Phyllis Zimbler Miller's Blog: Phyllis Zimbler Miller Author, page 8

November 29, 2017

Survivor: An Unlikely Hero

For many years in Los Angeles survivor Sol Bendik was my husband’s tailor. I learned of Sol’s amazing survivor story and wanted him to preserve it as part of Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation first-hand survivor accounts project. Yet Sol would always refuse, becoming emotional whenever I spoke about this.

Finally Sol agreed to be interviewed, but it was too late. The Shoah Foundation had closed the video interview portion of the project. Yet Sol’s story was in part amazing because he had chosen to fight back, and I wrote the Shoah Foundation a “pitch” as to why Sol’s account needed to be preserved.

My pitch worked, and I was even allowed to be present at the video recording, which was not standard procedure, in order to give Sol the courage to get past the part that always caused him to break down – where the German stuka planes strafed fleeing civilians.

Later I tried to get Hollywood interest in Sol’s story for a feature film using this pitch:

“This is an unusual saga of the incredible courage and daring of an ordinary schoolboy who becomes a man and refuses to give up his fight for justice – and then when he is successfully set for life at the age of 24 gives up everything to live in freedom. The story offers strong identification for people of all ages with an involving historical perspective of World War II not frequently portrayed.”

The following is a revision of the treatment of Sol’s story that I wrote for a film version:

PRAGUE 1938 – Sol Bendik, a 14-year-old Jewish schoolboy in a middle-class family, is oblivious to the infamous Munich Agreement turning over the Sudentenland to Germany. So he is not pleased when his father insists that the family – his parents, himself and two sisters – leave immediately for Romania. The Germans will not be happy with eating only a little his father says.

ROMANIA 1941 – A loudspeaker warns that the Germans are advancing and people should head east, farther into Russian-controlled territory. Sol and his family set off with other refugees. In the forest Sol searches for food, returning to the encampment to find everyone gone – fleeing down the road as German stuka planes appear in the sky. The planes dive and machine gun the refugees. Blood and body parts are everywhere. Sol hides behind a tree – and when the strafing is over believes that his whole family is dead.

Sol is spotted by two German soldiers. They interrogate him whether he is Jewish but he speaks in German and says he is a Volksdeutsch. They inter him at the Nikolav work camp for railroad construction. When he and another Jewish boy, Izzy, go to the fields with their German guards to get water, Sol convinces Izzy to escape through the high corn stalks.

For the next two years, constantly hungry and susceptible to capture, Sol leads himself and Izzy through German lines to the Russians. When they finally reach a Russian army camp, the officer looks at Sol and asks in Yiddish, “Are you a Jew?” The officer offers Sol and Izzy transport to safety in Moscow. Izzy accepts but Sol wants to fight. The officer sends Sol to an army training school for the Czech Brigade. After basic training Sol volunteers for parachute training school. On graduation day – Rosh Hashanah – Sol parachutes behind enemy lines into Slovakia.

At the airfield as they board the planes, Sol asks to get on the same plane as his buddy. The flight instructor refuses – there is not enough room and Sol has to take the next plane. As the planes fly towards Slovakia, the plane that Sol wanted to board explodes into a fiery ball from German antiaircraft gun fire. Once again Sol has miraculously survived.

Fueled by his need for revenge, Sol fights the Germans, stealthily attacking them wherever he finds them. When his exhausted unit is offered a return to Russia, he and others choose to remain and continue fighting. And then one day Sol is leading 12 men on skis when a wrong turn results in his capture by two Germans. Talking in German, he convinces the soldiers to take him to headquarters. On the way, he jumps over a steep cliff and falls down a mountain – but he is alive.

He evades recapture and for the third time he refuses to return to safety. Instead he joins a tank unit heading west – and he is on the first tank to enter liberated Prague. Sol is awarded the medal of honor for his valiant service in the Czech Brigade and given a pension and his own house at the age of 21. He is reunited with his father and both sisters – the fate of his mother is unknown.

PRAGUE 1948 — Sol is summoned to Communist Party headquarters and told he must become a Communist Party member. He has seen communism in Russia and is not interested in joining the party. Warned he is to be picked up, he smuggles himself without papers over the border of Czechoslovakia and eventually into France. It is 10 years since he first started running for his life.

When he reaches Paris, he calls his sister. The Communists had come for him.

Click here to read the formal proposal for the Holocaust memoir SAVIORS AND SAVIORS, in which the above firsthand account is included.

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

November 22, 2017

Safer Sex Practices Still Need Reinforcement in TV and Movies

Many years ago I worked on a safer sex initiative to encourage safer sex references and portrayal (NOT x-rated) in TV shows and movies. While I got media attention for my efforts, the initiative failed.

Let me make this very clear: I was NOT advocating for showing men and women unwrapping a condom or putting one on. I was advocating for adding references in the dialogue or visually showing a condom box to reinforce the need for safer sex.

I was just forcefully reminded of this safer sex initiative failure of mine while watching (via on demand) episode 4 of Freeform show THE BOLD TYPE, a TV series created by Sarah Watson (original episode air date of July 25, 2017).

According to imdbpro.com:

“The Bold Type” is inspired by the life of “Cosmopolitan” editor in chief, Joanna Coles. The show is a glimpse into the outrageous lives and loves of those responsible for a global women’s magazine. Their struggles are about finding your identity, managing friendships and getting your heart broken, all while wearing the perfect jeans to flatter any body type.

The show is about young people in their 20s, and clearly targeted at teens and people in their 20s.

In episode 4 the steamy sex scene — which had been built up to over several episodes — the young man says to the young woman words to the effect, “What would you like?” and she could have simply said, “Use a condom.”

But there was nothing in the scene to indicate that safer sex was practiced or that sex without protection could lead to several nasty STDs.

Why is this safer sex reference important to include? Why don’t I accept defeat and stop trying to encourage references to fictional people having safer sex?

Because, as I said years ago, teens are especially vulnerable to what they see on media. Fictional characters — and their “on screen” behavior — are often very real to teens. Including safer sex references in TV shows and movies can encourage healthy behavior in teens.

My safer sex initiative years ago failed. Yet perhaps today more of the people responsible for fictional portrayals of sex scenes will be sensitive to the responsibility they have to promote safer sex.

