Terry Teachout's Blog, page 98

February 27, 2013

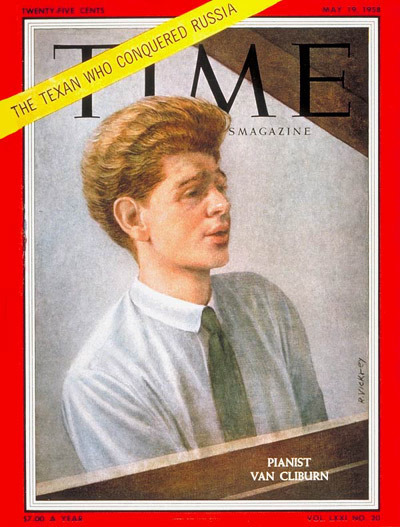

TT: Van Cliburn, R.I.P.

Fewer and fewer people can say that they heard Van Cliburn play a solo recital. I did, in Kansas City in 1978, not long before he retired from the concert stage, and it was one of the most impressive musical experiences of my life.

Not that he did anything unusual: the program consisted of familiar pieces by Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin, and Debussy that he'd recorded for RCA and played regularly from adolescence onward, and he interpreted them in a very "centric" way, devoid of mannerisms of any kind. Yet there was nothing impersonal about the way he played them. His tone was huge and rich, his rubato restrained and sensitive, his technique faultless. He was, I realized at once, a true artist.

Not that he did anything unusual: the program consisted of familiar pieces by Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin, and Debussy that he'd recorded for RCA and played regularly from adolescence onward, and he interpreted them in a very "centric" way, devoid of mannerisms of any kind. Yet there was nothing impersonal about the way he played them. His tone was huge and rich, his rubato restrained and sensitive, his technique faultless. He was, I realized at once, a true artist.

It wasn't enough, of course. He'd become unimaginably famous at the age of twenty-three after winning the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. Moreover, fame had complicated his life to a degree scarcely more imaginable, for Cliburn, who died today at the age of seventy-eight, was a deeply closeted Eisenhower-era homosexual who lived in Texas and went to church every Sunday. To be a celebrity under such circumstances was an invitation to unhappiness. It didn't help that he had an inexplicable incuriosity about music. The pieces that he learned as a student were for the most part the pieces he played in concert for the rest of his career. He was great, but he stopped growing, and before long he stopped performing as well.

Now that he's gone, it seems safe to say that a frank biography will soon be published, one that seeks to disentangle the sad complexities of his private life. I'll read it, but I'll be more inclined to revisit his records, a fair number of which are as good as any that have ever been made by a classical pianist. (I especially like this one .) In the long run, that's what will matter most about Van Cliburn. The rest, as they say, is history.

* * *

Tim Page's Washington Post obituary is here .

Anthony Tommasini's New York Times obituary is here .

Van Cliburn plays Liszt's Twelfth Hungarian Rhapsody, one of the few works in his concert repertoire that he never recorded commercially:

Not that he did anything unusual: the program consisted of familiar pieces by Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin, and Debussy that he'd recorded for RCA and played regularly from adolescence onward, and he interpreted them in a very "centric" way, devoid of mannerisms of any kind. Yet there was nothing impersonal about the way he played them. His tone was huge and rich, his rubato restrained and sensitive, his technique faultless. He was, I realized at once, a true artist.

Not that he did anything unusual: the program consisted of familiar pieces by Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin, and Debussy that he'd recorded for RCA and played regularly from adolescence onward, and he interpreted them in a very "centric" way, devoid of mannerisms of any kind. Yet there was nothing impersonal about the way he played them. His tone was huge and rich, his rubato restrained and sensitive, his technique faultless. He was, I realized at once, a true artist.It wasn't enough, of course. He'd become unimaginably famous at the age of twenty-three after winning the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at the height of the Cold War. Moreover, fame had complicated his life to a degree scarcely more imaginable, for Cliburn, who died today at the age of seventy-eight, was a deeply closeted Eisenhower-era homosexual who lived in Texas and went to church every Sunday. To be a celebrity under such circumstances was an invitation to unhappiness. It didn't help that he had an inexplicable incuriosity about music. The pieces that he learned as a student were for the most part the pieces he played in concert for the rest of his career. He was great, but he stopped growing, and before long he stopped performing as well.

