Paul Gilster's Blog, page 235

December 17, 2012

An Early Nod to Beamed Propulsion

It’s always interesting how different strands of research can come together at unexpected moments. The last couple of posts on Centauri Dreams have involved new work on Titan, and early references in science fiction to Saturn’s big moon. The science fiction treatments show the appeal of a distant object with an atmosphere, with writers speculating on its climate, its terrain, and the bizarre life-forms that might populate it. But early science fiction also proposed ways of reaching the outer Solar System, some of them echoed only decades later by scientists and engineers.

Christopher Phoenix wrote in yesterday commenting on chemist and doughnut-mix master E. E. “Doc” Smith, who when he wasn’t working for a midwestern milling company wrote space operas like The Skylark of Space on the side. Noting that Titan plays a major role in Smith’s story Spacehounds of IPC, Phoenix pointed out that the tale may be the first appearance in science fiction of beamed propulsion. This was just weeks after I had read an upcoming paper by Centauri Dreams regular Adam Crowl on interstellar propulsion concepts in which Crowl singled out E. E. Smith’s prescience, citing this same story.

The beauty of beamed propulsion is that you leave the propellant behind, thus slipping out of the noose of the rocket equation. Solar sails — using only the power of sunlight absent microwave or laser beaming — go back to the earliest days of astronautics — even Kepler had pondered the possibilities when studying comets and the effect of what he thought of as a solar wind upon their tails. Seeing that comet tails always pointed away from the Sun, Kepler homed in on the obvious analogy with seafaring vessels, wondering if fleets of space-borne ships might someday explore the Solar System. Thus his 1610 letter to Galileo:

There will certainly be no lack of human pioneers when we have mastered the art of flight… Let us create vessels and sails adjusted to the heavenly ether, and there will be plenty of people unafraid of the empty wastes. In the meantime, we shall prepare for the brave sky-travelers maps of the celestial bodies. I shall do it for the moon, you Galileo, for Jupiter.”

But sunlight drops off precipitously with distance. As Crowl noted, Smith’s concept in Spacehounds of IPC was to send energy from an installation on a planet, leaving the heavy powerplant off the vehicle by beaming intense coherent electromagnetic waves at the vessel. Here, as Phoenix did in his comment, we can cite Smith himself, who invokes Solar System locales that seemed plausible in the 1930’s, along with something called ‘Roeser’s Rays’ that supply the needed energy to the spaceships:

Power is generated by the great waterfalls of Tellus [Earth] and Venus—water’s mighty scarce on Mars, of course, so most of our plants there use fuel—and is transmitted on light beams, by means of powerful fields of force to the receptors, wherever they may be. The individual transmitting fields and receptors are really simply matched-frequency units, each matching the electrical characteristics of some particular and unique beam of force. This beam is composed of Roeser’s Rays, in their energy aspect…

…this whole thing of beam transmission is pretty crude yet and is bound to change a lot before long. There is so much loss that when we get more than a few hundred million kilometers away from a power-plant we lose reception entirely. But to get going again, the receptors receive the beam and from them the power is sent to the accumulators, where it is stored. These accumulators are an outgrowth of the storage battery…

…From the accumulators, then, the power is fed to the converters, each of which is backed by a projector. The converters simply change the aspect of the rays, from the energy aspect to the material aspect. As soon as this is done, the highly-charged particles—or whatever they are—thus formed are repelled by the terrific stationary force maintained in the projector backing the converter. Each particle departs with a velocity supposed to be that of light, and the recoil upon the projector drives the vessel, or car, or whatever it is attached to. Still with me?”

The reader may or may not be, but these early science fiction magazines were filled with long blocks of exposition as characters explained various scientific principles and fabulations to a rapt audience. Indeed, the letter columns of the science fiction pulps were filled with critiques and analyses of the various scientific ideas on display, some of them highly detailed. For more on this, there is no better source than John Cheng’s essential study Astounding Wonder (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

I’ve always been fascinated by the first appearances of concepts in the early science fiction magazines, but this one had escaped me. A good thing Adam Crowl and Christopher Phoenix were on the case! As Phoenix points out, the energy of “Doc” Smith’s imaginary ‘Roeser’s Rays’ can somehow be used to produce thrust in any direction as opposed to bouncing photons off a departing sail, which would require extreme precision to keep the sail within the collimated beam and navigating to the correct destination. Says Phoenix: “I’ve seen a lot of rocket ships and mysterious “inertial drives” and “warp drives” in early SF, but never a spaceship that rode a beam until Spacehounds of IPC, and this space opera tale could be quite significant for that fact.”

Indeed. In keeping with so much science fiction of the time, Smith’s characters are wooden, his plots lurid, but the appeal of this story is in his imagined technologies. Nor was he above tinkering with a text when asked to adapt magazine work into a novel. Crowl noticed that when you compare the 1947 novelisation of “Spacehounds of IPC” to the earlier 1931 text, Robert Goddard disappears. It was through Goddard’s efforts in liquid fuel propulsion that interplanetary development began in the original, but after Goddard’s death in 1945, the latter disappears from the ensuing novel. Interesting too that Smith always considered Spacehounds of IPC his best work, true science fiction as opposed to what he called the ‘pseudo-science’ that had animated his Skylark novels, where handwaving FTL effects are commonplace.

I notice that P. Schuyler Miller, long a reviewer for Astounding, regarded Spacehounds of IPC to be Smith’s most believable book, a serious upgrade over earlier work. The story was serialized in Amazing Stories beginning in July of 1931 and has had both hardcover and paperback editions in the years since. In fact, the hardcover edition of 1947 was the first book ever published by Fantasy Press, a nice collector’s item. Like Carl Wiley, who under the pseudonym ‘Russell Saunders’ wrote the first article on solar sails for a science fiction magazine (Astounding, in May of 1951), E. E. Smith dished up an SF look at beamed propulsion thirty years before the invention of the laser, a fascinating extrapolation from the technology of his era.

December 14, 2012

Titan: A Vast, Subsurface Ocean?

Yesterday’s look at a major river on Titan took on a decidedly science fictional cast, but then Titan has always encouraged writers to speculate. Asimov’s “First Law” (1956) tackles a storm on Titan as a way of dealing with the Three Laws of Robotics. Arthur C. Clarke filled Titan with a large human colony in Imperial Earth (1976), and Kim Stanley Robinson used Titanian nitrogen in his books on the terraforming of Mars. As far back as 1935, Stanley G. Weinbaum was writing about a frozen Titan and the struggles of early explorers on that world.

