Christine Valters Paintner's Blog, page 74

November 23, 2019

Monk in the World: Community 6 – Reflection Questions and Blessing ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

During this Jubilee year of sabbatical we are revisiting our Monk Manifesto by moving slowly through the Monk in the World retreat materials together every Sunday. Each week will offer new reflections on the theme and every six weeks will introduce a new principle.

Principle Three: I commit to cultivating community by finding kindred spirits along the path, soul friends with whom I can share my deepest longings, and mentors who can offer guidance and wisdom for the journey.

Questions for Reflection

Where in your life do you experience a genuine sense of community or soul friendship already?

When you slow down and listen to your longings for spiritual companionship, what are some of the qualities which rise up as essential?

Closing Blessing from Christine

God of friendship

we come to know you through the

grace of one another.

Weave us together with kindred spirits,

knit us more closely with friends of the soul,

gather us into your great wide heart,

so we might discover the One in many,

and the many in One.

With great and growing love,

Christine

Christine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

Photo © Christine Valters Paintner

November 21, 2019

Christine's Recent Poetry + Art

Christine has had several poems published recently in various journals online:

Christine has had several poems published recently in various journals online:

Book of Kells in ARTS: Journal for the Arts in Religious and Theological Studies

Handless Maiden in North West Words (inspired by one of Christine's favorite fairy tales of the same name)

Little Red Riding Hood in Bangor Literary Journal

Christine has a second collection of poems that will be published in fall 2020 by Paraclete Press titled The Wisdom of Wild Grace with a series of poems inspired by the many wonderful stories of kinship between saints and animals. She's been working with UK artist David Hollington to illustrate some of these in his marvelous folk art style. Here is the next artwork in the series accompanied by the poem that inspired it.

St. Julian and the Cat

Stone by stone the wall grew

until her cell was sealed,

light blocked except for

three small windows –

one for sacrament

another, food and waste

a third to give guidance.

Each day brought dozens to her

praying for their sick and dead,

night became time of solace

and silence, she could not

sleep long in the damp,

pulled wool close around her

as she sighed into the dark,

relief at quiet moments.

Then came mewing,

leaping, pouncing, the cat

left there to catch rats,

at first annoyed at disruption

she soon found wisdom

in his aim and purpose,

grace in his hours of stillness,

how she too was there to hunt

the holy, and rest into being.

Morning prayers became

a mix of chants and purrs

as warm fur nestles into her lap.

Visitors arrive again

to her window, she gives

her most sage advice:

allow yourself to be comforted,

do not be afraid of the night,

and pursue what you long for

with a love that is fierce.

—Christine Valters Paintner

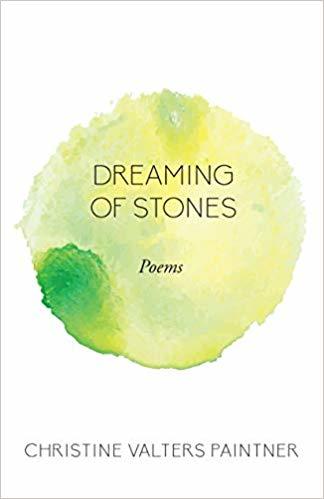

Dreaming of Stones: Poems Review

So grateful to Linda Susan Courage of Living Spirituality Connections UK for her lovely review of my poetry collection:

So grateful to Linda Susan Courage of Living Spirituality Connections UK for her lovely review of my poetry collection:

***

Christine takes us into ordinary, familiar places and opens them in extraordinary ways. Nature, emotions, news, feelings, time, places, artefacts are woven with longings, humour, gentleness, and possibilities.

Readers might be laid bare by their reading, but not cast adrift. We are taken into stories and on journeys that are strangely familiar. The collection might be summarised by her own words in her poem, 'Little Hours'

Attention illuminates corners of the world,

this is the honorarium of the ordinary.

I have many favourites, and lines that will stay with me. 'St Francis at the corner pub' delights with his flash of polka-dotted boxers; 'Ancestral Time' knows with its breathing and long ache inside us; 'An Unquiet Revolution' ends with 'you just might believe/that anything at all is possible.'

I think the collection deserves a wide readership; it speaks to the breadth and depth of life in nourishing, unsentimental ways.

***

You can read all of Linda's review at this link along with many other wonderful spirituality and creativity resources for those living in the UK.

