Edward Willett's Blog, page 60

October 11, 2011

Driving green for fun and prizes

As regular readers of this blog will by now realize, Ford keeps letting me drive their vehicles in exchange for writing about them. Which is a sweet deal, you have to admit. Even if the vehicles aren't always to my taste (hello, giant red F150 pickup!), I enjoy driving them.

As regular readers of this blog will by now realize, Ford keeps letting me drive their vehicles in exchange for writing about them. Which is a sweet deal, you have to admit. Even if the vehicles aren't always to my taste (hello, giant red F150 pickup!), I enjoy driving them.

Recently, though, the driving-Fords gig took a slightly different twist: I was invited to take part in a Green Driving Challenge. I and four others from Regina spent a couple of days each with a Lincoln MKZ Hybrid. The goal was to get the best gas mileage (er, kilometrage?) you could manage. The drive with the best results would win a fabulous prize.

Not having driven a hybrid before, I was a bit unprepared for their unusual (compared to ordinary cars) behavior.

To begin with, there's the fact that when you turn the ignition key, the engine doesn't start. The dash lights up (does it ever), but nothing else seems to happen: if you don't remember you're in a hybrid, your first thought is that you have the car in gear instead of in Park. But in fact, the car has started: it's just that it begins running on its batteries, and doesn't get that nasty old gasoline engine involved until you pull away from the curb.

Similarly, the engine shuts down whenever you come to a stop at an intersection, also a bit disconcerting, especially if, like me, you once owned a car that used to do the same thing back in the days when that was definitely a bug and not a feature, since it had no electric motor to get you moving again.

At first I drove the car rather normally. This produced alarming results on the instant gas-usage meter on the right side of the display, right next to the cute little cartoon of growing leaves (see, the more "green" you're driving, the more leaves appear: as I said, cute, but just a little, um, cartoonish; I could do without it, myself, despite being fully in touch with my inner child). I soon realized that you could use that gas-usage meter to keep your numbers low, but I think I realized it too late: although I managed a 6.7 l/100k final result, the winner of the challenge outdid me by about a litre/100k. In the end, I tied for second.

At first I drove the car rather normally. This produced alarming results on the instant gas-usage meter on the right side of the display, right next to the cute little cartoon of growing leaves (see, the more "green" you're driving, the more leaves appear: as I said, cute, but just a little, um, cartoonish; I could do without it, myself, despite being fully in touch with my inner child). I soon realized that you could use that gas-usage meter to keep your numbers low, but I think I realized it too late: although I managed a 6.7 l/100k final result, the winner of the challenge outdid me by about a litre/100k. In the end, I tied for second.

The trick to being uber-efficient? Not getting in a hurry, and letting the electrics do as much of the work as possible getting the car up to speed. Indeed, the only way I got down to 6.7 l/100k was to take a Zen approach to driving: step lightly on the accelerator, and then meditate while slowly easing up to the Nirvana of the speed limit. It's a relaxing way to drive on non-busy streets, but not very practical on a busy city street with people breathing down your tailpipe.

Still, there's no question it's a low-mileage vehicle, and beyond that, a very pleasant car to drive and to ride in. And however I may feel about the cartoon leaves, they do make you think about how you're driving…which can't help but make you a little bit greener.

After all, even if you're not formally involved in a green driving challenge, driving green is its own reward.

(Oh, sorry about the copied-from-the-Web images: I was so busy driving green I forgot to take any photos of the car while I had it.)

October 10, 2011

Alcohol on the brain

Human beings have been using and abusing alcohol for a very long time: roughly 10,000 years, give or take a long weekend.

Human beings have been using and abusing alcohol for a very long time: roughly 10,000 years, give or take a long weekend.

The effects of drinking too much of the stuff have been known for every one of those 10,000 years (although individuals somehow seem to forget them within a remarkably short time frame).

For decades, scientists have been trying to understand the mechanism behind the reduced muscle coordination and sedative effects of alcohol. The assumption has been that alcohol acts on the brain's neurons, but nobody could figure out exactly how.

A new study indicates that may be because they've been looking in the wrong place. Not only that, the study hints that it might be possible to create drugs that could be used to treat chronic alcohol dependence—or even to counter the short-term effects of drinking too much.

The study, out of Australia (a where people have been known to enjoy an occasional drink while throwing another shrimp on the barbie), indicates that these effects may not arise in the brain at all: instead, improbably, they may be caused by the way alcohol acts on the immune system.