Now that he's gone, it seems safe to say that a frank biography will soon be published, one that seeks to disentangle the sad complexities of his private life. I'll read it, but I'll be more inclined to revisit his records, a fair number of which are as good as any that have ever been made by a classical pianist. (I especially like this one .) In the long run, that's what will matter most about Van Cliburn. The rest, as they say, is history.

* * *

Tim Page's Washington Post obituary is here .

Anthony Tommasini's New York Times obituary is here .

Van Cliburn plays Liszt's Twelfth Hungarian Rhapsody, one of the few works in his concert repertoire that he never recorded commercially:

Published on February 27, 2013 14:23

February 26, 2013

TT: Snapshot

John Barrymore speaks Hamlet's soliloquy in Playmates (1941), co-starring

Kay Kyser

. This was Barrymore's final film appearance. He died of alcoholism in 1942:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Published on February 26, 2013 21:00

TT: Almanac

"Only the truly great actor can be ridiculous on one night, and sublime on another."

Ronald Harwood, Sir Donald Wolfit: His Life and Work in the Unfashionable Theatre

Ronald Harwood, Sir Donald Wolfit: His Life and Work in the Unfashionable Theatre

Published on February 26, 2013 21:00

February 25, 2013

TT: Lookback

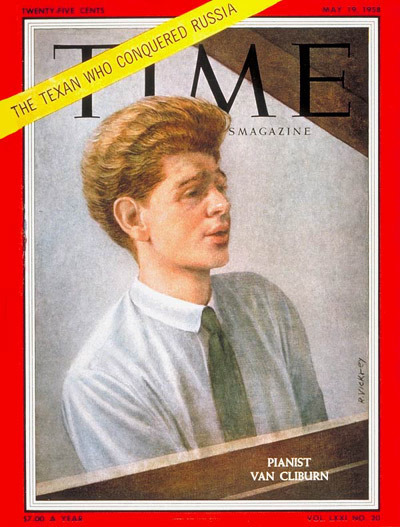

From 2004, a memory of watching Lost in Translation with my septuagenarian mother:

From 2004, a memory of watching Lost in Translation with my septuagenarian mother:Somewhat to my surprise, she liked it, though she initially found Sofia Coppola's elliptical style of storytelling a bit hard to follow. (Gen-X moviegoers suckled on MTV take jump cuts for granted, but most people born before 1950 or so are accustomed to films in which the plot elements are laid out fairly straightforwardly.) In addition, it hit me after about 10 minutes that she didn't know what jet lag was...

Read the whole thing here .

Published on February 25, 2013 21:00

TT: Almanac

"If you try to write 'good lines' you'll likely wind up with strings of dumb, unconnected applause lines. The audience will probably applaud--crowds of supporters are dutiful that way, and people want to be polite--but they'll know they're applauding an applause line, not a thought, and they'll know they're enacting enthusiasm, not feeling it. This accounts for some of the tinniness of much modern political experience."

Peggy Noonan, A Sunday Thought ("Peggy Noonan's Blog," The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 3, 2013)

Peggy Noonan, A Sunday Thought ("Peggy Noonan's Blog," The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 3, 2013)

Published on February 25, 2013 21:00

CD

Paul Moravec,

Northern Lights Electric

(BMOP/sound). Two large-scale concerti by my Pulitzer-winning operatic collaborator, the 2008 Clarinet Concerto (played by David Krakauer) and Montserrat: Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, composed in 2001 (played by Matt Haimovitz), accompanied by the title track, an impressionistic chamber-music octet that he rescored to brilliant effect for full orchestra in 2000. I suppose I'm biased--I think that Paul is one of this country's very finest composers--so I'll say no more than that if you don't know his music, this exceedingly well-played CD, which also features Gil Rose and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, is an ideal place to start (TT).

Published on February 25, 2013 05:34

PLAY

All in the Timing

(Primary Stages, 59E59 Theatres, 59 E. 59, extended through Apr. 14). A twentieth-anniversary off-Broadway revival of the program of six one-act comedies, by turns surreal and poignant, that first put David Ives on the map of American theater. I didn't see the 1993 production, but I can't imagine how it could have been better than this glittering version, perfectly staged by John Rando, Ives' frequent collaborator, and acted with colossal éclat by five young actors who fit together like the pieces of a platinum-plated jigsaw puzzle (TT).

