Abdul Rotimi Mohammed's Blog: Enlightment blog, page 4

March 9, 2023

Africa’s Malthusian Trap Part 2: In search of Africa’s demographic transition

Source: Max Roser http://ourworldindata.org/data/popula...

I had ended my last post by stating that I was going to explain Africa’s population explosion and the west’s lack of it. I ended by saying the west (and increasingly, Asia) are the beneficiaries of what is known as the demographic transition.

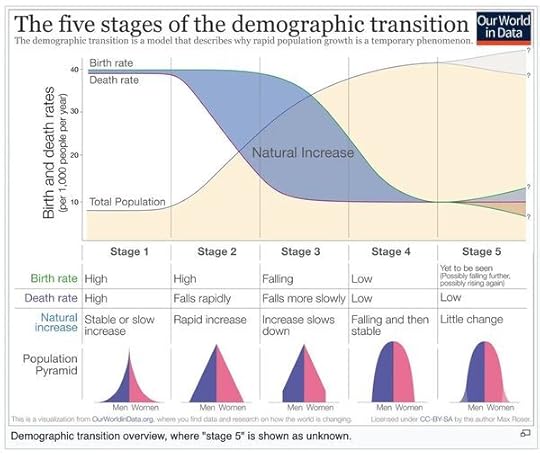

The demographic transition refers to a phenomenon where there is a shift from high birth rates and high death rates in societies with minimal technology, education (especially of women) and economic development, to low birth rates and low death rates in societies with advanced technology, education and economic development, as well as the stages between these two scenarios [1]. As can be seen from the graph above, the transition is divided into 5 stages. Stage 1 is characterized by high birth rates and high death rates. During this stage, the society evolves in accordance with the Malthusian paradigm, with population essentially determined by the food supply. Any fluctuations in food supply tend to translate directly into population fluctuations. In stage 2, the death rates drop quickly due to improvements in food supply and sanitation, which increase life expectancy and reduce disease. This is the stage that characterizes developing nations. The resulting fall in death rates tends to lead to a population explosion. In stage 3, birth rates begin to fall rapidly as a result marked economic progress, an expansion in women's status and education, and access to and use of contraception. In stage 4, both birth rates and death rates are low. At this stage it is possible for birth rates to dip below death rates and thus have a shrinking population as is the case in Japan.

The advanced countries of the West, and of East Asia (Japan being the most prominent here) are at stage 4. Most of Sub-Saharan Africa is at stage 2 but a handful of them namely, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), Lesotho, Namibia, Kenya, Gabon and Ghana have begun to move to stage 3 [2]. Some observers believe that many Sub-Saharan African nations are stuck in stage 2 as a result of stagnant development [3]. It should be of concern to us that countries are vulnerable to becoming failed states in the absence of progressive governments at this stage. No country is yet to experience stage 5. Of course, it is important to remember that that the demographic transition is just a general picture and not a specific description of the path each individual country goes through.

There are competing explanations as to why the demographic transition happens. A leading explanation is that people undergo a change in values as their country industrializes. Some of the value changes include greater emphasis on female education, and delayed marriage age. Also important is that successful industrialization arguably provides the greatest opportunities for people to be gainfully in the formal economy. This crucially gives people access to steady employment and retirement benefits like pension plans. Pension plans reduce the incentive to have large families. Prior to the establishment of the formal economy, adult children were the primary form of insurance for adults in old age [4]. To the extent that we do not industrialize, is the extent to which we keep people dependent on adult children as their pension, and hence, the incentive to have large families remain, with the attendant risks of serious social unrest, stemming from the inadequate resources required for a burgeoning population. This is what drives many of Africa’s poor to have large families. They are not stupid. Their actions are entirely rational. We ‘educated’ Africans need to understand that illiteracy isn’t the same thing as stupidity. You can be illiterate and smart. You can also be educated and stupid. Furthermore, preparing children to be members of the formal economy is expensive and this further reduces the incentive to have large families. Contrast that with raising children to help you work your small plot for your subsistence farming. The cost of raising children in this case is barely more than the cost of feeding.

You shouldn’t think the attitudes of Africa’s poor towards child-bearing is unique to Africans. Europe’s poor behaved exactly the same way 200-300 years ago before the Industrial Revolution, because they were trapped in the exact same socioeconomic conditions that Africa’s poor today, finds itself in. I am highlighting this because I want to make two general points; Values, and hence culture is not static; Some values, hence, some aspects of culture are universal. I would like to elaborate further on these two points.

The above discussion on the democratic transition should make it clear that each stage of socioeconomic development imposes its own values on a given society. So inasmuch that the culture of a people is derived from its values, culture is by nature, meant to be an inherently fluid concept. In simple words, culture is not set in stone but is meant to change as the prevailing realities in the environment demand it. On the second point, as a result of a lack of exposure to history, and to other groups of people and their respective cultures, people of a certain group often think their outlook and values are unique to them and that such outlooks and values have not been held by other people at any point in history, hence they are led to the mistake that there is nothing to be gained from the experience of other people. Some values have shown themselves to be universal in the sense that they have the potential to be held by all people. They just haven’t been held by all people at the same time.

There is a very big danger that awaits countries that don’t make it out of stage 2 (which I previously mentioned is the stage which most of Sub-Saharan Africa is in) known as the demographic trap. The demographic trap refers to a situation where countries in stage 2 remain stuck because they are not creating enough economic development to match their explosive population growth, resulting in increasing poverty, which in a very pernicious way, encourages even more population growth because even more people find themselves trapped outside the formal economy and therefore look to adult children as their pension plans in their old age [5], which of course, increases poverty. It is a vicious cycle. If things get really bad a stage 2 country might find itself experiencing a reversal and find itself headed back to stage 1 [6]. According to Population Action International (PAI), a global think-tank and advocacy group, this reversal has already started in Nigeria [7]. PAI claimed this had happened as far back as 2006. It is needless to say that such a scenario seriously increases the potential for civil conflict. Two globally renowned scholars, have gone on record to claim that the Rwandan genocide was ultimately the result of population pressure. One of them, Edward O. Wilson [8], famous for developing the field of sociobiology and for discovering the first colony of fire ants in the United States as a secondary school student, pointed out in his remarkable book Consilience, that between 1950 and 1994, the population of Rwanda more than tripled from about 2.5 million to 8.5 million; that it had the highest growth rate in the world in 1992 with 8 children per woman. He claims that the overpopulation and the dwindling resources were the inflammable material that were finally lit by the match of ethnic tension between the Hutus and the Tutsis [9].

I had started this post by explaining the demographic transition. I had also mentioned that industrialization has been recognized as being key to bringing this transition about. Sub-Saharan Africa’s relatively feeble attempts at industrialization put much of it at risk of being caught in the demographic trap or worse, the Malthusian trap. The stakes are just too high not for us not to take this issue seriously.

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this post with as many people as possible and please check out my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe on Amazon. Thank you

References:

1. Wikipedia article on the demographic transition https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demogra...

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Ibid

5. Wikipedia article on the demographic trap https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demogra...

6. Ibid

7. Leahy, Elizabeth Nov 2006 ‘Demographic Development: Reversing Course?’ http://www.populationaction.org/resou...

8. Wikipedia article on Edward Wilson https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._O._W...

9. Wilson, Edward. 1998 Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. UK: Abacus

Published on March 09, 2023 22:52

February 27, 2023

Africa's Malthusian Trap

In the year 1798, clergyman, mathematician and the foremost economist of his time (alongside David Ricardo) Thomas Malthus published a book, titled An Essay on the Principle of Population in which he painted a rather gloomy future for mankind. The book was a response to and a critique of the rosy projections of his father whose views was influenced by some of the leading philosophers of his day. Young Malthus felt those rosy projections were not firmly rooted in science and therefore sought to come up with a projection based on solid mathematical reasoning.

In the book, he pointed out that while population grew geometrically, food production only grew arithmetically. Some at this point might need a refresher on geometric and arithmetic progressions. A geometric progression looks like this:

2, 4, 8, 16, 32……

While an arithmetic progression looks like this:

2, 4, 6, 8, 10……..

