Chip Jacobs's Blog, page 2

October 25, 2023

The Brown Air Prequel for our Climate Change World

I was a kid who constantly asked “why,” which I’m sure drove my parents to reach for the ear plugs. Among my first “why’s” was why, in 1970s Pasadena, the San Gabriel Mountains directly behind us continually vanished, especially on broiling summer days? Why was that cough-inducing, eye-watering blanket of gray air rolling at us like a foul-tasting fog from a bad horror flick? Why did adults, who proclaimed to have everything under control, allow this to happen? Because, you know, it felt dystopian, not reassuring. Decades later, those why’s inspired a social history, with fellow author Bill Kelly, about this. The scars still linger, too, as this recent L.A. Times column animating numerous scenes from that book, Smogtown, illustrate. Think of our air-pollution saga as a prequel to the clenching grip of climate change. It’s my fervent hope that someday, this incredible story chronicling the modern world’s first major environmental catastrophe reaches a worldwide screen, if only for the next generation to realize that no disaster is too big, too scary to conquer when people say no more! Today, the Pasadena skies are blue.

https://www.latimes.com/environment/s...

The post The Brown Air Prequel for our Climate Change World appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

January 3, 2022

Chip’s Year in Writing & Creating

From the moment CNN announced in early 2020 that Covid-19 was set to become this century’s first five-alarm pandemic, the old world as we knew it fell away, replaced, sadly and maddeningly enough, by a darker, deadlier epoch leaving us all wondering what the ugly scars of our “new normal” will resemble. (Metaphor wise, it may just be best to avoid any mirrors.) For me, creativity isn’t just what I do. It’s who I am deep inside, and my most reliable bulwark against the glum emotions polluting my otherwise optimistic psyche. So, in the interest of starting anew in 2022, let me be ironic and direct your attention onto the year (or survival scheme) that was 2021 for this Californian.

In March, while I should’ve still been promoting my first novel, Arroyo—which somehow made the Los Angeles Times bestseller list for seven weeks, scooped up an award, and, most importantly, made people curious if their dog was clairvoyant or their favorite bridge alive—I opted to confront my dissatisfying past. Or, to articulate it another way, I rewrote my 2012 book about a freaky Southern California murder triangle into a more suspenseful, true-crime-y tale. Much to my relief, The Darkest Glare: A True Story of Murder, Blackmail and Real Estate Greed in 1979 Los Angeles, was both critically and commercially well-received. On the literary hustings, I penned essays about it; one was for CrimeReads (about how serial killers of the seventies adopted local freeways and their cars as bloody accomplices) and another about my unintended voyage into this genre. Of all the critiques of the book, the LA Review of Book’s stands out for its insight. I’m also pretty dang fond of the book trailer.

In March, while I should’ve still been promoting my first novel, Arroyo—which somehow made the Los Angeles Times bestseller list for seven weeks, scooped up an award, and, most importantly, made people curious if their dog was clairvoyant or their favorite bridge alive—I opted to confront my dissatisfying past. Or, to articulate it another way, I rewrote my 2012 book about a freaky Southern California murder triangle into a more suspenseful, true-crime-y tale. Much to my relief, The Darkest Glare: A True Story of Murder, Blackmail and Real Estate Greed in 1979 Los Angeles, was both critically and commercially well-received. On the literary hustings, I penned essays about it; one was for CrimeReads (about how serial killers of the seventies adopted local freeways and their cars as bloody accomplices) and another about my unintended voyage into this genre. Of all the critiques of the book, the LA Review of Book’s stands out for its insight. I’m also pretty dang fond of the book trailer.

In May, the culture site SHOUTOUT LA ran a feature about why I became a writer, which allowed me to dredge up my own personal Independence Day (think screaming match with a parent) and to get photographed with my puppy and Stratocaster in my beloved horse head.

I checked off a box in June that’d been empty since I was a teenager dreaming of writing for Rolling Stone magazine. I contributed my inaugural piece of music criticism in my admittedly fanboy-ish essay about one of my desert-island bands: Squeeze. The breezy article, entitled “My Favorite Place,” was included in the anthology Go Further: More Appreciations of Power Power. If you think you know this superb group from 80s radio hits like “Tempted” and “Black Coffee in Bed,” you need a deep dive into the genius of Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford. You’ll come away humming, as well as cheesed off that Donovan is in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame with Squeeze on the outside looking in.

Speaking of essays, the one exponentially more important than any of the above remains my long-time-in-coming piece about a high-fly baseball that whacked me in the nose as a little boy, and then brought the Divine into my room. Limited human that I am, I coined it The Man in the Light. If it’s the last thing you ever read from me, let this be it, and then Let It Be.

I wrapped up the screwed up year by optioning the book I left daily journalism to write, a biography of my maternal uncle called Strange As It Seems: the Impossible Life of Gordon Zahler, to the talented, energetic folks at Mercury Media. The hope, with this and some of my other books, is to turn them into a streaming series. Cuz, what’s life on this topsy turvy third rock from the sun, without a screen?

The post Chip’s Year in Writing & Creating appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

Chip’s Year in 2021 Writing & Creating

When CNN announced in early 2020 that Covid-19 was set to become a border-jumping pandemic, the old world as we knew it fell away, replaced, sadly and maddeningly enough, by a darker, deadlier epoch that leaving us all wondering what the ugly scars of our “new normal” will resemble. (It just be best to avoid any mirrors.) For me, creativity isn’t just what I do. It’s who I am deep inside, and my most reliable bulwark against the glum emotions polluting my otherwise optimistic view of things. So, in the interest of starting fresh, let me be ironic and direct your attention onto the year (or survival scheme) that was 2021.

In March, while I should’ve still been promoting my first novel, Arroyo—which somehow made the Los Angeles Times bestseller list for seven weeks, scooped up an award, and, most importantly, made people curious if there dog was clairvoyant or their favorite bridge alive—I opted to confront my dissatisfying past. Or, to articulate it another way, I rewrote my 2012 book about a freaky Southern California murder into a more suspenseful, true-crime-y tale. Much to my relief, The Darkest Glare: A True Story of Murder, Blackmail and Real Estate Greed in 1979 Los Angeles, was both critically and commercially well-received. On the literary hustings, I penned essays about it: one was for CrimeReads (about how serial killers of the seventies adopted local freeways and their cars as bloody accomplices) and another about my accidental, unintended voyage into this genre. Of all the critiques of the book, the LA Review of Book’s stands out for its insight. I’m also pretty dang fond of the book trailer.

In March, while I should’ve still been promoting my first novel, Arroyo—which somehow made the Los Angeles Times bestseller list for seven weeks, scooped up an award, and, most importantly, made people curious if there dog was clairvoyant or their favorite bridge alive—I opted to confront my dissatisfying past. Or, to articulate it another way, I rewrote my 2012 book about a freaky Southern California murder into a more suspenseful, true-crime-y tale. Much to my relief, The Darkest Glare: A True Story of Murder, Blackmail and Real Estate Greed in 1979 Los Angeles, was both critically and commercially well-received. On the literary hustings, I penned essays about it: one was for CrimeReads (about how serial killers of the seventies adopted local freeways and their cars as bloody accomplices) and another about my accidental, unintended voyage into this genre. Of all the critiques of the book, the LA Review of Book’s stands out for its insight. I’m also pretty dang fond of the book trailer.

