Ian Reid's Blog, page 7

May 18, 2016

Why Monsieur Parizot made a fuss

Victor Parizot was refusing to pay his bill.

He hadn’t intended, on that evening in 1849, to create a scene at his local Parisian restaurant; the meal and musical entertainment were enjoyable. But when, to his surprise, the small orchestra played a particular piece of music with which he was thoroughly familiar, he decided to stand up for his rights. It was one of his own compositions and he thought he should be recompensed for its use. ‘I’ll pay for my dinner,’ he told the waiter, ‘when I’m paid for my music.’

The ensuing dispute went to court, where the composer won his case, thus establishing that the creator of a work of art deserves remuneration when it’s publicly used. A further century would pass before the principle of performing rights became extended to lending rights for authors whose books are borrowed from public libraries, and in our country Public Lending Right legislation was not enacted until 1985, after many years of dogged campaigning by the Australian Society of Authors (ASA). It almost happened a decade earlier: Gough Whitlam’s bill to provide an administrative framework for PLR was scheduled for tabling in parliament on 11 November 1975 – the day of his government’s dismissal.

The scheme of PLR payment to authors, based on the number of library loans of their books, is just one of the great achievements by the ASA since its foundation more than half a century ago. I’ve recently been reading Status and Sugar: A History of the Australian Society of Authors 1963-2013, by Stephany Steggall, in which I read about Monsieur Parizot’s dispute and many other instructive episodes from the past. As one who has benefited materially from PLR, from fees for licensed copying, and from several other business arrangements designed to protect writers, I have good reason to be deeply grateful to this fine organisation.

The scheme of PLR payment to authors, based on the number of library loans of their books, is just one of the great achievements by the ASA since its foundation more than half a century ago. I’ve recently been reading Status and Sugar: A History of the Australian Society of Authors 1963-2013, by Stephany Steggall, in which I read about Monsieur Parizot’s dispute and many other instructive episodes from the past. As one who has benefited materially from PLR, from fees for licensed copying, and from several other business arrangements designed to protect writers, I have good reason to be deeply grateful to this fine organisation.

Writers in Australia today face serious challenges, and need more than ever the advocacy and practical support provided by the ASA. Some of those challenges dominated discussion at the ASA’s Annual General Meeting held last weekend in Sydney, which I attended in my capacity as a newly appointed Director on its Board of Management. It was sobering to hear about the likely impact of recent developments such as the release of the Productivity Commission’s wrongheaded draft report on Australia’s intellectual property arrangements.

The so-called ‘Fair Use’ exception to existing copyright provisions, which the report recommends be introduced, would be culturally and economically damaging for Australia, and would rob individual authors of a legitimate source of income from copying fees. For a summary of problems that would ensue if this report were to be adopted by government, see what the Copyright Agency has to say.

The Commission also recommends the repeal of restrictions on the Parallel Importation on Books. This is a more complicated and contested topic. On the one hand it seems to some commentators that the current restrictions are anti-competitive, protecting local publishers at the expense of readers. But for a contrary view, see Thomas Keneally’s remarks in the Australian Financial Review.

You can expect vigorous public combat and private lobbying on these matters during the federal election campaign. And you can rely on the ASA to be in the thick of it. If you’re an established or aspiring writer but are not a member of the ASA, do consider joining so that you can contribute to and benefit from a vital organisation devoted to promoting and protecting the professional interests of literary creators. Its website contains information about different categories of membership and the various services provided.

The post Why Monsieur Parizot made a fuss appeared first on Reid on Writing.

May 4, 2016

Memory loss and retrieval

Any visitor to an aged-care home knows that chronic forgetfulness, in its extreme form, is severely disabling. Few things are sadder than the bewilderment of a person no longer able to make connected sense of a series of events, no longer able to bring past knowledge to bear on present situations. Losing the capacity to remember can eventually betoken dementia and the dissolution of individual identity.

Ironically, total recall is also disabling; and this phenomenon, though much less common, sheds light on the nature of memory. It’s the theme of ‘Funes the Memorious,’ a short story by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Because of a brain injury the character called Funes cannot forget any detail of what he perceives. He is cursed to carry all of it vividly in his head forever – an intolerable burden because he is entirely immersed in the accumulated particulars, unable to generalise or be selective, and therefore unable to interpret his world. So his prodigious aptitude is significantly different from memory, which sorts, arranges and weaves, creating a narrative structure through which experience acquires meaning.

What is true of individual identity is also true of social identity. Researchers working across disciplines have shown how personal and group memory become intertwined in a psychological process fundamental to history and culture. If a civilisation loses its memory, forgetting or repressing fundamental experiences that have collectively shaped it in the past, it will tend to fall apart; and if on the other hand it becomes submerged in a cumulative mass of information without being able to discern meaningful narrative patterns in it, that too will cause its collapse.