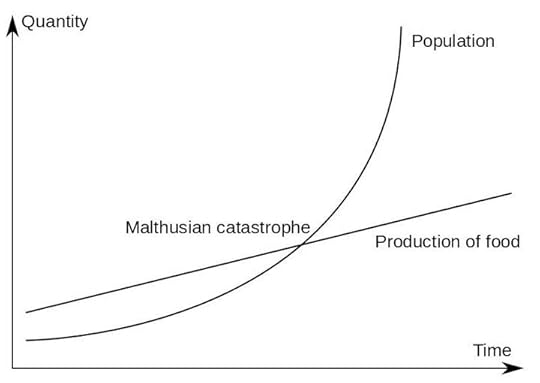

So Malthus’ contention was that population growth would at some point, outstrip increases in food production, as depicted in the graph above, and that undesirable events like war, famine, and pestilence would inevitably occur to restore the balance. Unsurprisingly, such a sweeping premise has stoked and continues to stoke a barrage of criticism since it was made. Yet that the debate still rages on till this day, is itself proof that Malthus’ premise contained within it considerable force. One particularly valid criticism was the one put forward by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the founders of Marxism. Their contention was that scientific and technological progress is as unlimited and at least as rapid as that of population growth [1], and in this they have emphatically been proven right. I feel obliged to say in Malthus’ defense that when he published his book in 1798, the Industrial Revolution had only been going on for merely 40 years. There probably hadn’t been enough time for it to raise productivity levels to have discredited Malthus theories at the time he published his book. On the other hand, Karl Marx was born 1818, A full 20 years after Malthus published his book. As an adult, Marx got to witness first hand, industrialization working its magic, moving full steam ahead. Moreover, demographers and other scientists see Malthus’ theory, as an accurate description of pre-industrial western society [2].

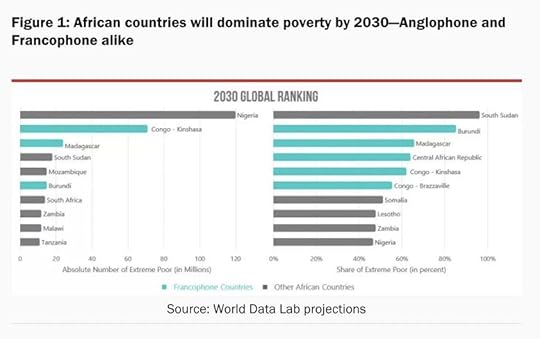

Now the worrisome thing for Africa is that Malthus’ theory is seen as a valid description of contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa as Sub-Saharan economies are largely pre-industrial [3]. Now the improvements in medicine and sanitation since Malthus’ time, and the development of international markets, which make possible the importation of some machinery (which has its own attendant problems) will probably prevent the ghastliest scenarios that Malthus envisioned but Africa is most likely suffering Malthusian effects in subtler ways like higher incidence of child mortality; higher maternal mortality rates. According to WHO a Nigerian woman has a 1 in 22 lifetime risk of dying during pregnancy, childbirth or postpartum/post-abortion; whereas in the most developed countries, the lifetime risk is 1 in 4900 [4]; higher incidences of malnutrition and poverty, Nigeria in 2018 became the poverty capital of the world by having the highest number of poor people, overtaking India [5], The graph below shows that Africa will dominate the poverty rankings by 2030; and finally, a general lower quality of life. Moreover, when you combine projections of Africa’s population for this century with the continent’s penchant for fitful and intermittent economic development, the spectre of a Malthusian catastrophe looms ever larger, but first some African population history.

In 1914 according to the best estimates, Africa’s entire population was 124 million and that includes North Africa. Today it is 1.34 billion. Compared to Africa’s roughly eleven-fold increase in population, Asia’s population increased by “only” between 3 and 4 times - China’s merely tripled and India’s increased by 4.5 times [6]. In 1960, at Nigeria’s independence, Lagos had just 200,000 people. More than half a century later it has grown 100-fold to around 20m making it one of the top ten most populous cities in the world [7]. Of course, a lot of Lagos’ growth is fueled by migration from other parts of Nigeria, still by any measure, those numbers are nothing short of spectacular.

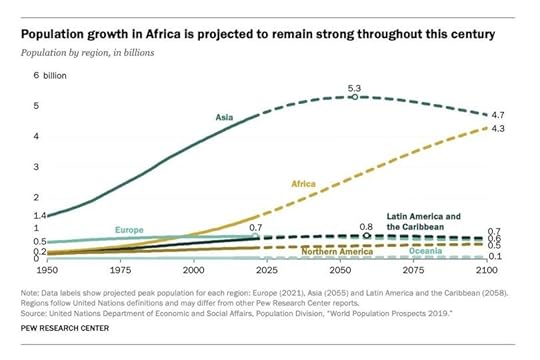

Now for future projections, most forecasts put the world’s population at roughly 11 billion by the end of the century [8]. In the period from now till the end of the century, Africa’s population is expected to grow from 1.34 billion to about 4.3 billion [9]. That is roughly about an additional 3 billion Africans. In the same timeframe, Asia’s population is projected to increase by a billion, while the populations of Europe, North and South America ae projected to remain roughly the same [10]. So all the increase is projected to come from Africa and Asia alone, with Africa producing 75% of the increase, with most of this growth coming from Sub-Saharan Africa. The graph below captures the phenomena well:

Think about what this means in terms of existing resources and infrastructure (health, education, housing, energy, transport etc.). A quadrupling of Africa’s population will indicate a need to quadruple the amount of these resources just to maintain the already inadequate levels of basic services

and amenities. Combined with an annual shortfall of 52–64% in financing for infrastructure needs in Africa (estimated at US$130 billion to 170 billion) [11], we would have the makings of a highly stressful situation possibly of Malthusian proportions.

Some of you might be wondering why the populations of the west will not budge at all. It is because they are the beneficiaries of what is called the demographic transition. I will explain it in my next post.

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this post with as many people as possible and please check out my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe on Amazon. Thank you

References:

1. Wikipedia article on Malthusianism https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malthus...

2. Wikipedia article on Demographic Transition https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demogra...

3. Wikipedia article on Malthusianism https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malthus...

4. Tooze, Adam Dec 17 2020 ‘Nigeria at a crossroads?’ Chartbook 10 https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/char...

5. Bukola Adebayo cnn.com Nigeria overtakes India in extreme poverty ranking

6. Tooze, Adam May 14 2022 ‘Youth Quake. Why African demography should matter to the world’ Chartbook 121 https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/char...

7. Tooze, Adam Dec 17 2020 ‘Nigeria at a crossroads?’ Chartbook 10 https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/char...

8. Rosling, Hans. 2018Factulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About The World – And Why Things Are Better Than You Think. UK:Sceptre

9. Tooze, Adam Dec 17 2020 ‘Nigeria at a crossroads?’ Chartbook 10 https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/char...

10. Rosling, Hans. 2018 Factulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About The World – And Why Things Are Better Than You Think. UK:Sceptre

11. Jesse G, Madden P. Figures of the week: Africa’s infrastructure needs are an investment opportunity; Brookings Institution. 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa...

Published on February 27, 2023 22:08

February 13, 2023

Just Two Graphs to explain global wealth and poverty. That’s all. Nothing more

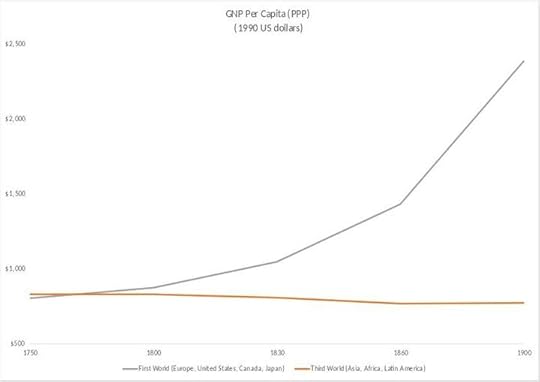

The graph above shows the Gross National Product (GNP) per capita, Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) of the First World (here Europe, United States, Canada, and Japan) and the Third World (Asia, Africa, and Latin America) between the years 1750 (The dawn of the Industrial Revolution) and 1900 (Beginning of the 20th century). Since I have thrown around quite a bit of technical terms, I will explain.

GNP per capita refers to the total value of the goods and services produced by a country or region including the income it derives from foreign investments and exports divided by the number of people living there. Now the value of a dollar in one country may not be necessarily equal to the value of a dollar in another country in the sense that a dollar may buy more goods and services in one country compared to another. So Purchasing Power Parity is a technique that economists have come up with to equalize the value of a currency across countries so that they can properly compare purchasing power across countries. So all told, you can think of GNP per capita as a measure of how wealthy the average citizen of a country or region is. I think this graph makes clear the great divergence in wealth, and the upward trajectory of the First World as they reaped the benefits of industrialization. The Industrial Revolution took off in Britain around 1760. The United States and Germany would join the industrial bandwagon in the early decades of the 19th century (Both would eventually overtake Britain largely because of their willingness to make use of deeper scientific principles that British engineers at the time resisted), Japan would join in the late decades of the 19th century around 1875. You probably also noticed the very similar starting points as regards the wealth of the two regions.

Here is the second graph:

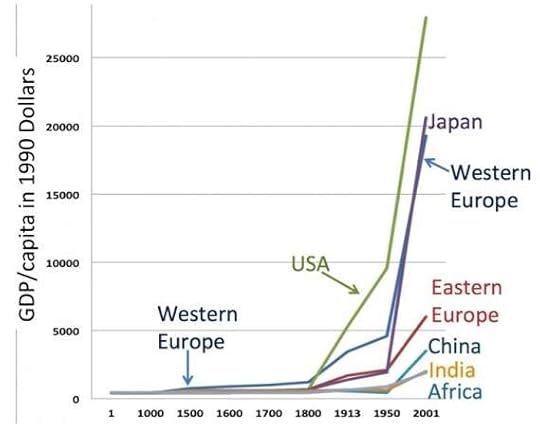

This second graph shows the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita from the time of the birth of the Lord, Jesus Christ roughly 2,000 years ago to the year 2001. GDP per capita refers to the total value of the goods and services produced by a country or region excluding the income it derives from foreign investments and exports divided by the number of people living there. So mathematically speaking:

GDP = GNP – Income derived from exports and foreign investment.