And if you are one of the creators of fictional portrayals, I hope you’ll take this responsibility to heart!

Click here to read post “Respect for Others: Real Life and Fiction” — relevant for this safer sex blog post and for all the sexual harassment news.

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

November 21, 2017

Understanding Why Sexual Harassment Is Still Going Strong in the U.S.

I admit it. As a long-time feminist I have been dealing with accounts of sexual harassment for many years (and my own numerous experiences of gender discrimination). I’ve just written three guest posts on using digital signage for internal communications storytelling to provide clear examples of what is — and is not — sexual harassment. And I’ve read news article after news article describing the sexual harassment charges against men in positions of power. And I still don’t get it.

What’s not to get, you ask? Men in power (and the occasional woman in power I suppose) feel entitled to say or do anything sexual, especially in the workplace. But why?

The clearest explanation of this phenomenon that I have found recently is in the November 20, 2017, New Yorker article “Letter From Silicon Valley: The Disrupters” by New Yorker staff writer Sheelah Kolhatkar.

Reading this long article, I came across Kolhatkar’s explanation of “The Al Capone Theory of Sexual Harassment” by Valerie Aurora, the principal consultant at Frame Shift Consulting, and Leigh Honeywell, a technology fellow at the A.C.L.U. The reference is to Al Capone finally being arrested for tax evasion after years of federal agents trying to get him on “serious charges, including smuggling and murder.”

“People who engage in sexual harassment or assault are also likely to steal, plagiarize, embezzle, engage in overt racism, or otherwise harm their business,” the pair wrote. “All of these behaviors are the actions of someone who feels entitled to other people’s property—regardless of whether it’s someone else’s ideas, work, money, or body. Another common factor was the desire to dominate and control other people.”

Kolhatkar goes on to say:

When I asked Aurora why she thought this connection existed, she said, “There are several reasons, but the most interesting one is entitlement. The same personality flaw says, ‘I am more important than all other people.’ ”

I’ve been pondering this explanation while more and more news stories break about powerful men getting away with sexually harassing women and how nondisclosure agreements and secret settlements have hushed up the victims.

It’s interesting how many sci fi stories deal with controlling sexual reproduction and sexual urges. Even Lois Lowry’s bestselling book THE GIVER, the 1994 Newbery Medal winner and thus considered a book for children, deals with the suppression of sexual drives.

(And this brings me to a sudden realization. In my sci fi story THE MOTHER SIEGE — can be read for free on Wattpad at http://budurl.com/MSintro — I have dealt with total control over pregnancy, yet I did not deal with controlling inappropriate sexual behavior. Obviously I need to consider this question in the planned sequel.)

What is the solution to creating safe workplace environments for women as well as all people including minorities targeted due to various prejudices?

First, language has to change. I saw this myself many years ago as a newspaper reporter who was also teaching news writing courses at Temple University’s Center City campus in Philadelphia. At that time I had a huge collection of news stories that degraded women, including a front-page article from The Wall Street Journal that identified a woman in the article as “the blonde.”

Before I could even teach my students how to accurately portray women in their news stories, I had to work through the prejudices of both the male and female students in the class. At first these students didn’t understand why the language used in news articles could hurt the real-life perception of women.

I would stand in front of the class and explain how “girl” — routinely used then to refer to adult women — was demeaning in the same article where “men” was used to refer to adult men.

Although over the years the depiction of women in news stories has improved (and kudos to The New Yorker for always describing what both men and women are wearing), there is still room for improvement.

And why is this so important? Because public language used to discuss women can lead to inappropriate language and behavior in the workplace.

When it is acceptable to joke at work that you’d like to sleep with such-and-such women, the way is paved to move on to sexual actions. And this is as true for language about minorities as it is for women.

How many times have we all heard someone say something inappropriate about a person and not corrected the speaker? I’m not suggesting we yell at the speaker, only say something such as: “That statement is inappropriate and I would appreciate your not saying it ever again.”

If we don’t speak up, we have tacitly given approval for inappropriate comments — and by extension, approval for inappropriate actions.

Only when we first change language can we begin to change the mindsets of people who, as Aurora and Honeywell wrote, “desire to dominate and control other people.”

As a first step, can we all agree to monitor our own language and the language of our colleagues and friends to help make the workplace and other places a safe environment?

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

November 20, 2017

Survivor: The Lithuanian Jew

April 25, 1975, Friday Forum – firsthand account of Judith Cohen as told in her voice by her son Michael Cohen in “Encounter With a Nightmare.”

April 25, 1975, Friday Forum – firsthand account of Judith Cohen as told in her voice by her son Michael Cohen in “Encounter With a Nightmare.”

Judith Becker was eight years old, the youngest of three children, when the Russians occupied her hometown of Kaunas (Kovno), Lithuania in 1939. (Her father died in 1938.)

Then in June 1941 at the age of 10 she was at a Russian summer camp:

The Russians used to send a whole class away for two weeks at a time. I was away at this camp when the Germans marched into Lithuania in June, 1941. The non-Jews were informed that no harm would come to them. The Jewish children were immediately separated from their non-Jewish friends.

[PZM note: The following is the part of Judith Cohen’s account that has stayed with me all these years. Whenever I look at my own diamond ring, I wonder whether I would have had the foresight to have done what her mother did.]

One evening my counselor awakened me in the middle of the night to tell me a man had a letter for me from my mother. The letter was written in Yiddish, and informed me that she had given this man her diamond ring and I was to obey him completely.

The peasant put Judith into an empty sack and filled it with hay and potatoes. He warned her that making a sound could cost her life as well as his. He drove his horse and wagon all night until arriving at his house, where he tied her up in the basement to ensure she would not run away.

They continued the next day. “Every time the wagon stopped, I felt that this was the last breath I’d ever take.” When they reached Judith’s home, her mother hugged her and broke out crying.

Later we heard by word of mouth that all of the Jewish children with whom I had shared a cabin had been taken out and shot by the Nazis.

What Judith could not know was that her mother’s foresight was only the first of a series of miracles – luck – chance that would enable Judith to ultimately survive.

