Ian Reid's Blog, page 9

June 17, 2015

Beyond Narcissism – a better class of blogger?

Source: Creative Commons

There’s no denying it: we bloggers generally tend to be self-absorbed and self-promoting. I can hardly claim that the thought-bubbles I blow on this website are much of an exception. Although what I post here isn’t always about me and my writings, the topics and opinions reflect shamelessly (or should that be shamefully?) who I am. And there’s something brazen about the notion that anyone out there might have the slightest interest in what another person thinks on the subject of writing or anything else.

Source: Creative Commons

Yet despite the presumptuous and tendentious nature of all such on-line activity, some of its exponents – a better class of blogger? – manage to be less narrowly narcissistic than others. One literary blog that I admire for its generous hospitality to other writers is Amanda Curtin’s Looking Up, Looking Down. Of course her site is informative about her own work and interests, among other things, but she also makes a point of regularly inviting guests aboard – providing an introductory comment on some author she knows and a simple structure of questions (“2, 2 and 2″) to which the guest responds. So it functions like a set of prompts for a mini-interview, usually focusing on a newly published book.

I’m delighted that her latest post gives me a publicity platform for a few remarks about my novel The Mind’s Own Place. Thank you, Amanda!

The post Beyond Narcissism – a better class of blogger? appeared first on Reid on Writing.

June 3, 2015

Can you judge a book by its cover?

When moralists tell us “Don’t judge a book by its cover”, we know it’s a proverbial injunction to look beneath superficial appearances, particularly in our dealings with people. A suave demeanour may belie inner unworthiness, while an exterior that’s not prepossessing may mask valuable qualities. Yes grandma.

However, the publishing industry takes a more literal view. It usually invests great care in cover designs on the assumption that prospective customers can be decisively influenced by what they see on the outside of a book. Consciously or not, one’s choice to buy this book rather than that may often turn on the visual and textual information displayed on front and back. We tend to draw inferences about genre, subject matter and style not only from the descriptive blurb but also from the designer’s selection of images, colours, even the typeface used for the title or author’s name.

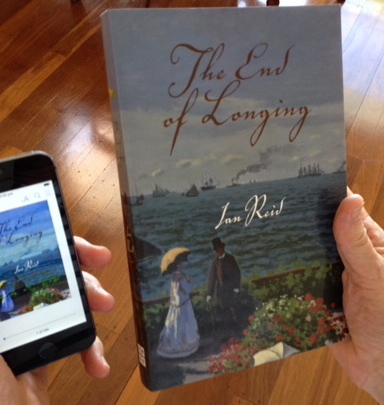

In choosing what to read, don’t you tend to judge a book by its cover? Take the following example, from a forthcoming book (release date: July 1st) in which I have a keen interest.

This front cover gives you (doesn’t it?) an immediate impression of the kind of book this is. Leaving aside for a moment the title, and the possibility that the author’s name will be associated with things previously read or heard, the scene depicted here suggests a story that’s set in the past, apparently in a frontier society and a colonial period. Though fictional (the subtitle says “a novel”), it seems likely to be grounded realistically in a specific time and place.

Having seen an advance copy of this book, a friend comments in an email message to me: “I very much like the choice of cover image – figures occupying distinct frames but situated within the same space – such lovely resonance with your novel’s themes.”

Prospective readers who happen to know something about 19th-century artists in Western Australia may recognise the image of Bunbury’s Rose Hotel. It reproduces part of a picture painted in 1863 by a white-collar convict called Thomas Browne, not long after his transportation. The original, in watercolour and pencil, is in the National Gallery of Australia. A trained draughtsman, architect and engineer, Browne produced other artworks that are held in various public collections. And a fictional version of him is one of the main characters in this novel.

If what’s on the front of a book arouses interest, a potential buyer will then usually glance at the back cover for more information. A particular publisher’s logo can serve as a token of quality. There may be an endorsement in the form of a brief quote from a reviewer. The blurb should indicate whether this is the kind of book that the person now holding it would probably enjoy reading. And the visual appeal of the back cover can be influential, too: often it extends the image on the front cover, as in this case.

I’m fortunate that my publisher UWAP has a well-deserved reputation for excellence in book design, and pleased that my idea of reproducing Browne’s painting on the cover (with permission from the National Gallery) was readily accepted.

We did discuss the possibility of using another image, also connected historically to Thomas Browne; here it is.

The eventual decision to put this strange and sombre image inside the book, facing the first page of text, was a clever solution. It’s a photograph from about 1890, showing the Old Mill in South Perth after Browne modified it. The source of the image is the Battye Library.

Being much bleaker than the sunlit 1863 watercolour picture used for the cover, it foreshadows one of the narrative trajectories in this novel.

Oh yes – the novel’s title: The Mind’s Own Place is an odd phrase, and someone looking at the cover may be a bit puzzled by it. I hope it stimulates curiosity. Perhaps it may ring a bell for a person who is well versed in one of the great classics of English poetry. Here’s a clue: the real-lifeThomas Browne was known by the nickname of Satan.

The post Can you judge a book by its cover? appeared first on Reid on Writing.

May 27, 2015

The War’s Not Over Yet: instalment 2

The novelist Anthony Doerr has remarked that there will soon be nobody left on earth who can personally remember World War 2.

In a previous post I discussed a few recent examples of “postmemory” writing (to borrow Marianne Hirsch’s term), where authors are retrieving and pondering the traumatic wartime experiences of an earlier generation – often parents, grandparents or other older relatives – even when the genre is notionally fictional. Their stories, I suggested, seem driven by a desire to expiate or exorcise – or simply to ensure that some memories of World War 2 are not forgotten.