GDP is also a measure of the level of prosperity experienced by the average citizen of a country or region.

You cannot fail to notice how GDP per capita remains largely flat for every part of the world for about 1,800 years from the time that Jesus Christ literally walked on the face of the earth to the year 1800. You also cannot also fail to notice the significant jumps in GDP per capita experienced by Western Europe, USA and Japan at points that closely match the take-off of the Industrial Revolution in those regions. You might have also noticed that the graphs of U.S.A, Western Europe and Japan resemble the first two sections of an “S-Curve” (The third section of an S-Curve would typically be a gentle decline or flattening out). I explained S-Curves in a previous post. It just goes to show that economic development is not random or magical. There is a science to it, a science that as Africans, we do not seem to have grasped. This graph has some unflattering information. In 1913, that’s 110 years ago, America’s GDP per capita had already crossed $5,000. For comparison, Nigeria’s GDP per capita was $5,238 in 2018 [3]. One more important fact to note. The main economic activity for the thousands of years before the Industrial Revolution, was agriculture. So when African politicians shout agriculture, you now have a picture of what average wealth will look like.

Of course, the jump in productivity brought on by the Industrial Revolution didn’t spring out of nowhere. By the way, you should know that nothing determines the level of wealth in a country as much as the growth in productivity (It is NOT natural resources. Please get that out of your head). And nothing drives the growth of productivity like the development of science and technology in service of economic growth that tends to happen when a country successfully industrializes. As I was saying, the jump in productivity the west, brought on by the Industrial Revolution, didn’t spring out of nowhere. The seeds were first sown in the 10th century, 800 years before the Industrial Revolution took off starting with the large scale urbanization that created Europe’s first cities [1]. Other critical events include the establishment of a legal code for securing property rights that happened in the same time period of 900-1300 that the large-scale migrations to the cities was happening [2]; The invention of the Gutenberg printing press in the 15th century. We shouldn’t fall into the trap of thinking of this innovation as mundane because of the ease with which we print books today. The Gutenberg Press ranks up there with the world’s greatest inventions, from the invention of the wheel, to the steam engine, the discovery of electricity, right up to the invention of the internet; Further critical events include the development of Capitalism; The Scientific Revolution of which the Newtonian system of Mechanics was the pinnacle, and the movement known as the Enlightenment, which was a movement to bring scientific reasoning to the realm of human/social affairs modeled after the Scientific Revolution. All these and more were critical to the take-off of the Industrial Revolution.

I started this write-up saying just two graphs…I lied. If that line sounds familiar, you probably heard it in the movie “Commando” starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Oh God…I think I just inadvertently told you how old I am.

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this with as many people as possible. Also check out my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe.

References:

1. Luiten Van Zanden, Jan. 2009 The long road to the Industrial Revolution: The European Economy in a Global Perspective, 1000–1800. Leiden: Brill

2. Ibid

3. The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison...

Published on February 13, 2023 20:47

February 7, 2023

This guy and your industrialization…how do you want to industrialize without power??

I eventually had to come to this topic. There was no avoiding it. Everyone knows that steady, affordable power will be a crucial input to any serious industrialization effort. But what might not be well known is a fact I stumbled on recently as to why our efforts to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to our power sector has failed in recent years. Turns out the foreign investors (local ones too) have passed on the opportunity to invest in our power sector because in their estimates there is little demand for power in the country [1]. I can hear you screaming, “what do they mean that there is no demand for power?..over 200 million people frustrated with incessant power outages every day, how can they say there is no demand?” Hold your horses and I will explain.

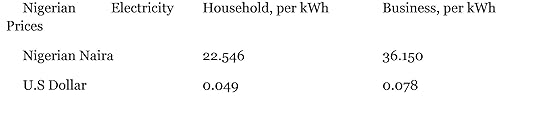

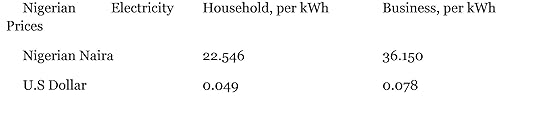

Generally, the world over, domestic demand is only a small fraction of total power demand, the bulk of it comes from industrial demand. With our industrial sector in a near comatose state (No doubt partly brought on by the lack of power. Poor or absent industrial policies will be another major factor), the scenario is perceived as one that would lead to poor Returns On Investment (ROI), should they, the investors, invest in the sector. You might argue that but if the investments were made, industries would spring up and investors would be able to recoup investments. It is at this point that the issue of pricing of electricity comes in. The table below shows the pricing of electricity in Nigeria, in both naira and dollars and for both household and business consumers, as of June 2022. The prices are from the site, globalpetrolprices.com:

The site also points out that the global average is about 0.161 USD per kWh for households and 0.167 USD for businesses. That is, the global average is about 3 times the Nigerian price for households and about 2 times the Nigerian price for businesses.

These figures tally with what I heard an investment banker express sometime between 2014 and 2017, when I used to attend an annual conference on power that I think was organized by a Dubai-based outfit. I remember him saying that consumers were being charged 36 Naira per kWh, though I don’t remember him specifying whether he was talking about households or businesses. He also went on to say that the generating companies were generating power at a cost of 72 Naira per kWh, that is a cost twice than what they are charging consumers. So they are not even covering their operating costs.

This situation tends to be common in developing countries, largely because power utilities in developing countries have tended to be publicly owned and so through them, governments in developing countries are trying to achieve social, as well as economic goals. In this case, social goals would include universal access to energy in general and to electricity in particular because access to energy is critical for development and improving living standards. As noble as these intentions are, the harsh reality is that because of the generally low purchasing power of the citizens of developing countries, power utilities in those countries are often forced into the circumstances described above. This brings on many problems; they can’t keep the inventory levels they ought to keep; they can’t do essential regular maintenance; they are forced to request government subsidies, this of course takes resources away from other critical areas of the economy; they often compelled to take to borrowing which imposes a heavy debt service burden in later years [2].

Funding infrastructure is not cheap and this is especially so for power. I happened to have been involved some years back (2014-2015) with the Centre for Petroleum, Energy Economics and Law (CPEEL), which is a MacArthur Foundation Regional Centre of Excellence based at the University of Ibadan. While there they conducted a study on universal electricity access (Disclaimer: I was not involved in the study). In the study, they estimated that for Nigeria to achieve universal electricity access, the power sector would have to receive investments of about $300 billion over a period of 30 years [3]. That tallies with another estimate I came across at roughly the same time from a report by PriceWaterhouseCoopers that mentioned needing investments on the order of about $10 billion every year. Other infrastructure finance material I have come across suggest that in the US, spending on power is on the order of $100 billion every year [4]. This makes the $16 billion that Obasanjo allegedly spent during his tenure look like mere pittance. Moreover, Obasanjo’s Senior Special Adviser on Power, Foluseke Somolu claims that for those 8 years, the monies disbursed for power investment cumulatively add up to just $5.1 billion [5]. At this point, I would like to give a word of advice if I may. Please note that in economic affairs, a single number, no matter how big it seems, is almost meaningless. You need at least a 2nd number or some sort of benchmark to make sense of the 1st number.

So what to do? We seem to be between the devil and the deep blue sea. Industry needs power to thrive, and in our case, we need industrial activity to attract investment to the power sector. A really frustrating catch-22 situation. As bleak as it sounds, there is reason to hope. Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo are a Nobel Prize winning husband and wife team in the economics department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which is reputed to have the best economics department in the world. They specialize in developing country issues. In their book Good Economics for Hard Times, they cite studies which show that while developing countries generally lack resources, their GDP per capita is even lower than what this lack of resources would predict. In other words, poor countries are poor in substantial part because they make less good use of the resources they do have [6]. My guess as to why this is so will be a combination of knowledge gaps, communication gaps, relative lack of organizational capability, lack of political will, corruption and absent or uninformed public policies. Making progress in these areas though hard, is clearly possible. As for the catch-22 situation between power and industry, it seems the two will have to co-evolve.