The list could go on, but right now the focus stays on Cassini, which with funding continued through 2017 will continue to give us new and striking discoveries like the river dubbed the moon’s ‘little Nile’ feeding into Ligeia Mare. Nor do I want to ignore the recent work from Howard Zebker (Stanford University) and team, who have been working with Cassini radar data and new gravity measurements to tell us more about the internal structure of Titan and its shape. The idea that Titan boasts a deep subsurface ocean is consistent with the results in this study, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union earlier this month.

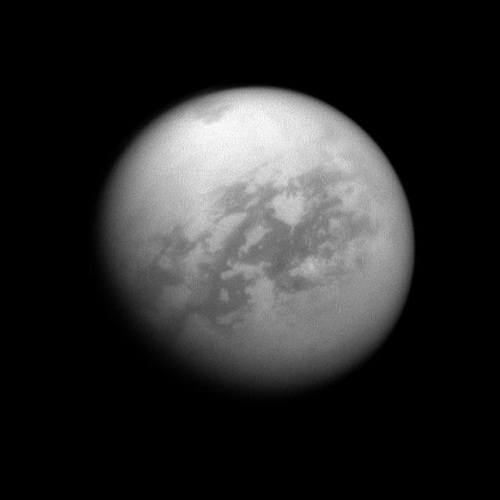

Image: A Cassini view of Titan, with Kraken Mare, a sea of liquid hydrocarbons, visible at the top of the image. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Sept. 14, 2011 using a spectral filter sensitive to wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 938 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (1.9 million kilometers) from Titan and at a Sun-Titan-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 26 degrees. Image scale is 7 miles (12 kilometers) per pixel. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

The model of Titan now accepted is that beneath an icy crust perhaps 100 kilometers thick is an ocean of uncertain depth. Below that is a core that is most likely a combination of ice and rock. The ocean is thought to remain liquid thanks to heat generated by the decay of radioactive elements in the core that go back to the earliest days of the Solar System. Zebker’s team has been analyzing how Titan spins on its axis, and specifically how much it resists any changes in that spin, a factor known as the moment of inertia. He explains the result:

“The moment of inertia depends essentially on the thickness of the layers of material within Titan. The picture of Titan that we get has an icy, rocky core with a radius of a little over 2,000 kilometers, an ocean somewhere in the range of 225 to 300 kilometers thick and an ice layer that is 200 kilometers thick.”

That 200 kilometer ice layer doubles the previous estimate and implies there may be less rock in the core and more ice than had previously been estimated. But the work also has to contend with the fact that Titan’s shape is distorted by the gravitational influence of Saturn, flattening it slightly at the poles. And it turns out that Titan’s shape is more distorted than would be accounted for by the basic gravitational model. Working the numbers, Zebker finds that the density of material under the poles would have to be slightly greater than that under the equator.

Reasoning that liquid water is denser than ice, Zebker’s team comes up with this model: Thinner ice at Titan’s poles — about 3000 meters thinner than the average — and thicker ice at the equator, by about the same margin. The researchers used the combination of gravity and topography to suggest that the average thickness of the icy layer over the ocean is 200 kilometers. The variation in internal heat that would account for the changes in surface thickness may well be the result of tidal influences as Titan orbits the gas giant. Zebker again:

“The variation in the shape of the orbit, along with Titan’s slightly distorted shape, means that there is some flexure within the moon as it orbits Saturn. The planet’s other moons also exert some tidal influence on Titan as they all follow their different orbits, but the primary tidal influence is Saturn. The tides move around a little as Titan orbits and if you move anything, you generate a little bit of heat.”

So the internally generated heat that keeps Titan’s ocean liquid comes not only from radioactive elements but tidal interactions between Titan and Saturn as well as between Titan and the planet’s other moons. Putting these factors into play coupled with analysis of the moon’s moment of inertia allows us to piece together a picture of its internal structure. It’s worth noting that as we continue the study of the outer system, we’re now looking at subsurface ocean possibilities in many places, from Triton to Pluto and conceivably even further out into the Kuiper Belt.

The Titan we’re looking at through Cassini is a long way from the Titan Stanley G. Weinbaum imagined in the story I mentioned at the top, which was “Flight on Titan” (Astounding, January 1935). Weinbaum has a Titan that’s more chilly than frigid, one in which the characters flee native lifeforms as they make a forced march over Titanian mountains, all the while carrying the objects of the journey from Earth, the rare gems called ‘flame orchids.’ Weinbaum’s fantasy Titan bears little resemblance to the hazy, hydrocarbon-saturated surface we see, but it’s a testament to the fact that we have always peopled unknown worlds with the objects of our imagination, a compulsion that, given the means, leads inevitably to journeys of discovery.

December 13, 2012

Titan’s Big River (and Thoughts of Jules Verne)

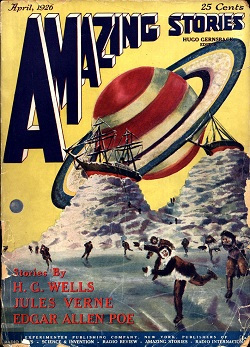

One of the wonderful things about daily writing is that I so often wind up in places I wouldn’t have anticipated. Today’s topic includes the discovery of a long river valley on Titan that some are comparing to the Nile, for reasons we’ll examine below. But the thought of rivers on objects near Saturn invariably brought up the memory of a Frank R. Paul illustration, one that ran as the cover of the first issue of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories in April of 1926. The bizarre image shows sailing ships atop pillars of ice, a party of skaters, and an enormous ringed Saturn.

Is this Titan? The answer is no. The illustration is drawn from the lead story in the magazine, Gernsback’s serialized reprint of Jules Verne’s Off on a Comet, first published in French in 1877 under the title Hector Servadac. A huge comet has grazed the Earth and carried off the main characters, who must learn how to survive the rigors of a long journey through the Solar System, much of the time exploring their frozen new world on skates. I’ll spare you the plot details, but after a perilous fly-by of Jupiter they swing into Saturn’s realm:

…this remarkable ring-system is a remnant of the nebula from which Saturn was himself developed, and which, from some unknown cause, has become solidified. If at any time it should disperse, it would either fall into fragments upon the surface of Saturn, or the fragments, mutually coalescing, would form additional satellites to circle round the planet in its path.

