Christine Valters Paintner's Blog, page 49

November 27, 2021

Advent Blessings! Please Join Us on Retreat ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

Tomorrow we begin a journey through my newest book Breath Prayer: An Ancient Practice for the Everyday Sacred. We are so excited to be diving deeply into this beautiful contemplative practice in community with our retreat starting tomorrow. I will be leading a weekly live Zoom session on Mondays (always recorded) with poetry, songs, and meditation. John will be reflecting on scripture passages which highlight breath and Amanda Dillon will be inviting us into sacred seeing with reflections on art that illuminate these passages. Wisdom Council member Jamie Marich will be inviting us into embodied practices each week. There will be reflection questions and a vibrant facilitated forum for sharing.

I offer you an excerpt from my Breath Prayer book. Because we are entering into Advent and it is a time for lighting candles I share this prayer to offer as we ignite the sacred flame and behold what it illuminates in our lives.

Lighting a Candle

I light a flameto remember

all is sacred

here and now.

The act of lighting a candle creates a shift in intention and energy of the room. Most religious traditions use candles on their altars as a symbol of divine presence or a desire for illumination. For Shabbat services every Friday evening, the candles are lit to welcome the Queen of Sabbath who bestows her gift of rest freely.

In Christian churches for Advent, each week for four weeks, a new candle is added to symbolize the light growing in the darkness. In November candles are lit in remembrance of those who have died. In churches we light candles to represent the prayers we bring. The burdens may feel heavy at time, but fire has a way of purging and purifying.

If we want to create a special atmosphere, we dim lights and set out candles. Something about the warmth of flame rather than a light bulb touches something primal in us.

How often do we light a candle in our daily lives? There are so many opportunities – at the start of the day, as we sit down to meditate or pray, when we sit down to journal or make art, for a meal, when we take a bath, when having a conversation with a beloved one.

Consider finding time each day to light a candle – to mark your prayer time, your mealtime, bathing, or some other activity you want to sanctify. Make a commitment to this act daily – both the lighting of the candle as well as the practice it accompanies.

This simple act signals to us that we are crossing a threshold, deepening our awareness of how the sacred is present here, now, always. This is true in all moments, but certain ritual acts help us to pause and remember, to pay attention. In some ways it is the physical equivalent of the breath prayer – a way to remember that the holy is here now. Lighting a candle simply magnifies what is already true and amplifies the prayer we say with our breath.

Your prayer each day might be simply to light a candle for five minutes and repeat the breath prayer gently to yourself during this time. Decide on when you will incorporate this practice into your daily rhythm. Find a candle you love, or a simple beeswax one will do. Begin with a few deep, quiet breaths as you light the lighter or strike the match. As you touch the flame to the wick offer this prayer:

Breathe in:I light a flameBreathe out:to remember

Breathe in:all is sacred

Breathe out:here and now.

Once the flame is lit, sit for several minutes just repeating this prayer while gazing on the flame. Let the flame be an anchor for your attention along with the words you are speaking. Breathing in say I light a flame, breathing out say to remember. The root of the word remember is re-member, which means to make whole again. Our loving attention and awareness reminds us of our original wholeness.

Continue the prayer breathing in, all is sacred, breathing out, here and now. The Sufi poet Hafiz writes: “Now is the time to know that all you do is sacred.”[1] And St. Benedict prompts you to remember that each moment of time is sacred, each person you encounter is sacred, and each object you interact with is sacred too.

I recommend resting into this candle-lighting breath prayer for five minutes before transitioning into whatever sacred activity you were lighting the candle to mark.

You might also call on this prayer in moments when you don’t have a candle available but are in need of reminding of the sacredness of all moments. You can light a candle in your imagination, calling forth the flame of love in your heart which St. John of the Cross describes in his poetry. This flame burns perpetually, but we can make it a practice to tend it and connect with it in quiet moments so we can remember it is always present when we need it.

To hear me speak more about the ancient practice of breath prayer, listen to the Ruah Space podcast where I was interviewed this week.

Please join us tomorrow for the Breath Prayer companion retreat for Advent. Melinda will also be leading us in a lovely slow yin yoga practice on Thursday to help us honor the slowing rhythms of winter. And next Saturday is my retreat Birthing the Holy on the wisdom of Mary and the sacred feminine for our journey.

With great and growing love,

ChristineChristine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

PS – My poem “Waxing and Waning” was published in the Bearings journal online. Click here to read the poem.

[1] “Today” by Hafiz. The Gift: Poems of Hafiz, translated by Daniel Ladinsky. Penguin, 1999.

The post Advent Blessings! Please Join Us on Retreat ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

Please send us your input for our Book Club

Greetings dear monks and mystics!

While we’re taking a short hiatus to honor Claudia’s need for time and space to grieve we thought we’d check in with all of you about how our Lift Every Voice Book Club can better suit your needs. We are very committed to continuing this work in one form or another as it is so vital to these times and we have been deeply enriched by it and are hungry for more.

