Susan Price's Blog: Susan Price's Nennius Blog, page 16

January 11, 2013

The Little Bad Wolf and the Big Chocolate Cake

David Rose Last week I was talking about the importance of story-telling to literacy.

David Rose Last week I was talking about the importance of story-telling to literacy. But more formal lessons are important too. This link will take you to David Rose’s site,where he explains some of the techniques he’s used, in Australia, to ‘accelerate learning’ across all backgrounds and ages.

First, the teacher prepares a text.

This means choosing a text which interests and engages the students and reading it with them. Terms new to the students are explained, and any background or context needed is also supplied. For instance, a wolf may be big and bad, but what is a wolf anyway? Students may never have heard of one before. (My aunt taught Black Country children of primary age who didn’t know what a cow was. They knew only one word for any kind of four-legged animal: ‘dog.’ I wish I could believe this would be impossible now, but I fear it's not.)

Not a dog. Pig fancier. After preparing the text comes a detailed reading of it. The teacher gives students a lot of help in identifying words and groups of words.

Not a dog. Pig fancier. After preparing the text comes a detailed reading of it. The teacher gives students a lot of help in identifying words and groups of words.For instance, say the class are studying the story of the three little pigs. The teacher might say: 'Let's look at the title first. That's this line at the top. It tells you what the story's about. It says, 'The Three Little Pigs.' Who can find the word 'pigs'?

"Yes! That's right. It's the word at the end. Let's highlight it.

"What kind of pigs are they?

"Right! Excellent! They are little pigs. Can we find the word that says 'little?' Great! - let's highlight that one too.'

And so on. Lots of looking at the text, lots of praise, lots of repetition of a fairly simple task. But the repetition is driving the lesson home. If you repeatedly search for and look at something, you are going to remember it. The students are being 'laddered' to improved reading. You don't leap from the ground to the roof of your house in one mighty bound - but you can climb up there, one rung at a time, on a ladder. And you're more likely to keep climbing if, at every step, you're given reason to feel pleased with yourself.

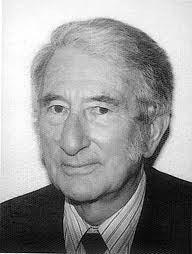

The late Michel Thomas This has a lot in common with Michel Thomas' method of teaching language. Thomas insisted that the student should be completely relaxed and stress-free. They should not attempt to remember what they were being taught, or do homework. It was the teacher's responsibility, Thomas said, to structure the lessons in such a way that the student learned. Any kind of stress or anxiety, he believed, makes learning harder. Haven't we all experienced that? I know that I can type fast and accurately if I'm alone, but if someone's watching me, I might as well be typing in mittens

The late Michel Thomas This has a lot in common with Michel Thomas' method of teaching language. Thomas insisted that the student should be completely relaxed and stress-free. They should not attempt to remember what they were being taught, or do homework. It was the teacher's responsibility, Thomas said, to structure the lessons in such a way that the student learned. Any kind of stress or anxiety, he believed, makes learning harder. Haven't we all experienced that? I know that I can type fast and accurately if I'm alone, but if someone's watching me, I might as well be typing in mittens Above, I've used 'Three Little Pigs' as an example, and assumed that the children are quite young. A considerably more difficult text might be used with teenagers, one far beyond their reading-age, but not beyond their comprehension, if all the references, metaphors and irony are explained.

(Older, well-read people tend to forget, I think, about the perfectly natural gaps in the knowledge of younger folk.)

Students highlight words and word-groups. My cousin asks his students to identify ‘Who or What’ words in red, ‘Process’ words in green, and ‘Circumstance’ words in blue.

Once upon a time there were three little pigs.

The little redhen and her threechicks baked a cake.

(Not having studied with Alan, I may not have this quite right, but you get the idea.)

Students would be given detailed help with each of the above sentences. 'Now this sentence says that the little red hen and her three little chicks baked a cake. What's a cake? How do you bake one, do you know? (Either the students or the teacher explain these things.)

'Now, what was it they baked? Yes, a cake! Can you find the word, 'cake' right at the end of the sentence? Can you find 'a cake'? Very good! Let's highlight that in red.'

Once students are more familiar with the text, the sentences are taken apart and played with. Words are cut out, moved around, and used to make new sentences – either on pieces of paper or a computer screen. The students are spared the chore of writing and can concentrate on the words.

Once upon a time there were three little pigs and three big wolves.

The little red hen and her three fluffy chicks baked a big chocolate cake with chocolate icing.

You can mix it up.

You can mix it up.Once upon a time there were three fluffy big wolves who baked a little chocolate hen.

My cousin tells me that his students enormously enjoy this, producing long, long sentences. The pigs can be little and pink and dirty, the wolves can be big and grey and hairy and fanged. The cake can have chocolate icing, and sprinkles, and candles, and cream and a red bow. Without realising it, by simple repetition and gentle correction, the students are learning how language bolts together. The little red hen can become a giant blue hen, or an enormous green cat. The chicks can be yellow as well as fluffy, and there can be three of them or three thousand.

Sentences can be turned round. A tasty chocolate cake was baked by three little chicks and a little red hen. There were three little pigs once upon a time.

Sentences can be formed by words on a card (or by dragging words about on a computer screen.

The farmer rides his horse.

The horse rides his farmer.

Such reversals cause great amusement - these games are fun!

The cards might have folding sections - or if the computer might offer a choice of other phrasings. You can then unfold a section - or drag in a phrase - to make:

The horse was ridden by the farmer

The farmer was riding his horse.

The more I learn about these methods, the more I learn how complex and demanding devising suitable teaching materials is - but with this approach, the onus is on the teacher to make learning easy and relaxed for the student. And it works!

Spelling is tackled by being broken into ‘startings’ and ‘endings.’

So you can take the starting, ‘str –‘ and add -eet, -ing, -ap, -ong.

To the starting 'ch', using cards or computer, you can add - ick, -urch, -um, -ap, -ina, -ip.

The teacher draws attention to these 'startings' and 'endings' repeatedly. Repeatedly. Drip, drip, drip. It's the teacher's job to take the trouble, not the student's job to memorise by rote.

The colour-coding and the use of images and games where words are moved to match the pictures exploit the fact that our memories are far more visual than verbal.

Once the students can all read the passage fluently and understand it, they move on to writing.

They are set the task of writing a passage closely based on the one they’ve studied in such detail. Notes are made on the board, and the students collaborate, supporting each other, and being supported by the teacher.

They discuss the purpose of their writing - remember, reading and writing are social activities. Is the purpose of their piece to instruct, to pass on factual information, or to describe atmosphere or feelings?

Using the notes, and working together, the students write their own version of the text.

Next they move on to individual writing. Working alone, they write their own version of the text they’ve worked on as a group. Stronger students may move to this stage earlier, while the teacher continues to help the weaker ones.

The final stage is Independent Writing. Here each student is set the task of writing a new passage, but one similar to that they’ve been working on - that is, a series of instructions or a description. They will use many of the words and phrases they have learned during the previous stages.

The students then move on to a new text, and the cycle above is repeated. Of course, many of the words and phrases they’ve already learned will be used in the new text, and the students’ knowledge will be reinforced. Their confidence will increase as they encounter words and phrases they recognise.

Alan Hess This method has been found highly effective in both Canada and Australia – and my cousin, Alan Hess, has seen for himself, over the last four years, what an improvement can be made in the standards of both literacy in students’ own language and the speaking and understanding of a foreign language.

Alan Hess This method has been found highly effective in both Canada and Australia – and my cousin, Alan Hess, has seen for himself, over the last four years, what an improvement can be made in the standards of both literacy in students’ own language and the speaking and understanding of a foreign language. In a relatively short time, it ‘ladders’ children up from having weak language and literacy skills to a point where they can ‘read to learn’ with confidence.

And also read for pleasure, of course. What writer could fail to be enthused by the idea of a growing market of eager readers?

Just for interest, here's a link to a fascinating Horizon programme about Michel Thomas and his teaching methods.