In May, the culture site SHOUTOUT LA ran a feature about why I became a writer, which allowed me to dredge up my own personal Independence Day (think screaming match with a parent) and to get photographed with my puppy and Stratocaster in my beloved horse head.

I checked off a box in June that’d been empty since I was a teenager dreaming of writing for Rolling Stone magazine. I contributed my inaugural piece of music criticism in my admittedly fanboy-ish essay about one of my desert-island bands: Squeeze. The breezy article, entitled “My Favorite Place,” was included in the anthology Go Further: More Appreciations of Power Power. If you think you know this superb group from 80s radio hits like “Tempted” and “Black Coffee in Bed,” you need a deep dive into the genius of Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford. You’ll come away humming.

Speaking of essays, the one exponentially more important than any of the above remains my long-time-in-coming piece about a high-fly baseball that whacked me in the nose as a little boy, and then brought the Divine into my room. Limited human that I am, I coined it The Man in the Light. If it’s the last thing you ever read from yours truly, let this be it, and then Let It Be.

I wrapped up the year by optioning the book I left daily journalism to write, a biography of my maternal uncle called Strange As It Seems: the Impossible Life of Gordon Zahler, to the talented, energetic folks at Mercury Media. The hope, with this and some of my other books, is to turn it into a streaming series. Cuz, what’s life on this topsy turvy third rock from the sun, without a screen?

The post Chip’s Year in 2021 Writing & Creating appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

December 24, 2021

At Christmas, “It’s A Wonderful Life.” In 2022, hopefully it’ll be a series about a life as Impossible as it is Strange!

The post At Christmas, “It’s A Wonderful Life.” In 2022, hopefully it’ll be a series about a life as Impossible as it is Strange! appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

July 30, 2021

My Fantastic Place – An Essay

Chris Difford, Glenn Tilbrook: your music is my joy machine. Now cough up $500.

Let me explain on why you owe me. On college party nights my junior year, friends would cram into my boxy, stucco apartment for our peculiar brand of artistic appreciation. Once properly pie-eyed from the intoxicants at hand, we’d select our favorite song, assume a handstand, and then allow pals to hoist us up to the ceiling to “moonwalk” upside-down. While none of us pretended to be a 180-degreed Michael Jackson, dirty heels were imprinted quality rock — the Police, U-2, Cheap Trick — blaring through my Sony stereo speakers.

I, however, only inverted myself for you.

Squeeze was the sound I’d been waiting for from the black hole left by John Lennon’s murder and the shallow onslaught of hair-metal. When “In Quintessence” hit that record needle, I went up. Speedy guitar paired with mordant lyrics, about a blowhard adolescent with a pretend girlfriend ignited something in me.

He smokes himself into double vision

Leaves his mind on indecision

Thinks he’s invented imagination

Says that god is some relation

You know who didn’t have any imagination? My tightwad landlord, who at semester’s end eyeballed white ceiling tiles mucked like a mosh pit and declared that I wouldn’t be getting back my security deposit. So, thank you for that.

And bless you for everything else.

For forty-odd years, Squeeze has remained one those mystifying talents whose exceptional catalogue many Americans pop connoisseurs somehow overlooked. Was it because, like The Kinks before them, their feisty independence, their hunger to experiment in the sonic laboratory, their refusal to prostrate themselves to label A&R men made them slippery to pigeonhole? Or, perhaps they were just the right band at the wrong time.

Think about them as a National Geographic special might. Squeeze’s dominant characteristic would be Chris and Glenn singing in octave-apart voices that are somehow familiar and always infectious. Its natural habitat: the pebbly streets and sandy roads of England from which they mined “kitchen-sink dramas” that make you laugh, weep, or simply marvel how they pulled it off. Its growl: Telecaster-fueled arrangements that know when to showcase six-string chops and when to recede. Zoological superpower? Easy. The ability to produce a lightness of being in those who encircle it for pleasure.

I was in the crowd at an Orange County amphitheater to see them after graduation, knowing that their precocious success had thrust them so close to the sun that they’d had to reconstitute after dissolving. I cared little of melted wings, hearing, on one stage, music pulsing with New Wave synthesizers and nods to Elvis, rockabilly-beats and exotic guitar hooks that’d have Jimmy Page a smidge green. Squeeze’s, oft-sardonic lyrics about romance were just as profound as its styles was versatile, too. When they crooned “if I didn’t love I’d hate you,” I grinned, because that’s how I felt about the mercurial, brunette girlfriend next to me that evening.

Listening then, after seeing so many performers who filled set lists with libidinous and macho themes that disclosed little about the human condition, was a reminder of the brawn of pithy, tactile descriptions. In the elegiac “Vanity Fair,” there’s the dropout who “paints her nails on the bathroom scales.” In the giddy “Piccadilly,” you smell the yellow curry en route to fireplace nooky. In fan favorite “Up the Junction,” you wince for the man who lost everything after “the devil came and took (him) from bar to street to bookie.” In “Revue,” you giggle as the boys skewer a nose-picking, D-list TV host in his “dickie bow ties.”

***

The best pop songwriters you probably only recall from their radio hits or MTV videos were spawned by Chris’ magnificent lie. With fifty pence he swiped from his mother’s purse, he posted an ad in a London shop window. Wanted: guitarist “into” the Beatles, Small Faces, Glenn Miller, and others “for (a) band with record deal and touring.” When a younger, shoeless teen in pink trousers turned up about the solicitation, he found that there was neither an established group nor sealed contract. But why quibble when you’re a match introduced to kindling?

Chris, nineteen, was jet-black haired and shy behind his cockiness, a once chubby kid with dyslexia, imaginary friends, a knack for poetry, and a gypsy’s prediction he’d discover happiness through music. After reading a Pete Townsend interview about the globetrotting rockstar life, he decided the gypsy was right. Glenn, with his long nose and slight lisp, was a more extroverted persona and the organic musician between them. Like Chris, he was also a minor rebel (though never a petty criminal). He’d been booted out of school for refusing to shear his hippy-long blond locks. Chris first noticed him sitting in a flower bed playing guitar like a “beardless Jesus.”

The working-class boys united by musical sensibilities and older brothers with health issues penned a hundred and thirty-seven songs in a flash flood of creativity in 1973 and 1974. Frequently, they wrote in all-nighters pungent with candles, weed, and ambition. As the pop-rock world slobbered over Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and Band on the Run, the fresh-faced lads were chiseling their future. A future where they’d sell out Madison Square Gardens, earn a Grammy nomination, and appear on “Saturday Night Live” and “Late Night with David Letterman.” A tomorrow where they’d become an English heritage act, the subject of a BBC documentary, and count Elton John, Paul McCartney, and Dave Edmund as enthusiasts.

Two became one in their songwriting ritual. Chris would scribble lyrics on notepaper, sometimes without lifting pen from pad, and leave them for Glenn. He’d vanish for days or weeks, and then, like a hermit Svengali, slip his much fussed-over arrangements on a cassette under the door for his partner’s delighted ears. Miles Copeland, their first manager, realized they could be huge.

Initially, they performed originals and covers, playing for beer money. They saw contemporaries in Dire Straits and regarded the Sex Pistols as annoying. Rounding out their lineup was now the effervescent Jools Holland on piano and keyboard, the resourceful Gilson Lavis on drums, and the first of several bass players. John Cale, formerly of the Velvet Underground, produced their maiden album by pressuring them to lean into punk rock. While they untucked shirts and affixed clothespins for his benefit, it was an unnatural fit for pop rock troubadours who tilted New Wave with a melodious ethos. Shazam! In “Take Me I’m Yours,” a marching, synchro-beat propels a traveler journeying across the desert toward belly dancers on a tired camel. Deejays and younger audiences hearing their original sound thirsted for more.