WE’D LOVE YOUR INPUT ON THE FOLLOWING:

1. Do you find the *monthly video conversations* between the author, Claudia, and myself helpful? We started adding the audio files so you could listen while doing other things. What would make these more helpful? Would you prefer it to be released as a podcast format?

2. Do you find the *daily quotes and questions* posted here in this group helpful?

3. The two times we offered a *community conversation* time it was lovely but a very small group involved. Is there another way you’d feel more engaged in the conversation? Or is the video and/or daily quotes enough?

4. Would you be interested in a 3 or 4-day retreat online where we bring in our various featured authors (and perhaps some others) to lead 90-120 minute sessions which include contemplative practice? Or a series of mini-retreats throughout the year?

5. Other suggestions?

Please feel free to send us an email or leave a comment below.

With gratitude in advance for your feedback and suggestions.

The post Please send us your input for our Book Club appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 23, 2021

Monk in the World Guest Post: CJ Shelton

I am delighted to share another beautiful submission to the Monk in the World guest post series from the community. Read on for CJ Shelton’s reflection “Stitches in Time.”

As a working artist and monk-in-the-world, solitude and quiet are essential and over the past year, multiple pandemic lockdowns have provided plenty of both. Such an unexpected gift of time has allowed me to wrap myself in a self-made cocoon of reflection, to paint more and embark on art projects that might not otherwise have had room to grow.

Along with tending my creative “seeds”, another activity that has provided considerable presence during the pandemic’s downtime is the rather old-fashioned craft of counted cross-stitch. Its rhythmic process of pulling threads in and out, and over and under, is something I have found very meditative and comforting.

Like any project, cross-stitch follows a process: multiple threads need to be sorted, separated and aligned with their corresponding symbols, then correctly stitched into their proper places according to a pre-determined pattern. Each individual thread eventually weaves its part in a greater overall picture, one that is not immediately visible, but rather slowly revealed, stitch by stitch.

Along the way tangles need to be straightened out, mistakes un-picked and redone, and sometimes one simply gets disoriented by counting and recounting all those tiny little squares. Progress can seem very slow until at some point, when the fabric is spread out, you finally see just how much has been accomplished and recognize how each tangle represents a challenge worked through and each mistake something learned. The finished piece becomes all the richer for these lessons in patience and persistence.

During the pandemic I have completed numerous small cross-stitches but one large piece is still ongoing. When my mother passed away eleven years ago, among her craft things I discovered a kit she had started but never completed. The image is of a mother wolf and three pups which I suspect she chose because it reminded her of herself and her own three children.

Whether it was intuition or the gift of extended evenings, as the pandemic began, I decided it was time I finally completed it for her. To pick the project up where my mother left off felt like a sacred act, so I found myself asking for her blessing and her guidance, because oddly, there was no photo of what the finished piece should look like.

The piece is quite large and challenging so needless to say it requires patience. And I am still working on it – both the piece and the patience.

When the going gets tough, I put it aside and tackle something smaller. Or sometimes a pause is necessary to solve a problem, such as when I realized I was running out of embroidery floss. Perhaps my mother had mistakenly used three strands of thread instead of two, since along with no photo, there were no instructions either. Regardless, several trips to the craft store – lessons in patience themselves – have been required to find matching colours.

Over time I have also noticed how different my stitching is from my mother’s. On the front of the piece, this is barely noticeable; my work seamlessly merges with hers. The reverse, however, is a different story. The stitching done by my highly organized mother is distinctly unique from my own and, surprisingly, a lot “messier”. Which makes me think how much cross-stitch is like our lives.

The front represents what we show to the world, the side of us that bravely goes about our day-to-day, appearing for all intents and purposes “well put together”. The backside reflects our inner world, with all its uncertainties, its loose ends and second-guessing. It is bound to look a bit messy. Because life is messy. Our thoughts are messy. Self-doubts, anxieties, frailties, and other human foibles are always present, although sometimes not always apparent to others.

Times of challenge, especially, require that we put on a brave front. My mother survived World War II in London, England during the Blitz, so as I have stitched, I have felt her gently reminding me of what she lived through and of the resilience of the human spirit. Her experience helps put our pandemic challenges in perspective and in the wolf cross-stitch she has left a map of how to navigate such long and perilous periods in time.

We have many such maps available to us, made by both the living and those now in Spirit, but it is up to us to figure out how to complete the section of the journey assigned to us. Completions and new beginnings are rarely abrupt. Any transformative passage is usually preceded by a period of “stitching” and while the destination may be unclear at times, it is in our nature to eventually find our way.

So, I continue to patiently persevere through the wolf cross-stitch as well as other creative endeavours, because whether it is a global health threat, a seed beneath the ground, a painting or a cross-stitch, everything has its rhythm and its season.

Like those who have gone before, we too will eventually look back on the pandemic and our current challenges and see them as stitches in time, threads woven into the fabric of a much bigger picture. However big, or small, or messy, those stitches won’t be nearly as important as the maps and messages we too will leave behind, hidden within the threads of our lives, to one day be picked up and woven by others into theirs.