Mnemosyne, Greco-Roman mosaic, 2nd c. AD, Antakya Museum

Memory has a more central importance in culture and in learning than we sometimes recognise. Ancient Greek mythology provides an insight into this matter. Our word mnemonic comes from the goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, who had a pre-eminent cultural status: she was mother of the nine muses, including lyric and epic poetry, dance and music, tragedy and history. Seen as the inventor of language, Mnemosyne presided not only over writing but also over the practice of memorisation required to preserve stories in oral tradition.

With Mnemosyne in mind, I find myself at a point in life (probably not quite the end, perhaps not even the beginning of the end, but well past the end of the beginning) where I often look back over roads I have travelled along and forking paths that have made me hesitate. Occasionally this remembering may be regretful or nostalgic, but for the most part it draws me into inquisitive reflection. I think about the functioning of memory, about how it informs narrative linkages between personal or professional trajectories and the larger meandering history of fields of study – particularly about continuity and change in the subject called English. I recall pivotal moments in my working life, ponder conscious and unconscious decisions I made, trace the foreseen and unforeseen consequences of choosing this option rather than that. Back there in the past I see crooked lines of stepping stones (some seemed at the time to be obstacles) across which I made my stumbling way as a student, teacher, curriculum reformer, author. I glance over my shoulder at the different genres of the things I have written, trying to reconstruct a chain of circumstances that motivated me to produce those various books and articles and other items. Retrospection leads me to ask how I happened to wander into English teaching; why so much of my energy, over the decades, has been invested in language, literacy and literature; why I never confined my activities to one sector of education but kept engaging with schools as well as with universities; why I turned my productive efforts from poetry to polemics, from literary theory and cultural history to the writing of novels…

[The musings reproduced above are the opening paragraphs of an essay I was invited to contribute to the just-published issue (23.2) of the British educational journal Changing English.]

The post Memory loss and retrieval appeared first on Reid on Writing.

April 20, 2016

Like death at the door

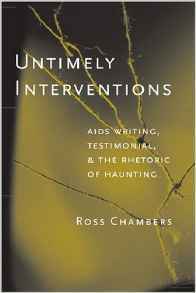

In his book Untimely Interventions, the venerable Australian-born and USA-based literary theorist Ross Chambers (one of my mentors) discusses what he calls testimonial writing. He defines this as an edgy form of literature that bears witness to historical traumas, calling the dead to life and calling on the living not to forget them. Its subject matter can be any painful episode in modern social history that’s hard to confront, ‘haunting the periphery of our safe and protected world like death at the door.’ Testimonial writing insists on remembering what it would be easier for us to repress. Chambers observes:

‘National cultures, these days, seem increasingly aware of the sense in which they are haunted, both by past atrocities and by the continuing injustices those atrocities have spawned.’

The examples he lists include Germany struggling to deal with its guilt over the Holocaust and with resurgent neo-fascism; France trying to lay the ghosts of its Vichy past; the USA living with the long aftermath of slavery and the Civil War; South Africa facing the legacy of apartheid; Israel confronting the realities of co-existence with displaced Palestinians; Australia and many other countries still dogged by the consequences of colonialism.

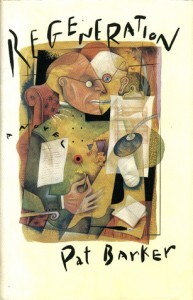

Remarking that ‘as the “original” witnesses and survivors age and die, new means of regenerating their witness will have to be found,’ Chambers discusses the instance of Pat Barker’s 1991 novel Regeneration, part of a trilogy set in England during the last year of World War 1. Its storyline testifies not only to the slaughter of huge numbers of soldiers on both sides, especially in trenches of the western front, but also to the difficulty of reporting back truthfully from the war zone to those in England. By incorporating episodes from the real-life wartime experiences of writers Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, and depicting their attempts to devise a new poetic idiom that would express without lyrical evasion the horror of this brutal conflict and its lingering aftermath, this novel evokes the condition of ‘perpetually surviving a trauma that is never over.’ Much of the action takes place in a hospital for shell-shocked officers, which becomes symbolic of Britain itself, physically isolated from the battlefront but haunted by its pain despite strenuous efforts to forget.

Remarking that ‘as the “original” witnesses and survivors age and die, new means of regenerating their witness will have to be found,’ Chambers discusses the instance of Pat Barker’s 1991 novel Regeneration, part of a trilogy set in England during the last year of World War 1. Its storyline testifies not only to the slaughter of huge numbers of soldiers on both sides, especially in trenches of the western front, but also to the difficulty of reporting back truthfully from the war zone to those in England. By incorporating episodes from the real-life wartime experiences of writers Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, and depicting their attempts to devise a new poetic idiom that would express without lyrical evasion the horror of this brutal conflict and its lingering aftermath, this novel evokes the condition of ‘perpetually surviving a trauma that is never over.’ Much of the action takes place in a hospital for shell-shocked officers, which becomes symbolic of Britain itself, physically isolated from the battlefront but haunted by its pain despite strenuous efforts to forget.