Their first US tour wasn’t exactly screaming girls and popping flashbulbs, just the same. At their debut gig, they jammed before an audience of a man and a dog. By the second set, the dog was gone. Oh, well: they traveled in a van, gelling and growing, with Lavis doing his wild-man Keith Moon impression. Their second album, Cool for Cats, reflected musical growth hormone. In “Goodbye Girl,” the repeating keyboard mimics the quixotic heart of a man who awakens from a one-night stand, “on the lino,” with a woman who stole him blind. While Glenn was the Squeeze’s front man on vocals and guitar, Chris, who played rhythm, sang the title song in a gravelly, cockney rasp. Seamlessly, heightened with narrative storytelling that belied his youth, he transitions from cowboys and Indians to his own life as a local celebrity who fraternizes with villains and groupies, the later of whom gave him “a nasty little rash.”

Argybargy, their follow-up, better defined Squeeze in the music-verse as more eclectic than The Cure, less abstract than Depeche Mode, and, arguably, as reliably toe-tapping as Jeff Lynne’s ELO. There were rockers like “Pulling Mussels (From a Shell), which explodes out of the chute, and “Another Nail in My Heart” with its footfalls riff and silky, almost whimsical lead. Deeper in was “Vicky Verky,” a bubble-gum-fast ditty exploring forbidden love and abortion, and the boogie-woogie of “Funny How It Goes” about hitting on “champagne women.” Heard live, you’d swear that not only was the entire band playing on speed but the song themselves had dipped into the rainbow diet pills.

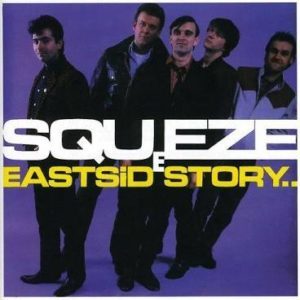

Then drumroll to legend status. The record that Rolling Stone touted as one of the best albums of the decade, the record I wore into vinyl exhaustion, was 1981’s East Side Story. Here, Squeeze smashed its mics through the walls frowning on power-pop genre-hopping. The album gushed with blustery youth (“In Quintessence”) and hummable, blue-eyed seduction (“Tempted”); it evoked female depression (Woman’s World”) about a housewife so unfulfilled by her “shiny new appliances” that she can barely stagger home from the bar. The sleeper is the tear-jerking, country ballad “Labelled with Love,” told with the tenderness of a novel in which the protagonist reflects back on a halting life of loss. In this case, it’s an arthritic widow returning to her native England from the Texas prairie amid the ruins of alcoholism.

She unscrews the top off from her new whiskey bottle

Shuffles about in her candle lit hovel

Like some kind of witch with blue fingers and mittens

She smells like the cat and the neighbors she sickens

Produced by Elvis Costello, East Side Story was a revelation, a comet streaking across the Top-Forty sky. But hen something dreadful happened: invocation of the much-coveted but always hazardous B-word. Rolling Stone dubbed Difford and Tilbrook “the next Lennon and McCartney,” with other critics piggy-backing onto the comparison. As soon became evident, it’d be millstone by the ultimate flattery. Mortals assured they were gods.

On cue, egos bloated, ears were whispered into, and coke vials overflowed their rims. As Chris later admitted, band members started rowing in different directions after this heady correlation. Yes, he sketched urban scenes and quirky people with uncommonly literate observations. But where the Beatles blossomed from love-song-focused mop-tops to path-breakers exploring everything — taxes, loneliness and psychedelic hallucinations, serial killers and universal love — Chris remained in his own detached headspace. Rather than including “Chairman Mao” or a “Billy Shears” character, he focused on self-demons wrestling with survival, addiction, infidelity, and, much later, in “Please Be Upstanding,” erectile dysfunction. Sure, Glenn’s voice resembled Paul’s in pitch and ability to modulate, but his rangy musicianship was as much influenced by his idols Jerry Garcia and Jimi Hendrix as George Harrison’s.

The world craved the next Fab Four, however it got it. Whatever the collateral damage.

Squeeze, dizzied by the parallels to world-changers, fried by the tour-record-tour-record drudgery, sallied forth, brave as ever. But where Magical Mystery Tour sounded like the sequel to Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band, Squeeze’s next albums were never as wall-to-wall bravura as East Side Story. Which isn’t to suggest that they were sputtering on fumes. “King George’s Street” is a marital split, expressed in power chords and emotion, through the eyes of children. In the brassy “Hourglass,” they bagged their biggest US hit. “Melody Hotel,” a twangy takeout about a family man who abused prostitutes, would’ve been an ordinary group’s encore sensation.

Before splitting up again as fissures widened between ever-creative, if stubborn Glenn and fragile Chris, who’d previously bailed on a US tour, self-medicating inner-pain with vodka, powder, and isolation, Squeeze’s tenth album sparkled. It just gleamed in 1993 as grunge-rock overtook the airwaves. In the blazing “Third Rail,” the antihero gives the bottle choking him its walking papers. “It’s Over” is an acoustic-guitar wall of sound about corrosive jealousy.

Transcending them all was “Some Fantastic Place,” the name of the record and arguably the song at the top of their Alps. It pays tribute to Glenn’s ex-girlfriend, the one there at Squeeze’s inception, as she lay dying of leukemia while describing the fragrant afterlife where she expected to be headed. The chords reverberate like “My Sweet Lord,” the exceptional solo one that Glenn had written long ago, as if being saved angelically for this moment, all culminating in a church-like hymnal that parts the clouds of mortality. When my mother died in 2008, I cried myself into spiritual peace listening to it.

She showed me how to raise a smile

Out of a bed of gloom

And in her garden sanctuary

A life began to bloom

***

It’s 2012 at the Greek Theater, and Squeeze has reformed after close to eight years in which Glenn and Chris were no longer on speaking terms like a divorcing couple at wit’s end. An energetic audience swayed and lip-synched to their classics and clapped for muscular, new tunes, including the stunningly good, strings-and-voices-only “Tommy.” When the curtain dropped to make way for the headliner, The B-52s, I seethed. The band that gave us “Rock Lobster” would be blessed to have written any of Squeeze’s lessor-known treasures — “The Truth” or “Elephant Ride,” “Slightly Drunk or ”Play On.” How, I grumbled, could Donovan and the Beastie Boys be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame yet not them?

No Squeeze. No justice.

Two years later, I milled outside The Mint, a small club in LA’s Little Ethiopia district, waiting for Glenn’s solo show. Like the narrator in “Some

Fantastic Place,” I was just emerging from my own suffering after a few dark years; life, as the group once sang, had left “my ends untied,” mine frayed with self-pity. When Glenn climbed out of his tour bus, I zipped up to clasp my hero’s palm. After a crisp acoustic set, I re-approached him for an autograph, nervous as a schoolgirl. I babbled I wanted to “steal Labelled with Love” for a short story, and the man who brought me so much happiness flashed angry eyes at me. I tried digging my way out by saying I wished it’d inspired a play, not realizing it had — in 1981. Glenn smiled, chuckling like an older sibling who saw what this moment meant.

At that point, I was upside down again on my old college ceiling, delirious, $500 forgotten.

