Abdul Rotimi Mohammed's Blog: Enlightment blog, page 3

August 8, 2023

Africa’s Big Bang Theory

Oh…sorry. Wrong picture. I meant the other big bang theory

In my previous post, I had discussed how Africa had independently developed the field of fractal geometry and applied it to all walks of life. I would like to discuss in this, and subsequent posts other areas of African scientific achievement.

One area of science that has particularly broad appeal beyond scientists themselves is the subject of cosmogony. Cosmogony deals with theories of how the world began or more accurately, how the universe began. Unsurprisingly, many human groups the world over have their pet theories of how the world/universe began, usually in the form of creation myths. One that I find particularly impressive emanated from the African Kingdom of Kongo.

The Kingdom of Kongo was founded around the 13th/14th century and which by the 15th century, was a centralized and well-organized kingdom [1]. The kingdom was modeled not on hereditary succession as was common in Europe, but based on an election by the court nobles from the Kongo people. This required the king to win his legitimacy by a process of recognizing his peers, consensus building as well as regalia and religious ritualism [2]. In other words, the kingdom of Kongo practiced a system of government closer to modern forms of democracy than what typically obtained in Europe at the time.

During the “Scramble for Africa” in the late 19th century just prior to colonization, the French, Belgians and Portuguese divided Kongo among themselves. The French part became what is today called the Republic of Congo and parts of Gabon, the Belgian part became the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) and the Portuguese part became parts of Angola.

Kongo Cosmogony bears a striking resemblance to the “Big Bang Theory”, the reigning cosmological model of how the universe began that is generally accepted by scientists. It almost certainly was developed independently, as evidence exists of Kongo’s cosmological beliefs having existed before European contact in 1482 [3], whereas the observation leading to the Big Bang Theory was only first made in 1929 by American astronomer Edwin Hubble. The people of Kongo (called the Bakongo) believed that in the beginning, there was only a circular void of nothingness, called mbûngi. Then the creator god Nzambi Mpungu summoned a spark of fire, or Kalûnga, that grew until it filled the mbûngi [4]. The Big Bang Theory states that the universe expanded from an initial state of high density (in essence of all matter condensed into a tiny point, where the concept of space has no meaning) and temperature. The heated force of the Kalûnga produced a storm of projectiles, kimbwadende, which when cooled, fused and solidified to form the earth and other heavenly bodies [5]. The Big Bang Theory states that after the universe’s initial expansion it cooled sufficiently to allow the formation of sub-atomic particles and later atoms, which then later coalesced through gravity, forming early stars and galaxies.

Kongo Cosmogony makes accommodation for stages in the evolution of the universe that a scientist would appreciate. According to the Kongo, planets go through four stages of evolution. The first stage is the emergence of the fire. The second stage is the red stage, where the planet is still burning and is without clearly defined shape or form. The third stage, the grey stage, the planets are in the process of cooling and so cannot support life yet. The final stage, the green stage, the planet breathes and is able to support life [6]. Kongo Cosmogony is even sophisticated enough to make room for the possibility of aliens in outer space, or at least the possibility of man inhabiting other planets other than earth [7]. I personally find the parallels simply remarkable.

It is possible that you might be asking, why is the Big Bang Theory is the gold standard anyway? To answer that a little history lesson might be in order. In 1929, Edwin Hubble, observing the universe through large telescopes located at the astronomy observatory where he worked, made a startling discovery. In every direction you looked, the universe was receding further and further away. If you are having trouble visualizing this, imagine a white deflated balloon. Now let’s assume that we have used a black pen to mark the deflated balloon with lots of black spots. As you inflate the balloon, you will notice that each black spot is moving away from every other black spot as the balloon expands. So the first point scored by the Big Bang Theory is that, it isn’t just a clever argument. If you have a powerful enough telescope and know what to look for, you can see this expansion for yourself.

Now by logical reasoning, it was inferred that if every region of the universe is moving away from every other region, all those regions must have been closer to each other at an earlier point in time. To take the inference to its logical conclusion, every part of the universe must have at one time been collapsed together in a single point. That point being the “Big Bang”, the moment of the universe’s creation. Interestingly, the label “Big Bang” was originally meant as an insult by a skeptic but as is often the case, proponents of the Big Bang Theory eventually adopted it as a badge of honor.