CJ Shelton is an Artist and Educator who inspires and guides others on their creative and spiritual journeys. Through her art, teaching and shamanic practices, CJ helps reveal the meaning, magic and mystery of the Great Wheel of Life. To learn more about CJ and view her work visit DancingMoonDesigns.ca.

The post Monk in the World Guest Post: CJ Shelton appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 20, 2021

Embrace the Sacred Feminine ~ A Love Note From Your Online Abbess

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

I am in the final editing stages of my next book Birthing the Holy: Wisdom from Mary to Nurture Creativity and Renewal which will be published in April 2022 by Ave Maria Press. I love all that this project has inspired – another compilation album of songs we are working on and the next week in our Prayer Cycle series – all coming in the spring. In the book I focus on 31 of Mary’s names or archetypes which offer windows into those qualities we can call upon in ourselves as well. The sacred feminine is not at the expense of the masculine. We need both in healthy balance to one another. The feminine values qualities of intuition, dreaming, receiving, and resting among others. We all hold the feminine and masculine within ourselves. Mary offers us many faces of this sacred feminine presence and can help us to cultivate a slower, more intentional way of being in the world.

On December 4th I will be leading a mini-retreat for the wonderful people at Spirituality and Practice where we will be exploring three of Mary’s faces – Virgin, Our Lady of the Underworld, and Mystical Rose as we go on a journey from call to incubation to holy birthing.

Here is an excerpt from my forthcoming book on Mary as Virgin:

We begin with the title of Mary as Virgin, because it is perhaps one of the most familiar and most often used names for her other than Mother. The Annunciation which appears in the Gospel of Luke is the most well-known stories of Mary and has been painted thousands of different ways. An angel appears to a young woman and issues her a life-disrupting invitation. In art, Mary is shown with varying expressions – surprise, fear, joy, peace – depending on the artist and what moment of the encounter they are choosing to illuminate.

When the angel Gabriel visits Mary, she is given a choice rather than a demand. This is perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the story, that God allows her complete agency in the decision she makes. She is being called to partner with the divine to bring a holy child into the world. Mary is active both in her openness to the choice and saying yes to the angel’s invitation, as well as surrendering to the divine desire: “Let it be done to me.” This is an aspect of the sacred feminine at work – this holy yielding to what is being offered. The divine unfolding is dependent upon Mary’s full “yes.” Contemplative teacher Cynthia Bourgeault highlights that in this moment, it is God who waits upon Mary.

Jungian analyst Marion Woodman described the virgin archetype as having less to do with physical intactness and purity, as it does with emotional wholeness and sovereign power. The Virgin archetype is whole, belonging to herself, and impregnated with divine love. “She is who she is because that is who she is.” She is free of the dictates of family and culture. The Virgin reconciles all opposites within herself and has everything she needs within to bring new things to life.

Theologian Elizabeth Johnson describes the archetype of virgin this way: “More than a biological reality, being a virgin indicates a state of mind characterized by fearlessness and independence of purpose. Whether wife or mother, the virgin retains an inner autonomy. . . When this becomes the lens for interpreting Mary’s virginity, the resulting image can function spiritually and politically to encourage women’s integrity and self-direction.” This can be a much more empowering image of Virgin than we have traditionally received where Mary is often upheld as an impossible model of femininity.

Devotion to Mary as Virgin means being drawn to the power she contains within herself and radiates out generously to the world. We are drawn to her because she is a mindful and loving presence who reflects this gift back to us. She empowers us to find this independence of purpose and autonomy within ourselves.

The Virgin archetype invites us to integrate both the feminine and masculine energies within us, cultivating a deep connection to the divine within, and open ourselves fully to our own inner resources. She reminds us that ultimately we do not rely on anyone else for our sense of power and presence in the world other than the divine spark within. She insists that we have full consent over the direction our choices take us.

Sadly, the church tradition around virginity has held quite strongly to Mary’s perpetual physical virginity as the dominant aspect of her being. The early church’s upholding of the status of virginity as a holier kind of human state has often led to scorn for the physical, material, and sensual world. Mary has been used to uphold a model of femininity that is very restrictive and rejecting of the beauty and sacredness that sensuality and sexuality can offer to our lives. The shadow is what remains unconscious. All archetypes have a dark or shadow side which can be harmful when acted from without seeing clearly. For example, in the monastic tradition there has been an elevation of the path of virginity to a point that the body was often denigrated. It can encourage a dualistic approach to the world where body and soul become divided from one another.

Rather, the Virgin Mary calls each of us to consider our own innate wholeness. What are the messages we receive from family and culture that tell us we are somehow incomplete unless we lose weight, become more productive, earn more money, gain more success? Claiming the Virgin archetype means not questioning our worthiness and knowing that with every invitation, we hold the power to say yes or no. So many of us feel stretched thin by too many commitments and we forget that with every yes we respond with means we are also saying no to having enough energy for something else that might be important to us. Often this means self-care is necessary without apology and the nourishment needed to deeply replenish ourselves, avoiding burnout, and being of service in the world.