November 19, 2019

Featured Poet: Bethany Reid

Last spring we launched a series with poets whose work we love and want to feature and will continue it moving forward.

Our next poet is Bethany Reid whose work is centered on memory, caregiving, loss and wings. Read her poetry and discover more about the connections she makes between poetry and the sacred. Listen to her read "Sparrow" below.

https://abbeyofthearts.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Sparrow-voice-recording-1.mp3

Sparrow

What could the Bible mean

when it says no sparrow falls

without God's notice?

They do fall.

"The Bible": that's too impersonal.

It was some writer of the New Testament,

some Hebrew poet turned Christian

who chose "sparrow," a metaphor

for the least things, the small

and innumerable mouths

at the breast of the world.

Maybe our poet had a daughter who carried to him

in her cupped hands a baby sparrow.

Maybe they tried to keep it alive

on sugar water and cat food,

and when they failed, he wept,

not knowing how to teach a child

that life is worth the trouble, and the grief.

This morning, at our house,

the sparrow hopped in his shoe box, chirping,

and my daughter leaned over him,

her hair the same brown as his feathers.

"He thinks I'm his mom," she told me.

I am her mom. When the sparrow dies

I'm the one she brings him to,

the life now seeped from him,

his body no more than a clod of dirt.

Black beads of his eyes dulled.

Wings stilled. Feet brittle as twigs.

We bury him in the backyard

beside the old cat and a mole we found last fall.

And why commending his body to the earth

should comfort us, God only knows.

Themes of Her Work

My father's unexpected death in 2010 and my mother's subsequent journey through Alzheimer's, a massive stroke in 2014, and her death in the fall of 2018 have immersed me in themes of memory and caregiving and loss. My mother's lost memories, my childhood memories of growing up on a farm (in the house my mother was born in) and in our Pentecostal church where my father served on the board and as Deacon – that's what I'm writing about now. Plus, a weird sub-theme of wings, which I can't seem to avoid.

Legs Thin as Branches

The muse when it is new

wobbles on legs thin as branches.

It bleats and mewls,

not a horse to be ridden,

only another baby

needing milk and love.

You have to believe in what isn't there

a long time before it begins

to be there. Years pass

before you dare put a saddle

on its back, before you dare

climb up and weigh the reins

in your hands. When it is new,

the muse teaches you

to practice faith in the music

of what you cannot hear,

to make art of what you cannot see.

When the day dawns

for you to trust your weight

to it, sit up straight. Gather all

that its long becoming

has brought forth in you.

Look steadily in the direction

you must go.

Poetry and the Sacred

Writing every day is an important part of my practice--something I managed even when my daughters were young. I consider writing in my journal (especially on the busiest days) to be as important to my well-being as brushing my teeth. But I have not always thought of writing as part of my spiritual practice. Writing a poem used to feel like a guilty pleasure, at best, and maybe like outright theft from "more important things." Then, a number of years ago, I was asked to lead a women's church retreat and, though the facilitator said it would be a cinch – I was terrified. I had been teaching writing and literature for at least a decade, but the thought of sharing my spiritual journey through poems, and inspiring participants to write poems about their own spiritual journey? That just didn't seem very likely. Luckily, I decided to talk the invitation over with my pastor. Secular teaching, I could do, I told him, but sacred? I really didn't think I was qualified. My pastor (a lovely man, with a gentle Irish brogue) said, "Oh, Bethany, don't you know? It's all sacred."

The retreat was great, by the way. No credit to me, but to the participants (mostly older women) who were so generous and kind. They wrote some really wonderful poems that day, and they inspired me.

Later I wrote down my pastor's words, "It's all sacred," and framed them. They used to sit beside my desk where I planned my classes and graded papers. Now that I'm retired from full-time teaching, they sit beside my writing desk, reminding me (of course I frequently need reminding) of not only why I write poetry, but why I do anything. It's all sacred.

I Could Love You That Way

The way a woman cleans house, tying her hair

in a kerchief, knocking down cobwebs

with a broom. All day gathering clothes

and toys and books from beneath the beds.

Vacuuming under the couch cushions,

scrubbing the drains, polishing

the fixtures. I could love you that way,

methodically, thoroughly, offering my body

at day's end as if it were a house,

as if it were a place for you to lie down.

The Soul Has Seasons

Like blackberry brambles the soul has seasons

when its leaves grow scarce.