Co-evolution is an established concept in evolutionary biology. Perhaps its most recognizable form is the symbiotic relationship between flowers and the insects that pollinate them, where both co-evolve with and co-adapt to one another for their mutual benefit. Specific examples of this include flowers baiting insects with pollen and nectar. The insects while feasting on these, in return pollinate the flowers. Some flowers go as far as mimicking female members of the insect species. This attracts and deceives the males into carrying out pseudo-copulation. In the process, the flowers are pollinated [7]. Another well-known instance of co-evolution are predator-prey relationships. Predators and prey interact and coevolve: the predator to catch the prey more effectively, the prey to escape. Yet another example of co-evolution would be host-parasite relationships. One particular example of this that should resonate in this part of the world is the relationship between man and the malaria parasite. There is an evolutionary arms race between us and the malaria parasite similar to the nuclear arms race between the now defunct USSR and the USA during the Cold War. In this arms race, there is an ongoing struggle between competing sets (here, man and plasmodium) of co-evolving genes and behavioral traits that develop escalating adaptations and counter-adaptations against each other [8]. This arms race goes a long way to explain why chloroquine is no longer an effective remedy against malaria [9]. Also, the SS genotype was a genetic adaptation on our part long ago to provide protection against malaria, though as we all know, with grave consequences [10].

Co-evolution has made its way as a concept from biology into economics (among other disciplines) in the sub-discipline known as evolutionary economics. Coevolution in economic systems plays a key role in the dynamics of contemporary societies. Coevolution operates when, considering several evolving realms within a socioeconomic system, these realms mutually shape each other’s development [11]. For our case, a starting point could be aggressive policies that unlock low hanging fruits in some industrial sectors. I gave the example of the paper industry in one of my previous posts. This is by no means the only example. If such policies are backed up by political will, they should create formal employment opportunities. This helps reduce the size of the informal economy. I had discussed the problems of the informal economy in another previous post. Reducing the informal economy will broaden the tax base, meaning more revenue for government. More importantly, it would mean greater purchasing power among the populace and a heightened ability to afford market-friendly electricity tariffs. Market-friendly tariffs will serve as an inducement to potential investors to set up the public private partnerships so desperately needed in the power sector because completely publicly funded infrastructure in this day and age is simply unsustainable. The process, it should be obvious is a slow and iterative one but then, at some point in adult life, one should learn to accept that economic development is not magic.

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this article with as many people as possible and check out my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe. Thank you.

References

1. Capt Samuel Akinyele Caulcrick. August 2017 ‘Nigeria, Warehouse of imported goods’, punchng.com: https://punchng.com/nigeria-warehouse...

2. A. Heron. Winter 1985 IAEA Bulletin ‘Financing electric power in developing countries’

3. Iwayemi, Akin et al. 2014 Towards Sustainable Universal Electricity Access in Nigeria. Ibadan Patrick Edobor and Associates

4. Grigg, Neil S. 2010 Infrastructure Finance: The Business of Infrastructure for a Sustainable Future. New Jersey John Wiley & Sons

5. Obasanjo, Olusegun 2014 My Watch: Political and Public Affairs. Yaba, Lagos. Prestige

6. Banerjee, Abhijit Duflo, Esther 2019 Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems. UK Penguin Random House

7. Wikipedia article on Co-Evolution https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coevolu...

8. Wikipedia article on Evolutionary Arms Race https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evoluti...

9. Apr 2014 ‘The evolution of chloroquine’ www.labonline.com.au https://www.labonline.com.au/content/...

10. Mia Rozenbaum June 2019 ‘How sickle cell protects against Malaria’ understandinganimalresearch.org.uk https://www.understandinganimalresear...

11. Almudi, Isabel Fatas-Villafranca, Francisco 2021 Co-Evolution in Economic Systems. UK Cambridge University Press

Generally, the world over, domestic demand is only a small fraction of total power demand, the bulk of it comes from industrial demand. With our industrial sector in a near comatose state (No doubt partly brought on by the lack of power. Poor or absent industrial policies will be another major factor), the scenario is perceived as one that would lead to poor Returns On Investment (ROI), should they, the investors, invest in the sector. You might argue that but if the investments were made, industries would spring up and investors would be able to recoup investments. It is at this point that the issue of pricing of electricity comes in. The table below shows the pricing of electricity in Nigeria, in both naira and dollars and for both household and business consumers, as of June 2022. The prices are from the site, globalpetrolprices.com:

The site also points out that the global average is about 0.161 USD per kWh for households and 0.167 USD for businesses. That is, the global average is about 3 times the Nigerian price for households and about 2 times the Nigerian price for businesses.

These figures tally with what I heard an investment banker express sometime between 2014 and 2017, when I used to attend an annual conference on power that I think was organized by a Dubai-based outfit. I remember him saying that consumers were being charged 36 Naira per kWh, though I don’t remember him specifying whether he was talking about households or businesses. He also went on to say that the generating companies were generating power at a cost of 72 Naira per kWh, that is a cost twice than what they are charging consumers. So they are not even covering their operating costs.

This situation tends to be common in developing countries, largely because power utilities in developing countries have tended to be publicly owned and so through them, governments in developing countries are trying to achieve social, as well as economic goals. In this case, social goals would include universal access to energy in general and to electricity in particular because access to energy is critical for development and improving living standards. As noble as these intentions are, the harsh reality is that because of the generally low purchasing power of the citizens of developing countries, power utilities in those countries are often forced into the circumstances described above. This brings on many problems; they can’t keep the inventory levels they ought to keep; they can’t do essential regular maintenance; they are forced to request government subsidies, this of course takes resources away from other critical areas of the economy; they often compelled to take to borrowing which imposes a heavy debt service burden in later years [2].

Funding infrastructure is not cheap and this is especially so for power. I happened to have been involved some years back (2014-2015) with the Centre for Petroleum, Energy Economics and Law (CPEEL), which is a MacArthur Foundation Regional Centre of Excellence based at the University of Ibadan. While there they conducted a study on universal electricity access (Disclaimer: I was not involved in the study). In the study, they estimated that for Nigeria to achieve universal electricity access, the power sector would have to receive investments of about $300 billion over a period of 30 years [3]. That tallies with another estimate I came across at roughly the same time from a report by PriceWaterhouseCoopers that mentioned needing investments on the order of about $10 billion every year. Other infrastructure finance material I have come across suggest that in the US, spending on power is on the order of $100 billion every year [4]. This makes the $16 billion that Obasanjo allegedly spent during his tenure look like mere pittance. Moreover, Obasanjo’s Senior Special Adviser on Power, Foluseke Somolu claims that for those 8 years, the monies disbursed for power investment cumulatively add up to just $5.1 billion [5]. At this point, I would like to give a word of advice if I may. Please note that in economic affairs, a single number, no matter how big it seems, is almost meaningless. You need at least a 2nd number or some sort of benchmark to make sense of the 1st number.

So what to do? We seem to be between the devil and the deep blue sea. Industry needs power to thrive, and in our case, we need industrial activity to attract investment to the power sector. A really frustrating catch-22 situation. As bleak as it sounds, there is reason to hope. Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo are a Nobel Prize winning husband and wife team in the economics department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which is reputed to have the best economics department in the world. They specialize in developing country issues. In their book Good Economics for Hard Times, they cite studies which show that while developing countries generally lack resources, their GDP per capita is even lower than what this lack of resources would predict. In other words, poor countries are poor in substantial part because they make less good use of the resources they do have [6]. My guess as to why this is so will be a combination of knowledge gaps, communication gaps, relative lack of organizational capability, lack of political will, corruption and absent or uninformed public policies. Making progress in these areas though hard, is clearly possible. As for the catch-22 situation between power and industry, it seems the two will have to co-evolve.

Co-evolution is an established concept in evolutionary biology. Perhaps its most recognizable form is the symbiotic relationship between flowers and the insects that pollinate them, where both co-evolve with and co-adapt to one another for their mutual benefit. Specific examples of this include flowers baiting insects with pollen and nectar. The insects while feasting on these, in return pollinate the flowers. Some flowers go as far as mimicking female members of the insect species. This attracts and deceives the males into carrying out pseudo-copulation. In the process, the flowers are pollinated [7]. Another well-known instance of co-evolution are predator-prey relationships. Predators and prey interact and coevolve: the predator to catch the prey more effectively, the prey to escape. Yet another example of co-evolution would be host-parasite relationships. One particular example of this that should resonate in this part of the world is the relationship between man and the malaria parasite. There is an evolutionary arms race between us and the malaria parasite similar to the nuclear arms race between the now defunct USSR and the USA during the Cold War. In this arms race, there is an ongoing struggle between competing sets (here, man and plasmodium) of co-evolving genes and behavioral traits that develop escalating adaptations and counter-adaptations against each other [8]. This arms race goes a long way to explain why chloroquine is no longer an effective remedy against malaria [9]. Also, the SS genotype was a genetic adaptation on our part long ago to provide protection against malaria, though as we all know, with grave consequences [10].

