Boria Sax's Blog: Told Me by a Butterfly, page 4

August 7, 2015

A Plague of Locusts

The transformation of grasshoppers to locusts is eerily reminiscent of ways that human beings can at times change as population density increases.

Published on August 07, 2015 10:40

June 12, 2015

Why the French Army Collapsed at Waterloo

After the two sides had been nearly equal for most of the day at the Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon ordered his elite Imperial Guard to charge, and, shortly afterward, the French front abruptly collapsed, with a completeness that was unprecedented on any side in the Napoleonic Wars and perhaps in the preceding centuries. According to several witnesses, cries of "Sauve qui peut!" ("Save yourself who can.") went through the French army. For those who believed that some sort of Providence was revealed through history, the dramatic end seemed to signal a turning point, whether it offered a prosperous future or tragic grandeur. The 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo is to be commemorated on June 18th. The remembrances are mostly a matter of nostalgia, focusing on pageantry, uniforms, ceremony, and theater, as well as on small details of the conflict. We are so far from the period that today just about everyone can find something to be wistful about.

There will be a reenactment of the battle, perhaps more elaborate than any such display before, but we should not let a magnificent spectacle distract us from asking probing questions. Why did the French front disintegrate in such an unparalleled way? The charge of the Imperial Guard was clearly a fiasco, but there have been plenty of other disastrous assaults in history, such as Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg in the American Civil War or the English Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava in the Crimean War. Neither of those was followed by a breakdown of dsicipline similar to that of the French at Waterloo. The explanation must be, at least in part, because, after over a decade and a half of fighting for abstractions such as "glory" (which seemed increasingly hollow amid repeated scenes of carnage), the soldiers were bone-weary.

Not since the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) had a Continental army battled continuously for so long a time, and soldiers of the early seventeenth century were notorious for flouting the wishes of their officers. Napoleon's men had fought two intense yet indecisive battles on the previous day, and broke down under the accumulation of psychological and physical stress. Historians have at times claimed that an army of seasoned veterans was an advantage for Napoleon at the start of the Battle of Waterloo, but it may have been a fatal handicap instead. Many, including commanders such as Marshal Ney and even Napoleon himself, were probably far more traumatized, and more erratic, than anybody realized at the time. A warning precedent, albeit an ironic one, was how the army had deserted Louis XVIII for Napoleon a few months before. They were, to put it bluntly, sick and tired of the very things that people are commemorating now.

But the victors at Waterloo, Wellington very much included, had good reason to retain a legend of Napoleon, since the presence of a formidable adversary added to their achievement. A knight errant, after all, requires a dragon to slay. As a result, the reality of the battle was concealed by propaganda from both parties. People can become nostalgic about anything, including the eras of brutal conflicts, plagues, natural catastrophes, and ruthless dictatorships. They need only remember very selectively and then find, or else imagine, some redeeming quality such as solidarity or the opportunity for heroism. War, especially, blends experience and fantasy in the most seductive way, by means of decorations, costumes, songs, rituals, and colorful tales. When wars are in progress, people wish fervently for them to end, but, when they are over, people look back at them with a paradoxical affection. There cannot be much harm in wishing the days of Waterloo were back, since that can never come about, but we should try not to lose perspective. Let us, then, indulge ourselves by "remembering" Waterloo for a week, but then then forget it in the years to come.

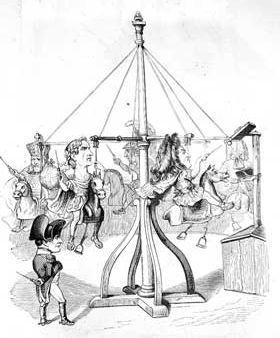

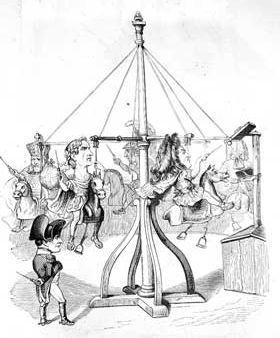

Cartoon by J. J. Grandville, 1844. Generals of the past are shown as little boys taking rides at an amusement park. Alexander, Caesar, Charlemange, Louis XIV, and Marshal de Saxe have their turns, while Napoleon impatiently waits for his.

There will be a reenactment of the battle, perhaps more elaborate than any such display before, but we should not let a magnificent spectacle distract us from asking probing questions. Why did the French front disintegrate in such an unparalleled way? The charge of the Imperial Guard was clearly a fiasco, but there have been plenty of other disastrous assaults in history, such as Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg in the American Civil War or the English Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava in the Crimean War. Neither of those was followed by a breakdown of dsicipline similar to that of the French at Waterloo. The explanation must be, at least in part, because, after over a decade and a half of fighting for abstractions such as "glory" (which seemed increasingly hollow amid repeated scenes of carnage), the soldiers were bone-weary.