Even then, a smallish body will find shelter there,

deer mouse chittering, or the tiny wren, piping its song.

For what, if not that singing, does the soul dare

a new season's greening?

About Bethany Reid

Bethany Reid's two most recent books are Sparrow, which won the 2012 Gell Poetry Prize, and Body My House (2018), published by Seattle's Goldfish Press. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals, including Blackbird, Broken Bridge Review, Cairn, Calyx, The MacGuffin, Pontoon, and Prairie Schooner, and are also included in the recent anthologies, For Love of Orcas and Footbridge Above the Falls: Poems by 48 Northwest Poets. Bethany lives and writes in Edmonds, Washington, and blogs about all of it at BethanyAReid.com.

Dreaming of Stones

Christine Valters Paintner's new collection of poems Dreaming of Stones has just been published by Paraclete Press.

The poems in Dreaming of Stones are about what endures: hope and desire, changing seasons, wild places, love, and the wisdom of mystics. Inspired by the poet's time living in Ireland these readings invite you into deeper ways of seeing the world. They have an incantational quality. Drawing on her commitment as a Benedictine oblate, the poems arise out of a practice of sitting in silence and lectio divina, in which life becomes the holy text.

November 16, 2019

Monk in the World: Community 5 – Suggestions for Practice ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

During this Jubilee year of sabbatical we are revisiting our Monk Manifesto by moving slowly through the Monk in the World retreat materials together every Sunday. Each week will offer new reflections on the theme and every six weeks will introduce a new principle.

Principle Three: I commit to cultivating community by finding kindred spirits along the path, soul friends with whom I can share my deepest longings, and mentors who can offer guidance and wisdom for the journey.

Consider finding one or two others in your life who might support you on your journey to be a monk in the world. This might be a spiritual director, a small faith group, or simply a friend with whom you can explore conversations of the heart, allowing each to be with your own experiences of wrestling without trying to fix it or move the other on.

Who do you want bring in to your community? What can you offer those with whom you share this journey?

With great and growing love,

Christine

Christine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

Photo © Christine Valters Paintner

November 14, 2019

Images of Mary and the Sacred Feminine from Christine's Recent Visit to Prague

Christine recently traveled to Prague for a conference on Jung, magic, alchemy, and Christian mysticism, as well as some more ancestral pilgrimage, and arrived a day early.

"I went to the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia (formerly a monastery of the Poor Clares) which now houses the medieval collection (1200-1550) of the National Gallery in Prague. I came to see the Black Madonna of Breznice, which is quite beautiful. What I found was dozens of Madonna figures, a treasure trove of sacred feminine images. Probably 80-90% of the large collection is of Mary. These are only some of them. My other favorite is the second image, Virgin Mary Expectant, I love Mary with her hand on her full belly as if she is feeling the pulse of new life and inviting us to be pregnant with God as well.  This may now be one of my favorite museums ever. Highly recommended."

This may now be one of my favorite museums ever. Highly recommended."

November 12, 2019

Monk in the World: Pat Butler

I am delighted to share another beautiful submission to the Monk in the World guest post series from the community. Read on for Pat Butler's reflection "Confession: Naked and Unashamed."

Prologue:

We use the word confession in different ways. We confess things we believe: we confess Christ. We confess ignorance: maybe about technology, when we don't understand it as well as we'd like. Jesus made the "the good confession" before Pilate. And we confess sin, admitting we got things wrong. I confess I don't always like that last one. When a Lenten devotional recommended confession as a discipline, I squirmed.

Abbess Christine advises us to lean into dissonance, however, which may hide treasures. So after squirming, I leaned in—in three movements.

Act 1: Location

Who can discern their own errors? Forgive my hidden faults.—Psalm 19:12

Confession still evokes in me images of a dimly lit church filled with dark corners, flickering candles, and a feeling: foreboding. Ahead in the gloom, at the end of a long colonnade, the shadow of the confessional loomed.

Saturday confession was a staple in my religious upbringing. As a schoolgirl, I invented sins to enter that confessional—scarcely understanding the depths or tenacity of sin. Each week I wondered: was this the day I'd be exposed as a fraud, a liar, an imposter—lying in the act of confessing?

If I went regularly to confession, no one seemed to care how much I sinned. Rather than gouging out our eyes or amputating limbs to prevent sin—Jesus' prescription—we trusted our rituals to straighten ourselves out. I was glad of it. Weekly confession was less grisly.