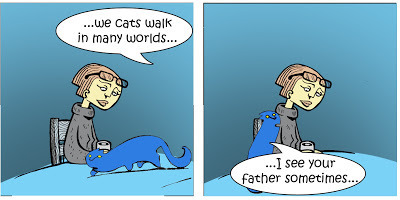

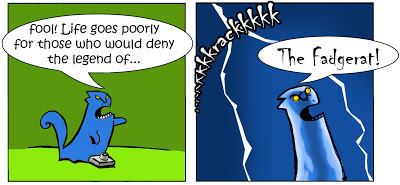

This week Blott is in memory of Alan George Price, 1928-2008.

Published on January 11, 2013 16:05

January 4, 2013

The Importance of Story

Okay, Christmas is over. Frivol is over. I want to return to the subject I was talking about before the mince-pies.

Okay, Christmas is over. Frivol is over. I want to return to the subject I was talking about before the mince-pies. Let’s be clear about one thing. Learning to read is hard.

I remember a friend, a very educated woman, talking about a branch of her family that she obviously didn’t waste much love on. She’d heard that a distant twig of this branch had become a teacher. “It’s the first I knew that they could read!” she said.

I’ve heard lots of variants on this joke. The subtext is: reading is easy, it’s kid’s stuff, something everyone can do. Therefore, if you can’t read, you’re stupid. I used to be a volunteer tutor at an Adult Literacy class, and I know how much this sneer hurts adults who find reading difficult.

And it’s based on a fallacy. Reading is very, very hard.

When someone immediately reads a sentence they’ve never seen before, they are, almost instantaneously, cracking a complex code, and converting shapes into sounds. A musician who sight-reads music is rightly admired, but someone who sight-reads a sentence is doing something only slightly less difficult. Because it’s a relatively common skill doesn’t make it easy. Driving averagely well is also a common skill, but no one assumes that’s it’s a doddle to learn or that it’s ’kids’stuff.’

When someone immediately reads a sentence they’ve never seen before, they are, almost instantaneously, cracking a complex code, and converting shapes into sounds. A musician who sight-reads music is rightly admired, but someone who sight-reads a sentence is doing something only slightly less difficult. Because it’s a relatively common skill doesn’t make it easy. Driving averagely well is also a common skill, but no one assumes that’s it’s a doddle to learn or that it’s ’kids’stuff.’ I’ve read that it takes about eight years to learn to read fluently. Because those of us who master the skill usually start very young, we tend not to remember its many difficulties. Those who don’t learn so quickly enter secondary school with a low reading age, and education for them becomes a worsening struggle. They’re made to feel failures, even if they are not told so outright. Hence the acute embarrassment often felt by my friends in the Adult Literacy Class.

Our education system expects children to enter secondary school with a reading-age matching their chronological age, and, in secondary school you don’t ‘learn to read,’ you ‘read to learn.’

If you can’t read, your formal education more or less comes to a halt. Schools become Aversion Therapy Units, putting children off education for life.

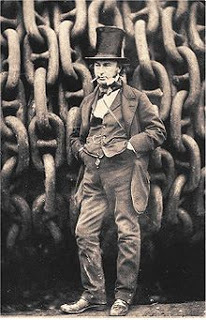

Brunel I have always revelled in the knowledge that if something interests me – Neanderthals, say, or brochs or rievers – ‘there’ll be a book on it.’ If I hadn’t been one of the lucky ones who went through school with a high reading age, I probably wouldn’t even have heard of most of the things that interest me. And though I haven’t done much with my fluent reading, how can we ever know what potential is being lost in the thousands of children we fail to teach to read fluently? How many mute inglorious Miltons and potential Brunels are we throwing away? It’s a huge waste and a national shame.

Brunel I have always revelled in the knowledge that if something interests me – Neanderthals, say, or brochs or rievers – ‘there’ll be a book on it.’ If I hadn’t been one of the lucky ones who went through school with a high reading age, I probably wouldn’t even have heard of most of the things that interest me. And though I haven’t done much with my fluent reading, how can we ever know what potential is being lost in the thousands of children we fail to teach to read fluently? How many mute inglorious Miltons and potential Brunels are we throwing away? It’s a huge waste and a national shame. Before Christmas, I was blogging about some of the teaching methods being developed, based on Michael Halliday’s theories. These methods aim to bridge the skill-gap between children who start school with thousands of hours of experience with books and language, and those children who start with much less.

One way is for schools to provide the experience that might be lacking at home. Instead of being constantly tested and graded, children should be read to, and told stories. Poems should be learned, songs sung.

I’ve heard adults say children ‘waste their time in school. They only listen to stories.’

Hearing stories is not a waste of time. Stories have, for millennia taught communication. They enlarge vocabulary and range of expression. A child who learns how to structure a fairy-story will understand better, years later, how to structure an essay – and even, how to order their own thoughts to make better decisions.

And all this story-telling and poetry listening should be as pleasurable as possible – because, if it isn’t, then the children switch off their brains, and you’re wasting your time and breath.

Indeed, that’s one of the reasons that story-telling has been used, for millennia, as a teaching aid – to gain attention, to hold attention, and to be memorable. (The Good Samaritan, for instance, The Ant and the Grasshopper – even The Little Engine Who Could.)

I quote the Ontario Ministery of Education (these methods have been successful in Canada.) ‘Becoming a reader is a continuous process that begins with the development of oral language skills and leads, over time, to independent reading. Oral language – the ability to speak and listen – is a vital foundation for reading success.’

Illustration: Kai Nielsen And where that foundation hasn’t been provided at home, the school must provide it. Tell them stories! The Brothers Grimm, The Little Red Hen, The Gingerbread Man. That masterpiece of suspense, The Billy Goats Gruff.

Illustration: Kai Nielsen And where that foundation hasn’t been provided at home, the school must provide it. Tell them stories! The Brothers Grimm, The Little Red Hen, The Gingerbread Man. That masterpiece of suspense, The Billy Goats Gruff. This is not ‘just play.’ This is not ‘wasting time.’ The frequent hearing and discussion of these old stories extends vocabulary, and demonstrates a whole spectrum of possible emotions and responses, from grief to gratitude, from rage to forgiveness, from fortitude and determination, to despair, to devotion. They teach pronunciation, rhythm, alliteration – and various modes of speech, from the everyday to the archaic and formal. Stories do all this, and more, and they do it pleasurably, so that children beg for more.

Gradgrind was, as Dickens pointed out, wrong. Stories are not mere entertainment, they are not a waste of time.

Story-telling is the seed-bed of eloquence and literacy.

And here's Blott in 'Twelfth Night.'

Published on January 04, 2013 16:05

December 28, 2012

In Conversation with... Ian Parks

Today, I'm talking with Ian Parks, a most likeable chap, who I met when he took over from me as Royal Literary Fellow at De Montfort University.

Sue Price: The impulse to write something, for me, is always connected to a story. There's always a 'What would happen if - ?' The story might extend itself to include beautiful descriptions, musings on the meaning of life, and so on - but it always begins with a story, and the story is always the backbone.

Sue Price: The impulse to write something, for me, is always connected to a story. There's always a 'What would happen if - ?' The story might extend itself to include beautiful descriptions, musings on the meaning of life, and so on - but it always begins with a story, and the story is always the backbone.

So poetry mystifies me a bit. Most of the poetry I like - that makes my hair stand up - doesn't tell a story at all. (Though I'm very fond of The Scholar Gypsy, by Mathew Arnold, which does.) I can't understand where you start with a poem. Can you tell me? Where does the first impulse come from?

Ian Parks

Ian Parks

Ian Parks:The poem begins as a feeling and not an idea. For me at any rate.

Certain words might circulate around an experience or an emotion. Sometimes that's as far as it gets, but if the individual words spark associations, and if those associations generate more language then we're looking at a first draft. Unless you're a narrative poet - in which case you're more likely to be led by similar considerations as a fiction writer.

