Paul Gilster's Blog, page 156

March 28, 2016

Saturn’s Moons: A Question of Age

Some years back at a Princeton conference I had the pleasure of hearing Richard Gott discussing the age of Saturn’s rings. Gott is the author of, in addition to much else, Time Travel in Einstein’s Universe (Houghton Mifflin, 2001). I admit the question of Saturn’s rings had never occurred to me, my assumption being that the rings formed not long after the formation of the planet. But of course there is no reason why this should be, and a number of reasons why it should not. How long, for instance, does it take moons to collide with each other, contributing debris to a growing ring system? And are such collisions the only way a ring system can form?

With all this in mind, I was interested in a new paper that a number of readers referenced in emails. Lead author Matija Ćuk (SETI Institute), working with Luke Dones and David Nesvorný (both at SwRI), offers up the possibility that the inner moons of Saturn and possibly the rings were actually formed much later than we would expect. In fact, they may be positively recent in astronomical terms, having formed during or not so long after the era of the dinosaurs.

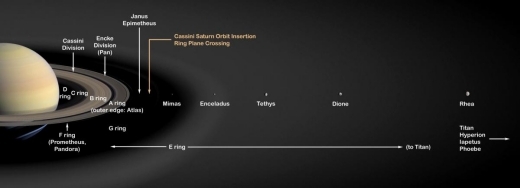

Image: The new paper finds that Saturn’s moon Rhea and all other moons and rings closer to Saturn may be only 100 million years old. Outer satellites (not pictured here), including Saturn’s largest moon Titan, are probably as old as the planet itself. Credit: NASA/JPL.

The work involves the moon Rhea and all the other moons and rings closer in to Saturn. The outer satellites, including Titan, are still thought to be as old as the planet itself. But using numerical simulations, the trio explored the tidal effects that should be causing the inner moons of Saturn to spiral out to larger orbital radii. Each of the moons would experience different growth in its orbit, which would occasionally produce orbital resonances. Such effects, in a system crowded with moons, can cause orbits to diverge from their original plane.

The team’s simulations homed in on a hypothetical 3:2 resonance in the past between the moons Tethys and Dione, along with a 5:3 resonance crossing between Dione and Rhea. Remember what happens in such a resonance: A moon’s orbital period becomes a fraction — one-half, or two-thirds, for example — of another moon’s orbital period. The paper notes that the current Tethys/Dione and Dione/Rhea orbital period ratios are just above 2/3 and 3/5. Does this mean these resonances were crossed at some point in the past?

Perhaps not, for interestingly, the 3:2 resonance crossing should have led to an excitation in the orbital inclinations of both Tethys and Dione, something that is not observed in their current orbits. The 5:3 resonance between Dione and Rhea, according to the authors, probably did happen, to be followed by a previously unknown Tethys-Dione resonance. The combination can explain the current inclinations of both Tethys and Rhea. Quoting from the paper:

We can therefore state that Tethys and Dione evolved tidally by only a modest amount over their lifetimes, which is only about a quarter of the tidal evolution envisaged in Murray & Dermott (1999). There are two possible interpretations: either tidal evolution of Saturn’s moons has been very slow, or Saturn’s mid-sized moons are significantly younger than the Solar System. While both interpretations are consistent with the lack of the past Tethys-Dione resonance, we favor the idea that the moons are young, possibly as young as 100 Myr… The Trojan moons of Tethys and Dione that share their inclinations must have formed even more recently, after their passage through the secular resonance.

The inclination of the orbits of the moons in question, in other words, should have been altered more than they have been by gravitational interactions, an indication that orbital resonances have been few. And that, the authors conclude, is evidence they must have formed recently. That leads directly to the question of how the inner moons formed. Says Ćuk:

“Our best guess is that Saturn had a similar collection of moons before, but their orbits were disturbed by a special kind of orbital resonance involving Saturn’s motion around the Sun. Eventually, the orbits of neighboring moons crossed, and these objects collided. From this rubble, the present set of moons and rings formed.”

All this has implications for our view of Enceladus, which experiences intense tidal heating that is incompatible with a slowly evolving system. The presence of an internal ocean gives high astrobiological interest to this moon, but according to these researchers, Enceladus, Mimas and the rings could have formed at the same epoch as Dione and Rhea or be even younger (the authors intend to explore the tidal evolution of Mimas and Enceladus in future work). Would an Enceladus as young as the Cretaceous Period on Earth have had time to develop life? It’s a question we can clarify with future missions designed to fly through the Enceladus plume.

The paper is Ćuk et al., “Dynamical Evidence for a Late Formation of Saturn’s Moons,” to be published by The Astrophysical Journal (preprint). A SETI Institute news release is also available.

March 25, 2016

Thirteen to Centaurus

J. G. Ballard (1930-2009) emerged as one of the leading figures in 20th Century science fiction. His fascination with inner as opposed to ‘outer’ space infused his characters and landscapes with a touch of the surreal, taking the fiction of the space age into deeply psychological realms. Christopher Phoenix here looks at the question of centuries-long journeys to the stars, with reference to a Ballard story in which a crew copes with isolation on what appears to be an interstellar mission. What we learn about ship and crew informs the broader discussion: If it takes more than a single generation to make an interstellar crossing, what can we do to keep our crew functional? And is there such a thing as happiness under these constraints?

By Christopher Phoenix

A few months back, Centauri Dreams ran Gregory Benford’s review of Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel Aurora. After reading that review and the discussion that followed, I began thinking about fiction that explores how starflight might fail. I hope that we will reach the stars someday, but it is always interesting to step back and explore the reasons why interstellar flight might not be an inevitable part of our future.

Perhaps due to science fiction’s roots in the pulp magazines of the 20s and 30s, many SF stories show an unwavering faith in humanity’s ability to overcome any obstacle. In most science fiction, it is a foregone conclusion that humanity will reach the stars. Space opera stories expect that the reader will accept the existence of a human interstellar civilization from the very first pages. Stories that dispute this assumption are much rarer.

One such story is James G. Ballard’s “Thirteen to Centaurus”. This short story takes place within a mysterious habitat known only as “The Station” by its thirteen-person crew. For generations, they have lived within the confines of the Station’s three decks. At the beginning of the story, one of the teenage members of the crew, a boy named Abel, suffers recurring nightmares of a burning disk. The only person who can tell him the meaning of these visions is Dr. Francis, the Station’s doctor, who lives alone on another deck.

Dr. Francis tells Abel that the Station is actually a starship traveling to Alpha Centauri and explains that the burning disk is a repressed genetic memory of the Sun he has never seen. When Abel asks Dr. Francis when they will arrive, he explains that the Station is a multi-generational spaceship. None of the current generation will live to see planetfall. Dr. Francis tells Abel that the rest of the crew cannot know this truth, as otherwise they will never be happy in their confined artificial world.

Soon, however, the story takes another twist. It turns out that Dr. Francis is lying, and the Station is in fact an Earth-bound experiment designed to test whether humans can survive a century-long flight to Alpha Centauri. In truth, Dr. Francis is one of the researchers posing as a member of the crew, sent to secretly observe them from among their midst. The Station’s planners believed that humans could not survive such a trip knowing that they are condemned to live their whole lives in a confined spacecraft. Generations of crew will never see the Earth where they came from or live long enough to reach their destination. To solve this problem, the researchers use hypnotic suggestion to eradicate memories of Earth and make the crew accept the Station as the only world that exists.

Image: Science fiction writer J. G. Ballard.

As the story continues, we see Dr. Francis leave the habitat to meet with his colleagues. To his horror, his superiors tell him that the project must be shut down due to lack of public support. They ask Dr. Francis how to transition the crew from their isolated life in the station to the outside world. Hoping to convince them to continue the simulation, Dr. Francis insists that the crew cannot survive having their worldview shattered in this way. The only way to humanely end the project is to stop the crew from having children and wait for the current generation to die out. His superiors are so desperate to end the project that they agree to take this extreme course of action.

As the experiment is gradually shut down, Abel begins to ask Dr. Francis awkward questions about the Station. Dr. Francis’s clumsy attempts to hide the true nature of the Station only seed Abel’s mind with further doubts. In a more disturbing turn, Abel begins showing an unhealthy interest in performing psychological experiments of his own devising on the other members of the crew and even Dr. Francis himself.

Unwilling to accept the termination of the project, Dr. Francis finally decides to seal himself inside the dome to complete the imaginary trip to Centaurus with the crew, knowing that no one will dare enter the habitat to remove him. Once within the habitat, however, he realizes just how monotonous the crew’s life really is. Unfortunately, he dares not leave, since entering the habitat without permission carries a mandatory 20 year prison sentence. At this point, Abel takes the opportunity to turn the tables on Dr. Francis, forcing him to participate in his psychological experiments as a subject. Abel has begun to run the Station like a minor tyrant.