But eventually the ritual unraveled for me. "What's the point?" I wondered. Confession seemed like sin insurance. Through weekly confession, I could sin continually. No need to change. Accepted as a "good" Christian, I was a poor human being, living in false ways of being.

Finally, I gave up the practice, disillusioned by its uselessness in breaking destructive cycles in my life, despite my best intentions. My true motives lay naked and ashamed before God. I left the pews filled with rank and file sinners, heads bowed. The tomb-like silence of the church, punctuated by the latch of the confessional door opening and closing, seemed a place of death.

Act 2: Dislocation

Then I acknowledged my sin to you and did not cover up my iniquity. I said, "I will confess my transgressions to the Lord." And you forgave the guilt of my sin.—Psalm 32:5

Decades later, I read about confession as a place of reconciliation. Without it, the author maintained, we lose our ability to stand before God. We hide, naked and ashamed, like our first parents.

The thought arrested me. I didn't want to live like that. What would it be like to live naked and unashamed before God? I never returned to the confessional, but began the spiritual discipline of confession, with the help of Examen questions. Rather than overthinking, overanalyzing, or introspecting, I invited Abba Father to search me and try my heart. Was there any offensive way in me?

I was startled the first morning—challenged to confess fear. As I dug in, I recognized my childhood sense of foreboding. Was I still a fraud? I felt no conviction, just a need to acknowledge the fear before it overtook me. As I did so, the fear revealed its name—fear of God. Was it a sin?

The tension in my body and spirit eased and peace flooded in. I sensed God smiling, rubbing his hands together in delight, saying, "Good! Tomorrow we'll talk repentance!"

Act 3: Relocation

My dear children, I write this to you so that you will not sin. But if anybody does sin, we have an advocate with the Father—Jesus Christ, the Righteous One.—1 John 2:1

Our Advocate convicts of sin but also defends us. In my second confession, God convicted me of a sin the fear cloaked: believing the lie that if I confessed, I'd be condemned. The sin hiding in dark corners, generating fear, was exposed. Remorse swelled—with a cold-blooded decision of my will to change, to ask forgiveness.

Joy, relief, and lightness of being followed. No condemnation, only love, acceptance, and absolution.

Sometimes we need a confessional. Other times we need only our Father. Sometimes a trusted friend, prayer partner or spiritual director will do. There is strength in numbers, sharing, and community. There is humility in confessing our sins one to another.

Therefore confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you may be healed.—James 5:16

Epilogue: Assurance of Pardon

" If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and cleanse us . . ."—1 John 1:9

In two mornings, I learned two truths: confession helps us avoid sin—catching the little foxes that spoil the vineyard, that lead to sin.Staying naked and letting God cleanse. And confession is not repentance, which might come later or not at all. The word confession means simply to acknowledge. To name things.

Where we've been dislocated from the source of life, God relocates us to its full flow. His divine mercy is gracious and compassionate, slow to anger and rich in love; he forgives, absolves, and restores. Confession takes courage, trust, honesty, vulnerability—living naked and unashamed—my birthright as daughter of the Most High God.

The Seven Last Words of Jesus, Romans Cessario, OP, Magnificat, Paris/NY, 2009, 84

Psalm 139:23-24

Song of Solomon 2:15

Pat Butler is a Floridian monk, currently practicing disciplines of condo restoration and poolside meditations. Artist, poet, and writer, she has authored three chapbooks and is at work on her first book. This is Pat's third guest blog with the abbey. FB: The Mythic Monastery. IG: @monkinmotion.

Pat Butler is a Floridian monk, currently practicing disciplines of condo restoration and poolside meditations. Artist, poet, and writer, she has authored three chapbooks and is at work on her first book. This is Pat's third guest blog with the abbey. FB: The Mythic Monastery. IG: @monkinmotion.

November 9, 2019

Monk in the World: Community 4 ~ Guided Meditation by Christine + AUDIO

Dearest monks, artists and pilgrims,

https://abbeyofthearts.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/3-Community-Monk-in-the-World-Relational-Examen.mp3

This is a guided meditation experience and adaptation of the Examen prayer, developed by St. Ignatius of Loyola. He recommended it as a way to pray at the end of each day, reflecting on what has been most life-giving and life-draining. I have adapted this prayer as a reflection on your experiences each day of community and disconnection. Consider praying this several days in a row as a way of paying attention to where community happens in your life.

