Boria Sax's Blog: Told Me by a Butterfly, page 6

March 17, 2014

J. J. Grandville and His Fantastic Creatures

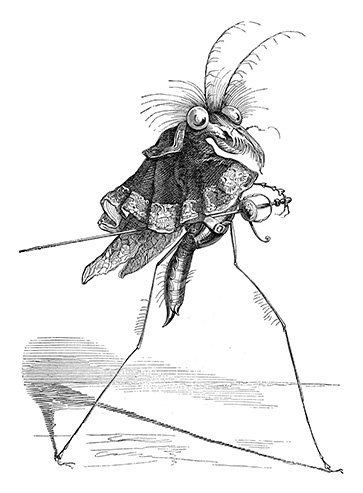

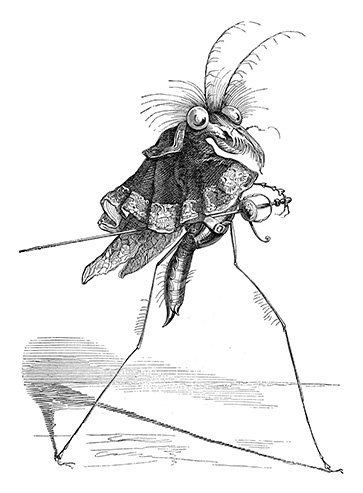

In Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux (The Private and Public Lives of Animals), first published in 1842, Animals of the world decide to do away with human oppression, and assemble a parliament on the site of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. All are delirious with joy, but, as they embrace, ". . . a duck was strangled by an overjoyed fox, a sheep by an enthusiastic wolf, and a horse by a delirious tiger." Many tales follow in which insects, reptiles and mammals make grandiloquent speeches, fight duels, and fall in love. But there is something the beasts are hiding, and only the pictures tell . . . . the animals are really humans in disguise!

J. J. Grandville, the illustrator, was not a politician or philosopher but a storyteller and even, arguably, the inventor of the graphic novel. In most of his books, the printed words do little more than summarize a story, and the pictures really tell it. They give new dimensions to what might otherwise be stereotypes. People are bestial while animals are human. Comic characters are sad, and tragic ones are funny. Nothing is ever what you expected.

Grandville generally preferred not mammals, which might have seemed a bit too "human" to him, or even birds but reptiles, amphibians, insects, arachnids, invertebrates, plants and machines as characters in his dramas. His animals dress in human clothing not to reveal their basic humanity but, rather, their (and our) essential strangeness.

Very few other artists have been able to fuse human and bestial features so completely, to a point where it is impossible to say which is prior. Animals, even plants and machines, in his work, share the human capacity for corruption, yet perhaps that is just another way of saying human beings share their innocence.

Here are a few of his illustrations, accompanied by brief notes and commentaries (Viewing this full screen is recommended, since the detail is often quite fine.):

The misocamp, from Grandville's Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux

J. J. Grandville, the illustrator, was not a politician or philosopher but a storyteller and even, arguably, the inventor of the graphic novel. In most of his books, the printed words do little more than summarize a story, and the pictures really tell it. They give new dimensions to what might otherwise be stereotypes. People are bestial while animals are human. Comic characters are sad, and tragic ones are funny. Nothing is ever what you expected.

Grandville generally preferred not mammals, which might have seemed a bit too "human" to him, or even birds but reptiles, amphibians, insects, arachnids, invertebrates, plants and machines as characters in his dramas. His animals dress in human clothing not to reveal their basic humanity but, rather, their (and our) essential strangeness.

Very few other artists have been able to fuse human and bestial features so completely, to a point where it is impossible to say which is prior. Animals, even plants and machines, in his work, share the human capacity for corruption, yet perhaps that is just another way of saying human beings share their innocence.

Here are a few of his illustrations, accompanied by brief notes and commentaries (Viewing this full screen is recommended, since the detail is often quite fine.):

The misocamp, from Grandville's Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux

Published on March 17, 2014 12:21

March 14, 2014

Saint Patrick's Day and the Other American Dream

It is now only a short time until Saint Urho's Day, named after the holy man who drove the grasshoppers out of Finland. Actually, Urho turns out to be a fabrication of Finnish-Americans living in Minnesota during the 1950s, but his day is still celebrated with parades, ethnic costumes, and even green beer. It is set on March 16th, the day before Saint Patrick's Day, but, since local communities celebrate both of these festivities at different times, the official date hardly matters at all.

The festivity obviously turns Patrick into Urho, Ireland into Finland, and snakes into grasshoppers. Maybe Patrick is filing a lawsuit in heaven, but here on earth nobody really cares. Mexican-Americans have also appropriated Saint Patrick's day, which they include in the Catholic calendar. It often is an occasion to honor the San Patricios, battalions of Catholic, largely Irish, Americans that switched sides in the Mexican War, and then fought with legendary courage.

But Saint Patrick's Day is not really about history, religion, or even Ireland; it is about the "other" American dream. Like the dream of building a new and better life, this one is a product of the immigrant experience. It is the nostalgic dream, the longing for a life that was left behind, for all the things that might have been, or might have happened, if one had only stayed. This is particularly intense among the Irish, since their departure from home was often not fully voluntary, their numbers great, and their initial experience in the New World very difficult. But, for the most part, the country of origin could just as well be Finland, Mexico, or anywhere else.

The saint himself is a semi-historical character, but popular images of him have little to do with the fifth-century mystic. The celebration is a pastiche of all the wonderful things that people in America think they might have missed by sailing to the New World: passionate faith, rowdiness, folklore, community, tradition... It has a way of transforming everything, including anti-Irish stereotypes, into fun. But the heavy drinking points to an undertone of sadness that accompanies the merriment, a bit like the many Irish songs in which mournful lyrics are set to rollicking melodies.

According to legend, Saint Patrick drove the snakes out of Ireland, but that place -- like Iceland and New Zealand -- never had any. Countless gods, heroes and saints in Western culture have been known for killing serpents or dragons; Apollo, Cadmus, Perseus, Sigurd, Beowulf, Saint George, and Saint Margaret are just a few of the best known. Saint Patrick belongs in this tradition, but what sets him apart is his lack of violence. He never kills or even threatens the serpents, but, rather, negotiates their departure, with a mixture of humor, persuasion, and occasional trickery. Over the years, particularly outside of Ireland, the snakes have gone from being an adversary to a sort of totem, and the holy man is often shown with serpents at his side. This is like the original Eden where, according to legend, the animals talked like human beings.

Ireland has been idealized almost beyond recognition, as a magical land of leprechauns and fairies. Perhaps Patrick represents the original Adam, while Ireland, the pagan goddess Éire, is his Eve. This time around, the first man asked the serpent to leave, so they could live happily forever.

Happy Saint Patrick's Day!

The festivity obviously turns Patrick into Urho, Ireland into Finland, and snakes into grasshoppers. Maybe Patrick is filing a lawsuit in heaven, but here on earth nobody really cares. Mexican-Americans have also appropriated Saint Patrick's day, which they include in the Catholic calendar. It often is an occasion to honor the San Patricios, battalions of Catholic, largely Irish, Americans that switched sides in the Mexican War, and then fought with legendary courage.

But Saint Patrick's Day is not really about history, religion, or even Ireland; it is about the "other" American dream. Like the dream of building a new and better life, this one is a product of the immigrant experience. It is the nostalgic dream, the longing for a life that was left behind, for all the things that might have been, or might have happened, if one had only stayed. This is particularly intense among the Irish, since their departure from home was often not fully voluntary, their numbers great, and their initial experience in the New World very difficult. But, for the most part, the country of origin could just as well be Finland, Mexico, or anywhere else.