Co-evolution has made its way as a concept from biology into economics (among other disciplines) in the sub-discipline known as evolutionary economics. Coevolution in economic systems plays a key role in the dynamics of contemporary societies. Coevolution operates when, considering several evolving realms within a socioeconomic system, these realms mutually shape each other’s development [11]. For our case, a starting point could be aggressive policies that unlock low hanging fruits in some industrial sectors. I gave the example of the paper industry in one of my previous posts. This is by no means the only example. If such policies are backed up by political will, they should create formal employment opportunities. This helps reduce the size of the informal economy. I had discussed the problems of the informal economy in another previous post. Reducing the informal economy will broaden the tax base, meaning more revenue for government. More importantly, it would mean greater purchasing power among the populace and a heightened ability to afford market-friendly electricity tariffs. Market-friendly tariffs will serve as an inducement to potential investors to set up the public private partnerships so desperately needed in the power sector because completely publicly funded infrastructure in this day and age is simply unsustainable. The process, it should be obvious is a slow and iterative one but then, at some point in adult life, one should learn to accept that economic development is not magic.

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this article with as many people as possible and check out my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe. Thank you.

References

1. Capt Samuel Akinyele Caulcrick. August 2017 ‘Nigeria, Warehouse of imported goods’, punchng.com: https://punchng.com/nigeria-warehouse...

2. A. Heron. Winter 1985 IAEA Bulletin ‘Financing electric power in developing countries’

3. Iwayemi, Akin et al. 2014 Towards Sustainable Universal Electricity Access in Nigeria. Ibadan Patrick Edobor and Associates

4. Grigg, Neil S. 2010 Infrastructure Finance: The Business of Infrastructure for a Sustainable Future. New Jersey John Wiley & Sons

5. Obasanjo, Olusegun 2014 My Watch: Political and Public Affairs. Yaba, Lagos. Prestige

6. Banerjee, Abhijit Duflo, Esther 2019 Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems. UK Penguin Random House

7. Wikipedia article on Co-Evolution https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coevolu...

8. Wikipedia article on Evolutionary Arms Race https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evoluti...

9. Apr 2014 ‘The evolution of chloroquine’ www.labonline.com.au https://www.labonline.com.au/content/...

10. Mia Rozenbaum June 2019 ‘How sickle cell protects against Malaria’ understandinganimalresearch.org.uk https://www.understandinganimalresear...

11. Almudi, Isabel Fatas-Villafranca, Francisco 2021 Co-Evolution in Economic Systems. UK Cambridge University Press

Published on February 07, 2023 21:56

January 3, 2023

The Rise of the Electric Car…. The Fall of Petroleum? The Scariness of “S-Curve” Growth and Why Covid 19 is the Twin Sister of Tech

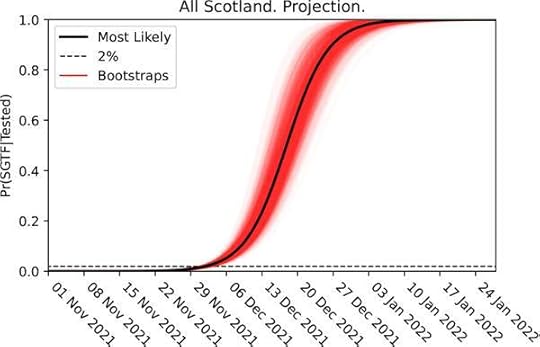

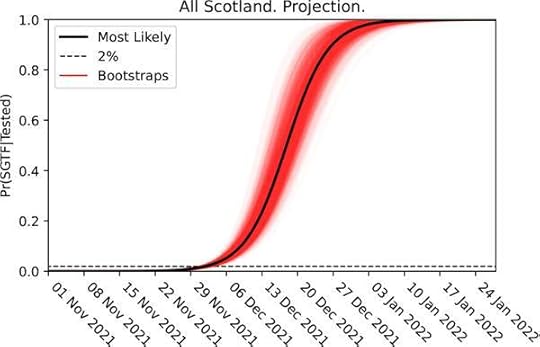

On the 1st of December 2019, The first case of Covid 19 was discovered in Wuhan, the provincial capital of Hubei, a province in China. Within three months it had spread to virtually every corner of the globe. How did it spread that fast? The answer is the “S-curve”. The S-curve is a mathematical function that describes processes that start off relatively slowly but after reaching some critical point begin to accelerate greatly. The graph below depicts the spread of the Omicron variant of Covid 19 in Scotland:

Source: Joint UNIversity Pandemic and Epidemic Response (JUNIPER) modelling consortium UK

Please note that the graph depicted above is a projection, not the actual spread. It was made when Omicron made up less than 2% of the cases in Scotland. The actual spread would later be shown to match this projection.

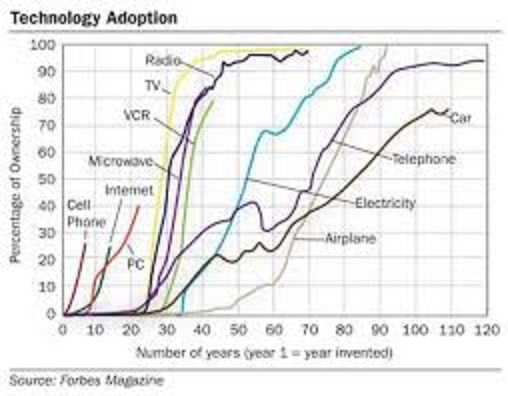

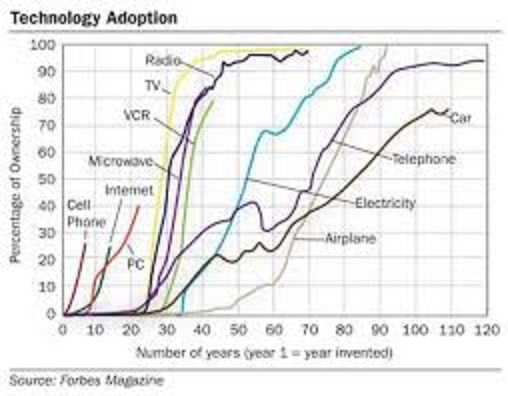

Formally speaking, the S-curve is known in mathematics as the “Logistic Growth Function”. The Logistic Growth Function has many applications. It is heavily used in demography and ecology for modeling population growth; it is used in Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the design of Neural Networks (Neural Networks are AI software applications modeled after the human brain); it is used in psychology for the construction of scholastic achievement tests like the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) taken by American students planning to enter university, and also tests for determining personality types that all those fancy companies like to use to determine whether you will be a good fit; it is used in medicine for modeling the growth of cancerous tumors, in linguistics for modeling how languages change over time (Who would have thought that you could apply mathematics to english??); in agriculture for modeling crop response to change in growth factors, and it can be used to model….technology adoption. The following graph shows the adoption patterns of those technologies that have done the most to shape modern life:

I cannot at this time, explain why the S-curve applies to the spread to disease epidemics like Covid and all those other applications but I can explain its applicability to technology adoption. Technology adopters can be divided into two groups; innovators and imitators [1]. The innovators are those that make their purchase decisions independently while the imitators make their purchase decisions only after interacting with previous buyers. The critical point where relatively fast adoption begins, is that point where imitators begin to buy.

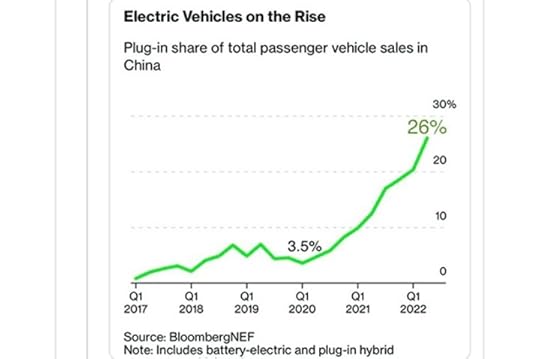

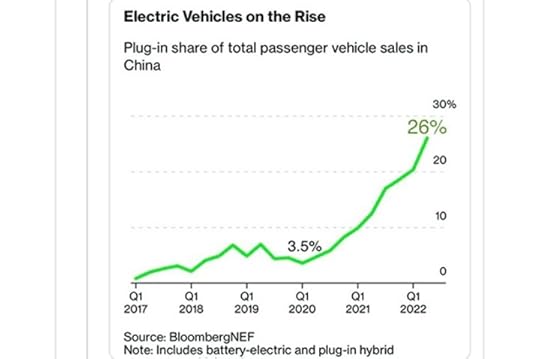

Now, information that I recently came across, suggest that electric car adoption in the major car markets of the US, Europe and China (particularly China), have recently reached that critical point, the critical point being, according to Bloomberg analysis, 5% of new car sales. For a number of European countries and China (possibly as high as 26% in China), the figures have crossed 10% [2]. The US, Europe and China together constitute roughly two-thirds of the global car market.

