Susan Price's Blog: Susan Price's Nennius Blog, page 11

July 25, 2014

Lost In The Dunes

Knight: Lewis Chess Set

Knight: Lewis Chess SetLook at this little fella. Isn't he great?

I imagine most, if not all, of my readers will immediately recognise him - even without the caption - as a knight from the Lewis chessmen. The photograph above, though, was taken by me of one that sits on my shelf. It's a replica, quite a good one, I think, and it allows you to hold the little character in your hand and get a good close look at him.

He's very like a Norman (norse-man) knight, with his kite-shaped shield and his conical helmet with a nose-piece. His horse is a sturdy little beast - I think its size, proportionate to its rider, was probably accurately observed. (What do you think, Madwippet?) The rider has stirrups, and the horse has a caparison.

I only own two pieces. Here's the other: a Bishop.

Lewis chess men: the bishop

Lewis chess men: the bishopHe may look as if he's making a rude gesture, but I think it's a blessing. Here's the back of him, showing the beautiful carving of his elaborate chair, and mitre ribbons.

Lewis Chess men: the bishop's back side. I wish I owned more of them. I'd really like to have one of the berserkers who's biting his shield. And a Queen. And a King. Well, the whole set, really.

Lewis Chess men: the bishop's back side. I wish I owned more of them. I'd really like to have one of the berserkers who's biting his shield. And a Queen. And a King. Well, the whole set, really.The chessmen were found on the west coast of the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis, in 1831, one of history's great accidental finds.

There are several differing stories about how they were found. One says they were unearthed by a cow. The first I came across said that they were found in a sand-dune, in a little 'cave', and that the superstitious Highlander who found them, Malcolm Mcleod, was frightened and ran away, thinking he'd stumbled on a gathering of 'the little people' or fairies.

Lewis is to the left of Scotland, marked with a red dot I was always suspicious about this story: it assumed that a Highland crofter was a fool, and I'm pretty sure that if you want to find a fool among the Highland crofters, then or now, you'd have to take one with you.

Lewis is to the left of Scotland, marked with a red dot I was always suspicious about this story: it assumed that a Highland crofter was a fool, and I'm pretty sure that if you want to find a fool among the Highland crofters, then or now, you'd have to take one with you.If there was any truth in the tale at all, it sounded to me like a story Mcleod might have told to amuse his friends - and which was taken at face value by the antiquarian gentleman who later took an interest in the chessmen.

It seems I was right to doubt it. Far from being afraid of the chessmen, Mcleod exhibited them for a while in his byre, before selling them to a Captain Roderick Ryrie. (Mcleod's family were later evicted from their land during the Clearances, so I hope he drove a hard bargain.)

So, what is known about the pieces? Well, most of them are carved from walrus ivory, though a few are made from whales' teeth. Their manufacture has been dated pretty firmly to the 12th Century, in Norway, probably in Trondheim, where there was a market for such expensive, high-status articles, and where similar figures have been found. Dr. Alex Woolf, director of the Institute for Medieval Studies of the University of St. Andrews, argues that the armour worn by some of the figures is a perfect replica of that worn in Norway at the time.

There is some argument, however. Gudmundur G. Thórarinsson has published a paper which makes a case for the chessmen being made in Iceland. He points out that the chessmen are the oldest known to make a connection between the Church and chess, and that only two countries in the world call this piece 'bishop', and those countries are Iceland and Britain.

Some have also argued that the small horses ridden by the knights look like Icelandic horses.

Several of the chessmen - Wikimedia Commons

Several of the chessmen - Wikimedia CommonsThey're called 'the chessmen' rather than 'the chess set' because there are figures from more than one set. There are, altogether, 19 pawns (which look rather like standing stones), 8 Kings, 8 Queens, 16 bishops, 15 knights and 12 rooks. Some of them seem to have been stained red, suggested that Viking chess pieces were red and white, rather than black and white. As you can see in the photo above, the pieces differ quite a lot in size and style.

Probably the biggest mystery about them is why on earth so many pieces from several different, high quality, expensive chess sets were buried in a sand dune, in a little stone 'kist', beside a bay on a remote Outer Hebridean island.

Well, of course, in the 12th Century - and for most of the Viking Age preceding it - these islands weren't 'remote', as we think

of them. Take another look at that map. The Hebrides were ruled by Norway at the time - as were the Orkneys and Shetlands, and large parts of Scotland and Ireland. The Hebrides were in the middle of thriving maritime trade-routes, with ships coming and going from Scandinavia to Scotland, the Islands, Ireland, the Faroes, Iceland - and even Greenland and America. They traded in soapstone, timber, amber, walrus ivory and walrus hide - oh, and slaves. The Vikings were big in the slave-trade.

of them. Take another look at that map. The Hebrides were ruled by Norway at the time - as were the Orkneys and Shetlands, and large parts of Scotland and Ireland. The Hebrides were in the middle of thriving maritime trade-routes, with ships coming and going from Scandinavia to Scotland, the Islands, Ireland, the Faroes, Iceland - and even Greenland and America. They traded in soapstone, timber, amber, walrus ivory and walrus hide - oh, and slaves. The Vikings were big in the slave-trade.One theory - which seems pretty convincing - was that the chessmen were part of the stock-in-trade of some merchant travelling these whale-roads. He'd bought from craftsmen in Trondheim, and hoped to sell to wealthy jarls in Shetland, Orkney or the Isles. But that still leaves us wondering why he buried them in the sand dune on Uig Bay. What happened? Was he attacked by pirates? Did he hope to return and recover them? - they must have been worth quite a bit.

A friend suggests that perhaps the merchant was in debt, and hid these valuable items rather than see them taken in payment. And was then done in by the loan-shark before he could recover them. You have to admit, a Viking loan-shark is a pretty formidable notion.

For whatever reason they were hidden, they then stayed in the dark, in their little cave, for nearly 600 years.

They carry a lot of information, these little figures. Look at the Kings and Queens here. The Kings have different faces and different beards, though similar crowns and draperies. Both hold their swords across their knees. My friend suggested they were whetstones, ancient symbols of royalty - but I think, looking closely, they are swords. The kings seem to be holding a hilt at one end, and the carving suggests a scabbard. Sitting with a sword across their knees is how Viking kings and lords received vows of fealty.

Two each of the eight Kings and Queens - Wikimedia Commons

Two each of the eight Kings and Queens - Wikimedia CommonsThe Queens are dressed almost identically, and sit in a similar pose. Each has one hand pressed to her face - though one supports this hand by placing the other under her elbow, and one is holding a drinking horn. They teach us a lesson in being wary of thinking we understand the past, because these little figures seem comic to us. Do their woeful, pained expressions convey toothache or indigestion? Is the one with the drinking horn drunk? Are they thinking about household chores, or just fed up with being surrounded by drunken Vikings? (Spam, spam, spam, spam - spam, spam, spam, spam...)

Compassion and wisdom - not toothache. Wiki Commons In fact, they were surely never intended to be comic. Vikings took their chess seriously. The Queens' pose is part of a complex visual code that would have been understood at the time (just as we understand many of the poses and 'uniforms' used in that modern propaganda we call advertising.) The Queen's glum face, and hand to her cheek, convey compassion and mercy - with perhaps just a dash of wisdom. That was understood to be a Queen's job - to leaven her husband's demands for loyalty and fighting men, with a little gentleness and understanding.

Compassion and wisdom - not toothache. Wiki Commons In fact, they were surely never intended to be comic. Vikings took their chess seriously. The Queens' pose is part of a complex visual code that would have been understood at the time (just as we understand many of the poses and 'uniforms' used in that modern propaganda we call advertising.) The Queen's glum face, and hand to her cheek, convey compassion and mercy - with perhaps just a dash of wisdom. That was understood to be a Queen's job - to leaven her husband's demands for loyalty and fighting men, with a little gentleness and understanding.You can see the strips of 'tablet-weave' decorating the edges of the queen's sleeves and cape. These strips were woven in bright colours and patterns on small 'tablets' or miniature looms. And is that a striped under-sleeve, or a pile of many bracelets?

