Edward Willett's Blog, page 63

May 24, 2011

Unrealistic expectations, and why they're good for you

A few years ago (35 still counts as a few, right?) I was valedictorian for my high school class. This entailed making a speech. Since the theme of our class was "Climb Every Mountain" (why, yes, we had produced The Sound of Music that year; how did you guess?), my speech was based on an extended metaphor: high school as a place of mountain-climbing instruction.

A few years ago (35 still counts as a few, right?) I was valedictorian for my high school class. This entailed making a speech. Since the theme of our class was "Climb Every Mountain" (why, yes, we had produced The Sound of Music that year; how did you guess?), my speech was based on an extended metaphor: high school as a place of mountain-climbing instruction.

I'd love to tell you exactly what I said, but I think the paper I wrote the speech on crumbled to dust long ago. Still, I'm pretty sure I expressed optimism about the future and said something about "scaling peaks" and "reaching for the sky" and so forth and so on, yada-yada-yada.

Optimism about the future is par for the course for graduation and commencement speakers…even though experience teaches us that that optimism is often misplaced. Lots of students imagine they're going to change the world/be fabulously wealthy/be a rock star/etc., etc., etc. Very few of them actually do.

But you know what? That's okay. Because as Tali Sharot, a research fellow at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at University College London, recently wrote in an article in the New York Times, by and large, optimism is good for you.

Sharot, author of the book The Optimism Bias: A Tour of the Irrationally Positive Brain, points out that being optimistic (or, as he puts it "underestimating the obstacles life has in store"), lowers stress and anxiety, which in turn leads to better health and well-being.

Optimists, he notes, recover faster from illnesses and live longer. And, of course, if you believe there is a possibility you can achieve your dreams, you're more likely to work toward those dreams…which, in turn, makes it more likely you actually will achieve them. If you believed your efforts were doomed from the beginning (as, sad to say, they often are), you wouldn't even try…and trying, though it may not get you all the way to your goal, will almost certainly get you at least part of the way to your goal, and maybe that's good enough.

Optimism seems to be hard-wired into our brains. Surveys have shown that students expect more job offers, higher salaries, longer-lasting marriages, and better long-term health than statistically they have any right to expect…even when they are fully aware of the statistics for unemployment, divorce, cancer or heart disease.

Nor is optimism a function of how well off you are or what part of the world you live in. Studies show that 80 percent of the population, without regard to age, country of residence, ethnic background or gender, has an optimism bias.

That puzzled scientists before the advent of modern brain-imaging techniques. But we now have evidence, Sharot says, that when we learn what the future may hold, our neurons are very good at encoding unexpectedly good information—but fail to incorporate information that is unexpectedly bad.

So if we hear about someone born poor who became fabulously wealthy, we think, "That could happen to me!", whereas when we are told that the likelihood of someday being unemployed is one in 10 or the odds of suffering cancer are over one in three, we pay it no nevermind (as my southern kinfolk would put it).

Of course, there can be a down side to unrealistic optimism, as well. Underestimating risk leads to dangerous driving, failure to save for retirement, and a reluctance to undergo medical screenings.

Globally, misplaced optimism has even caused economic disaster. The financial crisis of 2008, Sharot suggests, came about because investors, homeowners, bankers and economic regulators all expected slightly better profits then were realistic. Combined, those unrealistic expectations led to a financial bubble that, when it collapsed, caused huge losses.

Sharot quotes Duke University economists Manju Puri and David T. Robinson, who like to say that optimism is like red wine: a glass a day is good for you, but a bottle a day can be hazardous.

And so, graduates, let me leave you with these inspiring words: climb every mountain, but make sure your ropes are secure, check the weather forecast before you begin, and don't be afraid to go back to the bottom and start all over again.

Or as Sharot puts it, in words that go straight to my young adult-fantasy-writing heart, "aspire to write the next 'Harry Potter' series, but have a safety net in place, too."

