Marcia Biederman's Blog, page 5

October 12, 2019

Wall Street Journal Reviews “Scan Artist”

One of the first major news outlets to raise questions about Evelyn Wood’s speed-reading method ran a review of my book Scan Artist on its Opinion page today. It’s good to see the WSJ again describing Wood’s claims as “preposterous.” The book includes portions of my interview with Ira West, the young journalist who raised questions about the effectiveness of the method back in 1967. As the Journal wrote then, some large corporations that had enrolled employees in Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics courses had quietly stopped doing so after discovering that the instruction was ineffective. The same was true of the US Air Force Academy.

July 31, 2019

When Congress Thought It Could Speed-Read

By Marcia Biederman, author of SCAN ARTIST: HOW EVELYN WOOD CONVINCED THE WORLD THAT SPEED-READING WORKED, to be released by Chicago Review Press on Sept. 3, 2019.

If the redacted version of Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller’s report had been released during the Kennedy era, everyone would have read already. Or, rather, they would have claimed they had. With JFK in the White House, reportedly gulping text at breakneck speed, a simmering speed-reading craze ignored scientific skepticism and reached a rapid boil.

If Mueller’s report does nothing else, its reception marks the end of a longstanding national delusion. In organizing a marathon read-aloud of its contents last week, House Democrats recognized that each unredacted word deserves careful consideration. From the early 1960s until not very long ago, that event would have seemed hopelessly old-school. Two U.S. presidents and a number of senators, notably Democrats, claimed the ability to read at least a thousand words a minute without sacrificing comprehension. At that pace, the special counsel’s 448-page would be well digested within two hours, not 17 hours and 25 minutes – the typical time it takes to read, according to Kindle.

As ridiculous as those claims may seem today, they once triggered national anxieties. A Texas newspaper warned in 1961, “If you can’t read and understand 3,000 to 4,000 words a minute, you’re definitely ‘out’ of the New Frontier.” The low end of that range is about ten times the normal reading rate of most people, including those with higher education. However, as the news item pointed out, help was available. A so-called revolutionary reading system called Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics promised to triple the average mortal’s rates in a matter of weeks. The most adept and applied students could expect to achieve warp speeds, or so they were told.

Professing to belong to the latter group were four senators. William Proxmire of Wisconsin, Herman Talmadge of Georgia, and Stuart Symington of Missouri enrolled in an Evelyn Wood class in Washington. Graduating from the 30-hour course, the three Democrats gushed about their progress on an ABC television news show. Proxmire’s outlandish claim of reading at 20,000 words per minutes was reported by papers across the nation, and testimonials from all three Democrats ran for years in Evelyn Wood print ads, joined by that of a Republican, Senator William Bennett of Utah.

Evelyn Wood, the company founder, was a native of Bennett’s state and had already taught some of his college-aged sons. As a part-time University of Utah instructor, she’d revamped a previously unnoticed reading-improvement course, telling a newspaper reporter she could multiple reading rates tenfold. Soon, students were camping out in registration lines to secure a spot in her class, or so said Wood, an unreliable narrator.

Rapid reading courses, as they were known, were nothing new then. Universities routinely offered them, competing with a patchwork of proprietary schools. By 1957, the Wall Street Journal had already noted the burgeoning sales of related gadgets, classes, and publications. But the fragmented industry lacked a coherent message and a dominant brand until Wood came to Washington with extravagant promises. Her trademarked method dispensed with the machinery favored by competitors. Instead, she had students sweep fingers across pages, with eyes following. With practice, she promised, they’d learn to ingest ideas and not words. Comprehension would improve rather than suffer, Wood assured.

Assumptions about age, race, and gender seemed to place Wood beyond reproach. White, middle-aged, and conservatively dressed, she was billed as a schoolteacher, though she’d spent relatively little time in conventional classrooms. Having staged religious pageants at the Mormon Tabernacle, she was adept at recruiting wholesome-looking juveniles to demonstrate her system at sales sessions, academic conferences and on TV talk and game shows. That skill served her well as she parried the legitimate skepticism of her methods arising from universities, reading experts, consumers, and former colleagues. Her mild manner and the youth of her assistants made debunkers seem like bullies, and her lawyer raised the threat of a defamation suit.