Copyright Chip Jacobs. This essay is an expanded version that first appeared in Go Further” More Literary Appreciations of Power Power (The Mixtape Series): Rare Bird Books, 2021

The post My Fantastic Place – An Essay appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

July 23, 2021

My Fantastic Place

Chris Difford, Glenn Tilbrook: your music is my joy machine. Now cough up $500.

Let me explain this cheeky debt. On college party nights my junior year, friends would cram into my boxy, stucco apartment for our peculiar brand of artistic appreciation. Once properly red-eyed from any intoxicants at hand, we’d pick our favorite song, assume a handstand, and then allow pals to hoist us up to the ceiling to “moonwalk” upside-down. Dirty heels were imprinted to the quality rock—the Police, U-2, Cheap Trick—being blared from my Sony stereo. I, however, only inverted myself for you.

Squeeze was the sound I’d been waiting for from the black hole left by John Lennon’s murder and the shallow onslaught of hair-metal. When “In Quintessence” hit that record needle, I went up. Speedy guitar paired with mordant lyrics, about a blowhard adolescent with a pretend girlfriend ignited something in me.

He smokes himself into double vision

Leaves his mind on indecision

Thinks he’s invented imagination

Says that god is some relation

You know who didn’t have any imagination? My tightwad landlord, who at semester’s end eyeballed white ceiling tiles mucked like a mosh pit and declared that I wouldn’t be getting back my security deposit. So, thank you for that.

And bless you for everything else.

For forty-odd years, Squeeze has remained one those mystifying talents whose exceptional catalogue many Americans pop connoisseurs somehow overlooked. Was it because, like The Kinks before them, their feisty independence, their hunger to experiment in the sonic laboratory, their refusal to prostrate themselves to label A&R men made them slippery to pigeonhole? Or, perhaps they were just the right band at the wrong time.

Think about them as a National Geographic special might. Squeeze’s dominant characteristic would be Chris and Glenn singing in octave-apart voices that are somehow familiar and always infectious. Its natural habitat: the pebbly streets and sandy roads of England from which they mined “kitchen-sink dramas” that make you laugh, weep, or simply marvel how they pulled it off. Its growl: Telecaster-fueled arrangements that know when to showcase six-string chops and when to recede. Zoological superpower? Easy. The ability to produce a lightness of being in those who encircle it for pleasure.

I was in the crowd at an Orange County amphitheater to see them after graduation, knowing that their precocious success had thrust them so close to the sun that they’d had to reconstitute after dissolving. I cared little of melted wings, hearing, on one stage, music pulsing with New Wave synthesizers and nods to Elvis, rockabilly-beats and exotic guitar hooks that’d have Jimmy Page a smidge green. Squeeze’s, oft-sardonic lyrics about romance were just as profound as its styles was versatile, too. When they crooned “if I didn’t love I’d hate you,” I grinned, because that’s how I felt about the mercurial, brunette girlfriend next to me.

Listening that night, after seeing so many performers who filled set lists with libidinous and macho themes that disclosed little about the human condition, was a reminder of the brawn of pithy, tactile descriptions. In the elegiac “Vanity Fair,” there’s the dropout who “paints her nails on the bathroom scales.” In the giddy “Piccadilly,” you smell the yellow curry en route to fireplace nooky. In fan favorite “Up the Junction,” you wince for the man who lost everything after “the devil came and took (him) from bar to street to bookie.” In “Revue,” you giggle as the boys skewer a nose-picking, D-list TV host in his “dickie bow ties.”

***

The best pop songwriters you probably only recall from their radio hits or MTV videos were spawned by Chris’ brazen lie. With fifty pence he swiped from his mother’s purse, he posted an ad in a London shop window. Wanted: guitarist “into” the Beatles, Small Faces, Glenn Miller, and others “for (a) band with record deal and touring.” When a younger, shoeless teen in pink trousers turned up about the solicitation, he found that there was neither an established group nor sealed contract. But why quibble when you’re a match introduced to kindling?

Chris, nineteen, was jet-black haired and shy behind his cockiness, a once chubby kid with dyslexia, imaginary friends, a knack for poetry, and a gypsy’s prediction he’d discover happiness through music. After reading a Pete Townsend interview about the globetrotting rockstar life, he decided the gypsy was right. Glenn, with his long nose and slight lisp, was a more extroverted persona and the organic musician between them. Like Chris, he was also a minor rebel (though never a petty criminal). He’d been booted out of school for refusing to shear his hippy-long blond locks. Chris first noticed him sitting in a flower bed playing guitar like a “beardless Jesus.”

The working-class boys united by musical sensibilities and older brothers with health issues penned a hundred and thirty-seven songs in a flash flood of creativity in 1973 and 1974. Frequently, they wrote in all-nighters pungent with candles, weed, and ambition. As the pop-rock world slobbered over Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and Band on the Run, the fresh-faced lads were chiseling their future. A future where they’d sell out Madison Square Gardens, earn a Grammy nomination, and appear on “Saturday Night Live” and “Late Night with David Letterman.” A tomorrow where they’d become an English heritage act, the subject of a BBC documentary, and count Elton John, Paul McCartney, and Dave Edmund as enthusiasts.

Two became one in their songwriting ritual. Chris would scribble lyrics on notepaper, sometimes without lifting pen from pad, and leave them for Glenn. He’d vanish for days or weeks, and then, like a hermit Svengali, slip his much fussed-over arrangements on a cassette under the door for his partner’s delighted ears. Miles Copeland, their first manager, realized they could be huge.

Initially, they performed originals and covers, playing for beer money. They saw contemporaries in Dire Straits and regarded the Sex Pistols as annoying. Rounding out their lineup was now the effervescent Jools Holland on piano and keyboard, the resourceful Gilson Lavis on drums, and the first of several bass players. John Cale, formerly of the Velvet Underground, produced their maiden album by pressuring them to lean into punk rock. While they untucked shirts and affixed clothespins for his benefit, it was an unnatural fit for pop rock troubadours who tilted New Wave with a melodious ethos. Shazam! In “Take Me I’m Yours,” a marching, synchro-beat propels a traveler journeying across the desert toward belly dancers on a tired camel. Deejays and younger audiences hearing their original sound thirsted for more.

Their first US tour wasn’t exactly screaming girls and popping flashbulbs, just the same. At their debut gig, they jammed before an audience of a man and a dog. By the second set, the dog was gone. Oh, well: they traveled in a van, gelling and growing, with Lavis doing his wild-man Keith Moon impression. Their second album, Cool for Cats, reflected musical growth hormone. In “Goodbye Girl,” the repeating keyboard mimics the quixotic heart of a man who awakens from a one-night stand, “on the lino,” with a woman who stole him blind. While Glenn was the Squeeze’s front man on vocals and guitar, Chris, who played rhythm, sang the title song in a gravelly, cockney rasp. Seamlessly, heightened with narrative storytelling that belied his youth, he transitions from cowboys and Indians to his own life as a local celebrity who fraternizes with villains and groupies, the later of whom gave him “a nasty little rash.”

Argybargy, their follow-up, better defined Squeeze in the music-verse as more eclectic than The Cure, less abstract than Depeche Mode, and, arguably, as reliably toe-tapping as Jeff Lynne’s ELO. There were rockers like “Pulling Mussels (From a Shell), which explodes out of the chute, and “Another Nail in My Heart” with its footfalls riff and silky, almost whimsical lead. Deeper in was “Vicky Verky,” a bubble-gum-fast ditty exploring forbidden love and abortion, and the boogie-woogie of “Funny How It Goes” about hitting on “champagne women.” Heard live, you’d swear that not only was the entire band playing on speed but the song themselves had dipped into the rainbow diet pills.