Chambers sees Pat Barker’s Regeneration as exemplifying the increasingly important role of historical fiction in ensuring we retain the kind of cultural memory that testifies to what humanity has suffered. This insight helps me to understand why in recent years I’ve devoted most of my energies as a writer to novels set in times past, especially to experiences of bitter hardship.

The post Like death at the door appeared first on Reid on Writing.

April 4, 2016

Beyond ‘Juvenile’ and ‘Young Adult’ Books

The quantity of books marketed as ‘Juvenile’ or ‘Young Adult’ (YA) Fiction seems larger than ever, but do these categories cater adequately for teenage readers? It’s a question worth posing in the light of three things I’ve just been reading: an accomplished novel, a remark by a champion of books for the young, and a reminiscence by Charles Dickens.

The quantity of books marketed as ‘Juvenile’ or ‘Young Adult’ (YA) Fiction seems larger than ever, but do these categories cater adequately for teenage readers? It’s a question worth posing in the light of three things I’ve just been reading: an accomplished novel, a remark by a champion of books for the young, and a reminiscence by Charles Dickens.

Duncan Mackay’s Storm Callers (Fremantle Press) appealed to me when it came out in 2007 and still seems a fine example of what a skilled writer can achieve within the framework of Juvenile or YA fiction. Its two main characters, on the brink of high school, meet in a beachside caravan park during their summer holidays, and make some discoveries together – including discoveries about themselves.

Picking up my copy of the book again after a few years, I found tucked inside it a printout of my email exchange with the author, in which I’d tried to convey what particular qualities I appreciated. As a re-reading hasn’t changed my mind, I’ll summarise here some of the things I said to Duncan about those first impressions – and then I want to step back from this particular book and reflect generally on the kinds of reading that I regard as valuable for teenage readers.

The structure of Storm Callers creates a strong momentum: it begins in an engaging way and moves to a satisfying ending. (More about the ending shortly.) The characters are convincing, too. They evoke memories (distant in my case!) of what it’s like to be pubescent – the surge and ebb of enthusiasms, all the social awkwardness, the impulsive fabrications, the flaring and fading of friendships. The language is entirely appropriate, successfully managing the considerable stylistic challenge of filtering everything through the consciousness of a not-very-articulate boy.

What I found especially impressive was the tactful manner in which the story’s implications are lifted to a level above the prosaic. Mythological allusions are introduced without strain. It’s risky for the author of a realistic tale about adolescents in our time and place to refer not only to classical deities but also to biblical motifs, but Storm Callers does so quite convincingly, gesturing towards an archetypal theme – attaining knowledge of good and evil. This culminates in a movingly understated conclusion, with the final sentence faintly echoing phrases in the final lines of Milton’s Paradise Lost.

While revisiting Duncan Mackay’s book I was also prompted to think about the broad category of fiction for adolescents and mature children because I came across a not-very-recent online interview in which Monica Edinger discusses a book called A Family of Readers: The Book Lover’s Guide to Children’s and Young Adult Literature. She asks one of its editors, Roger Sutton, about his own early reading.

He says that from the age of about nine he read voraciously both adult books and children’s books, the great and the trashy alike. (That was true for me too, and probably for many who are reading this blog.) Sutton adds the following comment, which chimes with my own view:

I hope that today’s teen readers aren’t pushed away from adult books. While it is true that YA literature is wider and richer than ever before, it is largely restricted to coming-of-age themes, and sometimes you want to read about someone who has been there, done that, and moved on.

It’s illuminating, I suggest, to put that comment beside an eloquent reminiscence recorded by Charles Dickens. Dickens grew up as a sickly and neglected child in an impoverished family, but books enriched his imagination. His father had acquired a set of cheap reprints of prose-fiction classics, and young Charles read them avidly, as recorded in an autobiographical fragment on which he drew directly for a memorable passage in David Copperfield. David, exactly like his creator, devoured at a tender age the stories of Don Quixote, of the Arabian Nights, of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Fielding’s Tom Jones, and (in his words) ‘a glorious host’ of other writings. He goes on to describe how he went around his house impersonating his favourite characters and embarking with them on voyages to exotic destinations. What he says about the value of those imaginary excursions is simple and eloquent:

They kept alive my fancy, and my hope of something beyond that place and time.

Often in the world of present-day pubescent and adolescent readers there is too much that confines them narrowly within the preoccupations, ideas and idioms of their own here-and-now milieu. Certainly some stories that reflect everyday experiences and topical tribulations in which their teenage readers are already immersed may help to clarify what they feel, alleviate their worries, free their imaginations. But surely it’s at least equally important for those readers to encounter grown-up fiction that is not set in their own place and time, not holding up a mirror to what and where they are but opening a doorway into richly imagined worlds elsewhere.

