Marcia Biederman's Blog, page 4

April 28, 2021

The WW2 Homefront of “A Mighty Force”: Lessons for the Pandemic

As states rush to list all restrictions aimed at slowing the spread of Covid-19, many of us wonder how we got here. How can Americans place the nation at risk to pursue their personal goals? In fact, we’ve been here before, as I learned from researching my forthcoming book, A Mighty Force. A year before V-J Day, the homefront seemed headed for collapse as thousands of Americans ditched war work to seek jobs in sales and marketing.

Reacting to this threat, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration identified “essential workers”—including civilian physicians, like Dr. Elizabeth Hayes, the subject of my book—and froze them to their jobs. Their employers had to give them release forms before they could seek other work. Also affected were the 350 coal miners who went on strike to support Hayes’s battle for clean drinking water in their company-owned town. They’d long been at the mercy of the mining company that hired them and owned their housing. The job freeze made things worse.

The federal government took this unusual step to counter widespread “peace jitters.” Acting Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson, coined the term in July 1944, when a widespread belief that World War II was “all but over” had left war industries with a shortage of 200,000 workers, threatening the flow of supplies and endangering lives.[1] Many Americans felt certain that Germany would fold any day now, taking munitions-plant jobs with it and leaving them adrift in the postwar future.

The homefront of Hollywood films—full of victory gardens, metal-scavenging kids, riveting Rosies, and cheerful shipyard workers—had largely evaporated by this point. A huge chunk of the Greatest Generation was prematurely ready to bail.

Presaging our varying views on the virus, many Americans underestimated the peril of leaving troops underequipped. Trying to stop the hemorrhaging, the war department filmed grim scenes of soldiers pleading for war material and screened them to millions of workers. Still, the exodus continued, perhaps because “unless you actually have seen the war you can’t grasp what they are driving at,” as some department officials suggested.

D-Day and the liberation of Paris had much the same effect as Covid vaccinations and recent dips in deaths and cases. “Our problems are created by our successes. Too many people think that we are ‘over the hump’ and that they may now let up in their war efforts,” said Paul V. McNutt, chairman of the War Manpower Commission, sounding like a prototype of Dr. Anthony Fauci. [2]

Then, as now, there was plenty of finger-pointing and charges of misinformation. Journalists said that the war department must have been hiding something if they felt that the war was going to continue much longer. The department, in turn, accused radio and newspaper outlets of “making every small step toward victory appear to be a major triumph.”[3] Wishful thinking also played a part. For some Americans, the attempted assassination of Hitler and changes in the Japanese war command signaled an imminent end to the conflict.

Corporations were charged, as they would be again, with placing profits over people. As orders from the military ebbed, manufacturers eager to re-enter the consumer market talked of making drastic layoffs. Panicked workers raced off to compete for peacetime jobs.[4]

In Force, PA, the setting of my book, Dr. Hayes and her miner allies took the job freeze seriously. Elsewhere, however, government attempts to freeze workers to “essential” war work were mostly futile. In July 1944, the United States Employment Service was assigned to oversee all hiring of males and, in some places, females, or at least those women working in “critical industries.” People weren’t supposed to quit war jobs without a signed release to show their next employers.[5]

But, as with mandates and capacity limits, the rule was widely flouted. In a warning for any proposals for vaccination passports, counterfeit job-release forms were soon available for a dime. Many employers didn’t demand the releases anyway, despite the government’s urgings.[6]

Dropping our guard didn’t change the outcome of World War II, but it may have cost lives. By November 1944, munition stockpiles had dwindled, pontoons used in bridge-building were growing scarce, and certain shells had to be hurriedly flown to a battle zone and rationed when they arrived.[7] Still ahead were months of fierce fighting, including the Battle of the Bulge in Europe and the Battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa in the Pacific.

In New Jersey, where 50,000 had left war plants, job recruiter William J. Orchard said, “Too many people are indulging in the very human characteristic of . . .wanting to do everything that seems necessary to win the war, but not being willing to knuckle down.”[8] Before flinging our masks in the trash, we should mark those words.