In the end, Dr. Francis finds a hole in the outer dome through which the previous captain and Abel have observed supplies being brought into the habitat. He realizes that the captain knew the truth and choose to stay in the dome. Before he died, he told Abel, and Abel has chosen to feign ignorance and stay within the station so that he can be the de facto ruler of this tiny world.

Trapped in a Tin Can

Ballard questions whether humans can adapt to life in a multi-generational starship. In his story, the designers of the Station believe that people would find their life in such a ship so limited compared to life on a planet that they could never be happy. Their solution is to eradicate the crew’s awareness of any other possible existence. This one idea drives much of the design of the Station.

The Station’s planners attempt to achieve this goal by using hypnosis and subliminal suggestion. The crew only believe themselves to be happy because they are conditioned to do so. Subliminal messages have been embedded in educational tapes that the crew are required to listen to at regular intervals. The message that there is no life beyond the Station is constantly reinforced by these tapes. In addition to this regular conditioning, every aspect of the crew’s’ life is scheduled and controlled. They have no freedom of thought or action. Since they are supposed to believe that there is no life beyond the Station, the crew has no access to the books, art, and culture of Earth. Even though this sort of highly effective “mind control” doesn’t really exist outside of science fiction, Ballard presents a stark view of what life could be like in a multi-generational starship. Even if this scheme could work, it would only be at great psychological cost to generations of crew.

Image: “Thirteen to Centaurus” can be found in, among other places, The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard (Norton, 2010).

Ballard is not alone in his opinion. If you mention multigenerational spaceflight, many people will tell you that it is incredibly unfair to condemn generations of people to life aboard a ship in interstellar space. The idea that it will be impossible to be truly happy in an artificial world that you cannot escape drives much of the criticism of multi-generational spaceflight. Ballard has clearly touched on a tender nerve.

In the story, however, Dr. Francis finds that not all is as it seems. After sealing himself in the simulator, he discovers that the late captain and the teenage Abel both knew that they were in a habitat on Earth, and yet they chose to remain. For Abel, staying in the habitat gives him the opportunity to dominate the other members of the crew and force them to participate in his psychological experiments.

Here, Ballard raises another disturbing question. In an enclosed habitat, might one ambitious individual or small elite group seek to control the rest of the crew? Aboard a starship in interstellar space, there would be no external checks on oppressive leadership, or any way to escape it. Because of this, choosing the right form of governance would be vital for a generation ship. Unfortunately for the inhabitants of the Station, the researchers put all their trust in their mind-control methods. They did not have any means to check someone, like Abel, who broke beyond their mental blocks.

This story reminds us that we must plan for the social and psychological factors of multi-generational trips as carefully as we do for the purely mechanical ones such as life support, radiation shielding, and propulsion systems.

Losing Enthusiasm

In Ballard’s story, the people running the century-long simulation decide to shut the project down midway. When the project was started, humanity was attempting to colonize the Moon and Mars. The public was enthusiastic about space travel, and many people believed that they would eventually build interstellar ships. So, it was decided to test social conditions on such a trip even before the technology to build a starship or a self-sustaining habitat was available.

When the story takes place, the Lunar and Martian colonies have failed. The public is no longer interested in space travel. Furthermore, they have begun to question the ethics of sealing generations of people in the simulator and observing their every move. Almost everyone wants to end the project.

Ballard suggests that humans will have difficulty maintaining focus and enthusiasm long enough to complete a prolonged effort like developing interstellar travel, which could take centuries. A case can be made for this argument by just looking at our history. Even though we reached the Moon, politicians chose to cancel the Apollo program. In the years that have followed, the numerous plans to return to the Moon and/or go to Mars have been not been carried out. Astronauts have not even ventured beyond low-Earth orbit since the Apollo missions.

Currently we don’t have a replacement for the space shuttle, or a coherent plan of what to do to follow up on our current space probe missions and the ISS. It often seems that ambitious plans to explore space are more likely to fail because of lack of political support than technological obstacles. Human civilization will need to develop a much longer planning horizon than we currently have to maintain the political will needed to develop interstellar travel.

Our lessons come from the journey, not the destination…

Ballard raises many interesting issues in this story. However, despite the melancholy ending of “Thirteen to Centaurus”, I’m still quite optimistic about the future of multigenerational space travel. Personally, I believe that it’s possible for humans to be happy aboard a generation ship in deep space, even knowing that they will not live to see their destination.

When a group of people set out on an interstellar journey that only their descendants will complete, the ship will become their home as well as the home of the generations between launch and planetfall. Therefore, I propose it is more important to plan for the interstellar journey than to fixate on the destination. We must plan the voyage so that the people who are born, live, and die on the spaceship have the opportunity to live full lives.

Image: Ballard’s work occasionally made it to other media, most notably in the 1987 Spielberg film Empire of the Sun. This is a shot from a TV adaptation of “Thirteen to Centaurus,” as presented on Out of the Unknown, a BBC science fiction anthology series broadcast between 1966 and 1971. Starring were Donald Houston, John Abineri, Robert James and Noel Johnston.

The common objection to multi-generational spaceflight is that the crew will not be happy with their lives aboard the ship, or that they will even “go mad” from the psychological strain. Why should the crew go mad on a generation ship? Ballard’s story suggests two main reasons. One is lack of space and forced lifelong contact with only a few people, and no way to escape someone you do not wish to know. The other is a feeling of deprivation from being born on a starship, not on a planet of your own.

The first problem can be solved by simply sending a more reasonably sized crew. In Ballard’s story, the Station’s population is a scant thirteen, not nearly enough! So far, most population size studies for starships have focused on genetic factors or maintaining specialized skill sets, not on social or psychological needs. I’ll make a stab and say that a crew size of at least a few hundred people, similar to a typical Medieval village, will provide ample choice in human contacts.

Earlier, I touched upon the issue of leadership. Since there will be no possible external checks on dictatorial behavior within an isolated starship, we must choose the right form of governance at the beginning of the trip and place what safeguards we can to avoid abuses of power. While a certain amount of centralized authority will be necessary to respond to emergencies, the people responsible for the day-to-day life of the crew should not be autocratic or oppressive. The leadership must be flexible enough to accept any changes that will become necessary during the course of the trip. This suggests the traditional military-style command structure used on all crewed spaceflights since the Cold War will not work for multigenerational spaceflight.

But what about lack of space? In “Thirteen to Centaurus”, the crew was confined to only three decks. I don’t think any crew could thrive, or even survive, in such cramped conditions. We must provide the crew with sufficient space. I am of the opinion that a sufficiently spacious ship-style interior could work for people who have adapted to life in space habitats. Garden spaces can be incorporated into the interior design, creating a more naturalistic environment, unlike the harsh mechanized interiors described in many science fiction stories. But it is also possible to create a starship large enough to contain an open Earth-like landscape.

The largest generation ship concepts are designed like traveling O’Niell colonies. Such “world-ships” can contain an Earth-like landscape on their interior, including an artificial sun, creating an environment almost like an inside-out planet in miniature. The main problem with such a scheme is constructing and launching such a gigantic structure, but such a craft can offer an Earth-like existence during a long flight.

But will the crew feel deprived living their entire lives away from any planet, as the researchers in Ballard’s story believe? I think Ballard misses the mark here. We neither choose nor tend to question the environment we are born into. The crew of an interstellar ship would accept their environment as normal, just as countless people throughout history have accepted their unique environment on Earth as “normal”.

To modern first-world people, the idea of living and dying within a relatively small area like a generation ship seems impossible, but the amount of mobility available to us is unusual compared to the lifestyles of earlier people. It is even possible that people who have lived their entire lives in space will think of living on a planet as something strange or even unpleasant. They may wonder how we put up with weather we don’t control, or a constant gravitational acceleration we can’t modify to our preference just by going to another deck. On the other hand, things we see as strange and maybe even frightening, like relying for our very survival on ship systems continuing to function, will be accepted as normal by them.

Only time will tell if human civilization can muster the energy and will to send starships to the potentially habitable exoplanets we discover around nearby stars. But if we do, I firmly believe that people will be able to live happily aboard those ships. Even though these voyages will realistically take centuries to complete, humans possess the flexibility and resilience to adapt to life in almost any environment. Certainly, the culture aboard such a ship would not be anything like modern life on Earth, but that does not mean that such a culture could not be as complex and fulfilling as any throughout human history.

