia: Glyn Baker Thrilled with so much success, I have plans for next year. I've invested in a silver birch and a holly for my 'wood.' And I'm creating a mini-orchard where my shed used to be. I have a cherry, a bardsey apple and a plum tree, all grown in pots. They have leaf-buds and seem to be doing well. I'm keenly looking forward to seeing how they do.They will add more leafage, more pollen-producing flowers (never mind the hay-fever) more bark - and therefore more insects. Which in turn will mean more birds and animals that eat insects. I would like to see frogs in my pond. And a newt. I would really love to have a newt.

I planted a St. Swithin rose today, to climb over a fence, both to hide the rather ugly fence and to provide more hiding/living space for birds and insects. I'd like to have a hazel tree in a pot because I love hazelnuts. And strawberries and bilberries. Perhaps a tiny wild flower meadow in a raised bed.

We shall see how much of this comes to - er - fruition.

Published on February 16, 2017 16:00

January 21, 2017

A Sterkarm Singalong

Tryst: (Old French) an appointed station in hunting. An appointed meeting place, often of lovers. To engage to meet a person or persons. A cattle market, e.g. 'The Falkirk Tryst.' A Sterkarm Tryst: an appointed meeting place of which only one side is aware: an ambush. Yesterday, January 24th, the third Sterkarm book,

A Sterkarm Tryst,

was published.

Tryst: (Old French) an appointed station in hunting. An appointed meeting place, often of lovers. To engage to meet a person or persons. A cattle market, e.g. 'The Falkirk Tryst.' A Sterkarm Tryst: an appointed meeting place of which only one side is aware: an ambush. Yesterday, January 24th, the third Sterkarm book,

A Sterkarm Tryst,

was published.It's the third in the series. The first two, after being out of print for some years, have been republished by Open Road. They are The Sterkarm Handshake and A Sterkarm Kiss.

The Sterkarm Handshake by Susan Price

The Sterkarm Handshake by Susan Price

A Sterkarm Kiss by Susan Price

A Sterkarm Kiss by Susan PriceThe stories were inspired by the reivers of the Scottish Borders though Handshake only came to life for me when I thought of sending 21st Century urbanites through a time machine to the 16th Century Border Country, where the Sterkarms take them for Elves. Their strange clothes and hairstyles give them an eldritch appearance and their carts which move without horses demonstrate their supernatural powers.

The Sterkarms, the local Riding or Raiding* Family, welcome the Elves at first, for their magical wee white pills (aspirin). The welcome doesn't last. The Border men were notoriously 'ill to tame' and the Sterkarms don't relish being told what they can and cannot do, even by Elves.

* 'Raid' is from the Scandinavian or Scottish form of the Old English 'rade', which meant 'road.' Our word 'road' is from the same Old English word, which also gave us 'ridan' or 'ride'. A road was where you rode. A track over a moor or through a wood is still called 'a ride.'

Raiding was often what you were doing when you rode down a road or ride. So a 'Riding Family' and a 'Raiding Family' were the same thing. Ride, road and raid all stem from the same word.

And 'reivers', as in Scottish Border reivers, comes from the same root as 'bereave,' which survives to the present almost exclusively in the sense of bereavement by death. 'To reave' originally meant to rob, to take, to forcibly deprive.Looking back over the books, I realise that the words and music of old ballads run through all of them. (I hear the music, anyway.) The 21st-Century heroine, Andrea, is 'embedded' (in more ways than one) with the 16th-Century Sterkarms and learns many songs from them. She finds that the songs often give her the words to understand the Sterkarms and her own situation.

I just thought you might like to know that.

The higher on the wing it climbsThe sweeter sings the lark,And the sweeter that a young man speaksThe falser is his heart.He'll kiss thee and embrace theeUntil he has thee won,Then he'll turn him round and leave theeAll for some other one.

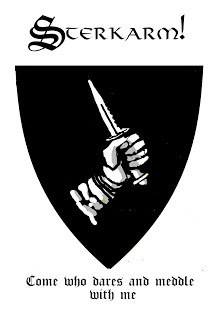

There's the ballad that gives the Sterkarms their rallying cry and boast:

My hob is swift-footed and sure,My sword hangs down at my knee, I never held back from a fight:Come who dares and meddle with me!

A 'hob' was the breed of small, strong, intelligent horse which the reivers rode (down roads on raids). This ballad was historically associated with the Elliot family rather than the Armstrong family on whom the Sterkarms are very, very loosely based. ('Sterkarm' means 'strong arm.)

These old songs fitted themselves naturally into the story as I wrote. I'd known many of them by heart for decades before I had any idea of writing the Sterkarm books. I never had to hunt for a quote. The scene I was working on would set a particular song playing in my head.

These old songs fitted themselves naturally into the story as I wrote. I'd known many of them by heart for decades before I had any idea of writing the Sterkarm books. I never had to hunt for a quote. The scene I was working on would set a particular song playing in my head.I knew the songs because, while still a young teenager, my love of folklore led me to Child's Ballads. I was already familiar with the lyrics before I discovered recordings of them by various folk-groups.

I was a deep-dyed folkie, me. I was having none of your long-haired sensitive types strumming acoustic guitars while they intoned modern protest songs. If it wasn't at least 200 years old, I didn't want to hear it. I wanted elbow-pipes, Shetland fiddles and bodhrans. I wanted people with closed eyes singing unaccompanied with one hand over an ear. "As I walked out one midsummer morning..."

It was the stories, of course, that attracted me. I wanted to hear about the Billy Blind starting up at the bed's foot and the loathly worm toddling about the tree.

I often listen to music while writing and, for me, the music has to be fitted to the book I'm working on. It creates the atmosphere. For the Sterkarms, it had to be the Border Ballads. The music and words of the ballads are, for me, as much a part of setting the Sterkarm scene as details of their food, clothing, furniture and buildings.

I wasn't too purist, though. In A Sterkarm Handshake, Per Sterkarm is wandering through the alleys of the tower, on his way to Andrea's 'bower' or bedchamber. He thinks he's on a promise.

Oh, pleasant thoughts come to my mindAs I turn back smooth sheets so fine,And her two white breasts are standing soLike sweet pink roses that bloom in snow.

The second book, A Sterkarm Kiss ends with the lines:

For there's sweeter restOn a true-love's breastThan any other where.

Neither of these quotes come from the Border ballads, although folk-song is, by its very nature, hard to date. The first verse, as far as I know, comes from 'The Factory Maid.'

I'm a hand-loom weaver by my trade,But I'm in love with a factory-maid,And could I but her favour win,I'd break my looms and weave with steam.

This dates it, probably, to the 19th century and means it's

Mayhew's broadside ballad sellerlikely to be a 'broadside ballad.' These were printed lyrics, often written about hot topics of the day, such as industrialisation, and sold in market-places. There was no music but the name of some well-known tune would be given. 'To be sung to the tune of...'