And for more about the WW2 homefront we never really knew about, get a copy of A Mighty Force, available now for pre-order through Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.

[1] Sidney Shallet, “War Chiefs Warn of Peace Jitters,” New York Times, Jul 21, 1944.

[2] “McNutt Asks Staff to Be ‘Supersalesmen’ In Persuading War Workers to Stay on Job,” New York Times, July 27, 1944.

[3] NWNS, “This Week in Washington,” Harlan County (Alma, NE) Journal, Aug 3, 1944.

[4] Todd Wright, “Peace Jitters Peril Nation’s War Effort, Daily News (New York, NY), Dec 10, 1944.

[5] Louis Stark, “Manpower Curb Put Into Effect to Get War Labor,” New York Times, Jul 1, 1944.

[6] Wright, Ibid.

[7] “USES Head Urges Workers to Keep Defense Jobs,” Morning Call (Allentown, PA), Nov 29, 1944.

[8] “’V-E Jitters’ Are Menace to Labor,” Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick, NJ), Dec 1, 1944.

March 31, 2021

BBC Radio 4 interviews me about Evelyn Wood and Scan Artist

BBC radio host and best-selling author Matthew Syed interviewed me about Evelyn Wood for an episode of his program, “Sideways.” The segment about Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics begins at point 06:45 of the episode, as we travel back to 1961 to the set of the TV game show, “I’ve Got a Secret.”

I’m excited and honored to be part of a BBC show. Incidentally, Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics opened a branch in London, but it never really took off. At 55 guineas (more than $1,000 today) for eight three-hour lessons, the price struck the Times Literary Supplement as “prohibitive,”, particularly for students. Characteristically, Evelyn Wood responded, “When people want something, they get it.”

In the end, the UK branch of Evelyn Wood had to peddle its wares to Americans instead, selling courses on British history and English culture and literature. To their credit, the British public wasn’t sold on speed-reading, at least not at the prices quoted.

March 8, 2021

Parallels with the Paranormal: speed-reading & psychics

I was amazed to hear an insightful discussion of my book SCAN ARTIST: HOW EVELYN WOOD CONVINCED THE WORLD THAT SPEED-READING WORKED on a podcast largely devoted to game design! My thanks to game designers and authors Kenneth Hite and Robin D. Laws, who dedicated a portion of their Feb. 19, 2021, podcast to an entertaining and fast-moving summation of my book’s main points. As they noted, there was a “mystical tinge” to Evelyn Wood’s pseudoscience.

The podcast is here. The segment about SCAN ARTIST starts about forty-five minutes in, or at counter 45:00. The preceding discussions of roleplaying games and films are also worth a listen.

Indeed, there are striking similarities between the belief in speed-reading and the belief in mystical experiences or the paranormal. Interviewed about the experience of speed-reading nonfiction, Wood told of the “breakthrough” moment when she ceased reading the words of a novel as mere text. Instead, Wood said, she found herself walking in the Venezuelan rain forest described in the book, experiencing the sights and sounds as if in a movie. In the early 1960s, students in Evelyn Wood “institutes” were encouraged to strive for similar moments. Speed-reading a book about the Chicago fire, one young student shouted out, “I’m on fire,” much to satisfaction of the instructor, as well as the company. A journalist who was present reported this without a whiff of skepticism.

It is amazing that Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics classes were organized in both chambers of the US Congress and that a host of senators, most of them Democrats, endorsed this hoax for decades—as did Fortune 500 companies, including Boeing. As the podcast mentions, it’s no coincidence that Wood’s entrance into Washington DC in 1959 was first noted by a mimeographed newsletter, “The Little Listening Post,” which also reported flying-saucer sightings.

My favorite quote from the podcast: “It’s a great social history as well as a history of this particular all-American scam.”

February 3, 2021

Agreeing to disagree: German Speed-Reading Society Welcomes Me!