So has China reached the tipping point? Take a look at this graph:

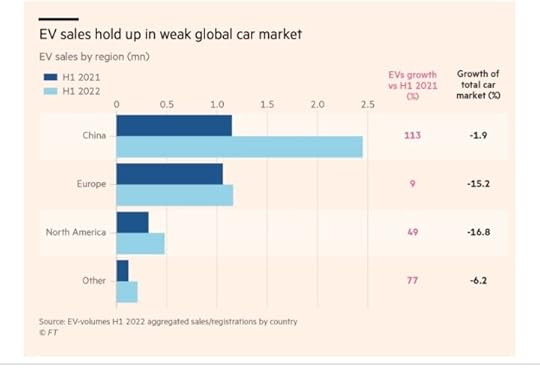

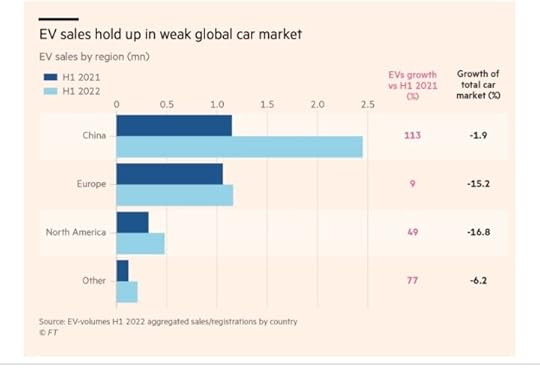

While I feel that it is still too early to say, looking at the graph, it sure does look like it. According to the graph, Electric Vehicles (EV) accounted for 26% of all cars sales in China in the first quarter of 2022, up from 3.5% in the first quarter of 2020. While it is noted that the figure includes hybrids, it has also been noted by industry watchers that China mostly skipped the hybrid phase and went straight to fully electric. Here is another one:

Now this graph makes for scary reading. Not just from China, from everywhere. In the first half of 2022, the sale of EVs in China grew by 113% compared to the first half of 2021, despite the fact that the overall car market shrank by 1.9%. Now the figures for Europe may not look too impressive, sales just grew by 9%, but you have to take note of the fact that the overall car market shrank by a whopping 15.2%. The scary factor ramps up again when you look at North America. EV sales grew by an impressive 49% while the overall car market shrank by 16.8%. That’s just mind boggling. Perhaps the scariest of all, In the rest of the world, EV sales grew by 77% while the overall car market shrank by 6.2% over the same period. Why I said that perhaps, the growth in the rest of the world is the scariest is because some time back, I read a newspaper article where Nigerian government officials felt that the growth projection for EVs in the West was too “futuristic”, and that even if true, that they will sell their oil to other countries [3]. If we can trust this data (The source is the Financial Times of London), I can’t help wondering “Sell to who exactly?”. I realize oil has other uses than fueling cars, but 90% of vehicular fuel needs are met by oil [4], so in the event of EVs going mainstream, the loss of revenue is bound to be substantial. I will readily concede that even if we have truly entered the stage of the rapid growth of the S-curve, it will still take at least, a couple of decades for EVs to go mainstream.

However, it doesn’t take EVs fully going mainstream for us to experience serious pain, the global oil glut of 2014-2015 should have taught us that. The oil glut was caused by production of shale oil by the US and Canada reaching critical volumes, slowing growth in China and hence a fall in demand for commodities across board and perhaps most importantly, restraint of long-term demand as global environmental policy promotes fuel efficiency and steers an increasing share of energy consumption away from fossil fuels [5]. The uptake of EVs definitely keys into that.

There is a potential outcome in the long-term, that is even more worrisome for me but before I get into that, I need to explain what car companies are doing to their production systems. Most car companies have plans to go fully electric or substantially electric between 2030 and 2040. If you want the details check out my book Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe . To hit those targets, they are retooling their factories and reconfiguring their supply-chains to optimize for EV production [6]. The more they do this, the less they can produce petrol cars. It is not far-fetched to think that even we might be forced to buy EVs before we are ready (Unless you are optimistic that we will solve our electricity grid problems in 20 years). Given that most of the cars purchased in Nigeria are second-hand, the car companies have absolutely no incentive to keep producing petrol cars for us since none of the proceeds for second-hand sales goes to them. Practically speaking, from their point of view, the car market in Nigeria does not exist. I don’t know if by then the likes of Innoson might be able to ramp up production to meet demand. Of course petrol cars will still be in circulation a good while after that but at some point they must run out. So while our government officials talk about selling oil to other countries, we might be in the embarrassing situation of not being able to sell our oil to ourselves. Let me make clear that this is only a plausible conjectured scenario, not inevitability and only plausible in the long term.

I hope this makes clear that the lack of industrialization is our biggest problem. This is because non-industrial countries like ours are simply not in control of their own economies. It is possible that something could stall the growth of EVs. One could be not enough lithium deposits to make lithium-ion car batteries but there are potential long term alternatives, some are sodium-ion, lithium-sulphur [7], calcium-ion, and graphene (carbon) [8]. There could be problems with the sourcing of other metals like cobalt, nickel required for electric car production and for other uses in general. It is too early to say how the EV industry will fix all these supply-chain problems.

I wrote this piece not just to enlighten people about the emerging EV trend but more importantly, to show how science can be used to make sense of the world around us. The regularities that science uncovers in nature and in society if harnessed properly, can be used to make the world a better place for you and for me…How did I go from Covid 19 and electric cars to singing Michael Jackson??

BEFORE YOU GO: Please I would like to ask that you share this article with as many people as possible. Thanks and God bless…and by the way, Happy New Year!!

References

1. Rohit Tripathi. June 2021 ‘Spread of infectious diseases, consumer goods adoption, and technology S curves’ www.the-future-of-commerce.com: https://www.the-future-of-commerce.co...

2. Bloomberg Updated 10 July 2022 “US crosses the electric car tipping point for mass adoption”, auto.hindustantimes.com https://auto.hindustantimes.com/auto/...

3. Kingsley Jeremiah. June 2021 ‘FG adamant on fossil fuels despite $13tr projected global losses’ guardian.ng: https://bit.ly/3irn8HA

4. Petroleum article on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petroleum

5. 2010s oil glut on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2010s_o...

6. Bloomberg Updated 10 July 2022 “US crosses the electric car tipping point for mass adoption”, auto.hindustantimes.com https://auto.hindustantimes.com/auto/...

7. James Scoltock 21 Sept 2022 “The Big Battery Challenge: 3 potential alternatives to Lithium” imeche.org https://www.imeche.org/news/news-arti...

8. Claudia Alemany Castilla 14 Oct 2022 “Calcium may make a better battery than Lithium” engineeringforchange.com https://www.engineeringforchange.org/...

Source: Joint UNIversity Pandemic and Epidemic Response (JUNIPER) modelling consortium UK

Please note that the graph depicted above is a projection, not the actual spread. It was made when Omicron made up less than 2% of the cases in Scotland. The actual spread would later be shown to match this projection.

Formally speaking, the S-curve is known in mathematics as the “Logistic Growth Function”. The Logistic Growth Function has many applications. It is heavily used in demography and ecology for modeling population growth; it is used in Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the design of Neural Networks (Neural Networks are AI software applications modeled after the human brain); it is used in psychology for the construction of scholastic achievement tests like the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) taken by American students planning to enter university, and also tests for determining personality types that all those fancy companies like to use to determine whether you will be a good fit; it is used in medicine for modeling the growth of cancerous tumors, in linguistics for modeling how languages change over time (Who would have thought that you could apply mathematics to english??); in agriculture for modeling crop response to change in growth factors, and it can be used to model….technology adoption. The following graph shows the adoption patterns of those technologies that have done the most to shape modern life:

I cannot at this time, explain why the S-curve applies to the spread to disease epidemics like Covid and all those other applications but I can explain its applicability to technology adoption. Technology adopters can be divided into two groups; innovators and imitators [1]. The innovators are those that make their purchase decisions independently while the imitators make their purchase decisions only after interacting with previous buyers. The critical point where relatively fast adoption begins, is that point where imitators begin to buy.

Now, information that I recently came across, suggest that electric car adoption in the major car markets of the US, Europe and China (particularly China), have recently reached that critical point, the critical point being, according to Bloomberg analysis, 5% of new car sales. For a number of European countries and China (possibly as high as 26% in China), the figures have crossed 10% [2]. The US, Europe and China together constitute roughly two-thirds of the global car market.

So has China reached the tipping point? Take a look at this graph:

While I feel that it is still too early to say, looking at the graph, it sure does look like it. According to the graph, Electric Vehicles (EV) accounted for 26% of all cars sales in China in the first quarter of 2022, up from 3.5% in the first quarter of 2020. While it is noted that the figure includes hybrids, it has also been noted by industry watchers that China mostly skipped the hybrid phase and went straight to fully electric. Here is another one:

Now this graph makes for scary reading. Not just from China, from everywhere. In the first half of 2022, the sale of EVs in China grew by 113% compared to the first half of 2021, despite the fact that the overall car market shrank by 1.9%. Now the figures for Europe may not look too impressive, sales just grew by 9%, but you have to take note of the fact that the overall car market shrank by a whopping 15.2%. The scary factor ramps up again when you look at North America. EV sales grew by an impressive 49% while the overall car market shrank by 16.8%. That’s just mind boggling. Perhaps the scariest of all, In the rest of the world, EV sales grew by 77% while the overall car market shrank by 6.2% over the same period. Why I said that perhaps, the growth in the rest of the world is the scariest is because some time back, I read a newspaper article where Nigerian government officials felt that the growth projection for EVs in the West was too “futuristic”, and that even if true, that they will sell their oil to other countries [3]. If we can trust this data (The source is the Financial Times of London), I can’t help wondering “Sell to who exactly?”. I realize oil has other uses than fueling cars, but 90% of vehicular fuel needs are met by oil [4], so in the event of EVs going mainstream, the loss of revenue is bound to be substantial. I will readily concede that even if we have truly entered the stage of the rapid growth of the S-curve, it will still take at least, a couple of decades for EVs to go mainstream.