Not to be outdone by senators, two dozen US representatives invited an Evelyn Wood instructor to set up shop in a House hearing room. Most were Democrats eager to emulate JFK, who’d once taken a few speed-reading classes offered by another company before dropping out to continue on his own at a reported 1,250 words per minute. After Kennedy’s death, Evelyn Wood said he’d invited her to the White House to teach his aides and joint chiefs of staff. More likely, some chose to take the course commercially. Without endorsing Wood publicly, the reader-in-chief clearly approved of her approach. In the transcript of a telephone recording recently released by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, the president urged his brother Ted, newly elected to the Senate, to work harder at an Evelyn Wood class organized, under the younger Kennedy’s leadership, in the upper chamber.

By then, Wood and her partners had sold the firm, nearly bankrupted by its rapid expansion across the nation and in several other countries. As it changed hands several more times over the next decades, Wood remained a consultant, defending her method against mounting attacks from scientific investigators, who found that Wood-trained readers were merely skimming, at disastrous cost to comprehension. As enrollment hit half a million, a growing number of customers asked for refunds but found them hard to get. Providing the veneer of legitimacy, kinescopes of the ABC show featuring the senators were shown for years at Evelyn Wood sales sessions.

Even as all four of Wood’s senatorial fans stayed in office, the testimonials shrank to one. Eventually only Proxmire’s face appeared in ads, next to his assessment of his Evelyn Wood course: “I must say that this is one of the most useful education experiences I have ever had. It certainly compares favorably with the experiences I’ve had at Yale and Harvard.” A decade after he first said that, he was questioned about it by the Federal Trade Commission. He said those were his words, adding that he’d received no money for them, an explanation that appeared to satisfy the FTC.

Republicans, meanwhile, had re-entered the game. In 1970, the Nixon White House quietly contracted Evelyn Wood instructors to school its White House staffers. Among the pupils were press secretary Ronald L. Ziegler and speech writer Patrick J. Buchanan. But by then the Evelyn Wood marketing machine was sputtering, and the media barely took notice. Anti-war protests had darkened the mood on college campuses, a main source of Evelyn Wood revenue. Bright-eyed demonstrators began encountering hecklers instead of applause. At the University of Washington in Seattle, frustrated refund-seekers formed a group called Students Against Evelyn Wood.

Hope revived when Carter arrived in the White House, arranging Evelyn Wood classes for himself, some family members, and about fifteen others. According to Carter, eight weeks of instruction with an Evelyn Wood franchise owner had him reading 1,000 words per minute, just below the pace attributed to Kennedy. Presidential enthusiasm gave the business a lift, just as its fourth set of owners were preparing to sell it.

But the resuscitation wasn’t entirely successful. News outlets that had once boosted the Evelyn Wood method now derided it, soliciting quotes from skeptics long ignored or dismissed. The adulatory headlines of 1961, like, “She Can Teach You to Read 2,500 Words a Minute!” were displaced in 1982 by “Sp’d Read’ng or Skimm’ng?” While never regaining its past popularity, the brand survived its creator’s 1995 death. Evelyn Wood books and courses are still sold. The name means little to millennials, but a new crop of competitors is angling for them, marketing apps and display technologies that promise to turbocharge reading speeds.

This time, however, the speed merchants can no longer expect a boost from Washington, at least, not from Democrats. Among Trump’s opponents, slow reading, like slow food, has regained popularity. With podcasts and round-robin readings, progressives encourage the savoring of every word. As for the other side, MSNBC legal analyst Mimi Rocah tweeted, “Every single @Senate GOP @HouseGOP member who appears on TV to defend Trump should be asked if they’ve read the full Mueller Report & for specific examples so they can’t fake it.” Evelyn Wood’s debunkers couldn’t have phrased it better.

©Marcia Biederman, 2019

July 7, 2019

A new play about Patricia!

I’m delighted to report that I’m not the only writer fascinated by Patricia Murphy. A theater group based in her Canadian hometown will be presenting an original one-act, Opening Night at the Candlelight, on four nights in July and August 2019. The play begins just weeks after the 1929 stock market crash. Young Patricia has decided to sink her last sixty dollars into a failed Brooklyn Heights eatery.

Written by Constance Newhook, the play imagines Patricia making calls to a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle. That is certainly pure Patricia! She never made a move without looking for publicity. It will be presented in Placentia, Newfoundland, the small but wonderful place where Patricia’s life began. I treasure my memories of my all-too-brief visit to Placentia when I was researching my book. The people there couldn’t have been more encouraging and generous.

The publicity photos for the play look wonderful. More information is here.

Patricia Murphy comes alive again in a new play.

Patricia Murphy comes alive again in a new play.