Here I’ll pursue this theme in relation to three more novels. The first is by Anthony Doerr himself, and it’s one of the most impressive works of historical fiction I’ve read for a long time.

All the Light We Cannot See creates a powerfully sustained tension by using the perspective of children (one French, one German) to dramatise the build-up to World War 2 and the subsequent devastation. Its early chapters quickly drew me in and the device of frequent alternation between the stories of the two main characters, mini-chapter after mini-chapter, held my interest throughout.

Already on the first page there’s a tensile quality in the writing:

LEAFLETS

At dusk they pour from the sky. They blow across the ramparts, turn cartwheels over rooftops, flutter into the ravines between houses. Entire streets swirl with them, flashing white against the cobbles. Urgent message to the inhabitants of this town, they say. Depart immediately to open country.

The tide climbs. The moon hangs small and yellow and gibbous. On the rooftops of beachfront hotels to the east, and in the gardens behind them, a half-dozen American artillery units drop incendiary rounds into the mouths of mortars.

That quality, blending the stark with the lyrical, never slackens. It’s August 1944 when the book opens, and fierce bombardment of the historic French town of Saint-Malo is imminent. Two months after D-Day, with half of western France now liberated, this last German stronghold on the Breton coast faces destruction. As the waves of bombers approach it, two teenagers who are unknown to one another become the dual nodes of the narrative: a blind and seemingly helpless French girl is hiding in an attic, separated from her family, while a young German soldier with a flair for radio technology is sheltering nearby in a hotel cellar.

The gradual unfolding and suspenseful convergence of their stories is handled with great skill. More than anything else, what holds it all together tautly is the consistent stylistic control. Poised, precise, the language rings true. Rhythm and tone never seem forced.

The title image works on several levels. Light suffuses the action, yet one of the main characters cannot perceive any of it. Besides, another kind of electromagnetic radiation is pervasive in this novel – the wireless transmission of sound. Much of what happens is dependent on radio waves, which are of course invisible, a form of “light we cannot see.” The author says in an interview:

I wanted to tell a story [about] a time in history when radio had a lot of power. When hearing the voice of a stranger in your home was a magical thing. So I knew I’d have to go back to World War 1 or World War 2.

He chose the latter period because the rise of Nazism and the devastating impact of German propaganda were made possible by radio. That technology was a key to the terrible events of the 1930s and 40s.

One slight reservation about Doerr’s fine novel: by prolonging the story far beyond the war years he risks weakening its impact. I can well understand, and forgive, his reluctance to take leave of such memorable characters; but the novel’s centre of historical gravity is 1944, and when the final chapters stretch forward to 1974 and then 2014 it’s as if the author feels compelled to affirm (needlessly?) the lingering power of “postmemory” through a narrative relationship between his own generation and those wartime predecessors.

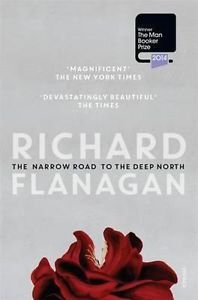

The other two recent war stories I’ve been reading are prize-winners by notable Australian authors: Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North, a story of Australian POWs, and Steven Carroll’s A World of Other People, which mostly takes place in London during the Blitz but also dramatises its aftermath by focusing on a traumatised Australian pilot. This pair of works controversially shared the 2014 Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction after the PM himself insisted that Flanagan’s should be placed alongside the judging panel’s strong preference for Carroll’s. Flanagan also won the Booker Prize for his novel.

Both have arresting qualities, but neither of them, I’m sorry to say, has aroused in me the passionate admiration evidently felt by many readers, though I don’t intend to provide here a full-on critique. As a general rule I think Australian novelists should hesitate to review in negative terms the work of other Australian novelists – not so much to avoid the risk of reprisals as just to acknowledge that our national literary scene, being small and commercially frail, is not well served by internecine strife. Yet in this case, having committed myself to a couple of blog posts about recent WW2 stories, I can hardly avoid mentioning these two acclaimed novels – and it would be lily-livered to disguise the fact that they underwhelmed me. (Both Flanagan and Carroll are well-established and highly successful writers, so my murmurings won’t inflict any harm on their secure reputations.) Perhaps it may be worthwhile to ponder why, despite the plaudits The Narrow Road to the Deep North and A World of Other People have attracted, I’m by no means alone in my inability to be totally enthusiastic about them.

The main problem, perhaps, is that they tend to become over-insistent on their messages. In The Narrow Road, for example, despite powerful scenes and images that linger in the mind, too much of the prose can seem overwrought and strident, with far-fetched similes and repeatedly gruesome in-your-face details. After so many pages describing emaciated bodies and extreme physical torment, some readers will wish the author had understood that “less is more”; and they may also think there is undue reliance on stereotypes: the Australians are too Australian in their laconic bravery and mateyness, the Englishmen too class-bound, the Japanese too shrilly and insanely Japanese. Perhaps credible, but too loud in the telling. Yes, yes, we get it!

Flanagan’s novel has been flayed almost as often as it has been praised. Tony Abbott’s foolish intervention in the decision-making for the PM’s Literary Award provoked one of the prize judges, Les Murray, to break confidentiality and announce publicly that most of the panel members thought The Narrow Road “a stupid, pretentious book.” Less succinctly scathing but just as fierce was . Among the novel’s many faults, says Hofmann, is that “the writing is overstuffed, and leaks sawdust.” Phrases such as “sham texture,” “sticky collage” and “descriptive cant” run through this review, which sees Flanagan’s prose as parading a show of tender sensitivity, full of romantic clichés.