It's worth mentioning that the King, Queen and Bishop are seated in chairs to convey their high social status. They could just as easily have been carved standing. But no, the High-Ups didn't stand. They sat, in grand chairs with arms and high backs, while the hoi-polloi stood or knelt.

Here's possibly my favourite - one of the two 'warders' or, in

A Lewis berserkermodern terms, 'rooks', shown biting his shield in berserker rage. There's an argument about whether berserkers, or belief in them, ever existed in the Viking Age (6th-8th centuries AD), or whether it was a later fantasy. It's pointed out that there are no depictions of berserkers from the Viking Age itself - and the Lewis berserker, sadly, dates to the medieval period.

A Lewis berserkermodern terms, 'rooks', shown biting his shield in berserker rage. There's an argument about whether berserkers, or belief in them, ever existed in the Viking Age (6th-8th centuries AD), or whether it was a later fantasy. It's pointed out that there are no depictions of berserkers from the Viking Age itself - and the Lewis berserker, sadly, dates to the medieval period.Not all the warders are about to run mad. The one below is stalwart and on guard with sword and shield at the ready, but not even tempted to give his shield a nibble. These figures aren't meant to be comic either, however funny and cute they seem to us. They're meant to convey ferocity in battle, a readiness to fight for their lord - the one they swore fealty to while he held his sword across his knees - and die in his service, if necessary.

Perhaps one

Lewis Warderof the selling points of these chess men was that you could choose the figures you liked best - berserkers if your taste ran that way, or sober guards, if not. I imagine many figures spread out on the table of a jarl's hall - perhaps the jarl allowed his children to choose which warders, kings, queens and bishops he bought. Or, maybe you could buy replacements for pieces lost or broken?

Lewis Warderof the selling points of these chess men was that you could choose the figures you liked best - berserkers if your taste ran that way, or sober guards, if not. I imagine many figures spread out on the table of a jarl's hall - perhaps the jarl allowed his children to choose which warders, kings, queens and bishops he bought. Or, maybe you could buy replacements for pieces lost or broken?Maybe they were carved to order? If so, several people were left wondering what had happened to their ordered chess set. Runic letters were dispatched by ship to Trondheim: 'I ordered a chess set last Egg-Month, and now it's Blood Month and they still haven't come.'

My friend suggests that perhaps they were one massive chess-set, where players chose pieces according to their character or mood. "Tonight, Thorstein, I shall have the berserkers, the Queen with the drinking horn, the Bishop who's clutching his crosier as if he's going to bash somebody with it, and the King with the leer." It's an attractive idea, but I think the sizes of the pieces are too varied for them to be part of a single set.

Why were they buried in that stone kist, in a sand dune? Why were they left there and never collected? - I so much want to know, and I never shall. There's a story there, somewhere. I wish somebody would write it.

For more information, go to http://en.wikipedia.org

/wiki/Lewis_chessmen

Or here - http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/LcdERPxmQ_a2npYstOwVkA

Published on July 25, 2014 16:05

July 18, 2014

Barra

It was in May, a Monday afternoon, full of dull work, and an expectation of nothing more for the rest of the week. About 3pm, the phone rang. It was Davy, my partner. He said, 'Have your bag by the door for 6am, we're going to the Outer Hebrides.'

I was, as old stories used to say, nothing loathe. I started chucking knickers and socks into a bag.

The phone rang again. 'Bag by the door at 3-30 am.'

The full story was that Davy's brother was doing supply teaching on the Isle of Barra, in the secondary school where the entire pupil-roll numbered 94. (The entire population is only 1,174.)

The brother had a little rented cottage, its spare bedroom currently empty, and we were invited - but we had to be quick off the mark because end of term was coming up, and the brother didn't know for sure how much longer he was going to be there.

The early start was a necessity because of the ferries. We had to catch the 1pm Cally-Mac from Oban, because there wouldn't be

386 milesanother until the evening of the day after.

386 milesanother until the evening of the day after.So off we went, in the wee small hours. Davy drove for eight hours. We stopped briefly at Carlisle, for petrol - but the cafe where we usually have a drink on the way to Scotland wasn't even open at 6am. We made it to Oban by around 11-30am, and booked ourselves on the ferry.

I love Oban, with its view out to Kerrara and Mull, and the other Hebrides - but we didn't see much of it apart from the harbour and the ferry complex this time.

Kerrara (in foreground) and Mull, from Oban

Kerrara (in foreground) and Mull, from ObanIt took seven hours on the ferry to sail from Oban, past the island of Mull, and then to the Outer Hebrides. We were taking a roundabout route - the ferry calls, on Tuesdays, at Lochboisdale in South Uist, before going on to Castlebay on Barra. The more direct route takes only five hours.

Route from Oban to Castlebay, Barra. The island of Barra marked with red spot.

Route from Oban to Castlebay, Barra. The island of Barra marked with red spot.We got into Castlebay - so called because there's a castle in the bay - at about 8pm, and were met by brother Jim, who led us around the island to the quiet little inlet where his cottage was.

Davy taking photos on Barra. The only other person on this beach was me.

Davy taking photos on Barra. The only other person on this beach was me. Well, except for this fella, the beach's only other occupant. Had a pebble. Kept bringing it to be thrown.

Well, except for this fella, the beach's only other occupant. Had a pebble. Kept bringing it to be thrown. The sunny day.

The sunny day.We had a couple of sunny days, and they were glorious, with blue skies, seas of duck-egg blue and turquoise, and white beaches. I've never seen so many primroses, growing along roadside verges and across whole banks - it made me think of Shakespeare's 'primrose-path.' There were also many of the tiniest little dots of lambs I've ever seen, but they bounced and scarpered off into the landscape, with waving tails, before I could get a good photograph.

The island is Roman Catholic, and tourists are told that it's named after St. Barr - yet there don't seem to be any legends about the Saint, or any explanation of what he was doing there. In fact, the island's name is a mixture of Gaelic and Norse - the Gaelic 'barro' meaning 'hill,' and the Norse 'ey' meaning 'island.' - 'Hilly island' - a fair enough description. [Room, 1988.]

Why the only town is called 'Castlebay.' The only town on the island is called by the oddly English name of Castlebay, and this is why - Kisimull Castle, out in the middle of the bay. (The name means 'Castle Island.') The castle, and the island of Barra, were the stronghold of Clan MacNeil, and donations came in from MacNeils all around the world, to rebuild the castle when it was gutted by fire. The MacNeils suffered terribly in the 19th Century, the age of the Clearances, partly because their Protestant, absentee landlords felt justified in having their bailiffs burn them out of their crofts and leaving them to starve. At its southern end, Barra is linked by a causeway to the island of Vatersay, just as beautiful as Barra, but much less hilly. Davy was taking photographs like mad, and has completed two paintings based on them since we came back. I could see him falling in love with the place, so I'm pretty sure we'll be sailing into Castlebay again.

Why the only town is called 'Castlebay.' The only town on the island is called by the oddly English name of Castlebay, and this is why - Kisimull Castle, out in the middle of the bay. (The name means 'Castle Island.') The castle, and the island of Barra, were the stronghold of Clan MacNeil, and donations came in from MacNeils all around the world, to rebuild the castle when it was gutted by fire. The MacNeils suffered terribly in the 19th Century, the age of the Clearances, partly because their Protestant, absentee landlords felt justified in having their bailiffs burn them out of their crofts and leaving them to starve. At its southern end, Barra is linked by a causeway to the island of Vatersay, just as beautiful as Barra, but much less hilly. Davy was taking photographs like mad, and has completed two paintings based on them since we came back. I could see him falling in love with the place, so I'm pretty sure we'll be sailing into Castlebay again. Vatersay

Vatersay Davy leaving Vatersay beach for a primrose path.

Davy leaving Vatersay beach for a primrose path.

Published on July 18, 2014 16:05

July 11, 2014

Convert to Mrs Brown

I gather that some very harsh and snooty things have been

Brenden O'Carroll as Mrs. Brown...said about Brenden O'Carroll's comedy, Mrs. Brown's Boys.

Brenden O'Carroll as Mrs. Brown...said about Brenden O'Carroll's comedy, Mrs. Brown's Boys.

