Chip Jacobs's Blog, page 4

May 15, 2020

I’ve waited long enough: the story of the Man in the Light

The baseball cracked off the bat, vanishing into the smoggy, gray sky over east Pasadena’s Eugene Field Elementary School. Squinting and craning for it, I became a boy obsessed, a boy determined to make this pop-up fly ball his playground conquest. When the spinning white dot finally reappeared, growing in dimension every second, adrenaline was my master.

Only dibs needed to be called.

“I got it—I got it!” I hollered that day in 1970, waving my arms like I’d seen Los Angeles Dodgers centerfielder Willie Davis do frequently on TV.

Then again, he was a professional athlete who brandished a mitt. I was an impulsive third grader trying to grandstand for my recess chums by catching a high velocity object with my bare hands.

So, I got it all right—right in the bridge of my nose.

The wicked thump was a horse kick to the face. Seconds elapsed before I realized what’d happened, before I peered down at my T-shirt transmuting from lily-white cotton into an expanding Rorschach of bright red.

My nose wasn’t bleeding. It was an unstoppable faucet. I nearly fainted on the blacktop.

At the school infirmary, the nurse handed me a tissue to staunch the bleeding. Soon, I was in my mom’s pale-blue Ford Mustang, too shaken to guilt her into a therapeutic trip to Baskin Robbins for a double-scoop cone.

“Am I going to die?” I asked her, eyes normally full of mischief clouded with fear. “Do I still have enough blood in my body to live?”

“Don’t be silly,” she replied gently. “You just had a little accident.”

Little?

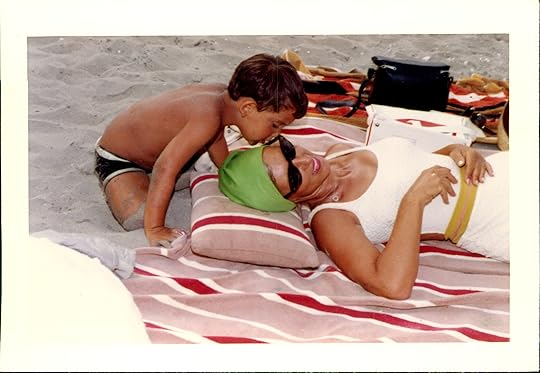

Me probably asking for ice cream a few years before my experience.

Me probably asking for ice cream a few years before my experience.That night, in the lower berth of my cozy bunk bed, I shut my eyes, repeating her guarantee that I’d wake the next morning.

As it were, I wouldn’t sleep through the night.

When “it” happened, I wasn’t facing my turquoise-painted wall, which I normally did to avoid eyeballing the monsters—Dracula, Frankenstein, itinerant werewolves—that I sometimes imagined strolled past my bedroom. I was turned outward.

At roughly 2 a.m., an oval bubble of pristine, white-gold-ish light from the corner of the room summoned me out of a cavernous sleep. Or, more accurately, yanked me out of it.

Inside this sparkling incandescence unlike anything plugged into a socket was the bearded, blue-eyed figure that starred in children’s Bible books. The man in the light wore his customary garb—white robe, burgundy sash—and a penetrating expression of bottomless understanding. His sandaled feet levitated above the shag carpeting, which I’d stained endlessly with Welch’s Grape Juice and Elmer’s Glue. He bunched two raised fingers together. Peace.

I lifted myself off the pillow and blinked, certain I was dreaming. Strange. He was still there. I blinked again: He remained. I shook my head in a double-take simulation of cartoon characters shocked to their stenciled gourd.

Yet he remained, aglow for thirty-odd-seconds, with just my Bugs Bunny stuffed animal bearing witness. To this day, I remember how the spectacular light haloing him was bright without being blinding, alive and self-generated, its crystalline particles rotating in place like twinkling diamonds.

My pajama top beat to my sledgehammering chest as I galloped into my parent’s darkened bedroom, simultaneously ecstatic and petrified, after He dissolved. Deep down I knew that light was magical.

“Mom, mom!” I stuttered, rocking her motionless shoulder. “Jesus—he was in my room. Come look.”

Well, she didn’t. She grinned dopily, mumbling, “I believe you.”