If you’d like to make some time during Advent to invite Mary to guide you more deeply into your own journey of holy birthing please join me on December 4th.

(And if you’d like to go more deeply into Breath Prayer as a companion retreat experience to my book, we are starting a 4-week series on November 29th.)

More ways to celebrate Advent with us below including a lovely yoga class with Melinda, a contemplative prayer service with Simon and me, and a retreat I am leading for Spirit of Sophia Center on The Spiral Way and Celtic Spirituality. See details below.

With great and growing love,

ChristineChristine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

Image credit: © Kreg Yingst (you can )

The post Embrace the Sacred Feminine ~ A Love Note From Your Online Abbess appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 16, 2021

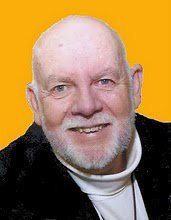

Monk in the World Guest Post: John Spiesman

I am delighted to share another beautiful submission to the Monk in the World guest post series from the community. Read on for John Spiesman’s reflection “A Threshold Journey.”

I have been thinking a lot about thresholds in this challenging and uncertain time of global pandemic. A threshold is the space between — something old and new, between an end and a beginning, between something known and unknown. This time for me has been a time between old and new, between an end and a beginning, and between something known and unknown. This time has encouraged me to wonder what happens when I approach a threshold, what and who will I be as I approach the threshold, as I walk through the threshold, and on the other side of the threshold. I know I have generally resisted not only these thoughts but accepting this as a threshold time for me because of the unknown. In my humanness I definitely (many times) approach the unknown with reluctance, even though I well know that one of the constants of my humanity is CHANGE. I have come to believe that this time I am experiencing is truly a thin time and am reminded that something new and beautiful is unfolding in me and throughout the Earth. I am filled with awe, wonder, and gratitude. This is truly a time of death and resurrection –AND all its opportunities for soul work.

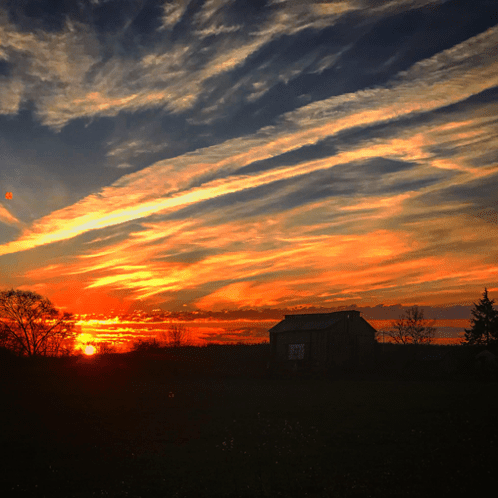

Picture: Dream a New Day. November 20, 2020 ©John Spiesman

Picture: Dream a New Day. November 20, 2020 ©John SpiesmanDuring this time of global pandemic, I have been drawn to Christine’s book, The Soul’s Slow Ripening, in which she states that thresholds demand that we step into the in-between place of letting go of what has been while awaiting what it still to come (p. 3). What a unique call this is for a man entering life’s fourth quarter, pondering and reflecting on all that has come before. What could possibly be left to ripen in a fourth quarter soul, I’ve wondered. Then I remind myself that eternal time of the soul is not linear, and the pandemic the Earth has experienced is a mere blink of the eye in the non-linear time of the Universe. I have worked extremely hard to do as Christine suggests – to release my need to control the outcome of this time, and to allow this time to be a threshold time for me just as it is for our beloved Earth.

This threshold time has become a time of discernment for me. I ponder who I was before March of 2020, and anticipate who I can be in the last months of 2021, or in 2022. I have learned to savor this time between to think about possible next steps in my earthly journey – a season has perhaps come to an end – and just what might that mean – Just what is a liminal time, and how has this past 19 months been liminal? I think the most difficult part is being in a time between and knowing that there are things that must be let go so that I can continue to grow and evolve in my own consciousness, depth, and life journey. This letting go, I know, leads to rebirth.

I wonder what could happen if, during this time of uncertainty, confusion, and fear, I (and we collectively) could allow a time of rich and graced transformation to enter the picture? Would some of our anxiety and fear disappear if we were able to look at this time as an in-between time, and let go? What might happen if we stayed grounded, centered, connected to the Earth and Universe while searching for a sign of something new to begin to come forth?

Jungian Analyst Angeles Arrien reminds us that throughout time, thresholds and gates have been symbolic of passageways into new worlds. She notes that these symbols are imprinted in our psyches and announce the possibility of new life or even a new identity. Arrien says that gates and thresholds offer “an opportunity for communion between different worlds: the sacred and profane, the internal and external, the subjective and objective, the visible and invisible, and the waking and dreaming.” (p. 9*) This has certainly caught my curiosity as these months have continued to linger on – and just about each of Arrien’s examples hold true for me – I am clearly passing from a pre-pandemic to post-post pandemic world whether I like it or not, and there is definitely a new identity on the horizon as I begin to emerge – one in which I am so much more aware of the sacred, the internal, the invisible and the dreaming – filled with gratitude for having that opportunity for communion between these two worlds in which we find ourselves. I have been able to discern perhaps for the very first time just what communion is – with the universe and with all creation – and find myself holding space for myself, for others, and for the Earth as something new is being birthed. Arrien suggests that a threshold is the place or moment where transformation, learning, and integration occurs, while a gate is the place of protection and testing, essential before the entry to the threshold – so perhaps part of this Covid-19 experience has been the gate, and part the threshold – definitely something to continue to ponder as I process the test and protection, the learning and the transformation with gratitude and hope.