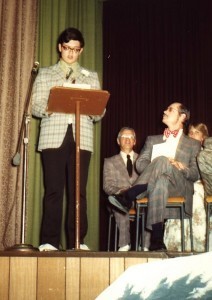

(The photo: Me, speechifying as valedictorian of the Class of 1976, Western Christian College.)

May 21, 2011

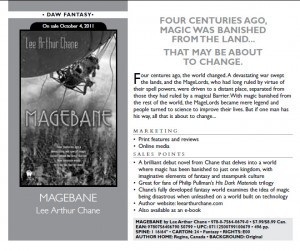

Magebane marketing

New American Library (under whose umbrella my publisher DAW Books falls) has distributed its catalogue to booksellers for its October releases, which include Magebane. This image shows the relevant page.

New American Library (under whose umbrella my publisher DAW Books falls) has distributed its catalogue to booksellers for its October releases, which include Magebane. This image shows the relevant page.

The text reads:

Four centuries ago, Magic was banished from the land…

that May be about to change.Four centures ago, the world changed. A devastating war swept the lands, and the MageLords, who had long ruled by virtue of their spell powers, were driven to a distant place, separated from those they had ruled by a magical Barrier. With magic banished from the rest of the world, the MageLords became mere legend and people turned to science to improve their lives. But if one man has his way, all that is about to change…

Under sales points, we get:

• A brilliant debut novel from Chane that delves into a world where magic has been banished to just one kingdom, with imaginative elements of fantasy and steampunk culture

• Great for fans of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy

• Chane's fully developed fantasy world examines the idea of magic being disastrous when unleashed on a world built on technology

• Author website: leearthurchane.com

• Also available as an e-book

Two comments:

"Brilliant debut novel." Gee, no pressure.

And, I'd better get to work on leearthurchane.com, 'cause there's nothing there yet.

(Oh, yeah, and as noted previously, that's now "eight centuries," not "four.")

May 17, 2011

The Shatner effect

We'd like to think that we're extremely rational beings who, when listening to someone trying to convince us of something, cannot be influenced by such superficial things as the person's appearance or the way he or she talks.

We'd like to think that we're extremely rational beings who, when listening to someone trying to convince us of something, cannot be influenced by such superficial things as the person's appearance or the way he or she talks.

We'd like to think that, but we'd be wrong, as any number of studies have shown over the years.

Case in point: new research conducted at the University of Michigan that found that the speed at which someone talks, the number of pauses they use, and, to a certain extent, even the pitch of his or her voice, influence how willing we are to do what they say.

The study, presented May 14 at the annual meeting of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, specifically measured how these various speech characteristics influenced people's decisions to participate in telephone surveys, but it's quite likely the findings hold true in many other situations as well, from conversations with our bosses to conversations with our spouses.

Jose Benki, a research investigator at the university's Institute for Social Research, and colleagues began their study by analyzing 1,380 introductory calls made by 100 male and female telephone interviewers at the Institute. They correlated the interviewers' speech rates, fluency and pitch with their success in convincing people to participate in a survey.

When it came to speech rates, they found that interviewers who talked moderately fast (about 3.5 words per second) were much more successful than interviewers who talked very fast or very slowly.

That makes sense: people who talk quickly can be seen as trying to "pull a fast one," whereas people who talk too slowly can be seen as either not too bright…or just pedantic.

But the next finding was less intuitive. Going in, the researchers assumed that interviewers who sounded lively and animated, who used a lot of variation in the pitch of their voices, would be more successful. Instead, they found that variation in pitch only had a marginal impact.

"It could be that variation in pitch could be helpful for some interviewers but for others, too much pitch variation sounds artificial, like people are trying too hard," Benki is quoted as saying in a university press release. "So it backfires and puts people off."

As for pitch in general, the researchers did not find any clear-cut evidence that, when it came to female voices, altos did better than sopranos, or vice versa. They did find that higher-voice males had worse success than their deep-throated colleagues, which I, being of the bass rather than tenor persuasion, am pleased to hear (as is James Earl Jones).