A few weeks later in the middle of the night there was a knock at their door, the windows were smashed, and the Gestapo dragged them outside and threw them into trucks. “Our Christian neighbors cheered and threw rocks and stones at us.”

As the hundreds of trucks carrying Jews crossed the bridge to Shlabotka (Slobodka), she saw the students of a yeshiva carrying Sefer Torahs in their arms.

The students were thrown into a large pit and shot. As long as I live, I will never forget the moans and screams of these boys, and the men, women, and children who were thrown in with them.

When the trucks came to a stop at a group of homes, the Jews were taken off the trucks and told to take the homes.

As we ran towards the homes, they began shooting at us – several hundred lives were lost. The commandment laughed, ‘You didn’t expect such fine homes, did you?’

Judith, her older sister Rachel, brother Abe and mother Mina were now in the ghetto of Shlabotka surrounded by barbed wire and heavily guarded by SS troops. Five or six families lived in one room.

Hundreds died of starvation in the ghetto, and then came the day near the end of 1942 when Judith, her sister and mother were sent to Auschwitz. They survived the selections for the gas chamber, and in the summer or early fall of 1944 were transported to another concentration camp – Stutthof.

One day my mother was taken to the gas chamber. I clung to her as she was herded along with the others. A guard approached us and said to me, ‘You are too young to die.’ Raising his gun, he told me that if I could get out of his range before he counted to 10, I could live.

It was terrible leaving my mother like that. I remember running so very fast, hearing my mother’s last cry to me to run faster, and I saw her no more.

The death marches from the concentration camps began in the winter of 1944-45. “Anyone who could not walk was shot.” Judith’s sister Rachel had contracted typhus, and Judith “practically carried my sister the whole way.”

As the Allies flew over bombing, Judith fell into a ditch with her sister clinging to her, and by a miracle the Germans marched by without seeing them. In the morning the sisters were found by an Englishman, a Frenchman, and a Russian – POWs working on a farm owned by a top SS official.

These POWs told Judith and her sister that a price had been put on their heads and their description was being circulated. The Russian cut off their yellow stars and told the sisters to pretend they were Lithuanians who had escaped from the Elbe River.

The POWs then told the sisters to go to a nearby nunnery or the SS official on returning would have taken them to the umshlagpaltz, where everyone on the death march was taken to be massacred.

The nuns took care of the sisters even when Rachel, in her delirium from typhus, spoke Yiddish, thus revealing the sisters were Jews. But under pressure to become Catholic, and locked in their room at night supposedly for their protection, the sisters escaped through a window.

By now Judith had come down with typhus. Her sister took her to a hospital in Danzig where Judith was able to pass as a Lithuanian Catholic while Rachel found work in Danzig.

When Judith recovered, her sister brought her to the farm where Rachel worked. The German woman farm owner grossly mistreated the sisters (and was later tried by a Danish court for her inhumanity to them and sentenced to a jail term).

The woman took her own children and the sisters on a boat to Copenhagen. En route to Bremen the boat was torpedoed and sunk. The sisters clung to a plank of wood for hours until rescued and taken to Copenhagen, where they were placed in a temporary camp for German citizens.

I remember walking through the town of Swinege and seeing a woman working in her flower garden. I stopped and stood for a while watching her. When she spotted my interest, she stopped working and walked over to the fence. I asked if there were any Jews in Denmark.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘You Germans tried to kill them, but we saved many of their lives. Soon the war will be over, and you will be in concentration camps and the Jews will be free.’ Her husband came out of the house yelling at her, and pulled her back inside. I was much too frightened to tell her at that moment that I was Jewish.

Judith and her sister were liberated on May 5, 1945. The Red Cross asked if any of the people in the temporary camp were not German citizens. When Judith and her sister responded to the Red Cross, the Germans said the sisters were lying. The sisters signed their names in Hebrew to prove their identity. Later the sisters learned their brother Abe, who they thought dead, had been liberated by the Allies at Dachau.

I returned to the Danish woman who had rebuked me. She broke down crying. Her son had been hung in Copenhagen for saving two Jewish families.

The sisters spent 4 ½ years in Denmark after the war.

I cannot say enough about the Danish people. They saved countless Jews during the war while constantly risking their own lives.

Click here to read the formal proposal for the Holocaust memoir SAVIORS AND SAVIORS, in which the above firsthand account is included.

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

November 19, 2017

Savior: The Polish Countess

May 7, 1976, Friday Forum – firsthand account “God Still Has a Word to Say” by Sophie Lubomirska-Humnicka, who with her husband Count Stefan lived during WWII on two estates in Poland.

May 7, 1976, Friday Forum – firsthand account “God Still Has a Word to Say” by Sophie Lubomirska-Humnicka, who with her husband Count Stefan lived during WWII on two estates in Poland.

Countess Sophie’s account begins in August 1942 in Losice – “a sleepy little town in Eastern Poland” with a population 90% Jewish through which she and her nephew on a rescue mission drove while the Gestapo were engaged in a brutal action to murder the Jews. She and her nephew drove on to another town, Mordy, where the Gestapo were also engaged in murdering Jews. And then she and her nephew drove on to their destination – Siedlce, the district capital:

To our great horror, panic and despair, Siedlce, too, was having its great ‘action’ of ‘the final solution,’ with the only difference being that here the massacre was on a much larger scale. Literally hundreds of bodies of the dead and the dying littered the streets and the marketplace of the ghetto, where thousands of helpless Jews – men, women and children – were forced to lie on the cobblestones in the squalor of the heat and dirt, terrorized by constant shooting at them and mass killings.

Years later she was inspired to write her account while reading “The Samaritans: Heroes of the Holocaust” by Wladyslaw Bartoszewski and Zofia Lewin. Among the names of Poles who risked the lives helping Jews she saw her husband’s name: “E. Feinzilber of Tel Aviv, Israel, wrote that ‘… a rich landlord, Count Stefan Humnicki, saved from deportation 50 Jews, giving them employment on his estate and helping many to escape after the last deportation …’”

It was because of those 50 that she drove to Siedlce that day.

As she explained in her firsthand account, the Nazis had taken over much of the private property in Poland, yet they allowed her husband to keep his lands to provide food for the Germans. When a request was made to grow vegetables and they did not have enough workers, the German officer making the request agreed to assign Jews to do the work.