The study focuses, as so many studies do, on mice.

Researchers at the University of Adelaide genetically engineered mice that are able to "hold their liquor" by deactivating something called the "Toll-like receptor 4," or TLR-4.

TLR-4 is a member of a family of receptors that induce inflammation, one of the body's main lines of defense against infection. TLR-4 was first identified in fruit flies, and is known to be present on immune-defence white blood cells in the bloodstream. It is also present on glial cells in the brain.

"Glial" comes from the Greek word for "glue," and for a long time glial cells were seen as little more than the glue that held the more important neurons together. But in fact, glial cells make up around 90 percent of the cells in the brain and play many important roles in brain function—including protecting the brain against infection.

It appears that alcohol activates the TLR-4 receptor, causing the glial cells in a part of the brain called the hippocampus to send out an inflammation signal: essentially, alcohol acts on the brain just like an infection would, and sedation and unsteadiness are the results.

The evidence? The mice genetically engineered so that TLR-4 was inactive were resistant to the behavioral effects of alcohol. Not only did they refrain from getting into bar fights with mice twice their size, they were able to stay perched on a rotating log longer and were sedated for a much shorter time than normal drunken mice. (You know, I don't believe I've ever before typed the phrase "normal drunken mice.")

Next, the researchers treated normal mice with a drug called (+)-naloxone, which blocks TLR-4. Sure enough, the drug also reduced the effects of alcohol, halving the duration of sedation and shortening the recovery time for loss of balance.

So, does that mean you'll someday be able to take a pill that blocks TLR-4 and then head out for an overindulgent evening without fear of consequences?

Um, no. The study showed that it might be possible to reduce the severity and duration of alcohol's effects: not eliminate them. Also, there are some effects of alcohol people actually want, and blocking TLR4 might actually block the pleasurable effects, too, so it would be unlikely to be popular with drinkers.

But this drug, or others to be developed that could be taken by mouth (the particular drug used in the study has to be injected, and in any event no one knows yet if it is safe for use by people, as opposed to mice) could play a valuable role in the emergency treatment of people suffering from an alcohol overdose.

Further, it seems likely that individual differences in TLR4 could account for individual differences in the effects of alcohol…which could give a means of determining how susceptible a particular individual is to its effects: perhaps someday your doctor will be able to tell you exactly how much alcohol you can enjoy without unpleasantness ensuing, or if you should avoid it altogether.

All I know is that if this research someday leads to a reduction in drunken karaoke, it will have made the world a better place for us all.

The photo: Wine glasses lined up ready for tasting at the 2010 International Festival of Wine and Food at the Banff Springs Hotel.

October 4, 2011

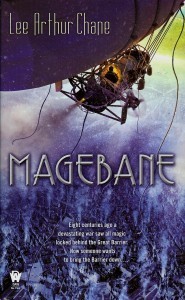

Magebane hits bookstores today!

Is it October 4 already? It is, and that means that Magebane is officially available, published (of course) by DAW Books. You can buy it in all the usual places: Amazon.com, Amazon.ca, Chapters, Barnes & Noble, to name just a few. And it's available in both paperback and popular ebook formats.

Is it October 4 already? It is, and that means that Magebane is officially available, published (of course) by DAW Books. You can buy it in all the usual places: Amazon.com, Amazon.ca, Chapters, Barnes & Noble, to name just a few. And it's available in both paperback and popular ebook formats.

Here's the blurb from the back, just to remind you what it's all about:

The kingdom of Evrenfels is the last bastion of magic in the world, cut off from the outside by the Great Barrier through which magic cannot penetrate.

For centuries, the Magelords have ruled their kingdom with an iron hand while beyond the Barrier, magic and the Magelords have faded into an almost forgotten myth, replaced by low-level technology. Now all of that is about to change, for one man, Lord Falk, the Minister of Safety—the most powerful of the Magelords—has plans to assassinate the king and his heir, to break down the Barrier, and to conquer the lands beyond.

All it will take is the lives of two innocents: Prince Karl and Falk's own ward, a girl named Brenna, a small sacrifice to Lord Falk's way of thinking. One is the heir and the other is the legendary Magebane, anathema to all magic.