The post Beyond ‘Juvenile’ and ‘Young Adult’ Books appeared first on Reid on Writing.

March 21, 2016

Books: a shrinking shelf life?

Books are getting more and more like loaves of bread.

Books are getting more and more like loaves of bread.

Bakers and bread-sellers ply their trade in an increasingly crowded market, where all sorts of shops offer all sorts of of doughy products in larger quantities than ever before. Compounding their challenge is the fact that bread soon goes too stale to attract consumers, so unsold loaves must be removed from the retailer’s shelf within a day or two of baking.

With books, too, the clear trend is for a greater number to be published each year, while the turnover rate accelerates and the number being bought decreases. (Actually there may have been a recent pause in the pattern of declining unit sales, but they are still well down from their peak.) So although a particular new book may seem, at least to its fond author, the best thing since sliced bread, its shelf life is likely to be just as pathetically brief. Book industry figures for publication and sales tell a discouraging story.

In 2014 (the most recent stats I’ve found) nearly 21,000 books of various kinds were published in Australia alone. That’s 400 each week! Though only a small proportion of these came from serious publishers producing multiple titles and using regular distribution channels, there’s no doubt that every link in the book chain from authors to readers is being overwhelmed by a glut.

A gigantic avalanche of loaves tumbling from bakery shelves? More like a publication tsunami. Taking a Darwinian view, you might think this swelling, swirling flood isn’t such a bad thing. Many books will sink, OK; but won’t the fittest still swim and survive?

It’s probably not so simple. Saturation of the book market makes it harder and harder for a diverse range of fine new books, even work by highly accomplished writers, to get reviewed on the diminishing literary pages of major media. Similarly there’s such intense competition for a place on other publicity platforms, like gigs at literary festivals, that many potentially important titles won’t get a look-in. More often than ever before, a marketing ploy can eclipse merit.

Sure, a few will be fortunate enough to receive a fanfare of awards and acclaim, yet the welcoming moment will quickly be forgotten as another huge dumping wave of publications arrives, then another and another. Most authors learn to be grateful if they just avoid drowning.

We’ve all heard the sardonic forecast, attributed to Andy Warhol, that in the future everyone will be famous – for 15 minutes each. Will this soon be the fate of even the most celebrated authors of the most successful books?

Against that sombre background, against the odds, it’s an occasion for rejoicing when a book shows some durability. There’s a special pleasure in seeing any of one’s publlications reissued after a lapse of years. I’m delighted that two of my critical studies will have their shelf life prolonged, decades after their first appearance. Narrative Exchanges, a work of literary theory that came out in 1992, has a new lease of life in the series ‘Routledge Revivals’, and I’ve just heard that my book on English teaching, The Making of Literature: Texts, Contexts and Classroom Practices, is soon to be made available in digital form 32 years after its print debut. The publisher, AATE (Australian Association for the Teaching of English), tells me the book is continuing to generate ‘quite a bit of interest’ internationally. Its reappearance will be timely, as I’ve been invited to give keynote addresses on topics related to this book’s themes at forthcoming conferences of English teachers both at the state level (ETAWA, in Perth this May) and national level (AATE, in Adelaide in July).

The post Books: a shrinking shelf life? appeared first on Reid on Writing.

March 7, 2016

Knowing by heart

Recently I read Dennis Haskell’s fine new poetry collection, Ahead of Us (to be launched tonight), a memorable book that has left a gritty residue in my mind.

Most of the poems, as they encircle the poet’s loss of his dead wife, evoke suffering and bereavement. Yet this pain-racked process is also a source of continual self-confirmation as he remembers and revaluates past times and places.

Going back as a widower to a Norwegian village that he first visited four decades earlier with her, he finds

there’s nothing here

beyond memories

that make me

what I am.

Bleak though they are, those simple lines resonate for me. I’ve been thinking lately about the extent to to which we shape our personal identity by making sense of our past and linking it to our present and future selves. I’ve also thought about the particular importance of this for writers.

Knowing ourselves is inseparable from the habit of conscious, intensive remembering, a valuable habit that featured strongly in my own childhood because it was reinforced by the practice (normal in those days) of requiring or encouraging children to learn poems and many other things verbatim.

In an earlier post I argued that although ‘rote learning’ is out of favour in schools it would be a mistake to neglect this way of fostering memory. Structured memorisation is not only an elementary basis for developing knowledge but also a potentially rich resource for advanced stages of reading and writing. Comments from writers and educators on my earlier post indicate that I’m not alone in this conviction.

Learning as a child to remember a patterned sequence of words and recite them in a group can be like a rudimentary form of choral singing – a source of delight rather than drudgery. And with maturity there may then come an internalised individual practice of memorisation, as we recognise the value in becoming so familiar with certain passages of verse or prose that we know them by heart. Knowing by heart is a mode of cognition to be cherished, not disparaged – especially in relation to the reading and writing of literature. Committing to memory what we read, far from being in conflict with creativity, can contribute substantially to it.

