Paul Gilster's Blog, page 143

October 20, 2016

New Work on Planet Nine

Considering how long we’ve been thinking about a massive planet in the outer Solar System — and I’m going all the way back to Percival Lowell’s Planet X here — the idea that we might find the hypothetical Planet Nine in just three years or so is a bit startling. But Caltech’s Mike Brown and colleague Konstantin Batygin, who predicted the existence of the planet last January based on its effects on Kuiper Belt objects, are continuing to search the putative planet’s likely orbital path, hoping for a hit within the next few years, a welcome discovery if it happens.

The duo are working with graduate student Elizabeth Bailey, lead author of a new study being discussed at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, which is occurring in conjunction with the European Planetary Science Congress. The new paper is all about angles and alignments, focusing on the fact that the relatively flat orbital plane of the planets is tilted about six degrees with respect to the Sun. That’s an oddity, and Planet Nine, hypothesized to be about ten times the mass of the Earth and in an orbit averaging 20 times Neptune’s distance from the Sun, just may be the cause.

The calculations on display in the new paper depict a planet some 30 degrees out of alignment with the orbital plane of the other planets. That can help to explain orbital observations of Kuiper Belt objects, but also the unusual system-wide tilt, which stands out because of the assumed formation of the planets through the collapse of a spinning cloud into a disk and, eventually, a collection of planets orbiting the Sun. We would expect the angular momentum of the planets to maintain a rough alignment with the Sun along the orbital plane.

Unless, of course, something is disrupting the system. Throw in the angular momentum of Planet Nine, based on its assumed mass and distance from the Sun, and profound effects on the system’s spin become evident, creating a long-term wobble that shows up in the system’s tilt. As Bailey puts it, “Because Planet Nine is so massive and has an orbit tilted compared to the other planets, the Solar System has no choice but to slowly twist out of alignment.”

And this from the paper:

… a solar obliquity of order several degrees is an expected observable effect of Planet Nine. Moreover, for a range of masses and orbits of Planet Nine that are broadly consistent with those predicted by Batygin & Brown (2016); Brown & Batygin (2016), Planet Nine is capable of reproducing the observed solar obliquity of 6 degrees, from a nearly coplanar configuration. The existence of Planet Nine therefore provides a tangible explanation for the spin orbit misalignment of the solar system.

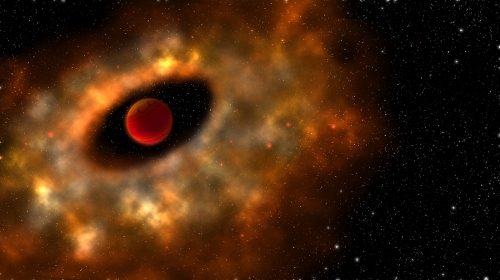

Image: This artistic rendering shows the distant view from Planet Nine back towards the sun. The planet is thought to be gaseous, similar to Uranus and Neptune. Hypothetical lightning lights up the night side. Credit: Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC).

The six-degree tilt we see between planetary disk and Sun thus fits into the team’s calculations regarding Planet Nine’s size and distance from the central star. And if this does indeed turn out to be the explanation, speculation will then center on how Planet Nine came to be so far out of line with the other planets. We know that gravitational interactions in young planetary systems can sometimes result in disruption, causing some planets to be thrown out of their systems, and others to be moved into distant orbits. Such gravitational byplay may well be the reason for Planet Nine’s unusual position. Now we just need to discover the planet.

I also want to mention that Renu Malhotra (University of Arizona) and team have continued their analysis of a possible Planet Nine, likewise presenting their results at the AAS/EPSC meeting in Pasadena. Through analysis of what they call ‘extreme Kuiper Belt Objects’ —on eccentric orbits with aphelia hundreds of AU out — the team finds a clustering of orbital parameters that may point to the existence of a planet of 10 Earth masses with an aphelion of more than 660 AU. Two orbital planes seem possible, one at 18 degrees offset from the mean plane, the other inclined at 48 degrees.

Dr. Malhotra confirmed in an email this morning that her own constraints on the current position of this possible planet line up with Mike Brown and team at Caltech. But her team continues to point out that we have no detection at this point, and much to learn about the orbits of the Kuiper Belt objects under study. From her paper:

…we note that the long orbital timescales in this region of the outer solar system may allow formally unstable orbits to persist for very long times, possibly even to the age of the solar system, depending on the planet mass; if so, this would weaken the argument for a resonant planet orbit. In future work it would be useful to investigate scattering efficiency as a function of the planet mass, as well as dynamical lifetimes of non-resonant planet-crossing orbits in this region of the outer system. Nevertheless, the possibility that resonant orbital relations could be a useful aid to prediction and discovery of additional high mass planets in the distant solar system makes a stimulating case for renewed study of aspects of solar system dynamics, such as resonant dynamics in the high eccentricity regime, which have hitherto garnered insufficient attention.

The Bailey, Batygin & Brown paper is “Solar Obliquity Induced by Planet Nine,” accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal (preprint). The Malhotra paper is Malhotra, Volk & Wang, “Coralling a Distant Planet with Extreme Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 824, No. 2 (20 June 2016). Abstract / preprint.

October 19, 2016

New Horizons: Looking Further Out

We’re getting close on New Horizons data, all of which should be downlinked as of this weekend. Although that’s a welcome marker, it hardly means the end of news from the doughty spacecraft. For one thing, we have years of analysis ahead of us as we bring the abundant data from the spacecraft’s instrument packages into focus. For another, we’re still in business out there in the Kuiper Belt, heading for that interesting object 2014 MU69.