That day in August 1942 her husband was away when she was awakened by a phone call from Siedlce – “They’re slaughtering the Jews here and recalling all those working on private farms.”

Once in Siedlce she managed to convince a German officer not to take her Jews or she would be unable to harvest the produce she had been ordered to deliver to the Germans. He agreed to allow her to keep her Jews for now and she asked for his permission in writing.

He scribbled, signed, handed me the paper. I clutched it as if it were a life line. It was one …at least a lease on life for 50 human beings. As I walked out of the office, I felt sweat trickling down my spine, though the day was not particularly hot.

As the Jews in their part of Poland were rounded up, Countess Sophie and Count Stefan would feed those who came to their door and give the Jews money and advice on how to get into the nearby forest. Her husband was able to obtain “Christian” identification papers for some of their farm workers, who then slipped away from the estate.

I lived in constant fear for my husband’s life, but I simply could not let people be killed for the one reason – which was no reason – that they were Jews. I had to do whatever I could to save them.

Countess Sophie and her husband continued to help Jews until …

In the early hours of a cold and frosty morning in late November, 1942, some Germans, aided by the Polish police from a nearby village, unexpectedly came with a number of farm carts. The shouting and cursing armed men broke down the door and began dragging, pushing and herding the men, women and some children onto the waiting carts.

They were all taken away to Losice, where the Germans brought in all the Jews who had been rounded up in that region. From the nearby railway station they were sent to Siedlce in goods cars; and from there they went on their last journey – ‘the final solution’ – to the gas chambers of the nearby infamous extermination camp – Treblinka.

Later she learned that two young teenage girls had gotten away from the carts, but a few days later they were caught by the Germans in a nearby village and shot. One of her relatives found the foreman of the Jewish workers hiding on the estate after jumping off the speeding train just before reaching Treblinka. They arranged “Aryan papers” for him and he left for Warsaw.

Then one of her trusted employees inspected the former quarters of the Jewish workers, where he found a young Jewish boy hiding in the bread oven. The child of 10 or 12 years was persuaded to come out from his hiding place, and when he saw her with tears in her eyes, “… he said, quite calmly, ‘Please don’t cry, I know I must die.’”

She determined that he would not die – and hid Aron Perelman in a room shut off during remodeling. She took a tremendous risk for her life as well as Aron’s was at risk if he were found.

Only she and one trusted manservant saw to the boy. “We got the boy in good shape physically, but he could not get over the shock of having watched his parents’ murder.”

During the following months they were several times warned through the local grapevine that their house was to be searched by the Germans. Each time Aron was taken to the forest and then brought back afterwards.

At the end of the war she and her husband fled before the advancing Russian troops, leaving Aron in the manservant’s care. Then 30 years later she in Brazil and Aron in Israel were unexpectedly reconnected through another of her Jewish workers who had miraculously survived.

The letter Aron wrote her from Israel said in part: “… and found the person dearest to me, the one who was like a mother, the one for whom I had searched in vain for nearly 30 years. The news of your husband’s death hits me hard, may he rest in peace. I want so much to do something to keep the memory of this brave, fine man alive. Dearest Countess, if only I could see you and really express my feelings, my gratitude.”

The countess ends her firsthand account with this:

I think of the avenue in Israel I read about, lined with trees, one for every person who helped save a Jewish life during the Holocaust. There must be a great many with Polish names, names of many less fortunate than my husband and I, those who did not succeed and paid with their own lives for trying to save the lives of their neighbors, believing that we are all each other’s keepers.

Click here to read the formal proposal for the Holocaust memoir SAVIORS AND SAVIORS, in which the above firsthand account is included.

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

November 9, 2017

November 9: Remembering Kristallnacht and the Kindertransport

Kindertransport

KindertransportFor the anniversary of Kristallnacht this year I wanted to write about the Kindertransport, which, as Wikipedia explains, began after Kristallnacht:

On 15 November 1938, five days after the devastation of “Kristallnacht”, the “Night of Broken Glass”, in Germany and Austria, a delegation of British, Jewish, and Quaker leaders appealed, in person, to the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Neville Chamberlain. Among other measures, they requested that the British government permit the temporary admission of unaccompanied Jewish children, without their parents.

The result of this, as Wikipedia also explains:

The Kindertransport (German for “children’s transport”) was an organised rescue effort that took place during the nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. The United Kingdom took in nearly 10,000 predominantly Jewish children from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Free City of Danzig. The children were placed in British foster homes, hostels, schools and farms. Often they were the only members of their families who survived the Holocaust.

The December 3, 2013, Guardian article “Kindertransport, 75 years on: ‘It was fantastic to feel at last'” includes interviews with some of the elderly Kindertransport “children” and begins:

In December 1938, Kristallnacht had just rocked Nazi Germany. The pogrom killed an estimated 91 Jews, burned hundreds of synagogues and left tens of thousands imprisoned in concentration camps. Many historians see the day as the start of Hitler’s “final solution”.

Amid the horror, Britain agreed to take in children threatened by the Nazi regime. The operation was called Kindertransport, or Child Transport in English.

Seventy-five years ago this week, the first group of children arrived without their parents at the Essex port of Harwich, and took a train to London’s Liverpool Street station.

I am now working on a second memoir — SURVIVORS AND SAVIORS: A MEMOIR OF THE HOLOCAUST — and here is a section I just wrote that pertains to the Kindertransport:

Luck or Chance – A Philosophical Distinction?

I had an email exchange with a woman who has become a dear friend even though we have never spoken to each other. We first bonded online through our respective military fiction books, and now we are in almost constant email and Twitter communication.

Bonnie Bartel Latino is two weeks older than I am and in many ways couldn’t be more different. She’s a Southerner who in her life has known very few Jews. Yet her open mindedness about people is an inspiration.

She brought to my attention via Twitter a November 4, 2017, newspaper article in The Guardian about two non-Jewish British sisters who in the 1930s traveled to Germany several times to attend operas and apparently at the same time help Jews escape from the Nazi regime. That article linked to a prior Guardian article with interviews of British now-elderly adults who were saved from the Nazis via the Kindertransport (a rescueeffort to bring unaccompanied Jewish children to England from primarily Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia before WWII started).