I was honored to be a featured speaker at a recent Zoom meeting of the German Society for Speed-Reading. The group’s chair, Peter Rösler, knows my book, Scan Artist, and was well aware that I don’t believe that speed-reading is possible without a sharp drop in comprehension. Nevertheless, he felt that his group and I share enough common interests to have a productive discussion. As it turned out, we did.

The group was particularly interested in hearing about my two trips to view the Evelyn Nielsen Wood Papers at the Utah Historical Society in Salt Lake City, where Wood spent most of her life. I described the many boxes of personal and business documents that are archived there. I was particularly gratified that one member of the society—a woman—had been interested in my account of Evelyn’s life. Whatever you think about speed-reading, the biographical portion of my book is the story of a woman who overcame gender barriers to make a huge impact on popular culture and business history.

The German society includes members from other European countries, including Poland. They were surprised to learn that speed-reading had become such a craze in the US. Asked about this, I discussed the “influencer” factor. Unpaid and (sometimes) unsolicited endorsements from prominent politicians and celebrities were tremendously important in promoting the Evelyn Wood method.

Above all, though, Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics Inc. exploited the insecurities of the moment. Economic prosperity and the explosion of white-collar job were sending legions of first-generation (mostly white) students to college, where they felt unprepared for the reading load. At the same time, the Cold War was on, and a slew of articles appeared with titles like, “Why Johnny Can’t Read, and Ivan Can.”

I thank the German Society for Speed-Reading for their broadmindedness in inviting me. As I told them, I doubt that an equivalent American society would do the same.

And we’re still exchanging research materials!

November 6, 2020

I, the author, look back at my role in systemic racism.

Many thanks to the CTMirror, an online publication that ran my recent opinion piece, “That Little Girl Was a Future State Senator, and I Ignored Her.” An update: Connecticut State Senator Marilyn Moore, the subject of my piece, has won election to a fourth consecutive term. She deserves more national attention, having overcome obstacles placed in her way by me as well as others.

June 29, 2020

No Justice for Capatoria Epps: My op-ed piece about the historical failure of the criminal justice system

About a year ago I became aware of the brutal 1952 murder of Capatoria Epps, a young Black New Yorker, and the racism that shielded her white killer from punishment commensurate with the crime. I thank the New York Daily News for recognizing that her life and death must be remembered.

April 15, 2020

Tune in to my Facebook Live author talk

I’ll be doing a virtual author talk for the Westport Museum for History & Culture on Friday, April 17, 2020. Please tune in from 5-5:30 Eastern Time at https://www.facebook.com/events/2714324242124800/ Evelyn had a special connection to Westport, Connecticut, an idyllic shoreline town, where Wall Street types live side-by-side with artists and writers. Westport was once home to the Famous Artists Schools, Inc., which acquired Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics in 1967 for about $4 million, retaining Evelyn as a consultant. Find out how she and her husband, Doug — devout teetotaling Mormons — handled themselves at Westport’s cocktail parties of the swinging Sixties.

February 16, 2020

Proud to be singled out for failure (Failure Magazine, that is!)

My book Scan Artist is featured in the latest edition of Failure Magazine, an online publication dedicated to exploring “humankind’s boldest missteps.” Evelyn Wood’s fraudulent speed-reading method certainly falls into this category, Be sure to check out my Q&A with Failure Mag’s Jason Zasky about the people who propelled Wood to international fame, as well as the debunkers who stalked her from the start but were unable to gain traction.

We also discussed why Americans of the era, including notable political figures, so desperately wanted to believe that Wood could teach anyone to read 2,000 words per minute without losing one iota of comprehension. We also talked about the psychological insecurities of those times, on which the Wood system preyed.

I’m glad to be in good company in Failure, which regularly reviews books and writes features about noble failures as well as scams in sports, business, government, and history. You might also enjoy the review of a memoir, Sounds Like Titanic, by “fake violinist” Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman about a concert tour in which barely-qualified musicians performed with microphones off while music recorded by professionals played — the instrumental equivalent of lip-syncing. It was a low-cost promotional gimmick cooked up by a composer, whom, probably for legal reasons, Hindman declines to name.