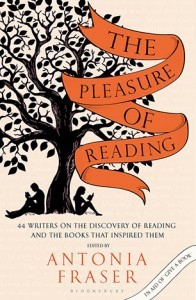

Recently I came across supportive evidence for this point in a book called The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (2015). Fraser brings together the reminiscences of numerous writers about what they read in childhood and how they read it. Many emphasise the value of early habits of memorising and reciting passages of poetry and prose. Here are just a few examples.

Recently I came across supportive evidence for this point in a book called The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (2015). Fraser brings together the reminiscences of numerous writers about what they read in childhood and how they read it. Many emphasise the value of early habits of memorising and reciting passages of poetry and prose. Here are just a few examples.

‘At home and at school there had been much learning by rote, both compulsory and by choice’, says the brilliant travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor – and he lists many literary works and excerpts, committed to memory as a boy, which he was able to recite to himself at length as he hiked alone across Europe at the age of 18. Melvyn Bragg comments on the formative importance of group chants, remarking that literary influences may have ‘more to do with rhythm than subject, with sound rather than sense, especially at the start, which is when influences most matter.’ Candia McWilliam remembers obsessively repeating patterns of strange phrases as she jumped over her skipping rope, progressing to nursery rhymes and then going on to learn many poems verbatim.

For Jeanette Winterson, being ‘brought up to memorise very long biblical passages’ as a child equipped her to learn and recite difficult poetry in her school years. When very young, Emily Berry came across a volume of grown-up verse; ‘many of the poems in it’, she says, ‘were over my head, but I discovered the calming practice of incantation and there were some I read aloud many times.’ ‘Verse speaking’, recalls Roger McGough, ‘played an important part in fashioning my reading…. Eventually, as I became unselfconscious about hearing my own voice, I learned to listen to the poet’s.’ Jan Morris mentions many books whose ‘words and tales and cadences’ became, she says, ‘irrevocably a part of me’, including one whose ‘stupendous style’ continues to ‘ring so permanently through my mind that to this day I sometimes sing its opening lines aloud in the bath.’

For these writers and many others, early practices of rote learning, chanting memorised passages, provided a store of rhythmic language from which they could later draw in shaping their own artful compositions. I’m glad to have learnt things in this way, and sad that countless young children today are deprived by neglectful teachers and parents of the pleasure that rote learning can bring.

The post Knowing by heart appeared first on Reid on Writing.

February 22, 2016

Empathy, memory, writing

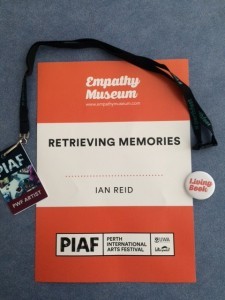

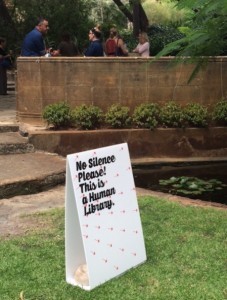

Storytelling nurtures empathy. I’ve considered the link between them in a previous post, and during last weekend’s Perth Writers Festival it was a recurrent theme, especially in the Human Library sessions organised by the UK-based Empathy Museum.

Storytelling nurtures empathy. I’ve considered the link between them in a previous post, and during last weekend’s Perth Writers Festival it was a recurrent theme, especially in the Human Library sessions organised by the UK-based Empathy Museum.

I took part in one of these as a “living book,” the arrangement being that several people, one at a time, sat down with me for a few minutes each in the calm open-air setting of a tiered sunken garden and listened to a brief tale that I told informally about myself. Then they asked questions, made comments, and we talked on until my interlocutor’s allotted time expired and it was someone else’s turn to borrow me from the bookshelf (so to speak).

The general topic for the session in which I participated was “Age.” I talked about this with particular reference to the role of memory in my writing life. Narrating something orally, face-to-face with a listener, can quickly establish an empathetic relationship, but the medium of print makes this more complicated.

Although I’ve been a full-time writer for only a few years, the practice of shaping words creatively into stories, poems, and other literary forms has been a large part of my life since childhood. What I wrote when I was 8, 9, 10, had no connection with anything I’d experienced myself. There were stories about expeditions to distant planets and to Borneo jungles; about encounters with smugglers and with castle ghosts; about the adventures of highwaymen and pirates. And there were poems describing landscapes drawn dreamily from books, not from observation. Nothing wrong with any of that; in the early stages of learning to deploy language imaginatively, the content didn’t matter much.

But with the passage of years my writing has turned away from the merely fanciful towards empathetic realism, and in the process it has become inseparable from my remembering – the retrieval not only of personal memories that are uniquely mine but also of cultural memories that are a shared resource.