For me, notions of what the poem might be 'about' don't start to arise until most of it is written. In that sense, the poet can only see the picture as it emerges. Every poem follows a different trajectory. Keats famously said that poetry should come as natural as leaves to a tree - and then drafted and re-drafted tirelessly until he made his work look as if it involved no work at all. I don't think that was merely to 'get it right'; rather, I guess he was feeling his way intuitively into what the poem might mean, what sort of shape it might make on the page and in the mind.

The metaphor I hold in my mind is one of something coming to the surface: you perceive it to be there but only gradually grasp its dimensions and its implications. It's difficult to trace the poem back to its origins which are often subsumed in a pre-language state'; that is, the poem begins in the heart and relocates to the head. Finally it ends up on the page where it takes on a strange, unpredicatable life of its own. When I look back on poems I wrote twenty years ago I can't remember where they came from.

Susan Price's Ghost Drum Sue Price: I sort of know what you mean. That is, I’m familiar with a finished work having meanings that I, as the writer, never knew were there. When I wrote ‘Ghost Drum’ I was only conscious of ‘making up’ the kind of scary fairy-story I’d always liked myself, with a wintry Russian setting, and witches, shape-shifting bears and ghosts. When I finished it and read it, I saw all kinds of meanings in it – the imprisoned hero, in his dome room at the top of a tower, locked inside for life – was that a metaphor for the way we’re each imprisoned in our own skulls? And the magic in the story was the magic of creativity – of words and music.

Susan Price's Ghost Drum Sue Price: I sort of know what you mean. That is, I’m familiar with a finished work having meanings that I, as the writer, never knew were there. When I wrote ‘Ghost Drum’ I was only conscious of ‘making up’ the kind of scary fairy-story I’d always liked myself, with a wintry Russian setting, and witches, shape-shifting bears and ghosts. When I finished it and read it, I saw all kinds of meanings in it – the imprisoned hero, in his dome room at the top of a tower, locked inside for life – was that a metaphor for the way we’re each imprisoned in our own skulls? And the magic in the story was the magic of creativity – of words and music.

I’d followed the images, the pretty metaphors, and found words for them without stopping to think what they might mean.

Is that something like what you mean when you say that the meaning of a poem is something that doesn’t arise until it’s written?

Ian: That's it, yes... I was leading a poetry writing workshop the other day and we were taking a close look at Thomas Kinsella's worksheets for his poem, Mirror in February. It's obvious that he put a lot of hard work into developing that poem, trying to follow its lead rather than imposing his own ideas onto it. Apart from the fact that they were amazed at how many drafts Kinsella had gone through (there are twelve) most of the people there were heartened to see that arriving at a finished poem can often be a struggle; a struggle that goes on 'behind the scenes' as only the final version is released. The other striking thing about those worksheets is that the germ of the finished poem is in the first draft - if you can call a few scribblings on the page a draft! The process that goes on between first draft and finished poem represents the poet's attempt to articulate to others what has been there from the beginning. After all, a poem isn't an idea but, as I say in one of my poems a 'thing made out of words'. I think, too, that sound is very important here. A poem on the page is only half a poem, to paraphrase Dylan Thomas. And something of the impulse to write comes out of the tension that arises between what the poem might 'mean' in semantic terms and what it might 'mean' when it's voiced; the emotional sound of the poem. So: lots going on at all sorts of levels. Returning to your initial question, Sue... My feeling is that poems come out of nowhere - or appear to do - and that it takes effort and, sometimes, experience to haul them up into the light of day.

Ian: That's it, yes... I was leading a poetry writing workshop the other day and we were taking a close look at Thomas Kinsella's worksheets for his poem, Mirror in February. It's obvious that he put a lot of hard work into developing that poem, trying to follow its lead rather than imposing his own ideas onto it. Apart from the fact that they were amazed at how many drafts Kinsella had gone through (there are twelve) most of the people there were heartened to see that arriving at a finished poem can often be a struggle; a struggle that goes on 'behind the scenes' as only the final version is released. The other striking thing about those worksheets is that the germ of the finished poem is in the first draft - if you can call a few scribblings on the page a draft! The process that goes on between first draft and finished poem represents the poet's attempt to articulate to others what has been there from the beginning. After all, a poem isn't an idea but, as I say in one of my poems a 'thing made out of words'. I think, too, that sound is very important here. A poem on the page is only half a poem, to paraphrase Dylan Thomas. And something of the impulse to write comes out of the tension that arises between what the poem might 'mean' in semantic terms and what it might 'mean' when it's voiced; the emotional sound of the poem. So: lots going on at all sorts of levels. Returning to your initial question, Sue... My feeling is that poems come out of nowhere - or appear to do - and that it takes effort and, sometimes, experience to haul them up into the light of day.

___________________________________________

Ian said I could publish one of his poems here:

Beach Hut

It’s thirty years since I undid the lock

to spend a rented summer under glass –

a space no bigger than my bedroom now,

the skylight slanting, sunlight through the planks.

Blue meant a day for swimming in the sea;

grey for reading till the weather cleared.

One room where everything I needed was to hand:

bare floorboards, faded rug, sand in my hair

and in my jeans. It was a year of rioting,

of running battles through the city streets,

of looted shop-fronts, shattered glass,

cars overturned and burning in the road.

The rumour of it didn’t reach me there.

I spread my sheets, slept on the floor,

hung a rusted oil-lamp from the beam,

convinced the answer could be found

in solitude and in the distant sound

of waves as they came rippling to the shore.

The place was a ramshackle wreck

held up by a lick of yellow paint.

At night a big ship loomed against the sky

and from its bright and polished deck

someone I imagined lit a foreign cigarette

and smoked it slowly, leaning on the rail.

Just once I saw a torchlight flashing back.

But mostly it was dunes, resilient grass,

the dog-eared books I read then threw away –

the narratives I didn’t want to share.

The days grew shorter. Cold set in.

The beach huts emptied. I grew bored.

Rain drove in every morning from the sea.

I packed my rucksack, caught a train,

sped inland through a landscape changed

to find the world not waiting anymore;

back to the city with its new façade

and the headlines I’d ignored.

Here's a link where you'll find more about Ian and his poems.

And here's his book, Shell Island, on Amazon.

And here's his book, Shell Island, on Amazon.

And here's Blott.

Sue Price: The impulse to write something, for me, is always connected to a story. There's always a 'What would happen if - ?' The story might extend itself to include beautiful descriptions, musings on the meaning of life, and so on - but it always begins with a story, and the story is always the backbone.

Sue Price: The impulse to write something, for me, is always connected to a story. There's always a 'What would happen if - ?' The story might extend itself to include beautiful descriptions, musings on the meaning of life, and so on - but it always begins with a story, and the story is always the backbone.So poetry mystifies me a bit. Most of the poetry I like - that makes my hair stand up - doesn't tell a story at all. (Though I'm very fond of The Scholar Gypsy, by Mathew Arnold, which does.) I can't understand where you start with a poem. Can you tell me? Where does the first impulse come from?

Ian Parks

Ian ParksIan Parks:The poem begins as a feeling and not an idea. For me at any rate.

Certain words might circulate around an experience or an emotion. Sometimes that's as far as it gets, but if the individual words spark associations, and if those associations generate more language then we're looking at a first draft. Unless you're a narrative poet - in which case you're more likely to be led by similar considerations as a fiction writer.

For me, notions of what the poem might be 'about' don't start to arise until most of it is written. In that sense, the poet can only see the picture as it emerges. Every poem follows a different trajectory. Keats famously said that poetry should come as natural as leaves to a tree - and then drafted and re-drafted tirelessly until he made his work look as if it involved no work at all. I don't think that was merely to 'get it right'; rather, I guess he was feeling his way intuitively into what the poem might mean, what sort of shape it might make on the page and in the mind.

The metaphor I hold in my mind is one of something coming to the surface: you perceive it to be there but only gradually grasp its dimensions and its implications. It's difficult to trace the poem back to its origins which are often subsumed in a pre-language state'; that is, the poem begins in the heart and relocates to the head. Finally it ends up on the page where it takes on a strange, unpredicatable life of its own. When I look back on poems I wrote twenty years ago I can't remember where they came from.