I then emailed Bonnie that in 1988 I had hired (for a toy store in Beverly Hills for which I was a co-founder) a woman who had survived because of the Kindertransport although her parents had not survived. I wrote in email “speak”:

“What I remember most was her resentment of her parents for sending her away. She was 5, I think, from a comfortably off family in Vienna. She had never folded her own clothes before (family had maids) and now she had to do everything herself. Her older brother got to Palestine/Israel, and her older sister got across the border to Holland under fire. I’ll never forget that this woman said what saved her sister was the color of her coat that year – green – so when the Nazis starting firing (I think it was a group illegal crossing) she fell into the grass and her coat’s color saved her.”

I went on to tell Bonnie that I didn’t think I could find the woman now – I don’t remember her name – to ask her permission to use the story with her name attached. Bonnie pointed out that the woman might not still be alive.

Then Bonnie emailed:

“Even if you can’t find her again—that is a great story that could be used in the beginning to show how, so often, luck saved lives.

“Maybe luck isn’t the right word. They certainly weren’t lucky to be in that position.”

I then suggested that perhaps chance was a better word than luck.

Bonnie responded:

“Yes, chance is better.

“Just by chance her coat was the same color as the grass. Had all the grass been dead, she wouldn’t have been lucky to have on a green coat.

“Chance is the perfect word.”

The experiences of living with British families were not always positive for these rescued children, and the parents of many of these children did not survive the Nazis’ ruthlessness. Yet the hospitality of the British public and the efforts of amazing people to save these children should always be remembered. (You can read about some of these rescuers at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kindertransport)

Kristallnacht

Two years ago on November 9, 2015, I published my blog post “November 9th: Remembering Kristallnacht” and included in that post a section about Kristallnacht from my memoir of living in Germany only 25 years after the end of WWII (now renamed OCCUPYING GERMANY: ON THE FRONTLINES OF STOPPING THE RED MENACE):

I said in the memoir excerpt included in that post:

On November 9, 1970, I had been sitting in the army-supplied living room armchair reading a book about the Holocaust. I had started to read the description of a 1938 event I hadn’t heard of before — Kristallnacht — the Night of Broken Glass — a supposedly “spontaneous” action against synagogues and Jewish businesses throughout Germany and Austria (Austria’s Anschluss — annexation — to Germany took place on March 13, 1938).

During the attacks on Jewish-owned property and synagogues, 36 Jews were killed, 36 severely injured, and 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald and Dachau. After Kristallnacht the government confiscated all insurance claims and imposed a fine of 1,000,000,000 marks on the Jews.

The book explained that the “spontaneous” attacks on synagogues and Jewish businesses had in fact been carefully orchestrated by the Nazis. They used the excuse of the assassination of Ernst von Rath — the third secretary of the German embassy in Paris — by Herschel Grynszpan, the son of Polish Jews who had lived in Germany until their deportation by the Nazis to the Polish-German frontier in October 1938.

The order for the “spontaneous” action against the Jews came from the Nazi leaders gathered in Munich for the annual commemoration of Hitler’s abortive 1923 beer hall putsch.

And there in front of me on the open book page was the date the action took place — the night of November 9-10. At that moment goose bumps rose on my arms as I realized I was sitting in Munich — the heart of the Nazis’ support — on November 9, the 32nd anniversary of Kristallnacht!

Click here for this complete post.

The entire OCCUPYING GERMANY memoir (under its original title) can be read for free on Wattpad at http://budurl.com/TAintro

Finally, as I also said in my 2015 post about Kristallnacht:

In two days it will be Veterans Day. As an American Jew I am very aware of the democracy protected by our military, and I am thankful for all U.S. military personnel (and their families) in the past and in the present and in the future.

Read about my new writing project SURVIVORS AND SAVIORS: A MEMOIR OF THE HOLOCAUST

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

October 23, 2017

Chapter 1: September 1969 and September 1970

Click here for memoir introduction.

September 1969 (30 years from September 1, 1939, the infamous date when the Nazis invaded Poland, starting WWII)

On our honeymoon in Israel my husband Mitch and I took a bus tour that visited the Chamber of the Holocaust, Israel’s first Holocaust museum, on Mount Zion. I walked through the series of exhibition rooms, the walls of the rooms covered with tombstone-like plaques, each plaque memorializing one of the more than 2,000 Jewish communities destroyed by the Holocaust.

As a 21-year-old American Jew who grew up in a non-survivor community, I knew very little about the Holocaust or how many Jewish communities had been destroyed by the Nazis. I remember stopping in front of a plaque that noted the destruction of Greek Jews.

Greek Jews? I had no idea that there had been Greek Jews.

Nor did I have any expectation that exactly a year later Mitch and I would be living in Munich, Germany, the birthplace of the Nazi movement. Then just two years after our arrival in Munich, I would be the editor and publisher of first-hand survivor and savior stories for a Jewish publication in Philadelphia.

Nor did I have any premonition that, years later in Los Angeles, Mitch and I would attend the funeral of a Greek Jew, the father of a friend, who had been saved by an unknown Greek woman. The father, a young man at that time, had been taken for a task outside the camp that Greek Jews were being held in before being shipped to their deaths in Auschwitz. A young Greek woman spotted the prisoner and intentionally flirted with the Nazi guard to give the prisoner a moment to slip away. That moment saved the father’s life. Ninety percent of the Greek Jewish community wasn’t as lucky — they all perished at the hands of the Nazis.

A rabbi in Los Angeles once said to me that it took 10 days for the Greek Jews shipped in cattle train cars to arrive at Auschwitz. Then he added, “The lucky ones died before they arrived.”

September 1970

It wasn’t that difficult of a choice for my husband and myself — either Mitch signed up for an extra year of active duty Army service (and be stationed in Europe) before having an unaccompanied tour (translation: Vietnam) or go directly to Vietnam.

The only concern about this decision that my husband and I had was that most Army personnel in Europe were stationed in Germany — the country that had murdered six million of our fellow Jews and millions of other noncombatants. When I told my mother our decision she said, “Europe is so far away.” I replied, “Vietnam is further.”