One reason why I attach increasing importance to memory is that some significant patterns in my experience have only become legible in retrospect. Looking back, I see things I didn’t see at the time. Another reason is that people and places once influential in my life are gradually disappearing. Some friends and family members have dropped away into darkness, beyond reach except in memory. Even some of the physical environments in which I grew up are now in ruins. As earthquakes have pulverised Christchurch, where I spent my most formative years, the landmarks of childhood and youth survive only in my head and heart.

So my memories are increasingly valuable to me. Fragments from my past life occasionally find their way, transmuted, into what I write, infused with “emotion recollected in tranquility” (in Wordsworth’s phrase). And in a more extensive way I draw on memories that are not specifically my own but belong to bygone times. In recent years the focus of most of my writing has been on historical fiction. Why set my novels in the past? Because I want to retrieve certain historical realities that our contemporary culture has largely lost or repressed. I want to resuscitate the dead. I want to reveal things (often unpleasant things) that contributed to the contours of our own society, and keep them alive in cultural remembrance.

At its best, imaginary time travel through historical fiction is not an escapist withdrawal from pressing questions that confront us in our own world. Rather, it can show aspects of the present in a new light. For example, emotionally fraught migration stories dominate news reports, and it’s hard for us to step away from the headlines and images that dramatise the current plight of refugees, so that we can think about displacement as a recurrent and necessary feature of human history; but historical fiction can help us to understand this with a different kind of empathy. My first novel, The End of Longing, evokes the era when steamship and rail were rapidly opening up the world to ordinary travellers, and my third, The Mind’s Own Place, tells the linked stories of mid-19th-century migrants to Western Australia. Cross-national journeying takes many forms, with different meanings for those who undertake it voluntarily or involuntarily.

I’ve tried to show in my fiction that many such episodes are worth salvaging from oblivion because they provide not only cautionary tales and corrective reminders but also things to commemorate and cherish. I feel the same way about retrieving memories from the early decades of my own life and times.

The post Empathy, memory, writing appeared first on Reid on Writing.

February 8, 2016

Debut novelists – but hardly novices

A literary lion guards the NY Public Library

(source: Carol Highsmith – public domain)

As in previous years, this month’s Perth Writers Festival (PWF) will bring together assorted literary lions from several corners of the world and put them on platforms for three days of intensive talking. No doubt some will exceed expectations and some will disappoint. Not all authors turn out to be accomplished speakers, deep thinkers or charming personalities. Nevertheless this annual event continues to attract large audiences. What are they looking for?

Most people who scan the PWF program booklet with a view to attending at least a few sessions will hope to find not only a mixture of lively topics but also a good number of newcomers along with well-established writers. If the planners do their job well the big names will be balanced by relatively unfamiliar names. Although a festival such as this would seem incomplete without some literary lions, it’s also an occasion for emerging talents to join the parade.

The session I’ve been invited to chair (‘Reimagining’: Sun 21 Feb at 10am) will feature three writers whose first novels (all historical, based on real people and events) have recently appeared – yet none could be considered a novice storyteller.

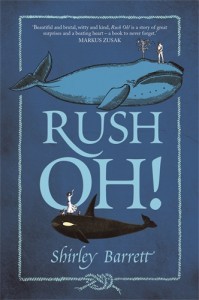

Two of them are Australians. Remarkably, both had already won significant national and international recognition before these books were published. Lucy Treloar, whose debut book is Salt Creek, was previously the winner of the Commonwealth Short Story Prize for the Pacific region. Shirley Barrett, author of Rush Oh!, has an enviable reputation as a screenwriter and director whose films have won awards not only in Australia but also at Cannes.

Their fine novels share some features. Both are family stories told by first-person narrators who are young (teenage) independent-minded women with wilful fathers. Both novels reimagine periods of Australia’s past: the first decade of the 20th century in Rush Oh! and the mid-19th century in Salt Creek. Both evoke a strong sense of place through coastal settings: the Coorong (Sth Aust.) in Salt Creek and Eden (NSW) in Rush Oh! Yet in tone, plot and theme they differ substantially.

The location named in the title of Salt Creek is remote and lonely, an area newly opened to pioneers willing to develop the harsh land.

For the Finch family, which has recently come down in the world, it’s a hard-scrabble existence. Financial difficulties are compounded by rash decisions and troubled relationships.

As a local Aboriginal boy from the dispossessed Ngarrindjeri people becomes drawn into their lives, values are sorely tested, secrets emerge, and young Hester Finch begins to question the assumptions held by her family about the very nature of civilisation.