The saint himself is a semi-historical character, but popular images of him have little to do with the fifth-century mystic. The celebration is a pastiche of all the wonderful things that people in America think they might have missed by sailing to the New World: passionate faith, rowdiness, folklore, community, tradition... It has a way of transforming everything, including anti-Irish stereotypes, into fun. But the heavy drinking points to an undertone of sadness that accompanies the merriment, a bit like the many Irish songs in which mournful lyrics are set to rollicking melodies.

According to legend, Saint Patrick drove the snakes out of Ireland, but that place -- like Iceland and New Zealand -- never had any. Countless gods, heroes and saints in Western culture have been known for killing serpents or dragons; Apollo, Cadmus, Perseus, Sigurd, Beowulf, Saint George, and Saint Margaret are just a few of the best known. Saint Patrick belongs in this tradition, but what sets him apart is his lack of violence. He never kills or even threatens the serpents, but, rather, negotiates their departure, with a mixture of humor, persuasion, and occasional trickery. Over the years, particularly outside of Ireland, the snakes have gone from being an adversary to a sort of totem, and the holy man is often shown with serpents at his side. This is like the original Eden where, according to legend, the animals talked like human beings.

Ireland has been idealized almost beyond recognition, as a magical land of leprechauns and fairies. Perhaps Patrick represents the original Adam, while Ireland, the pagan goddess Éire, is his Eve. This time around, the first man asked the serpent to leave, so they could live happily forever.

Happy Saint Patrick's Day!

Published on March 14, 2014 12:11

March 11, 2014

Monkeys and Apes, an Essay in Pictures

The monkey-god Hanuman is beloved in the Hindu pantheon, largely because he is capable of both childish mischief and noble sacrifice. When Hanuman was a child, he looked up, saw the sun and thought it must be a delicious fruit. He jumped to pick it and rose so high that Indira, god of the sky, became angry at the invasion of his domain. Indira hurled a thunderbolt at the intruder, striking Hanuman in the jaw. At this, the father of Hanuman, Vayu, god of winds, became furious, and started a storm that soon threatened to destroy the entire world. Brahma, the supreme god placated Vayu by granting Hanuman invulnerability. Indira then added a promise that Hanuman could choose his own moment of death. Ever since, however, monkeys have swollen jaws. This story, from The Ramayana, an ancient Hindu epic, shows the amusement with which apes have generally been regarded throughout the world. Because Hanuman is a monkey, his divinity does not seem intimidating. In the Hindu Panchantantra and the early Buddhist Jatakas, the ape was one of the more sensible of animals, often a chief advisor to the lion king. People of the Far East regard the playfulness of monkeys and apes as divine serenity, not simple frivolity as in the West.

To find a major simian figure in Western religion, we must go all the way back to Thoth, the baboon-headed god of the ancient Egyptians. Thoth was the scribe to Osiris, ruler of the dead, and inventor of the arts and sciences. Perhaps in those archaic times reading and writing, still novel and full of mystery, appeared more simian than "human." Today, of course, we invoke language, especially writing, to proudly distinguish ourselves from all other creatures.

In the early sixth century BCE, the Carthaginian navigator Hanno led an enormous expedition down the West Coast of Africa. According to his account of the voyage, they sighted a huge mountain called the "chariot of the gods." He and his crew confronted wild men and women covered with hair, which threw stones at them and climbed adroitly up the slopes. Ever since then, people have speculated about whether the "wild men" were people in skins, chimpanzees, baboons or, most likely, gorillas. Similar rumors of wild men have continued to circulate ever since, as mariners in distant lands reported seeing men with the heads of dogs, the feet of goats, their faces on their chests, and many creatures just as strange. Stories of hairy, wild men with clubs were told around the fire and sometimes acted out in medieval pageants.

In Early Modern times, an expansion of maritime trade and exploration took Europeans to exotic corners of the world. Explorers began to discover both the great apes and people of cultures radically different from their own; sorting the former from the latter was not an easy matter. Scientists as well as sailors often conflated orangutans with gorillas and African tribesmen, all of whom were known mostly through fleeting glimpses and rumors. Tribes in West Africa regarded apes as human. Some believed that chimpanzees could speak but chose not to, so that they would not be forced to work. "Orangutan" was initially a Malay word for "wild man." When the Dutch anatomist Nicolaas Tulp dissected a body of an orangutan in 1641, he thought that it was the satyr of classical mythology. A colleague of his, Jacob de Bondt, believed these creatures were "born of the lust of Indonesian women who consort in disgusting lechery with apes."

Explorers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries brought tales back to Europe of apes that lived in huts, foraged in trees and fought with cudgels. According to some accounts from the period, apes ravished human females or made war on human towns. The enormously popular History of Animated Nature published by Oliver Goldsmith during the late eighteenth century reported that in Africa sometimes steal men and women to keep as pets. Visitors to Victorian zoos complained that the apes tried to seduce human women. Sometimes apes were even made to put on clothes.

Just as the process of distinguishing apes and men was nearly complete, Darwin developed his Theory of Evolution with The Origin of Species in 1859. Not everyone could understand the book, and some thought that Darwin was either blasphemous or crazy. In a famous debate in 1860, Bishop Wilberforce asked Thomas Huxley whether the ape was on his mother's or his father's side of the family. Huxley replied that rather than be descended from a gifted man who mocks scientific discussion, ". . . I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape." His brilliant rhetoric may have won the day, but wisecracks about apes for grandparents were constantly used in the vitriolic debate about evolution. But even the possibility of kinship made apes appear threatening, and popular writers immediately began to depict them as less human but more dangerous.

For the past several years, I have been collecting pictures of simians from the last few centuries, to show the rapid and dramatic changes that they have undergone. They are colorful and occasionally frightening, and, like most depictions of animals, they usually tell us more about the people than the creatures they wished to show. Here are a few, with some brief notes and commentaries:

(The preceding text is loosely adapted from my book The Mythical Zoo: Animals in Myth, Legend, and Literature. Most, though not all, of the pictures have not been published in recent times.)

The Mythical Zoo: Animals in Myth, Legend and Literature

by Boria Sax

Imaginary Animals: The Monstrous, the Wondrous and the Human

by Boria Sax

To find a major simian figure in Western religion, we must go all the way back to Thoth, the baboon-headed god of the ancient Egyptians. Thoth was the scribe to Osiris, ruler of the dead, and inventor of the arts and sciences. Perhaps in those archaic times reading and writing, still novel and full of mystery, appeared more simian than "human." Today, of course, we invoke language, especially writing, to proudly distinguish ourselves from all other creatures.

In the early sixth century BCE, the Carthaginian navigator Hanno led an enormous expedition down the West Coast of Africa. According to his account of the voyage, they sighted a huge mountain called the "chariot of the gods." He and his crew confronted wild men and women covered with hair, which threw stones at them and climbed adroitly up the slopes. Ever since then, people have speculated about whether the "wild men" were people in skins, chimpanzees, baboons or, most likely, gorillas. Similar rumors of wild men have continued to circulate ever since, as mariners in distant lands reported seeing men with the heads of dogs, the feet of goats, their faces on their chests, and many creatures just as strange. Stories of hairy, wild men with clubs were told around the fire and sometimes acted out in medieval pageants.

In Early Modern times, an expansion of maritime trade and exploration took Europeans to exotic corners of the world. Explorers began to discover both the great apes and people of cultures radically different from their own; sorting the former from the latter was not an easy matter. Scientists as well as sailors often conflated orangutans with gorillas and African tribesmen, all of whom were known mostly through fleeting glimpses and rumors. Tribes in West Africa regarded apes as human. Some believed that chimpanzees could speak but chose not to, so that they would not be forced to work. "Orangutan" was initially a Malay word for "wild man." When the Dutch anatomist Nicolaas Tulp dissected a body of an orangutan in 1641, he thought that it was the satyr of classical mythology. A colleague of his, Jacob de Bondt, believed these creatures were "born of the lust of Indonesian women who consort in disgusting lechery with apes."