Mayhew's broadside ballad sellerlikely to be a 'broadside ballad.' These were printed lyrics, often written about hot topics of the day, such as industrialisation, and sold in market-places. There was no music but the name of some well-known tune would be given. 'To be sung to the tune of...' The lines about the true-love's breast come from a song with a lovely tune, which I know as 'Searching for Lambs.' (This being what 'the loveliest maid that e'er I saw' was doing when her lover walked out one midsummer morning.) It's very hard to guess at a date for the lovely maid and her ewes, but the song doesn't have the robust mix of the supernatural and extreme vengeful violence that typifies the Border ballads, so it's probably later.

This doesn't mean that the Sterkarms wouldn't know these verses. I justify my inclusion of them by the way that elements of folk-tales and ballads 'migrate,' turning up again and again in different songs and stories.

They were spread by word of mouth. If a singer or story-teller couldn't remember a detail, they invented their own. Or inserted a verse they could remember from another song. They might also take a verse from one song and put it into another simply because they liked it. Some old songs almost seem to be compilations of verses:

Oh had I wist, when first I kissedThat Love had been so ill to win,I'd have shut my heart in a silver cageAnd pinned it with a silver pin.

When cockle-shells turn silver bellsWhen fishes swim from tree to treeWhen ice and snow turn fire to burnIt's then, my love, that I'll love thee.

The men of the forest, they asked it of me,How many sweet strawberries grow in the salt sea;I answered them well, with a tear in my e'e;'As many fish swim in the forest.'

The writers of broadside ballads certainly drew on these old songs too, re-using verses to save time as they tried to make a living. So because a verse was published in a broadsheet ballad about a factory maid doesn't mean that something very like it wouldn't have been known earlier.

And just because a gentle love song doesn't mention treachery, incest, fratricide, infanticide or any of the other -cides so popular in the Border ballads, it doesn't mean it wasn't known on the Borders. Even there, they had their quieter moments.

I thought it was a pity that my readers couldn't hear the songs that are quoted so frequently throughout the Sterkarm books - and then realised that there was a way for me to share them. If you have a Facebook or Spotify account, here's a link to my playlist for the Sterkarm books. If you like songs about murder, revenge killings and executions - and the occasional love-song - this is for you.

Published on January 21, 2017 16:00

Singalong With The Sterkarms

A Sterkarm Tryst by Susan PriceTryst: (Old French) an appointed station in hunting. An appointed meeting place, often of lovers. To engage to meet a person or persons. A cattle market, e.g. 'The Falkirk Tryst.' A Sterkarm Tryst: an appointed meeting place of which only one side is aware: an ambush. On January 24th, the third Sterkarm book, A Sterkarm Tryst, will be published.

A Sterkarm Tryst by Susan PriceTryst: (Old French) an appointed station in hunting. An appointed meeting place, often of lovers. To engage to meet a person or persons. A cattle market, e.g. 'The Falkirk Tryst.' A Sterkarm Tryst: an appointed meeting place of which only one side is aware: an ambush. On January 24th, the third Sterkarm book, A Sterkarm Tryst, will be published.It's the third in the series. The first two, after being out of print for some years, have been republished by Open Road. They are The Sterkarm Handshake and A Sterkarm Kiss.

The Sterkarm Handshake by Susan Price

The Sterkarm Handshake by Susan Price

A Sterkarm Kiss by Susan Price

A Sterkarm Kiss by Susan Price(I've just been messaged on Facebook by a reader, who tells me she can now at last read Kiss, which she's been trying to find for ten years, and has pre-ordered Tryst. I can only say thank you for your stamina and thank you again.)

The books were inspired by the reivers of the Scottish Borders though Handshake only came to life for me when I thought of sending workers for a 21st Century company through a time machine to the 16th Century Border Country, where they hope to mine the coal, oil and gas. The 16th Century 'natives,' the Sterkarms, suppose them to be Elves. After all, the strange clothes of the 21st Century people give them an eldritch appearance and their carts which move without horses demonstrate their supernatural powers.

The Sterkarms, the local Riding or Raiding* Family, welcome the Elves at first, for their magical wee white pills which take away pain (aspirin). The welcome doesn't last. The Border men were notoriously 'ill to tame,' as a contemporary put it, and the Sterkarms don't relish being told what they can and cannot do, even by Elves.

*The word 'raid' is from the Scandinavian or Scottish form of the Old English 'rade', which meant 'road.' Our word 'road' is from the same Old English word, which also gave us 'ridan' or 'ride'. A road was where you rode. A track over a moor or through a wood is still called 'a ride.'

Raiding was often what you were doing when you rode down a road or ride. So a 'Riding Family' and a 'Raiding Family' were the same thing. Ride, road and raid all stem from the same word.

And 'reivers', as in Scottish Border reivers, comes from the same root as 'bereave,' which survives to the present almost exclusively in the sense of bereavement by death. 'To reave' originally meant to rob, to take, to forcibly deprive.Looking back over the books, I realise that the words and music of old ballads run through all of them. (I hear the music, anyway.) The 21st-Century heroine, Andrea, is 'embedded' (in more ways than one) with the 16th-Century Sterkarms and learns many songs from them. She finds that the songs often give her the words to understand the Sterkarms and her own situation.

I just thought you might like to know that.

The higher on the wing it climbsThe sweeter sings the lark,And the sweeter that a young man speaksThe falser is his heart.He'll kiss thee and embrace theeUntil he has thee won,Then he'll turn him round and leave theeAll for some other one.

Then there's the ballad which gives the Sterkarms their rallying cry and boast:

The 'Sterkarm Handshake': their badgeMy hob is swift-footed and sure,My sword hangs down at my knee, I never held back from a fight:Come who dares and meddle with me!

The 'Sterkarm Handshake': their badgeMy hob is swift-footed and sure,My sword hangs down at my knee, I never held back from a fight:Come who dares and meddle with me! A 'hob' was the breed of small, strong, intelligent horse which the reivers rode (down roads on raids). This ballad was historically associated with the Elliot family rather than the Armstrongs on whom the Sterkarms are very, very loosely based. ('Sterkarm' means 'strong arm.)

These old songs fitted themselves naturally into the story as I wrote. I'd known many of them by heart for decades before I had any idea of writing the Sterkarm books. I never had to hunt for a quote. The scene I was working on would set a particular song playing in my head.

I knew the songs because, while still a young teenager, my love of folklore led me to Child's Ballads. I was already familiar with the lyrics before I discovered recordings of them by various folk-groups and singers.

I was a deep-dyed folkie, me. I was having none of your long-haired sensitive types strumming acoustic guitars while they intoned modern protest songs. If it wasn't at least 200 years old, I didn't want to hear it. I wanted elbow-pipes, Shetland fiddles and bodhrans. I wanted people with closed eyes singing unaccompanied with one hand over an ear. "As I walked out one midsummer morning..."

It was the stories, of course, that attracted me. I wanted to hear about the Billy Blind starting up at the bed's foot and the loathly worm toddling about the tree. And the Broomfield Hill. And Twa Corbies.