One of the surprising qualities of Rush Oh! is that much of it is humorous in tone, despite the often painful and sometimes gory subject matter. It’s told by Mary Donaldson, eldest daughter of a family whose father dominates the small-scale whaling operations on which their town depends. Men in little boats work in deadly yet affectionate partnership with pods of orcas to bring large migrating whales within harpoon range. Magnificent animals are slaughtered, brave men perish, but there are also moments of whimsy and hilarity, adolescent romance and disappointment, bafflement and insight.

Mary’s portrayal of her family and community members is always lively, producing many memorably individualised characters, but it is her own equable temperament that holds the story together.

The other writer participating in this PWF session on ‘Reimagining’ is from England. Guinevere Glasfurd, like Lucy Treloar and Shirley Barrett, already has an aura of success to enhance her debut as a novelist. On the basis of her short fiction she has won awards from the Arts Council of England and the British Council. What’s more, although her novel The Words in My Hand has just been released in English, a German translation of it was published six months ago to great acclaim. In one notable respect, The Words in My Hand resembles Rush Oh! and Salt Creek: it is in large part the story of a teenage girl’s yearning for love, seen through her own eyes. Set in the 17th century and based on fact, it explores the relationship between a Dutch maid, Helena Jans, and the renowned French philosopher, René Descartes.

While all three novels are first-person narratives, the storytelling method in The Words in my Hand takes on an additional challenge: through the medium of English it tries to create the idiom of someone whose own language is actually Dutch, whose lover’s language is French, and whose rudimentary literacy is hard-earned.

In our festival conversation I’m hoping to hear what each writer thinks about the pros and cons of her chosen voice and point of view. There will be no shortage of other topics, too, and these are all fascinating novels, so if you’re in Perth on Sunday 21st February do come along to this session. It’s a free event.

By the way, I’ll also be appearing in one of the Human Library sessions devised for PWF by the UK’s Empathy Museum. The “books” in this library are individuals with stories to share: visitors will hear from and talk with three living books over an hour-long session. My session is on Sunday 21st at 2.30 in the Sunken Garden (UWA campus), one of a series on the theme of “age.” This is a free but ticketed event – bookings can be made here.

The post Debut novelists – but hardly novices appeared first on Reid on Writing.

January 25, 2016

Why should governments fund writers’ centres?

A recent article by Victoria Laurie in The Australian reported what some of us already knew: that government funding for literary activities in Western Australia has been slashed for 2016.

A recent article by Victoria Laurie in The Australian reported what some of us already knew: that government funding for literary activities in Western Australia has been slashed for 2016.

As the report notes, several cutbacks during the last year have substantially reduced financial support for authors, publishers, and associated organisations in this state. These include turning the WA Premier’s Book Awards from an annual into a biennial event – which, as WritingWA CEO Sharon Flindell remarks, ‘has essentially halved opportunities for authors and publishers to promote their work.’ Also stripped away has been some of the Australia Council funding for literature in Western Australia.

And now the unkindest cut of all has discontinued the grants previously provided by the state’s Department of Culture and the Arts for a number of vital operations, such as the magazine Westerly, the Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA), and – most astoundingly – the peak coordinating body WritingWA, which represents every link in the book industry supply chain through 80 member organisations.

Laurie’s article quotes statements of distress by a number of writers and others involved in the production and promotion of books. Although they all have reasonable things to say, I suspect that a casual observer would probably dismiss those concerns with a shrug, thinking it’s just a case of cottage-industry practitioners expecting the taxpayer to subsidise their individual pursuits indefinitely and having a whinge about the prospect of reduced privileges such as trips to literary festivals etc.

What doesn’t come through in Victoria Laurie’s article is the strong business case for supporting such activities because their demonstrable public impact is achieved so thriftily. Take WritingWA as the prime example: it has delivered an exceptionally good return on investment, stretching the value of every funding dollar by forming several very productive partnerships regionally and nationally. Its work has been almost as miraculous as the fabled feeding of the 5000 with a few loaves of bread and a couple of fish.

I’ve written elsewhere about the enterprising ways in which WritingWA manages to maximise the range of practical benefits it confers not only on individual writers but on communities across the state. I’ve also spoken about this in recent radio interviews, locally and nationally. Examples are worth repeating here. WritingWA maintains strong working relationships with the following:

Westlink TV, resulting in an outstanding publicity vehicle for writers – Meri Fatin’s monthly “Cover to Cover” program, showcasing WA writers and reaching out through community centres to many regional locations.

Literary festivals. I’ve seen at first hand (e.g. in Geraldton, Kununurra and the Avon Valley as well as in Perth) how valuable this kind of liaison can be, not only for writers but also for diverse communities.

The Literature Board of the Australia Council, e.g. in a jointly organised workshop on Market Development Skills for writers – again, developing good business practice.

The West Australian newspaper, for which WritingWA works with its literary editor Will Yeoman to ensure prominent coverage of books produced in this state.

Public libraries, e.g. assisting with payment for writers who give library talks and readings.