Susan Price's Ghost Drum Sue Price: I sort of know what you mean. That is, I’m familiar with a finished work having meanings that I, as the writer, never knew were there. When I wrote ‘Ghost Drum’ I was only conscious of ‘making up’ the kind of scary fairy-story I’d always liked myself, with a wintry Russian setting, and witches, shape-shifting bears and ghosts. When I finished it and read it, I saw all kinds of meanings in it – the imprisoned hero, in his dome room at the top of a tower, locked inside for life – was that a metaphor for the way we’re each imprisoned in our own skulls? And the magic in the story was the magic of creativity – of words and music.

Susan Price's Ghost Drum Sue Price: I sort of know what you mean. That is, I’m familiar with a finished work having meanings that I, as the writer, never knew were there. When I wrote ‘Ghost Drum’ I was only conscious of ‘making up’ the kind of scary fairy-story I’d always liked myself, with a wintry Russian setting, and witches, shape-shifting bears and ghosts. When I finished it and read it, I saw all kinds of meanings in it – the imprisoned hero, in his dome room at the top of a tower, locked inside for life – was that a metaphor for the way we’re each imprisoned in our own skulls? And the magic in the story was the magic of creativity – of words and music. I’d followed the images, the pretty metaphors, and found words for them without stopping to think what they might mean.

Is that something like what you mean when you say that the meaning of a poem is something that doesn’t arise until it’s written?

Ian: That's it, yes... I was leading a poetry writing workshop the other day and we were taking a close look at Thomas Kinsella's worksheets for his poem, Mirror in February. It's obvious that he put a lot of hard work into developing that poem, trying to follow its lead rather than imposing his own ideas onto it. Apart from the fact that they were amazed at how many drafts Kinsella had gone through (there are twelve) most of the people there were heartened to see that arriving at a finished poem can often be a struggle; a struggle that goes on 'behind the scenes' as only the final version is released. The other striking thing about those worksheets is that the germ of the finished poem is in the first draft - if you can call a few scribblings on the page a draft! The process that goes on between first draft and finished poem represents the poet's attempt to articulate to others what has been there from the beginning. After all, a poem isn't an idea but, as I say in one of my poems a 'thing made out of words'. I think, too, that sound is very important here. A poem on the page is only half a poem, to paraphrase Dylan Thomas. And something of the impulse to write comes out of the tension that arises between what the poem might 'mean' in semantic terms and what it might 'mean' when it's voiced; the emotional sound of the poem. So: lots going on at all sorts of levels. Returning to your initial question, Sue... My feeling is that poems come out of nowhere - or appear to do - and that it takes effort and, sometimes, experience to haul them up into the light of day.

Ian: That's it, yes... I was leading a poetry writing workshop the other day and we were taking a close look at Thomas Kinsella's worksheets for his poem, Mirror in February. It's obvious that he put a lot of hard work into developing that poem, trying to follow its lead rather than imposing his own ideas onto it. Apart from the fact that they were amazed at how many drafts Kinsella had gone through (there are twelve) most of the people there were heartened to see that arriving at a finished poem can often be a struggle; a struggle that goes on 'behind the scenes' as only the final version is released. The other striking thing about those worksheets is that the germ of the finished poem is in the first draft - if you can call a few scribblings on the page a draft! The process that goes on between first draft and finished poem represents the poet's attempt to articulate to others what has been there from the beginning. After all, a poem isn't an idea but, as I say in one of my poems a 'thing made out of words'. I think, too, that sound is very important here. A poem on the page is only half a poem, to paraphrase Dylan Thomas. And something of the impulse to write comes out of the tension that arises between what the poem might 'mean' in semantic terms and what it might 'mean' when it's voiced; the emotional sound of the poem. So: lots going on at all sorts of levels. Returning to your initial question, Sue... My feeling is that poems come out of nowhere - or appear to do - and that it takes effort and, sometimes, experience to haul them up into the light of day. ___________________________________________

Ian said I could publish one of his poems here:

Beach Hut

It’s thirty years since I undid the lock

to spend a rented summer under glass –

a space no bigger than my bedroom now,

the skylight slanting, sunlight through the planks.

Blue meant a day for swimming in the sea;

grey for reading till the weather cleared.

One room where everything I needed was to hand:

bare floorboards, faded rug, sand in my hair

and in my jeans. It was a year of rioting,

of running battles through the city streets,

of looted shop-fronts, shattered glass,

cars overturned and burning in the road.

The rumour of it didn’t reach me there.

I spread my sheets, slept on the floor,

hung a rusted oil-lamp from the beam,

convinced the answer could be found

in solitude and in the distant sound

of waves as they came rippling to the shore.

The place was a ramshackle wreck

held up by a lick of yellow paint.

At night a big ship loomed against the sky

and from its bright and polished deck

someone I imagined lit a foreign cigarette

and smoked it slowly, leaning on the rail.

Just once I saw a torchlight flashing back.

But mostly it was dunes, resilient grass,

the dog-eared books I read then threw away –

the narratives I didn’t want to share.

The days grew shorter. Cold set in.

The beach huts emptied. I grew bored.

Rain drove in every morning from the sea.

I packed my rucksack, caught a train,

sped inland through a landscape changed

to find the world not waiting anymore;

back to the city with its new façade

and the headlines I’d ignored.

Here's a link where you'll find more about Ian and his poems.

And here's his book, Shell Island, on Amazon.

And here's his book, Shell Island, on Amazon. And here's Blott.

Published on December 28, 2012 16:05

December 21, 2012

Old One-Eye Is Back!

Good Yule! Happy Solstice! This blog won’t be up again before Christmas, so this seems a good time to wish you all a happy mid-winter gathering and feast, call it what you will. As you can see, the Green Man has now made himself - or should that be Himself? - known. I wasn't going to give him eyes - I started off thinking that he should just be a mask - but then eyes seemed important. And then just one eye. Which makes it clear who He is - an appropriate visitor for this time of year, given all the drinking, and not just Mead of Poetry. There's much more I can do... I'm thinking of trying something like this,for his crown...

Salt would make good frost, maybe? For his photo-shoot, I stuck a black plastic tray to the door of a cupboard with blu-tak, and then stuck him to the tray. Oh the Holly and the Ivy, when they are both full-grown...

And not only is old One-Eye back - Blott is too!

Salt would make good frost, maybe? For his photo-shoot, I stuck a black plastic tray to the door of a cupboard with blu-tak, and then stuck him to the tray. Oh the Holly and the Ivy, when they are both full-grown...

And not only is old One-Eye back - Blott is too!

Published on December 21, 2012 16:05

December 14, 2012

A Walk on Walton Hill

The Clent Hills are a National Trust property on the edge of the Black Country, near Halesowen. There are two hills, Clent and Walton. This is the path up the side of Walton Hill on December 13th 2012.

The top of a fence-post.

The fence that the fence-post is part of. Climbing up Walton Hill.

The top of the hill. It was cold up there! The trees and grass to the right were all coated with ice, but to the right, ice-free.

A friendly little character we met on top of the hill. He was racing about with a yellow ball, begging everyone to throw it for him - well, all three of us daft enough to be up there in that weather. He didn't care whether we'd been introduced or not. He was looking towards me and grinning when I started to take the picture, but moved just as the shutter clicked. Never work with...

A friendly little character we met on top of the hill. He was racing about with a yellow ball, begging everyone to throw it for him - well, all three of us daft enough to be up there in that weather. He didn't care whether we'd been introduced or not. He was looking towards me and grinning when I started to take the picture, but moved just as the shutter clicked. Never work with...

The great icy piece of turf.

Coming back down the hill.

And the glasses of mulled cider in the pub afterwards.

Published on December 14, 2012 17:30

December 7, 2012

The Meaning of Mammoths

Here’s a little domestic scene for you.

Here’s a little domestic scene for you. A warm kitchen. The smell of baking. Sunlight spills through a window, lighting the bright scarlet petals of a potted geranium.