March 24, 2016

Planets in the Process of Formation

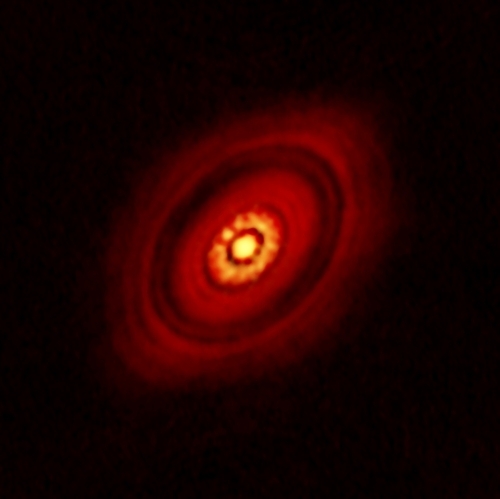

Back in 2014, astronomers used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to produce high-resolution images of the planet-forming disk around the Sun-like star HL Tau, about 450 light years away in the constellation Taurus. The images were striking, showing bright and dark rings with gaps, suggesting a protoplanetary disk. Scientists believed the gaps in the disk were caused by planets sweeping out their orbits.

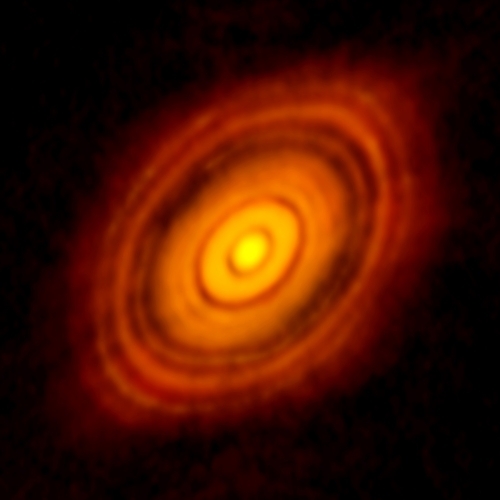

All this was apparent confirmation of planet formation theories, but also a bit of a surprise given the age of the star, a scant million years, making this a young system indeed. Here is the ALMA image, along with the caption that ran with the original release of the story from NRAO.

Image: The young star HL Tau and its protoplanetary disk. This image of planet formation reveals multiple rings and gaps that herald the presence of emerging planets as they sweep their orbits clear of dust and gas. Credit: ALMA (NRAO/ESO/NAOJ); C. Brogan, B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF).

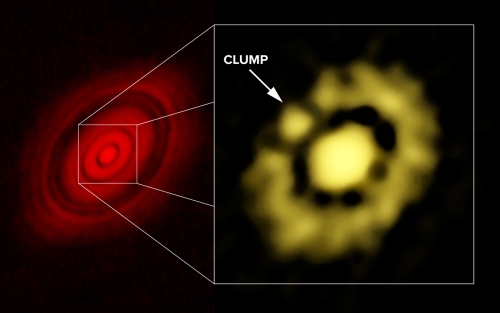

Now we have further work on HL Tau, this time based on data from the Very Large Array (VLA). As opposed to the ALMA work, which showed details in the outer portions of the disk only, the VLA findings, working at longer wavelengths, get us into the inner portions of the disk. At these wavelengths (7.0 mm), the dust emission from the inner disk can be penetrated.

What we see is what this NRAO news release calls ‘a distinct clump of dust’ in the inner disk region, one that contains from 3 to 8 times the mass of the Earth. The researchers believe they are looking at the earliest stage in the formation of protoplanets, seen in the image below for the first time. Not a ‘planet,’ mind you, but a ‘clump of dust.’

Image: ALMA image of HL Tau at left; VLA image, showing clump of dust, at right.

Credit: Carrasco-Gonzalez, et al.; Bill Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSF.

“This is an important discovery, because we have not yet been able to observe most stages in the process of planet formation,” said Carlos Carrasco-Gonzalez from the Institute of Radio Astronomy and Astrophysics (IRyA) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). “This is quite different from the case of star formation, where, in different objects, we have seen stars in different stages of their life cycle. With planets, we haven’t been so fortunate, so getting a look at this very early stage in planet formation is extremely valuable,” he added.

The inner region of the disk, thought to contain grains as large as one centimeter in diameter, is where Earth-like planets would be likely to form as aggregations of dust accumulate and draw in material, eventually gathering the mass to form the planetesimals that become planets. The paper on the VLA work argues that we are looking not at planets that have already formed in gaps in the dusty disk, but at the very earliest stages of future planet formation:

We propose a scenario in which the HL Tau disk may have not formed planets yet, but rather is in an initial stage of planet formation. Instead of being caused by (proto)planets, the dense rings could have been formed by an alternative mechanism. Our 7.0 mm data suggest that the inner rings are very dense and massive, and then, they can be gravitationally unstable and fragment. It is then possible that the formation of these rings result in the formation of dense clumps within them like the one possibly detected in our 7.0 mm image. These clumps are very likely to grow in mass by accreting from their surroundings, and then they possibly represent the earliest stages of protoplanets. In this scenario, the concentric holes observed by ALMA and VLA would not be interpreted as a consequence of the presence of massive (proto)planets. Instead, planets may be just starting to form in the bright dense rings of the HL Tau disk.

The following image pulls the ALMA and VLA work together.

Image: Combined ALMA/VLA image of HL Tau. Credit: Carrasco-Gonzalez, et al.; Bill Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSF.

The paper is Gonzalez et al., “The VLA view of the HL Tau Disk – Disk Mass, Grain Evolution, and Early Planet Formation,” accepted by Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint).

March 23, 2016

Gravity, Impartiality & the Media

Marc Millis is once again in the media, this time interviewed by a BBC crew in a show about controlling gravity. The impetus is an undertaking I described in the first chapter of Frontiers of Propulsion Science, Project Greenglow. The former head of NASA’s Breakthrough Propulsion Physics project and founding architect of the Tau Zero Foundation, as well as co-editor with Eric Davis of the aforesaid book, Millis has some thoughts on how we discuss these matters in the media, and offers clarifications on how work on futuristic technologies should proceed.

by Marc Millis

A BBC ‘Horizons’ episode will air next Wednesday, March 23 (8pm UK) about the Quest for Gravity Control. The show features, among other things, an interview with myself about my related work during NASA’s Breakthrough Propulsion Physics project and thereafter with the Tau Zero Foundation. Quoting from an advertisement for the show, Project Greenglow – The Quest for Gravity Control:

This is the story of an extraordinary scientific adventure – the attempt to control gravity. For centuries, the precise workings of gravity have confounded the greatest scientific minds – from Newton to Faraday and Einstein – and the idea of controlling gravity has been seen as little more than a fanciful dream. Yet in the mid 1990s, UK defence manufacturer BAE Systems began a ground-breaking project, code-named Greenglow, which set about turning science fiction into reality. On the other side of the Atlantic, NASA was simultaneously running its own Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Project. It was concerned with potential space applications of new physics, including concepts like ‘faster-than-light travel’ and ‘warp drives’.

With such a provocative topic, it can be difficult to extract the realities between the more entertaining extremes of delusional crackpots and pedantic prudes. We’ve not yet seen the episode to know what is, or is not, covered. For those interested in the more substantive realities – at least to the level of our own perceptions – here is a short status report.

First, there are several lines of inquiry in general physics. This includes Einstein’s theory, which describes gravity in terms of warped spacetime; high-energy particle experiments that explore the unification of all the fundamental forces at higher energies; and cosmological observations on the role of gravitation and quantum phenomena on the formation of the universe. Such investigations are aimed at understanding nature for its own sake, rather than for the ambition of controlling gravitation.

One example of applying this knowledge to the challenge of controlling gravity goes back to the early 1960’s with Robert L. Forward’s “Dipole Gravitational Field Generator ” (Am. J. Phys., Vol. 31, 1963, pp. 166-170). In this and subsequent works by others, it has been shown that spacetime can be warped to produce “designer” gravitational fields. Such warps require enormous energy densities and/or stresses/pressures of either moving matter, extreme electromagnetic fields, or specially modified quantum vacuum energy. This has not yet led to any practicable devices.

When one shifts the focus from general physics to a utilitarian challenge (say, controlling gravitation for propulsion or for zero-gravity recreational rooms), two important points come into play:

Having a desired application can taint one’s objectivity, since there is a desire for the results to turn out a particular way. This makes it harder to conduct the work with the rigor and impartiality needed to get reliable results. It is too easy to become either overly eager or pedantic. Hence, a higher degree of self-discipline is required when conducting application-specific research.