But there is one thing Lord Falk hasn't foreseen, one thing that could unbalance all of his plans—the unexpected arrival of a young man whose airship suddenly comes sailing over the top of the Great Barrier…

So, for what are you waiting? Go forth and purchase! A dozen copies for yourself, and a couple for each of your friends (oh, be generous, give them to your enemies, too) and family sounds just about right to me.

Oh, and if you're local bookstore, through some horrendous oversight, does not have any copies, be sure to ask for it by name, OK?

I thank you for your support, and so does Lee Arthur Chane.

P.S. An interesting note about the cover. This is a scan from the actual book, and you'll notice the text at the bottom begins "Eight centuries ago…" Most of the cover art you'll see online says "Four centuries ago…" As do many of the online descriptions of the book. That's because I expanded the timeline in the final rewrite, after a lot of that stuff had already gone out. Fortunately, we were able to change the actual book cover!

September 30, 2011

The 2011 Ig Nobel Prizes

Ah, it's my favorite time of the year, a time when this column practically writes itself. It's Ig Nobel Prize time.

The Ig Nobel Prizes are presented by the science comedy magazine Annals of Improbable Research, to honour achievements that "first make people laugh, and then make them think."

At the ceremony, genuine (and "genuinely bemused") Nobel Laureates present the prizes. There are also other delights, such as mini-operas (this year's: "Chemist in a Coffee Shop") and, most notably, the 24/7 lectures, in which noted scientists explain their subject twice, offering a complete technical description in 24 seconds, followed by a concise summary anyone can understand in seven words (this year's topics: Stress Responses, Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes, Chemistry and Vagina pH). The ceremony can be watched online.

And now, without further ado, this year's winners:

The physiology prize went to a quartet of scientists from various countries for their riveting study, "No Evidence of Contagious Yawning in the Red-Footed Tortoise," which I find intriguing mainly because it seems to indicate there is non-contagious yawning in red-footed tortoises (tortii?).(Of course, if it took me that long to get wherever I was going, I'd be yawning before I got there, too.)

The coveted chemistry prize (this year's ceremony theme was chemistry) was won by researchers from Japan who figured out the ideal density of airborne wasabi needed to wake sleepers up in the case of an emergency, and then used that knowledge to invent their patented wasabi alarm. Buy now and get a free side-order of sushi! Supplies are limited, and operators are standing by!

The medicine prize went to researchers from the Netherlands, Belgium, the U.S. and Australia, for demonstrating in two separate studies that people make better decisions about some things, but worse decisions about other things, when they have a strong need to urinate.

Which reminds me, I'll be right back.

Much relieved, let us carry on. The psychology prize was won by Karl Halvor Teigen of the University of Oslo, for his study "Is a Sigh 'Just a Sigh'? Sighs as Emotional Signals and Responses to a Difficult Task."

Sigh.

Then there was the literature prize (near and dear to my heart), which went to John Perry of Stanford University for his Theory of Structured Procrastination, which states that to be a high achiever, you should work on something important, using it as a way to avoid doing something that's even more important. This is exactly my method of procrastination, assuming you consider playing word games on Facebook important.

The biology prize went to what may be the finest piece of Australian research ever: Darry Gwynne and David Rentz's discovery that a certain kind of beetle mistakes stubby beer bottles for female beetles, making them, if you'll pardon the expression, bottle-boinking beetles. And they don't even consume the contents first.

The prize for physics was won by researchers from France and the Netherlands for determining why discus throwers become dizzy and hammer throwers don't. Alas, no demonstration was forthcoming at the ceremony.

The mathematics prize went to a distinguished group who have collectively taught the world to be careful when making mathematical assumptions and calculations, namely Dorothy Martin of the U.S. (who predicted the world would end in 1954), Pat Robertson of the U.S. (who predicted the world would end in 1982), Elizabeth Clare Prophet of the U.S. (who predicted the world would end in 1990), Lee Jang Rim of Korea (who predicted the world would end in 1992), Credonia Mwerinde of Uganda (who predicted the world would end in 1999), and Harold Camping of the USA (who predicted the world would end on September 6, 1994, and when that didn't happen, predicted the world will end on October 21, 2011).

The peace prize was awarded to the mayor of Vilnius, Lithuania, one Arturas Zuokas, who demonstrated on video that the problem of illegally parked luxury cars can be solved quite easily by running over them with a tank. Mr. Zuokas was even present to receive his award in person.