In September of 1970 Mitch and I flew from Baltimore, Maryland, where he had been attending six weeks of Military Intelligence training at Ft. Holabird, to Chicago, where I would stay with my parents in Elgin, Illinois, until my concurrent travel orders came through to join him in Europe (destination still unknown).

Two hours after he flew back East he called me from Baltimore. He had just been paged at the airport and told that my concurrent orders had come through. We were going to be stationed in Munich.

Time for full confession: I had to look up Munich on the map to find where it was located in West Germany. And while I knew about Anne Frank and the six million Jews, I had no idea at this time that Munich had been the crucible for the rise of Hitler and the Nazi party.

Yet from the moment Mitch and I landed on a chartered military flight in Frankfurt and we took the train to Munich, I began to be exposed to the history I dreaded.

From taking a Jewish literature course at Michigan State University while an undergrad, I knew that cattle train cars were used to transfer Jews to their deaths in concentration camps. I also knew that men, women and children were crammed into these cars for days with no food, no water, no sanitary facilities, and very little air. Many people died during the days it took the trains to reach their destinations of death.

There’s a passage in the book THE PAWNBROKER by Edward Lewis Wallant (original copyright 1961 with a 1964 movie version) that had always haunted me since that MSU course. The fictional protagonist, a Harlem pawnbroker and survivor of the Nazi death camps, remembers when he, his wife and children were crammed into cattle cars on their way to their deaths. I recalled the scene in my memory:

The stench of human waste deposited on the train car floor for lack of sanitary facilities was so overwhelming that, when one of his beloved children slipped into the muck, the protagonist could not bring himself to reach down and lift up the child.

As Mitch and I rode in comfort in September 1970 from Frankfurt to Munich, I stared out the window at the freight cars that passed us. I knew no German, although Mitch had taken German in high school and college, and the names of the towns through which we passed at that time meant nothing to me.

What did register is that we arrived at the Munich train station on a Sunday in the midst of Oktoberfest with drunken gastarbeiters milling around us and our eight suitcases to be taken somewhere. That somewhere was elusive as Mitch’s orders to report to the 18th Military Intelligence Battalion didn’t include an address.

Mitch managed to snag a taxi, and we got us and the eight suitcases loaded into it. To the question of “Wohin?” Mitch said, “Amerkanischer kaserne.”

Luck was with us at this point because, as we later learned, the German authorities had convinced the U.S. military to move units out of Munich ahead of the scheduled 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Therefore in September 1970 only one American base remained in Munich — McGraw Kaserne — that of the 66th Military Intelligence Group.

We arrived there only to be told that 1) the 18th MI Battalion didn’t have a duty officer on weekends so the 66th MI Group duty officer was the correct officer to whom to report and 2) we had to go back downtown to near the train station to the army transit hotel.

Then once we got to the transit hotel, accompanied by my raging cold — a tall young officer appeared who said he and his wife were our sponsors and he had come to take us to their housing unit for dinner. This housing unit turned out to be almost adjacent to the 66th MI Group headquarters, so back we went again.

On the way there I could only worry about the pork that we might be offered because, even though Mitch and I didn’t observe the laws of keeping kosher, I didn’t eat pork. Thankfully the officer and his wife were Southerners — and served us fried chicken.

Within days Mitch had been assigned to work on the Sociological Desk at the 18th — one of four subject desks — under a non-Jewish Department of the Army civilian, Lucian — Lutz — Kempner, who had his own Nazi victim story including being kidnapped by the Gestapo.

Two weeks later a second Jewish officer and his wife arrived in Munich, and he would be assigned to work for the Jewish Department of the Army civilian, Henry Einstein, who as a teen-age Jew had gotten out of Germany in time and now headed the Military Geography Desk.

The stories of these two men were bound together through Lutz’s father, Robert Kempner, who had served as assistant U.S. chief counsel during the Nazi War Crimes Trials at the Internal Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, where Henry Einstein had worked as a clerk for Lutz’s father.

We would learn the stories of these two men against the backdrop of living in Germany surrounded by thousands of former Nazis.

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

October 17, 2017

Harvey Weinstein and Ongoing Sexual Harassment

While the media engage in featuring multiple stories of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual predator behavior, what often gets lost is how this type of heinous behavior goes on all the time even in so-called civilized countries.

In my opinion the reason that this goes on is that — as with anti-Semitism, racist prejudice and a host of other despicable mindsets and behaviors — there are large segments of these civilizations that think these attitudes are acceptable.

And this is because we all allow these attitudes to exist, partly in the language that we all use.

Note that I am not advocating for language police. I am advocating for being conscious of what we are allowing to be said in our work places and social circles.

How many of us wince when we hear a sexual joke that describes women as “asking for it”? Yet do we say to the joke teller, “That is inappropriate and please do not say such things again”?

In my current role as Content Marketing Strategist at a digital signage company, I wrote a blog post inspired by the Weinstein media stories. The post described how internal communications digital signage can be used to curb inappropriate sexual language and behaviors. My boss said no to publication because he felt the post was too controversial, which it may have been for a business blog. (I did tone it down and perhaps it will now get the greenlight to be published.)

Yet the main premise of my post is very valid. People — and especially employees — need to be continually reminded of what is — and is not — acceptable behavior.

Having new employees sign a form that they understand what is appropriate behavior — and then never being reminded again of this behavior standard — is close to worthless. With today’s 24/7 digital bombardments, how many of us can even remember what we had for lunch two days ago?

To change harmful attitudes, and by extension harmful behaviors, we all need to be continually reminded of what is appropriate and what is not.

And here, for example, is where digital signage used for internal communications in office locations can continually remind people of what is acceptable. This content need not be boring — cute cartoons can get across the message. And companies can hold internal contests for cartoon submissions.

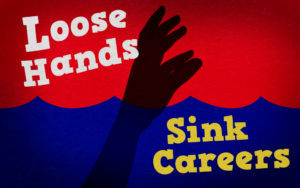

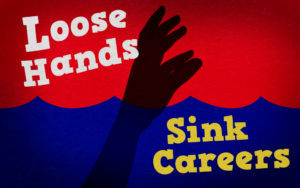

In the unpublished company post I wrote about the World War II slogan LOOSE LIPS SINK SHIPS. Then I suggested the slogan LOOSE HANDS SINK CAREERS.