Not since the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) had a Continental army battled continuously for so long a time, and soldiers of the early seventeenth century were notorious for flouting the wishes of their officers. Napoleon's men had fought two intense yet indecisive battles on the previous day, and broke down under the accumulation of psychological and physical stress. Historians have at times claimed that an army of seasoned veterans was an advantage for Napoleon at the start of the Battle of Waterloo, but it may have been a fatal handicap instead. Many, including commanders such as Marshal Ney and even Napoleon himself, were probably far more traumatized, and more erratic, than anybody realized at the time. A warning precedent, albeit an ironic one, was how the army had deserted Louis XVIII for Napoleon a few months before. They were, to put it bluntly, sick and tired of the very things that people are commemorating now.

But the victors at Waterloo, Wellington very much included, had good reason to retain a legend of Napoleon, since the presence of a formidable adversary added to their achievement. A knight errant, after all, requires a dragon to slay. As a result, the reality of the battle was concealed by propaganda from both parties. People can become nostalgic about anything, including the eras of brutal conflicts, plagues, natural catastrophes, and ruthless dictatorships. They need only remember very selectively and then find, or else imagine, some redeeming quality such as solidarity or the opportunity for heroism. War, especially, blends experience and fantasy in the most seductive way, by means of decorations, costumes, songs, rituals, and colorful tales. When wars are in progress, people wish fervently for them to end, but, when they are over, people look back at them with a paradoxical affection. There cannot be much harm in wishing the days of Waterloo were back, since that can never come about, but we should try not to lose perspective. Let us, then, indulge ourselves by "remembering" Waterloo for a week, but then then forget it in the years to come.

Cartoon by J. J. Grandville, 1844. Generals of the past are shown as little boys taking rides at an amusement park. Alexander, Caesar, Charlemange, Louis XIV, and Marshal de Saxe have their turns, while Napoleon impatiently waits for his.

Published on June 12, 2015 08:14

Why the French Army Collapsed at Waterloo

Not since the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) had a Continental army battled continuously for so long a time, and soldiers of the early seventeenth century were notorious for flouting the wishes of their officers.

Published on June 12, 2015 07:16

May 26, 2015

What is it like to be an Octopus?

To imagine yourself an octopus, you must perhaps divide your very consciousness into at least seven parts, six arms or more and a head. To imagine this, you might think of seven friends or brothers, so close that they seem to be "inseparable."

Published on May 26, 2015 11:43

May 12, 2015

Coming to Terms With the Past, as a Citizen, a Writer and a Human Being

"Vergangenheitsbewἄltigung" literally means "overpowering the past," and that is a thing that we can never do. Why even bother to come to terms with it? Why not simply forget the past, as, indeed, many people today appear to have done?

Published on May 12, 2015 09:13

Coming to Terms With the Past, as a Citizen, a Writer and a Human Being

"Vergangenheitsbew���ltigung" is a coinage in German that is used to mean something like "coming to terms with the past." That is the major theme of post-World War II German literature, but, considering the effort that was expended, leading literary figures have done a remarkably poor job of it. It was an obsession of Christa Wolf, an author in former East Germany who critics long considered a major candidate for the Nobel Prize, as well as of the late G���nter Grass, who won the Nobel Prize in 1999. Wolf managed to block from her mind the fact that she had worked as an informant for the Stasi, the East German secret police, until that was revealed by archives in 1993. For most of his career, Grass hid the fact that he had been a member of the notorious Waffen SS, before finally revealing it in his 2007 memoir

Peeling the Onion

.

One explanation of these failures is offered by their fellow German W. G. Sebald, a major candidate for the Nobel Prize before his premature death in 2001, in On the Natural History of Destruction (1999). Even as they acknowledged the Nazi crimes, these German authors had repressed awareness of the suffering that they had witnessed among their own people, when cities were bombed to rubble, people starved, and, at the end of the war, an additional 2.1 million were killed as the governments of Poland and Czechoslovakia forcibly evicted ethnic Germans from their ancestral homes. Sebald writes, "The almost entire absence of profound disturbance to the inner life of the nation suggests that the new Federal German society relegated the experiences of its own prehistory to the back of its mind and developed an almost perfectly functioning mechanism of repression..." This does not imply that there was an equivalence between the crimes by and those against the Germans. The obligation of a writer, however, is to confront his own experience, and the Germans could not do justice to that while hiding so much trauma from themselves.

Every country, ethnicity, or major subculture has matters that it does not care to acknowledge. The Japanese do not always admit to the sexual abuse of the Korean "comfort women" during World War II, and the Turks regularly deny the genocide of Armenians at the start of World War I. In the United States we have, of course, the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement of Blacks, in addition to many other crimes against humanity that only appear "minor" by comparison.