I often listen to music while writing and, for me, the music has to be fitted to the book I'm working on. It creates the atmosphere. For the Sterkarms, it had to be traditional folk, especially the Border Ballads. The music and words of the ballads were as much a part of setting the Sterkarm scene as details of their food, clothing, furniture and buildings.

I wasn't too purist, though. In A Sterkarm Handshake, Per Sterkarm is hurrying through the alleys of the tower, on his way to Andrea's 'bower' (which just means 'bedroom' or 'sleeping place.) He thinks he's on a promise.

Oh, pleasant thoughts come to my mindAs I turn back smooth sheets so fine,And her two white breasts are standing soLike sweet pink roses that bloom in snow.

The second book, A Sterkarm Kiss ends with the lines:

For there's sweeter restOn a true-love's breastThan any other where.

Neither of these quotes come from the Border ballads, although folk-song is, by its very nature, hard to date or pin down to a specific place. The first verse, as far as I know, comes from 'The Factory Maid.'

I'm a hand-loom weaver by my trade,But I'm in love with a factory-maid,And could I but her favour win,I'd break my looms and weave with steam.

This dates it, roughly, to the late 18th or 19th century and means that this version is

Mayhew's broadside ballad sellerlikely to have been a 'broadside ballad.' These were lyrics, printed on the long sheets of paper which gave them their name. Often written about hot topics of the day, such as industrialisation, they were sold in market-places. There was no music but the name of some well-known tune would be given. 'To be sung to the tune of...'

Mayhew's broadside ballad sellerlikely to have been a 'broadside ballad.' These were lyrics, printed on the long sheets of paper which gave them their name. Often written about hot topics of the day, such as industrialisation, they were sold in market-places. There was no music but the name of some well-known tune would be given. 'To be sung to the tune of...' The lines about the true-love's breast come from a song with a beautiful tune, which I know as 'Searching for Lambs.' (This being what 'the loveliest maid that e'er I saw' was doing when her lover walked out one midsummer morning.) It's very hard to guess at a date for the lovely maid and her ewes, but the song doesn't have that robust mix of extreme vengeful violence and the supernatural that typifies the Border ballads, so it's probably later.

The date for my Sterkarms is about 1520 (though there were reivers long before and after this date.) Some of the songs I quote are certainly later and can be roughly dated to the late 1700s, but this doesn't mean that the Sterkarms wouldn't know something close to these lyrics and tunes. I justify my inclusion of them by the way that elements of folk-tales and ballads 'migrate,' from song to song and tale to tale over long periods of time.

The songs and stories were spread by word of mouth. If a singer or story-teller couldn't remember a detail, they invented their own. Or inserted a verse they could remember from another song. They might also take a verse from one song and put it into another simply because they liked it. They might change an ending to make it happier (see Johnny of Briedesley below) or change the relationships within a song, for example, having the hero murdered by his mother instead of his lover.

The same applies to the music. If they couldn't remember a tune, then they set the words to another or made up a variation. Other lyrics and tunes were updated. These tried-and-tested old tales can go on for centuries. Some researchers think some folk-tales go back to the Bronze Age.

Some old songs almost seem to be compilations of verses:

Oh had I wist, when first I kissedThat Love had been so ill to win,I'd have shut my heart in a silver cageAnd pinned it with a silver pin.

The men of the forest, they asked it of me,How many sweet strawberries grow in the salt sea?I answered them well, with a tear in my e'e;'As many fish swim in the forest.'

When cockle-shells turn silver bellsWhen fishes swim from tree to treeWhen ice and snow turn fire to burnIt's then, my love, that I'll love thee.

The writers of broadside ballads certainly drew on these old songs too, re-using verses to save time as they tried to make a living. So because a verse about a factory maid was published in a broadsheet ballad in, say 1810, it doesn't mean that something very like it wouldn't have been known very much earlier.

And just because a gentle love song doesn't mention treachery, incest, fratricide, infanticide or any of the other -cides so popular in the Border ballads, it doesn't mean it wasn't known on the Borders. Even there, they had their quieter moments.

I thought it a pity that my readers couldn't hear the songs that are quoted so frequently throughout the Sterkarm books - and then realised that there was a way for me to share them. If you have a Facebook or Spotify account, here's a link to my playlist for the Sterkarm books.

The songs here are the best versions I could find on Spotify of the ballads I quote, but they aren't definitive. For instance, in the linked Johnny of Breadiesley, sung by Ewan McColl, Johnny kills seven enemies and rides away triumphant. In other versions, he is killed: His good grey hounds are sleeping,/ his good grey hawk has flown,/ a grass green turf is at his head,/ and his hunting all is done. The verse quoted above, from January, [The higher on the wing it climbs...] also has slightly different words in the recording by June Tabor.

If you like songs about murder, revenge killings and executions - plus the occasional love-song - and if you like deep-dyed folk - this is for you.

Published on January 21, 2017 11:36

January 8, 2017

The Droving Trade

Highland Cattle: Attribution: © Francis C. Franklin / CC-BY-SA-3.0Can you imagine spending two months of every year walking 150 miles (242 kilometres) over challenging terrain, scrambling up steep, rocky hills, trudging miles across moors, fording rivers, lakes and even stretches of sea?

Highland Cattle: Attribution: © Francis C. Franklin / CC-BY-SA-3.0Can you imagine spending two months of every year walking 150 miles (242 kilometres) over challenging terrain, scrambling up steep, rocky hills, trudging miles across moors, fording rivers, lakes and even stretches of sea?For company, you’d have a large herd of long horned cattle: unpredictable, dangerous beasts. Most nights, you would sleep on the ground beside them. At journey’s end, having sold the cattle, you’d earn extra money by working at the local harvest before walking all the way home again. You would do this year after year, in hot sunshine, clouds of midges and pouring rain.

To us, with our comfortable, mostly indolent lives, this seems almost unbelievable, but it’s simply a description of the droving trade which went on for centuries. Highland regions, such as the Welsh and Scottish mountains, were best suited to pastoral farming, but to make a decent profit the beasts had to be brought to market in more prosperous regions, where higher prices were paid for meat.

No railways existed until the 1830s. There were no road vehicles capable of transporting large numbers of cattle, and no useable roads for such vehicles in any case. A huge amount of freight transport went by sea and river, but the task of transporting several hundred unhappy steers by small boats was expensive and difficult. And once landed, the cattle were still a long way from the best markets.

The simplest solution was to walk the beasts to market, step by step. Pigs, sheep and geese were also droved, with the geese fitted with sturdy boots for the journey by dipping their feet in tar.