The most interesting finding of all was that those who were perfectly fluent, without any pauses in their speech, were actually less successful at persuading people to take the survey than were those who paused four or five times a minute. The pauses might be silent, or "filled" (i.e., "um").

The lowest success rates of all belonged to people who did not have those pauses in their spiels. "We think that's because they sound too scripted," said Benki. "People who pause too much are seen as disfluent. But it was interesting that even the most disfluent interviewers had higher success rates than those who were perfectly fluent."

Benki and her colleagues plan to continue analyzing the speech of the most and least successful interviewers to see how the content of the conversations and the quality of their speech influenced their success (or lack of it).

So let's recap. People who speak neither too fast nor too slow, men with lower voices and…finally…those who…pause…as they speak…are more likely to be…persuasive…than those…who have none of these…characteristics.

You know what this means, don't you?

Science has finally discovered why James Tiberius Kirk was the greatest Starfleet captain of them all!

And with William Shatner having just been honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Governor General's Performing Arts Award Foundation, about time, too.

(The photo: My favorite Star Trek character of all time, Ensign Alice, at the 2002 World Science Fiction Convention in San Jose.)

May 10, 2011

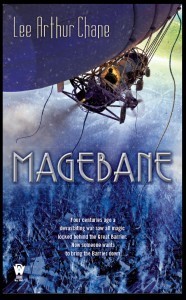

Cover art for Magebane!

Just got this today: the cover art for Magebane, the first fantasy novel by my alter ego Lee Arthur Chane. It's by Paul Young (and you can see more of his artwork here). The cover blurb will change slightly, because in the course of revisions that reference to "four centuries" became "eight centuries," but otherwise, this is what you'll see on the shelves come October 4.

Just got this today: the cover art for Magebane, the first fantasy novel by my alter ego Lee Arthur Chane. It's by Paul Young (and you can see more of his artwork here). The cover blurb will change slightly, because in the course of revisions that reference to "four centuries" became "eight centuries," but otherwise, this is what you'll see on the shelves come October 4.

Do I like it? Well, yeah! The airship isn't a perfect rendition of the airship in my head, but that's hardly surprising. It's got the right feel. And it's definitely eye-catching!

I'm already discussing ideas for the second Lee Arthur Chane book with Sheila Gilbert, my editor at DAW Books. She seems to like the notion I'm tossing around. Now all I have to do is flesh it out into a formal proposal…for a multi-book series, I might add. So that's high on my to-do list over the next few weeks. Very high. Whee!

May 9, 2011

Remembering our dreams

We're all familiar with it. You're having an absolute terrific dream, enjoying every minute of it. Then the alarm goes off. For an instant the sound become part of your dream…then you're awake. You try to hold on to the dream, because it was really fabulous and funny and you want to tell your spouse about it…

We're all familiar with it. You're having an absolute terrific dream, enjoying every minute of it. Then the alarm goes off. For an instant the sound become part of your dream…then you're awake. You try to hold on to the dream, because it was really fabulous and funny and you want to tell your spouse about it…

…but it's already fading. By the time you get to the shower, all that remains is a faint sense of how the dream made you feel…and regret that you can't remember it.

Now Italian researchers think they've figured out why we remember some dreams, but not others. But first, a little refresher on dreams and what we know about them.

Dreams, of course, have fascinated people for millennia. Most of us don't believe they portend the future any more, but you'll still find plenty of people who think you can interpret your dreams for fun and profit.

The function of dreams still isn't universally agreed upon. Some scientists think they must have a survival function (why else would we have evolved them?), while others think they're an unimportant byproduct of the way our brains work.

We do have some solid data. Research has told us three-quarters of our dreams are in colour and two-thirds include sound, but only about one percent include touch, taste or smell.

Men (perhaps surprisingly) most often dream about men; women dream about men and women equally.