I remain a fairly unregenerate man of the left. In the United States and throughout the world, the left has lost a lot of credibility by its past support of figures such as Stalin, Mao, and Kim Il Sung. As at least a charter member of that community, I feel a special obligation to help redress that failing. In many cases at least, I believe the offense was usually due less to malice than to very human errors of judgement, but that is no excuse for ignoring or trivializing it now. We need to ask why so many of us allowed themselves to be hypnotized by an ideology, to the extent that they failed to perceive some of the most egregious human rights violations ever.

But, assuming Sebald is correct, there are things about this German pattern of psychological repression that seem paradoxical. Other countries such as Russia, Ireland, Serbia, and Israel are perpetually commemorating their own suffering yet have trouble acknowledging guilt, the reverse of what Sebald finds in Germany. For Germans, furthermore, Vergangenheitsbew���ltigung is a matter of values and philosophy, but for Americans it is mostly one of business and politics. In contrast to the Germans, we have engaged in little soul-searching or philosophizing about national crimes. Traditions going back to the first European settlement made America, the "New Eden," the place where humanity might cast off its past, so full of wars and intrigues, and make a fresh start. On some level, we still believe in a primal innocence that might relatively easily be recaptured through a change of heart, if we could only find the right policy.

Every country, and probably every culture, has its own way of selectively remembering, and forgetting, the past, and perhaps that contributes as much to its identity as the past itself. That is why the national state emerged as a major ideal in the latter nineteenth century, at about the same time as history became a distinct academic discipline. This national style involves selecting a few themes and previous events, which may underscore victory, defeat, empire-building, victimization, triumph, guilt, prosperity, hardship or many other things. These are then taken at least partly out of context and romanticized, often in intellectually highly sophisticated ways.

That is a sort of mythologizing that generally has remarkably little difficulty accommodating internal contradictions. In the United States, we honor the heroism of both the South, fighting for autonomy, and the North, fighting to end slavery, in the Civil War. In some states such as Arkansas and Mississippi, Martin Luther King Jr., the crusader for Black rights, shares a holiday with Robert E. Lee, commander of the rebellion that opposed Black rights. In a similar way, Russians now often honor adversaries Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Stalin, and President Vladimir Putin may see himself as the successor to both. The Arc de Triomphe was originally conceived by Napoleon to memorialize his victory in Egypt, which quickly turned into the first in a series of catastrophic defeats. The arch was completed by subsequent regimes, making it simultaneously a celebration of Napoleon, of the French Revolution that he ended, and of the Bourbon Kings who replaced him, along with King Louis-Phillippe who replaced the Bourbons. Elaborate rationalizations are always essential to national or ethnic identity.

But the incoherence of virtually all national mythologies begins to become apparent when they are juxtaposed in ways that force their inherent contradictions to the surface. We see this is the decision of Western leaders to boycott the military parade in Moscow on May 9, 2015, to mark the end of World War II. Their absence reflects a displeasure over Russian support for the rebels in Ukraine, but that, in turn, is intimately tied to differing perspectives on events of World War II, as well as on many that led up to and followed the war. Britain held out against the Nazis almost alone for over a year, and the Americans commanded the Allied forces at D-Day, but it was the Russians who did most of the fighting, losing 20 to 30 million people. Ukrainians remember the Holodomor, the 1922 famine in Ukraine, caused or at least actively encouraged by Stalin, which killed, by some estimates, up to seven million people or more. The Russians remember the widespread support for the Nazis in Ukraine, where many people initially greeted them as liberators. As is so often the case, it is just about impossible to untangle the mix of history, mythology, and politics, among all the countries involved.

"Vergangenheitsbew���ltigung" literally means "overpowering the past," and that is a thing that we can never do. Why even bother to come to terms with it? Why not simply forget the past, as, indeed, many people today appear to have done? Our link with the past is, in any case, tenuous as best. Edward Gibbon, in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, called history "little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind." Nevertheless, Gibbon devoted his life to recording it. We are easily overwhelmed by the vastness, the brutality, and complexity of the historical record. History contains no clear lessons, and no promise of redemption. I love it anyhow. History, for better or worse, is "us" on a grand scale ��� full of secrets, beauty, fear, longing, and stifled love. Without history, our lives would not be complete, and we could not be, in the best sense, fully "human."

French Cartoon, 1815. The caption reads, "'If the plague paid the pensions, the plague would also have flatterers and courtiers.' Saahdi." The man, responding to each trend like a weather vane, signs allegiance to the a series of governments that have come to power in the last two and a half decades.