Now simply having a reasonable argument even though driven by observation isn’t enough. So in the 1948, a cosmologist by the name of George Gamow, based on work done by his PhD students proposed that if the Big Bang really did happen, then in the outermost regions of the universe, there should exist what is referred to as the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. This is essentially the remnants of the Big Bang explosion, kind of like the fragments left behind when you detonate a bomb or launch a grenade. He didn’t stop there. He went on to describe the exact characteristics that this background radiation should have. He had to wait almost 20 years for confirmation.

In 1965, two radio astronomers working at Bell Labs, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson who were carrying out research totally unrelated to the Big Bang Theory, detected a very faint radio noise that was uniform, in the sense that, in every direction they pointed their equipment, they could detect it. After eliminating every possible source of interference, including bird and bat droppings that Penzias described as “white dielectric material” in a report, it was suggested to them that they might have just discovered the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. This was eventually confirmed to be true. It was also discovered that it had the characteristics almost exactly like how George Gamow predicted. Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson would be awarded the Nobel Prize in 1978. You have to discover on your own why neither Gamow, nor any of his students shared in the prize. Even the person who suggested to them that they might have hit the jackpot, didn’t share in the prize.

The Bakongo, in my opinion had come up with a remarkable hypothesis even from the vantage point of the 20th century, but if you want global recognition, you have to make global impact. Not that I am suggesting that global impact was the goal of the Bakongo. This is highly unlikely to be the case as in all likelihood, their cosmogony was developed centuries ago, prior to contact with Europeans. Also, because their cosmogony was bound up with their spirituality unlike the Big Bang Theory which is purely secular, they probably didn’t see much need of obtaining empirical evidence of their cosmogony beliefs. In any case, the technology to do so simply did not exist anywhere in the world at the time.

One more thing I would like to say about the Big Bang Theory. There is this conception that it is anti—religious or anti-God. No it isn’t. The Big Bang Theory neither confirms or denies the existence of God. On the subject of God, it is silent, making it a potential weapon of believers and non-believers alike. In fact, it hasn’t gone unnoticed that the implication of the Big Bang Theory, that the universe had a definite beginning, sounds somewhat similar to Genesis Chapter 1, verse 1. A rival theory called the Steady-State model, that was pushed vigorously by Soviet scientists (but not originated by them) which posited that the universe was eternal, without beginning or end, therefore making no room for the existence of God, had to be abandoned on the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation because without a beginning, there could be no explosion, without an explosion, there could be no background radiation. Since there was background radiation, the Steady-State model had to be wrong.

To buttress the point about the Big Bang Theory not being anti-God, on November the 22nd, 1951, at the opening meeting of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Pope Pius XII declared that the Big Bang theory does not conflict with the Catholic concept of creation. In fact, the Big Bang Theory was partly developed by a Catholic priest by the name of Georges Lemaître [8]. Mirza Tahir Ahmad, a former head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim community, asserted in his book Revelation, Rationality, Knowledge & Truth that the Big Bang theory was foretold in the Quran [9]. Faheem Ashraf of the Islamic Research Foundation International, Inc. and Sheikh Omar Suleiman of the Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research argue that the scientific theory of an expanding universe is described in Sūrat adh-Dhāriyāt (The 51st chapter of the Quran) [10].

I think it is important that people understand properly what they are opposing before they oppose it. We will explore more of Africa’s scientific history in subsequent posts.

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this post with as many people and check out my book Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe on Amazon.

References:

1. Wikipedia article on Kongo https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kongo_p...

2. Ibid

3. Wikipedia article on Kongo cosmogram https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kongo_c...

4. Kimbwadende Kia Bunsenki Fu-Kiau. 1980 African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life & Living New York Athelia Henrietta Press

5. Ibid

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. Wikipedia article on Religious Interpretations of the Big Bang Theory https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religio...