Grace Dent of The Independent, a woman whose views I usually find sound (that is, she agrees with me), said, '...To love Mrs Brown, one must be thrilled by a man in a hairnet and dinner lady tabard saying the F-word roughly once every ten minutes...' Paul English, in The Daily Record, called it, '...lazy, end-of-pier trash rooted in the 1970s...' and said that it made him angry to see the BBC dropping standards so far. Even The Irish Independent said that it made them embarrassed to be Irish. Ouch.

I usually give any new comedy a look, but I passed on Mrs. Brown when it was first shown in England - mostly because Mrs. Brown was played by a man in a dress and I had traumatic memories of Dick Emery. I couldn't stand the man.

Then I read a blog in the Guardian, which I can't find now, or I'd link to it. It said that Mrs. Brown's Boys was an odd mixture of old-fashioned and new - that it played more daring tricks with breaking 'the fourth wall' than almost anything else on TV, and was far better than the critics admitted. So I thought I'd give it a go after all.

...and as himself. And I'm a convert to Mrs. Brown. It regularly makes me laugh out loud when I'm sitting by myself.

...and as himself. And I'm a convert to Mrs. Brown. It regularly makes me laugh out loud when I'm sitting by myself.

Yes, what we have to call 'the F-word' flies around freely, but I don't care about that. I use it pretty frequently myself. (It's obviously news to some critics that women can and do eff and blind.) What I like about the programme is that it's bloody funny.

Something that immediately struck me when I first watched it is, that if I hadn't already known Mrs. Brown was played by a man, I wouldn't have realised it - because Brenden O'Carroll makes an entirely convincing elderly woman. Indeed, I was recently talking with a (male) friend who had seen a couple of episodes, and I had a hard time convincing him that Mrs. Brown was, in fact, played by a man. He kept saying, 'Are you sure? Are you sure it's not an actress?'

O'Carroll's Mrs. Brown is not a 1970s caricature of femininity, with an large dollop of 1970s contempt and dislike. Mrs. Brown smokes, drinks, speaks in a throaty voice, and swears a lot - but any critic who hasn't known an elderly woman like that has led a very sheltered life. The character is said to be based on O'Carroll's own mother, a working class Labour Party TD, of whom he seems to be proud, and with good reason. O'Carroll plays her as larger than life, but she's the engine of the plot, not the butt of the jokes. She is nosy, bossy, managing - but also sharp, shrewd, knowing, loving and intelligent.

There was a touching moment when, anxious about one of her grown children, Mrs. Brown turned to the camera and said, "Oh, that's what it's like being a mother. No matter how old they grow, you never stop worrying about them." The live audience all went, "Aaaah." Whereupon Mrs. Brown glared at them and, indicating herself with a sweep of her hands, snapped, "It's a man in a f***k*** frock!" I fell about.

The set is, at once, a realistic small house and an obvious set, where the actors and camera interact to play jokes. The phone in the living-room keeps ringing and cutting off before Mrs. Brown can reach it. So she sidles in and out of the door between the kitchen and living room, daring it to ring and trying to catch it out.

The camera, trying to stay on her, swings between the two rooms, passing 'through' the dividing wall each time. But like two people trying to dodge each other in a doorway and always getting in each other's way, Mrs. Brown always manages to be on the other side of the wall from the camera. She and it play hide-and-seek for several seconds.

If we had simply watched her bobbing in and out of the doorway, daring the phone to ring, it would have been funny - we've all done something like that. But the surrealism of the camera passing through a wall and never being able to catch her, adds another dimension of comedy.

In another instance, Mrs. Brown has gone to the pub, but discovers that she's left her handbag at home. So she jumps up and - followed by the camera - runs across the sets, jumping cables and saying hello to sound-men - to fetch her handbag.

In every episode, Mrs. Brown addresses the audience directly several times, as if we were other visitors to her kitchen. The other actors, too - many of whom are O'Carroll's family - will suddenly drop out of character and make comments on each other's lives, or earlier filming mistakes. They frequently corpse, and when they do, the rest of the cast will mercilessly draw attention to the fact.

So it's both a TV sit-com, and a stage performance - and also an obvious, admitted pretence. The actors are both the characters they're playing and themselves. And - did I mention? - it's also bloody funny.

And that 'man in drag' matter again. Why, some superior critic asked, do women of a certain age find a man dressed up as a woman so funny? - The question asked with the clear implication that they showed a sad lack of taste by doing so.

Well, here's my take on it. Women, especially younger women, are required to pretend they're something they're not for most of their lives. They're supposed to be slim, and dainty, so they deny themselves and diet. They're supposed to be hairless, except on their heads, so they shave and wax. They're not supposed to get old, so they use make-up and wrinkle-creams and dye their hair. Drinking, smoking and swearing are all supposed to be 'un-ladylike', even today, or there wouldn't be so much tabloid hoopla about it. After all, drunken men have been fighting and urinating in the streets since there were streets, but the Mail and Telegraph rarely make much of fuss about it.

But the 'man in drag' act - especially when the woman portrayed is like Agnes Brown - admits a great truth. Woman are much the same as men. We're just as clumsy, graceless and stolid. Many of us are overweight. We are, naturally, almost as hairy. We drink and burp, and smoke and swear. We make filthy jokes and think filthy thoughts. Not every dear old granny smells of baking and lilac, or wants to.

Part of the laughter, I think, is a celebration of this simple truth, a great outbreak of relief.

And then, again - the old ones are best. What's wrong with an old joke? It made my grandparents laugh in the music-hall - it makes me laugh now.

Mrs Brown's Boys = Bloody Funny.

Brenden O'Carroll as Mrs. Brown...said about Brenden O'Carroll's comedy, Mrs. Brown's Boys.

Brenden O'Carroll as Mrs. Brown...said about Brenden O'Carroll's comedy, Mrs. Brown's Boys.Grace Dent of The Independent, a woman whose views I usually find sound (that is, she agrees with me), said, '...To love Mrs Brown, one must be thrilled by a man in a hairnet and dinner lady tabard saying the F-word roughly once every ten minutes...' Paul English, in The Daily Record, called it, '...lazy, end-of-pier trash rooted in the 1970s...' and said that it made him angry to see the BBC dropping standards so far. Even The Irish Independent said that it made them embarrassed to be Irish. Ouch.

I usually give any new comedy a look, but I passed on Mrs. Brown when it was first shown in England - mostly because Mrs. Brown was played by a man in a dress and I had traumatic memories of Dick Emery. I couldn't stand the man.

Then I read a blog in the Guardian, which I can't find now, or I'd link to it. It said that Mrs. Brown's Boys was an odd mixture of old-fashioned and new - that it played more daring tricks with breaking 'the fourth wall' than almost anything else on TV, and was far better than the critics admitted. So I thought I'd give it a go after all.

...and as himself. And I'm a convert to Mrs. Brown. It regularly makes me laugh out loud when I'm sitting by myself.

...and as himself. And I'm a convert to Mrs. Brown. It regularly makes me laugh out loud when I'm sitting by myself.Yes, what we have to call 'the F-word' flies around freely, but I don't care about that. I use it pretty frequently myself. (It's obviously news to some critics that women can and do eff and blind.) What I like about the programme is that it's bloody funny.

Something that immediately struck me when I first watched it is, that if I hadn't already known Mrs. Brown was played by a man, I wouldn't have realised it - because Brenden O'Carroll makes an entirely convincing elderly woman. Indeed, I was recently talking with a (male) friend who had seen a couple of episodes, and I had a hard time convincing him that Mrs. Brown was, in fact, played by a man. He kept saying, 'Are you sure? Are you sure it's not an actress?'

O'Carroll's Mrs. Brown is not a 1970s caricature of femininity, with an large dollop of 1970s contempt and dislike. Mrs. Brown smokes, drinks, speaks in a throaty voice, and swears a lot - but any critic who hasn't known an elderly woman like that has led a very sheltered life. The character is said to be based on O'Carroll's own mother, a working class Labour Party TD, of whom he seems to be proud, and with good reason. O'Carroll plays her as larger than life, but she's the engine of the plot, not the butt of the jokes. She is nosy, bossy, managing - but also sharp, shrewd, knowing, loving and intelligent.