Christine’s discussion of Seasons of a Lifetime (Sacred Time: Embracing an Intentional Way of Life) makes me yearn for that rhythm of life that has been true. I am reminded that For Everything there is a Season (Ecclesiastes 3:1), and have learned that within and between seasons there can be tension – perhaps the tension of being at a gate….. or perhaps the tension of approaching a threshold…. Or even a tension of living between. I feel strongly that collectively these past months have brought us all into this tension – definitely grief and joy together, and for me, the tension of old and new – of cleaning my personal house and discerning what my interior self might look like when the Earth is borne anew in its post-pandemic form, and most essentially, ponder as Christine suggests, “What is it the season for?” (p.87). What a gift this has been, an opportunity of and for slow discernment. My prayer is (for myself and all the Earth) that this practice will be ours together.

I spent many, many days dreaming a new day, and in closing, offer this poem.

Dream a New DayDream a New Day

Joy, Sorrow, Hope?

Dancing together at sunrise

The Universe awakens

Joy, Sorrow, Hope?

The Dream Maker knows

The Universe awakens

A gift revealed

The Dream Maker knows

Connection with Divine

A gift revealed

Isolation, Despair or Hope?

Connection with Divine

Dancing together at sunrise

Isolation, Despair or Hope?

Dream a New Day

Some of my favorite books:

Arrien, A. (2007). The Second Half of Life: Opening the Eight Gates of Wisdom. Sounds True. Louisville, CO.

Valters Paintner, C. (2021). Sacred time: Embracing an Intentional Way of Life. Sorin Books. Notre Dame, IN.

Valters Paintner, C. (2018). The Soul’s Slow Ripening: 12 Celtic Practices for Seeking the Sacred. Sorin Books. Notre Dame, IN.

John Spiesman has journeyed in formation as a spiritual director, and in dream work through The Haden Institute. Formed in the Jungian Mystical Christian tradition, he welcomes and accompanies journeyers who long for a deeper relationship with the Divine. John’s interests include spiritual symbols and ritual, church wounds, vocational calls, the Celtic Anam Cara and Celtic Spirituality, the sacred masculine journey, the empath’s journey, as well as intuitive dream work, and dream work in psychotherapy. John has been a career educator, and currently serves as a Licensed Independent Social Worker, pastoral counselor, spiritual companion and dream worker in Ohio, USA. He can be reached through his website: www.spsj.care.

The post Monk in the World Guest Post: John Spiesman appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 13, 2021

Monk in the World Video Podcasts (Creative Joy) ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

It is with great joy that we share our final video podcasts for morning and evening prayer in the Monk in the World prayer cycle. Our last principle of the Monk Manifesto is Creative Joy! This principle is about cultivating our practice of being a dancing monk in the world and allowing wonder and delight to guide our days. If you’ve been enriched by these free resources for prayer, please consider offering a donation to help support our continued development of the prayer cycle. We are grateful for the generosity of this community.

As the season of Advent approaches, we invite you to join Betsey Beckman and Kathleen Kichline next Friday – Saturday, November 19-20th for a mini-retreat Once Upon a Time in a Town Called Nazareth. This will be a time of Sabbath to journey with the young Jewish girl, Mary as she encounters the Angel Gabriel and says “yes!” to God’s call. Through creative practices, ritual, and imagination, we will explore how God calls each of us to the gift of incarnation and invites us to the birthing of new life. It’s a wonderful way to enter Advent and practice the principle of Creative Joy! Below is a reflection by Betsey and Kathleen.

Advent comes around each year and offers such a lovely chance to contemplate Mary as a vessel of incarnation and invitation to us all. Luckily, we (Kathleen Kichline and Betsey Beckman) have discovered that this is a subject the two of us are equally passionate about! Hosting Once Upon a Time in a Town Called Nazareth. has become an annual live event, and this past year we discovered our retreat adapts to life online beautifully, surprising even us with how meaningful, intimate, and beautiful it can be.

Sabbath is a subject near and dear to Abbey aficionados and has recently been explored by Rabbi Zari Weiss in her retreat at the Abbey. For our retreat, framed by the beautiful rhythms of Shabbat, we enter the “once upon a time” story, and go back to a time before the world knew of how God’s unique incarnation on Earth would take place, before the Christ’s inbreaking changed history forever. Friday evening sets the stage, as we join in welcoming Sabbath just as a young Jewish girl would have done in her small first-century town in Palestine. With Mary, we enter a time of not-knowing, and expectant waiting within our own lives. On Saturday morning, all heaven breaks loose! We witness how God’s messenger in angelic form visits this young girl asking her to be a part of the Divine plan. Her remarkable response and our invitation to do the same, is explored through story-dance, art, poetry, and prayerful reflection. This timeless moment becomes incarnate again, here, and now in our lives and world.