By focusing on an application instead of for general knowledge, new pathways toward solving the lingering unknowns of science are created. In the first step of the scientific method, where one defines the problem to be solved, how that problem is defined then casts a unique perspective from which data will be collected and interpreted. It changes the way to look at the problem.

In 2009, Eric Davis and myself, working with over a dozen contributing authors, compiled a book about the various approaches for controlling gravitation and faster-than-light flight. By contrasting the make-or-break issues of these goals with known physics, the book identifies where next to concentrate research. It is still too soon to know if such breakthroughs will ever be achievable, but such application-specific research can now commence. Chapters 3 through 13 cover the topic of controlling gravity for space drives, while chapters 14 through 16 address faster-than-light flight:

– M. G. Millis and E. W. Davis (eds.), Frontiers of Propulsion Science, Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics, Vol. 227, AIAA Press, Reston, VA, 2009, 2nd printing 2012.

Subsequent condensations have been published as:

– M. G. Millis (2012), “Space Drive Physics, Introduction & Next Steps,” JBIS, Vol. 65, pp. 264-277. From this, it appears that the next line of inquiry deals with the nature of inertial frames. Inertial frames are the reference frames upon which the laws of motion and the conservation laws are defined, yet it is still unknown what causes inertial frames to exist and if they have any deeper properties that might prove useful.

– E. W. Davis (2013), “Faster-Than-Light Space Warps, Status and Next Steps,” JBIS, Vol. 66, pp. 68-84. From this, it appears that the next lines of inquiry deal with the structure of the quantum vacuum in the context of warped spacetime. This includes closer examinations of the technological approaches to affect the quantum vacuum that might produce space warps.

While general physics has been making incremental progress to our understanding of gravitation, the other fundamental forces, and spacetime for centuries, research aimed at controlling gravitation for practical purposes is still in its infancy. In addition to the challenges of deciphering nature, the desire for a positive result makes it difficult to conduct the research with the impartiality needed to produce rigorous results. With a healthy blend of imagination, skepticism, and reason, progress will be made. One never knows how a media project will turn out, but my hope is that “Project Greenglow – The Quest for Gravity Control” will reflect these values.

March 22, 2016

TVIW 2016: Homo Stellaris Working Track

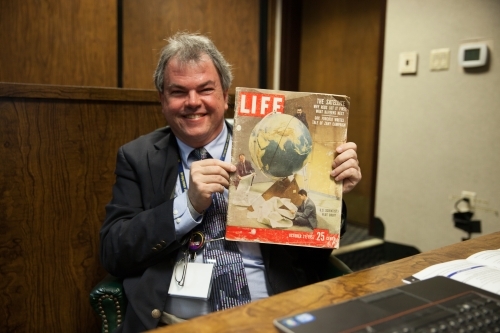

Herewith the first of several reports on the recent Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop; more next week. It comes from Doug Loss, who was a participant in the Homo Stellaris working track I had hoped to attend before illness changed my plans. An experienced network and IT security administrator, Doug attended and eventually organized The Asimov Seminar from 1977 until the early 2000s, a yearly, four-day-long retreat at a conference center in upstate New York. Isaac Asimov, the noted science fiction author, was the star of the Seminar and its main draw until his death in 1992. Each year the Seminar would explore a different topic having to do with the future of human society, with Seminar attendees assuming roles that would allow them to examine the questions associated with that year’s topic on a personal basis. TVIW is likewise following a highly interactive workshop strategy, as Doug’s report attests. The photos below come from New York photojournalist Joey O’Loughlin, and are used with permission.

By Douglas Loss

The Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop took place from February 28 through March 1 in Chattanooga, Tennessee, a very pleasant place to be. On both Monday and Tuesday the mornings were taken up by multiple plenary talks, primarily on technical topics, with most dealing with propulsion possibilities for interstellar flight.

Two notable exceptions were the talks by General Steven Kwast, commander and president of Air University on Maxwell Air Force Base and by Dr. James Schwartz, professor of philosophy at Wichita State University. Both of these talks seemed to engender some “push-back” from various participants.

General Kwast’s talk was titled, “Invited Remarks Concerning America’s Far Future in Deep Space.” The general talked about what it means to have legal authority to enforce behaviors, and how this might apply in interplanetary as well as interstellar societies. His talk was clearly from an American perspective, which seemed to create some tension in some of the participants.

Image: Gathering in Chattanooga, TVIW meets in a plenary session. Science fiction writer Oz Monroe is in the foreground, and Greg and Jim Benford are just visible in the front row. Credit: Joey O’Loughlin.

Dr. Schwartz’s talk was titled, “Conceptual Filters in Space Exploration: Rethinking the Rationale for Planetary Protection.” The questions he posed were all related to the value of keeping extraterrestrial environments pristine, free from exploitation or any use. It is generally assumed that if life is found on an extraterrestrial body, that body should be enjoined from development at least until the life-forms have been studied thoroughly. Dr. Schwartz asked, is life on a body the only reason we should consider enjoining development of that body? Might there be other, non-vital, reasons for doing so? If so, what might these be, and who should decide? The possibility of removing sources of extraterrestrial resources from exploitability for philosophical reasons also created some tension.

Image: The assembled TVIW 2016 group. Credit: Joey O’Loughlin.

Both of these talks related directly to the Homo Stellaris working track, which was given the task of considering the biological, psychological, and sociological implications of interstellar travel. In our work sessions we made some assumptions to allow us a base to work from. We assumed that we would look at what could and should be done in the next 50-100 years. We further assumed that we were starting from the current technological and sociological baselines.

We asked ourselves what historical analogies might inform our thinking, as a way in which humanity might expand to the stars as a matter of course. The best analogy we thought of was the Polynesian expansion across the Pacific Ocean, where small groups moved from one island to another, stopping to colonize any useful island found and then the population of that island expanding on toward other islands as their island was fully colonized.

We decided that this kind of expansion might be needed in space, since we are not currently able to create a closed biosphere, or even one that will be stable for decades or centuries. The expansion we envisioned would be to habitats gradually further and further from Earth, where the possibility of rescue or large-scale repair/replacement of materials would be less and less possible. As these habitats would be created, we would learn how to improve the biospheres, gradually having them be self-sufficient for very long periods or even indefinitely.

Image: TVIW chairman Les Johnson introducing this year’s workshop. Credit: Joey O’Loughlin.

We also decided that it was important to send one or more FOCAL missions out to roughly 550 AU, to use the solar gravitational lensing technique to directly image extra-solar planets that might be prime targets for interstellar colonization. As humans are primarily visual animals, being able to see the planets would provide a much greater possibility of a positive attempt to travel to them [see Catching Up with FOCAL for background].

Finally, within the 50-100 year timeframe we decided that it should be possible to send a one-way exploration mission to a promising extra-solar planet. This mission would be comprised of roughly 100 participants, in long-term suspended animation (we reviewed the current state of the art and it seemed likely that this could be feasible within the timeframe). At any time, from 5-15 participants would be awake and monitoring the ship; the shifts would be perhaps a year long, with membership overlapping so there would be no large-scale transition from one shift to another.

Image: A quiet moment and a phone call. Interstellar researcher Philip Lubin. Credit: Joey O’Loughlin.

When the ship reached its destination, the participants would set up their habitat, preferably on the planet directly. They would live out their lives exploring the planet and transmitting their discoveries back to Earth. This mission would provide a “proof of concept” for human society, which we hoped would be even more incentive to build and launch a generation ship to colonize the planet. With some luck, the colonization ship would reach the planet before the members of the exploration mission had all died. We did anticipate the exploration mission members would have families to carry on the mission.

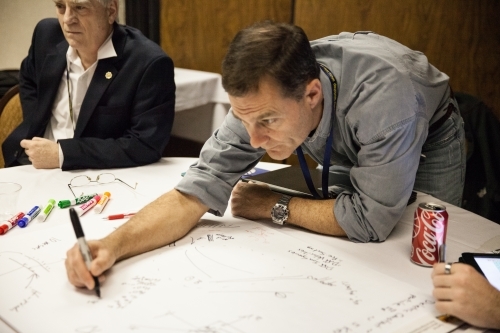

Image: A working track in progress. Marc Millis (left), Jim French (standing), Leigh Boros and Michael LaMontagne. This photo comes from the Space Solar Power track; unfortunately, Joey didn’t have any photos of the Homo Stellaris track. Credit: Joey O’Loughlin.

We didn’t extend our thoughts beyond that period, although we did discuss many of the biological, psychological, and sociological pitfalls that might occur.