Who knows what will turn up at the latter, given our propensity to be surprised at every turn in interplanetary exploration, from Triton’s volcanic plains to fabulously fractured Miranda. And, of course, Pluto and Charon themselves, which turned out to be so interesting that Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons, is already talking about future missions there.

But back to 2014 MU69, which has continued to be the subject of Hubble observations even as New Horizons homes in on the object. As this news release from the mission points out, MU69 is the smallest KBO ever to have its color measured, a reddish hue that confirms its identity as part of the ‘cold classical’ region of the Kuiper Belt. These are objects with low orbital eccentricity and inclination that are not in orbital resonance with Neptune. Reddish-brown tholins formed by solar radiation interacting with simple organic compounds are common here.

“The reddish color tells us the type of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69 is,” says Amanda Zangari, a New Horizons post-doctoral researcher from Southwest Research Institute. “The data confirms that on New Year’s Day 2019, New Horizons will be looking at one of the ancient building blocks of the planets.”

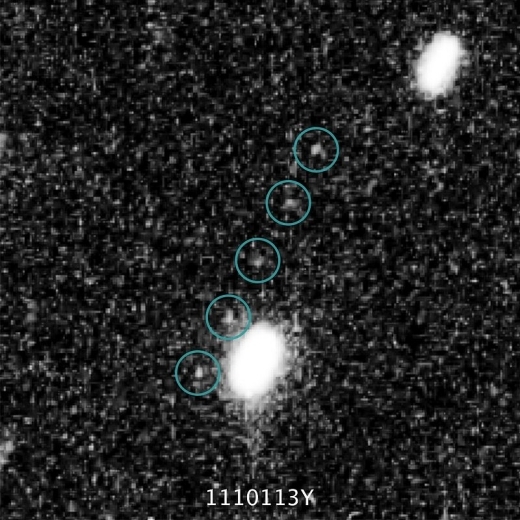

Image: 2014 MU69 travels diagonally across a dense field of stars and noise in the background. Credit: NASA, ESA, SwRI, JHU/APL, and the New Horizons KBO Search Team.

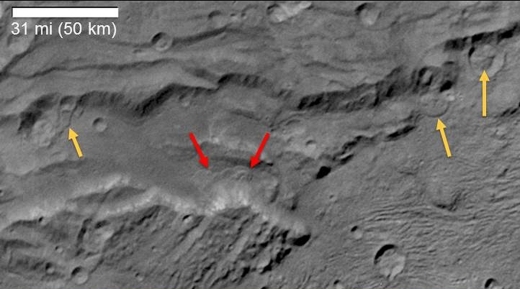

New Horizons has now covered a third of its distance from Pluto to MU69, with the target approximately a billion kilometers away. The analysis of New Horizons data, meanwhile, is turning up interesting things on Charon, where we find landslides, a feature that has not yet been spotted on Pluto’s surface, although we’ve found them on worlds as diverse as Mars and Iapetus. The Charon landslides are the farthest ever observed from the Sun.

Image: Scientists from NASA’s New Horizons mission have spotted signs of long run-out landslides on Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. This image of Charon’s informally named Serenity Chasma was taken by New Horizons’ Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on July 14, 2015, from a distance of 78,717 kilometers. Arrows mark indications of landslide activity. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Likewise, we learn that while Pluto’s atmosphere is hazy but largely cloud-free, a handful of possible clouds have turned up in New Horizons imagery. That would point to an atmosphere still more complex than expected. And the variations in surface brightness on Pluto itself are telling. Some of these regions, particularly in Pluto’s now famous heart-shaped region, are among the most reflective in the Solar System. This has implications for what may be occurring on another deep space object, says Bonnie Buratti (JPL), a co-investigator on the New Horizons science team:

“That brightness indicates surface activity. Because we see a pattern of high surface reflectivity equating to activity, we can infer that the dwarf planet Eris, which is known to be highly reflective, is also likely to be active.”

Image: Pluto’s present, hazy atmosphere is almost entirely free of clouds, though scientists from NASA’s New Horizons mission have identified some cloud candidates after examining images taken by the New Horizons Long Range Reconnaissance Imager and Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera, during the spacecraft’s July 2015 flight through the Pluto system. All are low-lying, isolated small features-no broad cloud decks or fields – and while none of the features can be confirmed with stereo imaging, scientists say they are suggestive of possible, rare condensation clouds. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

We’re a long way from through with New Horizons, which should make its flyby of 2014 MU69 on January 1, 2019 after the series of four course changes that adjusted its trajectory. We may have other outer system news to discuss as the joint meeting of the American Astronomical Society Division for Planetary Sciences and European Planetary Science Congress in Pasadena continues this week. But for now, I particularly like Alan Stern’s words:

“We’re excited about the exploration ahead for New Horizons, and also about what we are still discovering from Pluto flyby data. Now, with our spacecraft transmitting the last of its data from last summer’s flight through the Pluto system, we know that the next great exploration of Pluto will require another mission to be sent there.”