There was a touching moment when, anxious about one of her grown children, Mrs. Brown turned to the camera and said, "Oh, that's what it's like being a mother. No matter how old they grow, you never stop worrying about them." The live audience all went, "Aaaah." Whereupon Mrs. Brown glared at them and, indicating herself with a sweep of her hands, snapped, "It's a man in a f***k*** frock!" I fell about.

The set is, at once, a realistic small house and an obvious set, where the actors and camera interact to play jokes. The phone in the living-room keeps ringing and cutting off before Mrs. Brown can reach it. So she sidles in and out of the door between the kitchen and living room, daring it to ring and trying to catch it out.

The camera, trying to stay on her, swings between the two rooms, passing 'through' the dividing wall each time. But like two people trying to dodge each other in a doorway and always getting in each other's way, Mrs. Brown always manages to be on the other side of the wall from the camera. She and it play hide-and-seek for several seconds.

If we had simply watched her bobbing in and out of the doorway, daring the phone to ring, it would have been funny - we've all done something like that. But the surrealism of the camera passing through a wall and never being able to catch her, adds another dimension of comedy.

In another instance, Mrs. Brown has gone to the pub, but discovers that she's left her handbag at home. So she jumps up and - followed by the camera - runs across the sets, jumping cables and saying hello to sound-men - to fetch her handbag.

In every episode, Mrs. Brown addresses the audience directly several times, as if we were other visitors to her kitchen. The other actors, too - many of whom are O'Carroll's family - will suddenly drop out of character and make comments on each other's lives, or earlier filming mistakes. They frequently corpse, and when they do, the rest of the cast will mercilessly draw attention to the fact.

So it's both a TV sit-com, and a stage performance - and also an obvious, admitted pretence. The actors are both the characters they're playing and themselves. And - did I mention? - it's also bloody funny.

And that 'man in drag' matter again. Why, some superior critic asked, do women of a certain age find a man dressed up as a woman so funny? - The question asked with the clear implication that they showed a sad lack of taste by doing so.

Well, here's my take on it. Women, especially younger women, are required to pretend they're something they're not for most of their lives. They're supposed to be slim, and dainty, so they deny themselves and diet. They're supposed to be hairless, except on their heads, so they shave and wax. They're not supposed to get old, so they use make-up and wrinkle-creams and dye their hair. Drinking, smoking and swearing are all supposed to be 'un-ladylike', even today, or there wouldn't be so much tabloid hoopla about it. After all, drunken men have been fighting and urinating in the streets since there were streets, but the Mail and Telegraph rarely make much of fuss about it.

But the 'man in drag' act - especially when the woman portrayed is like Agnes Brown - admits a great truth. Woman are much the same as men. We're just as clumsy, graceless and stolid. Many of us are overweight. We are, naturally, almost as hairy. We drink and burp, and smoke and swear. We make filthy jokes and think filthy thoughts. Not every dear old granny smells of baking and lilac, or wants to.

Part of the laughter, I think, is a celebration of this simple truth, a great outbreak of relief.

And then, again - the old ones are best. What's wrong with an old joke? It made my grandparents laugh in the music-hall - it makes me laugh now.

Mrs Brown's Boys = Bloody Funny.

Published on July 11, 2014 16:05

July 4, 2014

I'm Back...

Where were we?

I see that it was February when I closed this blog because I just couldn't keep up with things.

The major reason for that was the training course I was taking with the Royal Literary Fund (RLF) to be an accredited RLF Writing Consultant.

Which I now am - pause for parade, flags, brass-band, 21-gun salute and RAF fly-by - but it was hard. At the recent celebratory weekend, all the brand new consultants agreed on that. But then, I suppose, it should have been.

The RLF has, for over ten years now, been placing professional writers in universities all over the UK, with their Writing Fellowship scheme. The writers are paid, by the RLF, to be on campus two days a week, and to provide one-to-one, free advice on writing to any student who comes along.

The RLF has, for over ten years now, been placing professional writers in universities all over the UK, with their Writing Fellowship scheme. The writers are paid, by the RLF, to be on campus two days a week, and to provide one-to-one, free advice on writing to any student who comes along.

The scheme has been a great success, and I thoroughly enjoyed my three years as an RLF Writing Fellow.

The RLF decided to build on the success of the Fellowships, and see if they could train some of their ex-Fellows to be consultants who would go into universities, colleges and schools, and give workshops on such things as Academic Writing, essay structure, basic writing skills (something which many university students badly need) and many other things.

I signed up for the training for two reasons - one, my experience as a Fellow showed me that although I knew a lot about writing, I knew very little about teaching - and two, I was interested in joining forces with my cousin on his Stories4Learning reading strategy, and to do that I also needed to know more about teaching.

The consultancy training course was a prototype, to see how well it would work, and how it could be improved. We were asked for feedback at the celebratory weekend, and one of the questions was: What would you like future trainees to know about the course?

I would say: Don't, whatever you do, think it is going to be a stroll!

I made that mistake. Well, it wasn't that I thought it would be easy, exactly... I suppose I've got used to picking up things on the fly. As a writer I've done that most of my life. Talk to someone about AK4s for half an hour, and you can give the impression, in a book, that you know an awful lot about armaments. In fact, you picked up just enough to give that impression.

But the RLF course was a teacher-training course in miniature. I had to pay attention. For hours at a time. And to things I wasn't really that interested in. I'm not good at any of this. My style is more: work concentratedly for 10-15 minutes, go and do something else, come back and work for another 15 minutes, wander off and do something else... and so on, into the small hours of the morning quite often.

The course was broken up into three parts. First, over a weekend at Aston University in Birmingham, we were bombarded with stuff about teaching styles, university organisation, how to arrange classrooms, the psychology of learning... We each had to do a ten minute 'presentation' before a bunch of students who'd been bribed by the RLF with vouchers. Later, we got feedback from the mentors and trainers. Always a joy.

Then, early this year, the whole shebang moved to London. First came a training day in a Royal Plaza Hotel. Here we had to do another ten minutes solo presentation to the trainers, mentors, and other trainees. More feedback, and more lectures.

The following day, we moved out to London University, where we had to team up with another trainee and do a joint presentation to another group of students, bribed with more vouchers and free lunch. More feedback. (To be fair, I have to say that my mentors, Katherine Grant, and Max Adams, couldn't have been kinder, more positive and helpful if they'd gone into training for it.)

Next came the work-experience section of the training. We each had to plan a three-hour workshop - which could be a single three-hour session, or broken down into shorter sessions. This had to be hosted by a university or school, but the RLF paid our fee and expenses. I did two sessions, of two hours and one hour, at an RSA Academy.

While planning this workshop, we had to keep a journal, and write a 'reflective essay' on the experience - why we chose to do what we did, what we'd learned, how our attitudes had changed, and so on. The essay had to have at least 6-8 academic citations and a reference list.

The workshop(s) were observed by an RLF observer, who gave feedback later - and the 'client' and the students also had to fill out feedback forms.

It was hard. But I passed.

I've been 'giving talks' for forty years, and I've become rather good at it. But this course made it very clear to me that there is a huge difference between putting together an hour or 45 minutes intended to entertain - which is essentially what I was doing - and constructing a 'workshop' of the same length which is intended to teach something.

I have never been one to think that teachers have a cushy job - I've seen too many of them at work, and known too many of them ploughing their way through marking and timetabling to think that. Despite appreciating that it was a hard job, though, this course has increased my respect for the teaching profession hugely.

As for the RLF - I don't know that anything could increase the respect I have for this amazing organisation. With typical generosity, they not only came up with this opportunity, but paid us for our 'work-experience', paid all our travel and accommodation, and put us up in very nice hotels. And gave us gifts - I got a gift voucher for taking part, and another for passing.

For last weeks 'celebratory weekend,' they put 20 of us up in the Royal Plaza Hotel, Westminster Bridge, hired a fifteenth floor suite for the meeting, and held a champagne reception for us on the terrace overlooking Waterloo Bridge. Then they took us all out for Italian.

They have set up a new website featuring their new consultants, and will be launching it at an educational conference next week.

It was a blessed day, I think, that I first heard of the Royal Literary Fund - even if I am a republican.

I see that it was February when I closed this blog because I just couldn't keep up with things.

The major reason for that was the training course I was taking with the Royal Literary Fund (RLF) to be an accredited RLF Writing Consultant.