To any observer stationed on the planet, between the extremes of lat. 45 degrees on either side of the equator, these wonderful rings would present various strange phenomena. Sometimes they would appear as an illuminated arch, with the shadow of Saturn passing over it like the hour-hand over a dial; at other times they would be like a semi-aureole of light. Very often, too, for periods of several years, daily eclipses of the sun must occur through the interposition of this triple ring.

If only Verne had been around to see Cassini’s images! Verne’s cometary voyagers can study the heavens with a certain detachment because the comet they are on, called Gallia, turns out to be circling back around toward the Earth, and they believe they will have the prospect of getting home. Off on a Comet is a lively tale. It would be interesting to see what Brian Stableford, who has translated so many early French tales of science fiction into English, would do with the text. Gernsback used a 1911 edition edited and I assume translated by Charles Horne, a New York-based college professor.

On to Titan

Jules Verne had no trouble concocting plots — in addition to his short stories, poems and plays (not to mention numerous essays), he wrote 54 novels in the series called Voyages Extraordinaires between 1863 and 1905. Here among much else are the familiar touchstones From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1869). We can only wonder what a Verne armed with Cassini’s latest imagery might have come up with. Take a look, for example, at the river system in the photo below. No skating here, but a boat might work.

It goes without saying that we’ve never seen a river so vast anywhere beyond our own planet, and it does bear a certain resemblance to the Nile, with which it is being compared. What Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke might have given to have had a similar aerial view of the Nile, the search for whose headwaters brought them so much grief and personal animosity. This ‘Nile’ stretches for more than 400 kilometers from its origins to a large sea, its dark surface suggestive of liquid hydrocarbons along the entire length of this high-resolution radar image.

We’re looking at Titan’s north polar region, with a river valley flowing into Ligeia Mare, a sea larger than Lake Superior on Earth. We should actually consider this river a mini-Nile, given that its namesake runs for fully 6700 kilometers, but acknowledging its unique significance (thus far) in our exploration of Titan, the comparison still seems justified. In any case, the river has much to tell us about Titan if we can learn how to read it. Thus Jani Radebaugh, a Cassini radar team associate at Brigham Young University:

“Though there are some short, local meanders, the relative straightness of the river valley suggests it follows the trace of at least one fault, similar to other large rivers running into the southern margin of this same Titan sea. Such faults – fractures in Titan’s bedrock — may not imply plate tectonics, like on Earth, but still lead to the opening of basins and perhaps to the formation of the giant seas themselves.”

Image: Cassini’s view of a vast river system on Saturn’s moon Titan. It is the first time images from space have revealed a river system so vast and in such high resolution anywhere other than Earth. The image was acquired on Sept. 26, 2012, on Cassini’s 87th close flyby of Titan. The river valley crosses Titan’s north polar region and runs into Ligeia Mare, one of the three great seas in the high northern latitudes of Saturn’s moon Titan. It stretches more than 200 miles (400 kilometers). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI.

One day we may have a floating probe on Titan that can trace the course of such a river, working its way out into a dim sea under a sky whose dense cloud would doubtless screen the ringed Saturn from view. What a journey that would be. Even without the garish Frank Paul colors or the wild Vernian imagination, think of human instruments sending back data from a methane sea. Two proposals — Titan Lake In-situ Sampling Propelled Explorer (TALISE) and Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) show us what we might do with near-term technology to make this a reality.

December 12, 2012

Widening the Habitable Zone

Finding a way to extend the classical habitable zone, where liquid water can exist on the surface of a planet, is a project of obvious astrobiological significance. Now a team of astronomers and geologists from Ohio State University is making the case that their sample of eight stars shows evidence for just such an extension. The stars in question, drawn from a dataset created by the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher spectrometer at the European Southern Observatory in Chile, were selected because they match up well with the Sun in terms of size, age and composition. Seven of the eight, however, show signs of much more thorium than found in our star.

It’s an interesting result, as seen in this Ohio State news release. The slow radioactive decay of elements like thorium, potassium and uranium, all found in the Earth’s mantle, helps to heat the planet. These are elements present at planetary formation and, according to Ohio State’s Wendy Panero, they are involved in producing enough heat to drive plate tectonics, which some believe to be a factor in maintaining our planet’s oceans. All this is in addition to the sources of heat convection found in the Earth’s core, which play a comparable role in crustal movement.

The work was presented last week at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco by Cayman Unterborn, a graduate student at Ohio State who is working under Panero. Unterborn’s thesis: More thorium in a stellar interior indicates that the interior of planets found around the star would be warmer than the Earth. He notes that one of the stars in the HARPS survey contains 2.5 times more thorium than the Sun. Unterborn’s calculations show that any terrestrial planets forming around that star would generate as much as 25 percent more heat than the Earth, providing a long-lasting driver for plate tectonics. The warmer planet would have a habitable zone farther from its star as well, supported by the additional internal heat.

Image: An artist’s impression of the ‘super-Earth’ HD 85512 b. Is it possible that a planet like this is warmer internally than the Earth, allowing life to form over a wider habitable zone? Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser.

The cautious Unterborn is aware that he’s looking at a small sample:

“If it turns out that these planets are warmer than we previously thought, then we can effectively increase the size of the habitable zone around these stars by pushing the habitable zone farther from the host star, and consider more of those planets hospitable to microbial life. At this point, all we can say for sure is that there is some natural variation in the amount of radioactive elements inside stars like ours. With only nine samples including the sun, we can’t say much about the full extent of that variation throughout the galaxy. But from what we know about planet formation, we do know that the planets around those stars probably exhibit the same variation, which has implications for the possibility of life.”

The Ohio State researcher notes that thorium is more energetic and has a longer half-life than uranium. Planets rich in the element would tend to remain hot longer than the Earth, which gets most of the heat of its radioactive decay from uranium. As to why we wind up on the short end of the stick when it comes to thorium, Unterborn believes it harks back to the exploding stars that seeded local space with heavy elements long before our planet formed:

“It all starts with supernovae. The elements created in a supernova determine the materials that are available for new stars and planets to form. The solar twins we studied are scattered around the galaxy, so they all formed from different supernovae. It just so happens that they had more thorium available when they formed than we did.”