We saw a robust interplanetary civilization as a prerequisite to any serious interstellar colonization attempts, as the effort to build and launch such a mission seemed very unlikely to be acceptable to any solely terrestrial group, whether commercial, governmental, religious, academic, or any other type.

Image: TVIW co-founder Robert Kennedy. Credit: Joey O’Loughlin.

There was little coordination or cross-fertilization among the working tracks, so the other groups (Worldship, Space Solar Power, and Space Mining) were quite likely starting from different assumptions than Homo Stellaris was using. This was unfortunate but probably unavoidable given the short period of time available.

Image: Icarus Interstellar’s Robert Freeland at work. Workshop track sessions were lively and intense. Credit: Joey O’Loughlin.

Overall, the workshop was very enjoyable and provided some valuable discussions on just how interstellar travel might be promoted, developed and substantiated in the real world and the reasonably near future. We look forward to the next Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop in 2017!

March 18, 2016

Making Centauri Dreams Reality, Virtually

I often think about virtual reality and the prospect of immersive experience of distant worlds using data returned by our probes. But what of the state of virtual reality today, a technology that is suddenly the talk of the computer world with the imminent release of the Oculus Rift device? Frank Taylor is just the man to ask. He has worked with computer graphics since the 1970s, starting at the University of Arizona. He worked several years at aerospace companies in support of DoD and NASA including simulation and virtual reality technology in support of astronaut training at NASA JSC. Frank has also been a successful entrepreneur doing work with Internet and other computer technologies. His most notable recent accomplishment was the completion of one orbit of the Earth at 0 MSL – he and his wife left in 2009 and sailed around the world arriving back in the US in 2015. Frank is the publisher of Google Earth Blog since 2005. Have a look now at the surprisingly wide possibilities already opening up for VR.

by Frank Taylor

For most of us reading Centauri Dreams, we have lived out our lives dreaming about travel to other stars and planets. Many of us have tried to satisfy our dreams vicariously by enabling the various unmanned missions to our non-terrestrial, solar system-based planets, Sun, moons, asteroids, and comets. Last summer, we were all captivated by watching the fly-by of our most distant planetary-like neighbor Pluto and its moon Charon.

In addition, we have over four centuries of both terrestrial and space-based telescopic observations to thank for our measured observations of both local and interstellar astronomical objects as far as our science has allowed. But, our hopes and plans of visiting other stars and planets for more direct observation has continued to elude us. For well known reasons documented here on Centauri Dreams.

Image: My friend Frank Taylor, photographed here on the Indian Ocean island of Reunion during his recent circumnavigation, which is fully documented (and with spectacular photography) on his Tahina Expedition site.

Computer Simulations of Space

As a career computer graphics scientist, I have been fortunate to simulate space-based operations for training astronauts, simulate remote tele-robotic space operations, and create animations depicting some of our in-orbit and planetary missions. I have also thoroughly documented the use of Google Earth for enumerable Earth depictions as well as involved in developing its use for other planets and moons in our solar system. I’ve published the Google Earth Blog since 2005 with almost daily news and stories about that program and its uses.

Going back to 1991, while working under contract with NASA JSC, I discovered a demonstration program on a Silicon Graphics workstation that was developed by an engineer named Erik Lindholm. It depicted a 3D simulation of the known local star systems, our entire solar system, and even had a few science fiction objects like Ring World around another star. The amazing thing was that you could travel between objects at speeds far exceeding known physics. Measurements were at multiples of C (speed of light). I was entranced by this experience of finally traveling to another star, and it wasn’t necessary to wait an unreasonable amount of real time to get there. For years afterwards, I wondered why someone had not ported the application to a wider audience (possibly less than 500 people saw that early one) – especially with the rapidly improving computer graphics capabilities of the typical desktop computer that decade.

In the 1990s, there were numerous planetarium applications that let you simulate the night sky, and some even let you visit other planets. But, it wasn’t until early 2001 that a real interstellar travel 3D simulator became popular. A program many of you may have heard of called Celestia (Wikipedia) was released and available for free. It mostly focused on the solar system, but also modeled a fair number of known star positions and compositions, and even allowed you to see an approximation of our galaxy and visit 3D versions of neighboring galaxies (but, not individual stars and planets).

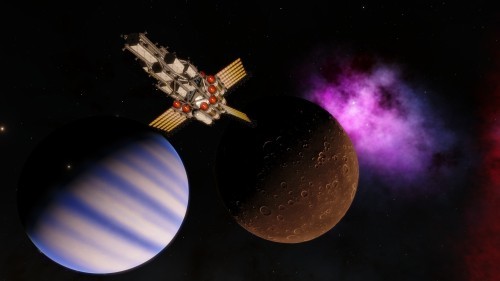

Image: Screenshot of Celestia loading data Version 1.6.1.

The developers ported Celestia to many operating systems (Windows, Mac, Linux, and even Amiga OS). An active community of fans contributed enhanced quality textures for planet surfaces, contributed ideas for educational tours, produced or converted 3D models of spacecraft (both real, design concepts, and fictional), and more.

For 10 years, Celestia was active. But, the developers stopped work by 2011. Celestia and community content is still available. Even if you have an older desktop or laptop, Celestia is likely to run well. Download Celestia here, and see the community content here. The caveat is that the graphics are based on older (circa 2000) generation products, and computer graphics cards have leaped ahead in quality in the last 15 years.

Current Generation Space Simulations

Recently, I was lamenting the lack of progress since Celestia, and discovered a link to an amazing Windows-based program called Space Engine (Wikipedia). This program is sure to make almost any astronomer, or Centauri Dreams fan, exclaim in awe and wonder for the opportunity to visualize and virtually experience interstellar destinations with almost artistic quality. Developed by a single programmer in Russia, whose name is Vladimir Romanyuk, with input from Russian astronomers and international scientists and fans, this program is amazing. In his own words Space Engine is described as:

“A free space simulation program that lets you explore the universe in three dimensions, from planet Earth to the most distant galaxies. Areas of the known universe are represented using actual astronomical data, while regions uncharted by astronomy are generated procedurally. Millions of galaxies, trillions of stars, countless planets – all available for exploration. You can land any planet, moon or asteroid and watch alien landscapes and celestial phenomena. You can even pilot starships and atmospheric shuttles.”

Image: Screenshot of Space Engine loading Version 0.9.7.4 showing moon terrain and atmosphere in orbit around oceanic planet.

Space Engine uses publicly available astronomical databases to represent the known stars and planets. Then he goes on to generate a suitable composition of remaining stars, star clusters, and nebulae for galaxies. Next, the program extrapolates planetary systems based on best guesses for physical compositions using orbital distances, star temperatures and types, and other factors. Planet classifications include gas giants, ringed worlds, desert planets, oceanic, ice, and more. Then he procedurally generates 3D terrain, and – when physically viable – water bodies, craters, mountains, canyons, volcanoes, and other terrain. The application then colorizes and adds textures to make the surfaces look realistic. Atmospheres are rendered, when present, including colorization based on physical composition and star colors. Space Engine even calculates whether life could be present on planets with the right characteristics. Also, a great deal of effort has been put into rendering black holes and accretion disks.

Here is a YouTube video by a fan reviewing an older version of Space Engine (by ObsidianAnt):

Video: A high resolution video showing samples of views in Space Engine with review commentary. Credit: YouTube, ObsidianAnt.

In attempt to make the program have a game-like feel, you can also add 3D space ships (including interstellar traveling ships) and actually fly them using a variety of supported controlling devices. Personally, I have plenty of fun just exploring stars and planetary systems without the spacecraft simulations. But, some readers here might have fun putting their favorite interstellar spacecraft designs into Space Engine.

Image: Screenshot from Space Engine showing spacecraft in front of moon and gas giant with nebula in background.

Space Engine is available for free for Windows only right now, but you have to own (or have access) to a relatively recent desktop with recent high-end video card, or a high-end gaming laptop, to run this powerful program well. Recommended requirements are listed on the bottom of the home page for Space Engine. If you want to try it, the latest version can be found (in the forums) here. Vladimir is asking for donations to help fund further development and ports to Mac and Linux. I encourage those who enjoy the program to make a donation.

Space Engine attempts to be a mirror of the real universe as we know it. With the main exception being that travel times are greatly reduced. Would you believe there is yet another category getting even more development attention involving virtual interstellar travel?