If we do not want to see continuing media stories of sexual predator behavior by people in power, then we all need to change our mindsets. And that does not mean signing a form once. It means continually working on changing attitudes and behavior all around us.

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

October 8, 2017

Holocaust Memoir SURVIVORS AND SAVIORS — New Writing Project

Stolpersteine from Berlin

Every survivor’s story is one of miracles — and luck.

I wrote that sentence in my mind as I stood facing the open Torah Ark for Yom Kippur on September 30, 2017, during the Neilah service in the final hour of the Day of Atonement fast (no food or even water). At that moment I resolved that I needed to preserve the survivor and savior stories I personally knew.

Why does one moment in time light a fire under motivation — to do what I probably should have done years ago?

Perhaps this motivation started with the Alternative for Deutschland’s strong and frightening win in Germany’s Bundestag election a week earlier.

Or perhaps the recent discussion of the book club to which I belong tipped me over the edge. We had read Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s book MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANING. The discussion leader talked about Frankl’s thesis of willpower to survive, and I kept saying it was luck no matter how strong the willpower to survive.

And I should know about the role of luck due to all the survivor and savior stories that haunt me.

In the beginning I was a second-generation-born American Jew in a small town (Elgin, Illinois) Jewish community with only one woman I knew whose family had gotten out of Germany. In later years I would appreciate that this woman’s niece, Sherry Lansing, a former CEO of Paramount Pictures, was the first woman to head a major Hollywood movie studio. Lansing’s mother, her aunt, and their parents had gotten out of Germany “in time” — meaning in this book “before the war,” which started on September 1, 1939, when the Nazis attacked Poland.

I remember the moment as a teen that I first read about Anne Frank in a newspaper article spread out on our dining room table. At that time I knew very little about the Jews, the Gypsies and the millions murdered by the Nazis.

Then in September 1970, only 25 years after the end of WWII, my husband and I were stationed in Munich with the U.S. Army. As we took the train from Frankfurt to Munich, I looked out the window at the railroad freight cars and wondered whether these were the same cars that had carried the Jews to their deaths.

Once in Munich my husband worked under a non-Jewish Department of the Army civilian who had been imprisoned in Dachau before the war and then released. The man had worked for the Americans undercover in Italy during WWII and his father had been a prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials for Nazi war criminals.

In the same U.S. Army intelligence unit was a Jewish Department of the Army civilian who had gotten out of Germany in time and who had returned with the U.S. Army and served as a translator at the Nuremberg Trials. (His father had been murdered in Auschwitz, and his mother survived by claiming French citizenship due to the vagaries of Alsace, where she had been born.)

About two months after we arrived in Munich, while reading a book in my army-supplied housing unit, I first learned about Kristallnacht, realizing with horror that this day of November 9, 1970, was the anniversary of that infamous attack on Jews, synagogues and Jewish stores in Germany and Austria on the night of November 9-10,1938. (Austria was annexed to Germany on March 12, 1938.)

Living in Munich, we several times visited nearby Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp, opened only two months after Hitler took power in January of 1933. And in Germany we met our first survivors and had our first up-close-and-personal Holocaust experiences.

While in Germany we decided to start keeping kosher when we returned home to the U.S. This decision was influenced by the emotional toll of living in Germany only 25 years after the decimation of such a vast number of European Jews. Although my husband and I were born too late to save any of the murdered Jews, we could choose to live a Jewish lifestyle in support of what had been ripped from them.

In May of 1972 my husband and I returned to the U.S. when his active duty commitment was completed. A few months later I became the editor of Friday Forum, the monthly literary supplement of the weekly Jewish Exponent newspaper in Philadelphia.

During six years in that position I edited and published first-hand accounts of Holocaust survivors and saviors as well as interviewing in person both French Nazi hunter Beate Klarsfeld and Ruth Kluger, the savior of many Rumanian Jews who she helped smuggle into then-Palestine. I also wrote reviews of numerous Holocaust fiction and nonfiction books.

These and other Holocaust stories I know continue to haunt me. In my family the frequent refrain when I mention something in a conversation is, “Does it have to be the Holocaust?” And the answer often is yes.

Let’s return to the timeline of now in 2017:

The book club discussion of MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANING was September 11.

On the evening of September 21, the beginning of the second day of Rosh Hashanah this year, one of our dinner guests mentioned he has a friend, a Dutch Jew, for whom Anne Frank as a young teenager babysat. The Dutch family hiding our guest’s friend as a baby was denounced. As the Gestapo arrived at the family’s home, the maid threw the baby over the fence, saving him — and probably the family members hiding him — from death at the hands of the Nazis.

I told our Rosh Hashanah dinner guest that, during the time my husband and I lived in Munich, the Anne Frank House had been at risk of closing for lack of funds. I still had the article from the European edition of the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes about this risk of closure. I also had a carbon copy of the letter I typed to accompany donated funds to the Anne Frank House from the few of us American Jews in Munich at that time.

The Alternative for Deutschland’s political victory in federal elections to elect the members of the 19th Bundestag took place on Sunday, September 24. (My younger daughter and I had seen this far-right party’s political posters in Berlin in August of 2016.)

Then the moment in Neilah on September 30 when I realized that, by writing a memoir, I could preserve so many of the stories that haunt me — both those of the survivors and of the saviors.

The next day of October 1 I told my friend Susan Chodakiewitz, with whom I have been working for years on a Holocaust project about her long-time personal friend Israeli Nazi hunter Tuviah Friedman, that I could wait no longer. The way to preserve these stories was a memoir that I would start to write immediately. (And this memoir would include descriptions of Holocaust-related media including books, movies and other digital content with a reference list at the end of the memoir.)

Only a few hours after I wrote the beginning of this memoir introduction on October 2, my younger daughter brought home as a gift for me a hardcover illustrated book she had received at work — BRUNDIBAR — written by Tony Kushner and illustrated by Maurice Sendak.

She handed it to me with the words, “It has to be about the Holocaust.”

The book is based on a Czech opera for children performed 55 times by the children of Terezin, the Nazi concentration camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia also known as Theresienstadt.