In the centre of the room, a mother has fastened her small child into a high-chair so it can’t get away, while she croons to it. “Conjugate the irregular verb, to be. I am, you are, he is, she is, they are. How do we form the past tense? I was, you were, he was, she was, they were. And the future tense? I shall be – or should we use ‘will’? I will be, you will be, he will be…’

This is how we all learned to speak our first language, isn’t it?

Or try this.

Mother (as she shows the child a banana): Do you want some banana? Do you? Banana? (Showing the banana again.) Banana. Mmm! (Pleased happy expression on her face, as she peels the banana.) Do you want a bite of banana? (Takes a bite of banana.) Mmm! Nice! Banana’s are nice! Do you want some? Do you want some? (Offering banana.)

By the end of the meal, the child recognises the word, ‘banana’ and knows what object it is linked to. It also has an idea of what ‘want’ means.

As far as I understand it (I don’t claim to be an expert) this is Functional Grammar in action. This is how we all learn our languages. (In exactly the same way my cat learned what the word 'brush' meant, after just two evenings, because he enjoyed being brushed so much. The word, the object and the experience united in his catty brain, never to be separated again.)

Because language isn’t about rules of grammar. It isn’t about plu-perfects and subjunctives. It’s about communicating between members of a social group. At perhaps its simplest – but certainly not least important – level, its purpose is to enable a child to tell its mother it’s hungry.

Language didn't evolve in classrooms, after all. It evolved on the savannah, and on the tundra. When it's cold and you're all hungry, it's vitally important to be able to tell your fellow gatherers exactly where that clump of reeds with the nutritious, starchy roots are to be found. And, when you're hunting a mammoth, who is pissed off, communicating the plan clearly to your fellow-hunters is more important than whether or not you split the infinitive. You might say that Traditional or Conventional Grammar is about proving how educated you are; and how well you've learned the rules - whereas language (and Functional Grammar) is about meaning and communication. (Though the meaning it communicates may well be more than the sense of the words: social standing, for instance.)

Language didn't evolve in classrooms, after all. It evolved on the savannah, and on the tundra. When it's cold and you're all hungry, it's vitally important to be able to tell your fellow gatherers exactly where that clump of reeds with the nutritious, starchy roots are to be found. And, when you're hunting a mammoth, who is pissed off, communicating the plan clearly to your fellow-hunters is more important than whether or not you split the infinitive. You might say that Traditional or Conventional Grammar is about proving how educated you are; and how well you've learned the rules - whereas language (and Functional Grammar) is about meaning and communication. (Though the meaning it communicates may well be more than the sense of the words: social standing, for instance.)‘Banana’ is a 'block of meaning.' In English, those sounds are attached to and signify a particular fruit.

‘Do you want’ is another block of meaning. It’s useful, because a great many other blocks of meaning can be clipped on to the end of it: an apple, a cup of tea, a sandwich, a pencil, a chair.

Do you want an apple?

a chair?

a cup of tea?

Mrs Price wants an apple

a chair

a cup of tea.

In learning language in this way, the child is far frompassive. It is not pinned in its high-chair (or behind a desk), memorising lists of vocabulary or learning rules about ‘describing words’ and ‘doing words’, because that's the task it's been given.

The child doesn't even know it's learning. It is thoroughly engaged and involved in the world around it. The child wants that banana. My cat really wanted to be brushed.

The child learns because that’s what interested, curious intelligent creatures do – especially if there’s some kind of reward involved, such as food, praise or respect. Learning, after all, is a survival trait.

Introducing boredom to learning is like dosing someone with a tranquiliser and then expecting them to learn as well and as easily.

We’ve all experienced it: trying to complete a boring task is the mental equivalent of trying to shift a heavy weight or wade through deep mud. We do it, when we have to; but boredom isn't the best aid to learning. Adding confusion doesn’t improve matters.

We’ve all experienced it: trying to complete a boring task is the mental equivalent of trying to shift a heavy weight or wade through deep mud. We do it, when we have to; but boredom isn't the best aid to learning. Adding confusion doesn’t improve matters.‘This form of a verb is typically used for what is imagined, wished or possible. It is usually the same as the ordinary or indicative, except in the third person singular, where the normal –s ending is omitted. In English this form usually denotes a formal tone.’ OED.None of you, of course, fail to recognise the subjunctive from this description. (What I want to know is, once you've removed the 'imagined, wished or possible,' what's left?)

More than one teacher of my acquaintance has told me that they’ve taught children who almost hear nothing from their families except, “Shut up,’ and ‘Get out my way.’ That's their vocabulary.

Another told me, ‘The children I teach get everything and nothing from their parents – everything in the way of designer clothes and expensive gadgets, and nothing in the way of attention or affection.” The vocabulary of these children is, 'Go away, I'm busy.'

I count myself hugely lucky to be able to say of my parents that they gave me everything and nothing – everything in the way of attention and affection, and nothing in the way of designer clothes and expensive gadgets.

Lucky children like me rapidly acquire ‘blocks of meaning’, and rapidly learn how these blocks can be taken apart and fitted together with other blocks, because the child hears these blocks of meanings used around it all the time. It observes how the people around it respond to these sounds. Often the blocks of meaning are carefully demonstrated to the child, as when a parent shows the child a toy, names the toy, and asks if the child wants it. (‘Here’s Teddy. Do you wantTeddy? Would you like to play with Teddy?)

The child finds that it can exert power over its surroundings and family by learning to ask for what it wants. The family reward the child by being pleased, and praising its efforts.

There may be some bargaining between the parent and child. ‘What’s the magic word? – Say ‘please’ first.’ – ‘If you’re good today, we may go to the park tomorrow.’

They also teach the child that there are different ways of speaking - that 'I want' is good enough for Mum and Dad, but 'Please may I - ?' and 'Thank you,' must always be used with other people. The child may be told, 'That's a naughty word. Daddy and Mummy may say it when they're angry, but you must never say it.'

This is not merely Mummy and Daddy being mealy-mouthed. This is Mummy and Daddy teaching their child that social communication has many variations, and you must often change your words to suit the context. An example: a man entering pub is greeted with a shout of, "You (Expletive deleted.") The shout may have come from an enemy or his greatest friend. The meaning is entirely dependent on context - and might not be acceptable anywhere other than the pub.

The children we call 'bright' are often those children lucky enough to live in a stimulating environment, where there is a lot to interest them, and where their interest is rewarded and stimulated anew. ‘You like the cat?” says the parent. ‘Then let’s look at lions, tigers, leopards – let’s mention the Ancient Egyptions worshipping them – and let’s have a look at wolves and elephants for good measure.’ It doesn’t really matter whether the child remembers all it's told – sufficient that it is interested, and finds learning to be a positive, rewarding experience that it will be eager to engage in again.

The children we call 'bright' are often those children lucky enough to live in a stimulating environment, where there is a lot to interest them, and where their interest is rewarded and stimulated anew. ‘You like the cat?” says the parent. ‘Then let’s look at lions, tigers, leopards – let’s mention the Ancient Egyptions worshipping them – and let’s have a look at wolves and elephants for good measure.’ It doesn’t really matter whether the child remembers all it's told – sufficient that it is interested, and finds learning to be a positive, rewarding experience that it will be eager to engage in again. But the question is, when you meet a bright, chattery child, who gleefully lectures you on dinosaurs or the habits of ants – is it because that child is ‘naturally’ more intelligent than its ‘duller’ neighbour who doesn’t even know what dinosaurs are?

And if that's so, how do you explain that the child who can't remember anything taught in class, can effortlessly learn countless categories of Packemon creatures?

Is the difference, perhaps, entirely due to the amount of encouragement and stimulus the child receives from its social group, whether that's its family or its peer-group in the playground?

And what is the best way, in formal education, of teaching both these children to read, and speak another language?

***

Blott is away for the next two weeks, sunning himself in Egypt.

But here - to please Madwippet - is a clip of Functional Grammar in action. Betsy has mastered 300 words and their meanings!

Betsy's owners, we're told, didn't initially try to train her. They found that she picked up the names of objects and associated them with the object simply by observation and repetition... It's estimated that she has the intelligence of, at least, a 2-year old child.