And finally, a Canadian winner! John Sanders of the University of Toronto won the public safety prize for a series of safety experiments he conducted (back in the mid-1960s; it can take time for the brilliance of research to be properly noted) in which a person drove an automobile on a major highway while a visor repeatedly flapped down over his face, blinding him.

And there you have it. Research to make you laugh, make you think…and make you hide your beer bottles. I look forward to next year's Ig Nobel prizes.

Assuming the world doesn't end on October 21, of course.

My Mayor's Mega-Minute Reading Challenge speech

As writer-in-residence at the Regina Public Library, I was asked to give a brief speech at today's launch of Regina's annual Mayor's Mega-Minute Reading Challenge at Jack MacKenzie School. And rather than ad-lib, as is my wont, I actually wrote something down (not that I read it word for word). Here it is:

***

Hi, my name is Ed, and I'm a writer.

I've written around 50 books of one sort or other, from science fiction and fantasy novels to science books, computer books and history books, for children, young adults and adults.

But I didn't start out as a writer. I started out as a reader.

My parents loved to read, and I had two older brothers who also read a lot, so our house was always full of books. I remember practicing my reading with my mother by reading out loud to her. Since it was the King James Version of the Bible, I didn't always have a clue what I was reading, but at least I was figuring out how to sound out words.

What really captured my interest, though, was science fiction and fantasy. Again, I blame my brothers. That was what they read, and of course I wanted to be like them, so that was what I read. One of the earliest novels I can remember reading was Revolt on Alpha C, by Robert Silverberg. It had starships and ray guns and all kinds of other science fictional goodness. I was a nine-year-old boy. How could I not be hooked?

But I didn't just read science fiction and fantasy. I read everything, voraciously. History books and adventure books, horse books and dog books, classics and not-so-classics. In school I became known as the kid that was always raising his hand and class and then saying, "I read somewhere that…"

Because I read, I occasionally knew more about a subject than my teachers. (Sorry, teachers, but that is a hazard of teaching kids to read.) For example, I loved a series of English children books called Swallows and Amazons, which are all about kids sailing. I knew from those books that the "sheet" on a sailing boat is actually a rope that controls the angle of the sail. I had a teacher that told the class that the "sheet" was the sail. Naturally, I couldn't let that stand, and the discussion grew…a little heated. But I'm sure, upon reflection, once she realized she was wrong and I was right, she appreciated my ten-year-old self for setting her straight. Although I admit she didn't say so at the time.

Books transported me to places I could never have gone, real places, imaginary places, might-have-been places and might-yet-be places. They taught me about airplanes, aardvarks, auto racing, astronauts and apples–and that was just the A's.

And somewhere along in there, because I loved reading, I got the notion I'd like to tell my own stories. One reason was that I sometimes couldn't find the kinds of stories I really enjoyed reading. (You, oh most fortunate children, live in the Golden Age of fantasy and science fiction for children and adults; in my day such books were few and far between.) I thought, well, maybe I should just create my own. But I didn't want to write just for myself. I wanted to write for readers: I wanted to tell stories that readers would enjoy as much as I enjoyed the books I loved.

And so, when I was 11 years old, I wrote my first short story, "Kastra Glazz: Hypership Test Pilot." And my Grade 7 English teacher in Weyburn, Tony Tunbridge, did me the great courtesy of taking it seriously: he critiqued it, and didn't just tell me that it was wonderful (which, in retrospect, it really wasn't), he told me how I could make it better.

I've been writing stories ever since. I wrote three novels in high school (and passed them around for my classmates to read: rather brave of me, I think now), and kept writing them until, finally, I started getting them published.

But you know what? I still read. More than ever. Books, blogs, magazine articles, newspaper stories…I can't sit still for more than a few minutes without needing something to read.

Reading led me to be a writer. Reading has led others to be doctors, engineers, scientists, architects, artists, actors. Reading opens up all worlds and all possibilities. It's the foundation of learning, and believe me, you never stop needing to learn. I'm a bit older than any of you–just a bit–and haven't been in school for a very long time, but I learn something new every single day, thanks to reading.

That's the meat and potatoes of why it's important to read. But here's the dessert: reading is fun. Not only that, it's fun that costs nothing, doesn't pollute, rarely results in injury, usually won't get you in trouble, and earns you brownie points with parents and teachers. What's not to like?