Both Kathleen and I (Betsey) know the terrifying and awe-inspiring moments of experiencing Spirit in our lives, and we share a common passion for responding with courage and humility. If you’ve attended many events at Abbey of the Arts, you will know that my response includes carefully cavorting across mountaintops and through monasteries, playfully dancing with life and inviting you to join in! I am delighted to introduce you to my friend and colleague, Kathleen Kichline, who has journeyed deeply into the scriptural stories of women and finds inspiration there to live her own life’s “Amen.” She has a gentle, thought-provoking approach to the stories in Scripture that teases meaning out and invites the listener in. I am excited about her forthcoming book: WHY THESE WOMEN? Four Stories You Need to Read Before You Read the Story of Jesus.

It is a joy for Kathleen and me to work together and inspire one another. The bond between us and the immediacy of our interaction has become a tangible part of the retreat itself. This year, our retreat will take place before Advent begins and will hopefully set the stage for a rich season of joy and reflection. We are so pleased this year to invite the community of Abbey of the Arts on this journey to Nazareth and back again through the gift of Sabbath.

With great and growing love,

ChristineChristine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

The post Monk in the World Video Podcasts (Creative Joy) ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 9, 2021

Monk in the World Guest Post: Kathleen Deyer Buldoc

I am delighted to share another beautiful submission to the Monk in the World guest post series from the community. Read on for Kathleen Deyer Buldoc’s reflection “Window of Hope.”

I soften my gaze as I stare out my study window, looking beyond what is to what was and what is yet to come.

My mother is dead, lost with hundreds of thousands of others to Covid19. She fought her way to the end, as stubborn in dying as she was in living. Dementia stole most of her memory, but it didn’t steal her will to live.

This window frames a garden. Beyond the garden is a gated fence, and beyond the gate, a meadow. Spring is working its magic today, the earth bursting with new life. Such a metaphor for the old aphorism, life goes on. It’s nearly five months now since Mom died. Thank God for hospice, who made sure we could sit vigil with her at the end.

I never dreamed that holding a hand could act as an intersection between heaven and earth; an attachment between two people standing at the portal, one hovering, not-quite-ready to cross over the threshold; the other firmly grounded on this side of the opening. Like the ghost pains from an amputated limb, I still see and feel Mom’s hand in mine; can still smell the Jergen’s Lotion I used to massage that hand during her last days.

My mother loved this window where I sit today. When I walked her through our new home ten years ago she looked out at the spring garden, lushly blooming with daffodils, lilacs, and a profusion of dame’s rocket. She turned to me, her face aglow, bouncing on the balls of her feet. This is it! This is yours! Yours, Kathy! All yours!

I thought she meant the house and garden, but I’ve come to believe she meant this room, this window, this view.

It’s taken me ten years to claim this room as my own. A room for writing and dreaming and praying. A room where I do the work of reflecting on who I am, on whose I am, on what the events of life might mean. For ten years we used it as a guest suite, part of our retreat center, Cloudland, where we welcome friends and strangers alike to spend time alone with God. This room seemed perfect, with its window view of the garden, its second window looking out over the fields. My room could wait, I thought. My room could wait.

Dementia was just beginning to work its insidious way through Mom’s brain as she stood at this window ten years ago. Today, looking back, I remember how I thought her words a little strange as she bounced up and down, clapping her hands. What does she mean, I wondered, it’s yours, Kathy, all yours?

Mom enjoyed working when she married my father in 1951. Her salary helped put him through college. But once I was born she did what the majority of women did in the 50’s. She became a full-time homemaker. I chose the same path when my first-born came along. My vocation as a writer came a few years later, and as a spiritual director, several years after that.

Sitting here today, looking out my study window, my attention is attracted to movement in a tree far off in the meadow. It’s a large woodpecker, pounding rhythmically at the walnut tree. What perseverance it needs to gather its food from such hard wood. The same perseverance we need as moms to find a place of our own when raising a family, especially those of us with children with disabilities or mental illness. Even later in life, when our children are gone, we can still find ourselves putting everyone else—even strangers—first, because that’s what we’ve been taught to do.

[image error]My mother never found that room of her own in her home, but she did find it in her garden, where she puttered endlessly after my father died at the tender age of 49. Mom was just 48. She often told me that planting seeds—cosmos, marigold, zinnia—gave her hope. I believe that’s what she saw for me as she danced in front of this window all those years ago. Hope. She caught a glimpse of the future me sitting here, watching the seasons come and go—spring, summer, autumn, winter—one following the other without fail. She glimpsed the hope of dancing daffodils in the spring, wildflowers setting the meadow aglow in the summer, brilliant leaves in autumn, and snow blanketing the fields in winter.

My mother knew I needed a place of my own, after 25 years of raising a son with autism. She knew I needed a window like this to act as a portal into the future as I stepped into the danger and mystery of who I might yet become.