9. Ibid

10. Ibid

Published on August 08, 2023 00:06

August 1, 2023

African Fractals: The mathematics of Kente, Adire cloth, and Ipako Elede (Corn Rows) hairstyle explained

Michelle Obama pictured wearing Adire

A recurrent theme throughout my blog posts is the need for Africa to seriously harness science and technology for economic development and for Africans to embrace scientific thinking and develop a rational worldview. Given where we currently are this might seem like a tall order, but we should not despair. The capacity for rational thinking and scientific reasoning is one that all humans are endowed with. It should give us much encouragement to know that such capacity has been exhibited by Africans in times past (and present) and some evidence of this still exists in even some common objects around us.

Perhaps no field of scientific endeavor showcases the traditional African’s capacity for science than that of Fractal Geometry. Fractal Geometry is that branch of geometry that deals with the shape of many natural objects, as opposed to Euclidean Geometry (the one you learnt in secondary school) which deals with ideal shapes like circles, triangles, rectangles etc. that are surprisingly rare in nature (This should not be interpreted as a critique of Euclidean Geometry or that it is inferior. Both systems have their strengths and weaknesses). Think about it...how many things do you know in nature that are perfect circles, squares, triangles etc.? (Though critics would point to eggs, which are perfectly oval). Examples of things in nature that are considered fractals include algae, blood vessels, clouds, coastlines, crystals, DNA, earthquakes, heartbeat patterns, lightning bolts, mountain ranges, ocean waves, proteins, snowflakes, trees, etc. What all these things have in common is that if you look at a small part of the object, that small part looks like a small-scale version of the bigger object that it is a part of. Take the tree for example. If you look at a branch, it looks like a smaller version of the entire tree. Contrast that with a car, there isn’t any part of the car that looks like a small-scale replica of the entire car. Mathematicians refer to this repetition of patterns as self-similarity, and the change in size of the similarly shaped patterns, is referred to as scaling. Fractal analysis can be applied in a mind-numbing number of fields, from electronics engineering, to thermodynamics, biochemistry, video game design, finance, economics, fashion, medicine, neuroscience, geology, geography, archaeology etc.

Fractal geometry is also intricately bound up with branch of mathematics/science known as “Chaos Theory”. Chaos Theory studies systems that are extremely sensitive to their starting conditions. Changing those starting conditions ever so slightly can lead to changes so drastic in the overall system that the system could end up being radically different from what it was in the beginning, making long term prediction of such systems’ behaviour impossible. The classic examples of chaotic systems are the weather and the stock market. This is why weather predictions are good for at best a few days ahead. Many academics in economics and finance claim that the stock market cannot even be predicted at all and that those that have seemingly made repeated killings in the market like Warren Buffet and George Soros are simply lucky monkeys. If you want to know more about this debate you can read up on the “Efficient Markets Hypothesis”. Chaotic systems make their appearance in many more areas of science and engineering. Often, in order to understand them better, scientists/engineers would often like a pictorial representation of a chaotic system. To do that, they program the mathematical equations that govern the behavior of chaotic systems into computers to generate graphics. The imagery generated is often stunningly beautiful, like this one:

Or this:

As noted, many naturally occurring objects tend to be fractals. As a result, the movie and videogame industries have tapped into fractal geometry to give “special effects” a touch of realism. An example would be this scene from one of the Guardians of the Galaxy movies:

Or this videogame scene rendered by the legendary Unreal game engine:

The word,” fractal” was only coined recently, in 1975 by a French mathematician by the name of Benoit Mandelbrot. As a field of study, fractal geometry only took off in the west in the 17th century [1]. Africans, however have been doing fractal geometry long before then. Indigenous African architecture makes use of fractal design heavily. One example that probably stands out is the Great Wall of Benin (In Nigeria), destroyed by the British in 1897. It was estimated to be about 16,000km long. The only man-made artifact longer than that is the Great Wall of China, which is about 21,000km [2]. It took about 600 years for the people of Benin to complete it. Construction of the wall started out in the year 800 and wasn’t completed until around the year 1460 [3]. The walls guarded the city of Benin which, according to Portuguese visitors that visited in 1485, “was one of the most beautiful and best planned cities in the world” [4]. The design of the city and surrounding villages was based on fractal geometry. The use of fractal geometry in indigenous architecture abound across Africa. Other examples for instance, can be found in the indigenous settlements of the Kotoko people of the city of Logone-Birni in Cameroun, the Baila settlements in Southern Zimbabwe, and in the famous stone buildings of the Mandara Mountains in Cameroun [5].