Susan Lever’s discussion of this novel in the Sydney Review of Books is less dismissive, but still expresses “unease” at the book’s insistent “literariness” in representing vicariously a generation of war veterans whose experience “is now receding into the past.” Lever concludes by describing it as “a work of filial and national piety.” That’s a shrewd comment, putting a finger on the obvious source of the novel’s emotional investment – and what some see as its sentimental excess. The Narrow Road to the Deep North is dedicated to the author’s father, a survivor of Japanese POW camps, and with understandable feeling Flanagan himself has spoken in interviews of growing up as a “child of the Death Railway.” This work, then, is an expression of “postmemory” in Hirsch’s sense: its focus is on “the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before.”

Steven Carroll’s A World of Other People has also come in for censure as too strained in its romantic gestures (What does that cover image on the left tell you?), too self-consciously literary, and “in no way convincing.” That verdict is by Andrew Fuhrmann, writing in the Sydney Review of Books. He describes the novel as “a somewhat bland story of doomed love” with “a romantic feebleness to the psychological mechanism.”

To judge by comments on this novel to be found on the Goodreads website, some readers think Carroll’s writing too often draws attention to itself. For example, in paragraph after paragraph nearly all the sentences are so short that the result can look like a kind of stylistic stammer, awkward and unproductive, yet with a portentous air. Here’s a random example:

You had to be watching to notice and Iris was. The statue has moved.

As she pieces the movements together – the shoulders, the hands, the eyes – she realises what they signal. The statue has not only moved. The statue, she realizes with astonishment, is crying.

She was about to leave. But she can’t now. Not while the statue is crying. Absurd as it may seem, she feels implicated. Responsible in some way. She has been watching him, studying him, all this time. Fascinated by the immobility, the stillness of the young man, and drawn to the waves of intensity radiating from him. Almost willing him to break. And now that he has broken she can’t go. Bronze and marble have melted into life.

So she waits.

There are other difficulties for a lot of readers. The way in which this novel uses T.S. Eliot’s poem Little Gidding as a framing device can seem contrived and fail to carry conviction. Arguably, Eliot’s presence as a character in the story feels awkward: he is “stiffly drawn” and other characters are “cardboard.” Those comments, too, are from the review by Fuhrmann, who adds: “it is hard not to wish the whole thing had been done without dragging in Eliot.”

These resistant readers of the Carroll and Flanagan novels remind me of John Keats’s remark in a famous letter 200 years ago: “We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us.” (For him and his contemporaries, the term “poetry” could apply to imaginative literature in general, including fiction.) Many of us feel, as Keats did, an antipathy to literary works that are too stridently insistent on commanding our attention. In the same letter, Keats says this:

Poetry should be great & unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze it with itself but with its subject.—How beautiful are the retired flowers! how would they lose their beauty were they to throng into the highway crying out, Admire me I am a violet! Dote upon me I am a primrose!

If you’ve read any of those novels and have a different opinion, tell me.

The post The War’s Not Over Yet: instalment 2 appeared first on Reid on Writing.

May 13, 2015

The War’s Not Over Yet: instalment 1

Seventy years after World War 2 ended, there continues to be a flood of literary works about it. Many are novels, but there are also beautifully written memoirs and biographies. In recent months I’ve been reading several books set mostly or wholly in that wartime period, and I’ll share a few of my thoughts about them here.

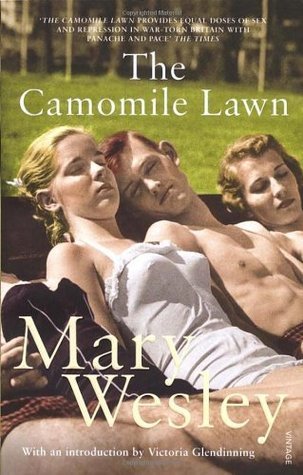

Most of the authors were born quite a while after those years of global conflict. An exception is Mary Wesley. This remarkable writer was already 71 when her first novel appeared in 1983, half a dozen more being published subsequently. The action of The Camomile Lawn centres on the late 1930s and early 40s in southern England. It’s clear from a biography of Wesley (Wild Mary, by Patrick Marnham) that this novel draws on her own experiences as a promiscuous young woman during those years, and perhaps it’s significant that the story she tells doesn’t get submerged in suffering, unlike so many books written about the war by those who weren’t there (and perhaps feel guilty about being belated). Mainly ironic in tone, and even comic at times, The Camomile Lawn is a startlingly frank portrait of an upper-middle-class English family and their sexual antics against a muffled background of international conflict. Especially noteworthy is the pace of the writing: I admire Wesley’s cleverly economical use of dialogue to depict character and move the story along.

The other books I want to mention (some here, some in a sequel post) are darker in tone, and come from a later generation than Mary Wesley’s. All have been produced in the last few years. Often the authors are retrieving and pondering the traumatic experiences of parents, grandparents or other older relatives, even when the genre is notionally fictional. Their writing seems driven by a desire to expiate or exorcise – or simply to ensure that some family memories are not forgotten. Marianne Hirsch has coined the word “postmemory” to describe “the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before – to experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up.” The following narratives are products of this “generation after.”