I soften my gaze as I stare out my study window, looking beyond what is to what was and what is yet to come. I hear my mother’s voice clearly. This is it! This is yours, Kathy! All yours!

I never dreamed that the memory of holding my mother’s hand could act as an intersection between heaven and earth. All that exists between heaven and earth is here, in this room, in this present moment, framed by a window of hope.

Kathleen Deyer Bolduc is a spiritual director, author, and founder of Cloudland, a contemplative retreat center. Her books, including The Spiritual Art of Raising Children with Disabilities, contain faith lessons learned parenting a son with autism, and finding healing and restoration through the spiritual disciplines. KathleenBolduc.com

The post Monk in the World Guest Post: Kathleen Deyer Buldoc appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 6, 2021

Monk in the World Video Podcasts (Conversion) ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

Today we offer you the gift of morning and evening prayer from our Monk in the World Video Podcasts on the theme of Conversion. Conversion may sound harsh to some ears, especially when it comes from a place of wanting others to be different, to be changed.

In the Benedictine tradition, however, conversion is about a lifelong commitment to our own transformation. It is acknowledging that we are always growing and learning, we have never fully “arrived.” Conversion is a commitment to always beginning again, to know that we will falter in our passion and desire. I like to think of it as being open to holy surprise.

Conversion has been at the heart of our Lift Every Voice book club as well. I started 2021 with a desire to root myself more deeply in the monastic principle of humility. I knew reading voices from more diverse perspectives would be deeply enriching and would be one way to commit to my own ongoing transformation. I have been so enriched and am hungry for more.

Our book for November is Soul Care in African American Practice by Dr. Barbara Peacock. This is a beautiful book about contemplative practice rooted in the Black church tradition. Dr. Peacock uplifts practices like lectio divina and spiritual direction and situates them firmly at the heart of African American practice. She also uplifts Christian mystics like early church fathers Tertullian and Augustine who are known for their contemplative contributions, but mainstream religious history has not emphasized their African heritage.

She writes: “If a greater percentage of African Americans were aware of the rich contributions of our ancestors – it would change our thinking, our views of the Christian faith, and consequently change the face of Christianity.” This is part of the conversation I am so excited to be a part of. To broaden our understanding of mysticism by uplifting more voices.

Dr. Peacock writes movingly from her own experience of burnout as a pastor and how she sees God’s lavish desires for us to simply rest in the divine presence:

“It is a beautiful experience to carve out extensive time with (God), and it is also a glorious event to be in the moment with him, just appreciating a conscious, fresh breath of his presence. A selah moment. A pause. A time to stop and be with your Creator, your Savior, your God, your friend, your companion. How precious it is to rest in his presence, rest in his arms, rest in him. Just being. No doing. Selah.”

I know part of my own ongoing conversion is to commit again and again to those true pauses or selah moments.

She also writes beautifully about how the “legacy of African Americans extends beyond what is physically visible and mentally comprehensible. Our trials and tribulations have birthed an eschatological hope that is perpetually undergirded by prayer and by directives from Yahweh.” Through my reading this year as part of this book club and beyond, I have been so moved to understand this profound hope born from a legacy of oppression and the vision it offers for us collectively. It feels essential to the times we are living in.

You can listen to the video conversation Claudia and I had with Dr. Peacock. Toward the end Claudia asks her to lead us in a meditation which was a really beautiful experience.

Please note that my wonderful book club conversation partner, Claudia Love Mair, recently lost her oldest son to a drug overdose. To allow her some time for her bereavement we are cancelling our community conversation for November and December and our featured book for December – Womanist Midrash – will be postponed until February 2022 when we will launch a new year and a new series of books to explore. The November video conversation was recorded prior to this and the daily quotes and questions for the book will still be posted in our Facebook group during November to help you deepen into your own conversation with the text.

Please pray for Claudia, her son, and her family as they travel this painful path. She has been writing some beautiful reflections on her grief and will be sharing some of that with us here in the weeks to come.

With great and growing love,

ChristineChristine Valters Paintner, PhD, ReaCE

The post Monk in the World Video Podcasts (Conversion) ~ A Love Note from Your Online Abbess appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 3, 2021

Monk in the World Guest Post: Bart Brenner

I am delighted to share another beautiful submission to the Monk in the World guest post series from the community. Read on for Bart Brenner’s reflection on filling the cup

You are the wine, / I am the cup.

I can yield nothing till I am filled up.

(O Sun, Earth Our Original Monastery Prayer Cycle: Morning Prayer, Day Six)

The pandemic brought illness and death, and a strange way of living—lock down, masking, and social distancing. Living in a cloistered community was was not welcomed by many. As an octogenarian, living alone since the death of my wife six years ago, the pandemic gave a new meaning to hermitage. How would my cup, as an introverted monk, be filled up during this time of external restrictions?

Even with restrictions, it became necessary for me to travel. My 105 year old mother had entered in-home Hospice care. I was part of the care team for the last three weeks of her life. Lovingly tending to life at its end helped fill my cup.