January 31, 2019

Patricia’s DNA lives on at the Milleridge Inn

Patricia Murphy’s legacy lives on! A friend of mine proved this by dining at the Milleridge Inn in Jericho, Long Island, and sending me this photo of her server. Patricia had no direct connection with the Milleridge, but until recently, it was owned by two generations of her family members. These other Murphys borrowed many ideas that made Patricia Murphy Candlelight restaurants legendary for four decades — good food, lovely décor, and popovers.

Milleridge

Inn server Amanda Adamo, pictured in the photo, is proud of her role in

culinary history. Contacted by this author, she wrote, “We like to keep the traditions still going. All of our popovers

are fresh. They are made with eggs, butter and milk. A lot of people that come

to the restaurant to receive a popover because it is uncommon now. It is fun to

serve something that is so historic.”

Patricia Murphy made popovers her signature item because people weren’t likely to make them at home. The ingredients were relatively cheap during the Great Depression, when Patricia started her business on a shoestring. By 1954, she’d opened three restaurants and earned millions, partly because people kept coming for the popovers. On her wrist was a bracelet with a popover charm.

Like Patricia’s long-gone suburban restaurants, the Milleridge is vast, with private rooms for parties and little shops surrounding it. But although Patricia’s DNA pulses through this charming restaurant, she was estranged from the brothers and sisters who once owned it.

As I recount in my book, Patricia had planned to be the only Murphy operating a Long Island restaurant. As the eldest of seven siblings who’d fallen on hard times in their native Newfoundland, she went to New York alone. Once she’d found success in Brooklyn, she brought her entire family to the US. In return, her brothers and sisters helped out in her city eateries. Branching out to Manhasset, Long Island, in 1950, Patricia planned to continue employing them. But the sibs wanted their own slices of postwar prosperity.

Led by James, the eldest brother, they hatched a secret plot to start their own restaurant. Jim convinced the others to buy a restaurant in Great Neck — a short hop away from Patricia’s Manhasset place — and name it Lauraine Murphy’s. They copied her format and menu — right down to the popovers. Their ads even proclaimed Lauraine Murphy’s to be “the home of the popover.” Patricia never spoke to them again.

Incensed, Patricia left Long Island (a step she later regretted.) By 1954, she’d sold all three of her initial restaurants, allowing the new owners to use her valuable name. That gave her the million she needed for her ten-acre flagship in Yonkers. From there, she expanded into Southern Florida, eventually returning to Manhattan to open three more Candlelights.

In the meantime, James

Murphy, with the assistance of the other mutinous siblings, became a successful

restaurateur in his own right. In 1964, he bought and restored the Milleridge

Inn, parts of which date from 1672. The Lauraine Murphy restaurant was sold to

finance the purchase; lesss adventurous than Patricia, James took only

calculated risks. The Milleridge was a hit — in the Seventies, its bar drew singles

employed by Long Island’s emerging tech industry — and Patricia’s siblings

were set for life.

In recent years, Murphy

family members decided to sell the Milleridge, and residents feared it would be

razed. On a Facebook page called Save the Milleridge, people shared memories

and organized resistance. Fortunately, a restaurant company stepped in,

introducing new ideas while commemorating the restaurant’s heritage. I salute

them for commemorating Patricia in every popover.

December 4, 2018

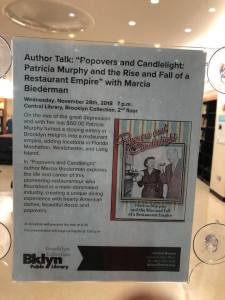

Please share your memories of Patricia Murphy’s restaurants

I was delighted to discover that many of the audience members at my recent Brooklyn Public Library author talk had vivid and detailed memories of their visits to the Patricia Murphy’s Candlelight restaurant in Yonkers, NY, even though they were quite young at the time. (Most had no idea that Patricia Murphy had eight other restaurants.) Years ago there was a discussion thread on roadfood.com where customers and employees of various Patricia Murphy’s sites posed their reminiscences. Here’s one you may enjoy (see also my blog post about Patricia’s line of fragrances):

Does anyone remember Patricia Murphy’s Orchid Carousel in the 1958 International Flower Show in the New York City Coliseum and me–representing her White Orchid Perfume–riding on it? If someone can tell me how to add photos, I can add two from Patricia Murphy’s Yonkers restaurant lobby, and one from the New York City Flower Show…

and another:

As a young person, in the early 50’s, I really liked Patricia Murphy’s Candlelight Restaurant. They served a good American menu. Everything from soup to desert was included in their base price. They also gave an option of a cream de menthe or a crème de cocoa in lieu of desert. I liked that very much as I grew old enough to partake, because I was usually too full of those fantastic popovers to even look at desert.