However, it doesn’t take EVs fully going mainstream for us to experience serious pain, the global oil glut of 2014-2015 should have taught us that. The oil glut was caused by production of shale oil by the US and Canada reaching critical volumes, slowing growth in China and hence a fall in demand for commodities across board and perhaps most importantly, restraint of long-term demand as global environmental policy promotes fuel efficiency and steers an increasing share of energy consumption away from fossil fuels [5]. The uptake of EVs definitely keys into that.

There is a potential outcome in the long-term, that is even more worrisome for me but before I get into that, I need to explain what car companies are doing to their production systems. Most car companies have plans to go fully electric or substantially electric between 2030 and 2040. If you want the details check out my book Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe . To hit those targets, they are retooling their factories and reconfiguring their supply-chains to optimize for EV production [6]. The more they do this, the less they can produce petrol cars. It is not far-fetched to think that even we might be forced to buy EVs before we are ready (Unless you are optimistic that we will solve our electricity grid problems in 20 years). Given that most of the cars purchased in Nigeria are second-hand, the car companies have absolutely no incentive to keep producing petrol cars for us since none of the proceeds for second-hand sales goes to them. Practically speaking, from their point of view, the car market in Nigeria does not exist. I don’t know if by then the likes of Innoson might be able to ramp up production to meet demand. Of course petrol cars will still be in circulation a good while after that but at some point they must run out. So while our government officials talk about selling oil to other countries, we might be in the embarrassing situation of not being able to sell our oil to ourselves. Let me make clear that this is only a plausible conjectured scenario, not inevitability and only plausible in the long term.

I hope this makes clear that the lack of industrialization is our biggest problem. This is because non-industrial countries like ours are simply not in control of their own economies. It is possible that something could stall the growth of EVs. One could be not enough lithium deposits to make lithium-ion car batteries but there are potential long term alternatives, some are sodium-ion, lithium-sulphur [7], calcium-ion, and graphene (carbon) [8]. There could be problems with the sourcing of other metals like cobalt, nickel required for electric car production and for other uses in general. It is too early to say how the EV industry will fix all these supply-chain problems.

I wrote this piece not just to enlighten people about the emerging EV trend but more importantly, to show how science can be used to make sense of the world around us. The regularities that science uncovers in nature and in society if harnessed properly, can be used to make the world a better place for you and for me…How did I go from Covid 19 and electric cars to singing Michael Jackson??

BEFORE YOU GO: Please I would like to ask that you share this article with as many people as possible. Thanks and God bless…and by the way, Happy New Year!!

References

1. Rohit Tripathi. June 2021 ‘Spread of infectious diseases, consumer goods adoption, and technology S curves’ www.the-future-of-commerce.com: https://www.the-future-of-commerce.co...

2. Bloomberg Updated 10 July 2022 “US crosses the electric car tipping point for mass adoption”, auto.hindustantimes.com https://auto.hindustantimes.com/auto/...

3. Kingsley Jeremiah. June 2021 ‘FG adamant on fossil fuels despite $13tr projected global losses’ guardian.ng: https://bit.ly/3irn8HA

4. Petroleum article on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petroleum

5. 2010s oil glut on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2010s_o...

6. Bloomberg Updated 10 July 2022 “US crosses the electric car tipping point for mass adoption”, auto.hindustantimes.com https://auto.hindustantimes.com/auto/...

7. James Scoltock 21 Sept 2022 “The Big Battery Challenge: 3 potential alternatives to Lithium” imeche.org https://www.imeche.org/news/news-arti...

8. Claudia Alemany Castilla 14 Oct 2022 “Calcium may make a better battery than Lithium” engineeringforchange.com https://www.engineeringforchange.org/...

Published on January 03, 2023 23:55

December 20, 2022

Agriculture is never enough…even services needs some help from manufacturing

As calls are rightly being made to diversify the Nigerian economy away from its dependence on oil, calls are being made to “return to our roots” in agriculture. While this is sensible enough on the surface, however some drilling down, particularly when you extend the analysis to the entire African continent reveals some facts that should at the very least make one feel uncomfortable. Agriculture is already the leading economic activity with about roughly 60-70% of the people being farmers, yet the continent is a net importer of food, has been so since the 1980s, with a food import bill that has been as much as $35 billion in recent years and is projected to go as high as $110 billion by 2025. To the uninitiated, this is made to look even more absurd when you consider that in America, only 1.3% of the people are farmers yet they produce enough to feed over 300 million people and still manage to export roughly 20% of their agricultural produce [1].

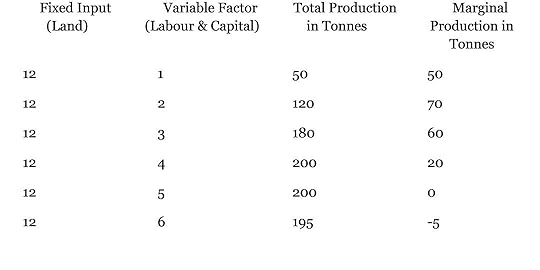

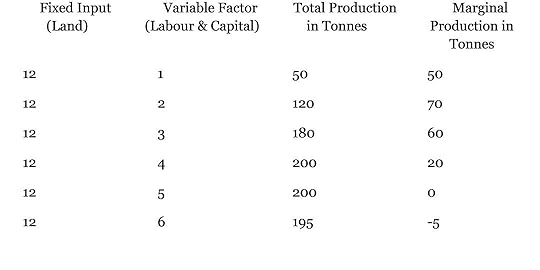

A decent economist would probably not be surprised this. Economists have long known that the ‘Law of Diminishing Returns’ applies much more strongly to agriculture than to other major areas of economic activity like manufacturing and services [2]. Alfred Marshall, one of the founders of neoclassical economics, defined the law of diminishing returns as applied to agriculture, as follows:

“With each additional input of labour and capital applied to a given piece of land, total product increases at a diminishing rate (i.e marginal product falls), provided there is no change in agriculture technology.”

In fact, you can get to a point beyond diminishing returns and start experiencing negative returns. The following table should give and idea of how this happens:

You get each marginal production in tonnes like this: Take row 2 for example. You get a marginal production of 70 by subtracting from its corresponding total production (120), the previous total production (50), 120 – 50 = 70. By the time you get to row 6 you can see that even though you are adding more resources (Labour & Capital), the total production in tonnes drops from what it was previously in row 5.

From all that has been said above, it should be obvious that Africa can’t solve its food production problem by throwing more people at it. “What is to be done?” The answer lies in the definition of the law of diminishing returns given above. The agriculture practiced in Africa is mostly subsistence agriculture. That needs to change to a more commercial model that is highly science and technology driven. That is the reason America’s farmers are so productive. This comes at a price however, and I am not just talking about the expensiveness of science and technology. If we aggressively adopt science and technology into our farming practices the same way America has done, the vast majority of farming labour will become redundant. You can’t have it both ways. You can’t have American agricultural productivity levels without American levels of farming employment. In the event that African agriculture becomes more technology intensive, where are all those people going to go? They will most likely join the already seriously problematic informal economy, whose problems I discussed in a previous post, Structural Corruption , or worse go unemployed (the more hardened ones amongst them will swell the ranks of the criminal class), exacerbating an already difficult unemployment problem. The highly paid service jobs tend not to be enough for the university graduates in the labour market, let alone former subsistence farmers migrating from the rural areas to the cities.

The foregoing discussion highlights the importance manufacturing plays in the economic development of any nation. As countries industrialize, factories have been the traditional destination for the surplus labour no longer required on the farms. Again, America is a case in point. In 1790, about 90% of its population was engaged in farming (population at the time was about 3,893,635), this reduced to 49% in 1890 (population: 62,979,766), this further reduced to 2.6% in 1990 (population: 248,709,873) and is now about 1.3% today with a population of about 328,926,114 [3]. This would not have been possible if the U.S was not at the same time transitioning from an agrarian nation to the world’s premier industrial powerhouse. You can learn more about industrialization from my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe . A more general, important point to be made is that manufacturing is not only important to absorb agricultural surplus labour, it is also a critical input to the transition process from poor nation to rich nation. We would do well to move quickly to solve the very serious problems ailing our manufacturing industry. In 2013, Justin Yifu Lin, a former chief economist at the World Bank stated that “China is on the verge of graduating from low skilled manufacturing jobs that will free up nearly 100 million labor-intensive manufacturing jobs, enough to more than quadruple manufacturing employment in low-income countries.” [4]. The likes of Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Bangladesh are very serious about making in-roads into this bonanza. Getting a decent slice of this will go a long way in solving our serious informal economy issues. As people are taken out of the informal economy and move into formal employment, they can now appropriately bear their own share of the tax burden.