Indigenes of the Sahel in Africa build windscreens to keep out strong wind and dust, utilizing fractal scaling patterns such that from bottom to the top of the windscreen, similar sections of straw of decreasing length are used to build the windscreen. The choices of the lengths of the different sections are not arbitrary. They show that the windscreen makers understand the mathematical relationship between wind speed and height (Of course, when I say this, I am not implying that they sit down and solve one equation like that, like you would in class. What I am saying is that mentally speaking, they have a decent mathematical model in their heads). Western mathematicians who have studied these windscreens have found that they closely fit what are known as power laws [6]. A power law is a mathematical relationship between two variables such that a change in one variable leads to a large change in the other variable because the change in the other variable is raised to a power (Like 2 raised to power 4, which equals 16. If 2 is changed to 3, 3 raised to power 4 becomes 81, a big jump from 16). The S-curve of technology adoption that I discussed in a previous post, is an example of a power law. The most common equations found in Wind Engineering Handbooks used by western engineers also happen to be power laws [7]. This shows that the windscreen makers in the Sahel clearly know what they are doing. Though the Sahel technique and western engineering give different answers, for instance, the value of a certain parameter derived by the Sahel technique was found to be roughly 3 times the value given by the western wind engineering handbooks, it was nonetheless judged to be a decent rough approximation by the western mathematicians studying the Sahel windscreens [8].

Another notable area where there is a preponderance of fractals is in African textiles. In Ghana, older kente patterns of the kind produced by handlooms in the village, and not the newer ones produced by automated machines that are exported, make use of a scaling technique that actually has an equivalent in western mathematics (For the mathematically inclined, the western mathematical method is called contractive affine transformation) [9]. Again, like the Sahel windscreen makers, the kente cloth makers do not apply the scaling technique by solving equations on paper or programming the equations into computers as westerners do. They use it by having a roughly right mental model in their heads and applying it to kente cloth design. Adire cloth makers from Nigeria aren’t left out. They also have a scaling algorithm (An algorithm is a mathematical procedure for solving a problem). Western mathematicians who have studied it have found it to be rather efficient [10].

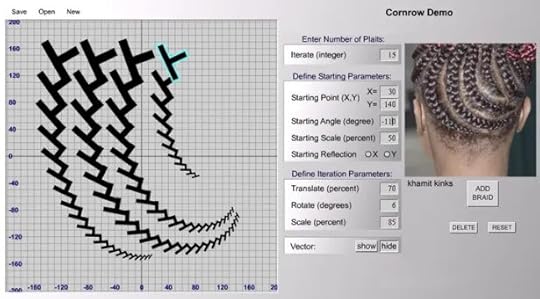

Yet another application of fractal geometry which I was pleasantly surprised to discover was that African women hair plaiting styles. A lot of them are examples of what in the subject of geometry would be referred to as conformal mapping. In conformal mapping, a pattern is made to fit along the contours of a pre-existing structure…um...um…the structure in this case being the woman’s head. An example of this would be the Yoruba hairstyle called “Ipako Elede” (This translates to the nape of the neck of a pig. The pig’s bristles are known to have a similar scaling pattern). Americans call this hairstyle corn-rows and it is frequently sported by both male and female African-American hip-hop and NBA basketball stars. The mathematical structure of the Ipako Elede/Corn rows hairstyle might be better appreciated by looking at the screenshot of a piece of geometrical modeling software below:

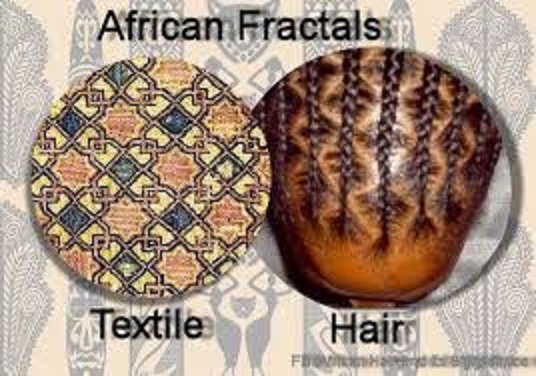

The fractal property of self-similarity (repeating pattern) is pretty self-evident from the picture of the girl’s head. The scaling property (changing size of the repeating pattern) might not be so evident, but it is well-known among African women that with certain styles, the braid starts small and then gets progressively bigger, with each added plait. I think you can see that in at least one braid, the one that gets closest to her left ear. The repetitive nature of fractal patterns makes them a natural candidate to be artificially generated by computer programming. What you are seeing in the left side of the screenshot are Computer Generated Images (CGI) of the Ipako Elede braids. And because the braids consist of repeating plaits, all you have to do is specify the mathematical properties of the starting plait, the rules (algorithm) for generating the next plait from the preceding plait and the number of times the process is to be repeated (In computer programming this is called iteration) to be able to generate an entire braid from the starting plait. Like I intimated earlier, Ipako Elede is just one of many African hairstyles that exhibit fractal patterns. Others include Koroba, another Yoruba hairstyle and la tresse de fil, a hairstyle from Yaoundé, Cameroun. Perhaps looking at textiles and hairstyles (pun unintended) side by side would give you a better appreciation of the wide applications of fractal geometry:

It has been asked, particularly by westerners whether in African fractal design, there has been a deliberate attempt to grasp at underlying mathematical/scientific principles, indispensable for labelling anything as science or whether the designs are merely intuitive, with no attempt at understanding underlying order and simply made to have aesthetic appeal. Studies have concluded that African fractal designs occupy a large spectrum running from designs that are merely intuitive, to ones where like the windscreen example, there is a clear attempt to gain understanding of underlying scientific principles [11].

In future posts we will explore more African scientific and technological exploits. As a parting shot, I leave you with a fractal image of Africa:

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this post with as many people as possible and please check out my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe on Amazon. Thank you

References:

1. Fractal Article on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fractal

2. Website about the Great Benin Wall: https://www.kingdomofbenin.com/the-be...

3. Ibid

4. Koutonin, Mawuna. Mar 2016 ‘Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace’ theguardian.com: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/20...

5. Eglash, Ron. 1999 African Fractals: Modern Computing And Indigenous Design New Brunswick Rutgers University Press

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. Ibid

9. Ibid

10. Ibid

11. ibid

Published on August 01, 2023 23:35

July 4, 2023

Shango, Amadioha, Thor…are we really that different from white people?

This post is a reproduction of a WhatsApp chat I had with an On Air Personality (OAP). He has given me permission to quote him verbatim.

Good evening Tony (Not real name). I was introduced to you yesterday by Gabriel (Not real name). My name is Abdul (Real name). I really enjoyed the conversation we were having yesterday. I wish we could have completed it. I just want to recap on some things I said and respond to the things you said…

I had mentioned that I had a difference of opinion with Walter Rodney (Author of How Europe underdeveloped Africa). I do not believe the exploitation of Africa, criminal though it was, is the main factor for the mass prosperity that Europe started to have in the 18th century. It certainly helped but it wasn’t the main thing. The main thing was the aggressive development of science and technology and the development of political, legal, economic and social institutions that enabled western society to derive the maximum benefits from their investment in science and technology. The resources they criminally got from us was just an input into this vast industrial complex. Without the input of African resources, they would have still gotten to their wealthy destination though it might have taken a longer time and I will prove it….

The East Asians, particularly Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan have managed to become just as rich as the west even though they did not copy the west’s plunder and rape of other continents. What they did copy from the west was the aggressive development of science and technology and the institutions required to obtain maximum benefit from the scientific investments made.

Which now brings me to the point you made about some academics positing that the reasons the Asians succeeded was their retention of their traditional religions. I do not accept this hypothesis. As stated above, the reason for Asian success was the aggressive development of science and technology and the accompanying institutions and I will prove this with the example of Europe. Christianity wasn’t the traditional religion of Europe. They originally believed in various small gods like us Africans. A well-known example as the result of the Marvel movies is the Old English/German/Scandinavian/Norse god called Thor, who is the god of thunder like our Shango or Amadioha. In fact, 4 days in the week are named after old English gods. Thursday is named after Thor (Thor’s day). Wednesday is named after his father, Odin (Odin is the Scandinavian/Norse version of the name). Odin in old English is Woden and Wednesday is Woden’s day. Friday is named after Odin’s wife (but not Thor’s mother) Frigg and Tuesday is named after an old English god called either Tiw or Tyr. The remaining days are obviously named after heavenly bodies. Heavenly bodies in ancient times have often been worshipped as gods. Swapping out their traditional religions for Christianity didn’t stop the west from developing the science and technology that made them wealthy, neither should it stop us.