Which I now am - pause for parade, flags, brass-band, 21-gun salute and RAF fly-by - but it was hard. At the recent celebratory weekend, all the brand new consultants agreed on that. But then, I suppose, it should have been.

The RLF has, for over ten years now, been placing professional writers in universities all over the UK, with their Writing Fellowship scheme. The writers are paid, by the RLF, to be on campus two days a week, and to provide one-to-one, free advice on writing to any student who comes along.

The RLF has, for over ten years now, been placing professional writers in universities all over the UK, with their Writing Fellowship scheme. The writers are paid, by the RLF, to be on campus two days a week, and to provide one-to-one, free advice on writing to any student who comes along.The scheme has been a great success, and I thoroughly enjoyed my three years as an RLF Writing Fellow.

The RLF decided to build on the success of the Fellowships, and see if they could train some of their ex-Fellows to be consultants who would go into universities, colleges and schools, and give workshops on such things as Academic Writing, essay structure, basic writing skills (something which many university students badly need) and many other things.

I signed up for the training for two reasons - one, my experience as a Fellow showed me that although I knew a lot about writing, I knew very little about teaching - and two, I was interested in joining forces with my cousin on his Stories4Learning reading strategy, and to do that I also needed to know more about teaching.

The consultancy training course was a prototype, to see how well it would work, and how it could be improved. We were asked for feedback at the celebratory weekend, and one of the questions was: What would you like future trainees to know about the course?

I would say: Don't, whatever you do, think it is going to be a stroll!

I made that mistake. Well, it wasn't that I thought it would be easy, exactly... I suppose I've got used to picking up things on the fly. As a writer I've done that most of my life. Talk to someone about AK4s for half an hour, and you can give the impression, in a book, that you know an awful lot about armaments. In fact, you picked up just enough to give that impression.

But the RLF course was a teacher-training course in miniature. I had to pay attention. For hours at a time. And to things I wasn't really that interested in. I'm not good at any of this. My style is more: work concentratedly for 10-15 minutes, go and do something else, come back and work for another 15 minutes, wander off and do something else... and so on, into the small hours of the morning quite often.

The course was broken up into three parts. First, over a weekend at Aston University in Birmingham, we were bombarded with stuff about teaching styles, university organisation, how to arrange classrooms, the psychology of learning... We each had to do a ten minute 'presentation' before a bunch of students who'd been bribed by the RLF with vouchers. Later, we got feedback from the mentors and trainers. Always a joy.

Then, early this year, the whole shebang moved to London. First came a training day in a Royal Plaza Hotel. Here we had to do another ten minutes solo presentation to the trainers, mentors, and other trainees. More feedback, and more lectures.

The following day, we moved out to London University, where we had to team up with another trainee and do a joint presentation to another group of students, bribed with more vouchers and free lunch. More feedback. (To be fair, I have to say that my mentors, Katherine Grant, and Max Adams, couldn't have been kinder, more positive and helpful if they'd gone into training for it.)

Next came the work-experience section of the training. We each had to plan a three-hour workshop - which could be a single three-hour session, or broken down into shorter sessions. This had to be hosted by a university or school, but the RLF paid our fee and expenses. I did two sessions, of two hours and one hour, at an RSA Academy.

While planning this workshop, we had to keep a journal, and write a 'reflective essay' on the experience - why we chose to do what we did, what we'd learned, how our attitudes had changed, and so on. The essay had to have at least 6-8 academic citations and a reference list.

The workshop(s) were observed by an RLF observer, who gave feedback later - and the 'client' and the students also had to fill out feedback forms.

It was hard. But I passed.

I've been 'giving talks' for forty years, and I've become rather good at it. But this course made it very clear to me that there is a huge difference between putting together an hour or 45 minutes intended to entertain - which is essentially what I was doing - and constructing a 'workshop' of the same length which is intended to teach something.

I have never been one to think that teachers have a cushy job - I've seen too many of them at work, and known too many of them ploughing their way through marking and timetabling to think that. Despite appreciating that it was a hard job, though, this course has increased my respect for the teaching profession hugely.

As for the RLF - I don't know that anything could increase the respect I have for this amazing organisation. With typical generosity, they not only came up with this opportunity, but paid us for our 'work-experience', paid all our travel and accommodation, and put us up in very nice hotels. And gave us gifts - I got a gift voucher for taking part, and another for passing.

For last weeks 'celebratory weekend,' they put 20 of us up in the Royal Plaza Hotel, Westminster Bridge, hired a fifteenth floor suite for the meeting, and held a champagne reception for us on the terrace overlooking Waterloo Bridge. Then they took us all out for Italian.

They have set up a new website featuring their new consultants, and will be launching it at an educational conference next week.

It was a blessed day, I think, that I first heard of the Royal Literary Fund - even if I am a republican.

Published on July 04, 2014 16:05

February 15, 2014

I'...

I'm afraid I have to declare this blog closed until further notice.

I have such a press of work on, for the RLF, schools and so forth, that I'm having to be very strict about time.

To everyone who was kind enough to read this - have a great spring!

Published on February 15, 2014 16:00

February 7, 2014

If You Want To Know The Time...

If you want to know the time, ask a policeman.

The proper Greenwich time, ask a policeman,

Every member of the force has a watch and chain, of course,If you want to know the time, ask a policeman!

My childhood was haunted by snatches of music-hall song and jokes. My Grandfather Price, I'm told, was a great fan of the music-hall, especially the high-kicking dancing girls. (And I heard, passed down from him, tales of the dreaded 'peaky-blinders' long before they became a TV series.)

They don't do repairs in mid-ocean.They don't do repairs on the deck.So for two blessed years, me trousers was hungFrom a wart on the back of me neck!- boom-boom!

To this day, I've no idea what this is about. I didn't understand these half-remembered bits of verse. As with nursery rhymes, I learned them by their rythmns, without knowing or much caring what they meant.She looked at me coy,She said, 'You're not a boy.Get off! You're a dirty old man!' - boom-boom!

That star of children's TV, the puppet fox, Basil Brush, used to end all his jokes with 'boom-boom!' too. But long before Basil came along, I knew that was how you ended a joke. I asked my Dad why, and he said it was because, in music-hall, there was a live orchestra in the pit, and at the end of every punch-line, the drummer would give two thumps on the bass-drum. Later, the comics added it themselves.

I'm one of the ruins that Cromwell knocked about a bit... (Often said in reference to Dudley castle.)

My old man said 'Follow the van...'

'You don't know Nellie like I do,' said the bird on Nellie's hat...

'Here's a joke worth eighteenpence...'

'On the day I was born, my father threw a party in the yard.

The party was my mother.

'My parents were in the iron and steel business.

My mother ironed and my father did the stealing.'

'My father died as he was addressing a public meeting.

The platform collapsed and he broke his neck.'

But I was talking about 'Ask A Policeman.' The only bit of this song I learned as a child was the chorus quoted at the top of this blog. I had a vague idea that it was a song in praise of fine, upstanding British Bobbies, who would always greet you with a smile and give you the time of day. I once asked my Dad (that fount of all knowledge) about it, and he more or less confirmed this. Perhaps he was protecting me from the hard and cynical world, but I have the impression that he'd never given much thought to the song himself (he was more of a Duke Ellington man.) My researches reveal that 'Ask a Policeman' was written by Augustus Durandeau (music) and E. W Rogers (lyrics,) and first performed by James Fawn in the 1890s. The first verse and chorus go: The police force is a noble band, that safely guard our streets.Their valor is unquestion'd, and they're noted for their 'feats,'If anything you wish to know, they'll tell you with a grin,In fact, each one of them is a complete "Enquire Within."

Chorus.If you want to know the time, ask a policeman.The proper Greenwich time, ask a policeman,Every member of the force has a watch and chain, of course,If you want to know the time, ask a policeman.

But that idea that the song is one of love for our cheery, helpful policemen? Those last lines from the chorus - 'Every member of the force has a watch and chain, of course,' - was sung with a knowing nod and wink to the audience. It was a reference to a well-know urban tale of the time. Everybody knew that when policemen - who were usually working class - came across a well oiled gentleman, the policemen not only gleefully took advantage of their office to arrest the gentleman for being 'drunk and disorderly' when he was only a little high-spirited, but also stole the gentleman's pocket-watch.