After a comfort hug, she fell back to sleep, as if this presence warranted no urgent inquiry. Disappointed, I tiptoed back to my room, imploring my visitor that one trip tonight was enough for this boy.

But questions; yeah, I had a GI Joe lunchbox of them for my mom, an ex-beauty queen turned mercurial social butterfly and unflinching believer. How, I posed the next morning, did Jesus creep into our house? Where did he travel next? Did his robe have pockets? Could telescopes pinpoint his address?

Today, her answers escape me. I do recall her explicitly warning me not to spill a word to anyone, lest they misunderstand, or think I was a liar. Consider his appearance “a gift,” she advised.

“Why did he visit me?” I followed up. Why, after all, was my favorite word.

“You’ll discover that in due time,” she answered.

I must’ve been displeased by her vague explanation, because she volunteered her own ghost story. My jaw plopped open.

Days after her father’s untimely death (this, fourteen years before I was born), she claimed that he’d returned. As from beyond. She said that he roused her from the foot of her bed, engulfed in light, reassuring his heartbroken daughter all was well.

After another round of my rat-a-tat questions, she told me to go play.

Of course, I was an eight-year-old child digesting all this absent any context. I had little inkling then religion was emotional TNT between my mom and Caltech-educated atheist/agnostic father; that they coexisted in a prickly détente in which my two older brothers and I could celebrate Easter and Christmas so long as my mom didn’t flaunt their mystical underpinnings. Even brief mentions of our baptisms ignited closed-door shouting matches everyone could hear.

No wonder my mom taught me the Lord’s Prayer and Memorare at night in hushed tones.

It was my father to whom she hoped I’d never say anything about that night.

Restless curiosity propelled me through college, and then a career as a journalist, where I adored connecting dots and unearthing secrets.

As for my own one, I was circumspect but not silent about the man in the light. Over time, I confided my experience to a handful of people, especially when I believed they could use some inspirational nourishment. Most listened earnestly, courteously—before suggesting that my traumatized brain had conjured up a soothing, hologram Jesus. By this logic, evolution was to thank for what I saw in my room, not any creator psychically linked to his creations. Afterwards, I usually regretted saying a damn thing, identifying with folks in the same prickly limbo after encountering U.F.O.s or other supernatural events. We need, for ourselves and our moral latch on the world, to proclaim what happened, and yet to do so risks silent pity at best and outright mockery at worst.

A knee-jerk culture quick to slap scientific denunciations and Twitter memes on any phenomena that fails to reach its vague standards beats you into silence.

Over time, It left me wondering about delusion. Was it me, for recounting the moment that’s lost none of its vividness and beauty over the decades, or doubters who believe God is either a fairytale or a harried divinity with no time for a taxi-door-earred, little kid panicked about how much blood his anatomy could spare?

Lung cancer snatched my cigarette-puffing mom in 2008. My special-needs, middle brother, Peter, followed her unexpectedly in 2012. Their departures isolated me with my oldest brother, Paul, and a cantankerous, ailing father who saw light merely as measurable photons.

By now, I wasn’t the same Chip. I was riveted (okay, fixated) with seeing behind the earthly veil. Near-death experience, past-life memories, reincarnation; you name it I devoured books, articles, videos and whatnot chronicling them. I could dazzle you about the celestial odysseys of the clinically brain-dead, and the child who remembered dying near Japan as a U.S. pilot in World War II. My father, who had been scarred as a Depression-era child, had judged every bit hogwash.

My zeal about the blurry boundary between life and the afterlife continued to perplex my friends, who wondered if I was squirming with my own mortality—logic that periodically inhabited me, too.

That was before a fateful day in summer 2018.

At a family wedding, I found myself sitting in a pew next to a woman whom I hadn’t seen in years. Maria was the sweet, reserved wife of a handyman-carpenter who’d long worked for my father’s real estate business. Unprompted, she told me of an apparition. (Looking back, people always seems to be doing that.)

On the first anniversary of my father’s passing, at nearly ninety-eight, Maria claimed she’d had a barnburner of a dream. In it, my dad had reappeared before her, looking more vibrant than she’d ever seen him in this plain. The visiting entity asked her to deliver a message.

He wanted Maria to speak to Paul, who didn’t share my particular Eastern-influenced Christianity, and was more distraught by our father’s demise than me. Tell him not to anguish, our restored parent said, for he now lived not in an urn at Forest Lawn Cemetery but in a locale electric with spirits.