By the way, Islam is not even the traditional religion of the Arabs. Like Africans and Europeans, the Arabs believed in a variety of small gods until the Prophet Muhammad introduced them to Allah and Islam.

You mentioned Karl Marx’ quote about ‘Religion being the opiate of the masses’ and what we can do to change this. My answer would be the Enlightenment. I briefly describe the Enlightenment in this post of mine. Briefly, the Enlightenment forms the intellectual foundation of western society. It provides the foundational values of the western institutions we have tried to copy in Africa in the hope of emulating western material success. These values are scientific in outlook and they are reason, skepticism and individualism. Not individualism in the sense of being selfish, but in the sense of there being respect for the individual and recognizing individual rights. You would agree with me that this value system has hardly penetrated the African psyche. Contemporary African values are more based on faith, tradition and group orientation. So the way I see it, there is a fundamental clash between the current African value system and the institutions we have borrowed in the hope of solving our problems. The question now is how do we resolve the conflict?

Which brings me to the last comment you made about the difference in culture but we didn’t have time to discuss it. Given the way I have laid out the central conflict of contemporary African society, you might be tempted to conclude those academics were right about our need to return to traditional African culture. Forgive me for sounding ignorant but what exactly is traditional African culture? African culture is one of those terms constantly thrown around and everybody assumes they know what it means but there is little critical examination of what it really means. Is African culture having many children? Europeans did exactly the same thing 200-300 years ago for the exact same reasons Africa’s poor have large families today. They were locked out of regular jobs and so didn’t have access to a regular salary and pensions and a significant number of their children succumbed to disease. They needed many children to provide labour on the family farm and as pension/insurance when they were old and could no longer work. Is it respect for elders? East Asians are also big on that. Is it tribalism? Just as we have Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba, the English at one time had the Jutes, Celts (The names of Scottish football club, Celtic and NBA franchise, Boston Celtic are derived from this tribe), Angles (This tribe eventually gave its name to the whole of England. England means “Land of Angles”) and Saxons (If you watched Robin Hood when you were small or Robin Hood associated TV series like Ivanhoe and you were paying attention, there is a good chance that you might have heard about this tribe. Robin Hood is often portrayed as being a Saxon. By the way, Game of Thrones is partly based on Ivanhoe. Robin Hood’s battles with his chief antagonists of The Sheriff of Nottingham and Sir Guy of Gisborne can be cast in the terms of inter-tribal conflict as his antagonists were Normans, who were a group that migrated from France and captured the English crown and placed the Saxons under their yoke of oppression). Just like the British forced us into one nation, The Romans forced the various English tribes into one nation around the time of Jesus Christ. When the Roman Empire fell 400-500 years later, these English tribes scattered. It took them about 600 years to develop the political maturity required of them to come together of their own volition as one nation. The Prophet Muhammad had much trouble unifying the quarreling tribes of first, Medina and then those of Mecca and then ultimately unifying them into a nation-state. His teachings were in a certain sense deliberately anti-tribal, in that his teachings proclaimed the existence of a universal umma or community of believers whose first loyalty was to God and God’s word and not to their tribe. China has been struggling with tribalism for like 2,000 years even though 92% of the people come from one tribe, the Han tribe. The Uighurs in China are a group that suffers severe discrimination to the point that even former Real Madrid baller, Mesut Ozil (I hate Arsenal. GGMU…if you know, you know) talked about it.

I have mentioned all these to elucidate two general points. 1. Culture is not static. It is always changing, as culture is significantly a response to one’s environment, which is always changing. 2. What we consider the specific culture of one group is actually more generic and is more of a human trait. It is just that different parts of the world are at different stages of development so they exhibit different traits at any specific point in time but all of mankind is capable of exhibiting those traits.