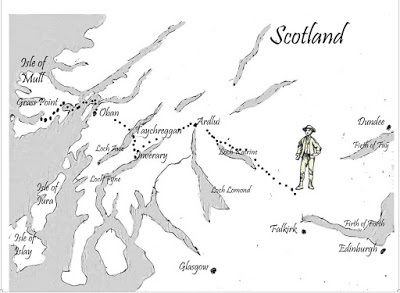

I researched the droving trade for my book, The Drover’s Dogs. My knowledge is slanted towards the Scottish trade, especially the journey from the Hebridean island of Mull in the west, to Lowland Scotland’s great ‘Tryst’ or cattle market in Falkirk in the east. (‘Tryst’ means ‘meeting place’ and, at the cattle trysts, sellers and buyers from all over Scotland met to do business.)

The drover's road from Mull to Falkirk, from The Drover's Dogs

The drover's road from Mull to Falkirk, from The Drover's Dogs A ‘drover’ could mean a herdsman who walked alongside the cattle with his dog and perhaps owned a couple of the driven beasts to a wealthy man whose main business was droving. Quite often, like Lachlan in my book, they were crofters themselves who would be driving their own beasts to market and earned extra income by adding some of their neighbour’s cattle to their drove.

The drover might buy his neighbours cattle outright, or he might simply promise to sell the cattle at the best price he could, and pass on the money to the crofter, minus an agreed cut.

In about May of each year, a drover would start enquiring among his neighbours: Who wanted to send beasts to market and how many? Roughly around June, the drovers began herding the cattle together in one place. A man might gather together a large herd, and had to remember who the owners of them all were, and what agreement he'd made with them. Later, he'd have to remember how much the beasts sold for. Some drovers could read and write. Many were illiterate and probably used tally-sticks to help them keep account. They also, undoubtedly, developed accurate and sharp memories.

Highlanders didn’t have a good reputation throughout most of the period and drovers were reputed to be lazy, drunken, dirty and stupid. They were called lazy because they often slept late at their ‘stances,’ the overnight camping places chosen for the water, shelter and grazing they provided. Drovers were seen sitting over their fires, eating breakfast and chatting until mid-morning. And even once started, they dawdled along.

Highlanders didn’t have a good reputation throughout most of the period and drovers were reputed to be lazy, drunken, dirty and stupid. They were called lazy because they often slept late at their ‘stances,’ the overnight camping places chosen for the water, shelter and grazing they provided. Drovers were seen sitting over their fires, eating breakfast and chatting until mid-morning. And even once started, they dawdled along.This wasn’t laziness. Hurried cattle lost weight and became less valuable. People who called the drovers ‘lazy’ had obviously never considered the hardness and danger of the drover’s life. To come from Mull, the cattle were first driven to Grass Point on Loch Spelve and loaded on to boats which carried them across the strait to the island of Kerrera. The cattle were unwilling. Drovers could be gored, trampled or crushed.

After disembarking on Kerrera, the cattle were driven the length of the island and then swum across the narrow stretch of sea to the mainland at Oban. Many men stripped off and swam with the cattle: another dangerous enterprise.

Once the mainland was gained, they walked the cattle up into hills and crossed Loch Awe and the sea loch, Loch Fyne. They were still only half-way. They had to skirt Loch Lomond, journey along the shores of Loch Katrine and even then there were miles to walk before they reached Falkirk. This is a lot easier to write down and read than it was to do it in 1800 or earlier!

In earlier centuries, the cattle might have to be defended against robbers, though this was less likely in 1800, when my story is set. The drovers’ diet for this arduous journey was mostly oats, onions and whisky. I imagine they made what later became known as 'Waterloo porridge' because the soldiers before Waterloo were forbidden a fire to make a hot meal. Dry oats were mixed into cold water. The onions were probably eaten as we would eat an apple. For a little more protein, they might open one of the bullock’s neck veins and mix the blood into their porridge

So the accusation of laziness doesn’t stand, but drovers were certainly dirty, at least while droving, since they slept rough or in the notoriously unsavoury inns of the Highlands. There was probably also some substance to the accusation of drunkenness. If I had to live like that, I would make the most of the whisky too.

But stupid? Many reasons probably underlay this insult. The drovers were usually considered illiterate, uneducated farm-hands. They were also Highlanders too, and Highlanders, in 1715 and 1745 had risen in rebellion against the English state. The last Jacobite uprising had taken place a mere 55 years before my story is set: within living memory.

The Highlanders first language was Gaelic and they were mostly Catholic, so they were divided by language, culture and religion from the English and from Lowland Scots who, at best, considered Highlanders to be ‘noble savages.’ At worst, they thought them

a lower form of life: stupid, dishonest and dangerous.

But a successful drover needed a sharp intelligence. Success depended on bringing the cattle to market in good condition and perhaps even better fed on grazing along the way than they had started. To manage this, a drover needed not only expert knowledge of cattle but a weather eye and close acquaintance with every stance along the way. Would the tracks ahead be muddy and impassable: was it worth taking another way? Was it worth hurrying the cattle a little to reach the next stance before another drove who might leave nothing to graze?

He had to be able to manage men, and have a phenomenal memory for places, people and the deals he’d made. Even if illiterate, he likely had great quickness with numbers. I'm reminded of an Italian

woman I once knew who was illiterate in both English and Italian, but to assume from this that she was stupid would have been a big mistake. She understood numbers, prices and weights very well, adding up, subtracting and dividing long lists of numbers with a speed and accuracy that made me dizzy. Lord help anyone who tried to short-change her. I imagine that, from long practice, the drovers had the same facility. In short, to be sure of finding a fool at a drovers' stance, you had to take one with you.

Drovers were also honest, or as honest as any trader can be. Most business at the time was conducted on a handshake and a dishonest man would soon have had no business at all. Again, I offer a modern parallel. I have family connections with a small island where a great deal of business is still conducted on trust because nearly all families are interconnected and everyone knows, or knows of, everyone else.

Any incoming clever-clogs who try to take advantage of this trusting ‘naivety’ soon find that no locals will do any business with them at all. No credit is to be had. If they need an electrician, decorator, plumber etc, it's impossible to find one who isn't solidly booked up. Word has gone round. I imagine that any drover who tried to cheat the crofters would soon have found himself with no trade and no friends.

Although probably as old as agriculture, the droving trade prospered with the rise of urban living. Demand for meat grew with the population and wealth of towns. Prices rose in those markets that supplied urban areas and it was more profitable to undertake the arduous droves to those markets than sell or barter your cattle more locally. The real hey-day came in the 18th and early 19th Centuries. Towns continued to grow and wars in Europe meant a steep rise in demand for beef from the Army and Navy.

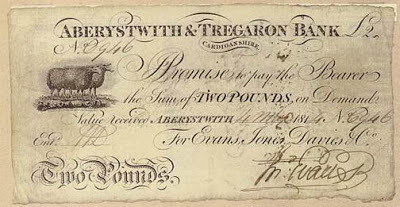

A Welsh bank noteThe increase in droving stimulated the development of banking. Returning drovers often carried large, heavy sums of cash across lonely moors and mountains. So banks set up near the Trysts. The drover could place his cash in their strongboxes and receive in return a paper ‘note’ which was lighter to carry and less temptation to robbers. On reaching the end of his journey, he took this note to another branch of the bank and ‘cashed it.’ Payment was sometimes accepted in these signed and co-signed notes, fore-runners of paper money.