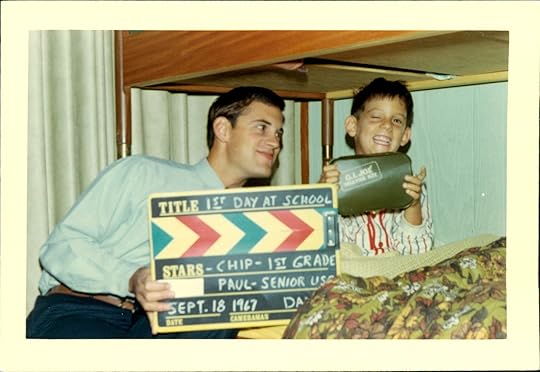

It was in this bunkbed where my celestial gift awakened me.

It was in this bunkbed where my celestial gift awakened me.I asked Maria if her sleep visitor mentioned me. No, she said.

“That’s definitely my dad,” I replied with a teary chuckle. “Definitely.” Paul, still his favorite child, needed that consolation.

Before that day was over, I had my own awakening: what happened to me in 1970 wasn’t an aberration. It was part of an intriguing family club, where departed relatives visited the living in their dreams and darkened bedrooms.

It just so happened then—or was it?—I was writing my first novel, historical fiction swirling around construction of my hometown’s Colorado Street (aka “Suicide) Bridge during the Progressive Age. I decided the time had come for me to salt in what I learned that night. That there is no death—that the Grim Reaper isn’t as a collector of souls who takes one to extinction. He’s a corny, cloak-wearing fraud weaponized over the millennia by kings, popes, demagogues, and profiteers to keep the fearful masses under their thumbs. So, I took the plunge, filling Arroyo with a natty guardian angel and a clairvoyant dog. My main character, Nick Chance, must die in abject failure so he can live again to get it right.

I did it with the spirit of that cosmic light, because it wasn’t just for me. How selfish, how insecure—how cowardly—I’d been until to allow other people’s blinkered skepticism to keep me from heralding the “gift” that my mother told her wide-eyed boy he’d decipher someday. From now on, the spectral fireworks I felt in my heart, back in my bunk-bed days, will infuse everything I write. Everything I do.

The trajectory of that nose-smashing baseball wasn’t calculated in error.

The post I’ve waited long enough: the story of the Man in the Light appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

March 24, 2020

THE QUEEN AND ME

THE QUEEN AND ME By Chip Jacobs

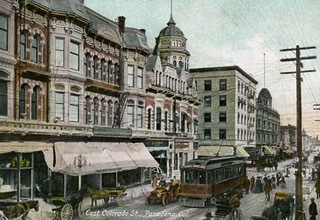

Pasadena’s fabled Colorado Street Bridge consumed eleven thousand cubic yards of cement, each yard weighing roughly two tons, during its lengthy—and sometimes harrowing—construction at the onset of the automobile era in 1912 and 1913.

During construction of this historical novel, there were points when I felt like one of its hefty, Beaux-Arts columns were strapped around me.

The structure still curving over the Arroyo Seco, you see, isn’t only an ode to bravura engineering of the Progressive Age, when steel-reinforced concrete heralded a modernization kick soon to remake cities, architecture, and this futuristic concept known as freeways. The bridge rested in the same vicinity many of my ancestors have resided in since my maternal grandfather, Hollywood musician Lee Zahler, relocated here from New York’s Tin Pan Alley in the early 1920s.

Given that familial connection—and the edifice’s split personality as both a noir-ish beauty emblematic of Pasadena’s grandeur and one of the most blood-soaked places in the San Gabriel Valley—penning a historical novel about the bridge wouldn’t be, as they once said in the day, duck soup. On the contrary, it loomed as a weight-bearing excursion through a minefield. Nobody calls the roadway that helped braid Los Angeles’ two great valleys together by its formal appellation. They call it “Suicide Bridge” on account of the more than 150 souls who’ve leapt to their deaths from its creamy-gray ledges.