Also, as a writer, I really NEED readers. Because otherwise, what's the point?

So I urge you, as personal favour to me, if for no other reason: go forth and read!

September 29, 2011

Test Drive: Ford F150 FX4

Way back in August, just before we headed off on vacation, I was given the opportunity to test drive a Ford F150 FX4…and I haven't written about it until now.

Way back in August, just before we headed off on vacation, I was given the opportunity to test drive a Ford F150 FX4…and I haven't written about it until now.

This is rather embarrassing for someone who, as you may recall from my last test-drive post, has long been a wannabe Car & Driver road tester.

In my defense, I can only offer two excuses: a) Vacation. Drives everything else out of yer head, and b) I am so not the target market for the Ford F159 FX4.

When I wrote about the Explorer I test drove I mentioned that I'm more a car guy, and the Explorer just seemed really big. Well, the F150 seemed really REALLY big. So big I felt like I was lording it over everything else on the road, looking down on the little people in their HumVees and Cadillac SUVs.

This is not, I hasten to add, necessarily a bad sensation. In fact, I rather enjoyed it. It's great to be able to see over almost everything in front of you. One thing I hate about other people driving big vehicles is that they block my view of the road. Not a problem while I was driving this.

Still, it all seemed a bit much for someone who was just, say, running to the gas station for some milk.

Which brings me to the other reason this isn't really a vehicle I'm the prime target for or probably the best person to review it. Simply, I had nothing to haul. Carrying around a laptop case (worse, a netbook case) in a Ford F150 is like using a Saturn V rocket to throw a ball into the air. (OK, that's slightly hyperbolic, but only slightly.) I should have been hauling huge chunks of steel, or bales of hay, or logs, or maybe drums of oil. Something that would make good use of the heavy duty suspension and the high road clearance and all the rest of it.

Not only that, even if I had had something to haul, the only place I needed to drive while I had the vehicle was around town. Although admittedly the street in front of our house could use some repair work, it isn't so bad that four-wheel drive was required. And since this was August, not January, there wasn't even any snow to try it out in.

Not only that, even if I had had something to haul, the only place I needed to drive while I had the vehicle was around town. Although admittedly the street in front of our house could use some repair work, it isn't so bad that four-wheel drive was required. And since this was August, not January, there wasn't even any snow to try it out in.

So I felt like I didn't give the pickup the workout you would have to give it to write knowledgeably about its no doubt spectacular capabilities as a heavy-duty workhouse.

But what I can say is that it drove easily, it rode comfortably, the interior was nice and I really liked the way the rear-view camera image showed up on the left side of the rear-view mirror.

Also, it was extremely red.

I'm glad I gave it a try. It's not something I can every see myself buying, but for those in the need of a real workhorse that's also a fine-looking vehicle, I'd say it's ideal.

Myself, I think I'll stick to a car.

September 23, 2011

Seeing through someone else's eyes

Whenever I say anything is impossible, I always think of Arthur C. Clarke's First Law: "When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong."

Up until recently, I would have said mind-reading was impossible…but, even though I am neither distinguished, elderly, nor a scientist, it's beginning to appear as if it may not be impossible forever. Why? Because scientists have successfully reconstructed videos of what people have seen, simply by scanning their brain activity.

Sure the resulting video is extremely blurry, but like a singing dog, it's not so much that it sings well as the fact it sings at all that is extraordinary.

The research, led by neuroscientist Jack Gallant at the University of California, Berkeley, follows up on previous research from 2008, when the same team reported it was able to use data from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to determine, with 90-percent accuracy, which of a library of photographs a person was looking at while their brain activity was measured.

Reconstructing video, however, is much tougher. As Gallant points out, fMRI doesn't measure brain activity directly; rather, it measures blood flow to active areas of the brain. Blood flow is much, much slower than the back-and-forth among neurons, and video, of course, is changing all the time, resulting in a lot of back-and-forth.

To get around that, Gallant and postdoctoral researcher Shinji Nishimoto designed a computer program that combined a model of thousands of virtual neurons with a model of how the activity of neurons affects blood flow in the brain. The program allowed them to translate the slow flow of blood into the much speedier flow of information among neurons.

Next, three volunteers, all neuroscientists involved in the project, watched hours of video clips while inside an fMRI machine. Gallant's team built a "dictionary" that could successfully link the recorded brain activity with individual video clips. The computer learned, in other words, that a particular pattern on the screen corresponded to a particular pattern of brain activity.