In my own bit of self-promotion, allow me to note that the Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics, unlike many other scams, became part of the fabric of American life for two decades — facilitated by the uncritical adulation of nearly all major US media outlets, and endorsed by senators and presidents.

January 13, 2020

Kindle’s Down-to-Earth Estimates of Reading Speed

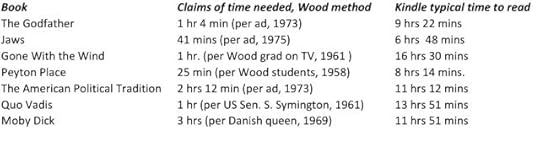

In contrast to this preposterous claim, Kindle’s Typical-Time-to-Read Estimate for The Godfather is 9 hours and 22 minutes

In contrast to this preposterous claim, Kindle’s Typical-Time-to-Read Estimate for The Godfather is 9 hours and 22 minutes Speed-reading scams still pop up regularly on the internet, and graduates of Evelyn Wood courses often protest, in print or in person, when I call her method a fraud. Still, almost no one believes in speed-reading anymore. Proof of this can be found in Amazon’s “typical to time” to read measures, available for millions of books published in Kindle editions.

Planning to read Where the Crawdads Sing on a Kindle? Amazon estimates it will take you 7 hours and 35 minutes. How about Michelle Obama’s Becoming? Expect to set aside 8 hours and 34 minutes. Or would you rather curl up with The Trump-Ukraine Impeachment Inquiry by the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence? Prepare to block out 7 hours and 50 minutes.

In each case, Amazon appears to assume that readers, or at least “typical” ones, proceed through text at around 250 words per minute. (Your own time may vary, and Amazon has an algorithm for that, as I’ll explain later. For now, let’s focus on its typical reading times, which were identical for me and other Kindle users I consulted.)

Here’s how I converted the typical-time-to-read figures into words per minute. The number of words on a printed page can, of course, vary. But I know the exact word counts for my own books, so I can see that Kindle “pages” consist of 275-300 words. Hence, if it takes the typical reader 4 hours and 48 minutes to read the Kindle edition of my 240-page (i.e. 72,000-word) work, the typical reading speed is 1.2 pages or slightly more than 300 wpm.

Thank you, Amazon! It’s been known for decades that this is the average adult’s reading speed. Given the limitations of eye anatomy and the time required to process words into meaning, “college-educated adults who are considered good readers usually move along at about 200 to 400 wpm,” according to a 2016 study co-authored by University of South Florida professor Elizabeth R. Schotter, which found little evidence that people can learn to speed-read without sacrificing comprehension.

“Whoever claims to be a speed-reader is likely skimming,” Schotter has said, adding that Evelyn Wood’s claims were “crazy, based on the scientific evidence on reading.”

Eric Spitznagel, “How a Mormon Housewife Sold America the Big Speed-Reading Scam,” New York Post, Sep. 21, 2019

Yet those who read at normal rates are still easy marks for fraudsters. The shaming is powerful — and shameful. “It’s No Longer a 250-Word-Per-Minute World,” warned the headline of a 1967 Newsweek wire service story that ran in scores of newspapers. A decade earlier – even before Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics opened its first Washington institute – a Purdue University reading “expert” declared that those reading under 500 wpm were “handicapped” in the business world.

Nonetheless, here we are in 2020, still reading the way Evelyn Wood promised to disrupt with her “reading revolution” and somehow coping. But many people are still insecure about their reading speeds, while others delude themselves that skimming is reading. Another Kindle setting, the time “left in book” – or “left in chapter” if you prefer fine-tuning – can exacerbate the problem.