Nonetheless, I’d been mesmerized by this bridge—arguably Pasadena’s foremost beauty queen, sorry Rose Princesses—since I was a partying, girl-crazy prep high school student. On the night I crumpled the back of my parent’s Pontiac Grand Safari by stupidly backing into a buddy’s car in the parking lot below her, I swear I could feel the queen staring down at me, as though she already knew we’d enjoying a literary rendezvous later.

It wasn’t a simple journey to her. All I knew, as a former journalist and non-fiction author, was that my maiden stab in fiction would somehow involve a quixotic dreamer and a rascally dog able to occasionally read his companion’s oft-distracted mind. The spark for that concept shared my last name, just not my identity. It was my big brother, Paul, who scolded me that I was squandering my unrelenting sarcasm and affection for irony

and absurdity by genre jumping, from biography to environmental to true crime in the non-fiction universe. Go with your nature, he said, and your love of the pureness of dogs. What’s annoying at family get-togethers might appeal to certain readers.

Not long after, in the course of freelancing an unrelated topic, I stumbled across an afterthought mention in a Pasadena coffee-table-type book about a gruesome construction accident that struck the bridge near quitting time on August 1, 1913. Soon I was obsessed about how the bridge saved repeatedly by good-hearted preservationists, the bridge whose romantic sightlines prop up local art galleries and organizations had such tragic

origins. It just goes to show: the best story is the one you never set out to write.

I started kicking up dirt like an unsupervised Labrador, resurrecting details in the microfiche cubbyholes at the Pasadena Central Library and the subterranean stacks at the Pasadena Museum of History. I downloaded old engineering stories that tested the tensile strength of my liberal-arts brain.

What I discovered about the inception of this old gal was juicy—it’s own gas-lamp soap opera rampant with feuds, missed deadlines, intrigue, and scant justice for those responsible for that semi-collapsed arch, which took a trio of innocent men to their demises from more than a hundred feet in the air. The citizenry, back in a time of a lapdog journalism, knew precious little about this strife and secrets, including how the tycoons living in mansions on the Orange Grove Boulevard’s “Millionaire’s Row” influenced the bridge’s design.

A pilot light flicked on in me: this is the backdrop I coveted for my man-dog morality tale.

I probably bought Jeff Bezos a tony, new blazer with the twenty-odd books about the city and general atmosphere I purchased off Amazon. From them and other sources, I saw that turn-of-the-century Pasadena held a constellation of big names I could use: Teddy Roosevelt, muckraker Upton Sinclair, Renaissance Man Charles Fletcher, and Adolphus and Lillian Busch, whose magical gardens of terraced slopes, fairytale huts, and winding paths were once crowned “the eighth wonder of the world.”

Looking back, I realize I’d collected the essential ingredients for a historical novel: romance, parasol-twirling splendor, political trickery, and hidden conflict surrounding a famous bridge infamous today for rampant suicides and ghosts.

But what I was missing could’ve filled a dozen concrete vats. In early versions of Arroyo, my characters were feebly drawn individuals in the thick of either dangerous or entertaining circumstances. My celebrities were gaudy showpieces who played no role in advancing or arresting my protagonist, his suffragette girlfriend or his precocious dog. The bridge itself had nothing to add – a stoic royal indifferent to the escapades created in her name.

Around the time I was about to start writing, my elderly father’s health nosedived, and I used his death as a pretext to delay the inevitable rolled-up sleeves grind. So, I disgorged an overwrought 30,000-word outline instead of a first draft doomed to fail. When I finally produced a miserable second draft, my editor critiqued my book-in-progress as “original,” “fun” and nowhere ready for publication.

He was right. I couldn’t tackle such an important and uber-delicate subject with a tissue- thin storyline where events subsumed the characters’ journeys. And I’d be damned if I was going to make the Colorado Street Bridge’s association with suicide the centerpiece when the better story was the provenance of her dark alter-ego.

A gutless historical novel about my city’s most enigmatic creature: what was I thinking?

It was a return to basics. I buried my nose into writers who’d brought history in Technicolor brilliance: Pete Dexter (Deadwood) and T.C. Boyle (Road to Wellville). I studied how they developed their heroes, black hats, and side characters within the realm of their time. I read John Irving’s latest, Avenue of Mysteries, to decipher how he so effortlessly integrated magical realism into his engaging morality play.