Women's dreams are typically more emotional and have fewer people in them, though they tend to include more social interaction and more clothes: men tend to dream about money, weapons and nudity.

Dreaming takes place during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, which lasts from 10 minutes to half an hour, four to six times a night. During REM sleep your previously comatose brain suddenly erupts with activity. Your eyes move rapidly under your closed eyelids, and your heart rate, breathing rate and blood pressure go up. (Fortunately, your body remains effectively paralyzed.)

A study a few years ago showed that during REM sleep the frontal lobes, which integrate information, help us interpret the outside world, and contain working memory, are shut down—while much of the rest of the brain is highly active. That could explain why our dreams are so vivid and gripping, even though they don't make a lick of sense. With our frontal lobes out of the picture, dreams are being driven by emotion, not logic. And without working memory, the dreaming brain forgets what just happened in the dream—which is why you can step out of your kitchen onto the top of the Empire State Building, while your companions morph from friends to large shaggy dogs.

We dream about 90 minutes every night, but we usually only remember a dream every four or five days.

Now Luigi De Gennaro at the University of Rome and his team have discovered what's going on in our brains when we remember our dreams.

The researchers monitored 65 students with an electroencephalogram (EEG) while they slept. Thirty had been identified as people who habitually wake up while in REM sleep, and 35 were people who usually wake up in Stage 2 non-REM sleep. About two-thirds of both groups recalled dreams during the study.

The researchers found that those who woke during REM sleep and successfully recalled their dreams were more likely to demonstrate a pattern of theta waves in their frontal and prefrontal cortexes, where advanced thinking occurs. The patterns and the part of the brain involved were the same as those important for awake subjects recalling memories.

Those who woke up in non-REM sleep had patterns of alpha wave activity in the right temporal lobe, the area of the brain involved in recognizing emotional events. Again, this was similar to activity known to be key for memory recall when awake.

The researchers interpret this to mean that even when we're asleep, our brain is alert for things that are important enough to remember, often things that are emotionally charged.

Proof enough, I say, that dreams have survival value. Because the next time I open the front door of my house to discover a giant squid devouring my television while a poodle in a smoking jacket sits in my armchair and laughs, at least I won't be taken completely by surprise.

If that doesn't have survival value, I don't know what does.

May 2, 2011

The foundation of psychohistory?

In his famous Foundation series (published six decades ago now), science fiction writer Isaac Asimov postulated a fictional branch of mathematics, discovered by scientist Hari Seldon, known as "psychohistory," which could predict the future. Psychohistory was based on the principle that the behavior of a mass of people is predictable if the quantity of the mass is very large.

In his famous Foundation series (published six decades ago now), science fiction writer Isaac Asimov postulated a fictional branch of mathematics, discovered by scientist Hari Seldon, known as "psychohistory," which could predict the future. Psychohistory was based on the principle that the behavior of a mass of people is predictable if the quantity of the mass is very large.

Psychohistory came to mind when I read a recent article by Robert Lee Holtz in the Wall Street Journal outlining the research being conducted using the vast amounts of data collected by mobile phones.

According to Holtz, scientists are finding that, using the data collected through these ubiquitous communications devices (now in use by, incredibly, almost three-quarters of the world's population), they can make amazingly accurate predictions about human behavior.

They can pinpoint "influencers"( people who are most likely to make others change their minds), predict where people will be in the future, detect subtle symptoms of mental illness, forecast movements in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and even chart the spread of political ideas.

What makes this all possible, as Holtz points out, is that the locations of mobile phones are routinely tracked by phone companies (necessarily, since they must be connected to the nearest cell tower). As well, for billing purposes, the timing and duration of calls have to be logged, along with the user's billing address.

Phones log calling data, messaging activity and online activities. Many are equipped with sensors to record movements, a compass, a gyroscope and an accelerometer. They can even take photos and videos.

A modern cellphone is, in other words, an enormously powerful data collection device. Holtz quotes Dr. Alex Pentland at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as saying that phones allow researchers to get a "god's-eye view of human behavior."