Consider my own case. With two days left before a meeting of my book club, I’m only a few chapters into Sonia Purcell’s excellent book, A Woman of No Importance. Consulting the menu at the top of my Kindle screen for information about the book, I find that the typical time to read this book – 368 pages – is 9 hours and 34 minutes. But because I’ve activated “time left in book” in my display settings, I can see that one of Amazon’s mysterious algorithms has me marked as a faster-than-average reader. As I start the book, I see at the foot of the screen that my time left is 5 hours and 1 minute. Yes, Amazon has it worked out to the minute.

Hence, according to Amazon’s secret sauce, I can polish this particular book off at about 370 wpm. Yet the typical time to read, found in the About This Book menu, works out to 192 wpm. That unusually slow “typical” rate might be based on the difficulty of the book. Purnell did a staggering amount of research, and the text is unusually dense with information.

According to Amazon, the “time left” algorithm takes a number of factors into consideration, including the type of book and words per page, as well as your own previous reading sessions. I’m not sure how “words per page” factors in, since the user can choose how to display the font, but I suppose it has to do with page turning, which done digitally, is a rapid operation.

As for the type of book, it’s arguable that Purnell’s book is more challenging than many. However, Amazon’s typical-time-to-read figures suggest that my own university press book, Popovers and Candlelight: Patricia Murphy and the Rise and Fall of a Restaurant Empire, is a tougher slog than Scan Artist. They are about the same length in their Kindle editions, yet Amazon thinks Popovers takes the typical reader about two hours longer to finish. As the author, I can confidently state that this is untrue. Academic publishing does not necessarily indicate academic language.

But let’s go back to my book-club deadline. As I progressed through A Woman of No Importance, I must have quickly fallen short of Amazon’s expectations. The part of their algorithm based on my previous reading might have been skewed by my secret vice: Catherine Cookson novels. I love Cookson for recreational reading, but though meant for adults, her books are on the YA level. Many are part of a series, in which the beginning of each book is the recap of the previous one, allowing me to read them relatively quickly – though never approaching the rates claimed by self-described speed-readers.

As I plodded through Purnell’s absorbing but challenging text, my Kindle seemed to sense that I was failing to achieve my Cookson speed. The “time left” in the toolbar barely budged. I felt as though I were driving with GPS on, repeatedly making wrong turns and causing recalibration. With my Kindle warning me that I had more than an hour left in the book – a prophecy that proved true – I left for my meeting and came clean with my clubmates. I hadn’t finished it.

Would that slow-moving read-o-meter have helped me with college all-nighters? No, I found it crazy-making. It might have made me more susceptible to offers of amphetamines, or to the false promises of speed-read scams.

So leave that personalized “time left” setting off. No one enjoys reading against a clock. But take heart from the typical times to read, which Amazon doesn’t use as a selling point. Lots of other information about the book, the number of pages, and the author can be accessed on its website, but a book, or at least a sample, must be downloaded to access its “typical” time.

If you’ve already got some downloads, take a look at the typical stats. Remember, this measure has nothing to do with you, or even with rates clocked on other people’s Kindles. (Again, speeds stored in your Kindle stay in your Kindle.) From the first day of my books’ releases, their typical times were available. Obviously, they’re based on the human-scale average rates, agreed on by researchers before and after Evelyn Wood. Contrasting them with claims made by Evelyn Wood and her followers, we find:

We could put a man on the moon, but . . .

We could put a man on the moon, but . . .

We’ve come a long way from self-delusion — or at least some of us have. Reading, which involves thinking, takes time. May you and I resolve to leave sufficient time to prepare for our classes, law cases, presentations, and book clubs. We’re only mortal, Evelyn.