These results are clearly preliminary, and Jennifer Johnson (Ohio State), a co-author of the study, points to the need to expand its scope. One way to do that is to analyze noise in the HARPS data, something that is now on Unterborn’s to-do list, after which the team plans to expand the search to additional Sun-like stars. If there are indeed large numbers of stars whose basic composition creates planets that generate more internal heat than the Earth, then we need to consider the implications for how we analyze habitable zones and their longevity.

December 11, 2012

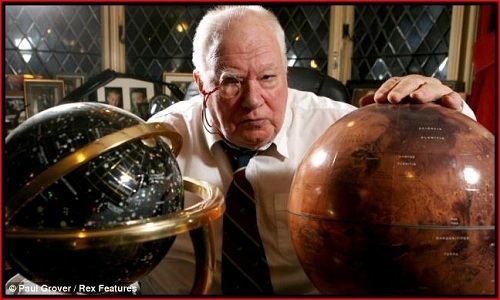

Thoughts on Patrick Moore

Patrick Moore, the legendary figure of British astronomy who died recently at his home in West Sussex, was deeply familiar with Ptolemy. The latter, a 2nd Century AD mathematician and astronomer, was the author of the Almagest, an astronomical treatise that presented the universe as a set of nested spheres and assumed a geocentric cosmos. Moore’s comprehensive knowledge of astronomy’s history would naturally have included the Almagest and probably Ptolemy’s astrological musings as well, but a different Ptolemy was a figure even more important to him, a cat of that name who was with him when he died. The author of 2012′s Miaow!: Cats Really are Nicer Than People! never hid his love for his feline friends.

I admire a man who, when faced with the reality that further treatments are unproductive, simply announces that he wants to go home. And go home he did, to the town of Selsey and the house called Farthings, where he died among family and friends. Moore was a man of fierce views and simple integrity whose generosity was uncommon. In a career in which he hosted the BBC show ‘The Sky at Night’ for an unprecedented 55 years, he inspired countless young people to explore the heavens. Brian May, the guitarist who published a book on astronomy with Moore, noted the latter’s devotion to his audience in a remembrance published in The Guardian.

In his private life Patrick was astoundingly giving. His dedication to young aspiring astronomers was legendary. He replied to every letter, responded to questions, helped students with gifts of equipment and the most precious gift of all – his time. He personally tutored some he thought particularly promising, and sponsored others through higher education; he gave away any income he made to the point where he had no security himself except that which his friends supplied.

‘The Sky at Night’ first appeared in 1957, and it is a remarkable fact that in the years since, Moore missed only a single episode, felled by a salmonella-laden egg in 2004. He could have gone to Cambridge and pursued an academic career, but when World War II came he lied about his age and joined Bomber Command, where he became a navigator. He called himself a ‘reluctant bachelor,’ and said that he felt the same about his fiancée Lorna in 2012 as he did in 1940, not long before she was killed by a German bomb. Love ran deep. He would never marry but would go on to parlay his extensive learning and air of eccentricity into the work of a lifetime.

The gifted amateur used a 12-inch reflector, specializing in lunar observations of a quality so high that he was chosen to be the first outside the Soviet bloc to see the results of the Luna 3 probe, showing images from the craft on the air. Moore was dealing with live TV in those days, and not all his plans worked out, as when technical problems compromised his coverage of Luna 4 transmissions, and at times his attempts to get a live telescopic view of a celestial object were ruined by cloud cover. None of this mattered and some of the glitches, such as his swallowing a fly that buzzed into his mouth, only added to the eccentric charm and reputation of the presenter. Many will remember Moore’s on-air work during the Apollo missions, which extended to later reporting on both Pioneer and Voyager. His Wikipedia article has more.

Much is being said in remembrance of Moore all over the Internet — see this obituary in The Telegraph, for example, in addition to the BBC article by Brian May that I linked to above. Moore the television presenter is remembered just as fondly as Moore the author. He began his work with Guide to the Moon in 1953 and continued for over 60 titles, much of the time working on the same 1908 Woodstock typewriter.

This morning I’ve been thumbing through the pages of his 1984 book Travellers in Space and Time, an illustrated journey through the cosmos that takes us as far as Andromeda, but I’m also thinking of titles that were older still, like The Picture History of Astronomy (1964) and Watchers of the Stars (1974). Books like these and Moore’s practical tomes on amateur astronomy brought celestial matters down to Earth, igniting enthusiasm and stoking the fires of young careers. This grand, ebullient man with the trademark monocle was indispensable, impossible to replace. “There will never be another Patrick Moore. But we were lucky enough to get one,” wrote May in his tribute. Do note that May has also set up a Patrick Moore website where members of the public he spoke to with such passion can leave their remembrances.

December 10, 2012

Interstellar Flight: The View from Kansas

If Kansas may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think about interstellar matters, be aware that its state motto is ‘Ad Astra Per Aspera’ — to the stars through difficulties. That’s a familiar phrase for anyone who has pondered the human future in space, appearing in countless science fiction stories and often invoked by those with a poetical streak. It turns out that the Kansas motto was not, however, the work of some percipient 19th Century Robert Forward figure, but of one John Ingalls, a lawyer, scholar and statesman who introduced the motto as far back as 1861. And while its roots were in the coming Civil War, the story of Ingalls’ motto is so entertaining that it merits inclusion here, as reported by biographer G. H. Meixell:

“I was secretary of the Kansas state senate at its first session after our admission in 1861. A joint committee was appointed to present a design for the great seal of the state and I suggested a sketch embracing a single star rising from the clouds at the base of a field, with the constellation (representing the number of states then in the Union) above, accompanied by the motto, “Ad astra per aspera.” If you will examine the seal as it now exists you will see that my idea was adopted, but in addition thereto the committee incorporated a mountain scene, a river view, a herd of buffalo chased by Indians on horseback, a log cabin with a settler plowing in the foreground, together with a number of other incongruous, allegorical and metaphorical augmentations which destroyed the beauty and simplicity of my design.”

It was ever thus, and not just for politicians with an artistic bent. Any writer can tell stories about botched copy edits that would make even Ingalls shake his head in disbelief.

Space advocate Steve Durst was well aware of the history embedded in Ingalls’ motto, but also taken with the idea of Kansas in a more astronomical context. After numerous trips to the state, he would go on to found an organization called Ad Astra Kansas, focusing on high-tech and space research but with a wider charter that includes getting the word out about interstellar matters through education. The idea grew out of two other projects likewise affiliated with Durst’s Space Age Publishing Company: The International Lunar Observatory Association and an international series of public presentations called the Galaxy Forum. Durst says he has always been looking for “something broad that would be inspirational, directional, iconic, symbolic,” and in promoting the concept of interstellar flight, he has surely found it.