One explanation of these failures is offered by their fellow German W. G. Sebald, a major candidate for the Nobel Prize before his premature death in 2001, in On the Natural History of Destruction (1999). Even as they acknowledged the Nazi crimes, these German authors had repressed awareness of the suffering that they had witnessed among their own people, when cities were bombed to rubble, people starved, and, at the end of the war, an additional 2.1 million were killed as the governments of Poland and Czechoslovakia forcibly evicted ethnic Germans from their ancestral homes. Sebald writes, "The almost entire absence of profound disturbance to the inner life of the nation suggests that the new Federal German society relegated the experiences of its own prehistory to the back of its mind and developed an almost perfectly functioning mechanism of repression..." This does not imply that there was an equivalence between the crimes by and those against the Germans. The obligation of a writer, however, is to confront his own experience, and the Germans could not do justice to that while hiding so much trauma from themselves.

Every country, ethnicity, or major subculture has matters that it does not care to acknowledge. The Japanese do not always admit to the sexual abuse of the Korean "comfort women" during World War II, and the Turks regularly deny the genocide of Armenians at the start of World War I. In the United States we have, of course, the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement of Blacks, in addition to many other crimes against humanity that only appear "minor" by comparison.

I remain a fairly unregenerate man of the left. In the United States and throughout the world, the left has lost a lot of credibility by its past support of figures such as Stalin, Mao, and Kim Il Sung. As at least a charter member of that community, I feel a special obligation to help redress that failing. In many cases at least, I believe the offense was usually due less to malice than to very human errors of judgement, but that is no excuse for ignoring or trivializing it now. We need to ask why so many of us allowed themselves to be hypnotized by an ideology, to the extent that they failed to perceive some of the most egregious human rights violations ever.

But, assuming Sebald is correct, there are things about this German pattern of psychological repression that seem paradoxical. Other countries such as Russia, Ireland, Serbia, and Israel are perpetually commemorating their own suffering yet have trouble acknowledging guilt, the reverse of what Sebald finds in Germany. For Germans, furthermore, Vergangenheitsbew���ltigung is a matter of values and philosophy, but for Americans it is mostly one of business and politics. In contrast to the Germans, we have engaged in little soul-searching or philosophizing about national crimes. Traditions going back to the first European settlement made America, the "New Eden," the place where humanity might cast off its past, so full of wars and intrigues, and make a fresh start. On some level, we still believe in a primal innocence that might relatively easily be recaptured through a change of heart, if we could only find the right policy.

Every country, and probably every culture, has its own way of selectively remembering, and forgetting, the past, and perhaps that contributes as much to its identity as the past itself. That is why the national state emerged as a major ideal in the latter nineteenth century, at about the same time as history became a distinct academic discipline. This national style involves selecting a few themes and previous events, which may underscore victory, defeat, empire-building, victimization, triumph, guilt, prosperity, hardship or many other things. These are then taken at least partly out of context and romanticized, often in intellectually highly sophisticated ways.

That is a sort of mythologizing that generally has remarkably little difficulty accommodating internal contradictions. In the United States, we honor the heroism of both the South, fighting for autonomy, and the North, fighting to end slavery, in the Civil War. In some states such as Arkansas and Mississippi, Martin Luther King Jr., the crusader for Black rights, shares a holiday with Robert E. Lee, commander of the rebellion that opposed Black rights. In a similar way, Russians now often honor adversaries Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Stalin, and President Vladimir Putin may see himself as the successor to both. The Arc de Triomphe was originally conceived by Napoleon to memorialize his victory in Egypt, which quickly turned into the first in a series of catastrophic defeats. The arch was completed by subsequent regimes, making it simultaneously a celebration of Napoleon, of the French Revolution that he ended, and of the Bourbon Kings who replaced him, along with King Louis-Phillippe who replaced the Bourbons. Elaborate rationalizations are always essential to national or ethnic identity.

But the incoherence of virtually all national mythologies begins to become apparent when they are juxtaposed in ways that force their inherent contradictions to the surface. We see this is the decision of Western leaders to boycott the military parade in Moscow on May 9, 2015, to mark the end of World War II. Their absence reflects a displeasure over Russian support for the rebels in Ukraine, but that, in turn, is intimately tied to differing perspectives on events of World War II, as well as on many that led up to and followed the war. Britain held out against the Nazis almost alone for over a year, and the Americans commanded the Allied forces at D-Day, but it was the Russians who did most of the fighting, losing 20 to 30 million people. Ukrainians remember the Holodomor, the 1922 famine in Ukraine, caused or at least actively encouraged by Stalin, which killed, by some estimates, up to seven million people or more. The Russians remember the widespread support for the Nazis in Ukraine, where many people initially greeted them as liberators. As is so often the case, it is just about impossible to untangle the mix of history, mythology, and politics, among all the countries involved.