It’s unfortunate that this point about leveraged business efficiency and the $$ multiplier effect, extending community access to cultural resources, wasn’t made forcefully in the newspaper report. Anyone outside literary circles who glances at it will probably not have taken away a clear message about the admirably resourceful way in which WritingWA has extracted extra value for the community from every invested dollar.

The post Why should governments fund writers’ centres? appeared first on Reid on Writing.

January 11, 2016

Puss in Books

During the peak holiday season an injured cat dominated my life. On Xmas Day my grandson’s furry pet, having ventured onto a highway, was admitted with three pelvic fractures to a vet hospital and soon underwent surgery. For most of the next fortnight, until the ‘owner’ family returned from overseas, I spent many vigilant hours each day sitting beside this invalid, trying to administer medication, coax her to eat and drink, prevent her from licking or picking at the stitched wounds, etc.

Naturally my thoughts drifted idly through various depictions of cats in books.

Sometimes other cultural media disseminate what begins as literary material. Umpteen thousands of people who never read poetry have enjoyed T.S. Eliot’s versified portraits in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats through Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical settings.

As you probably recall, the whimsical gallery of whiskered characters includes Mr Mistoffelees the conjurer, who ‘produced seven kittens right out of a hat’; Macavity the elusive arch-criminal, ‘the bafflement of Scotland Yard’; and Gus the elderly theatre cat, who ‘suffers from palsy that makes his paw shake.’ I first met them on the page, long before Cats was devised for the stage.

Unsurprisingly, cats feature in the work of several famous writers for children – among them Terry Pratchett, Beatrix Potter, Roald Dahl and Lynley Dodd.

Some of these creatures have a repertoire of magical powers – as do Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire grinner in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, able to make itself invisible, and Dr Seuss’s Cat in the Hat, a trickster whose tale liberated early childhood language learning 60 years ago from the inanity of Dick-&-Jane primers while exemplifying the value of phonics in reading.

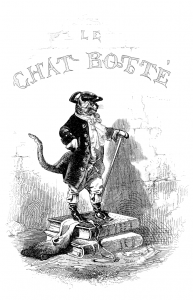

And let’s not forget that master of deceit who cunningly presides over one of the best-known fairy tales, Puss in Boots.

Puss in Boots is of French origin (appearing in Charles Perrault’s 17th-century compilation of traditional tales), and French writers seem to be especially impressed by cats. An example that comes to mind is La Chatte (1933) by French novelist Colette, which presents a love triangle: a woman, her husband and his Chartreux cat. The cat wins, of course.

Puss in Boots is of French origin (appearing in Charles Perrault’s 17th-century compilation of traditional tales), and French writers seem to be especially impressed by cats. An example that comes to mind is La Chatte (1933) by French novelist Colette, which presents a love triangle: a woman, her husband and his Chartreux cat. The cat wins, of course.

Then there’s the 19th-century poet Charles Baudelaire, so infatuated with cats that when visiting a household he would often devote his attention entirely to the resident cat and ignore its human companions. His famous book Les Fleurs du Mal includes three cat poems, one of which I’ve just been re-reading, trying my hand at a translation of its final two stanzas, wrestling with the challenge of retaining their pattern of tetrameter quatrains, rhymed abba:

Quand mes yeux, vers ce chat que j’aime

Tirés comme par un aimant,

Se retournent docilement

Et que je regarde en moi-même,

Je vois avec étonnement

Le feu de ses prunelles pâles,

Clairs fanaux, vivantes opales

Qui me contemplent fixement.

When drawn towards this cat I love

as if magnetically, my gaze

Turns inward in obedient ways

To look upon myself, then move

The line of my astonished sight

Back to those pale but glowing eyes,

Like living opals, which surprise

And fix me in their beacon light.

Baudelaire’s American counterpart, Edgar Allan Poe, was similarly preoccupied with depression and depravity, macabre stories, unorthodox sexuality, and feline companions. As a child I read his sinister story ‘The Black Cat’ and it scared me. A Perth writer, my friend Brenda Walker, has explored some of these themes in her unusual novel Poe’s Cat.

Being over-fond of cats may make some of us seem a bit crazy, but of all animals they’re perhaps best equipped to provide solace in one’s madness. In the mid-18th century, Christopher Smart’s sole companion during years of incarceration for insanity was his cat Jeoffry, to whom Smart devoted part of his idiosyncratic pseudo-Hebraic poem Jubilate Agno. Among other attributes, Jeoffry is admired for his ‘mixture of gravity and waggery’, and for the way he enjoys ‘wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.’ There is, Smart observes, ‘nothing sweeter than his peace when at rest’ and ‘nothing brisker than his life when in motion.’

I have a cat friend just like that. These days, in her maturity, she’s more often ‘at rest’ than ‘in motion.’

And she’s a suitable companion for a writer because of her bookish inclination.

The post Puss in Books appeared first on Reid on Writing.