Image: Publisher and space activist Steve Durst, standing in front of the “Ad Astra Per Aspera” stained-glass artwork at the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center in Hutchinson just before Galaxy Forum Kansas on September 22, 2012.

Ad Astra Kansas came to my attention when I flew to San Jose last July to speak at a Galaxy Forum on the 4th and meet the energetic Durst, along with marketing editor Michelle Gonella. The organization is now a decade old, having begun its Ad Astra Kansas News in 2001, a publication that continues today under the editorship of Jeanette Steinert. The first Ad Astra Kansas Day was held in 2003, inaugurating a series of such meetings in various Kansas venues with an emphasis on business and education as space development continues. One of these is the Kansas Cosmosphere, a world-class aerospace facility in Hutchinson that seems to exemplify the anomalous nature of the enterprise. Here is a quiet farming community of some 42,000 people that boasts a major venue showcasing space exploration from the V-2 to Apollo.

What else could be created here? Durst talks about an interstellar research and development initiative, perhaps created as an archive or, long-term, a research center with an interstellar focus. Meanwhile, the organization continues to play a midwestern role in the Galaxy Forum program that began in Silicon Valley. Operating from his headquarters in Hawaii, home to ILOA, and an office in California, Durst, Phil Merrell, and Joseph Sulla of the ILOA Galaxy Forum program in Hawaii have, along with Gonella, expanded the forums around the world. They began July 4, 1984, as discussions of lunar exploration but by 2008 the focus had turned to the galaxy, with sessions as far afield as Canada, Beijing, Singapore and Japan. 2011 saw eleven Galaxy Forums from Shanghai to Bangalore, Hawaii and New York, bringing speakers and the general public together to discuss space and the human future in the broadest possible context.

My focus last July in San Jose’s Galaxy Forum was on the question of nearby targets for deep space missions, ‘nearby’ being defined as objects between the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt all the way to the Alpha Centauri stars. It was a good session, held at the city’s Tech Museum on July 4. Jon Lomberg had flown in from Hawaii and Seth Shostak was on hand from the SETI Institute. Durst’s hope is to provoke what he calls ‘galaxy consciousness,’ a way of looking at the future that leverages near-term projects like the lunar observatory but points beyond:

“We are at the start not just of new century but a new millennium. The Galaxy Forum is premised as much as anything on the fact that this is a new domain of learning for us, for all of humanity. Ninety years ago, before Hubble’s findings, we didn’t know there were galaxies or that we were part of one. Even today we have the sense that all those stars we see on a clear night comprise the universe, but that’s not true — it’s just a small patch of our own galaxy that we see. Professionals understand that, but in general educational practice from high school and early college down, there isn’t an awareness that between the finiteness of the Solar System and the infiniteness of the cosmos there is this larger knowable domain of the galaxy to explore.”

That’s a confounding fact but true — I still find myself having to explain the difference between ‘interplanetary’ and ‘interstellar’ at the oddest moments. Thus the idea of ‘galaxy consciousness’ is a praiseworthy target, but one that will require more than a generation of work. The idea grew out of Durst’s earlier work with the International Lunar Observatory Association, which itself emphasizes that its mission is “to expand human understanding of the cosmos through observation from our Moon.” The original ILOA mission was conceived as deployment of a 2-meter dish observatory near the lunar south pole, for observations both of the local environment as well as deep space as a way of educating people about the Solar System’s context in the cosmos. But ILOA is also working on a Google X-Prize entrant with the goal of placing a 10-cm optical telescope on the team’s lunar lander scheduled for 2014.

And in September 2012, ILOA signed a memo of understanding with the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences allowing ILOA scientists to conduct observations with the UV telescope set to fly on the Chang’e-3 lunar lander in 2013. With Galaxy Forums set to expand to South America and possibly Antarctica by 2014, ILOA is part observer, part educator, with the goal of having a voice in the changing philosophical perception of our planet’s place in the galaxy. Meanwhile, Ad Astra Kansas is a reminder that deep space begins close to home, in the students whose careers may be launched by education that opens minds to the cosmos. Who knew in 1861 that John Ingalls’ state motto would have that kind of reach?

December 7, 2012

Brown Dwarf Results Promising for Planets

Do planets form easily around brown dwarf stars? Are they actually common? We’re getting a glimpse of the possibilities in new work at the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), where a brown dwarf known as ISO-Oph 102 (also called Rho-Oph 102) is under investigation. In most respects it seems like a fairly run-of-the-mill brown dwarf, about 60 times the mass of Jupiter and thus unable to ignite hydrogen fusion. It’s also tiny, at 0.06 times the mass of the Sun, a dim object in the constellation of Ophiuchus.

The work suggests that in the outer regions of a dusty disk surrounding Rho-Oph 102 there exist the same kind of millimeter-sized solid dust grains found around the disks of young stars. That’s intriguing because astronomers have thought that earlier finer grains would not be able to grow into these larger particles in the cold, sparse disks assumed to be around brown dwarfs. Those that did form were thought to disappear quickly toward the inner disk, where they would be undetectable. The fact that these larger grains are here has interesting implications, according to CalTech’s Luca Ricci, who led the international team performing the study:

“We were completely surprised to find millimetre-sized grains in this thin little disc. Solid grains of that size shouldn’t be able to form in the cold outer regions of a disc around a brown dwarf, but it appears that they do. We can’t be sure if a whole rocky planet could develop there, or already has, but we’re seeing the first steps, so we’re going to have to change our assumptions about conditions required for solids to grow.”

Image: This wide-field view shows the star-forming region Rho Ophiuchi in the constellation of Ophiuchus (The Serpent Bearer), as seen in visible light. This view was created from images forming part of the Digitized Sky Survey 2. Credit: ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2/Davide De Martin.

The disks around brown dwarfs may thus be more similar to those around young stars than we had realized, suggesting that rocky planets may not be uncommon here. We do have a few brown dwarf planets — 2M1207b, MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb and 2MASS J044144 — already in the book, one of them relatively small at 3.3 Earth masses. And a study by Andrey Andreeschchev and John Scalo (University of Texas) has indicated that terrestrial-mass planets should form around these objects as long as there is enough disk material to work with.