I mentioned to her that, when she and I had seen a special exhibit on Maurice Sendak several years ago at the Jewish Museum in New York City, I remembered reading that, on the morning of his Bar Mitzvah, his family had learned of the murder of his relatives in Europe by the Nazis. The juxtaposition of hearing such horrendous news on the morning of one’s Bar Mitzvah had stayed with me.

My daughter immediately looked up Maurice Sendak on Wikipedia. The entry began:

“Maurice Bernard Sendak (/ˈsɛndæk/; June 10, 1928 – May 8, 2012) was an American illustrator and writer of children’s books. He became widely known for his book Where the Wild Things Are, first published in 1963. Born to Jewish-Polish parents, his childhood was affected by the death of many of his family members during the Holocaust.”

I looked at his birth date — June 10, 1928; 13 years later, on the night of June 21-22, 1941, the Nazis broke the nonaggression Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Russia and Germany by launching a massive attack on the Soviet positions in Eastern Poland. The Nazis’ Einsatzgruppen death squads wiped out the Jews in the path of the Nazis’ lightning advances into Russia.

Bar Mitzvah dates are often based on a boy’s Jewish lunar calendar birth date, which fluctuates from year to year in relation to the secular calendar birth date. Thus if Sendak’s Bar Mitzvah had been held two or three weeks later than June 10, it would explain the likelihood of receiving the horrific news on the morning of his Bar Mitzvah.

Finally, the question of why both survivors and saviors?

In 2017 the number of each group still living is very small. I had Shabbat dinner in a sukkah on October 6, and the mother of one guest was a survivor still alive at 94. These firsthand accounts will soon be forever gone, leaving a huge void for Holocaust deniers to rush to fill.

Equally important is to preserve both sides of the harrowing experiences. In these pages I will relate many stories of which I was the midwife of their recounting, two of which are these:

The Jewish mother who gave her diamond ring to a Polish peasant to bring her daughter back from a Jewish summer camp in Russia in June 1941 when the Nazis broke their nonaggression pact with the Russians. While this act was only the first of a string of miracles that ultimately saved her daughter’s life, to this day I can’t look at my own diamond ring without wondering whether I would have had the foresight to have done this. (The Nazis wiped out every person in that children’s summer camp.)

The Polish countess who hid Jews on her estate until the Nazis came for them. She believed a small boy had been among the Jews murdered, only to learn through a chance encounter many years later that he had hidden in the bread oven on the estate and thus survived.

Now let’s begin these stories of both survivors and saviors.*

Phyllis Zimbler Miller

Beverly Hills, California

October 8, 2017

*To be continued.

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

September 24, 2017

Optimistic Signs for Females in STEM

Recently there have been several positive signs of encouraging girls and women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) careers:

Recently there have been several positive signs of encouraging girls and women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) careers:

1) Girls Who Code

First, news from GirlsWhoCode.com:

Girls Who Code has teamed up with Penguin to release 13 books for girls about computer science and coding. The first books are out now and immediately hit The New York Times Best Seller List. You can also expect to see a coding-themed journal, activity book, board books, and more!

The first two books were published on August 22, 2017 — one fiction and one nonfiction — and although the books appear aimed at girls ages 8 to 12, I immediately bought both books.

The fiction one is THE FRIENDSHIP CODE #1 by Stacia Deutsch. It is a typical Middle Grade novel with the teen girls solving a mystery about coding.

One important note: There is an error on page 119 of the print edition. The 3 should be 4 so that the correct coding line reads:

string friend_name_4 = “Erin”;

I’m now reading the nonfiction book GIRLS WHO CODE: LEARN TO CODE AND CHANGE THE WORLD by Reshma Saujani, founder of Girls Who Code.

On the Girls Who Code site there is this explanation of why the organization’s mission matters:

Computing is where the jobs are — and where they will be in the future, but fewer than 1 in 5 computer science graduates are women.

The organization also offers school club programs and summer immersion programs.

2) Project MC² series on Netflix

I just came across this series PROJECT MC² on Netflix featuring trendy teen girls doing science experiments. I immediately bought the accompanying book THE PRETTY BRILLIANT EXPERIMENT BOOK by Jade Hemsworth.

Here from YouTube is one such experiment:

3) Beverly Hills 8th grader Leia Gluckman finalist in national STEM competition

On September 22, 2017, the Beverly Hills Courier carried this front-page news:

When Beverly Vista student Leia Gluckman entered the district Science Fair last year as a 7th grader, she knew exactly what she wanted to create — a product to help the homeless. A volunteer at the teen homeless shelter Safe Place For Youth in Venice [California] since she was 4 years old, Leia said that helping people live better lives has always been in her heart.

After several experiments and 13 difference formulas, Leia successfully created a powder cleanser that would work as a toothpaste, a dry shampoo and a body powder — the perfect all-in-one cleanser for someone with very little.

Leia was named a Top 30 finalist in the Broadcom MASTERS (Math, Applied Science, Technology and Engineering Rising Stars), “a prestigious national Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) competition for middle school students.”

An important paragraph in the Beverly Hills Courier news story:

For the second year in a row, there will be an equal number of male and female finalists competing. Ten of the finalists, selected from a record high of 2,499 applications by a panel of scientists and engineers, are from California.

FYI — The mission of the Broadcom Foundation is:

Broadcom Foundation empowers young people to be STEM literate, critical thinkers and college and career-ready by creating multiple pathways and equitable access to achieve the 21st century skills they need to succeed as engineers, scientists and innovators of the future.

P.S. Film2Future for under-served female and male teens

And if you are looking to donate to a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization that helps under-served female and male teens in their career paths, check out Film2Future.com

© 2017 Miller Mosaic LLC

Phyllis Zimbler Miller (@ZimblerMiller) has an M.B.A. from The Wharton School and is the author of fiction and nonfiction books/ebooks. Phyllis is available by skype for book group discussions and may be reached at pzmiller@gmail.com

Her Kindle fiction ebooks may be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszimblermiller — and her Kindle nonfiction ebooks may also be read for free with a Kindle Unlimited monthly subscription — see www.amazon.com/author/phylliszmiller

Phyllis Zimbler Miller Author

- Phyllis Zimbler Miller's profile

- 15 followers