This is a guided meditation experience and adaptation of the Examen prayer, developed by St. Ignatius of Loyola. He recommended it as a way to pray at the end of each day, reflecting on what has been most life-giving and life-draining. I have adapted this prayer as a reflection on your experiences each day of community and disconnection. Consider praying this several days in a row as a way of paying attention to where community happens in your life.

Begin by finding a comfortable position and moving your attention inward. Draw your attention into your body with your breath. Deepen your breathing and with each inhale imagine you are welcoming in the life-breath of God who sustains you moment by moment. With each exhale imagine you are releasing whatever is keeping you from being fully present. Take a few breaths paying attention to this rhythm of breathing in the life force, breathing out what is distracting.

Become aware of the gift of this moment right now, the gift of being alive, of making space and time for prayer.

Begin to move through this past day in your imagination. As you look back over these last 24 hours, reflect on those times when you felt the most connected, whether to yourself, to another person, to God, or perhaps all three. What moments were the most life-giving experiences for you? When did you experience the joy of feeling a sense of loving another and being loved? When did you feel the goodness of being connected to another person, sharing a moment of grace, laughter, maybe sorrow? Notice if one moment in particular rises to the forefront of your awareness. Savor this experience fully. Enter into it again with your imagination, noticing how it feels in your body to be in this moment again. Take a few moments to be with this.

Is there anyone you want to thank for this memory? Spend a few moments dwelling in gratitude.

Take a deep breath and exhale.

Again, reflecting on this past day ask yourself what were the times you felt most disconnected? What moments were the most life-draining experiences for you? When did you feel a sense of loneliness? Or resentment? Or anger? Or envy? Notice if one particular moment wants some more attention and let it become your focus in prayer. Enter into this experience fully and notice how it feels in your body, notice what you are experiencing right now in response without trying to change anything. Take a few moments to be with this.

Is there anyone you want to offer forgiveness for this experience? Spend a few moments seeing if you are moved to extend forgiveness.

Take another deep breath and exhale.

Holding a heart of gratitude and forgiveness, what do you notice about these experiences? Did anything surprise you or touch you in a particular way?

How might God be inviting you deeper into an experience of community through this time of prayer?

How might you be invited to heal the places of wounding or disconnection in your life?

What is the guidance that you need to support you in any of these needs?

How might you call on God for this guidance?

Gently bring your awareness back to the room and spend some time in reflection writing about your experience and noticing the inner movements that happened.

With great and growing love,

Christine

Christine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

Photo © Christine Valters Paintner

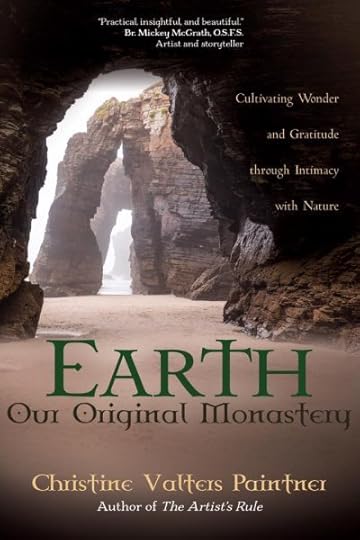

Three Upcoming Resources for 2020 – Reclaim Intimacy with Nature

I am so excited for these upcoming offerings in 2020! Three resources to help support you in reclaiming a radical intimacy with nature and sustain and galvanize you in these uncertain times.

I am so excited for these upcoming offerings in 2020! Three resources to help support you in reclaiming a radical intimacy with nature and sustain and galvanize you in these uncertain times.Coming April 2020 from Ave Maria Press:

*Earth, Our Original Monastery: Cultivating Wonder & Gratitude through Intimacy with Nature*

Isn't the cover below beautiful?

November 5, 2019

Featured Poet: Tania Runyan

Last spring we launched a series with poets whose work we love and want to feature and will continue it moving forward.

Our next poet is Tania Runyan whose work is centered on grappling with biblical themes and contradictions. Read her poetry and discover more about the connections she makes between poetry and the sacred.

Man is Without Excuse

Perhaps you could say that in Rome, Paul,

where the olive trees of the Seven Hills

strung their pearls of rain against the sky.