Upon returning home, I began to fill some of the extra alone time caused by the pandemic with riding my newly purchased ebike. I named my bike The Quest because it takes me into nature’s amphitheater and gives me time to reflect on matters both substantive and mundane. These reflections have helped fill my cup with deeper appreciation for the blessing of a weak faith.

A wise teacher once told me that it doesn’t matter what size cup you hold—demitasse or beer stein. In the kingdom, it will be filled to overflowing. Perhaps a weak faith is enough. After all, faith is not a possession.

John Caputo teaches that “God does not exist, God insists.” It is not so much that I have faith but, rather, that faith has me. Faith insists—disturbing me, stirring me up, inflaming me. Faith resides in my heart (or my guts), not my understanding. The understandings come later. Faith is simply the pre-disposition to pay attention to the insistence that comes in the name of God. Faith itself is weak because it come without a plan of action.

When The Quest and I go out on an overcast day, I am reminded of the Cloud of Unknowing—the cloud that comes in the name of God, insisting, luring me from the heights and the depths. In the midst of that unknowing there is that trace I call faith. It fills my unknowing, not with knowing but with curiosity and seeking.

Faith opens my emptiness. My studies (especially seminary) taught me to fill that emptiness with theological understandings and a solid belief system. I have slowly learned to look beneath those beliefs, for they are simply opinions—hopefully informed opinions, but opinions nevertheless. Underneath is the trust that hides itself in faith—trust in myself, trust in others, trust in the creation. Radical trusting opens me to the insistence, the trace, lure, or nudge. These can become the call to action that comes in the name of God.

Two months of attending to the daily prayer services of the Abbey of the Arts has reminded me of something I knew so well as a child. The creation is our original cathedral, our current spiritual directors, and the fount of sacramental liturgy. Churches, Sunday schools and seminaries are secondary resources.

For me, this was summed up in the reading from Teilhard de Chardin (Earth Our Original Monastery Prayer Cycle: Morning prayer, Day One): “By means of all created things, without exception, the divine assails us, penetrates us, and moulds us. We imagined it as distant and inaccessible, whereas in fact we live steeped in its burning layers. . . The world, this palpable world, which we were wont to treat with the boredom and disrespect with which we habitually regard places with no sacred association for us, is in truth a holy place, and we did not know it.”

The event of faith is an unspoken lure (an insistence, a nudge, a call) that, when heard and recognized, disturbs my status quo, upsetting plans and hopes. Understandings come later, along with the riskiness of deciding whether to follow where the lure leads, often without full knowledge. This riskiness of faith touches my passion, fuels my energy, and offers me integrity. What I have been describing is “the weakness of faith.” For the trace, the lure, the call comes gently (even weakly) as an invitation—disturbing me in the night, disrupting my mid-day. Even though it comes in the name of God, it has no power except for my response. When I listen and respond, my cup is filled to overflowing. If I ignore the invitation, if I refuse to answer faith’s call, faith retreats.

Thankfully, the creation does not retreat. The birds continue to sing, the seasons change, the brook babbles, the silent stone remains implacable in the face of my hesitations. As The Quest and I wander out into nature’s amphitheater, as I watch the redbud trees burst into their springtime glory, as I gaze into the vastness of the sky, I am reminded that I am but a small (sometimes even marginally important) part of this vast and wondrous creation, a cup waiting to be filled up. The shimmering of faith that dawns within me and the glimmering of hope that accompanies it both call me to dance with Amma Syncletica and kindle the divine fire within. As we dance, we also sing, “Breathe into the Earth, Holy One and renew us; it’s a new day.” (Earth Our Original Monastery Prayer Cycle: Closing Song, Morning Prayer, Day Six)

Bart Brenner is a retired Presbyterian minister. He is an avid genealogist, fly fisher, and ebiker. He enjoys watching his grandchildren grow into a young woman and a young man. He is co-author of Stirring Waters: Wrestling with Faith in a Restless Age.

The post Monk in the World Guest Post: Bart Brenner appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.

November 2, 2021

Lift Every Voice: Contemplative Writers of Color – November Video Discussion and Book Group Materials Now Available

Join Abbey of the Arts for a monthly conversation on how increasing our diversity of perspectives on contemplative practice can enrich our understanding and experience of the Christian mystical tradition.

Christine Valters Paintner is joined by author Claudia Love Mair for a series of video conversations. Each month they take up a new book by or about a voice of color. The community is invited to purchase and read the books in advance and participate actively in this journey of deepening, discovery, and transformation.

Click here to view this m onth’s video discussion along with questions for reflection.

Soul Care in African American Practice by Barbara Peacock illustrates a journey of prayer, spiritual direction, and soul care from an African American perspective. She reflects on how these disciplines are woven into the African American culture and lived out in the rich heritage of its faith community.

Join our Lift Every Voice Facebook Group for more engagement and discussion.

The post Lift Every Voice: Contemplative Writers of Color – November Video Discussion and Book Group Materials Now Available appeared first on Abbey of the Arts.