Explorers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries brought tales back to Europe of apes that lived in huts, foraged in trees and fought with cudgels. According to some accounts from the period, apes ravished human females or made war on human towns. The enormously popular History of Animated Nature published by Oliver Goldsmith during the late eighteenth century reported that in Africa sometimes steal men and women to keep as pets. Visitors to Victorian zoos complained that the apes tried to seduce human women. Sometimes apes were even made to put on clothes.

Just as the process of distinguishing apes and men was nearly complete, Darwin developed his Theory of Evolution with The Origin of Species in 1859. Not everyone could understand the book, and some thought that Darwin was either blasphemous or crazy. In a famous debate in 1860, Bishop Wilberforce asked Thomas Huxley whether the ape was on his mother's or his father's side of the family. Huxley replied that rather than be descended from a gifted man who mocks scientific discussion, ". . . I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape." His brilliant rhetoric may have won the day, but wisecracks about apes for grandparents were constantly used in the vitriolic debate about evolution. But even the possibility of kinship made apes appear threatening, and popular writers immediately began to depict them as less human but more dangerous.

For the past several years, I have been collecting pictures of simians from the last few centuries, to show the rapid and dramatic changes that they have undergone. They are colorful and occasionally frightening, and, like most depictions of animals, they usually tell us more about the people than the creatures they wished to show. Here are a few, with some brief notes and commentaries:

(The preceding text is loosely adapted from my book The Mythical Zoo: Animals in Myth, Legend, and Literature. Most, though not all, of the pictures have not been published in recent times.)

The Mythical Zoo: Animals in Myth, Legend and Literature

by Boria Sax

Imaginary Animals: The Monstrous, the Wondrous and the Human

by Boria Sax

Published on March 11, 2014 15:31

February 19, 2014

Higher Education and the Poetry of Ideas

Poets and fiction writers used to pride themselves on being, as befitting romantic renegades, outside of academia. They insisted that creative writing was not a teachable subject, since it required a special gift of imagination and a uniquely individual style. Phrases such as "workshop poems" and "academic poems," designating the sort of work allegedly written for classes, were often terms of derision.

That changed in the 1970s with a profusion of new creative writing programs at colleges and universities. Many poets protested vehemently against the institutionalization of their art, but even the most intense critics of creative writing classes usually welcomed a chance to teach one. The sad and simple truth was that poets had nowhere else to go. I knew several local literary legends, and even nationally prominent poets, who published prolifically, yet barely survived on meagre pensions, in one-room apartments infested with insects. Creative writing programs were a means, and probably the only one available, to send at least a little money their way.

Writers became less like shamans, dispensing divine wisdom, than priests, in the employment of a church. They would henceforth be evaluated rather like other academic employees -- by the number of their publications and the prestige of their degrees. Almost nobody realized it at first, but this was part of a process that post structuralists would soon call "decentering the author."

Today the legitimacy of creative writing classes is pretty much unchallenged, and they are close to the center of many academic programs in English. But the study literature itself has changed, perhaps restoring a bit of the status poets and other writers once enjoyed. Until around the middle 1970s, literature was considered the "holistic" discipline, the specialty for people who did not want to specialize. Writing about literature entailed no systematic methodology and no more than a minimum of jargon. Literature was, essentially, a lens through which one might contemplate experience, in a leisurely, unstructured way.

The end of the decade saw the emergence of approaches such as neo-Marxism, postmodernism, deconstruction, Lacanian psychology and new historicism. The study of literature was increasingly professionalized. Students would specialize less by period or author than by methodology, and their scholarship was pervaded by esoteric concepts. The holistic model continued, however, under the heading of "creative writing." What had once been the study of literature became known as "creative non-fiction," and enjoyed prestige comparable to that of fiction or poetry.

Actually, poetry was not quite the last subject to fall under the jurisdiction of academia. There was still one thing that professors never taught, and that was, ironically, how to teach college. Professors had once relied on observation, intuition and, like the poets, a mystique. Just as quite a few poets of the 1960s took advantage of the lack of standards to pass anything which popped into their minds off as verse; some professors would arrive in class late, and then spend what remained of the period talking about their personal problems. But, like the better poets, some professors also developed fascinating, and highly individual, classroom styles.

What we are now seeing might be called "decentering the professor." Now college teaching is becoming a formal academic subject, just like poetry did a few decades ago. The impetus for this change comes largely from new classroom technologies. The complex dynamics of an online or blended classroom make teaching into an activity that simply cannot be accomplished, even poorly, without extensive reflection and careful preparation.

In poetry, the imposition of academic standards may have filtered out the most thoughtless work, which often consisted of hardly more than random phrases and slogans strung together. Nevertheless, even those poets most at home in academia will seldom claim that creative writing programs have improved the quality of American literature. For the most part, poets and novelists have become both less idiosyncratic and less ambitious.

And will the "professionalization" of college teaching lead to an improvement, especially in the relatively traditional classrooms? Or will professors and students, in following increasingly intricate guidelines, lose the excitement of discovery? Will academia, deprived of its mystique, find it has also lost its purpose, even its soul? Will scholarship move outside the academy? Will the new classroom dynamics in some way revive old ideals? Will they generate new ones? We must wait a while for more than tentative answers to such questions, but ours is an exciting time to be a teacher.

The Mythical Zoo by Boria Sax.

That changed in the 1970s with a profusion of new creative writing programs at colleges and universities. Many poets protested vehemently against the institutionalization of their art, but even the most intense critics of creative writing classes usually welcomed a chance to teach one. The sad and simple truth was that poets had nowhere else to go. I knew several local literary legends, and even nationally prominent poets, who published prolifically, yet barely survived on meagre pensions, in one-room apartments infested with insects. Creative writing programs were a means, and probably the only one available, to send at least a little money their way.

Writers became less like shamans, dispensing divine wisdom, than priests, in the employment of a church. They would henceforth be evaluated rather like other academic employees -- by the number of their publications and the prestige of their degrees. Almost nobody realized it at first, but this was part of a process that post structuralists would soon call "decentering the author."

Today the legitimacy of creative writing classes is pretty much unchallenged, and they are close to the center of many academic programs in English. But the study literature itself has changed, perhaps restoring a bit of the status poets and other writers once enjoyed. Until around the middle 1970s, literature was considered the "holistic" discipline, the specialty for people who did not want to specialize. Writing about literature entailed no systematic methodology and no more than a minimum of jargon. Literature was, essentially, a lens through which one might contemplate experience, in a leisurely, unstructured way.

The end of the decade saw the emergence of approaches such as neo-Marxism, postmodernism, deconstruction, Lacanian psychology and new historicism. The study of literature was increasingly professionalized. Students would specialize less by period or author than by methodology, and their scholarship was pervaded by esoteric concepts. The holistic model continued, however, under the heading of "creative writing." What had once been the study of literature became known as "creative non-fiction," and enjoyed prestige comparable to that of fiction or poetry.

Actually, poetry was not quite the last subject to fall under the jurisdiction of academia. There was still one thing that professors never taught, and that was, ironically, how to teach college. Professors had once relied on observation, intuition and, like the poets, a mystique. Just as quite a few poets of the 1960s took advantage of the lack of standards to pass anything which popped into their minds off as verse; some professors would arrive in class late, and then spend what remained of the period talking about their personal problems. But, like the better poets, some professors also developed fascinating, and highly individual, classroom styles.