And, if you're interested, you can find more about Functional Grammar, and teaching material here

Published on December 07, 2012 16:05

November 30, 2012

Learning To Read On The Day You're Born

I remember my mother being horrified by a woman she met at a bus-stop, who complained that her ten year old son’s school was always ‘belly-aching’ about his low reading age. “What’s the matter with ‘em?” the woman asked. “He’s got until he’s sixteen to learn to read.” The woman shared what it seems is a common view – that reading is something learned during school hours, beginning at the age of five. I shared this view until recently. I believed I started learning to read when I began school I picked up reading as rapidly as it’s possible to do so. I don’t remember having any difficulty with it. Even such traps as ‘ough’ being pronounced ‘off’, ‘ow’ and ‘uff’ in different words didn’t hold me up for long, so eager was I to be able to read stories for myself. I was a very bright kid, eh? Ten out of ten, a gold star and a tick for me! Well, I was a bright kid, but I now think that my ease in learning to read had little to do with my being bright, nor did I start learning when I began school.

I remember my mother being horrified by a woman she met at a bus-stop, who complained that her ten year old son’s school was always ‘belly-aching’ about his low reading age. “What’s the matter with ‘em?” the woman asked. “He’s got until he’s sixteen to learn to read.” The woman shared what it seems is a common view – that reading is something learned during school hours, beginning at the age of five. I shared this view until recently. I believed I started learning to read when I began school I picked up reading as rapidly as it’s possible to do so. I don’t remember having any difficulty with it. Even such traps as ‘ough’ being pronounced ‘off’, ‘ow’ and ‘uff’ in different words didn’t hold me up for long, so eager was I to be able to read stories for myself. I was a very bright kid, eh? Ten out of ten, a gold star and a tick for me! Well, I was a bright kid, but I now think that my ease in learning to read had little to do with my being bright, nor did I start learning when I began school.

Michael Halliday In fact, most credit is due to my mother, and her surprising grasp of Functional Grammar (despite never having heard of it.) I’ve been hearing a lot about Functional Grammar lately, mostly from my cousin, Alan Hess, who teaches English in German speaking Switzerland. (You can see Alan's blog about FG here.) Functional Grammar is based on the ideas of Michael Halliday, and aims to teach foreign languages – and that foreign language of shapes called ‘reading’ – in the same way we all learned our first language. That is, by constant repetition and encouragement, by constant gentle correction, and the example of our peers and elders. We are, above all, social beings. We all want to fit in, to some extent, even the loners among us. Among ‘the lads’ a young man will swear, fart and swagger, to fit in. But that same young man, at his grandmother’s funeral, is very unlikely to behave in the same way. Instead, he will be demure and polite – to fit in. Language and reading, like getting rat-arsed and attending funerals, are social activities. Reading is a social activity too. I did not start learning to read at school, aged five. I started learning to read as soon as I could sit up, when my mother put a drawing pad in front of me, wrapped my fingers around a crayon, and showed me how to draw a cat. She also let me play with books (though she considered them almost sacred objects.) She let me use them as building blocks and tunnels for toy cars. So I learned that books were every day play-things. She bought me books and read aloud to me every day, following the words with her finger as I watched. Together we studied the pictures and talked about them. I learned that reading and being read to were pleasurable activities. And also, that enjoying books and reading was a way to please my mother. Both my parents loved books. Our house was crammed with reading, with bookcases to the ceiling in all rooms, and books piled on the stairs, on window-sills, under beds. My father read aloud to me too – he used to read out extracts from Jerome K Jerome. If I asked him one of my endless questions, he would often answer it by taking down a book. So I learned that reading was an adult thing I could aspire to: and that the answers to most questions could be found in books.

Michael Halliday In fact, most credit is due to my mother, and her surprising grasp of Functional Grammar (despite never having heard of it.) I’ve been hearing a lot about Functional Grammar lately, mostly from my cousin, Alan Hess, who teaches English in German speaking Switzerland. (You can see Alan's blog about FG here.) Functional Grammar is based on the ideas of Michael Halliday, and aims to teach foreign languages – and that foreign language of shapes called ‘reading’ – in the same way we all learned our first language. That is, by constant repetition and encouragement, by constant gentle correction, and the example of our peers and elders. We are, above all, social beings. We all want to fit in, to some extent, even the loners among us. Among ‘the lads’ a young man will swear, fart and swagger, to fit in. But that same young man, at his grandmother’s funeral, is very unlikely to behave in the same way. Instead, he will be demure and polite – to fit in. Language and reading, like getting rat-arsed and attending funerals, are social activities. Reading is a social activity too. I did not start learning to read at school, aged five. I started learning to read as soon as I could sit up, when my mother put a drawing pad in front of me, wrapped my fingers around a crayon, and showed me how to draw a cat. She also let me play with books (though she considered them almost sacred objects.) She let me use them as building blocks and tunnels for toy cars. So I learned that books were every day play-things. She bought me books and read aloud to me every day, following the words with her finger as I watched. Together we studied the pictures and talked about them. I learned that reading and being read to were pleasurable activities. And also, that enjoying books and reading was a way to please my mother. Both my parents loved books. Our house was crammed with reading, with bookcases to the ceiling in all rooms, and books piled on the stairs, on window-sills, under beds. My father read aloud to me too – he used to read out extracts from Jerome K Jerome. If I asked him one of my endless questions, he would often answer it by taking down a book. So I learned that reading was an adult thing I could aspire to: and that the answers to most questions could be found in books.

So is it any wonder that, at five, when I began school, I was powerfully motivated to learn to read? And that I approached reading lessons with the most positive of attitudes. Reading, after all, was not strange or difficult – it was something that my parents did every day, with great enjoyment. Gimme that John and Janet book! I’m going to crush reading! I was fitting in with my social group - my family. There are few more powerful spurs to learning a particular behaviour. My parents followed my reading progress with great interest, and encouraged, applauded and boasted about it. I was rewarded with stories, which I loved, and with more books. Is it any wonder I rapidly improved? In fact, my whole upbringing was designed to produce a child who wanted to read, and found it easy to learn. The hours spent drawing with my mother had practiced me in observing and memorising shapes. The hours of listening to stories had familiarised me with the shapes and sounds of many words, with narrative conventions and common phrases – which enabled me to guess at whole phrases from their context. Because I had been read to so much, I started school with a larger vocabulary than most five year olds. My parents' approval gave me a strong incentive. And, at a certain point, reading becomes its own reward – The Little Mermaid, (Far out in the ocean, where the water is as blue as the prettiest of cornflowers and as clear as crystal…) The Jungle Books, Black Beauty… By contrast, I always struggled with maths – and so did my mother. Her attitude was, ‘I was always hopeless at maths. You’ve got that from me.’ I gave up on maths, much as she did. Now, in the light of Functional Grammar, I think this is more than a coincidence. Maths didn't offer me the same incentive scheme! Now remember that boy who had until he was sixteen to learn to read? I wonder what the attitude to books and reading was in his home? It’s very likely that there were no books in his house, and that he was never read to, or told stories. So when he began school, he was already handicapped compared to children from homes like mine. He had no familiarity with paper and pencils, no familiarity with the shapes of letters, or with phrases such as, ‘Once upon a time there was…’ For him books were objects kept at school, and given out during lessons. Reading books was something that his family didn’t do. It was a difficult, and therefore wearisome, chore that he was made to do at school – a humiliating task that he stumbled through while the teacher criticised and bored classmates yawned. He would have struggled to see the point of it. And in rejecting reading and finding it 'boring' and 'stupid,' he was fitting in with his social group, his own family who, judging by his mother's bus-stop conversation, placed no importance on reading. Yet, when he was slow to master reading at school, he was labelled 'less able' and 'less academic' (and quite likely, in the privacy of the staff-room, a 'thicko'.) In fact, he was probably just as able, intellectually, to learn reading as I was, had he only recieved the same incentive, encouragement and reward from his social group. You learn to read when you go to school? – No. You start learning to read on the day you’re born.