"Vergangenheitsbew���ltigung" literally means "overpowering the past," and that is a thing that we can never do. Why even bother to come to terms with it? Why not simply forget the past, as, indeed, many people today appear to have done? Our link with the past is, in any case, tenuous as best. Edward Gibbon, in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, called history "little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind." Nevertheless, Gibbon devoted his life to recording it. We are easily overwhelmed by the vastness, the brutality, and complexity of the historical record. History contains no clear lessons, and no promise of redemption. I love it anyhow. History, for better or worse, is "us" on a grand scale ��� full of secrets, beauty, fear, longing, and stifled love. Without history, our lives would not be complete, and we could not be, in the best sense, fully "human."

French Cartoon, 1815. The caption reads, "'If the plague paid the pensions, the plague would also have flatterers and courtiers.' Saahdi." The man, responding to each trend like a weather vane, signs allegiance to the a series of governments that have come to power in the last two and a half decades.

Published on May 12, 2015 07:13

April 21, 2015

History and Experience: Revisiting My Childhood in a File from the FBI

When experience has been ordered, processed, edited, and cataloged, we call it "history." That bears about the same relation to the chaos of events in progress as a stack of boards and a bag of leaves does to a wind-battered tree in August.

Published on April 21, 2015 07:27

February 25, 2015

The Islamic State, The M��nster Rebellion, And the Apocalypse

History contains no simple lessons, but it is filled with suggestive comparisons and analogies. It does not enable anybody to predict the future, but it does help us develop a sort of intuition, a form of worldly wisdom. Through the study of history, one learns, for example, to recognize hubris in a ruler, at times when almost everyone else is carried away by his glamour. When Talleyrand learned of Napoleon's plan to invade Russia, he knew that the Emperor was doomed.

More complex patterns occasionally emerge in widely separated eras, and I think there are some very strong analogies between the Islamic State today and the German city of Münster, when it was seized by Anabaptists in the year 1534. Forces allied with the mighty Holy Roman Empire assembled a large army and laid siege to Münster. As the plight of its citizens became ever more desperate, a young man who called himself "Jan van Leyden" took control, and his rule grew increasingly capricious and violent. Previously, Jan had been an apprentice tailor, an aspiring actor, and an unsuccessful innkeeper, but, claiming the will of God had been revealed to him in visions, he had himself declared king. While others in his city starved, and were even reduced to cannibalism, Jan and his close associates lived in royal splendor, all, he claimed, for the glory of God. Jan told his followers that Münster was the New Jerusalem, and that he, Jan, was the new David. In imitation of the Biblical patriarchs, he instituted polygamy, igniting a rebellion that almost toppled him, before it was bloodily put down. He took sixteen women for himself, and when one of them, Elizabeth Wandsherer, rebelled against him, he personally beheaded her in the marketplace, and then danced gaily around her body with his other wives.

"Jan van Leiden" by Heinrich Aldegrever, 1536

The Anabaptists were radical Protestants, who went beyond Martin Luther by questioning not only ecclesiastical but also worldly power. They rejected infant baptism, formal clergy, secular hierarchies, and private property. The only authority they accepted was that of either the Bible or of direct revelations from God. How could Jan establish absolute power in the name of an ideology that was, in so many ways, anti-authoritarian? In the sixteenth century, many people of all persuasions believed that the political, intellectual, and religious turbulence of their time presaged the imminent end of the world. Prophetic visions were common, and King Jan was only one of several Anabaptists who laid claim to them. So did many Catholics including Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, while Martin Luther once threw an inkwell at the Devil. It was a time in which extremes of skepticism and religious fervor thrived, often alongside one another. King Jan was a flamboyant showman who ruled not only by terror, but also by involving his subjects in the ongoing drama of his guilt, repentance, melancholy, and divine election. He, at times, went into moody seclusion, to emerge with a rejuvenated sense of mission, and danced naked in the marketplace to show his innocence before God.

Just as the Anabaptists tried to recreate the kingdom of ancient Israel, the Islamic State now endeavors to reestablish the caliphate of the seventh century. The followers of King Jan believed they were living in the last days of the world, as do those of the Islamic State today. Both practice extreme violence, absolute subjugation of women, desecrating the sacred symbols of other faiths, and flaunting of their transgressions. Finally, both the Münster Anabaptists and advocates of the Islamic State have often startled observers with their theological sophistication. They have been difficult for more conventional religious leaders to deal with, because they simply take commonly held ideas to extremes.

More generally, the crisis of Islam today, as it fragments into antagonistic factions, bears some resemblance to that of Christianity in the sixteenth century. Yet even detailed historical patterns can be like faces that we see in clouds, landscapes that we see in agate, or prophesies of the Delphic oracle. It is not easy to be sure whether they should be attributed to similar dynamics, providence, or our active imaginations. Caution is in order, but the history of the Anabaptist kingdom may provide some hints about both the possible nature and the eventual fate of the Islamic State.