If YOU or anyone you know has any memory you’d like to share, please contact me through this site or shoot me an email: marcia@marciabiederman.com, and I’ll post it on this page.

Meeting audience members at the Brooklyn Public Library. So happy to hear their memories!

November 11, 2018

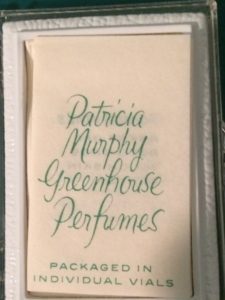

Taking home a whiff of the restaurant experience: Patricia Murphy Greenhouse Perfumes

By the late 1950s, Patricia Murphy was famous in New York City, Long Island, Westchester County, and Fort Lauderdale, FL, for her restaurants and gardens. She decided to extend her brand into a line of fragrances. Like everything else that Patricia touched, her line of scents was an instant hit.

By the late 1950s, Patricia Murphy was famous in New York City, Long Island, Westchester County, and Fort Lauderdale, FL, for her restaurants and gardens. She decided to extend her brand into a line of fragrances. Like everything else that Patricia touched, her line of scents was an instant hit.

Long waits for tables were part of the dining experience at Patricia Murphy’s Candlelight Restaurants. They were also a strategy for selling. State-of-the-art public-address systems eliminated the need to stand in line. At her city restaurants, patrons could while away the time at the bar, and at her suburban locations they could stroll through her expansive award-winning gardens.

Better yet (for the balance sheet) customers could shop at the gift shops attached to the Candlelights for Patricia Murphy-branded perfumes, colognes, and bath oils — a lasting memory of the day.

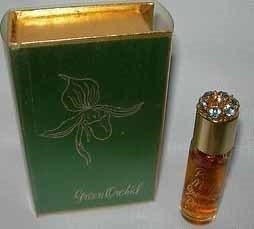

Patricia’s first fragrance, Green Orchid, was a blend of floral scents, described as having  “woodsy and woody notes, a whiff of amber, and a pinch of spice.” In 1961 a jewel-top bottle of the perfume sold for three dollars — more than the price of a dinner — but was also available in individual vials. Even budget-minded customers could splurge on a single orchid, available at the greenhouse, and a few vials of Green Orchid perfume.

“woodsy and woody notes, a whiff of amber, and a pinch of spice.” In 1961 a jewel-top bottle of the perfume sold for three dollars — more than the price of a dinner — but was also available in individual vials. Even budget-minded customers could splurge on a single orchid, available at the greenhouse, and a few vials of Green Orchid perfume.

The fragrances were based on Swiss essential oils. At this point in her career, Patricia made sure that anything bearing her name lived up to her standards. She visited the Geneva manufacturer during her gift-shop buying trips to Europe or after watching her racehorse, Treaty Stone, compete in Ireland.

Another fragrance, Gold Orchid, was added. A third, Regina Rose, was unveiled at an International Flower Show at the New York Coliseum, where Patricia’s orchids took top prizes. Soon the Candlelight gift shops were hiring specialized perfume salespeople and filling mail orders. Vats of the stuff were sold and are still regularly offered on ebay.

July 8, 2018

More Than Candles: Patricia Murphy was a Lighting Innovator

Below is a photo of one of the many dining rooms at Patricia Murphy’s Candlelight restaurant in Manhasset (Long Island) NY. In addition to the candles lit at all of Patricia’s restaurants, even at lunchtime, there was also exquisite electrical lighting. It was designed by Richard Kelly, who later lit Manhattan’s Seagram building and its famed Four Seasons restaurant. Kelly listed his collaborations with Patricia among the top projects on his resume, along with his work at Lincoln Center.

Patricia and the architect of her two suburban New York restaurants, Nathalie Rahv, encouraged Kelly to experiment with dimmers, a novelty at the time, uplights and downlights. Approaching the dining rooms as if they were museums, Kelly artfully drew attention to architectural features, like the towering fireplace in Manhasset, flattered the faces of restaurant patrons, and highlighted floral displays both inside the dining rooms and outside in the gardens. A Yale-trained architect as well as a lighting expert, Kelly had worked in theater. At Patricia Murphy’s Candlelight Restaurants, he set the stage for memorable dining experiences.

So remarkable was the lighting at Patricia’s eateries that General Electric ran two features about it in Light, its magazine for interior designers and lighting professionals.