So is it any wonder that, at five, when I began school, I was powerfully motivated to learn to read? And that I approached reading lessons with the most positive of attitudes. Reading, after all, was not strange or difficult – it was something that my parents did every day, with great enjoyment. Gimme that John and Janet book! I’m going to crush reading! I was fitting in with my social group - my family. There are few more powerful spurs to learning a particular behaviour. My parents followed my reading progress with great interest, and encouraged, applauded and boasted about it. I was rewarded with stories, which I loved, and with more books. Is it any wonder I rapidly improved? In fact, my whole upbringing was designed to produce a child who wanted to read, and found it easy to learn. The hours spent drawing with my mother had practiced me in observing and memorising shapes. The hours of listening to stories had familiarised me with the shapes and sounds of many words, with narrative conventions and common phrases – which enabled me to guess at whole phrases from their context. Because I had been read to so much, I started school with a larger vocabulary than most five year olds. My parents' approval gave me a strong incentive. And, at a certain point, reading becomes its own reward – The Little Mermaid, (Far out in the ocean, where the water is as blue as the prettiest of cornflowers and as clear as crystal…) The Jungle Books, Black Beauty… By contrast, I always struggled with maths – and so did my mother. Her attitude was, ‘I was always hopeless at maths. You’ve got that from me.’ I gave up on maths, much as she did. Now, in the light of Functional Grammar, I think this is more than a coincidence. Maths didn't offer me the same incentive scheme! Now remember that boy who had until he was sixteen to learn to read? I wonder what the attitude to books and reading was in his home? It’s very likely that there were no books in his house, and that he was never read to, or told stories. So when he began school, he was already handicapped compared to children from homes like mine. He had no familiarity with paper and pencils, no familiarity with the shapes of letters, or with phrases such as, ‘Once upon a time there was…’ For him books were objects kept at school, and given out during lessons. Reading books was something that his family didn’t do. It was a difficult, and therefore wearisome, chore that he was made to do at school – a humiliating task that he stumbled through while the teacher criticised and bored classmates yawned. He would have struggled to see the point of it. And in rejecting reading and finding it 'boring' and 'stupid,' he was fitting in with his social group, his own family who, judging by his mother's bus-stop conversation, placed no importance on reading. Yet, when he was slow to master reading at school, he was labelled 'less able' and 'less academic' (and quite likely, in the privacy of the staff-room, a 'thicko'.) In fact, he was probably just as able, intellectually, to learn reading as I was, had he only recieved the same incentive, encouragement and reward from his social group. You learn to read when you go to school? – No. You start learning to read on the day you’re born.

Published on November 30, 2012 16:05

November 23, 2012

In Conversation With Jenny Alexander...

Sue Price: Jenny, when we’ve talked before, it seemed that we were approaching the same place from opposite directions. Your experiences made you sensitive to dreams and your unconscious life, and in exploring that, you moved towards writing... Whereas I started in a sceptical place, denying any such nonsense as 'the subconscious' or 'meaningful dreams' but, in writing more, was forced to acknowledge both the power of the subconscious and the truth often found in dreams.

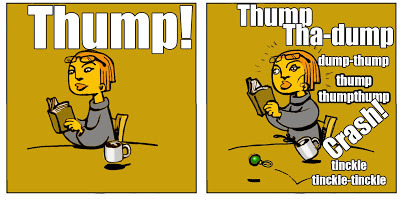

Would you agree with that? - and could you tell us more about how you began your dream-work and writing? Jenny Alexander: Yes, I would absolutely agree, Sue - it was an interesting conversation! All through my childhood I wanted to be a poet or an artist - writing and painting were my passions. But I finally yielded to pressure to apply for university rather than art school, and gave up my artistic ambitions. After a while at uni, learning to dissect a text with brutal efficiency, I gave up on writing too. Sue Price: That is so sad! It must have been torture! Jenny Alexander: At that point, I had a series of nightmares about killing myself. I would put my finger in a light socket and flick the switch, or turn on the gas fire in my student room and not light the gas. These dreams felt totally real and terrifying. One night, in my dream, I climbed out onto the ledge outside my room, and sat looking down at the cold concrete four floors below, gearing myself up to jump. I woke to find that I really was there. I had opened the sash window and climbed out in my sleep. Shaking violently, I somehow managed to clamber back in. Later that morning, I told my doctor, 'I think my dreams are trying to kill me.' I felt that I had no choice but to engage with my dreams, and over the next two decades, I became thoroughly familiar with my dream-world, so that when I was ready to think about becoming an author again, there was no anxiety or self doubt, because I knew I had inside myself this abundant, continuous flow of stories and images, and I knew how to capture them. Could you say a bit about how your writing became an opening into the dreamworld, as I call the unconscious mind, for you? Sue Price: Your dreams were trying to kill you! That strikes a chord with me, because there was a time in my life, when I was denying that ‘other’ in my head, when I think my subconscious very deliberately worked against me, although it wasn’t as murderous as yours! For instance, I would say something quite innocent to someone – something like, ‘How are you?’ - and hear myself saying it in a way that made it insulting. I had absolutely no conscious intention of insulting anyone, and would be as astonished as the person I’d just offended. But what could I say? I’d just bitten their heads off for no good reason! It was impossible to explain that it wasn’t me who’d said it! They’d have thought I was mad. Occasionally, I thought I was mad. I was at logger-heads with what I now call ‘my daemon’ because I was refusing to acknowledge that it existed. It fought me all the way. I’d be writing something and would decide to make some change to the plot. The ‘daemon’ would object, but I didn’t recognise its voice and took it for a mere passing thought, which I’d ignore because I had my plan. I was certain there was only one voice in my head: the ‘I’ voice, which I would now call ‘the editor’. The daemon took revenge by withdrawing. The piece of writing I was working on would fall over dead. I had to learn that with writing – or, I think, any art – the daemon does the real work! The Editor may make some great improvements, once the real work is finished, but shouldn’t be allowed to interfere with the daemon. A vengeful, spurned daemon is a dangerous thing, I think – especially yours! Mine not only stymied my efforts at writing, it played those tricks to embarrass me. It was ingenious at finding ways to make such remarks as, “Yes, please,” or “I’ve heard of that,” nasty and cutting. I had to learn that talk of ‘muses’ and ‘daemons’ was not the arty-farty nonsense I thought it, but a way of talking about something that we don’t quite understand, and don’t have an everyday vocabulary for. I began to deal with writing-problems by saying to the daemon, ‘Solve this for me.’ And it did! The more I trusted it, the faster and more inventively it solved the problems. I started to give way to it. If it insisted that a particular character should – or shouldn’t – die, I no longer argued, but humbly worked with it to make it so. I discovered that the more I trusted the daemon, the friendlier it became. It stopped playing those tricks on me! So I paid more attention and ‘heard’ it more clearly. I saw how a piece of writing I’d ‘made up as I went along’ had sub-texts planted in it, and other subtleties that ‘I’ hadn’t planned – so who had? And then I read Kipling’s description of his ‘daemon’ and knew what he was talking about right away. It seems that your ‘daemon’ was so furious at your moving away from your art – or so despairing – that it wanted to kill you. That’s frightening. Do you think it was drawing and writing again that made your peace with it? Jenny Alexander: Well, that was not what I expected, Sue! All my struggles with the daemon were fought within the inner world of dreams, in a quite elemental way, long before I came back to writing at the age of forty. So I hadn't imagined what it would feel like to have to learn to stop fighting and 'humbly work with it' through the process of becoming a writer. I knew that must happen, and I've watched other writers struggle to let go of the ego position and begin to trust in the ‘somewhere else’ where the real movement and growth of the story happens outside conscious control, in its own time and at its own pace. But I hadn't imagined it, and your description conjures it very vividly, and also the taming of the 'I' in the outer world by these dark forces pushing through and disrupting things. I met my dark forces in dreams. That's where I learnt the language of symbols and stories, and developed a relationship with them which turned out to be the perfect grounding for a confident and happy experience of writing, and that is certainly how I would describe my career so far. Thinking about your story, I'm wondering whether this awareness and conscious working with the daemon, which started in the outer world and continued into your writing, is continuing to carry you towards new ideas and ways of being? Sue Price. I am always amazed by how many ways there are to write! I had no idea I was letting go of the ego position. It felt – and still feels, often – as if I’m listening to another voice, or being handed an image and ordered to write about it, or almost physically nudged towards an idea. Or pushed away from one! Very much like the voice which all but spoke to me as I woke and said, ‘Make a Green Man mask out of papier-mache.’ I’m obediently making it and I still don’t know why! I’m enjoying it, so I carry on. But is it carrying me towards new ideas and ways of being? I don’t think so! For all this talk of daemons and ‘voices’, I continue to be as spiritual as a brick. I am essentially, I think, pragmatic. If something works, use it. I wanted to write, so I used whatever seemed to work, but without, if I’m honest, ever thinking very deeply about it. Unlike you! I am fascinated by your struggles and fights in the’ inner world of dreams.’ This sounds so much like what I read about shaman’s spirit travels and I imagined for my Ghost World books. It’s quite startling to hear someone talking matter of factly about fighting battles in dreams. I think we’re out of space for now – but I would love to hear more about this inner world and the battles you fought, if you wouldn’t mind talking about them. Perhaps we could continue this conversation another time? Jenny Alexander: Absolutely! And in the meantime, how about being 'in conversation with' that Green Man? It would be interesting to know why he's come and what he wants... Susan Price: There's a thought! I'm not sure I'd get an answer - or if I'd want to hear it if I did! Jenny Alexander is a highly respected author for children, as well as an expert dream-wrangler! Her website can be found here. Her excellent blog, about dreams and creativity, can be found here. I apologise for the failure of the blog last week. This Blott would have been nearly topical then! But I post it, because I like it. It demonstrates the dangers of excitable and uncontrolled daemons/muses!