After holding out for 18 months, the Anabaptists in Münster were finally forced to surrender. King Jan was initially defiant, but he eventually repented his claim to royalty, and accepted the ministrations of a Catholic priest on the night before he was finally tortured to death. Perhaps he was basically a young man who, disoriented by the carnage he had already experienced, was overpowered by adolescent daydreams. Among those Anabaptists who survived, a few, known as the "Batenburgers," for a while continued their practices of extreme violence and polygamy. The larger number firmly renounced both, and their spiritual descendants today include the Mennonites and Amish, who are among the most pacifistic peoples in the world. Opposition to the Anabaptists in Münster brought together warring Catholics and Protestants, thus beginning a movement for religious tolerance. Like that of the rebels in Münster, the ultimate legacy of ISIS may be providing almost everyone with a model of something they do not wish to become.

More complex patterns occasionally emerge in widely separated eras, and I think there are some very strong analogies between the Islamic State today and the German city of Münster, when it was seized by Anabaptists in the year 1534. Forces allied with the mighty Holy Roman Empire assembled a large army and laid siege to Münster. As the plight of its citizens became ever more desperate, a young man who called himself "Jan van Leyden" took control, and his rule grew increasingly capricious and violent. Previously, Jan had been an apprentice tailor, an aspiring actor, and an unsuccessful innkeeper, but, claiming the will of God had been revealed to him in visions, he had himself declared king. While others in his city starved, and were even reduced to cannibalism, Jan and his close associates lived in royal splendor, all, he claimed, for the glory of God. Jan told his followers that Münster was the New Jerusalem, and that he, Jan, was the new David. In imitation of the Biblical patriarchs, he instituted polygamy, igniting a rebellion that almost toppled him, before it was bloodily put down. He took sixteen women for himself, and when one of them, Elizabeth Wandsherer, rebelled against him, he personally beheaded her in the marketplace, and then danced gaily around her body with his other wives.

"Jan van Leiden" by Heinrich Aldegrever, 1536

The Anabaptists were radical Protestants, who went beyond Martin Luther by questioning not only ecclesiastical but also worldly power. They rejected infant baptism, formal clergy, secular hierarchies, and private property. The only authority they accepted was that of either the Bible or of direct revelations from God. How could Jan establish absolute power in the name of an ideology that was, in so many ways, anti-authoritarian? In the sixteenth century, many people of all persuasions believed that the political, intellectual, and religious turbulence of their time presaged the imminent end of the world. Prophetic visions were common, and King Jan was only one of several Anabaptists who laid claim to them. So did many Catholics including Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, while Martin Luther once threw an inkwell at the Devil. It was a time in which extremes of skepticism and religious fervor thrived, often alongside one another. King Jan was a flamboyant showman who ruled not only by terror, but also by involving his subjects in the ongoing drama of his guilt, repentance, melancholy, and divine election. He, at times, went into moody seclusion, to emerge with a rejuvenated sense of mission, and danced naked in the marketplace to show his innocence before God.

Just as the Anabaptists tried to recreate the kingdom of ancient Israel, the Islamic State now endeavors to reestablish the caliphate of the seventh century. The followers of King Jan believed they were living in the last days of the world, as do those of the Islamic State today. Both practice extreme violence, absolute subjugation of women, desecrating the sacred symbols of other faiths, and flaunting of their transgressions. Finally, both the Münster Anabaptists and advocates of the Islamic State have often startled observers with their theological sophistication. They have been difficult for more conventional religious leaders to deal with, because they simply take commonly held ideas to extremes.

More generally, the crisis of Islam today, as it fragments into antagonistic factions, bears some resemblance to that of Christianity in the sixteenth century. Yet even detailed historical patterns can be like faces that we see in clouds, landscapes that we see in agate, or prophesies of the Delphic oracle. It is not easy to be sure whether they should be attributed to similar dynamics, providence, or our active imaginations. Caution is in order, but the history of the Anabaptist kingdom may provide some hints about both the possible nature and the eventual fate of the Islamic State.

After holding out for 18 months, the Anabaptists in Münster were finally forced to surrender. King Jan was initially defiant, but he eventually repented his claim to royalty, and accepted the ministrations of a Catholic priest on the night before he was finally tortured to death. Perhaps he was basically a young man who, disoriented by the carnage he had already experienced, was overpowered by adolescent daydreams. Among those Anabaptists who survived, a few, known as the "Batenburgers," for a while continued their practices of extreme violence and polygamy. The larger number firmly renounced both, and their spiritual descendants today include the Mennonites and Amish, who are among the most pacifistic peoples in the world. Opposition to the Anabaptists in Münster brought together warring Catholics and Protestants, thus beginning a movement for religious tolerance. Like that of the rebels in Münster, the ultimate legacy of ISIS may be providing almost everyone with a model of something they do not wish to become.