Published on February 25, 2013 05:34

February 24, 2013

TT: Almanac

"If it's a musical, and it's not about love, I don't see the point."

David Ives (quoted in Pia Catton, "Parsing a Playwright's Universal Language," The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 3, 2013)

David Ives (quoted in Pia Catton, "Parsing a Playwright's Universal Language," The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 3, 2013)

Published on February 24, 2013 10:45

TT: Just because

Chet Atkins plays "Vilja" and "Say Si Si" on Ozark Jubilee in 1958:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Published on February 24, 2013 10:45

TT: Yours in haste

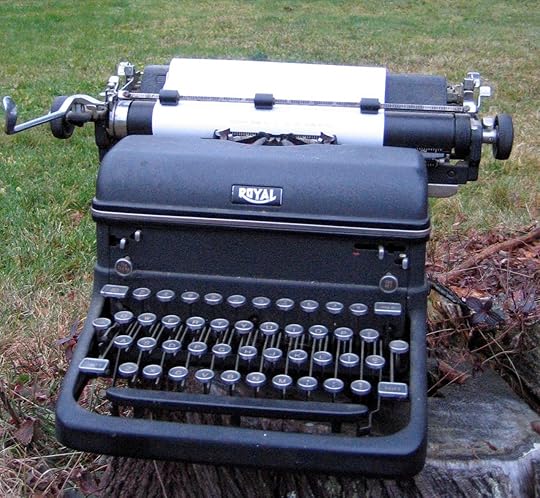

I spent the first decade of my life as a professional writer using a big black Royal manual typewriter that had once belonged to my mother. (I called it my "acoustic typewriter.") I wrote a couple of hundred pieces, most of them concert reviews for the Kansas City Star, on that ancient but impeccably reliable machine. Then, in 1987, I bought an IBM PC, and since then I've written exclusively on computers. Over the years I've owned a half-dozen personal computers, on which I've written six books and edited three essay collections.

I spent the first decade of my life as a professional writer using a big black Royal manual typewriter that had once belonged to my mother. (I called it my "acoustic typewriter.") I wrote a couple of hundred pieces, most of them concert reviews for the Kansas City Star, on that ancient but impeccably reliable machine. Then, in 1987, I bought an IBM PC, and since then I've written exclusively on computers. Over the years I've owned a half-dozen personal computers, on which I've written six books and edited three essay collections.Of late I've been wondering exactly what effect the coming of the computer has had on my writing life. Is it easier, or harder?

I realized soon after I bought my first computer that it cut much of the waste motion out of the process of writing. I'd say that I write twice as fast on computers as I did on my manual typewriter. Instead of using that spare time for purposes of leisure, though, I now write roughly twice as much. To be specific, I write a hundred thousand words a year for The Wall Street Journal and Commentary, an amount roughly equal to a medium-sized book. My blog entries probably come to another fifty thousand words, more or less. I publish a book every two or three years, and since 2009 I've also written three plays and three opera libretti. That's a lot of words, and I know that I couldn't churn out nearly as many of them on a typewriter.

Another element of this increased productivity is that computers make it possible for me to do serious research at my desk instead of going to libraries. It took me just three years to write Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington, as opposed to the decade that went into The Skeptic: A Life of H.L. Mencken, virtually all of which was written before I started using Google. It takes me three hours to write a Wall Street Journal drama column, and my guess is that without Google, I'd have to spend another hour or so sifting through my home library in search of relevant information.

All of which suggests that the easier-harder dichotomy is a false one. Computers make it easier to write, but they also facilitate greater productivity, which makes my life harder and more stressful. And that inevitably leads me to ask: ought I to be writing as much as I do? Might I be writing better if I wrote less?