December 16, 2019

In newest speed-reading scam, popular in China, no need to look at the pages

From Quantum Speed-Reading by Yumiko Tobitani

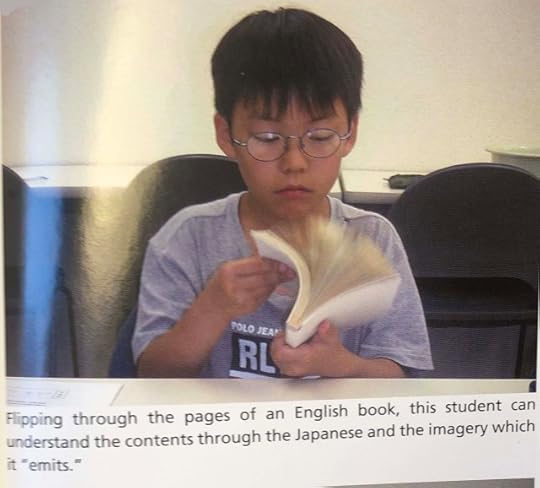

From Quantum Speed-Reading by Yumiko TobitaniEven at her most preposterous, Evelyn Wood never claimed that her students could read books without even glancing at the pages. Her finger-pacing system required students to trace lines down text, as fast as they could turn the pages. But a new craze called Quantum Speed-Reading takes the old Wood claims to the next level, insisting it can teach kids to read books by simply flipping pages.

This latest speed-reading nonsense is attracting wide attention in China, where a video of a reading competition went viral in October, quickly attracting 140 million views. The children in the video, aged six to twelve, were said to have studied the Quantum Speed-Reading, or QSR, method, which purports to teach students to read 100,000 characters in about five minutes.

That’s a rate claimed by only the most fervent devotees of Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics. (Most college-educated adults read between 200 and 400 wpm.) As I wrote in my book, Scan Artist, Senator William Proxmire of Wisconsin said he could read 20,000 wpm after taking a Wood course in 1961. But the Wood method made him move his finger down text before turning pages. QSR kids just flip through a volume, like shuffling cards.

QSR earned a fresh burst of attention from the video, but it’s been around for more than a decade. The system is based on the work of a Japanese woman, Yumiko Tobitani, whose 2006 book, Quantum Speed-Reading: Awakening Your Child’s Mind, was translated into English and released in the US by Hampton Roads Publishing. The book appears to be out-of-print – orders through Amazon cost triple its original $14.95 price– but I was able to see a copy in a library.

Like Evelyn Wood, Tobitani presented no scientific evidence for her method, relying instead on testimonials from satisfied students. In the case of QSR, these endorsements come from children. One second-grader reported flipping through Stephen Hawking’s The Universe in a Nutshell and sending Dr. Hawking a letter to tell him that he’d “overlooked something.” The child said he’d comprehended the book by receiving “good images” from it “like having an antenna on my head.”

As with Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics, preposterous claims are cloaked in scientific-sounding jargon. Tobitani described herself as a teacher at the Shichida Child Academy in Japan, where great emphasis was placed on “activating the right brain” so that children flipping through a book would be “picking up the thought vibrations emanating from it,” somehow translating these into understandable information. According to Tobitani, the child need not understand the language of the text in order to understand it.

Speed-reading never has come cheap.

An Evelyn Wood course, adjusted for inflation, always cost at least one

thousand dollars. QSR, taught at training centers in Beijing, Hangzhou and

Shenzhen and elsewhere in China, can range from 6,000 yuan ($860) for a

half-year of training to 260,000 yuan ($37,000) for lifetime enrollment.

Modern-day Asia has been far more skeptical of these outlandish speed-reading claims than mid-century America ever was. While debunkers of Evelyn Wood’s method were largely ignored by the US media from the early 1960s until the late Seventies, the recent QSR video has sparked a dozen critical media reports. China Daily and the South China Morning Post, among other outlets, have run comments from scientists and education experts calling the Quantum Reading method “nonsense” and “groundless.”

To be sure, the circumstances are not comparable. Evelyn Wood’s method was endorsed by political figures and celebrities, while authorities in Sichuan province are said to have taken a dim view of the QSR video. According to the South China Morning Post, “cyber police” shared the competition video on the social media site Weibo with the comment, “New scam?”

A report about the flap on Jiemian.com, a Chinese website about business and finance, links to a New York Post story about my book, Scan Artist. It’s heartening to know that my own work has been noticed in China and that skeptics are on the case.