What we are now seeing might be called "decentering the professor." Now college teaching is becoming a formal academic subject, just like poetry did a few decades ago. The impetus for this change comes largely from new classroom technologies. The complex dynamics of an online or blended classroom make teaching into an activity that simply cannot be accomplished, even poorly, without extensive reflection and careful preparation.

In poetry, the imposition of academic standards may have filtered out the most thoughtless work, which often consisted of hardly more than random phrases and slogans strung together. Nevertheless, even those poets most at home in academia will seldom claim that creative writing programs have improved the quality of American literature. For the most part, poets and novelists have become both less idiosyncratic and less ambitious.

And will the "professionalization" of college teaching lead to an improvement, especially in the relatively traditional classrooms? Or will professors and students, in following increasingly intricate guidelines, lose the excitement of discovery? Will academia, deprived of its mystique, find it has also lost its purpose, even its soul? Will scholarship move outside the academy? Will the new classroom dynamics in some way revive old ideals? Will they generate new ones? We must wait a while for more than tentative answers to such questions, but ours is an exciting time to be a teacher.

The Mythical Zoo by Boria Sax.

Published on February 19, 2014 14:34

February 12, 2014

The First Valentine

Saint Valentine's Day is one of many holidays that are clustered around the beginning of spring, including the Roman Lupercalia, the Celtic Imbolic, the Chinese New Year, Candlemas, Saint Bridget's Day, Groundhog Day, and Saint Patrick's Day, as well as innumerable regional festivities. Just about all are associated in some way with fertility and with new beginnings. Historically, it is not always easy to separate these festivals, since they have repeatedly been moved in the calendar, borrowing customs from one another in the process.

Saint Valentine's Day began to emerge as a distinct celebration around the end of the Middle Ages, as it emerged out of courtly love. Even by comparison with hundreds of other saints in the Christian calendar, Saint Valentine is obscure. There were a few Christian martyrs with the melodious name "Valentine," and it is even uncertain which one the holiday is named for. According to some legends, he was a priest who defied the Roman Emperor by marrying Christians.

In Geoffrey Chaucer's Parliament of Fowles (c. 1382), Saint Valentine's Day is celebrated on the day birds choose their mates. Doves and other "lovebirds" remain an important part of the iconography of Saint Valentine's Day. The custom of exchanging tokens of love might have originated from the mementos given by ladies to the knights who would joust in their honor, which were often detachable sleeves from a garment that the knight could place on his lance, but might be almost anything.

The stylized heart that decorates our valentines today bears little resemblance to any anatomical organ. Its shape is more suggestive of a leaf such as that of a water lily. Toward the end of the Middle Ages, around the same time as Saint Valentine's Day was becoming established, the geometric design was colored red and used to represent the core of passion in human beings. It gained popularity in the Victorian era, when exchanging valentines became very widespread.

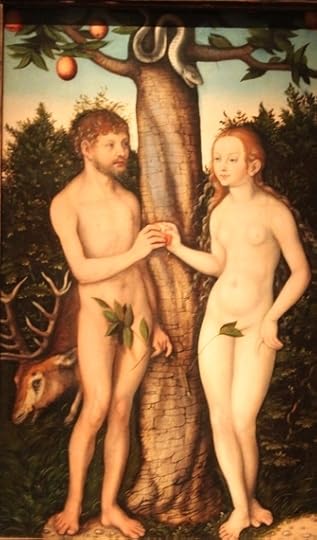

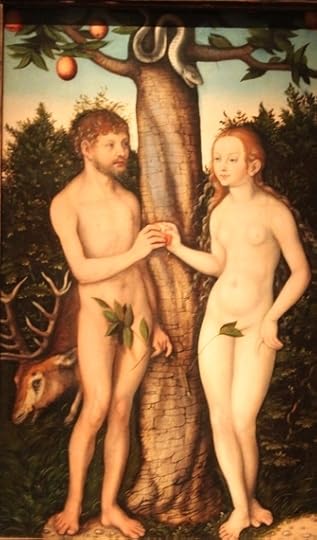

More than anything else, the "hearts" that decorate our valentines suggest an apple, such as the one Eve hands to Adam in pictures, especially from the Middle Ages and Renaissance, of the Garden of Eden. Archeologists have pointed out that apples are not indigenous to the ancient Near East, so the fruit referred to in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve would most likely have been a citron, fig, or pomegranate. In Western iconography, however, it was almost invariably an apple, probably because the Latin word "malus" can mean both "apple" and "evil."

The story of the Garden of Eden has a sort of fairy-tale ambiance that seems to set it apart from the rest of the Bible. This is reflected in the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic tradition which holds that in Paradise all animals could speak like human beings. Apart from Baalam's ass, which is really just the mouthpiece of an angel, the serpent of Eden is the only talking animal in the sacred text.

The story seems to belong to a sort of time before time, to the "once upon a time..." of fairy tales. Tradition softened the harsh ending, which was called a "fortunate fall," necessary for the salvation of humankind, and the couple were honored in the Middle Ages as saints. At least on Valentine's Day, they can "live happily ever after."

Lucas Cronach the Elder, "Adam and Eve," 1528

Saint Valentine's Day began to emerge as a distinct celebration around the end of the Middle Ages, as it emerged out of courtly love. Even by comparison with hundreds of other saints in the Christian calendar, Saint Valentine is obscure. There were a few Christian martyrs with the melodious name "Valentine," and it is even uncertain which one the holiday is named for. According to some legends, he was a priest who defied the Roman Emperor by marrying Christians.

In Geoffrey Chaucer's Parliament of Fowles (c. 1382), Saint Valentine's Day is celebrated on the day birds choose their mates. Doves and other "lovebirds" remain an important part of the iconography of Saint Valentine's Day. The custom of exchanging tokens of love might have originated from the mementos given by ladies to the knights who would joust in their honor, which were often detachable sleeves from a garment that the knight could place on his lance, but might be almost anything.

The stylized heart that decorates our valentines today bears little resemblance to any anatomical organ. Its shape is more suggestive of a leaf such as that of a water lily. Toward the end of the Middle Ages, around the same time as Saint Valentine's Day was becoming established, the geometric design was colored red and used to represent the core of passion in human beings. It gained popularity in the Victorian era, when exchanging valentines became very widespread.

More than anything else, the "hearts" that decorate our valentines suggest an apple, such as the one Eve hands to Adam in pictures, especially from the Middle Ages and Renaissance, of the Garden of Eden. Archeologists have pointed out that apples are not indigenous to the ancient Near East, so the fruit referred to in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve would most likely have been a citron, fig, or pomegranate. In Western iconography, however, it was almost invariably an apple, probably because the Latin word "malus" can mean both "apple" and "evil."

The story of the Garden of Eden has a sort of fairy-tale ambiance that seems to set it apart from the rest of the Bible. This is reflected in the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic tradition which holds that in Paradise all animals could speak like human beings. Apart from Baalam's ass, which is really just the mouthpiece of an angel, the serpent of Eden is the only talking animal in the sacred text.

The story seems to belong to a sort of time before time, to the "once upon a time..." of fairy tales. Tradition softened the harsh ending, which was called a "fortunate fall," necessary for the salvation of humankind, and the couple were honored in the Middle Ages as saints. At least on Valentine's Day, they can "live happily ever after."

Lucas Cronach the Elder, "Adam and Eve," 1528

Published on February 12, 2014 11:32

February 4, 2014

Were the Doves Wise or Foolish?

About a decade or so ago, Pope John Paul II ceremoniously released a dove from the window of the Vatican Palace, which flew out for only a few seconds and immediately returned. The Pope said nothing, but smiled in his wise, but weary way. As a Catholic from Communist-ruled Poland, he was a canny survivor, and doubtless understood what hazards a domesticated dove might face in the wild.