And yes, as I hike Glacier Park

with a well-stocked pack, I can welcome

God's ambassadors of fireweed and paintbrush,

the psalmic rhythm of lake hitting shore.

But as the refugee trudges

from Mogadishu to Dabaab, is she to catch

a glimpse of antelope bone in the thicket

and intuit the sufferings of the Son of Man?

She wears her own nails and crown.

An Eden of lizards surges at her heels,

but she wonders at nothing

but the sore-studded daughter she left to die

on the road, and now, the baby

strapped to her back: six pounds

at one year old. He no longer cries

but flutters small breaths on her neck

like the golden wings of moths

she counts with worshipful attention.

(First appeared in The Christian Century, 2012. Also appears in Second Sky.)

Themes of Her Work

Some years ago, I became obsessed with writing about scripture: women of the Bible in A Thousand Vessels, the Beatitudes in Simple Weight, Paul and his writings in Second Sky, and Revelation (I know, right?) in What Will Soon Take Place. In these books, I explore difficult themes, such as misogyny, violence, doubt, and contradictions. I've learned that facing what I would rather avoid results in my strongest writing because I have to grapple with honest feelings and doubts. Why approach God with anything less?

Poetry and the Sacred

In The Naked Now, Richard Rohr writes, "prayer is actually setting out a tuning fork. All you can really do in the spiritual life is get tuned to receive the always present message." People can access that message through traditional forms of prayer and worship or through music and art. They can find it while playing beach volleyball or filling their car up with gas. I receive it by setting out my tuning fork of poetry.

Poetry has afforded me the freedom to explore what can't be spoken with images, to reflect my feelings by tapping into sound, and to express what I "really" mean with figurative language. Playing with poetic language offers what Brad Fruhauff describes as "the freedom Christ beckons us toward, a freedom to explore and enjoy the world without shame or fear."

Without shame or fear, I can approach God boldly. With boldness comes honesty, and with honesty, intimacy. This is the presence of the sacred.

Our Sins under a Glass Sea

Jesus wanted to shout damn it to hell!

when he dropped the jar of mayonnaise,

the words not a temptation as much as succumbing

to a belief in personal justice,

cursing a world that dare exist

without intact jars and the right to fork

modified food starch through tuna on demand.

Instead, he mended the glass outside

of time and space, invited the twenty-four elders

with emerald butter knives to spread their riches

on slices of bread. He smirked at the bespattered

refrigerator door, breathed YHWH

as he hunkered over the slimy shards

with a roll of paper towels. His knuckles scraped

the floor as he scrubbed oil from the grout,

lightning flashing in the dustpan by his side.

(First appeared in Rock & Sling, 2015. Also appears in What Will Soon Take Place.)

About Tania Runyan

Tania Runyan is the author of the poetry collections What Will Soon Take Place, Second Sky, A Thousand Vessels, Simple Weight, and Delicious Air, which was awarded Book of the Year by the Conference on Christianity and Literature in 2007. Her guides How to Read a Poem, How to Write a Poem, and How to Write a College Application Essay are used in classrooms across the country. Her poems have appeared in many publications, including Poetry, Image, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, The Christian Century, Saint Katherine Review, and the Paraclete book Light upon Light: A Literary Guide to Prayer for Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany. Tania was awarded an NEA Literature Fellowship in 2011.

Dreaming of Stones

Christine Valters Paintner's new collection of poems Dreaming of Stones has just been published by Paraclete Press.

The poems in Dreaming of Stones are about what endures: hope and desire, changing seasons, wild places, love, and the wisdom of mystics. Inspired by the poet's time living in Ireland these readings invite you into deeper ways of seeing the world. They have an incantational quality. Drawing on her commitment as a Benedictine oblate, the poems arise out of a practice of sitting in silence and lectio divina, in which life becomes the holy text.

November 2, 2019

Monk in the World 3: Community ~ Reflection by Christine + AUDIO

Dear monks, artists and pilgrims

During this Jubilee year of sabbatical we are revisiting our Monk Manifesto by moving slowly through the Monk in the World retreat materials together every Sunday. Each week will offer new reflections on the theme and every six weeks will introduce a new principle.

Principle Three: I commit to cultivating community by finding kindred spirits along the path, soul friends with whom I can share my deepest longings, and mentors who can offer guidance and wisdom for the journey.