Image: Rocky planets are thought to form through the random collision and sticking together of what are initially microscopic particles in the disc of material around a star. These tiny grains, known as cosmic dust, are similar to very fine soot or sand. Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have for the first time found that the outer region of a dusty disc encircling a brown dwarf — a star-like object, but one too small to shine brightly like a star — also contains millimetre-sized solid grains like those found in denser discs around newborn stars. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/M. Kornmesser (ESO).

The ALMA work also found carbon monoxide around the brown dwarf, its first detection in a brown dwarf disk. All this is promising stuff if we want to construct exotic scenarios about what may happen around these dim objects. Lacking the mass to fire hydrogen fusion, a brown dwarf is nonetheless going to emit heat because of its slow contraction due to gravity. Any brown dwarf with terrestrial planets around it is going to be doing a slow fade as it gives up gravitational potential energy. That means that if there is a habitable zone there, it gradually moves inward.

I’ve quoted him on this before, but Centauri Dreams reader Andy Tribick may not mind if I put this comment of his out there again. He’s talking about life around brown dwarfs:

It’d be interesting to come up with some scenarios for evolution on such a planet whose star decreases in luminosity as it ages (as opposed to more conventional stars that brighten as they age) – perhaps life might begin in the cloud layers of an initially Venus-like planet, moving to the surface as the atmosphere cools and the oceans rain out of the atmosphere, and finally moving to a more Europa-like state with the oceans frozen under an ice layer.

The 2004 study by Andreeshchev and Scalo I referred to above concluded that a brown dwarf with the mass of 0.07 solar masses, not all that far off Rho-Oph 102’s 0.06, could produce a habitability duration of a billion years, presumably long enough to get basic life functioning. And because the two scientists are talking about a classic habitable zone definition involving liquid water on the surface, you can see that Andy Tribick’s idea would extend the duration of possible habitability at both ends. Andreeshchev and Scalo themselves can extend habitability out to a surprising four billion years depending on how far they push the Roche limit, which governs how close a planet can be to its host star before it’s torn apart by tidal forces.

So maybe there’s a case for astrobiology around brown dwarfs, objects about which we still have much to learn. Just how common are they? While some scientists have suggested that brown dwarfs might be as common as the M-dwarfs that make up as much as 80 percent of the stars in the Milky Way, the results from WISE — the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer — turn up one brown dwarf for every six stars. That’s still a significant number of objects, and it includes 33 brown dwarfs known to be within 26 light years of the Sun, but the idea of interstellar targets closer than Alpha Centauri, at least stellar targets, is evidently fading from view.

But back to Luca Ricci and team and their work with ALMA. The great news embedded in the story is that ALMA is only partially up to strength. This array of radio telescopes in Chile’s Atacama desert operates at millimeter wavelengths and is intended to consist of 66 instruments when complete, but Ricci’s team worked with just a quarter of the final complement of antennas. In terms of observing planetary system formation, ALMA is already proving its worth, and a completed ALMA installation should be able to give us a close look at Rho-Oph 102:

“We will soon be able to not only detect the presence of small particles in discs, but to map how they are spread across the circumstellar disc and how they interact with the gas that we’ve also detected in the disc,” Ricci said. “This will help us better understand how planets come to be.”

The paper is Ricci et al., “ALMA observations of rho-Oph 102: grain growth and molecular gas in the disk around a young Brown Dwarf,” accepted at the Astrophysical Journal (abstract). The Andreeshchev and Scalo paper is “Habitability of Brown Dwarf Planets,” Bioastronomy 2002: Life Among the Stars. IAU Symposium, Vol. 213, 2004 (full-text).

December 5, 2012

Voyager: Dark Highway Ahead

One rainy night in the mid-1980s I found myself in a small motel in the Cumberlands, having driven most of the day after a meeting and reaching Newport, TN before I decided to land for the night. It’s funny what you remember, but small details of that trip stick with me. I remember the nicking of the wiper blades as I approached Newport, the looming shapes of the mountains in the dark, and most of all the fact that I was thinking about an interstellar mission. I was working on a short story that grew out of the Voyager mission and the experience of those who controlled it.

After a late dinner at a restaurant near the motel, I asked myself what it would be like to be involved in a truly long-term mission. Suppose we develop the technologies to get a probe up to a few percent of the speed of light. If we send out a flyby mission to the nearest stars, we’re talking about a couple of centuries of flight time, or maybe a bit less. It’s inevitable, then, that a mission like this would be handed off from one generation to the next. Clearly the people who worked the stellar encounter would have been born and matured long after the mission left.

My story involved a man who worked on such a mission as the probe closed within a year of its encounter with Epsilon Indi, a man who learned that, although he was only in his 40s, he was dying and wouldn’t see the probe reach its destination. Back in those days the many avenues of exoplanet investigation weren’t yet clear and we had no good data on planets around other stars, so the big question was whether the probe would find planets around the star or not. But the larger issue was the human perspective on time and commitment even in the face of mortality.

I think about things like that every time I read the latest news from Voyager. The most recent information involves a so-called ‘magnetic highway’ and the behavior of charged particles in the heliosheath as Voyager 1 pushes closer to interstellar space. I can check this morning to see that the spacecraft is now 18,462,802,513 kilometers from the Earth, which works out to a one-way light time of just a bit over 17 hours. Voyager 1 was launched on the 5th of September, 1977, but it’s still a live presence that should keep sending back data perhaps for a decade.

There are surely people working around the periphery of the ongoing Voyager missions who weren’t born when they were launched. What would it be like for a civilization like ours to watch a true interstellar mission over the course of lifetimes, a deep space presence that, no matter what else we found ourselves doing would periodically galvanize the attention, reminding all of us that it was still out there, a heart still beating, a mind (human or artificial) still sending back data. There is something grand in that notion that calls up not just physics and astronomy but archaeology, the recovery of history and perspective, of humanity considered over deep time.

But of course when you’re working a mission, you have very practical work to do. Stamatios Krimigis (JHU/APL) is principal investigator of Voyager’s Low-Energy Charged Particle (LECP) instrument. Voyager 1 crossed the so-called ‘termination shock’ in late 2004 and moved into the heliosheath, where the solar wind has slowed and become turbulent. For a time the solar wind dropped to zero and the intensity of the magnetic field began to increase. I sense the practical scientist as well as a bit of the philosopher in Krimigis as he describes all this:

“The solar wind measurements speak to the unique abilities of the LECP detector, designed at APL nearly four decades ago. Where a device with no moving parts would have been safer – lessening the chance a part would break in space – our team took the risk to include a stepper motor that rotates the instrument 45 degrees every 192 seconds, allowing it to gather data in all directions and pick up something as dynamic as the solar wind. A device designed to work for 500,000 ‘steps’ and four years has been working for 35 years and well past 6 million steps.”