Alison Pick’s novel Far to Go, long-listed for the Booker in 2011, evokes the increasingly tense atmosphere in Czechoslovakia as the Nazis moved into Sudetenland, with betrayals disrupting civilian life. Although there were a few striking passages, I didn’t find it particularly impressive as a shaped work of fiction; some laboriously contrived imagery was a distraction, the layered method of telling the story struck me as unconvincing, and the characterisation seemed sketchy. What seemed to be the intended high point – the “Kindertransport” whereby thousands of Jewish children were rescued and taken to Britain just before and after the outbreak of war – lacked imaginative insight, coming across as an anti-climax. Far to Go has already begun to fade from my mind, in contrast to another novel set in the same place and time, Simon Mawer’s The Glass Room – which I read some years ago but still remember clearly, though I know it’s one of those books that readers tend either to love or to hate. Returning to Pick’s novel: the framing material indicates that this is a fictionalised version of things that the author’s grandparents experienced. The impulse to produce a kind of family testimony is understandable, but that in itself doesn’t make it successful as a work of fiction.

Alison Pick’s novel Far to Go, long-listed for the Booker in 2011, evokes the increasingly tense atmosphere in Czechoslovakia as the Nazis moved into Sudetenland, with betrayals disrupting civilian life. Although there were a few striking passages, I didn’t find it particularly impressive as a shaped work of fiction; some laboriously contrived imagery was a distraction, the layered method of telling the story struck me as unconvincing, and the characterisation seemed sketchy. What seemed to be the intended high point – the “Kindertransport” whereby thousands of Jewish children were rescued and taken to Britain just before and after the outbreak of war – lacked imaginative insight, coming across as an anti-climax. Far to Go has already begun to fade from my mind, in contrast to another novel set in the same place and time, Simon Mawer’s The Glass Room – which I read some years ago but still remember clearly, though I know it’s one of those books that readers tend either to love or to hate. Returning to Pick’s novel: the framing material indicates that this is a fictionalised version of things that the author’s grandparents experienced. The impulse to produce a kind of family testimony is understandable, but that in itself doesn’t make it successful as a work of fiction.

Miranda Richmond Mouillot’s memoir A Fifty-Year Silence is, for me, much more satisfying than Alison Pick’s novel. Despite their generic differences the two books have enough in common to invite comparison: Mouillot’s story is about her Jewish grandparents and their efforts to escape the Nazis – in this case from occupied France. But more than that, it’s about the author’s attempts to piece together the elusive tale of what really happened to them at that time and why their relationship subsequently fractured, resulting in a long and bitter estrangement. Also interwoven through that narrative of patient detection is Mouillot’s account of her own latter-day return to France, through which she eventually redeems what her grandparents almost lost. It’s written with a deceptively light touch, but I found it perceptive and moving. Both grandparents emerge vividly as flawed yet in some ways admirable figures, whose painful divergence is rendered with affection and empathetic respect.

Miranda Richmond Mouillot’s memoir A Fifty-Year Silence is, for me, much more satisfying than Alison Pick’s novel. Despite their generic differences the two books have enough in common to invite comparison: Mouillot’s story is about her Jewish grandparents and their efforts to escape the Nazis – in this case from occupied France. But more than that, it’s about the author’s attempts to piece together the elusive tale of what really happened to them at that time and why their relationship subsequently fractured, resulting in a long and bitter estrangement. Also interwoven through that narrative of patient detection is Mouillot’s account of her own latter-day return to France, through which she eventually redeems what her grandparents almost lost. It’s written with a deceptively light touch, but I found it perceptive and moving. Both grandparents emerge vividly as flawed yet in some ways admirable figures, whose painful divergence is rendered with affection and empathetic respect.

During her session at the recent Perth Writers Festival, Mouillot mentioned that she had initially tried to cast the story as fiction – and there are still several passages in which she imagines details of scene setting and interaction. This brings to mind Marianne Hirsch’s remark that “postmemory’s connection to the past is actually mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation.” But the focus of A Fifty-Year Silence is scrupulously factual: Mouillot resists the temptation to turn the untidiness of actual events into the beguiling shapes of romance. Her book shows convincingly that if a writer wants to bear witness to the wartime tribulations of family elders, it may be best to keep the truth in an unvarnished condition.

Nicholas Shakespeare’s Priscilla: The Hidden Life of an Englishwoman in Wartime France is another absorbing stranger-than-fiction family story from that period. Priscilla was the author’s aunt – a somewhat aloof figure in her declining years, holding her secrets tight. This fascinating biography takes great pains to uncover her astonishingly chequered career, and in the process paints a sombre picture of urban and rural life during the Vichy regime, from the privations of foreigners held in detention camps to the nefarious activities of the black market. Shakespeare’s persistence and skill (along with some good luck) in researching his aunt’s numerous relationships has produced many insights into the moral climate of the time; I was reminded at times of Wesley’s characters in The Camomile Lawn. The author makes this memorable comment on the process of delving into past events:

Nicholas Shakespeare’s Priscilla: The Hidden Life of an Englishwoman in Wartime France is another absorbing stranger-than-fiction family story from that period. Priscilla was the author’s aunt – a somewhat aloof figure in her declining years, holding her secrets tight. This fascinating biography takes great pains to uncover her astonishingly chequered career, and in the process paints a sombre picture of urban and rural life during the Vichy regime, from the privations of foreigners held in detention camps to the nefarious activities of the black market. Shakespeare’s persistence and skill (along with some good luck) in researching his aunt’s numerous relationships has produced many insights into the moral climate of the time; I was reminded at times of Wesley’s characters in The Camomile Lawn. The author makes this memorable comment on the process of delving into past events:

So much of research involves combing for wayward threads. Most of the time you pluck and what comes away is fluff. Just occasionally, as in fishing, the line goes taut and you feel a tug like a submerged handshake.