October 18, 2016

Antimatter Sail: Focus on Storage

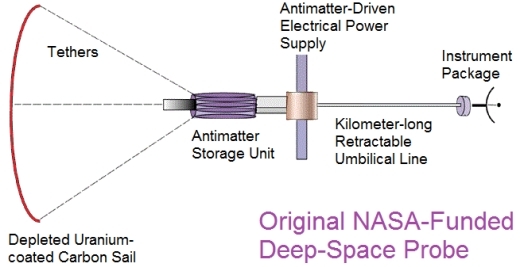

An antimatter sail, as described yesterday in the work of Gerald Jackson and Steve Howe, is an exciting idea particularly because it relies on only small amounts of antimatter, tapping its energies to create fission in a uranium-enriched sail. Thus the uranium is the fuel and the antimatter, as Jackson says, is the ‘spark plug.’ We reduce the needed amount of antimatter and define what the new Kickstarter campaign calls “…the first proposed antimatter-based propulsion system that is within the near-term ability of the human race to produce.”

The antimatter sail produces fission by allowing antimatter, stored probably as antihydrogen, to drift across to the sail, and as we saw yesterday, the potential for velocities up to 5 percent of lightspeed mean that such a sail could be deployed on interstellar missions. Proxima Centauri naturally emerges as a target, but Jackson and Howe’s work is not a result of recent interest in that star and its one known planet. The 2002 study in which they describe the antimatter sail was originally created for a probe to 250 AU (a Kuiper Belt and heliopause mission), drawing on work on a 10 kg instrument payload that was done at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

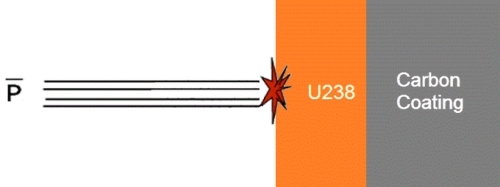

Image: Antiproton striking the depleted uranium coating on a carbon sail. Credit: Gerald Jackson/Hbar Technologies.

The just launched Kickstarter campaign is to re-think that earlier work in the context of an unmanned mission to a nearby solar system. Among the specific campaign goals is to create a detailed design for long-lived antimatter storage, a key issue in any such concept. After all, we have to store the antimatter in such a way that it does not annihilate with the normal matter surrounding it. We’ve known that this can be done for some time. In fact, it was back in 1984 that physicist Hans Dehmelt demonstrated how to hold a single positron in a cylinder using electric and magnetic fields. Dehmelt gave his device the name ‘Penning trap,’ a nod to Frans Penning, a Dutch physicist who saw that a magnetic field could steer electrons into tight orbits.

Dehmelt would go on to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1989 for co-developing the Penning trap technique with Wolfgang Pauli (each shared one-half of the prize). By adjusting the voltage and strength of the magnetic field, the Penning trap would become a viable way to store tiny amounts of antimatter.

But as antimatter storage has become feasible, problems grow as we begin storing more and more of the stuff. Try to contain large amounts of positrons or antiprotons and their like charges repel. Thus large quantities of antimatter — and compared to current levels of production, we need large quantities indeed — experience repulsive forces between them that quickly become stronger than the magnetic container can handle. Soon the magnetic ‘bottle’ begins to leak and the antiparticles are destroyed.

In his book Antimatter (Oxford University Press, 2010), Frank Close notes that even a millionth of the amount of antimatter needed for a Mars trip would create tons of electric force on the walls of the tank. That’s a daunting thought, and this is for a nearby target, although Close isn’t thinking in terms of the antimatter sail concept, which minimizes the amount of antimatter needed. Even so, high-capacity storage of antimatter has to be addressed.

What Jackson and Howe have been looking at for their antimatter sail involves storing the antimatter in the form of antihydrogen (a positron orbiting an antiproton). Here we’re at the heart of the original work the duo did for NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts, from which the antimatter sail took root. A key goal of the new Kickstarter campaign is to produce a design report describing how to build an antihydrogen storage bottle that can be used aboard a spacecraft. Their extensive experience with the issues makes Jackson and Howe an ideal team to push spacecraft antimatter storage forward.

I’m looking back at the original NIAC report Steve Howe prepared for NASA, which envisions storing antihydrogen in the form of frozen pellets rather than in traps, the idea being to use integrated circuit chips of the kind we have become familiar with through today’s microprocessors. We would deploy the same kind of etching technology to create a series of tunnels on each chip, with wells at periodic intervals where the antihydrogen pellets would be held. Changing the voltage allows pellets to move down these tunnels from well to well.

Remember the concept here: The antimatter, as it emerges from the storage device (held some 12 meters behind the sail) is then accelerated so that it drifts out into contact with the sail. But Jackson and Howe’s thinking is clearly evolving on this matter. The plan discussed on the Kickstarter site is to create an antihydrogen storage bottle based on methods Robert Millikan and Harvey Fletcher used in the early 20th Century to measure the charge of the electron. As this involved observing charged oil droplets between two metal electrodes, its uses may supercede the kind of chip technology originally envisioned. And further research, Jackson says, may actually involve antilithium rather than antihydrogen as the optimum form of antimatter.

A key requirement, of course, is portability — this is a storage method that has to be applicable to spacecraft. At Hbar Technologies’ headquarters, Jackson and Howe have the first portable storage bottle for such uses, one able to store positrons or antiprotons at liquid helium temperatures in a hard vacuum. Jackson’s experience with storage also extends to the design and construction of particle accelerator storage rings. Forcing storage technology forward is the need to house amounts of antimatter too large to store as charged elementary particles.

Image: Original portable antimatter storage bottle built by Penn State University and JPL.