Dr. Pentland has spent most of the last two years tracking 60 families living in campus quarters. By combining data from their smartphones with additional reports the participants file, he has recorded their movements, relationships, moods, health, calling habits and spending.

This follows up on a previous study during the final three months of the 2008 presidential election that tracked face-to-face encounters among 78 students. That study revealed that a third of the students changed their political opinions, and those changes were related to their face-to-face contact with project participants with different views, rather than encounters with their friends or exposure to traditional campaign advertising.

The new work is providing even more information about what Pentland calls "the molecules of behavior." He says that "just by watching where you spend time, I can say a lot about the music you like, the car you drive, your financial risk, your risk for diabetes. If you add financial data, you get an even greater insight."

Other researchers are using amounts of cellphone data so vast that they see humans as "little particles that move in space and occasionally communicate with each other," as physicist Albert-Laszlo Barabasi of Northeastern University in Boston puts it. He led an experiment which studied the travel routines of 100,000 European mobile-phone users, and found that people's movements follow a mathematical pattern: with enough information about past movements, the scientists could forecast an individual's future whereabouts with 93.6 percent accuracy.

The amount of data available to be crunched is incredible. Nathan Eagle, a research fellow at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, works with 200 mobile-phone companies in 80 countries. One of his research data sets encompasses half a billion people in Latin America, Africa and Europe. (Among his findings: slums can be a catalyst for a city's economic vitality, serving as "economic springboards" as entrepreneurs seek a way out of them.)

Going forward, researchers hope to use information gathered from mobile phones to improve public health, urban planning and marketing…and to continue to explore the basic rules of how humans interact with each other.

Which, Holtz points out, brings us back to the issue of privacy.

"We have always thought of individuals as being unpredictable," he quotes Johan Bollen, an expert in complex networks at Indiana University, as saying. "These regularities [in behavior] allow systems to learn much more about us as individuals than we would care for."

Hari Seldon was unavailable for comment.

(The photo: Flooding at Wascana Country Club, Regina, Saskatchewan, Easter Sunday, 2011.)

April 25, 2011

Embarrassment

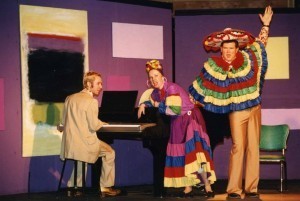

Some people are easily embarrassed. Some, not so much. I, for example, have no problem at all singing in public. (Here's proof!). That's not true for everyone.

Some people are easily embarrassed. Some, not so much. I, for example, have no problem at all singing in public. (Here's proof!). That's not true for everyone.

Which is why, I guess, that researchers studying the neurological basis of embarrassment recently chose to trigger embarrassment by making people listen to recordings of themselves singing. Oh, the horror!

Apparently it's a pretty reliable way to make people feel embarrassed, although I'm not sure how they screen for people like me who actually enjoy listening to recordings of ourselves.

Anyway, the method of engendering embarrassment wasn't really the point of the study (although it's certainly why I noticed it). The goal was to identify the neurological basis of embarrassment, and the study has given a strong indication that the seat of embarrassment in the human brain is, in fact, a thumb-sized piece of tissue in the right hemisphere of the front part of the brain.

The study was conducted by a team of scientists at the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of California, Berkeley.

The study was based on the long-documented fact that people suffering from a group of related neurodegenerative conditions called frontotemporal dementia do things without embarrassment that would be embarrassing to most healthy people.

The temporal and frontal lobes of the brain play a significant role in decision-making, behavior and understanding and expression of language and emotion–including embarrassment.

So for this study, the researchers, led by Virginia Sturm, a postdoctoral fellow at UCSF, took 79 people, most of whom suffer from neurodegenerative diseases, and asked them to sing "My Girl," the 1964 Motown hit by The Temptations, with a karaoke accompaniment.