With their dictionary in place, the researchers gave the computer nearly 18 million seconds of new clips randomly downloaded from YouTube, none of which the volunteers had ever seen. Then the volunteers' brain activity was run through the model, which was told to pick the clips most likely to trigger each second of activity: in other words, to reconstruct the volunteers' video experience using building blocks of random moving pictures.

Say the volunteer saw someone sitting on the left side of the screen. The computer would look at the brain activity, then go to its library of clips and find the ones most likely to trigger that particular pattern—most likely, videos of people sitting on the left side of the screen.

The final videos were recreated from an average of the top 100 clips the computer deemed closest based on the brain activity. The averaging was necessary because even 18 million seconds of YouTube video didn't come close to capturing all the visual variety in the original movie clips. As you would expect, the results are blurry—but still recognizably in the right ballpark, especially in cases where there are people simply sitting and talking to the camera.

Presumably, the larger the library of clips the computer had to draw on, the closer it could come to capturing exactly what the individual had seen…offering the tantalizing possibility of someday accurately playing back another person's visual experience.

The researchers hope to build models that mimic other brain areas, such as those related to thought and reason. The potential, however far down the road it may be, is for nothing less than machines that can read people's thoughts, or even play back their dreams (opening up the fascinating possibility of professional dreamers, whose dreams would be so interesting people would pay to see them, or directors who would only have to vividly imagine their stories to see them on the screen, rather than go to all the trouble of actually filming them).

Sound impossible? Well, maybe. But remember Clarke's Second Law: "The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible."

And if it all sounds like magic—which it certainly does—well, then, remember Clarke's Third Law while you're at it: "Any sufficiently advanced technology," he said, "is indistinguishable from magic."

September 16, 2011

Gait recognition

Twelve years ago, I started a science column with this sentence: "Are you fed up with having to carry 2,762 separate plastic cards in your wallet for buying gas, getting Air Miles, withdrawing money, renting videos and collecting frequent-ice-cream-eater points? Then you'll be glad to hear about biometrics…"

Twelve years ago, I started a science column with this sentence: "Are you fed up with having to carry 2,762 separate plastic cards in your wallet for buying gas, getting Air Miles, withdrawing money, renting videos and collecting frequent-ice-cream-eater points? Then you'll be glad to hear about biometrics…"

More than a decade later, I can't help but notice that I still have 2,762 separate plastic cards (a rough approximation, admittedly). But work continues on biometrics, and a new study describes a promising new way to use biometrics to pinpoint identity: gait recognition.

Biometrics (as I wrote 12 years ago) "is the measurement of tiny differences among individuals for the purposes of identification. Fingerprinting is probably the best known example."

Fingerprinting has been around long enough that everyone knows that each person's fingerprints are unique, which makes their use for identification purposes well-accepted. They also have an advantage in that they're particularly easy to digitize, and hence to search by computer.

The downside to using fingerprints is that they are closely associated in people's minds with criminal investigations, making their use in other arenas (such as requiring people who are cashing welfare cheques to place their finger in a scanner, something Connecticut began requiring in 1997) problematic.

There are other forms of biometric identification, of course. There's the hand scanner, which takes two infrared pictures of a hand, one from above and one from the side, and compares dozens of measurements, including width, thickness and surface area, with a previously stored template. The military has used these for a long time.

Iris scanning is based on variations in shading in an individual's iris, a pattern that is unique to each individual and also (very important) stable over time. Retinal scans shoot a beam of light into the eyeball and record the formation of veins.

Facial recognition involves photographing faces, then analyzing details of the features and their positioning. Voice recognition measures the wave patterns generated by the tone of a person's voice.

Now comes gait recognition. According to a study just published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface in the U.K., footsteps are as unique as fingerprints, and can identify people with a 99.8 percent accuracy.

The method is based on the use of pressure-sensing mats that can record how hard people's feet press against the ground, their stride length, and other aspects of their gait. These mats are already used in orthotics to help diagnose and treat foot problems.

Gait recognition as a method of identification was tested in a study out of Arizona State University last year. Test subjects walked over a large-area, high-resolution pressure-sensing floor. From that information, a computer model of each individual's way of walking could be constructed. In that study, the recognition rate (albeit it with only 11 subjects with different walking styles) was 92.3 percent, with a false alarm rate of 6.79 percent.