I’ve focused on storage, but it’s clear that a lot of things have to go right to get to an interstellar antimatter sail. Key parameters for the Kickstarter effort are to drill down further on antimatter storage issues while at the same time describing renewed antiproton production possibilities at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The effort will recast the original study by way of firming up or adjusting earlier parameters in sail physics and engineering. The thrust-test apparatus developed through the NIAC grant will be upgraded and test facilities identified; here I would imagine experiments involving uranium-laden foils and antiproton interactions. Jackson and Howe also want to design an antihydrogen experiment to be funded in a later campaign.

To me, the possibility of a renewed and improved antiproton process at Fermilab is quite interesting, as we’ve seen what minute amounts our technologies are currently able to generate. In addition to an investigation like this, I would imagine Jackson and Howe will want to look at James Bickford’s ideas on natural antimatter production within the Solar System (see, for example, Antimatter Acquisition: Harvesting in Space, or search the archives here for more).

Bickford argues that space harvesting of antimatter is five orders of magnitude more cost effective than producing antimatter on Earth, an idea Jackson and Howe may want to contest if the highly restricted antimatter yields at Fermilab can be adjusted and improved. For more, see the Kickstarter page for this effort and keep an eye on Jackson and Howe’s Antimatter Drive site. The page there is not yet populated, but the intent is to archive all previous work on the antimatter sail, including a great deal of continuing studies on these storage concepts.

October 17, 2016

Antimatter and the Sail

An antimatter probe to a nearby star? The idea holds enormous appeal, given the colossal energies obtained when normal matter annihilates in contact with its antimatter equivalent. But as we’ve seen through the years on Centauri Dreams, such energies are all but impossible to engineer. Antimatter production is infinitesimal, the by-product of accelerators designed with a much different agenda. Moreover, antimatter storage is hellishly difficult, so that maintaining large quantities in a stable condition requires multiple breakthroughs.

All of which is why I became interested in the work Gerald Jackson and Steve Howe were doing at Hbar Technologies. Howe, in fact, became a key source when I put together the original book from which this site grew. This was back in 2002-2003, and I was captivated with the idea of what could be called an ‘antimatter sail.’ The idea, now part of a new Kickstarter campaign being launched by Jackson and Howe, is to work with mere milligrams of antimatter, allowing antiprotons to be released from the spacecraft into a uranium-enriched, five-meter sail.

Reacting with the uranium, the antimatter produces fission fragments that create what could be considered a nuclear-stimulated ablation blowing off the carbon-fiber sail. As to the reaction itself, Jackson and Howe would use a sheet of depleted uranium U-238 with a carbon coating on its back side. Here’s how the result is described in the Kickstarter material now online:

When antiprotons… drift onto the front surface, their negative electrical charge allows them to act like an orbiting electron, but with different quantum numbers that allow the antiprotons to cascade down into the ground orbital state. At this point it annihilates with a proton or neutron in the nucleus. This annihilation event causes the depleted uranium nucleus to fission with a probability approaching 100%, most of the time yielding two back-to-back fission daughters.

Now we get into a serious kick for the spacecraft:

A fission daughter travelling away from the sail at a kinetic energy of 1 MeV/amu has a speed of approximately 13,800 km/sec, or 4.6% of the speed of light. The other fission daughter is absorbed by the sail, depositing its momentum into the sail and causing the sail (and the rest of the ship) to accelerate.

The concept relies, as Jackson said in a recent email, on using antimatter as a spark plug rather than as a fuel, converting the energy from proton-antiproton annihilations into propulsion.

Image: The original antimatter probe concept. Credit: Gerald Jackson/Hbar Technologies.

The current work grows out of a 2002 grant from NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts but the plan is to develop the idea far beyond the Kuiper Belt mission Jackson and Howe initially envisioned. Going interstellar would take not milligrams but tens of grams of antimatter, far beyond today’s infinitesimal production levels. In fact, while the Fermi National Accelerator laboratory has been able to produce no more than 2 nanograms of antimatter per year, even that is high compared to CERN’s output (the only current source), which is 100 times smaller.

Even so, interest in antimatter remains high because of its specific energy — two orders of magnitude larger than fusion and ten orders of magnitude larger than chemical reactions — making further research highly desirable. If the fission reaction the antimatter produces within the sail is viable, we will be able to demonstrate a way to harness those energies, with implications for deep space exploration and the possibility of interstellar journeys.

The original NIAC work led to a sail 5-meters in diameter, with a 15-micron thick carbon layer and a uranium coating 293 microns thick. Interestingly, the study showed that the sail had sufficient area to remove any need for active cooling of the surface. Indeed, the steady-state temperature of the sail would be 570

October 14, 2016

Cosmology: Shelter from the Storm

I had thought while the power was out this past week that I would like to write about cosmology when it came back. That’s because there’s nothing like a prolonged power outage to adjust your perspective. The big picture beckons. In my case, it was thinking about how trivial being out of power was compared to those who had lost so much more in the wake of the recent hurricane.

So thinking about the cosmos became my shelter from the storm. I appreciated the emails from so many of you, but aside from a major chunk of tree that landed on the roof, we did just fine. In fact, it was deeply moving to see people from the neighborhood — some I knew, some I only recognized — turn up to get up on the roof and move that tree. I’m always reminded to do more for the people around me when I see something like this, and apprehensive that my resolution to do so all too often gets put aside as normal life returns.