Listen to the audio version of this reflection.

https://abbeyofthearts.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/3-Monk-in-the-World-Community.mp3

Edward Sellner, in his wonderful book Finding the Monk Within, writes,

Edward Sellner, in his wonderful book Finding the Monk Within, writes,

To be a monk today or someone seeking to incorporate monastic values into his or her own life presumes being a part of a community of friends, people with whom a person can share the counsels of the heart and speak a language of the heart to one another.

Many of us have multiple communities – I consider my primary community to be my marriage. This is the place of my most intimate encounters with another person. My husband supports me wholeheartedly and we also wrestle with one another at times, as we bump up against each other's edges. I have a few very close friends with whom I can share my deepest struggles, who hold me lovingly in that space and witness my own unfolding. These are women who support me in the realization of my dreams and with whom I also sometimes wrestle when we misunderstand one another. I meet regularly with a spiritual director, a wise older man who has taught me much about being present to my dream life, my inner doubts and struggles, and the wisdom of my ancestors.

There is my Benedictine Oblate community, which is my primary spiritual community, the place where I experience the true meaning of church. For me this means having a group of fellow pilgrims who are also seeking ways to live a meaningful life in a complex world through ancient practices, who don't have easy answers, and who are willing to be alongside of me in my doubts and questions.

I also experience the great cloud of witnesses, especially my blood ancestors, as a community of support in my life. I find myself often calling upon my grandmothers – both of whom had to give up work they loved (as a dancer and a teacher) when they got married. I only knew one grandmother but I carry both of their longings in me. I live out my life in their honor and ask them to lift me up.

Beyond these core layers are people I am connected to because of something shared – like my neighbors who also love this vibrant urban place we live, and my fellow spiritual directors with whom I gather for mutual support and ongoing formation. I am connected to many other circles that gather around shared values and of course the wider communities of city, country, globe, and creation.

Then there are the communities that happen spontaneously. When we are living as monks in the world, we are paying attention to the places we see the holy shimmering. If we are cultivating our awareness and openness to these moments, we might begin to discover this kind of spontaneous community happening in more and more places.

What these experiences confirm, for me at least, is that we are all kindred spirits. The contemplative path reveals to us that we are all profoundly connected, rather than disparate people. When people ask me how they know if they are having a genuine encounter with God, I ask them if their heart is expanding with compassion, so that they see more and more people with eyes of love.

Love makes demands upon us like making our relationships a priority and being of service even when we don't feel like it. Love demands that we allow the people in our lives to be themselves without wishing they were different. In our challenges with others we are invited to welcome in the places of dissonance and notice what is being stirred in our own hearts.

In Chapter Three of Benedict's Rule he writes that when any important decision is to be made in the monastery, the whole community is gathered because "the Lord often reveals what is better to the younger." (RB 3:3) Sometimes our vision is clouded by our own expectations. Benedict invites us to welcome in the wisdom of everyone in our community. Often others can see aspects of ourselves that we cannot. You might ask someone you trust deeply to reflect back to you how they see your gifts at work in the world and the places where you seem to hold yourself back. Receive these words with reverence and humility, welcome in what they might have to teach you about your own creative journey.

Or you might pay attention to where these experiences of spontaneous community happen in your life and see if they have anything to reveal to you about your heart's deep call.

In the desert, Celtic, and Benedictine traditions, it was also considered essential to have some kind of soul-level relationship with another person who was further along the path in conscious awareness and spiritual practice. Many of you are probably familiar with the Gaelic term anam cara which means soul friend.

In the 4th-5thcenturies, St. Cassian went to the Egyptian desert to learn about the importance of an elder: "a wise, holy, and experienced person who can act as a teacher and guide for an individual or community." Of the many graces of their spiritual lives, the desert monks believed that an experienced guide was the greatest gift. Abba was the term for male wisdom bearer and amma for female wisdom bearer. Cassian firmly believed that God's guidance and wisdom comes most often through human mediation and the encounter with the desert elders. Age does not guarantee this kind of wisdom, but through a person who has been formed themselves in apprenticeship to another wise one.

An essential element of cultivating our capacity to listen is seeking out wise elders and mentors in our lives. Consider if there is someone in your life who lives with creative vitality and contemplative presence. Invite them into conversation about the ways in which they sustain themselves and nurture their way of being in the world.

With great and growing love,

Christine

Christine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

Photo © Christine Valters Paintner