In a sequel to this post, I’ll comment next time on three recent wartime novels, all highly acclaimed (though only one appealed strongly to me), none of which could have been written without extensive research: Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Steven Carroll’s A World of Other People.

The post The War’s Not Over Yet: instalment 1 appeared first on Reid on Writing.

April 29, 2015

History’s Grist and Fiction’s Mill

Libraries are a valuable resource for any writer – and research libraries are vital for a writer of historical fiction. So imagine my delight at the news that I’ve been awarded the J.S. Battye Memorial Fellowship for 2015.

James Sykes Battye, Chief Librarian, State Library of Western Australia,1894-1954

The Battye Library, as many readers of this blog will know, comprises a wonderful assortment of archival riches within the State Library of Western Australia (SLWA). The purpose of the Battye Fellowship is to support projects that will enhance understanding of this State through research based on the Battye collections.

Over the next few months I’ll spend a lot of time happily immersed in those collections with the aim of producing a substantial piece of work on the process of writing historical fiction. I’ll present a public lecture on this topic, and the finished outcome – an illustrated essay – will eventually be published on the SLWA website and/or in print.

Fiction-writers who incorporate imaginary characters and episodes within a factual framework from times past are often asked what they are trying to achieve. This recurrent question incorporates others. What constraints, challenges and opportunities should such a writer recognise? Why include invented content anyway? Why not stick to facts? If a narrative goes beyond the discipline of pure history, what research protocols are necessary to convey a credible sense of authenticity?

In exploring such questions through this generous Fellowship, I hope to increase public awareness of how diverse and deep the Battye resources are, and how relevant they can be not just to history specialists but to a broader range of writers and readers as well. Many who use historical resources, or might be encouraged to use them, are not professional historians. I want to show how the Battye’s documentary and pictorial collections serve a wider literary community.

Various Battye collections are well known to me. As a writer specialising in stories about Western Australia’s past, I’ve made grateful use of the Library’s holdings of early photographs, newspapers, private archives, ephemera, maps and various official records. Some of these were especially useful in the groundwork for my forthcoming novel The Mind’s Own Place, which incorporates a range of events, places and personages from the colonial period in Western Australia.

My project’s title is ‘History’s Grist and Fiction’s Mill: researching and amplifying stories of Western Australia.’ This alludes to a paradigm case of blending archival research with creative writing: the Old Mill in South Perth, which figures substantially in The Mind’s Own Place. Using as a point of departure the Battye Library’s treasure trove of material on the Old Mill, I’ll develop an illustrated essay on the process of writing serious historical fiction. I’ll draw not only on my own experience but also on the work of several other novelists to discuss a range of examples of research-based historical fiction set in Western Australia, clarifying similarities and differences between pure and fictionalised history.

I can hardly wait to get on with it. And perhaps I’ll glimpse in some shadowy corner of the library a ghostly trace of its venerable namesake, James Sykes Battye, inaugural Chief Librarian, who began shepherding the State Library in the 19th century and continued in that role until the second half of the 20th. Now that’s a career of substance!

The post History’s Grist and Fiction’s Mill appeared first on Reid on Writing.

April 15, 2015

Inventing Literary Classics

Attention quiz-masters! Can you name the innovative book designer and printer who was the very first to publish a series of portable classics? Clue: he died exactly half a millennium ago.

In my recent post What is a Literary Classic? I mentioned several influential sets of books re-issued with a “classic” publication branding – Penguin Classics, Signet Classics, Virago Modern Classics, Classic Comics and so on. This kind of designation gives books a certain status – not an unquestionable status, but one that does carry some weight with most readers, at least subliminally.

Aldine publishing device, from the Great Hall ceiling, Library of Congress

Well, the idea of producing a publication series that makes classic texts available in a convenient format is far from new. It goes back to a period only a few decades after Gutenberg’s introduction of movable type to Europe. The process of inventing literary classics followed closely on the invention of the printing press.

The entrepreneurial Renaissance humanist who deserves the credit for inventing literary classics was Aldus Manutius (1449-1515), whose Aldine Press in Venice not only devised various innovations in typography (e.g. italics and semi-colons) but also created for the first time a series of inexpensive pocket editions of texts from Greek and Roman antiquity (Aristotle, Plato, Sophocles, Herodotus, Virgil, Ovid, Cicero…) along with Italian poetic masterpieces by writers such as Dante and Petrarch. An extraordinary accomplishment!

Portable, fairly compact – but those Aldine Press books didn’t look cheap. A great deal of care and professional expertise went into their design and production.

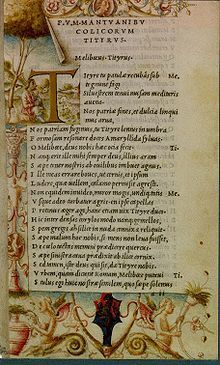

From Rylands Library copy of the Aldine Virgil (1501)

Fonts were selected for their aesthetic appeal, and sometimes created in-house. Several modern typefaces derive from those commissioned by Aldus and cut by his employee Francesco Griffo – among them Bembo, named after one of his contemporaries, the Italian literary scholar Pietro Bembo, whose work Aldus published. (I was delighted to discover the origin of Bembo, an elegant font used for two of my novels - That Untravelled World and the one forthcoming soon, The Mind’s Own Place.)

What’s more, elaborate and colourful illustrations often accompanied the printed text, as in this pictured example: a page from the Aldine Press edition of Virgil’s works. It was the first publication to use italic type, and the first in octavo format.