The Universe We Can See

Reading by candlelight really is wonderful, and I ask myself why I don’t do it more often. There is something about that soft, flickering light on a well-printed page. And I found reading about cosmology by candlelight was especially pleasing, a way of connecting to a past way of life that had its own conceptions about the cosmos. One thing I read was my notes from work just received when the power went, a paper on galactic structure I fortunately printed just in time.

The conclusion of this one is straightforward: There are at least 10 times as many galaxies in the observable universe as previously thought. Christopher Conselice (University of Nottingham, UK) led an international team that produced this result. I was reading about it in a room full of candles and thinking about room after room of candles stretching out into infinity.

That homely thought weds the prosaic and the vast, sort of the way Douglas Adams did in his famous line on the size of the universe in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

“Space is big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist’s, but that’s just peanuts to space.”

I’m sure you’re familiar with the line, but it still raises a chuckle. And this team’s findings cause yet another shift in perspective. Thus Conselice:

“It boggles the mind that over 90% of the galaxies in the Universe have yet to be studied. Who knows what interesting properties we will find when we observe these galaxies with the next generation of telescopes.”

Image: The GOODS South Field (Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey). GOODS draws on observations from the Spitzer, Hubble and Chandra observatories as well as the European Space Agency’s Herschel and XMM-Newton, along with ground-based facilities, to survey the distant universe across the electromagnetic spectrum. Credit: GOODS/Conselice et al.

Before this, we relied on such measures as the Hubble Deep Field images from the 1990s, which helped us arrive at an estimate of between 100 and 200 billion galaxies in the observable universe. Conselice and team studied the matter using Hubble imagery as well as other published data to create a 3D view, estimating the number of galaxies at various times in the history of the cosmos. Their mathematical models pointed to the result, that we have not been able to see most of the galaxies that are out there in our cosmological horizon.

Moreover, the work offers an interesting perspective on galaxies throughout time, one showing how their numbers have changed as the universe evolved. The paper explains that the total number density of galaxies in the universe declines with time:

[The] total number density… declines by a factor of 10 within the first 2 Gyr of the universe’s history, and a further reduction at later times. This decline may further level off between redshifts of z = 1 and z = 2. The star formation rate during this time is also very high for all galaxies, which should in principle bring galaxies which were below our stellar mass limit into our sample at later times. This would naturally increase the number of galaxies over time, but we see the opposite. This is likely due to merging and/or accretion of galaxies when they fall into clusters which are later destroyed through tidal effects, as no other method can reduce the number of galaxies above a given mass threshold.

So what is known as the ‘top-down formation of structure’ in the universe is supported by this work. Most of the galaxies in the first few billion years of the universe were similar in mass to the satellite galaxies we see surrounding the Milky Way. Galactic mergers reduce the total number. And although Conselice and colleagues show us that there are so many galaxies that almost every point in the sky contains part of one, most of these galaxies are invisible not just to the human eye but to our best telescopes.

If that rings a bell, it’s because we’re homing in on Olbers’ paradox, the idea that the darkness of the night sky is in contradiction to the assumption of an infinite universe filled with stars (based on the work of the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers, 1758-1840). Why is the night sky as dark as it is? I won’t get into the details on dust and gas absorption of light that the paper offers, but will simply quote the finding from the Conselice paper:

It would… appear that the solution to the strict interpretation of Olbers’ paradox, as an optical light detection problem, is a combination of nearly all possible solutions – redshifting effects, the finite age and size of the universe, and through absorption.

The paper is Conselice et al., “The Evolution of Galaxy Number Density at z < 8 and its Implications,” to be published in the Astrophysical Journal. Preprint here.

October 11, 2016

Working in the Dark

Hurricane Matthew’s effects continue to be felt in the form of flooding, power outages and downed trees. I’m now told not to expect power for 4-6 days. The situation obviously impacts my ability to post here. I’ll try to keep up with comment moderation when possible. Will get things back to normal whenever the lights come back on.

October 7, 2016

Spiral Density Waves: Clue to Planet Formation?

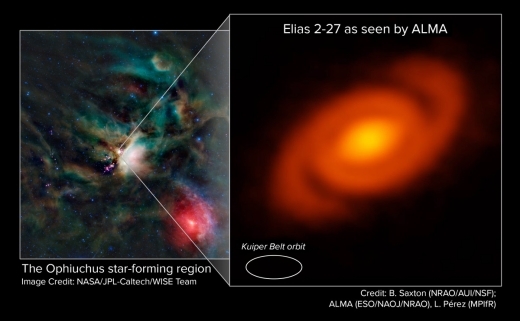

Have a look at the spiral of pinwheeling dust that can be seen around the young star Elias 2-27. We’re looking at gravitational perturbations in a protoplanetary disk that, as this National Radio Astronomy Observatory news release says, mimic the vast arms we expect in a spiral galaxy. But here we’re looking at a process with implications for planet formation, one that draws on data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). This is the first time a spiral density wave has been detected in a protoplanetary disk’s planet formation areas.

Image: ALMA peered into the Ophiuchus star-forming region to study the protoplanetary disk around the young star Elias 2-27. Astronomers discovered a striking spiral pattern in the disk. This feature is the product of density waves – gravitational perturbations in the disk. Credit: L. Pérez (MPIfR), B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF), ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), NASA/JPL Caltech/WISE Team.

Some 450 light years from Earth in the Ophiuchus star-forming region, Elias 2-27 is about half the mass of the Sun, though its protoplanetary disk is massive. Although the young star (about a million years old, according to current estimates) is shrouded by the molecular cloud from which it grew, ALMA was able to peer into the mid-plane of the disk to identify the spiral density waves. The spiral arms extend as much as 10 billion kilometers away from the host star.