According to Sturm (and rather worrying for me), "In healthy people, watching themselves sing elicits a considerable embarrassment reaction." Specifically, their heart rate and blood pressure both increase, and their breathing changes.

While they sang, probes measured their vital signs and cameras videotaped their facial expressions. Their songs were recorded, and then they were played back to the singers at normal speed–but without the accompanying music. Sturm and the other researchers assessed how embarrassing they found this, based on facial expressions and things such as sweating and heart rate.

Then, they put all the people through MRIs to make extremely accurate maps of their brains, which were then used to measure the volume of different regions of the brain, to see if they could find a link between the sizes of various regions and the level of embarrassment.

The result: people whose pregenual anterior cingulate cortex had deteriorated significantly were less likely to be embarrassed, and the more it had deteriorated, the less likely they were to be embarrassed by their own singing.

By way of a control, the study participants were given a "startle" test, which measures emotional reactivity: they sat quietly in a room until they were surprised by a gunshot sound.

The subjects did jump and were frightened by the sound, Sturm noted, "so it's not like they don't have any emotional reactions at all." But, she said, "Patients with loss in this brain region seem to lose these more complicated social emotions"…such as embarrassment.

No, this doesn't mean that just because you don't get embarrassed watching yourself sing you have a neurodegenerative disorder. It may just mean you're a ham. ("Le jambon, c'est moi!")

Whereas changes in thinking and memory are usually easily identified by family members and doctors, changes in emotion and social behavior, being more subtle, can be missed. The researchers hope that a better understanding of the neurological basis of these changes may help loved ones and caregivers cope better with the more severe behavioral changes that can result from neurodegenerative conditions.

As for the rest of us…well, it probably doesn't really help the easily embarrassed to know that the physiological source of embarrassment is the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex. It's simplistic to say that if you have a big one you're more likely to be embarrassed than if you have a small one. (There's a joke there somewhere that I'm trying really hard to avoid.)

Embarrassment is a very complicated emotion and not one that's fully understood by any means.

Still, this is another example of how, bit by bit, we're mapping the regions of the brain responsible for the emotions that we experience as free-floating. We sense ourselves as being somehow separate from the wrinkled gray mass inside our skulls, but really, we're entirely contained within it.

It's a bit humbling, but honestly, it's nothing to be embarrassed about.

(The photo: Cocktails for Two Hundred at Souris Valley Theatre. That's me on the right, with Marianne Woods leaning on the piano and.)

April 18, 2011

Inattention blindness

There's a famous video (well, famous in some circles, anyway) of six people passing a basketball around. Midway through, a person wearing a gorilla suit walks through the scene.

There's a famous video (well, famous in some circles, anyway) of six people passing a basketball around. Midway through, a person wearing a gorilla suit walks through the scene.

Research has shown that when viewers who have been told to count the number of passes don't know the person in the gorilla suit is going to appear, more than 40 percent fail to see him, even though he stops halfway across the room to briefly thump his chest.

This failure to see something unusual that's right in front of our eyes is called "inattention blindness," and new research has shed some light on who is most susceptible to it, and why.

The key, it appears, is the capacity of a person's working memory, the memory we use to deal with whatever we're doing at any given moment. If you're solving a math problem, or working on a grocery list, you're using working memory.

The question has been whether people with a high working memory capacity are less likely to see a distraction because they focus more intently on the task at hand, or more likely to see it because they are better able to shift their attention as needed.

New research indicates it's the latter: those with greater working memory capacity are more likely to see the gorilla than those with less.

The research was conducted by University of Utah psychologist Janelle Seegmiller (the video was the work of psychologists Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons, who wrote a book called, naturally, The Invisible Gorilla), along with fellow psychology faculty members Jason Watson and David Strayer. Strayer has led several studies on cell phone use and distracted driving.

To begin, 306 psychology students were tested with the gorilla video. About a third were promptly excluded because they already had some knowledge of it. That left 197, ages 18 to 35, whose test results were analyzed.