On January 26, 2014, the saintly Pope Francis I sat at a window in front of a crowd of thousands at a window in Ukraine, appealing for peace. When he was finished, two children at his side released two doves of peace, which were immediately attacked by a seagull and a hooded crow. The doves managed to struggle free and fly away, possibly injured, but still vigorous. Since anything associated with the Pope seems especially important, people speculated, usually with a bit of humor, that the incident might presage a coming apocalypse.

The dove was once closely associated with many Mediterranean goddesses such as the Canaanite Asherah, the Babylonian Ishtar and the Greek Aphrodite. According to legend, the Assyrian Queen Semiramis was raised by doves. The Biblical Noah released a dove from his ark, and, when it returned bearing an olive branch, he knew that land was near. In Christianity, a dove appeared at the baptism of Jesus, and became a symbol of the Holy Spirit. During the cold war, the dove of peace was a common symbol of peace for organizations devoted to political reconciliation and disarmament.

But precisely the quality that made the doves a symbol of divine purity may have also, taken to an extreme, endangered them when they were released by the Popes. An article in National Geographic explained the attacks on the doves by pointing out that they were bred to be unnaturally white, which made them stand out conspicuously and invited predators.

In the time of Jesus, the dove was the most popular sacrificial animal, especially among the poor who could not afford a sheep or ox. Perhaps, on some unconscious level, the sacrificial paradigm could be at work in the release of doves. The gesture is a bit reminiscent of the "scapegoat," which is sent into the wilderness, bearing the sins of the people, for the demon Azazel (Leviticus 16:8).

But one need not be superstitious to see significance in the events that accompanied release of doves by Pope Francis, since they reflect several contrasts that are constantly played out in our lives ─- domesticity and wildness, freedom and security, innocence and maturity. Because of this, the ceremony becomes more than a lovely, if slightly bland, spectacle. Some animal protection groups criticized the Pope's release of doves for endangering animals that had been bred in captivity and did not know how to forage or cope with predators. I agree with them, but, nevertheless, the doves seem to have managed pretty well so far, and perhaps we can even draw inspiration from their successful escape.

Which has a better life: the dove in a menagerie ─- with a plentiful supply of food, veterinary care, and security from predators ─- or the one in a meadow, which is in perpetual danger, yet free? Was the dove released by Pope John Paul wise or foolish? Were those released by Pope Francis too innocent? Were they brave?

"The Scapegoat" by William Holman Hunt, 1854

On January 26, 2014, the saintly Pope Francis I sat at a window in front of a crowd of thousands at a window in Ukraine, appealing for peace. When he was finished, two children at his side released two doves of peace, which were immediately attacked by a seagull and a hooded crow. The doves managed to struggle free and fly away, possibly injured, but still vigorous. Since anything associated with the Pope seems especially important, people speculated, usually with a bit of humor, that the incident might presage a coming apocalypse.

The dove was once closely associated with many Mediterranean goddesses such as the Canaanite Asherah, the Babylonian Ishtar and the Greek Aphrodite. According to legend, the Assyrian Queen Semiramis was raised by doves. The Biblical Noah released a dove from his ark, and, when it returned bearing an olive branch, he knew that land was near. In Christianity, a dove appeared at the baptism of Jesus, and became a symbol of the Holy Spirit. During the cold war, the dove of peace was a common symbol of peace for organizations devoted to political reconciliation and disarmament.

But precisely the quality that made the doves a symbol of divine purity may have also, taken to an extreme, endangered them when they were released by the Popes. An article in National Geographic explained the attacks on the doves by pointing out that they were bred to be unnaturally white, which made them stand out conspicuously and invited predators.

In the time of Jesus, the dove was the most popular sacrificial animal, especially among the poor who could not afford a sheep or ox. Perhaps, on some unconscious level, the sacrificial paradigm could be at work in the release of doves. The gesture is a bit reminiscent of the "scapegoat," which is sent into the wilderness, bearing the sins of the people, for the demon Azazel (Leviticus 16:8).

But one need not be superstitious to see significance in the events that accompanied release of doves by Pope Francis, since they reflect several contrasts that are constantly played out in our lives ─- domesticity and wildness, freedom and security, innocence and maturity. Because of this, the ceremony becomes more than a lovely, if slightly bland, spectacle. Some animal protection groups criticized the Pope's release of doves for endangering animals that had been bred in captivity and did not know how to forage or cope with predators. I agree with them, but, nevertheless, the doves seem to have managed pretty well so far, and perhaps we can even draw inspiration from their successful escape.

Which has a better life: the dove in a menagerie ─- with a plentiful supply of food, veterinary care, and security from predators ─- or the one in a meadow, which is in perpetual danger, yet free? Was the dove released by Pope John Paul wise or foolish? Were those released by Pope Francis too innocent? Were they brave?

"The Scapegoat" by William Holman Hunt, 1854

Published on February 04, 2014 10:19

January 30, 2014

The Secret of Groundhog Day

Nostalgia and superstition are guilty pleasures, and one time we allow ourselves to indulge in them, albeit with titters of embarrassment, is on Groundhog Day. This comes on February 2, when the groundhogs allegedly come out of their burrows. If they see their shadows, they will be frightened and return, in which case winter will last for another six weeks. Thousands of people gather around the burrows of famous groundhogs, most notably Punxsutawney Phil in Pennsylvania, and newscasters film their ascent. Officials dressed anachronistically in top hats and frock coats mark the occasion with speeches. Should the groundhog decide to stay, they hold him up for the crowd to see. Critics allege that the result is predetermined, or at least manipulated, by heaters that are placed under the ground.

Groundhog Day goes back to societies in which agriculturalists watched for subtle signs such as the migration of birds or the emergence of animals from hibernation to decide on the best times for planting and harvesting. In England, Germany and Ireland, the prophetic animal is a badger rather than a groundhog. At one time, it was probably the bear, a more imposing creature that probably endowed the day with greater dignity. In Lithuania and parts Italy, it has been a snake.

The idea of using animals to predict the weather, or even climate change, is not by any means irrational. Following an old tradition, the Chinese still use goldfish to predict earthquakes. In Italy in 2009, toads in very large numbers were observed leaving their burrows in Acquilla several days before an earthquake, and scientists who have studied this maintain it was probably due to the release of gases caused by seismic activity. Animals such as bears and groundhogs may be very sensitive to subtle changes in the thawing of the soil and other possible signs of spring. But, for traditional farmers, these indications to the changes in the weather were read in the context of many other clues. A bit like the animals themselves, they cultivated an intuitive sensitivity to climate, which almost everyone today has lost. Furthermore, they did not use the emergence of animals from hibernation to predict the weather in vast geographic areas but only in the local community.

Groundhog Day is set on the same day as the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox celebration of Candlemass, when lights are lit to celebrate the presentation of Jesus, "light of the world," in the temple. The slightly nervous laughter that usually accompanies Groundhog Day, may reflect a Protestant mockery of Catholic rituals. But Candlemass itself goes back to the traditional Celtic celebration of Imbolc, the beginning of spring, which was also set in the first days of February.

With irony, and even a little sneering, Groundhog Day celebrates a rural way of life, which we can now barely remember, yet somehow miss. It is a loss we hardly name, yet still feel intensely. Holidays are times set aside to reflect on the meaning of our past, and Groundhog Day, while seemingly trivial, turns out to have a history as old and complex as perhaps as any commemoration that we have.

Our nostalgia will not long be satisfied by a few top hats and campy homilies. Groundhog Day holds a secret, more concealed than any subterranean stove -- the groundhog represents humanity, as we confront a profoundly uncertain future. From time to time, we contemplate our prospects, like the animal emerging from its burrow. If they are too terrifying or confusing, we return to our hole, to watch Survivor on television or surf the net.