All this catches the eye because while we can account for star formation from the collapse of gas and dust under the influence of gravity, we need a mechanism to keep enough material from falling into the protostar to ensure that it doesn’t spin up enough to shred itself. The protostellar disk projects angular momentum outward, and is where we can expect planets to form. But standard core accretion models have problems explaining the formation of planets 20 to 30 AU out, where the disk may not be dense enough to allow the process to be efficient.

Gravitational instabilities in the outer disk, however, can produce the kind of dense spiral arms we see here, with new material being pushed out into regions far from the star and collapsing under its own gravity to begin planet formation. Andrea Isella (Rice University) explains:

“We don’t completely understand how planets form, but we suspect there are two ways: Either small particles stick together until they form something like the Earth or Mars, or accreting gas forms a planet like Saturn or Jupiter. But this process works only very close to the star, within a few astronomical units (roughly the distance from the Sun to the Earth), because that’s where all the material is, and it has to have enough density… If a disk is massive enough to be gravitationally unstable, a spiral will form naturally.”

Thus the spiral arms of Elias 2-27 may be the manifestation of an instability that gives birth to a particular kind of exoplanet. Near to the star, the ALMA observations found a flattened dust disk that extends out beyond 30 AU, followed by a narrow band of sharply diminished dust that may indicate a planet in formation. The spiral arms extend outward from the edge of this gap in the disk. Lead author Laura Pérez (Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy) notes that an upcoming program will use ALMA data to home in on similar protoplanetary disks as we try to find out whether Elias 2-27’s spiral density waves actually do reveal planet(s) in formation.

The paper is Pérez et al., “Spiral density waves in a young protoplanetary disk,” Science Vol. 353, Issue 6307 (30 September 2016), pp. 1519-1521 (abstract). A Rice University news release is also available.

October 6, 2016

Detecting Long-Period Planets & Stellar Companions

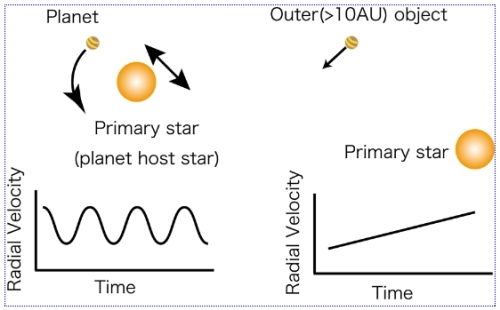

Spotting planets a long way from their stars is no easy proposition when you’re using radial velocity methods. The idea is to track the minute movement of the star as it is affected by an orbiting planet, which shows up as a Doppler shift in the data. What we’re actually seeing is the star and planet orbiting the center of gravity, an indirect method of detection that observes not the planet itself but the effects of the planet as it produces this variation in radial velocity.

The first exoplanets were detected this way, and the method has continued to produce new discoveries. But as a planet’s distance from its star increases, radial velocity becomes tricky to use. Now observation times become extended as the planet completes its longer orbit. We face the same issue with the transit method, which charts the drop in brightness as a planet moves across the face of its star as seen from Earth. Here, too, planets in distant orbits around their star are hard to detect because of the lengthy period of time between individual transits.

Because of these issues, we have little data on the occurrence rate of planets in wide orbits, and that is a problem for analyzing planet formation theories like core accretion, gravitational disk instability and planet migration. The long-term radial velocity data of a host star with a companion object beyond 10 AU shows an almost linear trend over a short observing period. Detection of such a trend is not in itself enough to identify the source of the RV signal.

Image: Periodic change in the radial velocity of the primary star shown left is the strong signature of a planet. When the companion object is far way (farther than 10 AU), the orbital period is so long that the radial velocity shows a linear change, as shown in the right panel. (Credit: NAOJ).

Researchers from the Tokyo Institute of Technology have been trying to solve this problem by combining radial velocity methods with direct imaging. With the latter, the planet detection actually becomes easier as the distance between star and planet widens, because the light of the companion object is not swamped by proximity to the host star. The Tokyo team, using an instrument at Okayama Astrophysical Observatory (NAOJ) has targeted stars 1.5 to 5 times as massive as the Sun, looking not just for long period planets but also companion stars.

A long-term radial velocity trend flags such objects, but it’s the follow-up with direct imaging (in this case using the HiCIAO imager at the Subaru Telescope) that has paid off in an analysis of six intermediate-mass giant stars. All six of these stars showed a long-term radial velocity trend. The question thus becomes, is the source of the trend a companion star or a planet?

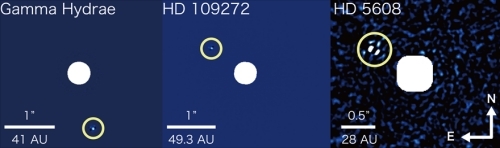

HiCIAO is a coronagraph that masks the light of the primary star to allow detection of fainter objects. Three of the observed stars — γ Hydra, HD 5608, and HS 109272 — show companion stars in this analysis, while around three others — ɩ Draconis, 18 Delphinus, and HD 14067 — companion objects more massive than 60 Jupiter masses can be excluded. The latter are considered candidates for hosting brown dwarfs, while 18 Delphinus is the most likely prospect for hosting a high-mass planet (~ 10-50 AU) that is below the current detection limit.