First, the psychologists measured the participants' working memory capacity using an "operation span test" in which they were given a set of math problems, each of which was followed by a letter. (For example: "Is 8 divided by 4, then plus 3, equal to 4? A.")

There were 75 of these equation-letter combinations in all, divided into sets of three to seven. Participants were asked to recall all the letters of each set. For instance, if a set of five equations ended with PGDAE, they'd get a full five points if they remembered the letters in that order. (Although there was a catch: to ensure they weren't just memorizing the letter order, they also had to solve at least 80 percent of the equations correctly.)

In the next step the participants watched the gorilla video, which features two three-member teams, one wearing red shirts, one wearing black shirts, passing basketballs back and forth. Participants were asked to count bounce passes and aerial passes by the black team. At the end, they were asked how many passes of each kind they counted, and whether they noted anything unusual. To ensure they were actually counting passes, and so were focused on the task in hand, only participants who were 80 percent accurate in their pass count were included in the final analysis.

The overall results were very similar to those noted by Simons and Chabris: 58 percent of participants who were reasonably accurate in counting passes noticed the gorilla, but 42 percent did not. When that was correlated with the working memory capacity test, the researchers found that the gorilla was noticed by 67 percent of those with high working memory capacity, but only 36 percent of those with low working memory capacity.

To put it in other words, those with greater working memory capacity have more "attentional control": they are better able to focus attention when and where needed, and on more than one thing at a time.

Outside the lab, attentional control is important any time we're trying to deal with more than one task at once. The most obvious real-world example is driving. Those with a greater working memory capacity are less likely to run a just-turned red light because they're distracted by conversation, for instance.

It's an interesting finding, but don't think just because you have a higher working memory capacity, you can safely drive and talk on your cellphone at the same time. Previous research by this same team has shown that only a very few people (2.5 percent) can do so without impairment.

This probably still isn't the whole story. At least, the Utah researchers don't think it is: they plan to continue their research to look at other possible explanations for why some people suffer more from inattention blindness than others, including brain processing speed and differences in personality types.

Personally, I've always thought I'm very good at multitasking. I was doing four other things while writing this column, and I'll bet you no close you matter how look can't tell, can you?

(The photo: Gorillas in wash tubs at the Calgary Zoo.)

April 10, 2011

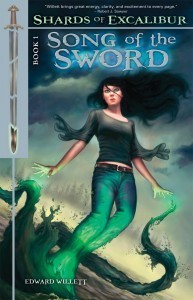

Song of the Sword "a great new spin on a familiar story"

A brief new review of Song of the Sword at the blog think.thank.thought (a trail of reading) says:

A brief new review of Song of the Sword at the blog think.thank.thought (a trail of reading) says:

Song of the Sword is carried by an exciting plot that gives a great new spin to a favourite story. It can also take credit for a great cast of characters…set up to play out what might become the battle of the ages. I can see that exciting adventures await as they all struggle to decide what's worth fighting for: power, friends, or family.

I'm looking forward to the rest of this series!

Read the whole thing.

April 9, 2011

Marseguro reviewed by a talking moose…

Actually, thetalkingmoose is the LiveJournal handle of the proprietor of a blog called The Moose Pit, and this morning I ran across his/her/its review of Marseguro. An excerpt:

Marseguro…stood out for me because it presents a compelling presentation as to why the human race will never truly become unified behind one government. Even a powerful governing organization such as The Body Purified, which possesses the means and the ruthless willpower to mercilessly slaughter both those who they feel must be destroyed to appease God and those who oppose it, must constantly use and replenish those resources to enforce its will. That doesn't even take into account internal power grabs and infighting amongst those who are ostensibly working for a common cause can create fissures that threaten to turn "true believers" against each other.

After finishing the novel, I found that there is — unsurprisingly, given the ending — a sequel, Terra Inseguro. It's very likely I will track it down as the ending of the book left me genuinely wondering what will happen to The Body Purified following its attempt destroy the Selkies and the other inhabitants of Marseguro.