The small number of test subjects made it difficult to determine if the method could be used in the real world. In the new study, led by Todd Pataky of Shinshu University in Nagano, Japan, 104 people were asked to walk across a half-metre-long board studded with thousands of pressure sensors. Ten steps per person were recorded, with the sensors registering both how each foot applied pressure to the ground, and how the pressure distribution changed as the person walked.

That information was used to train a computer program to pick out the patterns in people's walks. Out of 1,040 steps recorded, the program incorrectly identified only three.

Pataky told the British magazine New Scientist that, "Even if they have the same foot size, even if they have the same shape, [people] load their feet differently and they do it consistently."

One application, as I noted earlier, could be in airport security. Each person boarding a plane would walk across a similar sensor (they're available commercially for about $20,000 each) to ensure they were who they said they were (assuming, of course, that their particular stride was already in the computer database).

The downside: you have to walk across the sensor barefoot, where thousands have walked before. (Yuck.)

But, hey, we're talking about the airport. In the age of full-body scanners, what's another humiliation more or less?

September 8, 2011

Just-below pricing

I've been toying with the idea of getting a MacBook Air (my old Samsung netbook has just about had the life pounded out of it after churning out half a million words or so, including all of my upcoming book Magebane), and I noticed that the 11-inch MacBook Air is listed on Apple's Canadian site as starting at $999.

I've been toying with the idea of getting a MacBook Air (my old Samsung netbook has just about had the life pounded out of it after churning out half a million words or so, including all of my upcoming book Magebane), and I noticed that the 11-inch MacBook Air is listed on Apple's Canadian site as starting at $999.

Well, at least it's not $1,000!

We're used to seeing these kinds of pricing games. You almost never see a product priced at an even, say, $23; no, it will be $22.99 or $22.98. I've put a couple of my old young adult science fiction books on Kindle. You can currently buy Andy Nebula: Interstellar Rock Star and its sequel, Andy Nebula: Double Trouble, for just $0.99. Why not $1.00? Well…because everyone knows that pricing something just under the next round number somehow magically convinces people that they're getting a bargain.

There's just one problem. According to Robert Schindler, a professor of marketing at the Rutgers School of Business-Camden, who has been studying this marketing strategy for years, it doesn't always work.

In fact, sometimes it can backfire: "When consumers care more about product quality than price," he says, "just-below pricing" (as this technique is called) "has been found to actually hurt retail sales."

Schindler conducted a meta-analysis of more than 100 different studies of just-below pricing and says that, yes, it does work: people really do perceive, subconsciously, a big difference in price between $19.99 and $20, and think they're getting a bargain. The effect is actually greater than the perceived difference between something priced at $25 and $20, even though $5 is rationally a much greater savings than one cent.

The reason seems to be that people pay a disproportionate amount of attention to the leftmost digit in prices: that's the one that determines whether an object is seen as affordable.

A study published in the Journal of Consumer Research in 2009 bore this out. Kenneth C. Manning of Colorado State University and David E. Sprott of Washington State University conducted a number of experiments to see how people determined affordability. In one, they asked participants to consider two pens, one priced at $2 and the other at $4. Decreasing either price by a single cent lowered the leftmost digit by one.

They found that when the pens were priced at $2 and $3.99, respectively, 44 percent of the participants chose the higher-priced pen. But when the pens were priced at $1.99 and $4, only 18 percent chose the higher-priced pen.

"The larger perceived price difference between the pens when they were priced at $1.99 and $4.00 led people to focus on how much they were spending and ultimately resulted in a strong tendency to select the cheaper alternative," the researchers wrote.

In another experiment, the researchers compared two round prices (such as $30.00 and $40.00) to two just-below prices ($29.99 and $39.99). They predicted that people would perceive the two round prices as more similar to each other than the two just-below prices, and that as a result, people would focus less on how much they were spending with the round prices…which proved to be the case: with round prices, a relatively large percentage of people chose the high-priced option, a percentage that dropped dramatically when they were presented with the just-below prices.

But Schindler, who has just completed a textbook on pricing strategies, says his meta-analysis of studies in the field shows that just-below pricing can have an unexpected downside: it can give the impression that an item is of poor or questionable quality, and thus should be avoided on luxury items and services or purchases that might be seen as risky.