Published on February 25, 2015 10:14

The Islamic State, The Münster Rebellion, And the Apocalypse

History contains no simple lessons, but it is filled with suggestive comparisons and analogies. It does not enable anybody to predict the future, but it does help us develop a sort of intuition, a form of worldly wisdom. Through the study of history, one learns, for example, to recognize hubris in a ruler, at times when almost everyone else is carried away by his glamour. When Talleyrand learned of Napoleon's plan to invade Russia, he knew that the Emperor was doomed.

More complex patterns occasionally emerge in widely separated eras, and I think there are some very strong analogies between the Islamic State today and the German city of Münster, when it was seized by Anabaptists in the year 1534. Forces allied with the mighty Holy Roman Empire assembled a large army and laid siege to Münster. As the plight of its citizens became ever more desperate, a young man who called himself "Jan van Leyden" took control, and his rule grew increasingly capricious and violent. Previously, Jan had been an apprentice tailor, an aspiring actor, and an unsuccessful innkeeper, but, claiming the will of God had been revealed to him in visions, he had himself declared king. While others in his city starved, and were even reduced to cannibalism, Jan and his close associates lived in royal splendor, all, he claimed, for the glory of God. Jan told his followers that Münster was the New Jerusalem, and that he, Jan, was the new David. In imitation of the Biblical patriarchs, he instituted polygamy, igniting a rebellion that almost toppled him, before it was bloodily put down. He took sixteen women for himself, and when one of them, Elizabeth Wandsherer, rebelled against him, he personally beheaded her in the marketplace, and then danced gaily around her body with his other wives.

"Jan van Leiden" by Heinrich Aldegrever, 1536

The Anabaptists were radical Protestants, who went beyond Martin Luther by questioning not only ecclesiastical but also worldly power. They rejected infant baptism, formal clergy, secular hierarchies, and private property. The only authority they accepted was that of either the Bible or of direct revelations from God. How could Jan establish absolute power in the name of an ideology that was, in so many ways, anti-authoritarian? In the sixteenth century, many people of all persuasions believed that the political, intellectual, and religious turbulence of their time presaged the imminent end of the world. Prophetic visions were common, and King Jan was only one of several Anabaptists who laid claim to them. So did many Catholics including Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, while Martin Luther once threw an inkwell at the Devil. It was a time in which extremes of skepticism and religious fervor thrived, often alongside one another. King Jan was a flamboyant showman who ruled not only by terror, but also by involving his subjects in the ongoing drama of his guilt, repentance, melancholy, and divine election. He, at times, went into moody seclusion, to emerge with a rejuvenated sense of mission, and danced naked in the marketplace to show his innocence before God.

Just as the Anabaptists tried to recreate the kingdom of ancient Israel, the Islamic State now endeavors to reestablish the caliphate of the seventh century. The followers of King Jan believed they were living in the last days of the world, as do those of the Islamic State today. Both practice extreme violence, absolute subjugation of women, desecrating the sacred symbols of other faiths, and flaunting of their transgressions. Finally, both the Münster Anabaptists and advocates of the Islamic State have often startled observers with their theological sophistication. They have been difficult for more conventional religious leaders to deal with, because they simply take commonly held ideas to extremes.

More generally, the crisis of Islam today, as it fragments into antagonistic factions, bears some resemblance to that of Christianity in the sixteenth century. Yet even detailed historical patterns can be like faces that we see in clouds, landscapes that we see in agate, or prophesies of the Delphic oracle. It is not easy to be sure whether they should be attributed to similar dynamics, providence, or our active imaginations. Caution is in order, but the history of the Anabaptist kingdom may provide some hints about both the possible nature and the eventual fate of the Islamic State.

After holding out for 18 months, the Anabaptists in Münster were finally forced to surrender. King Jan was initially defiant, but he eventually repented his claim to royalty, and accepted the ministrations of a Catholic priest on the night before he was finally tortured to death. Perhaps he was basically a young man who, disoriented by the carnage he had already experienced, was overpowered by adolescent daydreams. Among those Anabaptists who survived, a few, known as the "Batenburgers," for a while continued their practices of extreme violence and polygamy. The larger number firmly renounced both, and their spiritual descendants today include the Mennonites and Amish, who are among the most pacifistic peoples in the world. Opposition to the Anabaptists in Münster brought together warring Catholics and Protestants, thus beginning a movement for religious tolerance. Like that of the rebels in Münster, the ultimate legacy of ISIS may be providing almost everyone with a model of something they do not wish to become.