For the most part, we write as we must, not as we will. I've always been a fast writer, just as I'm a fast reader, and I take it for granted that this facility is at best a mixed blessing. It is, however, part of my impatient nature, and I accept it as such. I rarely slave over my Wall Street Journal drama columns: they just come out. Nor do I write them for the ages. They're journalism, about which H.L. Mencken said the last word in the preface to A Mencken Chrestomathy:

What the total of my published writings comes to I don't know precisely, but certainly it must run well beyond 5,000,000 words. A good deal of it, of course, was journalism pure and simple--dead almost before the ink which printed it was dry.

I'm not saying that I don't take my drama columns seriously. I do, very much so. But I also accept the limitations of the medium in which I work. I doubt that I'll ever collect my Wall Street Journal reviews, any more than I'd publish a volume of my blog posts. I prefer to transform the very best of them into longer, more considered essays, just as Mencken used his newspaper journalism as not-quite-raw material for his magazine articles and books.

I am, however, dodging the issue. Could I be a better writer if I wrote less and thought more? Does my computer-driven life contain enough room for contemplation?

I am, however, dodging the issue. Could I be a better writer if I wrote less and thought more? Does my computer-driven life contain enough room for contemplation?The theologian Josef Pieper spoke to this very point in a beautiful little book called, appropriately enough, Leisure, the Basis of Culture :

Leisure is a form of silence, of that silence which is the prerequisite of the apprehension of reality: only the silent hear and those who do not remain silent do not hear. Silence, as it is used in this context, does not mean "dumbness" or "noiselessness"; it means more nearly that the soul's power to "answer" to the reality of the world is left undisturbed. For leisure is a receptive attitude of mind, a contemplative attitude, and it is not only the occasion but also the capacity for steeping oneself in the whole of creation.

This isn't the first time that I've worried about such matters. I blogged about them three years ago, at which time I asked myself (and you) the following question: "What has vanished along the way, at least for the moment, is the wasted time that is never wasted, the fallow idleness that eventually bears unforeseen fruit. Will my imagination dry up a year from now because I was too busy to daydream today?"

That's still a good question. On the other hand, it's also true that since I wrote those words, I've become a part-time playwright, a development that I never contemplated in 2010. In fact, I wrote those words just before I started writing the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf. So I must be doing something right--but is it right enough?

I took what I believe to be a step in a more fruitful direction by going to the MacDowell Colony last summer and spending five weeks in semi-seclusion, working on Duke and Satchmo at the Waldorf. It was the most productive period of my life. Was it a contemplative period? Yes and no. I worked like a demon, but I did it in a peaceful rural setting, completely divorced from my hectic urban routine, and I spent a fair amount of my time there walking, thinking, and talking to other artists, two of whom became close and valued friends.

I took what I believe to be a step in a more fruitful direction by going to the MacDowell Colony last summer and spending five weeks in semi-seclusion, working on Duke and Satchmo at the Waldorf. It was the most productive period of my life. Was it a contemplative period? Yes and no. I worked like a demon, but I did it in a peaceful rural setting, completely divorced from my hectic urban routine, and I spent a fair amount of my time there walking, thinking, and talking to other artists, two of whom became close and valued friends.Should I be doing more of that? Undoubtedly, though I don't know how to work it yet. What I do know is that I want to write more plays, and what I fear is that I'll find that increasingly difficult to do unless I find a different way to lead my life. But I may be wrong. I may be, like Duke Ellington, a person whose nature demands that he be constantly active. As I wrote in Duke:

Ellington composed as he lived, on the road and on the fly. He wrote his pieces in hotel rooms, Pullman cars, and chartered buses, then rehearsed them in the recording studio the next afternoon or on the bandstand the same night. He had little choice but to do so, for he was a professional wanderer who traveled directly from gig to gig, returning to his New York apartment, he said, only to pick up his mail. It would no more have occurred to him to take time off to polish a composition than to go on a month-long vacation.

I don't know that I like the sound of that kind of life. It is, however, the life that I currently lead, for better and worse.

As for my acoustic typewriter, I gave it back to my mother, who used it to address envelopes. So far as I know, it still resides at her old house in Smalltown, U.S.A. It outlived her, and I wouldn't be surprised if it outlives me. Unlike human beings, or personal computers, it was built to last.

Published on February 24, 2013 10:45

Terry Teachout's Blog

- Terry Teachout's profile

- 45 followers

Terry Teachout isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.