Groundhog Day, 2005 (photo: Aaron Silvers)

Groundhog Day goes back to societies in which agriculturalists watched for subtle signs such as the migration of birds or the emergence of animals from hibernation to decide on the best times for planting and harvesting. In England, Germany and Ireland, the prophetic animal is a badger rather than a groundhog. At one time, it was probably the bear, a more imposing creature that probably endowed the day with greater dignity. In Lithuania and parts Italy, it has been a snake.

The idea of using animals to predict the weather, or even climate change, is not by any means irrational. Following an old tradition, the Chinese still use goldfish to predict earthquakes. In Italy in 2009, toads in very large numbers were observed leaving their burrows in Acquilla several days before an earthquake, and scientists who have studied this maintain it was probably due to the release of gases caused by seismic activity. Animals such as bears and groundhogs may be very sensitive to subtle changes in the thawing of the soil and other possible signs of spring. But, for traditional farmers, these indications to the changes in the weather were read in the context of many other clues. A bit like the animals themselves, they cultivated an intuitive sensitivity to climate, which almost everyone today has lost. Furthermore, they did not use the emergence of animals from hibernation to predict the weather in vast geographic areas but only in the local community.

Groundhog Day is set on the same day as the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox celebration of Candlemass, when lights are lit to celebrate the presentation of Jesus, "light of the world," in the temple. The slightly nervous laughter that usually accompanies Groundhog Day, may reflect a Protestant mockery of Catholic rituals. But Candlemass itself goes back to the traditional Celtic celebration of Imbolc, the beginning of spring, which was also set in the first days of February.

With irony, and even a little sneering, Groundhog Day celebrates a rural way of life, which we can now barely remember, yet somehow miss. It is a loss we hardly name, yet still feel intensely. Holidays are times set aside to reflect on the meaning of our past, and Groundhog Day, while seemingly trivial, turns out to have a history as old and complex as perhaps as any commemoration that we have.

Our nostalgia will not long be satisfied by a few top hats and campy homilies. Groundhog Day holds a secret, more concealed than any subterranean stove -- the groundhog represents humanity, as we confront a profoundly uncertain future. From time to time, we contemplate our prospects, like the animal emerging from its burrow. If they are too terrifying or confusing, we return to our hole, to watch Survivor on television or surf the net.

Groundhog Day, 2005 (photo: Aaron Silvers)

Published on January 30, 2014 14:42

January 27, 2014

What Is a 'Mockingjay'?

When first told around the fire, fairy tales like "Cinderella" were entertainment for everyone, and only in the past few centuries have they become the province of children. Something of the sort may be happening to the epic and romance today. From the Epic of Gilgamesh and Homer to Popol Vuh and the Arthurian romances, the epic is essentially a story on a monumental scale. It is about great themes, larger-than-life characters, amazing feats, and enthralling adventures in which the fates of entire peoples are at stake. Such tales risk coming across as unsophisticated or pretentious in the most serious forms of adult literature today, but you find them in the Harry Potter books and, more recently, in Suzanne Collins' trilogy The Hunger Games. Perhaps the reason why the epic survives largely in literature for young people is that their reality often seems so boundless in both threat and promise.

Grand narratives generate similarly transcendent images. As men and women ceased to believe in them during the early modern period, fantastic creatures such as the unicorn and eventually even the dragon became symbols of freedom and transcendence. They were, in a sense, also symbols of revolt, but more spiritual than political. This was the rebellion against pretensions to comprehend and dominate the natural world, as well as to control one's fellow human beings. Simply by existing, even in the imagination, those creatures showed that those in authority were wrong. In the world of the The Hunger Games, the popular trilogy of novels for young people by Suzanne Collins, the "mockingjay" is such a symbol.

Thirteen districts, in what was once the United States, are oppressed by an evil Capitol, which asserts its power by demanding yearly tributes of young men and women for the Hunger Games, gladiatorial contests in which many people are placed in a controlled environment and only one is meant to survive. The Capitol also created jabberjays, birds that would spy on citizens and repeat their conversations, but rebels divined the purpose of the birds and told them lies. The Capitol decided the birds were useless and abandoned them to perish. The jabberjays, showing an unanticipated will to endure, mated with mockingbirds, to create mockingjays. These new birds lacked the ability to remember words, but recalled tunes instead, and then changed them to create new melodies. They would fall silent in the presence of a beautiful human song.

The heroine is a teenage girl named Katniss, who volunteers to take the place of her sister and be a tribute at the Hunger Games. She wears a pin on her lapel with a mockingjay, which becomes a sign of political and military resistance. In the ceremonies leading up to the games, she is dressed by her handlers first in a garment that appears to be of fire, and later as a mockingjay. But, assuming a role as a symbol of revolution, Katniss cannot be herself. Soon, she can no longer tell her own passions from the expectations of others. As she struggles to save the world, Katniss remains in many ways a typical teenager, who must find her own way amid the pressures from the adult world and her peers. While surviving ghastly trials and tribulations, she also worries about clothes, chooses between boyfriends, and learns who her real friends are.

The mockingjay is a variant of the phoenix, a mythological bird that goes back at least to ancient Egypt, and was said to regenerate by burning itself on a pyre. The phoenix has many variants such as the Egyptian bennu, the Russian firebird, the Chinese feng-huang, and the Japanese hoo-hoo. These mythic avians are generally -- though not always -- feminine, associated with the sun, and have long feathers that flow like tongues of flame. Some have beautiful songs that may be echoed by other birds.

The pin that Katniss wears to the Hunger Games is made of gold, and the mockingjay is surrounded by a circle. The crest resembles that of a blue jay, while the long tail is a bit like that of a mocking bird, but both features are characteristic of the phoenix and her folkloric relatives. This image appears as a logo on the covers of the trilogy, and is clearly a phoenix in the sun.

For all the author's artistry, the contrast between Katniss' epic battles and the relatively mundane problems of growing up can occasionally seem a bit humorous. She can indeed become a mockingjay, a phoenix, but not at will or all the time. But, for her at least, maturity resides precisely in that lesson. She is at her best when she forgets the scripts prepared by others and simply does what she feels to be right. Perhaps, in the end, the role of mockingjay is really the epic dimension of normal life.

Traditional image of the feng huang or "Chinese phoenix" from an embroidery

Grand narratives generate similarly transcendent images. As men and women ceased to believe in them during the early modern period, fantastic creatures such as the unicorn and eventually even the dragon became symbols of freedom and transcendence. They were, in a sense, also symbols of revolt, but more spiritual than political. This was the rebellion against pretensions to comprehend and dominate the natural world, as well as to control one's fellow human beings. Simply by existing, even in the imagination, those creatures showed that those in authority were wrong. In the world of the The Hunger Games, the popular trilogy of novels for young people by Suzanne Collins, the "mockingjay" is such a symbol.

Thirteen districts, in what was once the United States, are oppressed by an evil Capitol, which asserts its power by demanding yearly tributes of young men and women for the Hunger Games, gladiatorial contests in which many people are placed in a controlled environment and only one is meant to survive. The Capitol also created jabberjays, birds that would spy on citizens and repeat their conversations, but rebels divined the purpose of the birds and told them lies. The Capitol decided the birds were useless and abandoned them to perish. The jabberjays, showing an unanticipated will to endure, mated with mockingbirds, to create mockingjays. These new birds lacked the ability to remember words, but recalled tunes instead, and then changed them to create new melodies. They would fall silent in the presence of a beautiful human song.