There has been the question as to whether manufacturing is still relevant in a service-dominated world. The answer is YES. It is well known that manufacturing has the largest job multiplier effects (what economists call backward and forward linkages to other sectors in the economy). Consider the economic activity in other sectors of the economy stimulated by the automotive industry: Steel, Rubber, Glass, Energy, Transportation & Logistics, Textile for upholstery, Chemicals for body paint, and many other sectors for automotive components, Entertainment (Car Racing) etc. [5]. Manufacturing activity generates a lot of demand for services particularly in trade and transportation [6]. To take a specific example, a study conducted on the UK fashion industry discovered that the value of manufacturing in the total bill to consumers of a fashion item was around 10% only. The remaining 90% is the share of all services that relayed the product to the consumer [7]. Now while the value of manufacturing in the fashion item is just 10%, that 10% is required to bring the remaining 90% of services into existence. Cambridge Don Han Joon Chang points out that no country has become rich solely on the basis of its service sector [8].

For those of you asking, “How about IT?” The progress in IT too, is dependent on manufacturing. The limits of what can be achieved by software are set by what is known as Moore’s law. Moore’s law is named after Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, the computer chip company. He came up with it in 1965. It states that the density of transistors that can be etched onto integrated circuits, which determines its speed, doubles roughly every 18 months. An integrated circuit (IC) is a chip that houses billions of transistors. The microprocessor in your computer is an example of an IC. A transistor is a device used to amplify or switch electronic signals and electrical power made from semi-conductor material. Semi-conductors are materials that are half-way between conductors and insulators. They allow electric current to pass through them much more easily in one direction than they do in another direction. Progress in semi-conductor manufacturing techniques has played a key part in ensuring the reliability of Moore’s law. While there are some who believe Moore’s law is no longer valid or nearing its end, even in a post Moore’s law world, computer hardware will still place limits on what software can achieve and so manufacturing techniques that produce efficient hardware will remain critical.

I have written this article because the importance of manufacturing seems to be lost on a lot of people, particularly in our part of the world. I hope it will galvanize us into giving manufacturing the attention it sorely deserves.

References

1. Banerjee, Abhijit Duflo, Esther 2019 Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems. UK Penguin Random House

2. Naeem Javid Muhammad. May 2018 ‘Define law of Diminishing Returns and its application to Agriculture and Forestry’ forestypedia.com: https://forestrypedia.com/define-law-...

3. Ross, Sean. Updated Jun 2019 ‘What Impact does Industrialization have on wages?’ investopedia.com: https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answ...

4. The Industrial Policy Revolution II: Africa in the Twenty-first Century, Springer, 2013

5. Yulek Murat 2018 How Nations Succeed: Manufacturing, Trade, Industrial Policy & Economic Development. Singapore Palmgrave Macmillan

6. Roser, Christoph 2017 “Faster, Better, Cheaper” in the History of Manufacturing: From the Stone Age to Lean Manufacturing and Beyond. Boca Raton, Florida CRC Press

7. British Fashion Council. (2010). ‘The value of the UK fashion industry’. London: British Fashion Council. Retrieved from: http://www.britishfashioncouncil.com/... (Accessed 12 June 2015).

8. Chang, Ha-Joon. 2008 Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations & The Threat to Global Prosperity. London: Random House

A decent economist would probably not be surprised this. Economists have long known that the ‘Law of Diminishing Returns’ applies much more strongly to agriculture than to other major areas of economic activity like manufacturing and services [2]. Alfred Marshall, one of the founders of neoclassical economics, defined the law of diminishing returns as applied to agriculture, as follows:

“With each additional input of labour and capital applied to a given piece of land, total product increases at a diminishing rate (i.e marginal product falls), provided there is no change in agriculture technology.”

In fact, you can get to a point beyond diminishing returns and start experiencing negative returns. The following table should give and idea of how this happens:

You get each marginal production in tonnes like this: Take row 2 for example. You get a marginal production of 70 by subtracting from its corresponding total production (120), the previous total production (50), 120 – 50 = 70. By the time you get to row 6 you can see that even though you are adding more resources (Labour & Capital), the total production in tonnes drops from what it was previously in row 5.

From all that has been said above, it should be obvious that Africa can’t solve its food production problem by throwing more people at it. “What is to be done?” The answer lies in the definition of the law of diminishing returns given above. The agriculture practiced in Africa is mostly subsistence agriculture. That needs to change to a more commercial model that is highly science and technology driven. That is the reason America’s farmers are so productive. This comes at a price however, and I am not just talking about the expensiveness of science and technology. If we aggressively adopt science and technology into our farming practices the same way America has done, the vast majority of farming labour will become redundant. You can’t have it both ways. You can’t have American agricultural productivity levels without American levels of farming employment. In the event that African agriculture becomes more technology intensive, where are all those people going to go? They will most likely join the already seriously problematic informal economy, whose problems I discussed in a previous post, Structural Corruption , or worse go unemployed (the more hardened ones amongst them will swell the ranks of the criminal class), exacerbating an already difficult unemployment problem. The highly paid service jobs tend not to be enough for the university graduates in the labour market, let alone former subsistence farmers migrating from the rural areas to the cities.

The foregoing discussion highlights the importance manufacturing plays in the economic development of any nation. As countries industrialize, factories have been the traditional destination for the surplus labour no longer required on the farms. Again, America is a case in point. In 1790, about 90% of its population was engaged in farming (population at the time was about 3,893,635), this reduced to 49% in 1890 (population: 62,979,766), this further reduced to 2.6% in 1990 (population: 248,709,873) and is now about 1.3% today with a population of about 328,926,114 [3]. This would not have been possible if the U.S was not at the same time transitioning from an agrarian nation to the world’s premier industrial powerhouse. You can learn more about industrialization from my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe . A more general, important point to be made is that manufacturing is not only important to absorb agricultural surplus labour, it is also a critical input to the transition process from poor nation to rich nation. We would do well to move quickly to solve the very serious problems ailing our manufacturing industry. In 2013, Justin Yifu Lin, a former chief economist at the World Bank stated that “China is on the verge of graduating from low skilled manufacturing jobs that will free up nearly 100 million labor-intensive manufacturing jobs, enough to more than quadruple manufacturing employment in low-income countries.” [4]. The likes of Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Bangladesh are very serious about making in-roads into this bonanza. Getting a decent slice of this will go a long way in solving our serious informal economy issues. As people are taken out of the informal economy and move into formal employment, they can now appropriately bear their own share of the tax burden.

There has been the question as to whether manufacturing is still relevant in a service-dominated world. The answer is YES. It is well known that manufacturing has the largest job multiplier effects (what economists call backward and forward linkages to other sectors in the economy). Consider the economic activity in other sectors of the economy stimulated by the automotive industry: Steel, Rubber, Glass, Energy, Transportation & Logistics, Textile for upholstery, Chemicals for body paint, and many other sectors for automotive components, Entertainment (Car Racing) etc. [5]. Manufacturing activity generates a lot of demand for services particularly in trade and transportation [6]. To take a specific example, a study conducted on the UK fashion industry discovered that the value of manufacturing in the total bill to consumers of a fashion item was around 10% only. The remaining 90% is the share of all services that relayed the product to the consumer [7]. Now while the value of manufacturing in the fashion item is just 10%, that 10% is required to bring the remaining 90% of services into existence. Cambridge Don Han Joon Chang points out that no country has become rich solely on the basis of its service sector [8].

For those of you asking, “How about IT?” The progress in IT too, is dependent on manufacturing. The limits of what can be achieved by software are set by what is known as Moore’s law. Moore’s law is named after Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, the computer chip company. He came up with it in 1965. It states that the density of transistors that can be etched onto integrated circuits, which determines its speed, doubles roughly every 18 months. An integrated circuit (IC) is a chip that houses billions of transistors. The microprocessor in your computer is an example of an IC. A transistor is a device used to amplify or switch electronic signals and electrical power made from semi-conductor material. Semi-conductors are materials that are half-way between conductors and insulators. They allow electric current to pass through them much more easily in one direction than they do in another direction. Progress in semi-conductor manufacturing techniques has played a key part in ensuring the reliability of Moore’s law. While there are some who believe Moore’s law is no longer valid or nearing its end, even in a post Moore’s law world, computer hardware will still place limits on what software can achieve and so manufacturing techniques that produce efficient hardware will remain critical.

I have written this article because the importance of manufacturing seems to be lost on a lot of people, particularly in our part of the world. I hope it will galvanize us into giving manufacturing the attention it sorely deserves.

References