A gentleman's expensive pocket-watch, a little miracle of clockwork engineering, accurately counting off the seconds and minutes, was the coveted gadget, the iPad of its day. A police constable couldn't afford one. Yet they always had one! - Because they stole them from their betters. I suppose there's never been a time when the Police Force has been surrounded by the warm glow of love and approval from the public it serves - despite the necessity of having some such institution. But when the Force first came into being, it was hated not only by the criminal classes (both rich and poor), but by everyone. And especially by those who considered themselves respectable and rather above the common herd. The Police were, in the main, lower-class men, granted the power to enter the houses of their betters, to ask impertinently about their whereabouts on the night in question, and even to arrest them on suspicion of crimes. Before the establishment of the Force, justice had been in the hands of the local gentry, as was proper. Fellow gentlefolk could be counted on to understand the difficulties a gentleman might find himself in. And so arose the story of the thieving policeman who - instead of arresting real criminals - targeted the squiffy toff, just so he could pinch his watch. And what if the toff had smashed a few shop-keepers' windows, or broken some street-lamps? - It was only high-spirits, and outrageous to call it 'criminal damage' as if it had been done by some rowdy costermonger or navvy.

A gentleman's expensive pocket-watch, a little miracle of clockwork engineering, accurately counting off the seconds and minutes, was the coveted gadget, the iPad of its day. A police constable couldn't afford one. Yet they always had one! - Because they stole them from their betters. I suppose there's never been a time when the Police Force has been surrounded by the warm glow of love and approval from the public it serves - despite the necessity of having some such institution. But when the Force first came into being, it was hated not only by the criminal classes (both rich and poor), but by everyone. And especially by those who considered themselves respectable and rather above the common herd. The Police were, in the main, lower-class men, granted the power to enter the houses of their betters, to ask impertinently about their whereabouts on the night in question, and even to arrest them on suspicion of crimes. Before the establishment of the Force, justice had been in the hands of the local gentry, as was proper. Fellow gentlefolk could be counted on to understand the difficulties a gentleman might find himself in. And so arose the story of the thieving policeman who - instead of arresting real criminals - targeted the squiffy toff, just so he could pinch his watch. And what if the toff had smashed a few shop-keepers' windows, or broken some street-lamps? - It was only high-spirits, and outrageous to call it 'criminal damage' as if it had been done by some rowdy costermonger or navvy. If you stay out late at night and pass through regions queer

Thanks to those noble guardians of foes you have no fear.

If drink you want and 'pubs' are shut go to the man in blue,

Say you're thirsty and good-natured, and he'll show you what to do.

Chorus.If you want to get a drink, ask a p'liceman.

He'll manage it I think, will a p'liceman.

He'll produce the flowing pot, if the 'pubs' are shut or not,

He could open all the lot, ask a p'liceman.

If your servant suddenly should leave her cosy place,

Don't get out an advertisement her whereabouts to trace.

You're told it was a soldier who removed her box of clothes -

Don't take the information in, but ask the man who knows.

Chorus.If you don't know where she is, ask a p'liceman

Chorus.If you don't know where she is, ask a p'licemanFor he's 'in the know' he is, ask a p'liceman.

Though they say with 'red ' she flew yet its ten to one on 'blue,'

For he mashes just a few. Ask a p'liceman.

Who guards the guardians? Those set to prevent you buying drink at certain hours, will also see there's a profit to be made in supplying it. And another persistent tale about the early policemen was that they spent most of their time, when they were supposed to be on duty, sitting in some comfortably-off man's kitchen, eating his food and flirting with his cook and maids.

Given that there is so much unspoken meaning behind the words, I'm puzzled to guess how much should be read into the verse about the maid. The master's concern to trace the missing maid could be nothing more than kindly concern - but would the original audience have heard more than that? And why has the policeman lured her away? 'A Masher' was the current term for a strutting young man, but here it seems to have a more sexual meaning. Are we meant to understand that the servant ran away because she was pregnant by the policeman? - Or ran away to live with him? Is there even a hint that police-officers were involved in prostitution? Or am I reading altogether too much into it?

The Policeman's villainy comes even nearer home in the next verse:-

Or if you're called away from home, and leave your wife behind

You say, 'Oh would that I a friend to guard the house could find,

And keep my love in safety,' - but let your troubles cease!

You'll find the longed-for keeper in a member of the p'lice.

Chorus: If your wife should want a friend, ask a p'liceman,

Who a watchful eye will lend, ask a p'liceman

Truth and honour you can trace, written on his manly face -

When you're gone he'll mind your place, ask a p'liceman.

My favourite verse is the last. I enjoy the neatness of the rhyming. It also reminds us that an obsession with losing weight is not such a modern thing as we think.

And if you're getting very stout your friends say in a trice

'Consult a good physician, and he'll give you this advice:

Go in for running all you can no matter when or how

And if you'll have a trainer, watch a bobby in a row.

Chorus.If you want to learn to run, ask a p'liceman.

How to fly, though twenty 'stun', ask a p'liceman.

Watch a bobby in a fight - in a tick he's out of sight!

For advice on rapid flight, ask a p'liceman.

So, in addition to being a thief, a seller of illicit drink, a lurer away of servant girls and a seducer of wives, that nasty lower-class plod is a coward too!

That was 1890. By 1919, Marie Lloyd was singing,

"But you can't trust a special like an old time copperWhen you can't find your way 'ome!"

Thirty years had passed. The Police Force had become an accepted fact of life - and it was the new idea of 'specials' that was attracting suspicion.

Dillying and dallying A special vote of thanks to my brother, Andrew, who went above and beyond in tracking down the definitive lyrics of 'Ask A Polliceman,' when I had given up and was prepared to leave blanks where I didn't know the lines, in the verses about the maid and the wife. He also supplied the illustration at the top of the blog.

Dillying and dallying A special vote of thanks to my brother, Andrew, who went above and beyond in tracking down the definitive lyrics of 'Ask A Polliceman,' when I had given up and was prepared to leave blanks where I didn't know the lines, in the verses about the maid and the wife. He also supplied the illustration at the top of the blog.Also, I won't be able to respond to comments promptly, as I shall be away over the weekend, on a Royal Literary Fund training course.

Published on February 07, 2014 16:05

January 24, 2014

A Ladder to Reading

A double-whammy this week, as my usual Saturday blog

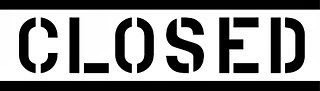

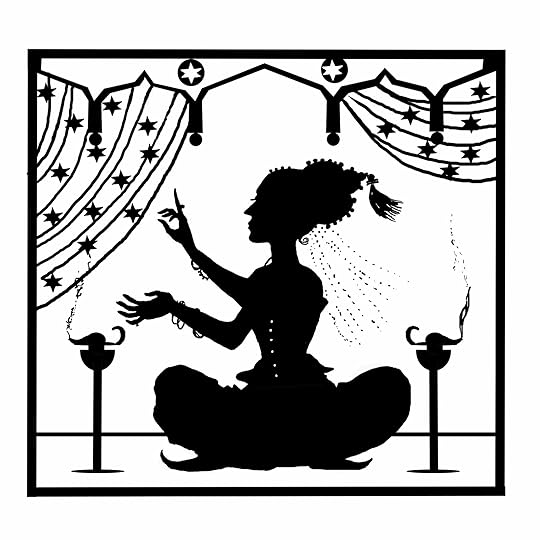

Scherezade telling stories for learning: Art work copyright Andrew Pricecoincides with my posting day over at Do Authors Dream of Electric Books - the 25th of the month.

Scherezade telling stories for learning: Art work copyright Andrew Pricecoincides with my posting day over at Do Authors Dream of Electric Books - the 25th of the month.

So, over there I'm posting about the reading scheme, Stories4Learning.

Below I post an interview with Dr David Rose, who set out to help the children routinely dismissed as 'not academic' - the children who reach Secondary School with poor literacy skills. Their education more or less comes to a halt, and their opportunities in life become very limited.