The heroine is a teenage girl named Katniss, who volunteers to take the place of her sister and be a tribute at the Hunger Games. She wears a pin on her lapel with a mockingjay, which becomes a sign of political and military resistance. In the ceremonies leading up to the games, she is dressed by her handlers first in a garment that appears to be of fire, and later as a mockingjay. But, assuming a role as a symbol of revolution, Katniss cannot be herself. Soon, she can no longer tell her own passions from the expectations of others. As she struggles to save the world, Katniss remains in many ways a typical teenager, who must find her own way amid the pressures from the adult world and her peers. While surviving ghastly trials and tribulations, she also worries about clothes, chooses between boyfriends, and learns who her real friends are.

The mockingjay is a variant of the phoenix, a mythological bird that goes back at least to ancient Egypt, and was said to regenerate by burning itself on a pyre. The phoenix has many variants such as the Egyptian bennu, the Russian firebird, the Chinese feng-huang, and the Japanese hoo-hoo. These mythic avians are generally -- though not always -- feminine, associated with the sun, and have long feathers that flow like tongues of flame. Some have beautiful songs that may be echoed by other birds.

The pin that Katniss wears to the Hunger Games is made of gold, and the mockingjay is surrounded by a circle. The crest resembles that of a blue jay, while the long tail is a bit like that of a mocking bird, but both features are characteristic of the phoenix and her folkloric relatives. This image appears as a logo on the covers of the trilogy, and is clearly a phoenix in the sun.

For all the author's artistry, the contrast between Katniss' epic battles and the relatively mundane problems of growing up can occasionally seem a bit humorous. She can indeed become a mockingjay, a phoenix, but not at will or all the time. But, for her at least, maturity resides precisely in that lesson. She is at her best when she forgets the scripts prepared by others and simply does what she feels to be right. Perhaps, in the end, the role of mockingjay is really the epic dimension of normal life.

Traditional image of the feng huang or "Chinese phoenix" from an embroidery

Published on January 27, 2014 15:53

January 21, 2014

The Future of the Dog

Above photo: J. J. Grandville, "A Dog Walking His Man, 1868.

Perhaps because we still think of animals in terms of the iconic images of Aesop, the half-legendary Greek storyteller from the seventh-century BCE, there is a temptation to regard human relationships with animals as almost outside of time. We imagine the clever fox, the majestic lion, and the foolish donkey as though they were part of an eternal drama, but animals, and human relations with them, have changed enormously in the past century alone.

To appreciate the extent of these changes, consider the family dog. In around 1950, the family dog slept in its own "doghouse," but was expected to warn the family about intruders. Even in cities, pet dogs could run freely much of the time. Special foods for dogs were available, but they seemed frivolous to many people, and the family dog lived from scraps from the table. A dog would only get to see a veterinarian only when seriously ill. Professional dog training (known as "obedience school") was for the upper class, and most people found it a bit effete. Dogs could leave their feces in parks and almost nobody found that offensive. Strays were common, and there were lots of jokes about the dog-catchers' pursuit of them. Every now and then, dogs would even be eaten, usually not by Asian immigrants but by the poor. By contemporary standards, dogs were still half "wild."

Today, Western dogs share far more intimately in the life of human society, and are trained accordingly. They live in the family home and, outside of it, are hardly ever allowed off the leash, and must be accompanied by a person with a pooper-scooper. They have regular check-ups with a veterinarian, as well as a long list of shots, but many are born with respiratory difficulties, skeletal deformities, deafness, or other problems as a result of intensive breeding. Training is necessary and expected, since they are perpetually around men and women. Dogs in the West eat mostly foods that have been specially prepared for them; there are gourmet dog-foods, as well as lines of designer clothes for dogs. They also have prescription drugs, psychiatrists, jewelry, five-star hotels, hospices, and television shows. Just about every human practice and institution is being adapted for dogs, and they are usually not expected to provide any service beyond offering companionship.

Are the lives of dogs better or worse than in 1950? The old, pre-1950s world could be unsanitary and messy, but it had a greater sensual immediacy. It is hard to shake the feeling that the lives of dogs used to be more natural, though the concept of "nature" has itself become too elusive for many academics. An objective comparison is impossible.

But what does the future hold for dogs in the West? Perhaps, if the integration into human society continues, we could come to regard them as almost fully "human," with the rights and responsibilities that entails. Perhaps those canines that infringe on the regulations will be tried in special "dog courts," where they could be sentenced to prison time or even death. Will dogs be increasingly injected with human genetic material to a point where, over generations, they even begin to look like us? Alternatively, dogs and human beings may start to tire of one another's constant company. Perhaps, once again, there will be bands of feral dogs roaming the countryside, as there still are in much of Africa and Asia. I must leave such speculations to writers of science fiction.

But don't we human beings control our relations with animals? After all, we are the dominant species, right? In fact, we obviously don't even control our technologies. Nobody decides what devices shall be envisioned, invented, adopted, expanded, or discarded over the next few decades. We imagine all of humankind embodied in a single man or woman, who acts with a single will, and makes decisions accordingly. We may admire, love, curse, fight, hate, and reconcile with Humanity, but that great mother/father is actually not at home. There is really no such "Humanity," only five billion odd human beings, who, when they are lucky, get to make a few decisions about their own lives. Our changing relationships with animals, like technologies, are now very far beyond the ability of even the most conscientious scholars to follow, much less to predict or control.

J. J. Grandville, "A Dog Walking His Man, 1868.

Perhaps because we still think of animals in terms of the iconic images of Aesop, the half-legendary Greek storyteller from the seventh-century BCE, there is a temptation to regard human relationships with animals as almost outside of time. We imagine the clever fox, the majestic lion, and the foolish donkey as though they were part of an eternal drama, but animals, and human relations with them, have changed enormously in the past century alone.

To appreciate the extent of these changes, consider the family dog. In around 1950, the family dog slept in its own "doghouse," but was expected to warn the family about intruders. Even in cities, pet dogs could run freely much of the time. Special foods for dogs were available, but they seemed frivolous to many people, and the family dog lived from scraps from the table. A dog would only get to see a veterinarian only when seriously ill. Professional dog training (known as "obedience school") was for the upper class, and most people found it a bit effete. Dogs could leave their feces in parks and almost nobody found that offensive. Strays were common, and there were lots of jokes about the dog-catchers' pursuit of them. Every now and then, dogs would even be eaten, usually not by Asian immigrants but by the poor. By contemporary standards, dogs were still half "wild."

Today, Western dogs share far more intimately in the life of human society, and are trained accordingly. They live in the family home and, outside of it, are hardly ever allowed off the leash, and must be accompanied by a person with a pooper-scooper. They have regular check-ups with a veterinarian, as well as a long list of shots, but many are born with respiratory difficulties, skeletal deformities, deafness, or other problems as a result of intensive breeding. Training is necessary and expected, since they are perpetually around men and women. Dogs in the West eat mostly foods that have been specially prepared for them; there are gourmet dog-foods, as well as lines of designer clothes for dogs. They also have prescription drugs, psychiatrists, jewelry, five-star hotels, hospices, and television shows. Just about every human practice and institution is being adapted for dogs, and they are usually not expected to provide any service beyond offering companionship.

Are the lives of dogs better or worse than in 1950? The old, pre-1950s world could be unsanitary and messy, but it had a greater sensual immediacy. It is hard to shake the feeling that the lives of dogs used to be more natural, though the concept of "nature" has itself become too elusive for many academics. An objective comparison is impossible.

But what does the future hold for dogs in the West? Perhaps, if the integration into human society continues, we could come to regard them as almost fully "human," with the rights and responsibilities that entails. Perhaps those canines that infringe on the regulations will be tried in special "dog courts," where they could be sentenced to prison time or even death. Will dogs be increasingly injected with human genetic material to a point where, over generations, they even begin to look like us? Alternatively, dogs and human beings may start to tire of one another's constant company. Perhaps, once again, there will be bands of feral dogs roaming the countryside, as there still are in much of Africa and Asia. I must leave such speculations to writers of science fiction.