More complex patterns occasionally emerge in widely separated eras, and I think there are some very strong analogies between the Islamic State today and the German city of Münster, when it was seized by Anabaptists in the year 1534. Forces allied with the mighty Holy Roman Empire assembled a large army and laid siege to Münster. As the plight of its citizens became ever more desperate, a young man who called himself "Jan van Leyden" took control, and his rule grew increasingly capricious and violent. Previously, Jan had been an apprentice tailor, an aspiring actor, and an unsuccessful innkeeper, but, claiming the will of God had been revealed to him in visions, he had himself declared king. While others in his city starved, and were even reduced to cannibalism, Jan and his close associates lived in royal splendor, all, he claimed, for the glory of God. Jan told his followers that Münster was the New Jerusalem, and that he, Jan, was the new David. In imitation of the Biblical patriarchs, he instituted polygamy, igniting a rebellion that almost toppled him, before it was bloodily put down. He took sixteen women for himself, and when one of them, Elizabeth Wandsherer, rebelled against him, he personally beheaded her in the marketplace, and then danced gaily around her body with his other wives.

"Jan van Leiden" by Heinrich Aldegrever, 1536

The Anabaptists were radical Protestants, who went beyond Martin Luther by questioning not only ecclesiastical but also worldly power. They rejected infant baptism, formal clergy, secular hierarchies, and private property. The only authority they accepted was that of either the Bible or of direct revelations from God. How could Jan establish absolute power in the name of an ideology that was, in so many ways, anti-authoritarian? In the sixteenth century, many people of all persuasions believed that the political, intellectual, and religious turbulence of their time presaged the imminent end of the world. Prophetic visions were common, and King Jan was only one of several Anabaptists who laid claim to them. So did many Catholics including Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, while Martin Luther once threw an inkwell at the Devil. It was a time in which extremes of skepticism and religious fervor thrived, often alongside one another. King Jan was a flamboyant showman who ruled not only by terror, but also by involving his subjects in the ongoing drama of his guilt, repentance, melancholy, and divine election. He, at times, went into moody seclusion, to emerge with a rejuvenated sense of mission, and danced naked in the marketplace to show his innocence before God.

Just as the Anabaptists tried to recreate the kingdom of ancient Israel, the Islamic State now endeavors to reestablish the caliphate of the seventh century. The followers of King Jan believed they were living in the last days of the world, as do those of the Islamic State today. Both practice extreme violence, absolute subjugation of women, desecrating the sacred symbols of other faiths, and flaunting of their transgressions. Finally, both the Münster Anabaptists and advocates of the Islamic State have often startled observers with their theological sophistication. They have been difficult for more conventional religious leaders to deal with, because they simply take commonly held ideas to extremes.

More generally, the crisis of Islam today, as it fragments into antagonistic factions, bears some resemblance to that of Christianity in the sixteenth century. Yet even detailed historical patterns can be like faces that we see in clouds, landscapes that we see in agate, or prophesies of the Delphic oracle. It is not easy to be sure whether they should be attributed to similar dynamics, providence, or our active imaginations. Caution is in order, but the history of the Anabaptist kingdom may provide some hints about both the possible nature and the eventual fate of the Islamic State.

After holding out for 18 months, the Anabaptists in Münster were finally forced to surrender. King Jan was initially defiant, but he eventually repented his claim to royalty, and accepted the ministrations of a Catholic priest on the night before he was finally tortured to death. Perhaps he was basically a young man who, disoriented by the carnage he had already experienced, was overpowered by adolescent daydreams. Among those Anabaptists who survived, a few, known as the "Batenburgers," for a while continued their practices of extreme violence and polygamy. The larger number firmly renounced both, and their spiritual descendants today include the Mennonites and Amish, who are among the most pacifistic peoples in the world. Opposition to the Anabaptists in Münster brought together warring Catholics and Protestants, thus beginning a movement for religious tolerance. Like that of the rebels in Münster, the ultimate legacy of ISIS may be providing almost everyone with a model of something they do not wish to become.

Published on February 25, 2015 10:14

The Islamic State, The Münster Rebellion, And the Apocalypse

The crisis of Islam today, as it fragments into antagonistic factions, bears some resemblance to that of Christianity in the sixteenth century. Yet even detailed historical patterns can be like faces that we see in clouds, landscapes that we see in agate, or prophesies of the Delphic oracle.

Published on February 25, 2015 07:14

Told Me by a Butterfly

We writers constantly try to build up our own confidence by getting published, making sales, winning prizes, joining cliques or proclaiming theories. The passion to write constantly strips this vanity

We writers constantly try to build up our own confidence by getting published, making sales, winning prizes, joining cliques or proclaiming theories. The passion to write constantly strips this vanity aside and forces us to confront that loneliness and the uncertainty with which human beings, in the end, live and die. I cannot reveal my love, without exposing my vanities, and that is the fate of writers.

...more

- Boria Sax's profile

- 76 followers