As Dr Rose puts it, 'In primary school you learn to read. In secondary school, (and after) you read to learn.'

Much of the groundwork for learning to read is actually laid before a child ever gets near a school. If a child is talked to by its family and told stories, if it's shown picture books and read stories - then that child will begin school with a larger vocabulary, a greater ability to listen to and understand instructions, a familiarity with books and stories.

This gives them a huge advantage over a child who isn't talked to as much, who isn't read or told stories.

And that's without even considering the children who speak a different language at home, but are taught in English.

If, because of this early handicap, you are slower to read than others in your class, that's humiliating. You may retreat from this and protect yourself by taking the stance that reading is 'stupid', or that you are not clever enough, and so might as well not bother.

If you find reading so slow and difficult that most of your energy is spent in simply figuring out what the signs on the page are, rather than understanding the information they convey, then reading is going to seem, even more, a pointless and frustrating activity, which you avoid whenever possible.

How much you will then miss! - Not only simple information, and entertainment, but insight into the motivations and emotions of others.

But I'll shut up, and let Dr. Rose speak for himself. (The video is about 8 minutes long.)

One of the great advantages of this form of learning languages - whether written or spoken, your own or a foreign language - is that it can be used for any age-group, at any level.

It also simultaneously teaches a subject and improves reading. For instance, if the subject you're teaching is geography, you take a short text from the geography lesson, and go through the stages of examining the text in detail, taking it apart and reconstructing it. The students not only improve their reading ability - they end by knowing the content of the text better too.

The text you use in class could just as well be about football, or ponies, or whatever else will interest the students.

Dr Rose has data from many schools, which demonstrate that the more able students continue to improve - but the 'less academic' students improve more, and improve faster. The method 'ladders' the weaker students up to a more equal standing with the best students.

Here, some of the teachers who use the Reading To Learn method in New South Wales, talk about it. (This video is about 3 minutes.)

Follow this link to the Authors Electric blog, and you can read about the Stories4Learning site, which I am developing with Alan Hess, a special needs teacher who lives and works in Switzerland.

And fare thee well...

Puss in Boots bows out - Artwork copyright Andrew Price

Puss in Boots bows out - Artwork copyright Andrew Price

Scherezade telling stories for learning: Art work copyright Andrew Pricecoincides with my posting day over at Do Authors Dream of Electric Books - the 25th of the month.

Scherezade telling stories for learning: Art work copyright Andrew Pricecoincides with my posting day over at Do Authors Dream of Electric Books - the 25th of the month.So, over there I'm posting about the reading scheme, Stories4Learning.

Below I post an interview with Dr David Rose, who set out to help the children routinely dismissed as 'not academic' - the children who reach Secondary School with poor literacy skills. Their education more or less comes to a halt, and their opportunities in life become very limited.

As Dr Rose puts it, 'In primary school you learn to read. In secondary school, (and after) you read to learn.'

Much of the groundwork for learning to read is actually laid before a child ever gets near a school. If a child is talked to by its family and told stories, if it's shown picture books and read stories - then that child will begin school with a larger vocabulary, a greater ability to listen to and understand instructions, a familiarity with books and stories.

This gives them a huge advantage over a child who isn't talked to as much, who isn't read or told stories.

And that's without even considering the children who speak a different language at home, but are taught in English.

If, because of this early handicap, you are slower to read than others in your class, that's humiliating. You may retreat from this and protect yourself by taking the stance that reading is 'stupid', or that you are not clever enough, and so might as well not bother.

If you find reading so slow and difficult that most of your energy is spent in simply figuring out what the signs on the page are, rather than understanding the information they convey, then reading is going to seem, even more, a pointless and frustrating activity, which you avoid whenever possible.

How much you will then miss! - Not only simple information, and entertainment, but insight into the motivations and emotions of others.

But I'll shut up, and let Dr. Rose speak for himself. (The video is about 8 minutes long.)

One of the great advantages of this form of learning languages - whether written or spoken, your own or a foreign language - is that it can be used for any age-group, at any level.

It also simultaneously teaches a subject and improves reading. For instance, if the subject you're teaching is geography, you take a short text from the geography lesson, and go through the stages of examining the text in detail, taking it apart and reconstructing it. The students not only improve their reading ability - they end by knowing the content of the text better too.

The text you use in class could just as well be about football, or ponies, or whatever else will interest the students.

Dr Rose has data from many schools, which demonstrate that the more able students continue to improve - but the 'less academic' students improve more, and improve faster. The method 'ladders' the weaker students up to a more equal standing with the best students.

Here, some of the teachers who use the Reading To Learn method in New South Wales, talk about it. (This video is about 3 minutes.)

Follow this link to the Authors Electric blog, and you can read about the Stories4Learning site, which I am developing with Alan Hess, a special needs teacher who lives and works in Switzerland.

And fare thee well...

Puss in Boots bows out - Artwork copyright Andrew Price

Puss in Boots bows out - Artwork copyright Andrew Price

Published on January 24, 2014 16:05

January 10, 2014

The World In A Shell

Shell, front view

Shell, front view Shell, seen from above, showing the dragon Here's yet another of my mother's old ornaments. There are two of them, as a matter of fact. My Grandmother Price bought one for her daughter, and one for her daughter-in-law, my mother. My mother liked 'the shells' much more than my aunt. When my aunt grew tired of her shell, she gave it to my mother. They are 'Woolworth's Specials', made of plastic. I loved them. I loved peering in at the little house, with its water-wheel, and the rather blobby person who is watching the boat sail by. I liked to speculate on what would happen when the shell closed.

Shell, seen from above, showing the dragon Here's yet another of my mother's old ornaments. There are two of them, as a matter of fact. My Grandmother Price bought one for her daughter, and one for her daughter-in-law, my mother. My mother liked 'the shells' much more than my aunt. When my aunt grew tired of her shell, she gave it to my mother. They are 'Woolworth's Specials', made of plastic. I loved them. I loved peering in at the little house, with its water-wheel, and the rather blobby person who is watching the boat sail by. I liked to speculate on what would happen when the shell closed.

You might just be able to see that, in the second shell, there is a rather blobby animal, which might be a cow or a donkey, or even a large dog, instead of a blobby person. I cared nothing for the blobbiness. Instead, I was entranced by the fact the blob had a little bridge to enable it to cross the little river.

I don't think my attachment to these oddments is purely sentimental. I think it's a link to a kind of thinking I was much given to as a child. The clue was in that 'what happened when the shell closed?'

Here is something else I was much given to pondering as a child -

There was always a bottle of this around in my childhood. For those who don't know, it held a sticky brown fluid. You put a teaspoonful in a cup, and added hot water, to make alleged coffee - the only kind of coffee I ever tasted, until my aunt (who had been led away from the true faith of tea-drinking by her Polish husband, and was a hardened coffee-addict) introduced me to the real stuff.

But the label - you will see that, on the tray in the picture is a bottle of camp coffee. And on that bottle of camp coffee there must be a label showing exactly the same scene as on the real bottle. And on that bottle must be another, even tinier label - and on that bottle - and so on, down into infinity.

(I once told my partner about this, and he said that years before, on leave in Scotland, he'd gone along to a party given by some people his sister knew. There was an old man sitting in a chair by the fire, and that old man was the man who'd modeled for the Scotsman on the bottle of Camp Coffee. I think he owned the company who made the stuff. All Scots, I tell you, sooner or later meet all other Scots.)

But, back to infinity on a label. I spent many hours, as a child, pummelling my brain as I tried to imagine just how small those pictures within pictures within pictures within pictures became.

Many years later, I came across Flann O'Brien's entirely mad 'The Third Policeman,' which features, among many mad things, a policeman (though not the third one), who halts an attack of one-legged men by painting his bicycle in a colour no one had ever seen before, and riding it past them. They are so disconcerted by the sight of an unknown colour that their campaign collapses.

I nearly did my brain an injury trying to imagine a colour no one had ever seen before. The best I could come up with was a kind of muddy purple - which really wouldn't do at all. Everybody has seen muddy purples. - But it highlights the difficulty of getting outside your usual frame of reference. Is it ever really possible?

Answers - if you have them - and unknown colours - by first class snipe, please.