Image: Objects in the yellow circle were detected by the current study. White circles or round squares show the position of the primary star. The primary was masked during the observation to help the detection of the fainter objects nearby. (Credit: NAOJ)

Combining radial velocity with direct imaging has allowed the team to confirm that the companion objects they found were the cause of the long-term trend in the RV data. On a broader level, these methods may help us understand the distribution of planets around stars more massive than the Sun, as the paper on this work notes:

At Okayama Astrophysical Observatory (OAO), an RV survey targeting intermediate-mass giants (1.5–5 M⊙) has been conducted for over a decade (e.g., Sato et al. 2003). Sato et al. (2008) found that there is a difference between orbits of planets around intermediate-mass stars and around lower-mass FGK stars. Most planets around intermediate-mass stars have a semi-major axis larger than 0.6 AU, while FGK stars have shorter-period planets. Hence, it was suggested that the orbital distribution of exoplanets around intermediate-mass stars is different from that around solar-type stars.

Is the suggestion valid, or simply the result of our limited datasets? The paper continues:

In addition, the OAO survey detected long-term RV trends in several targets, which indicates the presence of distant companions around them… Identifying the companions that generate the RV trend can improve our knowledge of exoplanet populations for intermediate-mass stars, which are not well understood compared to solar-type stars.

This is not the only study that has combined direct imaging and radial velocity trends. In fact, a project called TRENDS (TaRgetting bENchmark objects with Doppler Spectroscopy), led by Justin Crepp (Notre Dame) has detected three low-mass stellar companions using these methods, along with a white dwarf and a brown dwarf companion, working with data on host stars ranging from F-class down to M-dwarfs. Clearly, direct imaging can be a benefit as we try to work out the source of RV trends that point to the existence of a distant companion.

The paper is Ryu et al., “High-contrast Imaging of Intermediate-mass Giants with Long-term Radial Velocity Trends,” Astrophysical Journal Vol. 825, No. 2 (12 July 2016). Abstract / preprint.

October 5, 2016

On Outer System Oceans

Back in the days when I was reading Poul Anderson’s The Snows of Ganymede and thought of the moons of Jupiter as icy wastelands, I never would have dreamed there could be an ocean below their surfaces. But now we have oceans proliferating. Ganymede’s may contain more water than all Earth’s oceans, while Callisto is also in the mix, and we’ve known about Europa for some time now. At Saturn, the case for an ocean inside Titan seems strong, while Enceladus continues to spark mission proposals to study its frequent geysers.

If you’re a Centauri Dreams regular, you know that we’ve talked about Pluto’s oceanic possibilities for some time, now strengthened in new work from Brandon Johnson (Brown University). Johnson and colleagues have modeled an ocean layer on Pluto more than 100 kilometers thick, with a salt content more or less like that of the Dead Sea on Earth. Johnson focused on Sputnik Planum, the 900-kilometer basin that comprises part of the heart-shaped feature we all learned to recognize during last summer’s New Horizons flyby.

The work is helpful because unlike previous studies, it puts constraints on the depth of the ocean and offers information about its composition. Sputnik Planum, as it turns out, sits exactly on the tidal axis linking tidally-locked Charon with Pluto, suggesting that the area has a positive mass anomaly; i.e., there is more mass here than the average for Pluto’s crust.

Thus Charon’s gravity would eventually pull this higher-mass area into the alignment we see. A large impact, like the one that created Sputnik Planum, would eventually be filled with liquid water, and in Johnson’s scenario, nitrogen ice deposited later would tip the scales, creating the positive mass anomaly. “This scenario, says Johnson, “requires a liquid ocean.” And of the various thicknesses of the water layers modeled, 100 kilometers works out best at creating the features we see at Sputnik Planum.

Usefully, the team’s computer models showed that the thickness of the ocean layer could be tied directly to the production of the mass anomaly, which also turns out to be sensitive to the salinity of the water, affecting the water’s density. We can tell a lot from this impact of an object 200 kilometers across or larger and its effects upon an ocean with a salinity of about 30 percent.

“What this tells us is that if Sputnik Planum is indeed a positive mass anomaly —and it appears as though it is — this ocean layer of at least 100 kilometers has to be there,” Johnson says. “It’s pretty amazing to me that you have this body so far out in the solar system that still may have liquid water.”

The Case for Dione

Now we have word of yet another possible ocean, this one on Saturn’s moon Dione. Mikael Beuthe (Royal Observatory of Belgium) and team have been modeling the icy shells of Enceladus and Dione, using gravity data from Cassini flybys. The models study the shells of both moons as global icebergs immersed in water — here surface peaks are held up by a large mass under the water. The approach has not previously proven effective in modeling Enceladus, for it produces a thick crust for the moon that is inconsistent with our observations.

But isostasy, the equilibrium in parts of the Earth’s crust, can be similarly modeled, as blocks floating on the underlying mantle, which rises and falls as material is added or removed. What the researchers have done is to add a new wrinkle:

“As an additional principle, we assumed that the icy crust can stand only the minimum amount of tension or compression necessary to maintain surface landforms,” says Beuthe. “More stress would break the crust down to pieces.”

This revised model works well at producing an ocean for Enceladus under a thinner crust than previous models, with water close enough to the surface to produce the famous geysers at the south pole. The model is also consistent with the libration of Enceladus in its orbit, oscillations that would be smaller if the moon had a thicker crust. Under the same model, Dione is revealed to have a much thicker crust covering a deep ocean between the crust and the moon’s core.