A four year design still functioning after 35 is a tribute to the engineering that conceived it and a reminder of the timescales that missions into much deeper space will one day have to reckon with. As to Voyager, has it entered a new region of space? This JHU/APL news release gives useful background: The LECP instrument has seen sudden increases in cosmic rays and decreases in low-energy particles, a varying scenario that has yet to settle down. Krimigis and team are saying that Voyager may be in a new region but not yet in true interstellar space.

Image: This artist’s concept shows plasma flows around NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft as it gets close to entering interstellar space. Voyager 1′s Low-Energy Charged Particle instrument detects the speed of the wind of plasma, or hot ionized gas, streaming off the sun. It detected the slowing of this wind – also known as the solar wind – to zero outward velocity in a region called the stagnation region. Scientists had expected that the solar wind would turn the corner as it felt the pressure of the interstellar magnetic field and the interstellar wind flow. But that did not happen, so scientists don’t know what to expect once Voyager actually crosses the heliopause. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

The term ‘magnetic highway’ comes up because in this region low-energy particles from inside the heliosphere are flowing out while higher-energy particles are flowing in — the Sun’s magnetic field lines are connected to interstellar magnetic field lines. While charged particles bounced in all directions before Voyager 1 entered this region, as if firmly contained by the surrounding heliosphere, they’re now much more directional. Krimigis again:

“If we were judging by the charged-particle data alone, I would have thought we were outside the heliosphere. In fact, our instrument has seen the low-energy particles taking the exit ramp toward interstellar space. But we need to look at what all the instruments are telling us and only time will tell whether our interpretations about this frontier are correct. One thing is certain – none of the theoretical models predicted any of Voyager’s observations over the past 10 years, so there is no guidance on what to expect.”

I suppose it was the ‘magnetic highway’ metaphor that brought back my night drive through the Cumberlands and all the musing about interstellar missions at a time when Voyager 2 had not yet reached Neptune (and Voyager 2, by the way, shows no signs of reaching the magnetic highway at a distance of about 15 billion kilometers from Earth). Voyager project scientist Ed Stone (Caltech), as venerable a figure as they come in the Voyager pantheon, thinks true interstellar space is a few months to a couple of years away for the farthest Voyager.

We’ll lose something priceless when the Voyagers finally go silent, but New Horizons is still robust and that gives me hope. I think we need a continuing voice from the deep dark to remind us that our nature is to explore even if human lifetimes fade to insignificance against the starry backdrop that bore us. Daily work is the thing, and to work for what Tennyson called ‘the long result’ is the best work there is, whether we’re there to see the end of the mission or not.

December 4, 2012

ASPW 2012: A Report from Huntsville

Richard Obousy, a familiar face on Centauri Dreams, is president and primary propulsion senior scientist for Icarus Interstellar, whose portfolio includes Project Icarus, the redesign of the Project Daedalus starship. Dr. Obousy is just back from the latest Advanced Space Propulsion Workshop and, as he did for the 2010 ASPW, he now offers his take on the event. Although I missed this ASPW, I’ll be back in Huntsville soon for an upcoming conference, and I heartily second what Richard has to say about that Saturn V at the US Space and Rocket Center. It’s not to be missed.

by Richard Obousy

The 2012 Advanced Space Propulsion Workshop (ASPW) was held over three days at the US Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama running from Tuesday 27th November to Thursday 29th November. The conference was sponsored by the Game Changing Development Program under NASA’s Space Technology Program and the Office of the Chief Technologist at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center.

This was the 19th cycle of the workshop, with the first workshop convening in 1990. Owing mainly to NASA budget cuts, the conference ceased being annual after the 16th workshop in April 2005.

ASPW focuses principally on early-stage propulsion research, in the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 1-2 range. Presentations were loosely grouped by topic, with subjects including Advanced Electric Propulsion, Propellantless Propulsion, Advanced Launch Systems, Nuclear Propulsion, and Micropropulsion.

Image: Saturn V model at the US Space and Rocket Center with Icarus Interstellar Directors Robert Freeland, Richard Obousy and Bill Cress on a particularly chilly Huntsville afternoon.

Icarus Interstellar had seven team members in attendance including myself and Directors Robert Freeland, Andreas Tziolas and Bill Cress, also researchers Tabitha Smith (Bifrost), Milos Stanic (Project Icarus) and Rob Adams (Project Icarus). Being a ‘virtual’ team we rarely have the chance to see each other face to face, so it was fantastic to have the opportunity to all meet up in the same room. In addition to attending the workshop, the Icarus Interstellar team also held private meetings where we were able to discuss a number of organizational and project matters.

Image: Five of the seven Icarus Interstellar team members attending ASPW. From left to right, Andreas Tziolas, Richard Obousy, Bill Cress, Milos Stanic, Rob Adams.

While the presentations are typically the foci of workshops like this, the networking value of the conference cannot be understated. We had the opportunity to expose our team and our mission to some of the most adept propulsion scientists in the country and solicit feedback and make new friends. I had the privilege of attending the 2010 ASPW, and back then I found that few had heard of Icarus Interstellar. However this year our work was well known, and we even noted several citations to our work from other conference presenters. For me, the fact that our hard (and volunteer) work is getting us noticed within this community speaks volumes regarding the dedication and commitment of the team.

There were a number of highlights of the event for me. One was having the pleasure to engage with Professor Friedwardt Winterberg, an American theoretical physicist who was the creative force behind the Daedalus engine. He collaborated with Alan Bond and the Project Daedalus team back in the 1970s to create the “Winterberg Daedalus Class Magnetic Compression Reaction Chamber”, an internal/external hybrid inertial confinement fusion pulsed propulsion design. Although this design is now known to have some fundamental flaws, it was arguably the most visionary interstellar propulsion design in its time.

Image: Andreas Tziolas and Richard Obousy talking with the inspiration for the Daedalus engine, physicist Friedwardt Winterberg.