The significance of Aldus Manutius’s place in cultural history goes beyond his enterprising and skilful work as a book designer and printer. He was an admirable scholarly teacher, epitomising the Renaissance spirit – and in fact his reason for setting up a printing house was that he saw a need for students to have access to classic texts in a convenient format.

Alberto Manguel remarks in his book A History of Reading that Aldus’s home in Venice became a gathering point for eminent humanists from all over Europe, such as the Dutch luminary Erasmus. Together these men would discuss what classic titles should be printed and which manuscripts were the most reliable sources. Manguel records this moving final tribute:

When Aldus died in 1515, the humanists who attended his funeral erected all around his coffin, like erudite sentinels, the books he had so lovingly chosen to print.

The post Inventing Literary Classics appeared first on Reid on Writing.

April 1, 2015

What is a Literary Classic?

A classic, said Mark Twain impishly, is something we all want to have read but nobody wants to read. While many book-lovers can never quite find the time to work their way through War and Peace, Paradise Lost, Crime and Punishment or The Divine Comedy, most of us still harbour the idea that there’s a fairly well recognised western literary canon comprising an array of durable masterpieces. Even if we accept the theoretical point that a book’s traditional reputation doesn’t simply reflect its inherent merits, we like to think that certain books have earned a classic status. Where does this notion come from?

Italo Calvino remarks that each of us through our individual reading trajectories will gradually “invent our own ideal libraries of classics.” No doubt that’s true. But for most readers, in our most impressionable years, publishers’ branding is the main source of the notion that some books deserve special prestige. Things may have changed in recent times as the publishing industry evolves, but when I was a teenager, trying to get a handle on what constituted Great Literature, my perception was largely shaped by several series of books that carried the label “Classic.”

There was, for example, the World’s Classics library of pocket-sized hardbacks from Oxford University Press – what could seem more authoritative than that? Other influential lines from British publishers were Penguin Modern Classics (I still have my battered copy of Joyce’s Dubliners in that format), Dent’s Everyman Library (where I met Pater’s Marius the Epicurean and Woolf’s To the Lighthouse) and a bit later Virago Modern Classics devoted to women writers. American publishers offered Signet Classics (I first read Dickens’s Hard Times in that paperback edition), Bantam Literature (including Melville’s Moby Dick – a bantam whale?), Random House’s Modern Library Giants (introducing me to James’s Portrait of a Lady) and books in the Rinehart series such as Fenimore Cooper’s Deerslayer and Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

Many titles recurred across these lists, so with a number of different publishers agreeing that X was worth inclusion among their selected classics, who was I to doubt its status?

And besides, the process of instructing me in what was classic had begun earlier – before I’d opened any of those books. It began with the pictorial adaptations known as Classic Comics (later as Classics Illustrated). These had been appearing since 1941 but they were still flourishing when I was a youngster, and I devoured them.

And besides, the process of instructing me in what was classic had begun earlier – before I’d opened any of those books. It began with the pictorial adaptations known as Classic Comics (later as Classics Illustrated). These had been appearing since 1941 but they were still flourishing when I was a youngster, and I devoured them.

In those days there was a lot of harrumphing about the reading of comics, with dire forecasts that they would lead to a rapid decline in literacy. Well, I don’t think I was harmed by Walt Disney or Batman comics – and certainly not by Classic Comics, which not only made me aware of wonderful stories from times past, among them such masterpieces as Wuthering Heights and The Woman in White, but also gave me a burning desire to read them eventually in their full big-book form.

There’s something else, too, that I remember happily from those days of comic-book reading. As none of us had much pocket money, the pleasures of reading were inseparable from the rituals of exchange: when we’d read our comics, we swapped them for other comics in a system of bartering with friends. So we didn’t read in isolation, like Robinson Crusoe. We were reading in a context of active sociability. Perhaps it was that experience that first sparked my interest in the complex relationships between swapping and storytelling – which eventually led to my venture into literary theory with the (recently reissued) book Narrative Exchanges. I have a lot to be grateful for when I recall Classic Comics.

There’s something else, too, that I remember happily from those days of comic-book reading. As none of us had much pocket money, the pleasures of reading were inseparable from the rituals of exchange: when we’d read our comics, we swapped them for other comics in a system of bartering with friends. So we didn’t read in isolation, like Robinson Crusoe. We were reading in a context of active sociability. Perhaps it was that experience that first sparked my interest in the complex relationships between swapping and storytelling – which eventually led to my venture into literary theory with the (recently reissued) book Narrative Exchanges. I have a lot to be grateful for when I recall Classic Comics.

The post What is a Literary Classic? appeared first on Reid on Writing.

March 18, 2015

Is a book in the hand worth two in the ether?

Perhaps you do some or all of your book reading on an electronic device like a Kindle or i-pad. Conversely you may be someone who was never tempted to go digital in your reading. Or someone who tried an e-reader for a while but then discarded it in favour of that old familiar sensation of holding a book in the hand.

Most readers, even those of us who welcome the occasional convenience of e-books when travelling, say there’s no substitute for being able to handle a tangible object with covers, with a spine, with printed pages that can actually be fingered and turned. It’s a tactile pleasure worth cherishing – like stroking a cat.

What do writers think about e-books? As you’d expect, there’s some ambivalence. A recent online survey conducted for the Australian Society of Authors by a Macquarie University group (David Throsby et al.) probed authors’ opinions about the changing book industry, including e-books. A variety of views has emerged, of course, partly because authors’ experiences with e-books differ considerably according to the genre in question: sales in digital format tend to be higher for romance, travel, and ‘action’ stories than for literary fiction or young adult fiction. A shortage of reliable data complicates the picture, but many writers are troubled by the fact that the price of e-books keeps going down and therefore royalty returns are small except for self-published titles, where most of the income goes straight to the author.