Then … drumroll to legend status. The record that Rolling Stone touted as one of the best albums of the decade, the record I wore into vinyl exhaustion, was 1981’s East Side Story. Here, Squeeze smashed its mics through the walls frowning on power-pop genre-hopping. The album gushed with blustery youth (“In Quintessence”) and hummable, blue-eyed seduction (“Tempted”); it evoked female depression (Woman’s World”) about a housewife so unfulfilled by her “shiny new appliances” that she can barely stagger home from the bar. The sleeper is the tear-jerking, country ballad “Labelled with Love,” told with the tenderness of a novel in which the protagonist reflects back on a halting life of loss. In this case, it’s an arthritic widow returning to her native England from the Texas prairie amid the ruins of alcoholism.

She unscrews the top off from her new whiskey bottle

Shuffles about in her candle lit hovel

Like some kind of witch with blue fingers and mittens

She smells like the cat and the neighbors she sickens

Produced by Elvis Costello, East Side Story was a revelation, a comet streaking across the Top-Forty sky. But then something dreadful happened: invocation of the much-coveted but always hazardous B-word. Rolling Stone dubbed Difford and Tilbrook “the next Lennon and McCartney,” with other critics piggy-backing onto the comparison. As soon became evident, it’d be millstone by the ultimate flattery. Mortals assured they were gods.

On cue, egos bloated, ears were whispered into, and coke vials overflowed their rims. As Chris later admitted, band members started rowing in different directions after this heady correlation. Yes, he sketched urban scenes and quirky people with uncommonly literate observations. But where the Beatles blossomed from love-song-focused mop-tops to path-breakers exploring everything — taxes, loneliness and psychedelic hallucinations, serial killers and universal love — Chris remained in his own detached headspace. Rather than including “Chairman Mao” or a “Billy Shears” character, he focused on self-demons wrestling with survival, addiction, infidelity, and, much later, in “Please Be Upstanding,” erectile dysfunction. Sure, Glenn’s voice resembled Paul’s in pitch and ability to modulate, but his rangy musicianship was as much influenced by his idols Jerry Garcia and Jimi Hendrix as George Harrison’s.

The world craved the next Fab Four, however it got it. Whatever the collateral damage.

Squeeze, dizzied by the parallels to world-changers, fried by the tour-record-tour-record drudgery, sallied forth, brave as ever. But where Magical Mystery Tour sounded like the sequel to Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band, Squeeze’s next albums were never as wall-to-wall bravura as East Side Story. Which isn’t to suggest that they were sputtering on fumes. “King George’s Street” is a marital split, expressed in power chords and emotion, through the eyes of children. In the brassy “Hourglass,” they bagged their biggest US hit. “Melody Hotel,” a twangy takeout about a family man who abused prostitutes, would’ve been an ordinary group’s encore sensation.

Before splitting up again as fissures widened between ever-creative, if stubborn Glenn and fragile Chris, who’d previously bailed on a US tour, self-medicating inner-pain with vodka, powder, and isolation, Squeeze’s tenth album sparkled. It just gleamed in 1993 as grunge-rock overtook the airwaves. In the blazing “Third Rail,” the antihero gives the bottle choking him its walking papers. “It’s Over” is an acoustic-guitar wall of sound about corrosive jealousy.

Transcending them all was “Some Fantastic Place,” the name of the record and arguably the song at the top of their Alps. It pays tribute to Glenn’s ex-girlfriend, the one there at Squeeze’s inception, as she lay dying of leukemia while describing the fragrant afterlife where she expected to be headed. The chords reverberate like “My Sweet Lord,” the exceptional solo one that Glenn had written long ago, as if being saved angelically for this moment, all culminating in a church-like hymnal that parts the clouds of mortality. When my mother died in 2008, I cried myself into spiritual peace listening to it.

She showed me how to raise a smile

Out of a bed of gloom

And in her garden sanctuary

A life began to bloom

***

It’s 2012 at the Greek Theater, and Squeeze has reformed after close to eight years in which Glenn and Chris were no longer on speaking terms like a divorcing couple at wit’s end. An energetic audience swayed and lip-synched to their classics and clapped for muscular, new tunes, including the stunningly good, strings-and-voices-only “Tommy.” When the curtain dropped to make way for the headliner, The B-52s, I seethed. The band that gave us “Rock Lobster” would be blessed to have written any of Squeeze’s lessor-known treasures— “The Truth” or “Elephant Ride,” “Slightly Drunk or ”Play On.” How, I grumbled, could Donovan and the Beastie Boys be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame yet not them?

No Squeeze. No justice.

Two years later, I milled outside The Mint, a small club in LA’s Little Ethiopia district, waiting for Glenn’s solo show. Like the narrator in “Some Fantastic Place,” I was just emerging from my own suffering after a few tragedy-stricken years. When he climbed out of his tour bus, I zipped up to clasp my hero’s palm. After a crisp set, I re-approached him for an autograph, nervous as a schoolgirl. I babbled I wanted to “steal Labelled with Love” for a short story, and the man who brought me so much happiness flashed angry eyes at me. I tried digging out to say I wished it inspired a play, not realizing it had—in 1981. Glenn smiled, chuckling like an older sibling who saw what this moment meant.

At that point, I was upside down again on my old college ceiling, delirious, $500 forgotten.

Copyright Chip Jacobs. This essay is an expanded version that first appeared in Go Further” More Literary Appreciations of Power Power (The Mixtape Series): Rare Bird Books, 2021

The post My Fantastic Place appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

June 16, 2021

The Boom that Blew the Petals off the Rose City

Square-jawed and persuasive, developer E.C. Webster, it was said, could’ve sold plots on Mars for a profit. Luckily there was Pasadena of the late-1880s, where Webster’s knack for acquiring properties at “shoestring prices” before reselling them for nifty gains made him a legend.

The dealmaker behind the Hotel Green, the Grand Opera House, and Raymond Avenue’s opening typified a boomtown spirit champing to wring fortunes from the land. And what a spirit it was. Between 1886-1887, a foothill plain known for citrus groves, sheep pastures, and a single saloon transformed into, arguably, one of the hottest real estate markets in America.

Pasadena’s founding fathers in the “Indiana Colony,” who a decade earlier had espoused equitable property division among its members, surely cringed at the frenzied activity. If you had cash, you were cajoled to invest. If you owned a tract, you were wooed (or badgered) to subdivide.

Take the case of O.H. Conger, who accepted a syndicate’s $15,000 offer (about $406,000 today) for his twenty-acre orchard south of Colorado Street in this period. He netted a $5,000 windfall. Craving more, the buyers held an auction they marketed with free train rides, complimentary grub, and a brass band. Though some deemed the event indecorous, seventy-seven of the eighty-seven lots divvied up from Conger’s property sold for a collective $22,000.

The county recorder’s office illustrated this was no fluke. During the “great” land rush, Los Angeles, then twelve-times larger in population, filed 549 subdivision maps. The future home of the Rose Parade submitted seven times more.