Published on November 23, 2012 16:05

November 16, 2012

Learning To Read From The Day You're Born

I remember my mother being horrified by a woman who complained that her ten year old son’s school were always ‘belly-aching’ about his low reading age. “What’s the matter with ‘em?” the woman asked. “He’s got until he’s sixteen to learn to read.” The woman shared what it seems is a common view – that reading is something learned during school hours, beginning at the age of five. I shared this view until recently. I believed I started learning to read when I began school at five. I picked up reading as rapidly as it’s possible to do so. I don’t remember having any difficulty with it. Even such traps as ‘ough’being pronounced ‘off’, ‘ow’ and ‘uff’ in different words didn’t hold me up for long, so eager was I to be able to read stories for myself. I was a very bright kid, eh? Ten out of ten, a gold star and a tick for me! Well, I was a bright kid, but I now think that my ease in learning to read had little to do with my being bright, nor did I start learning to read when I began school. In fact, most credit is due to my mother, and her surprising grasp of Functional Grammar (despite never having heard of it.)I’ve been hearing a lot about Functional Grammar lately, mostly from my cousin, Alan Hess, who teaches English in German speaking Switzerland. Functional Grammar is based on the ideas of Michael Halliday, and aims to teach foreign languages – and that foreign language of shapes called ‘reading’ – in the same way we all learned our first language. That is, by constant repetition and encouragement, by constant gentle correction, and the example of our peers and elders. We are, above all, social beings. We all want to fit in, to some extent, even the loners among us. Among ‘the lads’ a young man will swear, fart and swagger, to fit in. But that same young man, at his grandmother’s funeral, is very unlikely to behave in the same way. Instead, he will be demure and polite – to fit in. Language and reading, like getting rat-arsed and attending funerals, are social activities. Reading is a social activity too. I did not start learning to read at school, aged five. I started learning to read as soon as I could sit up, when my mother put a drawing pad in front of me, wrapped my fingers around a crayon, and showed me how to draw a cat. She also let me play with books (though she considered them almost sacred objects.) She let me use them as building blocks and tunnels for toy cars. So I learned that books were every day play-things. She bought me books and read aloud to me every day, following the words with her finger as I watched. Together we studied the pictures and talked about them. I learned that reading and being read to were pleasurable activities. And also, that enjoying books and reading was a way to please my mother. Both my parents loved books. Our house was crammed with reading, with bookcases to the ceiling in all rooms, and books piled on the stairs, on window-sills, under beds. My father read aloud to me too – he used to read out extracts from Jerome K Jerome. If I asked him one of my endless questions, he would often answer it by taking down a book. So I learned that reading was an adult thing I could aspire to: and that the answers to most questions could be found in books.So is it any wonder that, at five, when I began school, I was powerfully motivated to learn to read? And that I approached reading lessons with the most positive of attitudes. Reading, after all, was not strange or difficult – it was something that my parents did every day, with great enjoyment. Gimme that John and Janet book! I’m going to crush reading! My parents followed my reading progress with great interest, and encouraged, applauded and boasted about it. I was rewarded with stories, which I loved, and with more books. Is it any wonder I rapidly improved? In fact, my whole upbringing was designed to produce a child who wanted to read, and found it easy to learn. The hours spent drawing with my mother had practiced me in observing and memorising shapes. The hours of listening to stories had familiarised me with the shapes and sounds of many words, with narrative conventions and common phrases – which enabled me to guess at whole phrases from their context. Because I had been read to so much, I started school with a larger vocabulary than most five year olds. And, at a certain point, reading becomes its own reward – The Little Mermaid, (Far out in the ocean, where the water is as blue as the prettiest of cornflowers and as clear as crystal…) The Jungle Books, Black Beauty… By contrast, I always struggled with maths – and so did my mother. Her attitude was, ‘I was always hopeless at maths. You’ve got that from me.’ I gave up on maths, much as she did. Now, in the light of Functional Grammar, I think this is more than simple inheritance, or a coincidence. Remember that boy who had until he was sixteen to learn to read? I wonder what the attitude to books and reading was in his home. It’s very likely that there were no books in his home, and that he was never read to, or told stories. So when he began school, he was already handicapped compared to children from homes like mine. He had no familiarity with paper and pencils, no familiarity with the shapes of letters, or with phrases such as, ‘Once upon a time there was…’ For him books were objects kept at school, and given out during lessons. Reading books was something that his family didn’t do. It was a difficult, and therefore wearisome chore that he was made to do at school – and he would have struggled to see the point of it. Reading was a humiliating task that he stumbled through while the teacher criticised and bored classmates yawned. You learn to read when you go to school? No. You start learning to read - or not - on the day you’re born.

Published on November 16, 2012 16:05

November 9, 2012

The Next Big Thing

Susan Price

Susan PriceI don't know who first had the idea for this, but it's become a bit of craze among on-line writers. First, you answer the ten questions below about your work-in-progress. Then you link to the blogs of other writers, about their work in progress. So, here goes -

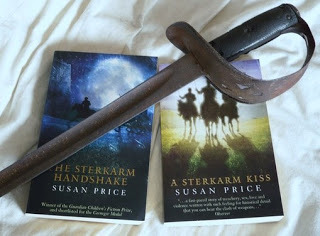

Q1. What is the working title of your book? I usually call it ‘Sterkarm 3’ because it will be the third Sterkarm book. But its official working title, at the moment, is ‘A Sterkarm Embrace.’ It’s also been called, ‘A Sterkarm Cure’ and ‘A Sterkarm Potion’. The title’s in progress too.

Sterkarm Handshake and Sterkarm KissQ2 where did the idea come from for the book? The second book in the Sterkarm series, ‘A Sterkarm Kiss’, ended in a cliff-hanger. This one takes the story on from there.

Sterkarm Handshake and Sterkarm KissQ2 where did the idea come from for the book? The second book in the Sterkarm series, ‘A Sterkarm Kiss’, ended in a cliff-hanger. This one takes the story on from there.Q3 What genre does your book fall under? The time machine makes it science-fiction or fantasy, but the realistic scenes set in the 16thCentury Border Lands make it historical. The love between 21stCentury Andrea and 16th Century Per make it a romance. All the fighting makes it an adventure. Is there a Science-fictionish Historical Romantic Adventure genre?