Another highlight for me was a tour of the Marshall Space Flight Center situated in the Army’s Redstone Arsenal base. There I was thrilled to see a Marx generator being prepared for study of plasma instabilities under fusion conditions. The device is able to discharge a 1 TW pulse after charging a large number of capacitor banks.

One final highlight was the US Space and Rocket Center just a short walk from the ASPW workshop. The museum housed one of the three remaining Saturn V rockets on public display and was designated a national historic landmark by the National Park Service in 1987. Seeing the rocket for me is always a bittersweet experience. It’s a reminder of a tremendous era for our space exploration, when Americans came together to undertake one of the most profound missions of exploration in all of history. It’s also a sad reminder that it’s been almost forty years since we last stepped foot on the moon, with no firm plans to return in the foreseeable future. I hope that workshops like ASPW cement the foundations for a brave new era in space exploration, one that I live to see.

December 3, 2012

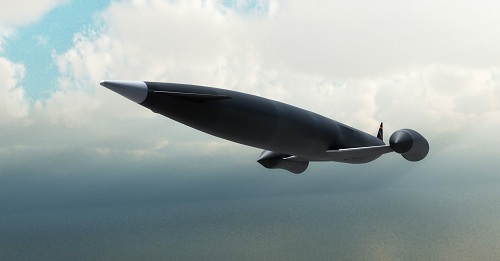

Skylon: Promising Tests of the SABRE Engine

The news from Reaction Engines Ltd. about its air-breathing rocket engine SABRE is interesting not only for its implications in near-term space development, but also for its pedigree. Reaction Engines grew out of British work on a single-stage-to-orbit concept called HOTOL ((Horizontal Take-Off and Landing) that was being developed by Rolls Royce and British Aerospace in the 1980s. Initially backed by the British government, HOTOL lost its funding in 1988, prompting Alan Bond’s decision to form the new company, which would continue the work with private funds.

The name Alan Bond should ring many bells for Centauri Dreams readers. Bond was a key player in and leading author of the report on the British Interplanetary Society’s Project Daedalus, the ambitious 1970s attempt to design a starship based on fusion propulsion. One thing the extensive Daedalus effort made clear was that a future attempt to reach the stars could only take place within the context of a Solar System-wide infrastructure, one that would have the ability to mine the atmospheres of the outer planets for the needed helium-3 and other resources. It’s no surprise, then, that Bond’s attention should now be on that infrastructure and how to build it.

Image: Reaction Engines’ Alan Bond, whose company’s recent tests promise single-stage-to-orbit at drastically reduced costs.

For one craft SABRE is intended to power is a reusable spaceplane called Skylon that would reach orbit in a single stage, lowering the cost per kilogram of payload substantially, perhaps to as little as $1000 or less. As presented by Reaction Engines, Skylon is anything but another Space Shuttle. It would take off from a conventional runway, accelerating to Mach 5.4 at 26 kilometers altitude before switching its engines over to internal liquid oxygen mode to take the craft to low-Earth orbit.

The project’s backers say they can carry up to 15 tonnes into orbit aboard the unpiloted craft, a payload that could also, using a habitation module, be comprised of up to 30 astronauts in a single launch vehicle. Upon delivery of its cargo or complement of astronauts, the vehicle would re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere and land back at the runway, undergoing inspection and any needed maintenance before, within two days, being returned to the flight line. If Skylon can live up to this ambitious scenario, then it will have given us what the Space Shuttle promised — reusability with quick turnaround — in a far more flexible and much less expensive design.

Much comes down, as you can imagine, to the SABRE engine. The acronym stands for Synergistic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine, a design that combines a turbo-compressor with an air pre-cooler that at high speeds can cool hot compressed air that will then be fed into the rocket combustion chamber, where liquid hydrogen will form the other part of the mixture to be ignited. The pre-cooler technology is the key. It allows the incoming airstream to be cooled from over 1000 degrees C to minus 150 C in less than 1/100th of a second without any frost blockage.

SABRE thus works initially in air-breathing mode, using the atmosphere as its source of oxygen for burning with the liquid hydrogen in the rocket combustion chamber. Once above the atmosphere, the craft makes the transition to conventional on-board liquid oxygen. The dual approach means that a vehicle like Sylon could save over 250 tons of on-board oxidant — no huge first stage that has to be jettisoned as soon as the oxidant is used up . The pre-cooler work is critical because in its air-breathing mode, SABRE has to compress the air to 140 atmospheres before injecting it into the combustion chamber. Without the new pre-cooler technology, that would raise the air temperatures high enough to melt engine materials.

Recent tests on SABRE involving over 100 test runs at the Reaction Engines facility in Oxfordshire have demonstrated the workability of the concept in the eyes of the European Space Agency, which has been funding part of the work. This Reaction Engines news release quotes ESA’s evaluation: “The pre-cooler test objectives have all been successfully met and ESA are satisfied that the tests demonstrate the technology required for the SABRE engine development.” The successful pre-cooler testing should allow the release of additional funding for the Skylon project from the British government according to an April 2011 agreement.

As for Alan Bond, he’s convinced Reaction Engines has proven its point:

“These successful tests represent a fundamental breakthrough in propulsion technology. Reaction Engines’ lightweight heat exchangers are going to force a radical re-think of the design of the underlying thermodynamic cycles of aerospace engines. These new cycles will open up completely different operational characteristics such as high Mach cruise and low cost, re-usable space access, as the European Space Agency’s validation of Reaction Engines’ SABRE engine has confirmed. The REL team has been trying to solve this problem for over 30 years and we’ve finally done it. Innovation doesn’t happen overnight. Independent experts have confirmed that the full engine can now be demonstrated. The SABRE engine has the potential to revolutionise our lives in the 21st century in the way the jet engine did in the 20th Century. This is the proudest moment of my life.”

You have to imagine that amidst that pride there is a bit of the old Daedalus excitement lingering in Bond’s work with Skylon, given that lowering launch costs by more than ten times is a necessary first step toward the infrastructure he foresaw as far back as the 1970s, when the Daedalus designers crunched numbers and sketched ideas at the Mason’s Arms pub on Maddox Street in London. But while Daedalus was speculative and, for its time, science fictional in its ambitions, Reaction Engines is now working with a design that could have a payoff in the not so distant future. We build out an infrastructure one step at a time, but the first step is to get into position. Cheap access to low-Earth orbit opens up scenarios that may one day take us far beyond our planet.

Paul Gilster's Blog

- Paul Gilster's profile

- 7 followers