Speculators, or “boomers” as were tabbed, seemingly crept everywhere in a town still lacking a charter, reliable water system, or decent bridge across the Arroyo Seco. They and the fifty-three local real estate agencies brokered transactions in Victorian-age offices and on plain sidewalks. They shadowed rivals doing site tours to swoop in once they left. They pounded on homeowners’ doors at midnight dangling can’t-miss sales-contracts. They twisted fancy moustaches, soliciting clients with fountain pens and promises.

Conservative financiers fretted the real estate bubble would burst, but it wasn’t a universal opinion. As the Valley Union wrote with a racial tweak: “Put your money to soak in real estate rather than in a Chinese washhouse.”

Many heeded that siren of temptation. A landowner pestered to sell five acres he purchased in 1881 for $2,000 eventually acquiesced to chop up his parcel. He turned a sixty-fold profit. In another case, a lot at Marengo Avenue and Colorado Street where the First Methodist Church once stood became—what else—a residential subdivision.

One evening, a druggist was compounding medication with a mortar when speculator Johnny Mills rushed into his pharmacy. In his hand was a map displaying a plot that he urged his would-be client to snap up before other bidders the next day. The preoccupied druggist refused to glance at the document, so Mills gestured to a jingling streetcar outside waiting for him to say final chance.

Five minutes later they had an agreement. Shortly after that, Mills represented the pharmacist reselling the plot in a classic flip you’d see today on HGTV.

All told, twelve millions dollars ($324 million now) in deals were transacted in 1887. Weed-strewn lots, forlorn houses, vine-covered bungalows; crumbling shacks—all what mattered was their future worth! Why not, when a $300 parcel on Fair Oaks two years later fetched $10,000?

Years before Old Money Pasadena crystallized on Orange Grove’s Millionaire Row, the nouveau riche lived high on the proverbial hog. Men booked hotels for boozy stag parties and poker games. Others flashed diamonds, rode in fine buggies, and ditched nickel cigars for gold-banded ones.

Amid the feverish wheeling and dealing, bigger investors jumped in ways that expanded Pasadena’s reach. An electric light and power company hung out a shingle. Developments on new streets—Los Robles, El Molino, and Lake avenues— pushed activity eastward. Colorado Street underwent a partial street paving, and welcomed the new Arcade building and fresh shops. To keep pace will all the building, a dirt-streaked tent city to shelter workers popped up in what’s now Central Park.

Then, as quickly as it started, the law of economics prevailed once the market bottomed out. Sellers now dwarfed buyers. Commercial lending slowed to a trickle. Auctions proved duds. Before long, some of those high-flying speculators vanished (probably with investors’ money). One hustler who’d made six figures in real estate resorted to selling peanuts on trains for his keep. Another drove a mule pulling a streetcar.

The way amateur historian J.W. Wood saw it, “The paper fortunes, and some more substantial, had collapsed with amazing celerity, and the dazed and sickened boomers’ dream was over!”

Pasadena’s future might’ve tanked, too, if the banks, whose net assets had plunged by two-thirds, didn’t grant loan-repayment extensions, or aid customers staving off bankruptcy. The population nosedived anyway, as people left behind their failures, only resurging in the next century.

As for E.C. Webster, Wood reported he abandoned his “castles in the air” for a docile life in Missouri.

Unless indicated, monetary figures were not adjusted for inflation.

The post The Boom that Blew the Petals off the Rose City appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

1979 L.A. True-Crime In Song

It was the faces that slayed you that year, when the only reason for a belly-laugh was a Robin Williams standup act.

The expressions remain amber in memory: the knotted foreheads of Pennsylvanians near the meltdown at the Three-Mile Island nuclear-power plant; Jimmy Carter’s clenched grin realizing circumstance would relegate him to a one-termer. How a January than began hopefully with Terry Bradshaw’s aw-shucks glee after winning a Super Bowl in Miami metastasized by November into rage and disbelief at the righteous scowl of Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, who proclaimed “Death to America” as his followers took U.S. embassy workers hostage in Tehran.

For me, an ever-curious seventeen-year-old in the foothills of Pasadena, California, those flickering images, as well as other dismaying ones — the victims of crisscrossing serial killers, dying steel towns, Soviet tanks rolling into Afghanistan — seeded doubts about pretty much everything concerning the future. It was a kind of “Deer Hunter” state of mind.

So, blessed be for those unleashed Les Pauls, for thumping bass riffs, for singers going where the suited adults wouldn’t. The chrome housing of my pride-and-joy Sony stereo rarely grew cold, not as I gorged on a feast of eclectic, envelope-stretching music that painted my world the vivid colors seemingly bled out of the real one. Classic albums, melodic punk, dangerous New Wave: if you needed pretext for an album party, there was always cellophane to unwrap.

Blue-blood acts I adored — Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd — were proving they weren’t longhaired dinosaurs ducking comets named Deborah Harry, Joe Strummer, Robin Zander or David Byrne. And just as Blue Oyster Cult sang about how nature continually revealed the foolishness of man, 1979 also sped the destruction of the glittery dance ball born from Barry Gibb falsettos, at least as evinced by a crowded, “anti-disco” night in Chicago I wish I could’ve attended.

Why am I effusing about music created when Beyonce wasn’t even born, churned out by musicians with the faint ring of a dive-bar Throwback Thursday trivia contest?

In March of that year, on a rainy evening several freeways away from my bedroom poster of Jimmy Page in his white, dragon pants, a trio of wannabe assassins crouched on the deck of a suburban house in the San Fernando Valley, “America’s Suburb:” The killing in their sights would serve multiple purposes: as trance-inducing revenge for its mastermind, and as the inauguration of his murder-for-profit ring targeting real estate executives who squirreled hefty sums of cash at home.

Though I wouldn’t piece together this entire, bizarre story until 40-plusyears later, well after I junked my corduroys and mix-tape cassettes, it got me wondering. How would the saga of an only-in-LA business partnership — devolving as it did into treachery, gore, and criminal absurdity — sound if it was told by radio-blared songs rather than the pages of the true-crime book I wrote?

My parameter: do it with through ten works released in ’79, narrowing them to either top-sellers listed by Billboard magazine or ones praised by Rolling Stone and others. My reasoning: music is a sonic reverberation of its environment, often depicting the era’s vibe better us than later moored to a keyboard.

***

Once upon a time, there was a young space planner (a.k.a. interior architect) who was brilliant and nerdy. He also wrestled with the labels the city slapped on him, sometimes unsure which way was up. Supertramp’s “The Logical Song” must’ve been his jam.

To compensate for his inexperience, the space planner hired a suave, older associate to be the public face of their upstart firm, Space Matters. This man, from a wealthy West L.A. family that’d yoked high expectations on him, was equally ambitious but also more risk-taking. He sweet-talked his partner into adding hard-hat construction services to their otherwise white-collar enterprise.

“Stagflation” economy” and all, Space Matters killed it at first, inking deals from grand dame Wilshire Boulevard to the futuristic westside. Anyone been to Tom Petty’s “Century City?” They sold to insurance companies and stuffy banks, pop-psychology groups advocating nudity, weed, and primal screaming, as well as a sixties’ counterculture figure turned leasing tycoon. For strange bedfellow colleagues working out of an old mansion near L.A.’s posh “Miracle Mile,” they rolled like they were, in Police vernacular, “Walking on the Moon.”