A Welsh bank noteThe increase in droving stimulated the development of banking. Returning drovers often carried large, heavy sums of cash across lonely moors and mountains. So banks set up near the Trysts. The drover could place his cash in their strongboxes and receive in return a paper ‘note’ which was lighter to carry and less temptation to robbers. On reaching the end of his journey, he took this note to another branch of the bank and ‘cashed it.’ Payment was sometimes accepted in these signed and co-signed notes, fore-runners of paper money.Many of these banks, such as Llandovery’s Black Ox Bank, took an ox or bull as their symbol, in honour of their connection with the droving trade. The Welsh one, above, has a drawing of sheep.

The end of the droving trade was brought about mainly by two things: peace and steam.

The Drover's Dogs by Susan PriceThe end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, meant a great fall in the demand for beef. At the same time, agricultural improvements meant that greater numbers of cattle were kept alive over winter and larger, fatter cattle were bred, in greater numbers, close to towns where demand was greatest.

The Drover's Dogs by Susan PriceThe end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, meant a great fall in the demand for beef. At the same time, agricultural improvements meant that greater numbers of cattle were kept alive over winter and larger, fatter cattle were bred, in greater numbers, close to towns where demand was greatest.And then came steam which ‘carried away the droving trade.’ By the 1840s, railways had spread throughout west Scotland (and the rest of Britain.) Tracks could extend to depots almost at the dock-sides. Cattle could be shipped in the large holds of sturdy, iron steam-ships and then loaded into cattle trucks which were dragged away by steam-train. Drovers arrived at market to find that all demand had been satisfied by cattle who’d arrived more speedily by train.

The Sterkarm Handshake

The Sterkarm HandshakeThe ancient droving trade had been a hard one, but it had been one way a highland crofter could earn hard cash to pay his rent. Its end pushed many crofters into hardship and emigration.

Susan Price is the Carnegie medal winning author of The Ghost Drum and The Sterkarm Handshake.

The Drover’s Dogs is her first entirely original self-published book.

Published on January 08, 2017 11:27

December 24, 2016

Ghosts of Christmas Past

My mother loved Christmas.

You know who he is - illustrated by T Nast (Public Domain Review)

You know who he is - illustrated by T Nast (Public Domain Review)

She was born in 1929, the youngest of six children. Every year, at Christmas, she told us about Christmas when she'd been a child.

The Christmas, for instance when, coming down in the morning, she found a monkey in the kitchen. One of her three older brothers had somehow acquired it at the Christmas Wake (a fair.) Christmas spirit had probably been strong in the brother, if not the monkey. What happened to the monkey? As with many of my mother's stories, I don't know. I can't remember her ever telling me that. Perhaps she didn't know herself. I can't imagine the monkey remaining a member of the household for very long after my grandmother arrived home.

Every Christmas without fail, we heard about the big white enamelled bucket. It had a lid. It was a lidded big white enamel bucket.

For most of the year the big white enamelled bucket with a lid was for fetching water from the pump in the yard and storing it in the house. But at Christmas, it was used for storing nuts instead. What was done with the water over Christmas? Were people pushed out into the freezing slippery yard with jugs and basins? Again, I was never told. But at Christmas, for sure, that big white enamelled bucket with the lid was filled to overflowing with monkey-nuts, walnuts, cobnuts and brazils, all of them still in their shells. The nutcrackers lay on the top, nestling into the nuts, ready for use. I think it was the great quantity of that luxury, nuts, that had impressed my mother.

Walnuts were, by the way, fun for all the family. Carefully shell two walnuts so you have four perfect half-shells. Scrape them out and make them smooth. Scoop up a passing cat. (There were always a few cats about in my mother's house. There was one which my mother strongly resented because it could open the back door when she was still too short to reach the latch. On returning from school to an empty house, she used to have to wait in the yard until the cat chose to saunter home and let her in. Despite this, she was a great cat-lover in later life.)

Anyroad, the cat and the walnut shells. Fit a half-shell onto each of its paws, then put the cat down on the bare stone flags or tiles. There were no carpets in my mother's home. The cat finds itself tap-dancing. Never having heard a sound from its own feet before, it attempts to escape the clatter, only to tap louder. The more frantically the cat tries to escape the noise, the louder the clatter of walnut shells on stone becomes.

This was more fun for my mother's brothers, admittedly, than for the cat. But they had to make their own entertainment in those days.

Another use for walnut shells. Mum taught us how to make little boats out of the half-shells. Fitted with matchstick masts and paper sails, they formed a flotilla in a bowl of water.

And corks. Most bottles in her childhood had real corks, and more corks were pulled at Christmas than at any other time. These were turned into horses, to stand about on the bowl's shore, admiring the boats. The horses' legs were matchsticks, and a head and neck were cut out of card. A slit in the end of the cork allowed the cardboard head to be slotted into place. Tails and manes could be made from bits of old wool. You could blacken the end of the matchsticks to make hooves and draw in eyes and mouths. You could even make them saddles and reins.

Walnuts, wikimedia

Walnuts, wikimedia

My mother, as the youngest of six, considered herself spoiled but Christmas in the 1930s was still for most people, as it had been for centuries, a brief time of treats in a year of penny-pinching and making-do. Another of my mother's memories was of how an apple was a thing to be cherished and hoarded for days. She polished it on her sleeve, sniffed it, imagined how it would taste. She showed it off and would have all the other children in the street following her about and trying to become her bestest friend, in the hope that, when she finally ate the apple, they might be allowed to have the core.

At Christmas she looked forward to having a rare tangerine in the toe of her stocking - and this was one of her old socks, not a novelty gift-bag. The stocking would hold a sugar mouse too, and some nuts and raisins.

tangerine: Wikimedia My grandmother spread the cost of Christmas over many weeks. After all, she had six sugar mice and six tangerines to buy. She bought white mice for the boys and pink ones for the girls from their corner shop (which was a house with its front room turned into a shop.)

tangerine: Wikimedia My grandmother spread the cost of Christmas over many weeks. After all, she had six sugar mice and six tangerines to buy. She bought white mice for the boys and pink ones for the girls from their corner shop (which was a house with its front room turned into a shop.)

My mother told me of the ingenious way that my grandmother and other women stretched their money. Twenty of them met, every week, in the local pub. The landlady of the pub, who they obviously trusted, acted as treasurer. Each woman put a shilling (5p) into a big jar. For the first week, nothing was paid out, but a time-table was drawn up for twenty weeks ahead. Each woman drew one of these weeks out of a hat.

The next week, they again put in a shilling, so the jar held 40 shillings or two pounds. The woman who had drawn the first week was given twenty shillings, or one pound, from the jar.

The next week, they all put in another shilling and the woman who'd drawn the second week was given a pound - and so on. This 'Inflation Calculator' reckons that £1 in 1935 would have been worth about £50 today, whereas the shilling each woman put in was worth about £2-50.