Computer Games with Space Simulations

It is widely known that computer graphics’ rapid technological advancement in the past 40+ years was not solely due to scientific application pursuits. An even bigger factor has been the advancement and popularity of computer games. The same thing is happening to space-based simulations. There is an acceleration of interest in space-based games that is advancing the technology of space simulations. While Space Engine has been developing admirably during the past two years with a sole programmer of talented skills, a number of space games have been developed with modern gaming development budgets in the millions of dollars, and requiring dozens of game software engineers, artists, writers, physics modeling, simulation software, database engineers, and a business marketing budget equal to half the overall budget or more.

Some of these games involve interstellar travel and exploration and science fiction themes involving mostly commerce, and the inevitable gaming need of military action to protect interests. The typical gamer takes on jobs of space mining to build a fortune to acquire bigger and better space ships. Then they graduate to military ships and space battles ensue on a massive scale. For example, one massively online role playing game called Eve Online (Wikipedia) hosted last October a large scale space ship battle involving the loss of 1,165 ships (which equated to in monetary conversion to US $13,000) with 1600 gamers participating ( story here by Michael Bonnet, PC Gamer).

Image: Image of Eve Online orbital battle scene by CCP Games.

My interest lies in games that generate realistic visualizations of interstellar systems using spacecraft that we might build ourselves for exploration (if we can overcome the physics to get over the distance factors). The best space game simulation example I have seen is a game called Elite Dangerous (Wikipedia) by Frontier Developments based in Cambridge, UK. Frontier have created not only very realistic renderings of space and spacecraft, but have also added highly versatile surface recon vehicles (SRVs) that you can drive on the surface of planetary bodies (available in their latest season called Horizons).

Image: Image of Elite Dangerous – program developed by Frontier Developments Plc.

Elite Dangerous star systems and planets are quite well rendered in many ways similar to Space Engine. The graphics and lighting are astonishingly real, as is the physics of the simulations. Of course, because it is a game, situations can involve space battles with competing factions for space-based mining and other commercial operations. But, you can also just explore on your own as demonstrated in this YouTube video which shows a tour of our Solar System:

Video: A high resolution video showing a tour of a future version of our solar system from the game Elite Dangerous: Horizons. Credit: YouTube, ObsidianAnt.

Some of our planets have changed a bit due to human influences over the next thousand years of space development. You will note that fine simulation details such as the rendering of instrumentation on the pilot stations with working indicators of thrust, gravity, attitude, fuel, scanning of terrain when landing, and other ship and object conditions. Ships can be controlled with a number controllers such as those used for flight simulation, game controllers, or even mouse and keyboard.

Image: Screenshot of rover on moon near planet in Elite Dangerous from YouTube video above by ObsidiantAnt.

As you can see, the budget of big games has resulted in an astonishing amount of simulation detail. You also may note that the video above was produced by the same person who created the video I shared for Space Engine. People who like the idea of interstellar travel gravitate their way to these similar space simulations.

The New Age of Virtual Reality

A major new influence of computer graphics is excitement surrounding the recent introduction of consumerized virtual reality technology. Virtual reality usually refers to immersive multimedia using computer simulation, accomplished through a head mounted display system representing stereoscopic 3D, or other multimedia, display, renderings and stereo audio. The idea of virtual reality technology and its development go back nearly as far back as the first computer graphics. The first immersive display system was built by Ivan Sutherland in 1968. It involved a heavy suspended helmet system with an early development of miniaturized cathode ray tube displays. The system became known as “Sword of Damocles”.

Image: Photograph of first VR system designed by Ivan Sutherland in 1968. The system became known as “Sword of Damocles”. A head mounted three dimensional display”, Ivan Sutherland, 1968.

In the late 1980s excitement about virtual reality reached beyond the purview of computer graphics researchers. This happened when advances in 3D graphics machines, display systems, 3D positioning devices, and hand-tracking devices began enabling interaction and a sense of immersion.

Of personal interest was that NASA was quite involved in research in VR in the 1980s. NASA Ames Research Center formed the Virtual Environment Workstation (VIEW) lab and was headed by Scott Fisher. In the early 80s, I worked at NASA JSC on the space shuttle simulator computer graphics used for training the astronauts. In the late 1980s I was working with engineers in a robotics simulation lab at NASA Johnson Space Center and one project was a VR helmet system used initially for research in training astronauts for the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) for space walks. Later (early 90s) this system was used for tele-robotic simulations I helped develop to explore controlling the robotic arms on the space station (which was still being designed at the time).

Science fiction books fed fuel to the VR fire, when William Gibson’s book Neuromancer (1984) introduced the term “cyberspace” in the early 80s. Later, Neal Stephenson published Snow Crash (1992) which popularized a concept of a virtual reality rendered universe, which he called the “Metaverse”, which humans could visit and be represented through an avatar in a 3D world with shared defined places.

Hype about VR became widespread in the technology industry first in the late 80s. Then gaming companies in the early 90s announced VR systems that could be used in the popular video arcades. A movie called The Lawnmower Man (1992, Wikipedia) helped introduce the concept of VR to an even wider audience. Probably the most popularized science fiction concept of virtual reality was introduced in the late 80s in the form of Star Trek: The Next Generation (TV series, 1987, Wikipedia) with the “holodeck”. Of course, the holodeck is still the ultimate dream of a lot of VR enthusiasts.

Unfortunately, the capabilities used by researchers involved in VR in the 80s and 90s used very expensive computer graphics workstations and display devices. And, the displays were very crude at about 320×240 resolution at best. It was not yet possible to create cost effective, or realistic-looking systems at that time. The resulting game VR systems were crude and underwhelming when they came to market. Companies investing in the technology lost a lot of money and the concept’s popularity waned. I actually left NASA in 1992 intending to form a VR company, but my business planning fortunately revealed the impending dilemma and I instead started an Internet company. The impact of the burst of VR hype in that period of time, reduced interest in investment of consumer VR for the next 20 years. Far longer than I, or many other people, would have believed.

In 2012, an enterprising 19-year-old VR fan by the name of Palmer Luckey introduced the concept of building a new head mounted display (HMD) system using the now much more advanced computer graphics capabilities of desktop computers. Advances in display systems for mobile phones made possible much higher resolution displays for VR in a more lightweight HMD.

Palmer Luckey’s idea was an example of impeccable timing. He formed a company called Oculus to build his first system to be called the Oculus Rift. Within months, his company introduced the idea of raising funding through the crowdfunding site Kickstarter. He already had a large following in the gaming community because of an association with the most revered computer graphics gaming guru John Carmack. His goal was to raise $250,000. The concept was so popular that the goal was reached within four hours, and ended up raising nearly 2.5 million dollars instead. Although most of the contributors were gamers, the applications of VR reach a far wider range. Possibly the largest is entertainment as 360 filming has become practical and is very impressive.

By the end of 2013, Oculus had raised $75 million dollars in investment, headed by the leading technology investment broker Andreesen Horowitz. In March of 2014, Mark Zuckerberg announced on Facebook that they would be acquiring Oculus for $2 billion. Needless to say, this greatly raised attention to VR.

Even with the resulting flood of money, it would take two years to prepare the first Oculus Rift for consumer sales. However, Oculus also worked with Samsung to introduce an HMD called GearVR that works with top-end Samsung smartphones as the display device for only $100. It became widely available to consumers in 2015. The first Oculus Rift became available for pre-order in early January 2016. The first units are scheduled for delivery March 28, 2016. The difference between the GearVR and the Rift are greater fidelity and performance of computer graphics, better visual optics and positional tracking, 3D controllers and more versatility with a multi-tasking operating system. A competitor to Oculus from HTC called Vive started pre-orders on February 29, 2016. It has the ability to stand up and move around, and has two 3D hand-controllers for interaction.

Despite the delayed delivery to consumers, Oculus has reportedly shipped 200,000 units of prototype Oculus Rift units worldwide to software developers since early 2014. Numerous software products, in particular games, have introduced support for the Oculus Rift (and other Head Mounted Displays which have since been announced by other companies). And, over $2 billion in addition investments have gone towards the ecosystem of new VR companies in the last two years alone. Top analysts are predicting huge forecasts for adoption, but it’s a little early to say what the reaction will be until the new consumer products are on the shelves and real software ships.

Image: Oculus Rift pre-order entry page January 6, 2016 with photo showing the components in the Oculus Rift package. First deliveries were scheduled for March 28, 2016.

VR in Space Simulations Today

Both Space Engine and Elite Dangerous have support for VR. In Space Engine, you can both gaze in wonder at the beauty of the universe, but also sense the scale and grandeur of nearby planets, moons, nebulae, and stars. While the system works well for Space Engine, the sense of immersion and 3D effects are much more pronounced in Elite Dangerous due to the primary placement being in the pilot seat of the space craft used for exploration. Stereoscopic 3D immersion is much more noticeable for objects in close proximity due to parallax. Hence the views are even more immersive in Elite Dangerous and the simulations of landing on a planet are quite exciting. Needless to say, these space-based experiences are very gratifying to me as a long-time believer in VR, especially with actual VR experience dating back to 1990.