The example he gives is of a contractor trying to get hired to work on someone's house: the last thing you want is for your price to suggest that you might do a poor job, so it's best to stay away from just-below pricing: keep your bid at, say, an even $10,000—don't knock it down to $9,999.99.

Most of us spend more time shopping than pricing our own goods and services, though, and for shoppers, it's definitely a case of caveat emptor. As Manning and Sprott put it, "Consumers should be aware of the subconscious tendency to focus on the leftmost digits of prices and how this tendency might bias their decision making."

In short, a pig in a poke is still a pig in a poke–whether it's priced at $100 or $99.99.

(The photo: The Dealers' Room at the World Science Fiction Convention in Reno, Nevada, August, 2011.)

August 30, 2011

The Black Death

At this year's World Science Fiction Convention, in Reno, Nevada, the Hugo Award for best science fiction novel of the year went to Connie Willis for Blackout/All Clear (Spectra Books), in which historians from the future, researching the London Blitz, find themselves trapped in it.

Willis's time-travelling historians have featured in previous books, notably Doomsday Book., where the focus of the research is the Black Death. Willis's depiction of its horrifying human toll of the Black Death has stuck with me for years.

Erupting in 1347 in China, the Black Death spread through the Middle East to Europe, where it killed 50 million people—one third of the population.

I've always thought "everyone knows" that the Black Death was a version of bubonic plague. But as is often the case in science, not everyone believes what everyone knows.

Bubonic plague is caused by a bacterium called Yersinia pestis, and analysis of ancient DNA (aDNA) has certainly revealed Y. pestis in plague victims from the Black Death in the past.

Nevertheless, discrepancies between the symptoms of the Black Death and those of more recent outbreaks of plague, plus the difficulty of accurately analyzing ancient remains for the presence of Y. pestis, have led some to suggest that perhaps the Black Death was caused by something else entirely: that it could have been a hemorrhagic fever, a la Ebola, or even something completely unknown.

In 2010 a team of anthropologists from Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, analyzed dental pulp or bone samples from 76 human skeletons excavated from "plague pits" in England, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, and claimed to "unambiguously" show that Y. pestis did indeed cause the Black Death.

They went looking through the ancient DNA for traces of Y. pestis, and found a Y. pestis-specific gene in 10 specimens from France, England and the Netherlands. They didn't find it in the specimens from Italy and Germany, but they had another weapon in their scientific arsenal called immunochromatography which revealed the bacteria's presence.

A more detailed analysis revealed that, rather than belonging to one of the two known strains of Y. Pestis, dubbed "orientalis" and "medievalis," their samples belonged to different, older forms.

Of those two, one type appeared to have similarities with types recently isolated in Asia, while another, they said, probably no longer exists today.

Some scientists remained skeptical…but at least some of those skeptics have now been convinced by a brand-new study by researchers from Canada's own McMaster University.

Hendrik Poinar, an evolutionary geneticist and member of McMaster University's Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, graduate student Kirsti Bos, and collaborator Johannes Krause of the University of Tubingen studied the DNA of 109 human skeletons buried in 1349 at East Smithfield, a mass grave site for London victims of the Black Death, and another 10 buried at St. Nicholas Shambles, a site that pre-dates the Black Death.

They used a clever new technique: with DNA from a modern strain of the plague, they made a molecular "probe" that would bind to DNA from Y. pestis. Then they attached a magnetic chip to the probe, which allowed them to use a magnet to later retrieve the probes from the bone samples.

They found that the samples from East Smithfield did indeed contain bacterial DNA belonging to a strain of Y. pestis—and, indeed, a strain that doesn't exist today. Nor was it present in teeth from the skeletons buried in the Shambles, prior to the Black Death.

Two members of the team had previously argued that Y. pestis was not the cause of the Black Death: this evidence convinced them. It also convinced Tom Gilbert at the University of Copenhagen, another skeptic of previous research. "What makes this work stand out is its very clever approach," he says.

Gilbert and Poinar alike believe that this technique may allow scientists to uncover the full genetic sequence of the strain of Y. pestis that caused the Black Death, explaining why it was so virulent, how it evolved…and helping scientists predict if any similarly devastating strain might appear in the future. It could also help researchers uncover the secrets of other ancient pathogens.

But the best news of all is that the Black Death bacterium appears to be extinct.

Having read Connie Willis's Doomsday Book, I find that particularly comforting.