But don't we human beings control our relations with animals? After all, we are the dominant species, right? In fact, we obviously don't even control our technologies. Nobody decides what devices shall be envisioned, invented, adopted, expanded, or discarded over the next few decades. We imagine all of humankind embodied in a single man or woman, who acts with a single will, and makes decisions accordingly. We may admire, love, curse, fight, hate, and reconcile with Humanity, but that great mother/father is actually not at home. There is really no such "Humanity," only five billion odd human beings, who, when they are lucky, get to make a few decisions about their own lives. Our changing relationships with animals, like technologies, are now very far beyond the ability of even the most conscientious scholars to follow, much less to predict or control.

J. J. Grandville, "A Dog Walking His Man, 1868.

Published on January 21, 2014 15:28

January 8, 2014

Telling the Story of Humankind

Several myths of the origin of humankind have a touch of humor. The Pueblo Indians tell that Coyote once helped a great magician make people of clay, and bring them to life by baking them in a furnace. He left some undercooked, while others burned, and so most human beings are damaged to this day. Such tales seem to acknowledge that most of everyday life for human beings is defined by accidents rather than by some grand design.

The Biblical story of Adam and Eve, by contrast, has a stately majesty. The creation of the cosmos is a very purposeful, orderly affair, with a different task for each of six successive days. When Adam and Eve, at the instigation of the serpent, disobey a divine command, this is the first breakdown of the cosmic design. God is a gardener, and the first human beings are pests, a bit like whitetail deer nibbling at the flowers of a horticulturist today. Their expulsion is not so much a punishment as a practical step, designed to preserve divine harmony. Perhaps the defining theme of the story of humankind, as told in most of Western history, is homesickness for a lost paradise in which we lived in harmony with the natural world. But people viewed this loss ambivalently, often as a "fortunate fall," the first stage of emancipation from the violence and insecurity of the natural world, which might culminate in an existence as pure spirit.

Darwin's theory of evolution has provided another tale of human origins. As presented in most textbooks, at least until the late twentieth century, it retained most of the high drama of the Biblical account. Humankind became a bold fish, crawling out of the water, a bit like Columbus setting foot on the New World. The fins would gradually become arms, and the tail would become legs. It would learn to stand upright and, in time, rule the earth.

The triumphalist narrative made human beings so dominant that they ceased to be interesting. It was a sort of Horatio Alger story, in which a few twists of the plot might be novel but the basic progression and the ending were known in advance. Every new mutation, invention or cultural monument became a "step forward" for humanity. But the hero of this tale, however admirable s/he might seem, was not sufficiently vulnerable to inspire empathy. In addition, this narrative encouraged terrible feelings of guilt, confusion, and despair, for men and women could never live up to the expectations that it set.

Dissenters often retained the linear structure of this celebratory narrative, but made humanity the villain. Humankind, in other words, became a sort of Macbeth, stealing the throne of creation, and then murdering to retain it. There has always been a strong note of misanthropy running through Western culture. In Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1735), the hero visits an island where horses are clean and civilized but people are filthy. When his equine hostess proposes the extermination of humankind, he does not object, and this self-loathing of human beings may be a driving force in history. We have edged close to exterminating ourselves a few times, and might yet succeed.

As scientists learn ever more about human evolution, it ceases to be a story at all, since any grand themes and patterns are lost in an enormous mass of detail. Many people today have almost no sense of a collective past, and it is as though the world we know in the twenty-first century had just appeared from nowhere. On a perceptual level, the evolutionist and creationist paradigms are not as different as we may sometimes think.

To tell the story of humanity, we must now address the question of what it means to be human, not as a biological or even a philosophic query but as a poetic one. The tale of humankind should be a romance filled with drama, uncertainty, tragedy, and humor. Let us laugh at the foolishness of human arrogance, but let us also feel the pathos behind that human foolishness. Our "Dominance" is just a fiction that we made up in order to feel less afraid; ants and jellyfish appear destined to outlive us. If man is the protagonist of our story, let that figure be intriguing yet fallible, fragile yet tough, in other words, truly "human."

Hieronymus Bosch, The Creation of Adam and Eve (detail of "The Garden of Earthly Delights"), c. 1505

The Biblical story of Adam and Eve, by contrast, has a stately majesty. The creation of the cosmos is a very purposeful, orderly affair, with a different task for each of six successive days. When Adam and Eve, at the instigation of the serpent, disobey a divine command, this is the first breakdown of the cosmic design. God is a gardener, and the first human beings are pests, a bit like whitetail deer nibbling at the flowers of a horticulturist today. Their expulsion is not so much a punishment as a practical step, designed to preserve divine harmony. Perhaps the defining theme of the story of humankind, as told in most of Western history, is homesickness for a lost paradise in which we lived in harmony with the natural world. But people viewed this loss ambivalently, often as a "fortunate fall," the first stage of emancipation from the violence and insecurity of the natural world, which might culminate in an existence as pure spirit.

Darwin's theory of evolution has provided another tale of human origins. As presented in most textbooks, at least until the late twentieth century, it retained most of the high drama of the Biblical account. Humankind became a bold fish, crawling out of the water, a bit like Columbus setting foot on the New World. The fins would gradually become arms, and the tail would become legs. It would learn to stand upright and, in time, rule the earth.

The triumphalist narrative made human beings so dominant that they ceased to be interesting. It was a sort of Horatio Alger story, in which a few twists of the plot might be novel but the basic progression and the ending were known in advance. Every new mutation, invention or cultural monument became a "step forward" for humanity. But the hero of this tale, however admirable s/he might seem, was not sufficiently vulnerable to inspire empathy. In addition, this narrative encouraged terrible feelings of guilt, confusion, and despair, for men and women could never live up to the expectations that it set.

Dissenters often retained the linear structure of this celebratory narrative, but made humanity the villain. Humankind, in other words, became a sort of Macbeth, stealing the throne of creation, and then murdering to retain it. There has always been a strong note of misanthropy running through Western culture. In Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1735), the hero visits an island where horses are clean and civilized but people are filthy. When his equine hostess proposes the extermination of humankind, he does not object, and this self-loathing of human beings may be a driving force in history. We have edged close to exterminating ourselves a few times, and might yet succeed.

As scientists learn ever more about human evolution, it ceases to be a story at all, since any grand themes and patterns are lost in an enormous mass of detail. Many people today have almost no sense of a collective past, and it is as though the world we know in the twenty-first century had just appeared from nowhere. On a perceptual level, the evolutionist and creationist paradigms are not as different as we may sometimes think.

To tell the story of humanity, we must now address the question of what it means to be human, not as a biological or even a philosophic query but as a poetic one. The tale of humankind should be a romance filled with drama, uncertainty, tragedy, and humor. Let us laugh at the foolishness of human arrogance, but let us also feel the pathos behind that human foolishness. Our "Dominance" is just a fiction that we made up in order to feel less afraid; ants and jellyfish appear destined to outlive us. If man is the protagonist of our story, let that figure be intriguing yet fallible, fragile yet tough, in other words, truly "human."

Hieronymus Bosch, The Creation of Adam and Eve (detail of "The Garden of Earthly Delights"), c. 1505

Published on January 08, 2014 16:31

Told Me by a Butterfly

We writers constantly try to build up our own confidence by getting published, making sales, winning prizes, joining cliques or proclaiming theories. The passion to write constantly strips this vanity

We writers constantly try to build up our own confidence by getting published, making sales, winning prizes, joining cliques or proclaiming theories. The passion to write constantly strips this vanity aside and forces us to confront that loneliness and the uncertainty with which human beings, in the end, live and die. I cannot reveal my love, without exposing my vanities, and that is the fate of writers.

...more

- Boria Sax's profile

- 76 followers