This ingenious system allowed the women to budget ahead. This week and next week, they were hard-up - ah, but the week after that they would have a whole pound to play with. They could delay large purchases, like coal, until 'their week.' They also made arrangements between each other. If one woman desperately needed the money that week and another could wait, they swopped weeks. When it was their week to receive a pound, they often asked to be given only 19/- (the /- meant 'shilling') and so covered their payment into the pool.

But I was telling you about sugar mice. After Christmas, my mother said, she and the brothers nearest her in age hid their stocking and sugar-mouse from the others. The utmost ingenuity and enterprise had to be used because if one of them found the stockings belonging to the others, they would eat sugar-mouse, raisins, nuts and all while hoping that the others hadn't found their special, secret, undetectable hiding-place. The two oldest sisters never bothered to hide their stockings. Since their mother worked, these two acted as mothers to the rest and it was considered bad form to gnaw their mice when they hadn't even hidden them. (The oldest brother's stocking was also safe. He worked in a steel-mill, flinging and catching bolts of white-hot iron with a pair of long tongs. Nobody was going to nick his sugar-mouse.)

My mother was usually given a 'Wonder Book' for Christmas too: a large, hard-backed book, full of stories, puzzles, things to make, and experiments to try. They were often beautifully illustrated. My mother loved and treasured hers but one day, when she was twelve, returned home from school to find that her mother had given all of them away, together with many of her toys because 'she was too old for things like that now.'

My mother was usually given a 'Wonder Book' for Christmas too: a large, hard-backed book, full of stories, puzzles, things to make, and experiments to try. They were often beautifully illustrated. My mother loved and treasured hers but one day, when she was twelve, returned home from school to find that her mother had given all of them away, together with many of her toys because 'she was too old for things like that now.'

This was one reason why my mother bought us so many books, including second-hand copies of her old wonder-books, and why she would never, never even consider throwing or giving away anything that belonged to us without our permission. I don't think she ever forgave my grandmother for giving away her things. (To speak in my grandmother's defense: She had herself started work at 10, so perhaps 12 did seem 'too old' for toys to her. Also, she never understood why anyone would waste their time reading. She spent Christmas at our house once, in her old age and stared for a long time at the floor-to-ceiling books before shaking her head and saying, "But what use am they?" We were without answer. To us, it was like asking what use the floor or walls were.)

My mother copied her mother in this much: she started buying for Christmas in August. Gifts would be stashed away in the bottom of her wardrobe or on top of it. Bottles of booze and ingredients for baking would be packed onto the back pantry shelf. The chest at the bottom of the hall would be slowly filled with nets of nuts, bags of crisps, packets of biscuits and sweets. She never allowed for the fact that she had only three children (four when my youngest brother arrived) and not six. We would be eating 'Christmas treats' until Easter.

In the week running up to Christmas, she would organise us as hands for her mincepie factory. She would make the pastry. One of us would grease tins. Another would cut out pastry circles. A third would fill the pies. The one who'd been greasing tins would then go to the other end of the line and stick on lids. Milk and egg was brushed on. Sugar was sprinkled. Mother operated the oven, putting tray after tray in, and bringing out sweet, spicy mincepies in batches of twelve.

Nightcomers by Susan PriceWe always had a Christmas tree and Mom would tell us how, when she'd been a child, they had a 'bush' not a tree. This was a construction of coat-hangers or wooden rods, fastened together to make a cross. It was covered with greenery or tinsel and hung from the ceiling. Glass ornaments, holly or mistletoe could be added, according to taste.

Nightcomers by Susan PriceWe always had a Christmas tree and Mom would tell us how, when she'd been a child, they had a 'bush' not a tree. This was a construction of coat-hangers or wooden rods, fastened together to make a cross. It was covered with greenery or tinsel and hung from the ceiling. Glass ornaments, holly or mistletoe could be added, according to taste.

Many of the ornaments we hung on our tree had a long history and stories attached. In the 'trimmings-box' we had some bits of blackened string with odd little wormy bits dangling from them. My mother told us that this had once been tinsel. When new it had been as bright and shiny as the glittering tinsel we enjoyed, but it had tarnished and turned black. We still hung it on our tree, in memory of Christmases past.

My mother's memories of Christmas and my own inspired my story 'The Christmas Trees' which, if you're still in the mood for Christmas, you can read here.

It's the gentlest and most nostalgic story in my collection, Nightcomers: Eight Stories of the Uncanny.

You know who he is - illustrated by T Nast (Public Domain Review)

You know who he is - illustrated by T Nast (Public Domain Review)She was born in 1929, the youngest of six children. Every year, at Christmas, she told us about Christmas when she'd been a child.

The Christmas, for instance when, coming down in the morning, she found a monkey in the kitchen. One of her three older brothers had somehow acquired it at the Christmas Wake (a fair.) Christmas spirit had probably been strong in the brother, if not the monkey. What happened to the monkey? As with many of my mother's stories, I don't know. I can't remember her ever telling me that. Perhaps she didn't know herself. I can't imagine the monkey remaining a member of the household for very long after my grandmother arrived home.

Every Christmas without fail, we heard about the big white enamelled bucket. It had a lid. It was a lidded big white enamel bucket.

For most of the year the big white enamelled bucket with a lid was for fetching water from the pump in the yard and storing it in the house. But at Christmas, it was used for storing nuts instead. What was done with the water over Christmas? Were people pushed out into the freezing slippery yard with jugs and basins? Again, I was never told. But at Christmas, for sure, that big white enamelled bucket with the lid was filled to overflowing with monkey-nuts, walnuts, cobnuts and brazils, all of them still in their shells. The nutcrackers lay on the top, nestling into the nuts, ready for use. I think it was the great quantity of that luxury, nuts, that had impressed my mother.

Walnuts were, by the way, fun for all the family. Carefully shell two walnuts so you have four perfect half-shells. Scrape them out and make them smooth. Scoop up a passing cat. (There were always a few cats about in my mother's house. There was one which my mother strongly resented because it could open the back door when she was still too short to reach the latch. On returning from school to an empty house, she used to have to wait in the yard until the cat chose to saunter home and let her in. Despite this, she was a great cat-lover in later life.)

Anyroad, the cat and the walnut shells. Fit a half-shell onto each of its paws, then put the cat down on the bare stone flags or tiles. There were no carpets in my mother's home. The cat finds itself tap-dancing. Never having heard a sound from its own feet before, it attempts to escape the clatter, only to tap louder. The more frantically the cat tries to escape the noise, the louder the clatter of walnut shells on stone becomes.

This was more fun for my mother's brothers, admittedly, than for the cat. But they had to make their own entertainment in those days.

Another use for walnut shells. Mum taught us how to make little boats out of the half-shells. Fitted with matchstick masts and paper sails, they formed a flotilla in a bowl of water.