The Cassini data thus become consistent with an ocean about 100 kilometers below the surface of Dione, an ocean perhaps tens of kilometers deep surrounding a large, rocky core. We may be able to test this prediction with future spacecraft in the Saturn system, which may be able to measure the libration of Dione, an oscillation the researchers believe would be well below the detection capabilities of Cassini, but a useful marker as evidence of the subsurface ocean.

Image: Dione with Enceladus in the background. This image was taken by the Cassini spacecraft on 8 September 2015. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

And what of other outer system objects? From the paper:

Beyond Enceladus and Dione, our new take on isostasy is applicable to large icy satellites

with global oceans, such as Europa [Nimmo et al., 2007b], Titan [Nimmo and Bills,2010], and particularly Ganymede whose gravity and shape will be measured by the JUICE mission. According to Park et al. [2016], gravity and shape data from the Dawn mission suggest isostasy on Ceres, but the case is far from clear because compensation does not occur for all gravity components. Finally, isostasy plays a crucial role in understanding the long-wavelength gravity and shape as well as estimating the crust thickness of the planets Mars [Wieczorek and Zuber , 2004], Venus [James et al., 2013], and Mercury [Perry et al., 2015]. Thanks to the simultaneous availability of gravity/shape and libration data, Enceladus’s case constitutes the first validation of planetary-scale isostasy.

The paper is Beuthe et al., “Enceladus’ and Dione’s floating ice shells supported by minimum stress isostasy,” published online by Geophysical Research Letters 28 September 2016 (abstract / preprint). The paper on Pluto’s ocean is Johnson et al., “Formation of the Sputnik Planum basin and the thickness of Pluto’s subsurface ocean,” Geophysical Research Letters 19 September 2016 (abstract).

October 4, 2016

System Evolution: Delving into Brown Dwarf Disks

We’ve seen circumstellar disks around numerous stars, significant because it is from such disks that planets are formed, and we would like to know a good deal more about how this process works. Now we have word of planet-forming disks around several low-mass objects that fit into the brown dwarf range, and one small star about a tenth the mass of the Sun. With the brown dwarfs, we’re working with objects small enough to be at the boundary between planet and star.

The work is led by Anne Boucher (Université de Montréal), whose team drew photometric data from the Two-Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) and the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission, allowing the detection of the objects at infrared wavelengths. Boucher notes the strong attraction such objects hold for astronomers:

“Finding disks in low-mass systems is really interesting to us, because objects that exist at the lower limit of what defines a star and that still have disks that indicate planet formation can tell us a lot about both stellar and planetary evolution.”

Image: An artist’s conception of a planet-forming disk around a brown dwarf. Credit: Robin Dienel.

But let’s pause for a moment on the nature of the disks themselves. Dusty debris disks are considered to be signs of past planet formation, while gas-rich primordial disks mark the presence of active planet formation and accretion into the host star. Because disks can be detected by the presence of excess infrared, beyond what we would expect from the star by itself, we can use infrared observations to measure the differences in thermal emission from one infant system to another, showing us a range of disks at various stages of their evolution.

Thus we get massive primordial disks that are gas-rich and dense around younger systems, while dusty debris disks are colder and more depleted in gas, marking the remnants of planetary system formation even as they are replenished by the collisions of small objects in the system. These can last up to 100 million years; they’re colder and observable in the mid-infrared (primordial disks produce a strong signature in the near-infrared). We also see so-called ‘transition’ disks with an inner region depleted of dust, and an outer region still rich in it.

What Boucher and colleagues have been looking at are three objects ranging from 13 to 19 Jupiter masses, and a fourth of between 101 and 138 Jupiter masses. The paper makes the case that all four disk candidate stars are members of stellar associations — the TW Hydra, Columba, and Tucana-Horologium associations — allowing the researchers to draw conclusions about their age. A stellar association is a large grouping of stars similar in spectral type and origin, grouped more loosely than open or globular-type star clusters. These are young stars that have not had time to move any great distance from their place of formation.

The four disks are all thought to be in the planet-forming phase, none of them having attained the age of a dusty debris disk. Even so, two of these objects appear older — at between 42 and 45 million years — than we would normally associate with an active disk system. From the paper:

Disk temperatures and fractional luminosities were determined from this analysis. Their values indicate that the new disks are likely transitional or primordial. The spectral types of these new disk hosts are late (M4.5 to L0δ), and correspond to low-mass BDs (13 − 19 and 101 − 138MJup) of young ages (∼ 7 − 13 and ∼ 38 − 49Myr). These four systems join a relatively small sample of low-mass objects known to harbor a circumstellar disk. There is still a lot to learn about primordial and (pre-)transitional disks around low-mass stars, and these four new candidates could play an important role to shed light on the formation and evolution processes of stars and planetary systems.

Also in question is the fraction of brown dwarfs that have developed planetary systems. Finding debris disks around young objects like these is one way into the problem, for we can watch the process of planet formation unfold around objects of different ages. Bear in mind as well that their lower luminosity means objects like these could be interesting targets for exoplanet searches using direct imaging methods. All four of the new disk candidates should likewise be prime candidates, the paper suggests, for the Atacama Large Millimeter Array.

The paper is Boucher et al., “BANYAN. VIII. New Low-Mass Stars and Brown Dwarfs with Candidate Circumstellar Disks,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Paul Gilster's Blog

- Paul Gilster's profile

- 7 followers