Of course I’m very glad my novels are available in e-book format for those who prefer that medium – just as I’m glad that a couple of them have also been turned into audiobooks.

Nevertheless I don’t mind confessing that I still regard the traditional printed version (whether of my own publications or of those by other authors) as the Real Thing.

Why is this?

Well, part of it may be just an attachment to long-established reading habits, but there are a few practical reasons that go beyond simple nostalgia.

Unlike a text that’s stored electronically, a physical book may be chanced upon among other books in a shop or library, picked up and browsed through. For me this has often led to serendipitous discoveries.

It may be appreciated for its material properties – its size and shape, its weight in your hand, the texture of the paper it’s printed on, the particular look and feel of a well-bound hardback cover and its dust-jacket garb.

It may be wrapped and presented as a gift. There could hardly be a similarly ceremonial transaction with an e-book.

It may be autographed by the author, perhaps with an accompanying personal inscription. In a previous post I wrote about the value attached to signed copies.

It may be annotated with a reader’s thoughts. Usually it’s irritating to open a library book and find someone’s far-from-discerning scribble in the margins; but in rare cases a previous reader’s comments can illuminate a passage, providing much the same interest as an intelligent conversational exchange.

It may be preserved because of its personal associations, e.g. a beloved school prize or a battered old textbook from student days.

It may be taken down occasionally from your shelf, re-read, and placed back in a different spot so that it rubs shoulders with a new set of literary companions.

It may be passed on to other readers as a loan or a present or a charitable donation. I buy a lot of books and don’t have room to keep them all, so in the past few years I’ve given away thousands of them – many to universities (including a special collection of rare items donated to the Flinders University Library) or to charity shops.

It may be handed down within a family. Recently Natasha Robinson wrote about this for The Weekend Australian - about how much she treasures certain books read to her as a child, which were never discarded:

My mother kept some of our childhood books. John Brown and the Midnight Cat was a favourite… Now I read that story to my children. The pages are tattered; more than a few are held together with sticky tape. But it’s a physical marker of a tradition, of a head resting in the nook of a mother’s arm after bath time, a time of absorption that is all too rare in this electronic world. Long may it live.

The post Is a book in the hand worth two in the ether? appeared first on Reid on Writing.

March 4, 2015

The Book Pirates

In my distant boyhood, Stevenson’s Treasure Island and other stories about pirates captivated me and became part of my fantasy world.

In my distant boyhood, Stevenson’s Treasure Island and other stories about pirates captivated me and became part of my fantasy world.

I still have a well-thumbed birthday present from those days, Pringle’s Jolly Roger – an historical account of ‘the Great Age of Piracy’. My own earliest surviving story, written when I was eight and proudly typed by my aunt, involved a suburban boy’s nocturnal skirmish with a gang of swashbuckling sea dogs.

I didn’t expect that I’d eventually encounter any pirates in real life, but that’s what has now happened. Some of my writing has been pirated!

One might think that ebooks are the most common target for rip-off predators in the world of books. A recent post on the goodereader blog estimates that within three years there will be 700 million pirated ebooks. Yet the publishing industry in general is reportedly not much troubled by this. Big publishers regard ebook piracy as a minor nuisance that has little impact on sales. They seem confident that their Digital Rights Management solutions are working well enough.

However, I’ve run into a different problem: international piracy of printed books through unlicensed translations.

My little book The Short Story, published many years ago in Methuen’s ‘Critical Idiom’ series, has sold about 20,000 copies in English and I’ve also received due recompense for authorised translations into Greek, Korean and Bahasa Malay.

I’ve since discovered that, in addition, the book has appeared in two other foreign languages: Mandarin Chinese and Farsi (Persian). The first of these came to my attention because a Chinese literary scholar made contact with me when writing an article about my work. I found out about the Farsi edition through the goodreads website. According to Taylor and Francis (the owner of Methuen titles), neither of those translations was licensed, which is why I’ve never received a cent for them. T&F are still trying to track down the Chinese publisher, but the prospect of obtaining any financial return from the Farsi edition is not hopeful because Britain (where T&F is based) has a total trade ban with Iran. This means that British publishers are unable to sell books to Iran and cannot issue licences or enter into correspondence regarding translations. Only when (if ever) this sanction is lifted can T&F make contact with the Iranian publisher to seek reparation.

Meanwhile it seems my book has undergone a not-so-jolly rogering! Am I singularly unfortunate? Does anyone out there know of other comparable experiences with copyright infringement by book pirates?

The post The Book Pirates appeared first on Reid on Writing.

February 15, 2015

Blytonians come out!

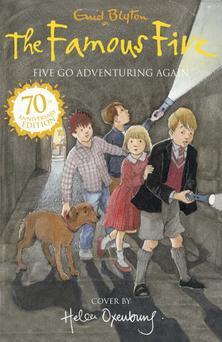

Dead for nearly half a century, yet her books still sell eight million copies a year in more than 90 languages! You’d think that such a writer deserves to be hugely admired by literary commentators and educators. On the contrary, her work often encounters stern censure – and even censorship: some public and school libraries refuse to hold copies of any of her books.