And corks. Most bottles in her childhood had real corks, and more corks were pulled at Christmas than at any other time. These were turned into horses, to stand about on the bowl's shore, admiring the boats. The horses' legs were matchsticks, and a head and neck were cut out of card. A slit in the end of the cork allowed the cardboard head to be slotted into place. Tails and manes could be made from bits of old wool. You could blacken the end of the matchsticks to make hooves and draw in eyes and mouths. You could even make them saddles and reins.

Walnuts, wikimedia

Walnuts, wikimediaMy mother, as the youngest of six, considered herself spoiled but Christmas in the 1930s was still for most people, as it had been for centuries, a brief time of treats in a year of penny-pinching and making-do. Another of my mother's memories was of how an apple was a thing to be cherished and hoarded for days. She polished it on her sleeve, sniffed it, imagined how it would taste. She showed it off and would have all the other children in the street following her about and trying to become her bestest friend, in the hope that, when she finally ate the apple, they might be allowed to have the core.

At Christmas she looked forward to having a rare tangerine in the toe of her stocking - and this was one of her old socks, not a novelty gift-bag. The stocking would hold a sugar mouse too, and some nuts and raisins.

tangerine: Wikimedia My grandmother spread the cost of Christmas over many weeks. After all, she had six sugar mice and six tangerines to buy. She bought white mice for the boys and pink ones for the girls from their corner shop (which was a house with its front room turned into a shop.)

tangerine: Wikimedia My grandmother spread the cost of Christmas over many weeks. After all, she had six sugar mice and six tangerines to buy. She bought white mice for the boys and pink ones for the girls from their corner shop (which was a house with its front room turned into a shop.)My mother told me of the ingenious way that my grandmother and other women stretched their money. Twenty of them met, every week, in the local pub. The landlady of the pub, who they obviously trusted, acted as treasurer. Each woman put a shilling (5p) into a big jar. For the first week, nothing was paid out, but a time-table was drawn up for twenty weeks ahead. Each woman drew one of these weeks out of a hat.

The next week, they again put in a shilling, so the jar held 40 shillings or two pounds. The woman who had drawn the first week was given twenty shillings, or one pound, from the jar.

The next week, they all put in another shilling and the woman who'd drawn the second week was given a pound - and so on. This 'Inflation Calculator' reckons that £1 in 1935 would have been worth about £50 today, whereas the shilling each woman put in was worth about £2-50.

This ingenious system allowed the women to budget ahead. This week and next week, they were hard-up - ah, but the week after that they would have a whole pound to play with. They could delay large purchases, like coal, until 'their week.' They also made arrangements between each other. If one woman desperately needed the money that week and another could wait, they swopped weeks. When it was their week to receive a pound, they often asked to be given only 19/- (the /- meant 'shilling') and so covered their payment into the pool.

But I was telling you about sugar mice. After Christmas, my mother said, she and the brothers nearest her in age hid their stocking and sugar-mouse from the others. The utmost ingenuity and enterprise had to be used because if one of them found the stockings belonging to the others, they would eat sugar-mouse, raisins, nuts and all while hoping that the others hadn't found their special, secret, undetectable hiding-place. The two oldest sisters never bothered to hide their stockings. Since their mother worked, these two acted as mothers to the rest and it was considered bad form to gnaw their mice when they hadn't even hidden them. (The oldest brother's stocking was also safe. He worked in a steel-mill, flinging and catching bolts of white-hot iron with a pair of long tongs. Nobody was going to nick his sugar-mouse.)

My mother was usually given a 'Wonder Book' for Christmas too: a large, hard-backed book, full of stories, puzzles, things to make, and experiments to try. They were often beautifully illustrated. My mother loved and treasured hers but one day, when she was twelve, returned home from school to find that her mother had given all of them away, together with many of her toys because 'she was too old for things like that now.'

My mother was usually given a 'Wonder Book' for Christmas too: a large, hard-backed book, full of stories, puzzles, things to make, and experiments to try. They were often beautifully illustrated. My mother loved and treasured hers but one day, when she was twelve, returned home from school to find that her mother had given all of them away, together with many of her toys because 'she was too old for things like that now.'This was one reason why my mother bought us so many books, including second-hand copies of her old wonder-books, and why she would never, never even consider throwing or giving away anything that belonged to us without our permission. I don't think she ever forgave my grandmother for giving away her things. (To speak in my grandmother's defense: She had herself started work at 10, so perhaps 12 did seem 'too old' for toys to her. Also, she never understood why anyone would waste their time reading. She spent Christmas at our house once, in her old age and stared for a long time at the floor-to-ceiling books before shaking her head and saying, "But what use am they?" We were without answer. To us, it was like asking what use the floor or walls were.)

My mother copied her mother in this much: she started buying for Christmas in August. Gifts would be stashed away in the bottom of her wardrobe or on top of it. Bottles of booze and ingredients for baking would be packed onto the back pantry shelf. The chest at the bottom of the hall would be slowly filled with nets of nuts, bags of crisps, packets of biscuits and sweets. She never allowed for the fact that she had only three children (four when my youngest brother arrived) and not six. We would be eating 'Christmas treats' until Easter.

In the week running up to Christmas, she would organise us as hands for her mincepie factory. She would make the pastry. One of us would grease tins. Another would cut out pastry circles. A third would fill the pies. The one who'd been greasing tins would then go to the other end of the line and stick on lids. Milk and egg was brushed on. Sugar was sprinkled. Mother operated the oven, putting tray after tray in, and bringing out sweet, spicy mincepies in batches of twelve.

Nightcomers by Susan PriceWe always had a Christmas tree and Mom would tell us how, when she'd been a child, they had a 'bush' not a tree. This was a construction of coat-hangers or wooden rods, fastened together to make a cross. It was covered with greenery or tinsel and hung from the ceiling. Glass ornaments, holly or mistletoe could be added, according to taste.

Nightcomers by Susan PriceWe always had a Christmas tree and Mom would tell us how, when she'd been a child, they had a 'bush' not a tree. This was a construction of coat-hangers or wooden rods, fastened together to make a cross. It was covered with greenery or tinsel and hung from the ceiling. Glass ornaments, holly or mistletoe could be added, according to taste.Many of the ornaments we hung on our tree had a long history and stories attached. In the 'trimmings-box' we had some bits of blackened string with odd little wormy bits dangling from them. My mother told us that this had once been tinsel. When new it had been as bright and shiny as the glittering tinsel we enjoyed, but it had tarnished and turned black. We still hung it on our tree, in memory of Christmases past.

My mother's memories of Christmas and my own inspired my story 'The Christmas Trees' which, if you're still in the mood for Christmas, you can read here.

It's the gentlest and most nostalgic story in my collection, Nightcomers: Eight Stories of the Uncanny.

Published on December 24, 2016 16:00

December 2, 2016

Gain Inner Peace by Filing Your Tax Return

It's so easy to file your taxes on-line!

Found inner peace? Not.Go paperless. Submit your tax return on-line.Gain inner peace by filing your taxes on-line.