Voyages, however, are propelled by trust and expertise, not deception camouflaged by toothy smiles. The very partner the young space planner recruited had actually cheated him out of tens of thousands of dollars, jeopardizing everything they’d built. At an ambush meeting at the glitzy Polo Lounge, the blow-dried embezzler was booted out of the promising firm. Let Joe Jackson explain how flimflams are devised. “I’m The Man.”

If this were the old Dick Clark game show, “The $20,000 Pyramid,” the grand-prize question would be why such a talented, charismatic person needed to resort to such knife-in-the-back trickery? The regrettable answer: uncontainable demons, self-shame, and, beneath the surface, paranoia that his wife, a spunky, ravishing woman much his junior, needed to be indulged, lest he lose her. She was, more or less, his “My Sharona,” as presented by The Knack.

The problem with cheaters is that they often cheat multiple suckers, with some less willing than others to answer with a lawsuit or eternal disgust. A monster, who hide behind the legitimacy of his nine-to-five, Joe Sixpack persona, put a contract out on the trickster as proof. When the first assassin he hired to take care of the matter developed cold feet and fled up north, he found himself on the execution list, becoming a “Renegade,” albeit not how Styx imagined.

Even with blinking lights he was being hunted, the older space planner — a man with two daughters, an estranged spouse still open to reconciliation, and many others who loved him — remained in LA when he should’ve booked a flight on the Concord to a remote European village. To squish down his inner torment, he hooked up that stormy night with a former secretary, then rolled himself a doobie, feeling “Comfortably Numb.” He just could’ve used a wall more fortified than Pink Floyd’s.

The mastermind pounced on his target’s lethargy, driving his El Camino across at least four freeways with his bottom-scraping, gaffe-prone toadies. The intent was bloodier than AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell.” Job done, dozens of Angelenos connected to a bullet-pierced window were petrified of opening their curtains — or seeing that shark-like Chevy round their block. They knew, like Elvis Costello knew, that “Accidents Will Happen.” They just didn’t understand who picked the victims.

Nobody had more reasons to keep looking over his shoulder than our nerdy space planner. For months, he “lived” in disguise, under occasional protection of an-ex Israeli mercenary, surviving a botched showdown at the creepy La Brea Tar Pits. It’d take him decades before he could live as blithely as the louche, good timer in Squeeze’s “Cool for Cats.”

And only then with a raging mistrust of the true L.A. behind its sunny mask.

To hear the Spotify playlist from this essay, click here!

The post 1979 L.A. True-Crime In Song appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

June 14, 2021

The Accidental True Crime Writer

WHEN MY CITY EDITOR yelled out that she needed someone to help cover a shooting at the County General Hospital in East Los Angeles, I sunk low behind my computer, trying to be invisible. As a young metro reporter focusing on transportation back in 1993, I had barely typed a word about violent crime.

Forty minutes later, I lingered near one of the hospital’s side entrances, unable to spot any fellow journalists milling around. So, I popped open the door, figuring they might be inside. That’s when a tubby police officer whipped around the corner, telling me in an angry whisper that the gunman who’d already shot three doctors — one with a .38-caliber slug to the head — was holding two people hostage just around the bend. “Get down and go!” he said, his hand gripping a revolver.

I left, lucky only to have been chastised, and discovered the media scrum in an adjacent parking lot. It was now your basic hurry-up-and-wait while authorities tried to end the standoff with the gunman, a disgruntled patient who lived on Skid Row. They hauled him off in a squad car after several hours, and as I angled for a view of his face, an overly aggressive TV cameraman whacked me in the back of the head with his lens. But I still noticed the suspect resembled Richard Ramirez, the “Night Stalker” serial killer who had terrorized Los Angeles the previous decade.

By nightfall, with our story for the San Gabriel Valley Tribune in editing, I needed to decompress. I ripped off my nicotine patch and bought the last pack of cigarettes I’d ever smoke.

The O. J. Simpson murders would be the next crime story I’d write about, if tangentially, for the Los Angeles Times and its rival, the Los Angeles Daily News. Full-time crime reporters, as I learned, were the characters in the newsroom, often cynical, swashbuckling, and as brash as the cops with whom they interacted. I didn’t run in that herd.

It wasn’t until one day in 1998, strolling along Hollywood Boulevard, that I got stopped on the sidewalk by a guy named Jerry Schneiderman who had been both a source for stories and a bit of a fabulist.

“Did you know,” he said, “that I once had a double murderer chasing me?”

He claimed the ordeal ruined the “old” him, gutting his first marriage and leaving him forever mistrustful of strangers.

Yeah, right, I said, figuring he was either pulling my chain, as he was apt to do, or exaggerating something unverifiable.

Never was I more wrong.

Schneiderman had been a nerdy 27-year-old space-planning prodigy when his partner, a suave, charismatic fellow 12 years his senior, persuaded him into something of a real estate get-rich-quick scheme: adding construction services to their otherwise white-collar business sketching interior blueprints for Los Angeles companies big and small. In need of an experienced foreman — and a California contractor’s license — they hired a quiet, windburned applicant, sight unseen. What Schneiderman didn’t know was that both his colleagues bore secrets, one more diabolical than the other. From the ashes of financial misconduct and palace intrigue soon emerged a sequence of events out of an Elmore Leonard novel.

Then again, life in 1979 Los Angeles made for plenty of deadbolted doors and just as much paranoia. Murder rates were spiking. “White flight” was growing, as were gated communities and racial tensions between people of color and the increasingly militarized LAPD. Worse, overlapping serial killers (like “The Hillside Strangler” and “The Freeway Killer”) seemed to prowl at their leisure.

Beyond the criminality, Southern California exuded this seething aura, just like the rest of a demoralized post-Vietnam, post-Watergate United States, except amid palm trees and famous boulevards. The anchor’s rant in Paddy Chayefsky’s brilliant Network, where he encouraged viewers to scream that they were “mad as hell,” felt less Hollywood drama than modern documentary. There was a noir quality to our existence that rendered even our beloved La Brea Tar Pits a shadowy expanse you didn’t want to hang around at night. A 17-year-old at the time, what I remember now are the gloomy skies and sullen adults.

Years later, I realized that Schneiderman only had a keyhole-wide understanding of the darkness that had swirled around him. For instance, he had little understanding that his partner’s execution with a powerful World War II–era rifle represented the opening salvo in a boutique murder-for-profit corporation. The ringleader of it was Howard Garrett, their vulture-faced foreman who’d decided to toss caution to the wind by cashing in on other people’s demises. In a tense meeting where Garrett blackmailed Schneiderman, threatening him and his family with their own murder contracts, Garrett warned Schneiderman that he had killed before “and gotten away with it.” He wasn’t lying.

The web of would-be assassins that ensnared Schneiderman included a bantam-sized gunman with a deadeye aim, a transgender thief, and a bisexual white supremacist crook with a grain of conscience.

But I never could’ve unearthed a drop of this 20-year-old saga without my journalism background. As such, I spent hours in the Hall of Records’s dungeon-esque basement in downtown Los Angeles, examining court filings, even though many were missing or stolen. I interviewed dozens of people swept up in Garrett’s months-long reign of terror, among them former LAPD homicide detectives who, like Schneiderman, couldn’t forget Garrett. Eventually, I connected with the lead prosecutor, who offered public documents that confirmed the outlines of this weirder-than-fiction tale.

One salacious document showed that between the time when Schneiderman’s business partner was murdered and Garrett was dramatically arrested he worked on a freelance construction job at the offices of the California Association of Realtors, a trade group promoting integrity in the real estate business.