Published on January 10, 2014 16:05

January 5, 2014

Working Process Blog Tour #mywriting process

Today I'm taking part in the My Writing Process Blog Tour.

I was invited to take part by my friend and fellow Scattered Authors Society member, Karen King. Thanks Karen! - and you can read Karen's Writing Process Blog here - http://www.karenking.net/blog/read_92505/my-writing-process-mywritingprocess.html

1/ What am I working on? A couple of things. Not long ago I finished a book, set in the 19th Century, about a boy escaping from bad treatment. He runs away from a farm in East Scotland, where he's been bound 'apprentice' - but, in truth, is little more than a slave.

He runs without any idea of where he's going - and falls in with a couple of border collies. The dogs recognise him as a stray pup and take him under their paw. The boy, liking their company, follows them.

The dogs are making their way, alone, back to their croft on the Isle of Mull. I've read that herd dogs really did make their own way home, like this. It's a book I greatly enjoyed writing and researching. (For more about this book, follow this link.) It's with my agent at the moment. I mention it here because there will certainly be more work to do on it, whether my agent can interest a publisher or not. If no publisher will take it on, I shall self-publish, but even so, it will probably need another edit.

The other book I'm working on is rather different from my usual vein. It's probably an adult book, though perhaps might squeeze under the wire as a Young Adult. It's set in the present day, and has one really wicked, heartless female character. On her agenda, as I write, are fraud, theft, murder and some psychological torture to pass the time.

The other characters in the book are completely unsuspecting - lambs playing with a tiger.

The book doesn't have a title at the moment - I'm not sure if I can finish it - and I don't know how it's going to end. Or who's going to survive. But I am following the characters with interest!

2/ How does my work differ from others of its genre?

Elfgift by Susan Price I was once re-reading a book of mine, Elfgift, because I was going to be using it in a workshop at a school. It had been years since I'd written it, and it was almost like reading a book by someone else. I noticed something I hadn't even thought about while writing it - how much it focused on how things felt. How heavy a helmet was, how rough ground makes you stumble and twists knees and ankles. It seemed to me that not many other books I've read in the genre - and I've read a lot - are as insistent on how it feels to be in that world.

Elfgift by Susan Price I was once re-reading a book of mine, Elfgift, because I was going to be using it in a workshop at a school. It had been years since I'd written it, and it was almost like reading a book by someone else. I noticed something I hadn't even thought about while writing it - how much it focused on how things felt. How heavy a helmet was, how rough ground makes you stumble and twists knees and ankles. It seemed to me that not many other books I've read in the genre - and I've read a lot - are as insistent on how it feels to be in that world.Not very long after - a month or so - I met a journalist who was writing a review/article about me. One of the comments he made was, 'I like the physicality of your writing. When you write a battle, you never forget that swords have weight, and when you hit someone, it jars up your arm. And that a battle is noisy, and tires you out.'

I thought: so someone else thinks that of my writing too! I felt quite proud.

It is something I try to bear in mind when I'm writing. I was once reading a historical novel where a troop of soldiers, carrying the very long rifles of their period, climbed a steep wooded hillside in the dark. The writer summed this up in a line - 'When they reached the top...' It was a good book, but for a while I was completely distracted from the story. All I could think of was: Has the writer never climbed a wooded hillside in the dark? Even without a rifle? I thought there should have been a mention, even if only a brief one, of the low, unseen branches, the thorns, the briars, the hidden logs underfoot, the twigs thrashing back into their faces - all the things that would have made it difficult.

In oral story-telling, there is a formula, repeated whenever the hero or heroine has to climb a glass mountain, or travel seven miles of steel thistles - 'That's easy to tell, but hard to do.' When I'm writing, I try to keep in mind that what I'm making my characters go through may be easy for me to write, but a lot harder for them to do.

3/ Why do I write what I do? When I'm asked this, I always remember C. S. Lewis' maxim that a writer writes 'from the permanent furniture of their mind.' So if you have a lifelong interest in sailing, then sailing ships are going to appear in your work.

I have a lifelong interest in folk-lore and mythology, in tales of ghosts and witches, shapeshifters and the supernatural... So these things tend to feature in my work rather a lot.

The other side of magic and the supernatural set in the past is often tales of technological wonder set in the future, so I've also written the Sterkarm books, which pitch 16th century rievers against 21st century 'Elves.' They're out of print - though my agent and I are negotiating their republication.

I also wrote the Odin's Voice trilogy, which tells of a

'Odin's Voice' by Susan Pricefuture where there are colonies on Mars and people worship the ancient Greek and Nordic Gods.

'Odin's Voice' by Susan Pricefuture where there are colonies on Mars and people worship the ancient Greek and Nordic Gods.So Mythology got in there again! - The other books in the trilogy are Odin's Queen and Odin's Son.

4/ How does your writing process work?

I usually start with an idea, and then ask myself questions. The Sterkarm Handshake started with me wanting to write about the Border reivers, but without writing an historical book. How could I put the characters from the 16th Century side by side with characters from the 21st Century? - With a Time Machine.

Okay, but where would the Time Machine have come from? Who would have developed it? - A Multi-National Company. Who would be using it to take fossil fuel from the past, so they could sell it in their own time.

Okay, but what characters will I need to tell this story? - Some characters from the 16th Century side. Say, a Border Reiver chief and his son... And some characters from the 21st Century side, say a company executive.

I then do a lot of research and thinking, to build up an idea of what this world is like. What would they wear, eat, drink? What are their houses like, and how are they furnished? How would they spend a typical day?

Some events in the story will arise from this research, but I don't usually have a very detailed idea of how the story is going to work out.

I generally write about three-parts of a draft, and then try to work out a plan for how it's going to end. As the ending comes more into focus, I nearly always have to rewrite what I've already done. I will do at least three rewrites anyway, and probably more.

I don't have set writing hours, and sometimes don't write anything at all for days. Then I might write all night. Sometimes I have to go to a pub and write there, to get anything done. It always seems easier to write away from home, for some reason.

The first draft is a slog. Rewrites are much more fun - because by then the worst of the hard work is done. The plot works, more or less, and I can go deeper into the character's motivations, or pile on atmosphere... Getting a plot to work, for me, is the worst part of the work. I look forward to the rewrites.

Next week I hand over to Catherine Czerkawska, an experienced and powerful writer of plays, short stories and novels. Read her blog here.

Published on January 05, 2014 16:05

December 27, 2013

Returning Home At One In The Morning

The curly writing underneath this charming little scene says, 'Returning home at one in the morning.'

It's another of my mother's ornaments, saved from the clearance when my parents' house was sold.

I was never, never going to let this one go anywhere except my house. It always fascinated me.

Originally, it belonged to my mother's step-father. After he died, my grandmother didn't want it and my mother, who'd always liked it, took it home with her.

She called it 'the fairing', which I didn't understand. Mom explained that ornaments like it were given away as prizes at fairs. It's about a hand-span high, and made of some cheap, heavy china.

As a child, I was fascinated by its miniatureness. I used to love peering into the little bed, with its curtains, pillow, sheets and coverlet. I loved the fact that there was a little chair for the husband to be dragged over, and a little po rolling from under the bed.

Since PC didn't exist in my childhood, I hardly noticed that it showed a scene of domestic violence - something unknown in my immediate family. I thought it was funny. The little wife was beating her little husband because he'd come home at one in the morning! And the weaker woman was beating the stronger man - hilarious! (As a child, I'm glad to be able to say, I found newspaper accounts of husbands beating wives (or vice-versa) and parents beating children, flatly unbelievable - as unbelievable as pigs flying. It was simply outside my experience. This little ornament seemed quaint, as one showing a horse riding a man might, or a mouse chasing a cat.)

The husband's kicking foot has been broken off, and whatever the woman was beating him with - a slipper? a rolling pin? frying pan? - has also disappeared. Although it's an antique, I don't need to be told that it isn't worth anything.

Aren't those natty pyjamas?

Aren't those natty pyjamas?I was intrigued by a display in York Museum, though. They had many, many fairings, of all sizes, some a foot square. Some were coloured like the one pictured here, others were blue, or pink, or yellow all over. Several were plainly from the same series as 'One in the Morning' with similar characters. But they didn't seem to have a single example of 'One in the Morning.'