Meanwhile, NASA and aerospace companies have continued to use VR for space simulations throughout the past 20 years. Some of the very same engineers I worked with in the early 90s started a VR Lab at JSC and have been using VR to train astronauts ever since (see article by Erin Carson at Tech Republic).

One of the most talked-about space VR programs is an educational story about the Apollo 11 mission to the moon. You can watch elements from launch to the historic moment when Armstrong steps on the moon. The in-development product has already won awards because of the strong emotional impact it has had on its viewers, and videos and demos are available for viewing in VR. You can watch a 360 video trailer of the Apollo 11 VR produced by Immersive VR Education out of Dublin, Ireland here (if you have cardboard you can watch it in 3D):

The new consumer space simulations software like Space Engine and Elite Dangerous are the closest most of us or going to get today to experiencing the exploring distant interstellar worlds and places. However, it should be noted that the requirements for the new consumer VR HMDs does have even higher system requirements for faster processors, memory, and video cards.

Interstellar researchers and exploration dreamers take note. Your chance for travel to the stars is virtually here.

March 17, 2016

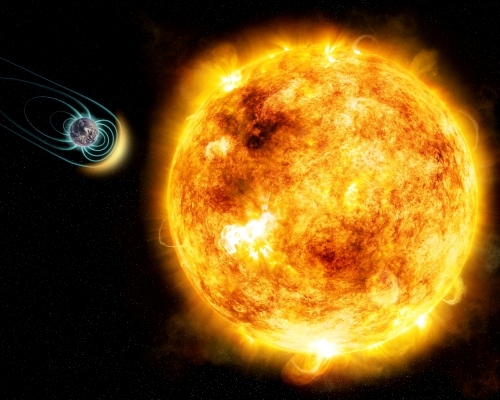

Protecting Life on the Early Earth

Kappa Ceti is a young star — 400 to 600 million years old — in the constellation Cetus (the Whale). It’s a tremendously active place, its surface disfigured by starspots much larger and more numerous than we find on our more mature Sun. In fact, Kappa Ceti hurls enormous flares into nearby space, ‘superflares’ releasing 10 to 100 million times the energy of the largest flares we’ve ever observed on the Sun. What would be the fate of planets around a star like this?

The question is directly relevant to our own system because Kappa Ceti is a G-class dwarf much like the Sun, giving us a look at what conditions would have been like when our own system was forming. The calculated age of the star, extrapolated from its spin, corresponds to the time when life first appeared on the Earth. Thus we’re seeing a model of our distant past, one that makes it clear that a magnetic field is an essential for planetary habitability.

The violent activity on the surface of Kappa Ceti is driving a steady stream of plasma into space, a ‘stellar wind’ that is fifty times stronger than what we observe from the Sun. A planet without a strong magnetic field would potentially lose most of its atmosphere in this maelstrom. Lead author Jose-Dias do Nascimento (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) and team note in the paper on this work that the 400 to 600 million year time frame in stellar age also corresponds to the time when Mars lost its liquid water some 3.7 billion years ago.

Understanding the interactions between the stellar wind and the surrounding planetary system, then, helps us get a read on the early history of our own system. From the paper:

A key factor for understanding the origin and evolution of life on Earth is the evolution of the Sun itself, especially the early evolution of its radiation field, particle and magnetic properties. The radiation field defines the habitable zone, a region in which orbiting planets could sustain liquid water at their surface (Huang 1960; Kopparapu et al. 2013). The particle and magnetic environment define the type of interactions between the star and the planet. In the case of magnetized planets, such as the Earth that developed a magnetic field at least four billion years ago (Tarduno et al. 2015), their magnetic fields act as obstacles to the stellar wind, deflecting it and protecting the upper planetary atmospheres and ionospheres against the direct impact of stellar wind plasmas and high-energy particles (Kulikov et al. 2007; Lammer et al. 2007).

Image: In this artist’s illustration, the young Sun-like star Kappa Ceti is blotched with large starspots, a sign of its high level of magnetic activity. New research shows that its stellar wind is 50 times stronger than our Sun’s. As a result, any Earth-like planet would need a magnetic field in order to protect its atmosphere and be habitable. The physical sizes of the star and planet and distance between them are not to scale. M. Weiss/CfA.

The researchers used spectropolarimetric observations — measuring the optical properties of polarized light at different wavelengths — to analyze Kappa Ceti’s magnetic fields, combining these with models of stellar winds. Data were collected using a spectropolarimeter at the 2-meter Bernard Lyot Telescope (TBL) of Pic du Midi Observatory in the French Pyrenees.

Working with the magnetic properties of the young Earth and factoring in the strength of the young Sun’s plasma outflows allowed the team to estimate the size of the early Earth’s magnetosphere, which is found to be one-third to one-half as large as it is today. “The early Earth,” says do Nascimento, “didn’t have as much protection as it does now, but it had enough.”

The paper is do Nascimento et al., “Magnetic field and wind of Kappa Ceti: towards the planetary habitability of the young Sun when life arose on Earth,” accepted for publication at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint). A CfA news release is also available.

March 16, 2016

What Ceres’ Bright Spots Can Tell Us

Garrett P. Serviss was a writer whose name has been obscured by time, but in his day, which would be the late 19th and early 20th Century, he was esteemed as a popularizer of astronomy. He began with the New York Sun but went on to write fifteen books, eight of which focused on the field. He was also a science fiction author whose Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898), which took Wellsian ideas right out of War of the Worlds and was a sequel to an earlier story, involved master inventor Thomas Edison in combat against the Martians both on the Martian surface and off it.

I think this is the first appearance of spacesuits in fiction. In any case, Serviss anticipates the ‘space opera’ to come, and will always have a place in the history of science fiction. I can only wonder what he would have made of the Dawn mission at Ceres. In Edison’s Conquest of Mars, he refers to a race of ‘Cerenites’ who are, because of the low gravity of their world, about forty feet tall. They are at war with the Martians, and thus allies of Earth.

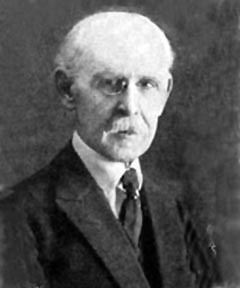

Image: Author and science popularizer Garrett P. Serviss.

Forgive the digression, but I’m always interested in the work of people who bring science to the public, and it’s clear that Serviss’ interest in Ceres would have been profound, as works like Other Worlds: Their Nature, Possibilities and Habitability in the Light of the Latest Discoveries (1901) demonstrate. From Other Worlds, this look at Ceres and the asteroid belt as understood at the turn of the 20th Century:

The entire surface of the largest asteroid, Ceres, does not equal the republic of Mexico in area. But Ceres itself is gigantic in comparison with the vast majority of the asteroids, many of which, it is believed, do not exceed twenty miles in diameter, while there may be hundreds or thousands of others still smaller—ten miles, five miles, or perhaps only a few rods, in diameter!

Hundreds or thousands indeed. Another Serviss book, Astronomy with an Opera-glass (1888), holds up pretty well even today. Another thing I like about him is that in his science fiction, he writes scientists into the plot. Not just Edison, but Edward Emerson Barnard and Wilhelm Röntgen, to name but a few.

A New Look at Occator

But enough of early science fiction and on to Ceres today. Even before Dawn, we had made recent strides, nailing Ceres’ rotation rate, for example, by 2007, at 9.074170 hours. Those odd bright spots on the surface were evidently picked up in 2003 Hubble measurements, which showed a spot that moved with Ceres’ rotation, and water vapor plumes erupting from the surface have been reported using Herschel data, suggesting possible volcano ice geysers.

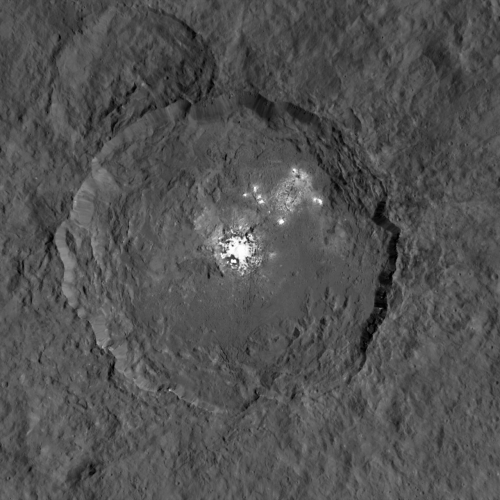

Now, of course, we’ve homed in on the bright spots in Ceres’ Occator crater, and the speculation about their origin continues. Are we looking at a relatively recent impact crater that has revealed bright water ice? Cryo-volcanism or icy geysers have also been suggested. As of today, we still don’t know whether the bright spots are made of ice, or evaporated salts, or some other material. A new study using the HARPS spectrograph at La Silla (Chile) has just appeared, showing us that whatever they are, the bright spots show changes over time.