All of this digging kept me at a comfortable distance from the actual villains involved. I still craved to learn more, and with Garrett long dead, there was only one person who knew the truth about him: the triggerman who’d fired the fateful bullet into the head of Schneiderman’s feather-haired partner, Richard Kasparov.

Johnny Williams was many things: a bushy-haired man who had already admitted to killing multiple people before this, an industrious criminal alchemist, and the victim of a traumatic brain injury from tumbling out of a moving car. That pivotal event had demented him from a kid with a soaring IQ into a sociopath.

To hear him out, I typed up a letter requesting an interview, and then, probably a dozen times, stuck it in my mailbox only to retract it moments later. Williams had testified under oath, to a stupefied courtroom, that killing to him was no big deal. Years later, the parole board at Corcoran State Prison in Central California repeatedly denied his release, deeming him an ongoing threat to society.

What if my nosy questions about what landed him behind bars incensed him and he was subsequently freed? Even the internet of the early aughts made it simple to locate someone’s address. Would he pop up outside my window with a big gun, just as he had with Schneiderman’s partner, for one last slaughter? What about my family? Were Williams’s sinister memories worth it?

That one-page letter collected dust in my file cabinet for two years as I hemmed and hawed, weighing the risk, when I heard that Williams died behind bars.

Then I wrote The Darkest Glare, a nonfiction account that tried to stitch all the craziness together into a single book. I hope I did it justice without Williams.

I was confident I could handle not only the Kafkaesque twists of Schneiderman’s ordeal but also the prologue of it — the PTSD, the legal and emotional dominoes that cascaded afterward, the questions about hidden identities behind the smiles of Los Angeles contractors. And that’s all because a distracted city editor shooed me out the door to cover that hospital shooting. The best story is the one you never set out to write.

The post The Accidental True Crime Writer appeared first on Chip Jacobs .

Killing Machines: How Car Culture in 1970s Los Angeles Fueled a Terrifying String of Murders

During the late-1960s, with Los Angeles’ skies still blotted by poisonous smog, an angry mother fastened a sign in her station wagon that you never would’ve imagined in the planet’s car capital. “This GM,” her placard read, “is a killing machine.” Intended as an activist war cry, her words by the end of the next decade carried a more diabolical meaning.

Predators were no longer only skulking neighborhood back alleys or through unlatched windows to snatch up their quarry. They were adopting their own vehicles as murder accomplices, exploiting Southern California’s go-anywhere roadways to create distance between themselves and the corpses they left behind. For these dark-eyed sadists, every highway off-ramp presented temptations, every on-ramp a getaway to blend in with thousands of other taillights on concrete stretching into the horizon.

Consider William Bonin, a mustachioed truck driver and ex-Vietnam War helicopter pilot who in 1979 and 1980 stalked young men to abduct, torture, and slaughter in his van. The media gave him an accurate, if sensationalized moniker. The “Freeway Killer,” along with his collaborators, would butcher twenty-one people before being apprehended. Giving himself space to operate with impunity, Bonin once deposited a body just off the Golden State Freeway forty miles from his Downey home southeast of Los Angeles.

Rivaling him in this high watermark era of serial-killers was Angelo Buono Jr., the so-called “Hillside Strangler,” who, together with his cousin snuffed out victims in Buono’s auto upholstery shop in Glendale northeast of LA; sometimes they’d position their victims in lurid poses off local roads to ridicule police. In 1978, a female college student they kidnapped was later discovered in the trunk of her Datsun, which had been shoved over a cliff off mountainous Angeles Crest Highway directly behind my high school.

That same year, while NBC broadcast its series “CHiPs” about fictional California Highway Patrolmen gliding along flyover interchanges and breezy straightaways, two real-life henchmen set out in a green Plymouth to terminate someone hundreds of miles south. Their assassination target was Paul Morantz, a feather-haired lawyer crusading against the group that radicalized them: Synanon, a former drug-and-alcohol detox turned xenophobic cult. In otherwise picture-postcard Pacific Palisades above Santa Monica, the pair stuffed a nearly five-foot-long rattlesnake into the attorney’s mail slot. Despite being bitten on the wrist in a bizarre, attempted homicide by reptile, Morantz survived.

The conclusion, even so, was indisputable: the same steel-and-chrome rides synonymous with West Coast suburbia and personal liberty—the same whitewall models churning never-ending windfalls for Detroit’s carmakers, had betrayed us. Air pollution that experts vowed would be long gone continued to dirty the atmosphere like an ashtray, triggering more deaths from lung diseases, heart ailments and such than gang violence, overseas wars and car accidents combined. It barely ended there. In this era of simmering disillusionment about the post-Watergate American way of life, motorists threw punches waiting in blocks-long lines at gas stations following a Middle East oil embargo. Out on LA’s Westside, drivers incensed by experimental “Diamond Lanes,” which were intended to reward carpoolers in ever-gnarled traffic, hung then-Gov. Jerry Brown’s transportation chief in effigy. Before long, scenes of shattered windows from drive-by shootings in the inner-city would be prosaic on the 5 p.m. news.

Aside from my own teenage run-ins with hotheads practicing road rage before the term was coined, I had no idea that the vicious prowled hunting grounds from the comfort of their bucket seats. It wasn’t until—for a book project—I immersed myself in the drama of Howard Garrett and his rainy-night execution of an upstart interior architect that I realized that 1979 was our season of odometer-fueled discontent.

Garrett, a middle-aged blue collar contractor with a vulturous aura, was defrauded by said architect in a soured partnership. So, he put his steel-blue El Camino front and center in a months-long reign of terror. He’d previously transported inside his camper shell—across crisscrossing freeways—a junkie he had pummeled to death with a rifle butt. By abandoning his burning corpse in scrubland in another county, Garrett knew he’d throw detectives off his scent. He did, repeating this same alibi-by-separation philosophy when he founded a boutique, murder-for-hire corporation focused on real estate executives. To entice “employees” to do his bidding (and also scapegoat, if necessary), he offered them use of his prized Chevy, a half car, half truck with the ground-hugging profile of a bull shark. Anyone in his criminal retinue who borrowed it without permission risked their necks, as if Garrett’s creepiest secrets were welded inside the door panels.

On the evening he decided to accompany his minions to kill his target after they’d bungled the job on multiple occasions, it was the El Camino they drove, traversing at least three freeways—the 10, the 210, and the 101—to reach their destination on a leafy block in the San Fernando Valley. Job completed, they motored north, towards the Magic Mountain amusement park, where the triggerman chucked most of the disassembled murder weapon out the window.

Fittingly, Garrett’s bloody handiwork warranted only a short news brief in the local paper—right below a story about TV-comedian’s Red Foxx’s assault charges. Why? 1979’s record-setting murders, from ritualized killings and professional hits to domestic disputes and gang shootings, made for stiff front-page competition.

Today, the car-reliant predators of the seventies have faded in the limelight, giving way to AR-15-brandishing mass shooters, while the gray-brown airs that had so many coughing is mostly history. In contemporary LA, the real serial killer doesn’t bear a catchy nickname or a police sketch. It’s the climate-warming gases seeping out of almost eight million automobiles here that add to graveyards worldwide by the tens of thousands. “Killing” machines indeed.

This essay is nearly identical to the one that originally ran in CrimeReads.

The post Killing Machines: How Car Culture in 1970s Los Angeles Fueled a Terrifying String of Murders appeared first on Chip Jacobs .