Still, the writing wasn’t as simple as the inspiration I drew from Messrs Dexter, Boyle, and Irving. It was perspiration time – no more Internet distractions, excuse making, or delusions my story would materialize, to quote John Lennon, “on a flaming pie.” I had to accept I’d fail in draft after painful draft, in storylines that tried to be all things to all people, in prioritizing clever phrasing over crisp exposition. And when the sheer tonnage of my ambition put my bone strength to the test, I quaffed Diet Coke and reminded myself that my novel demanded to be about unique characters living fishbowl existences within little-known history.

For four months starting last Thanksgiving, I buckled down like I had on no other book, pushing myself to the brink (while paying for my previous posturing as a future novelist). I made myself a rumor to my family. I forsook weekends, favorite Netflix shows, vacations, and the Pasadena sun. I cut, edited, and revised through flu-bugs and a trigger- finger caused by repeated use of the delete key.

By Easter, I’d lopped twenty thousand words and, with the assistance of my patient editor and understanding publisher, created a storyline far more nuanced and magical than I ever dreamed I could.

Suddenly, the concrete felt a whole lot lighter. I hope I made Pasadena’s weighty queen proud as her un-sought biographer.

Author and journalist Chip Jacobs grew up in northeast Pasadena. He’s written four non-fiction books, and his reporting has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, The New York Times and other well-known publications. Arroyo is his first novel.

Note: this essay, first published on the blog A Writer of History in November 2019, has been slightly amended. Link to the original version: https://awriterofhistory.com/2019/11/...- jacobs/

The post THE QUEEN AND ME appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

March 14, 2020

The Boom that Blew the Petals off the Rose City

Square-jawed and persuasive, developer E.C. Webster, it was said, could’ve sold plots on Mars for a profit. Luckily there was Pasadena of the late-1880s, where Webster’s knack for acquiring properties at “shoestring prices” before reselling them for nifty gains made him a legend.

The dealmaker behind the Hotel Green, the Grand Opera House, and Raymond Avenue’s opening typified a boomtown spirit champing to wring fortunes from the land. And what a spirit it was. Between 1886-1887, a foothill plain known for citrus groves, sheep pastures, and a single saloon transformed into, arguably, one of the hottest real estate markets in America.

Pasadena’s founding fathers in the “Indiana Colony,” who a decade earlier had espoused equitable property division among its members, surely cringed at the frenzied activity. If you had cash, you were cajoled to invest. If you owned a tract, you were wooed (or badgered) to subdivide.

Take the case of O.H. Conger, who accepted a syndicate’s $15,000 offer (about $406,000 today) for his twenty-acre orchard south of Colorado Street in this period. He netted a $5,000 windfall. Craving more, the buyers held an auction they marketed with free train rides, complimentary grub, and a brass band. Though some deemed the event indecorous, seventy-seven of the eighty-seven lots divvied up from Conger’s property sold for a collective $22,000.

The county recorder’s office illustrated this was no fluke. During the “great” land rush, Los Angeles, then twelve-times larger in population, filed 549 subdivision maps. The future home of the Rose Parade submitted seven times more.

Speculators, or “boomers” as were tabbed, seemingly crept everywhere in a town still lacking a charter, reliable water system, or decent bridge across the Arroyo Seco. They and the fifty-three local real estate agencies brokered transactions in Victorian-age offices and on plain sidewalks. They shadowed rivals doing site tours to swoop in once they left. They pounded on homeowners’ doors at midnight dangling can’t-miss sales-contracts. They twisted fancy moustaches, soliciting clients with fountain pens and promises.

Conservative financiers fretted the real estate bubble would burst, but it wasn’t a universal opinion. As the Valley Union wrote with a racial tweak: “Put your money to soak in real estate rather than in a Chinese washhouse.”

Many heeded that siren of temptation. A landowner pestered to sell five acres he purchased in 1881 for $2,000 eventually acquiesced to chop up his parcel. He turned a sixty-fold profit. In another case, a lot at Marengo Avenue and Colorado Street where the First Methodist Church once stood became—what else—a residential subdivision.

One evening, a druggist was compounding medication with a mortar when speculator Johnny Mills rushed into his pharmacy. In his hand was a map displaying a plot that he urged his would-be client to snap up before other bidders the next day. The preoccupied druggist refused to glance at the document, so Mills gestured to a jingling streetcar outside waiting for him to say final chance.