Yes, I’m referring to Enid Blyton. Her stories for children continue to come under fire, and in some respects the target is an easy one. Their language is generally formulaic and they tend to represent gender, class and race stereotypically. One critique describes her writing style as ‘colourless, dead and totally undemanding’ and scorns her main theme as ‘an insistence on conformity.’

Then why is Enid Blyton remembered gratefully (albeit with a touch of embarrassment) by a large number of grown-ups? I’ll come to my own confession soon, but I’m far from alone in acknowledging that her books beguiled me. Six years ago, in a survey of 2000 adults, Blyton was voted Britain’s best-loved writer, ahead of (in descending order), Roald Dahl, J.K. Rowling, Austen, Shakespeare, Dickens, Tolkien, Agatha Christie, Stephen King and Beatrix Potter.

If that surprises you, consider the surge of recent tributes from respected Australian writers. A few weeks ago Robert Drewe began one of his columns in the West Weekend with these words: ‘Like millions of other 20th century kids, I grew up in the literary worlds of Captain W.E. Johns, Richmal Crompton and, most of all, Enid Blyton.’ The main attraction of Blyton’s books, he says, ‘was that the children were much cleverer than the adults, especially the police, at solving crimes (which often involved smugglers), and very much in charge of their lives.’

Robert Dessaix’s latest book, What Days Are For, includes this declaration: ‘Enid Blyton, and Five on Kirrin Island Again in particular, shaped me in a way no other writer or book ever did, with the possible exception of Richmal Crompton and her William stories.’ Why? Dessaix puts his finger on what it was in those stories that moulded his imagination: ‘the subtext: the idea of loyalty to your close friends no matter what, the sharing of secrets with them (an important part of growing up), and also the unusual gendering…’ There was something more, too: ‘Exploration in Blyton’s world is…at the heart of any adventure.’

Is this just a boy thing? Not so. Amanda Curtin mentions in an interview that as a young reader she ‘was always keen on series books, like Enid Blyton’s Famous Five and Secret Seven and Malory Towers sets.’ And Kate Forsyth’s voice joins the chorus: ‘For quite a few years, nothing gave me such a thrill as being given a new Famous Five book…I daydreamed about exploring secret passages, thwarting smugglers, discovering buried treasure and having a dog called Timmy. My sister and I used to fight over who would get to be George, the girl-who-was-as-good-as-a-boy.’ She adds: ‘confessing to all this is actually quite hard’ because ‘Blyton has been sneered at for so many years…If one wants to be taken seriously, one does not admit to a childish love of Enid Blyton.’

Well, I want to be taken seriously too – and my own experience was much the same. Although there weren’t many books at home during my primary school years, the local shopping precinct included a small commercial lending library, and I went there often with the same query: ‘Any new Enid Blyton or William books?’ (My Biggles phase came a bit later.) There always seemed to be something new from Blyton’s pen; the Famous Five series alone ran to over a score of titles. In those pre-decimal days the price was just fourpence a loan. The library was next door to the barber shop where I’d get a short-back-and-sides haircut for ninepence while staring –‘Keep your head still, lad’ – at the mysterious inscription on the adjustable chair’s metal footrest: REG US PAT OFF. It took me years to decipher that message, despite being trained in code-reading by Blyton’s books.

I had two Blyton phases. The later one, in my pubescent years, focused predictably on the Famous Five and the Secret Seven, and it generated feeble pastiche stories. (I still have a copy of the exercise book in which I wrote Four Go Off to Camp – not an enduring masterpiece, though probably no worse than the efforts of an average 9-year-old imitator. Ah, if only I’d been alert at that age to the sensational narrative potential of a camp adventure on Shag Island!)

But I think the earlier phase, my kiddy phase, revealed something deeper and more surprising: Blyton’s seldom-noticed capacity to produce unforgettable images that could haunt a young mind. When I was seven years old my parents bought me a subscription to Blyton’s magazine Sunny Stories, and I remember the thrill when issues arrived in our letter-box. (Those were the days when an ‘issue’ was just an instalment of a publication, not a ubiquitous fuzzy euphemism for a big personal problem, as in ‘Yet another AFL footballer has an anger management issue.’)

One scene from one story in one issue of Sunny Stories still lingers behind my eyes. This wasn’t actually a ‘sunny’ story; it disturbed me. A Freudian analyst could probably explain why. It was about a boy who found that when he looked through a magic knothole in the wooden fence in his backyard he could see all the bad things he had done. I don’t remember anything else from the story, but that guilt-laden discovery was enough. No wonder I turned out to be a writer instead of leading a normal well-adjusted life. Looking through that scary knothole, I saw things I wouldn’t have seen otherwise.

In his fascinating memoir of youthful reading, The Child That Books Built, Francis Spufford remarks that ‘books did for us on the scale of our childhoods what the propagandists of the Enlightenment promised that all books could do for everyone, everywhere. They freed us from the limitations of having just one life with one point of view; they let us see beyond the horizons of our own circumstances.’

After quoting Hazlitt on the great value of reading in providing ‘a knowledge of things at a distance from us’, Spufford goes on to say:

Adjust for the fact that the book in question will be Blyton’s The Island of Adventure instead of Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature, and Hazlitt’s manifesto applies. The books you read as a child brought you sights you hadn’t seen yourself, scents you hadn’t smelled, sounds you hadn’t heard. They introduced you to people you hadn’t met, and helped you to sample ways of being that would never have occurred to you.

So let’s crack open a bottle of ginger pop and drink to Enid Blyton!

The post Blytonians come out! appeared first on Reid on Writing.

![The mind's own place_cover[1] copy_3](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1433669737i/15128692._SX540_.jpg)