Found inner peace? Not.Go paperless. Submit your tax return on-line.Gain inner peace by filing your taxes on-line.

I've just wasted about three days of my life trying to gain this inner peace. My rug is badly chewed. I have carpet fibres in my teeth and bald patches on my head.

Like so much government double-speak - like, 'We're in this together' and 'The NHS is safe in our hands' - they know very well that not a word, not a syllable, not a letter of it is true, but still, they stoutly maintain these falsehoods in the face of our boos and hisses.

I first logged on to complete my return a couple of months ago. I found that it had been partly filled in for me by some HMI gremlin. The gremlin stated that I had been paid a sum of money as an employee. Because I had been paid this sum, I owed Pay-As-You-Earn tax.

This was completely wrong. I haven't been employed by another party for about 40 years. Even when I was a Royal Literary Fund Fellow, even when I go into schools to give talks and workshops, I retain my self-employed status, as do most writers.

The money that HMI had its underpants twisted about had nothing to do with employment. It came from a matured investment.

The money that HMI had its underpants twisted about had nothing to do with employment. It came from a matured investment.

Long, long ago, O Best Beloveds, back in the stone-age, it was not possible for a self-employed person to have a personal pension. So, thinking that I should salt away a few quid for my old age, I opened a 'Retirement Account' into which I intended to stuff what little surplus moolah came my way.

Almost immediately after I opened it, the law changed and I was able to set up a personal pension, which seemed the better option. I couldn't take the money from the Retirement Account: it was in there for the long term. So I just left it. I added no more to it.

Then old age came upon me and I was notified that the account had matured. The matured pot was hardly life-altering. It wouldn't have bought a Tory MP a pedigree duck, let alone build a duck house. So I took it as cash. It was this money that HMI were claiming was payment for employment that I owed PAYE on.

Baphomet. Contact Him @widdershins...I attempted to correct the on-line form. This only resulted in a lot of red splatter and big error messages. It wouldn't allow me to go forward to the next page until I had corrected the 'errors.'

Baphomet. Contact Him @widdershins...I attempted to correct the on-line form. This only resulted in a lot of red splatter and big error messages. It wouldn't allow me to go forward to the next page until I had corrected the 'errors.'

So I wrote to the Taxman, asking what I should do. I suggested they send me a paper tax form which wouldn't answer back when I filled it in.

I wrote to them because my experience of trying to contact tax people by phone is dismal. It's much easier to contact Baphomet. With the taxman, even if you have a cup of coffee and a book and hang on the phone for hours, when you finally get through, you are immediately cut off. Deliberately, I suspect. Now, I have relatives that work in tax-offices and so I've heard something of the pressure tax-office workers are under and I don't blame them. Much.

Months passed. And finally, I got a letter from HMI. It said I was now too late to return a paper tax-form without being fined. Phone the number on the letter, it said, to be talked through the problem.

So I phoned, luckily without high expectations, and explained. A bored young woman said, "Oh, just ignore it and when you get to any other comments, put an explanation in there. When we check the form, we'll see it."

I went back to the on-line form. Whenever you sign in now, you get a phone-call from a rather abrupt robotic female who dictates a number to you. To some numbers she gives a Russian accent, while others she speaks as a South African. Occasionally she sounds a bit American. It's often quite hard to tell what numbers she's saying because, just as you've got used to one barely comprehensible accent, she springs another on you. And then snaps, "Goodbye."

I went through this rigmarole with her several times because as soon as I got into the HMI site, it crashed, putting up a message 'We are having problems. Try again later.' This happened at least three times.

When I finally managed to log on, all those big red letters and error messages about owing money on PAYE had vanished. The gremlins had been in again, tidying up.

Still, I thought I ought to mention it in 'any other comments' just to make sure the mistake was understood. I wrote in a few words, but wasn't allowed to submit them. Red error messages again. And then the whole site crashed.

Another conversation with the woman with the strangely shifting accent. Another crash. And so the long winter evenings wore on. How glad I am to have HMI and their number-fixated friend to pass the time with. I've nothing better to do after all.

With perseverence, I got back on the site - and somehow, everything was okay, my message was suddenly acceptable and I'm allowed to submit. My tax return is, finally, done.

If this terrible site, with its glitches and crashes, had delayed me until January 31st, I'm sure HMI would have gleefully fined me. Or is that the reason why the site is so bad? To give an excuse to fine people?

Filing on-line is easy? It provides inner peace? Whoever came up with those slogans, they owe me a new rug and I would like to eat their young. Baphomet has some great recipes.

Found inner peace? Not.Go paperless. Submit your tax return on-line.Gain inner peace by filing your taxes on-line.

Found inner peace? Not.Go paperless. Submit your tax return on-line.Gain inner peace by filing your taxes on-line.I've just wasted about three days of my life trying to gain this inner peace. My rug is badly chewed. I have carpet fibres in my teeth and bald patches on my head.

Like so much government double-speak - like, 'We're in this together' and 'The NHS is safe in our hands' - they know very well that not a word, not a syllable, not a letter of it is true, but still, they stoutly maintain these falsehoods in the face of our boos and hisses.

I first logged on to complete my return a couple of months ago. I found that it had been partly filled in for me by some HMI gremlin. The gremlin stated that I had been paid a sum of money as an employee. Because I had been paid this sum, I owed Pay-As-You-Earn tax.

This was completely wrong. I haven't been employed by another party for about 40 years. Even when I was a Royal Literary Fund Fellow, even when I go into schools to give talks and workshops, I retain my self-employed status, as do most writers.

The money that HMI had its underpants twisted about had nothing to do with employment. It came from a matured investment.

The money that HMI had its underpants twisted about had nothing to do with employment. It came from a matured investment.Long, long ago, O Best Beloveds, back in the stone-age, it was not possible for a self-employed person to have a personal pension. So, thinking that I should salt away a few quid for my old age, I opened a 'Retirement Account' into which I intended to stuff what little surplus moolah came my way.

Almost immediately after I opened it, the law changed and I was able to set up a personal pension, which seemed the better option. I couldn't take the money from the Retirement Account: it was in there for the long term. So I just left it. I added no more to it.

Then old age came upon me and I was notified that the account had matured. The matured pot was hardly life-altering. It wouldn't have bought a Tory MP a pedigree duck, let alone build a duck house. So I took it as cash. It was this money that HMI were claiming was payment for employment that I owed PAYE on.

Baphomet. Contact Him @widdershins...I attempted to correct the on-line form. This only resulted in a lot of red splatter and big error messages. It wouldn't allow me to go forward to the next page until I had corrected the 'errors.'

Baphomet. Contact Him @widdershins...I attempted to correct the on-line form. This only resulted in a lot of red splatter and big error messages. It wouldn't allow me to go forward to the next page until I had corrected the 'errors.'So I wrote to the Taxman, asking what I should do. I suggested they send me a paper tax form which wouldn't answer back when I filled it in.