Five minutes later they had an agreement. Shortly after that, Mills represented the pharmacist reselling the plot in a classic flip you’d see today on HGTV.

All told, twelve millions dollars ($324 million now) in deals were transacted in 1887. Weed-strewn lots, forlorn houses, vine-covered bungalows; crumbling shacks—all what mattered was their future worth! Why not, when a $300 parcel on Fair Oaks two years later fetched $10,000?

Years before Old Money Pasadena crystallized on Orange Grove’s Millionaire Row, the nouveau riche lived high on the proverbial hog. Men booked hotels for boozy stag parties and poker games. Others flashed diamonds, rode in fine buggies, and ditched nickel cigars for gold-banded ones.

Amid the feverish wheeling and dealing, bigger investors jumped in ways that expanded Pasadena’s reach. An electric light and power company hung out a shingle. Developments on new streets—Los Robles, El Molino, and Lake avenues— pushed activity eastward. Colorado Street underwent a partial street paving, and welcomed the new Arcade building and fresh shops. To keep pace will all the building, a dirt-streaked tent city to shelter workers popped up in what’s now Central Park.

Then, as quickly as it started, the law of economics prevailed once the market bottomed out. Sellers now dwarfed buyers. Commercial lending slowed to a trickle. Auctions proved duds. Before long, some of those high-flying speculators vanished (probably with investors’ money). One hustler who’d made six figures in real estate resorted to selling peanuts on trains for his keep. Another drove a mule pulling a streetcar.

The way amateur historian J.W. Wood saw it, “The paper fortunes, and some more substantial, had collapsed with amazing celerity, and the dazed and sickened boomers’ dream was over!”

Pasadena’s future might’ve tanked, too, if the banks, whose net assets had plunged by two-thirds, didn’t grant loan-repayment extensions, or aid customers staving off bankruptcy. The population nosedived anyway, as people left behind their failures, only resurging in the next century.

As for E.C. Webster, Wood reported he abandoned his “castles in the air” for a docile life in Missouri.

Unless indicated, monetary figures were not adjusted for inflation.

The post The Boom that Blew the Petals off the Rose City appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

November 14, 2019

Lucretia Garfield: South Pasadena’s Lady in Perpetual Mourning

By the time she settled into her South Pasadena dream house, Lucretia Garfield was a longtime member of an exclusive, bloodstained club uniquely American. Besides her, only Mary Todd Lincoln and Ida Sexton McKinley had stomached the horror of being the widow to an assassinated president.

Though it’d been a quarter century since a deranged stalker with an ivory-handled pistol mortally shot her husband, James A. Garfield, in a Washington, D.C. train station, Lucretia out west continued mourning the loss of her college-sweetheart-turned-spouse. In public, the hollow-cheeked septuagenarian with short, curly locks and austere expressions frequently swathed herself in dark clothes, per Victorian tradition, accenting it with a medallion in James’ honor.

Her moniker: “The Lady in Black.”

The daughter of a carpenter-farmer from Hiram, Ohio, Lucretia never desired that grim legacy. Who would? She was well educated and curious, a onetime teacher reputed to be a more talented orator than even her husband. Neither was born from privilege, and both were gifted thinkers. James, it’s said, solved the tricky Pythagorean theorem (when he wasn’t leading a country still recovering from a decimating Civil War).

Lucretia’s mettle was never open for debate, not after she survived the deaths of two children, a case of malaria, or discovering that her tall, bearded partner—a former college president, Army colonel, and congressman—once had a New York City mistress. As First Lady, the fetching Midwesterner with wide-set eyes studied up on White House history before making two brave decisions: ending the ban on alcohol there but biting her tongue in support of woman’s suffrage, despite her convictions about female empowerment.

None of that mattered after Charles Guiteau, a failed lawyer, preacher, and political hanger-on, shot forty-nine-year-old James point blank on July 2, 1881, as James was setting off for vacation. Guiteau, miffed that Garfield had refused to award him a diplomatic post, self-delusioned that God wanted him to pull the trigger, had carefully planned this execution. Train passengers immediately surrounded the assassin, shouting, “Lynch him!”