Lead author Paolo Molaro (INAF–Trieste Astronomical Observatory) explains the method:

“As soon as the Dawn spacecraft revealed the mysterious bright spots on the surface of Ceres, I immediately thought of the possible measurable effects from Earth. As Ceres rotates the spots approach the Earth and then recede again, which affects the spectrum of the reflected sunlight arriving at Earth.”

Image: The bright spots on Ceres imaged by the Dawn spacecraft.

The changes Molaro’s team has found are subtle — remember that nine-hour rotation rate, which means the motion of the spots toward and away from Earth is on the order of 20 kilometers per hour. But the Doppler shift caused by the motion can be revealed by an instrument as sensitive as HARPS. Over two nights of observation in July and August of 2015, the researchers found the spectrum changes they expected to see from this rotation, but they also recorded random variations from night to night that came as a surprise.

The paper lays out a possible cause: The bright spots could be providing atmosphere in this region of Ceres, which would confirm the earlier Herschel water vapor detection. Pointing toward this conclusion is the fact that the bright spots appear to fade by dusk, an indication that sunlight may play a significant role, possibly heating up ice just beneath the surface and causing the emergence of plumes:

It is possible to speculate that a volatile substance could evaporate from the inside and freezes when it reaches the surface in shade. When it arrives on the illuminated hemisphere, the patches may change quickly under the action of the solar radiation losing most of its reflectivity power when it is in the receding hemisphere. This could explain why we do not see an increase in positive radial velocities, but all the changes in the radial velocity curves are characterized by negative values. After being melted by the solar heat, the patches can form again during the four-hours-and-a-half duration of the night, but not exactly in the previous fashion, thus the RV curve varies from one rotation to the other. It is possible that the cycle of evaporation and freezing could last more than one rotational period and so the changes in the albedo which are responsible of the variations in the radial velocity.

As this ESO news release points out, the volatile substances evaporating under solar radiation could be freshly exposed water ice, or perhaps hydrated magnesium sulfates. The spots are brightest in the morning when their plume activity reflects sunlight effectively, but as they evaporate, the loss of reflectivity produces the changes analyzed in the HARPS data. We can add to the mix a recent paper in Nature (see below) that reports localized bright areas consistent with hydrated magnesium sulfates and probable sublimation of water ice.

So the mysterious bright spots of Ceres continue to tantalize us. As the paper notes, the fact that we find several bright spots in the same basin (Occator crater) seems to point to a volcano-like origin, but that would imply that an isolated dwarf planet can be thermodynamically active. Such activity is no surprise in large satellites around the gas giants, where tidal effects are assumed to play a major role, but its sources on Ceres will need further investigation.

The paper is Molaro et al., “Daily variability of Ceres’ Albedo detected by means of radial velocities changes of the reflected sunlight,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Vol. 458, No. 1 (2016), L-54-L58 (abstract). The Nature paper is Natues et al., “Sublimation in bright spots on (1) Ceres,” Nature Vol. 528 (10 December 2015), 237-240 (abstract).

March 14, 2016

StarSearch: Our Hunt for a New Home World

His interest fired by an interview with interstellar researcher Greg Matloff, Dale Tarnowieski became fascinated with the human future in deep space. One result is the piece that follows, an essay that feeds directly into a recent wish of mine. I had been struck by how many people coming to Centauri Dreams are doing so for the first time, and thinking that I would like to run the occasional overview article placing the things we discuss here in a broader context. Dale’s essay does precisely this, looking at our future as a species on time frames that extend to the death of our planet. Dale retired in January 2015 from the position of assistant director of communications with New York City College of Technology/CUNY, a veteran journalist and editor of “Connections,” the college’s print and online magazine. He also did considerable writing for the New York City College of Technology Foundation and its annual Best of New York Award Dinner (and continues to do so on a freelance basis). Here he reminds us of the Sun’s fate and asks how — if we and our planet get through our technological infancy — we will find ways to move into the Solar System and, eventually, out into the Orion Arm.

By Dale Tarnowieski

Mother Earth – our home, sweet home – won’t be our home forever. In one billion years, give or take, increased heat from a steadily warming Sun will cause our planet’s temperatures to double, its oceans to boil away, and its land surfaces to turn to sand or melt. Assuming we’re still around, we’ll have to relocate before that happens.

A billion years is a long time off, so why the hurry to establish a foothold in space? One answer comes from astrophysicist Stephen Hawking, who warns that we may have as few as 200 years to establish permanent settlements on other worlds and begin mining our solar system for its bounty. Our numbers and the depletion of our planet’s finite resources are growing exponentially, as is our ability to alter the biosphere for good and ill. Within two centuries, Hawking contends, we could exhaust the resources available on Earth essential to our survival and damage our environment beyond repair.

But assuming we successfully respond to these more immediate challenges, the longer-term threat to our survival posed by a progressively warming Sun is one we won’t be able to avoid. We are already contemplating the use of mirrors in space to deflect sunlight as an anti-global warming measure as well as devices called space sunshades at neutral-gravity positions in the Earth-Sun system to reduce the increasing heat from our parent star. But such devices will do nothing to protect us when that heat becomes so intense that our only option will be to abandon our planet.

Now middle-aged, the Sun’s luminosity has increased 30 percent since its birth 4.6 billion years ago and will increase another 10 percent over the next one billion years. The radius of a more luminous Sun is projected to expand an estimated 200 times within four-to-five billion years and Mercury, Venus and possibly Earth and Mars will be vaporized.

Numerous natural or man-made catastrophes could bring most or all life on Earth to an end before the excessive heat from a warming Sun compels humankind’s relocation. But assuming no such catastrophe occurs, that move is only the first of two we’ll have to make. Several billion years later, it will be necessary to leave the solar system altogether as our dying Sun begins to swell.

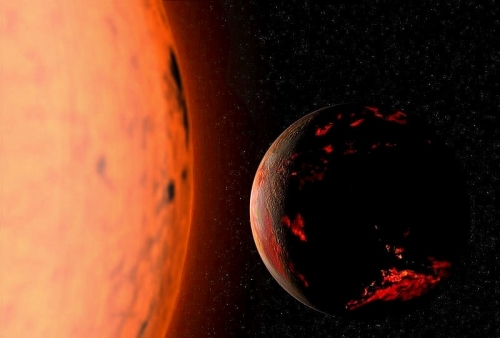

Image: A charred and glowing Earth of the far future, the Sun having long since entered its red giant phase. Credit: Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

Holding Off the Inevitable

Could the abandonment of our world be avoided? In 2001, researchers Don Korycansky of the University of California-Santa Cruz, Gregory Laughlin of NASA and Fred Adams of the University of Michigan suggested that by maneuvering an asteroid 100 kilometers wide approximately 16,000 kilometers above Earth’s surface once every 6,000 years, we could slowly nudge our planet away from a more luminous Sun. But a collision with an object of such size would only have to happen once to prove catastrophic.

When our time on Earth runs out, the fortunate among us will join those already dwelling aboard orbital settlements circling more distant planets or their moons. Current thinking envisions others relocating to huge mobile in-space habitats called world ships or to open-air or enclosed settlements on Mars – the open-air variety depending on our successfully terraforming, or environmentally modifying, the biosphere of what at present is a frozen desert of a planet.

None of the other planets in our solar system is now remotely habitable. Closer to the Sun, a nearly atmosphere-free Mercury’s temperatures vary between -173 Celsius at night to +427 Celsius during the day. The latter is hot enough to melt lead. Venus is even hotter and possesses one of the deadliest atmospheres in the solar system. Farther from the Sun than Earth, Mars’s thin atmosphere is composed mostly of carbon dioxide and the planet’s weak gravity poses problems with respect to the retention of atmospheric gases. The four even more distant giants – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – all have relatively small, dense cores surrounded by massive layers of gas. Jupiter and Saturn have thick atmospheres consisting primarily of hydrogen and helium, while Uranus is a world of liquid ice and Neptune home to wind speeds ten times those of the strongest hurricanes on Earth.