Doctors, fearing the twentieth president wouldn’t survive what was actually a survivable wound from a bullet lodged near his pancreas, made things worse by triaging him with unsterilized fingers and instruments. The lead physician continued botching the treatment, over-medicating Garfield with morphine, quinine, and alcohol. When repeated operations searching for the slug failed, the sawbones enlisted Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, to help with a primitive metal detector that Bell called an “induction balance.” The device might’ve pinpointed the slug, if the metal springs of the president’s bed hadn’t caused interference, or if the physician allowed Bell to apply the device on the correct side of Garfield’s body.

Lucretia, nobody’s pushover, wasn’t passive about her husband’s declining condition. She insisted that their family doctor—a woman M.D. she trusted—be allowed to assist the men, and that Congress pay her as much as them for her efforts.

Now riddled with infections and abscesses, the president was ferried to the New Jersey shore in dire hopes the sea breezes could do what the experts failed to: rejuvenate him. They wouldn’t. He died on September 19, 1881, having served for just two hundred days. Nine months later Guiteau, who’d pled insanity, was hanged for his crime.

Sympathetic Americans donated $360,000 for the family’s welfare. For the next twenty- odd years, Lucretia focused on being a parent to her abruptly, father-less children. Still, James occupied the prime real estate in her heart. To honor their joint passion for literature, she added a large wing onto their home outside Cleveland. It became the country’s first presidential library. A fireproof vault held James’ papers.

After Lucretia’s offspring grew, she coveted a change in scenery. So, she contracted for a steep-roofed, open floor-plan-chalet on shady Buena Vista Street in South Pasadena. The architects she selected were distant relatives who knew their way around a blueprint. The Greene brothers were innovators of the head-turning Craftsman-style home.

Lucretia, penny-pinching and opinionated about the design, regularly corresponded from Ohio with Charles Greene. In one reply to her, he admitted being distracted by a birth of a child, whom he confided he thought was “homely.”

“Couldn’t the projection of the second story,” Lucretia asked him in another one of her detail-oriented letters about the project, “be continued just a little in a flat roof underneath the cornice?”

Charles trod gingerly responding. “The reason why the eaves project from the gables is because they cast such beautiful shadows in the bright atmosphere. Of course, if you” desire “to have them cut back,” I’ll oblige.

Before the five-bedroom, shingle-sided house was completed, Lucretia lived in a residence off Orange Grove Boulevard, nexus of Pasadena famed “Millionaire’s Row. May 1903, however, proved she wasn’t just another famous person in a town sloshing with acclaimed astronomers, inventors, artists and “wintering” tycoons. It was that month that Teddy Roosevelt’s train barreled in on a West Coast swing.

The war-hero president was given a whirlwind itinerary. Stops included a trip to the region’s first luxury accommodations, the hill-mounted Raymond Hotel, the Throop Institute of Technology (later-day Caltech), and the Arroyo Seco, where he admonished Pasadena’s mayor to preserve the valley’s natural splendor. Following a rousing speech under a floral banner exalting his successful Panama Canal negotiations, Roosevelt then

paid his respects to the perpetual lady in mourning; some believe it was Lucretia who invited him to Southern California in the first place. “A short visit was made with this noted lady and a toast drank to her by the President,” according to a record of their meeting.

Lucretia must’ve felt honored by his presence, if also rocked by déjà vu; Roosevelt himself had vaulted into the White House after an anarchist murdered his boss, President William McKinley, two years earlier in Buffalo, New York.

In the ensuing years, it was said no major dignitary would depart town without trekking to see the Lady in Black, whose 4,500-plus-sqauare-foot Greene & Greene has long sat on the National Register of Historic Places. In her dotage, she traveled, continued championing Roosevelt, and volunteered with the Red Cross when World War I broke out. It’s not apparent how much, if ever, she sampled the local attractions, be they Rose Parades, Busch Gardens, Clune’s Theater, the Mount Lowe Railway or the Cawston ostrich farm nearby. One can hope it was a sunny coda for her, nonetheless.

Lucretia died in her South Pasadena sanctuary in March 1918— five years after the Colorado Street Bridge accelerated the automobile age, and decades before Jacqueline Kennedy joined her particular dead-husbands club.

The post Lucretia Garfield: South Pasadena’s Lady in Perpetual Mourning appeared first on Chip Jacobs .