So in response to your echoing Karl Marx, I believe the average African needs to become more rational, more scientific in his/her worldview, in his/her outlook and approach to life in general. This takes time and it also takes education. This is why I take the time to write in general and the reason I have written this long monologue to you. Sorry 4 not letting u get in a word edgewise (Laughing emoji).

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this post with as many people as possible and check out my book Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe. Thanks

Published on July 04, 2023 23:25

June 28, 2023

Public vs Private Healthcare in low and middle income countries

This is a continuation of my last post. In that post, I tried to show in general just how complicated the public vs private debate could get. In this post, I use the healthcare sector to illustrate the nuances of the private vs public debate.

Generally, this debate has been divided between those seeking universal state-based healthcare availability and those advocating for the private sector to provide care in areas where the public sector has typically failed. Private sector advocates have pointed to evidence that the “private sector is the main provider,” as many impoverished patients prefer to seek care at private clinics. They have suggested that the private sector may be more efficient and responsive to patient needs because of market competition, which they indicate should overcome government inefficiency and corruption. In contrast, public sector advocates have highlighted inequities in access to health care resulting from the inability of the poor to pay for private services. They have noted that private markets often fail to deliver public health goods including preventative services (a “market failure”), and lack coordinated planning with public health systems, required to curb epidemics.

This post highlights the major insights gleaned from a systematic review of comparative performance of private and public healthcare systems in low and middle-income countries conducted by researchers based at western academic and health institutions. It is important to point out that studies comparing the performance of private and public sectors are difficult to implement, for several reasons. Healthcare services are not universally dichotomized between public and private providers, as some practitioners participate in both state-based and privately owned healthcare delivery systems, and many systems are dually funded or informal.

The healthcare systems were evaluated using WHO criteria of:

• accessibility and responsiveness

• quality

• outcomes

• accountability, transparency, and regulation

• fairness and equity

• efficiency

Out of the 102 relevant studies included in their comparative analysis, one-third of studies were conducted in Africa and a third in Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Philippines, Cambodia, Myanmar, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Singapore, Vietnam).

This systematic review did not support previous views that private sector delivery of health care in low- and middle-income settings is more efficient, accountable, or effective than public sector delivery; however, the public sector appears frequently to lack timeliness and hospitality towards patients. Each system has its strengths and weaknesses, but importantly, in both sectors, there were financial barriers to care, and each had poor accountability and transparency. This systematic review highlights a limited and poor-quality evidence base regarding the comparative performance of the two systems. Private sector healthcare systems tended to lack published data by which to evaluate their performance, had greater risks of low-quality care, and served higher socio-economic groups, whereas the public sector tended to be less responsive to patients and lacked availability of supplies. Contrary to prevailing assumptions, the private sector appeared to have lower efficiency than the public sector, resulting from higher drug costs, perverse incentives for unnecessary testing and treatment, greater risks of complications, and weak regulation. Both public and private sector systems had poor accountability and transparency. Within all WHO health system themes, study findings varied considerably across countries and by the methods employed.

Comparative cohort and cross-sectional studies suggested that providers in the private sector more frequently violated medical standards of practice and had poorer patient outcomes, but had greater reported timeliness and hospitality to patients.

Public sector services experienced more limited availability of equipment, medications, and trained healthcare workers.

When the definition of “private sector” included unlicensed and uncertified providers such as drug shop owners, most patients appeared to access care in the private sector; however, when unlicensed healthcare providers were excluded from the analysis, the majority of people accessed public sector care. However, there were three exceptions: Namibia, Tanzania, and Zambia, where private sectors are majority providers even when only licensed personnel are counted.

Financial barriers to care, such as user fees were reported for both public and private systems. User fees are health payments charged at the point of accessing health care services.

The analysis found that private outpatient clinics often had better drug supplies and responsiveness than public clinics.

Women living in rural Nigeria also reported preferring private obstetric services to public services because doctors were more frequently present at the time of patient presentation.

In Nigeria, public providers were significantly more likely to use rapid malaria diagnostics and to use the recommended combination therapies than private providers.

Poor adherence to guidelines in prescription practices, including sub-therapeutic dosing, by private sector providers has been associated with a rise in drug-resistant malaria in Nigeria. Failure to provide oral rehydration salts, and prescribing of unnecessary antibiotics were more likely to occur among private than public providers although there were exceptions.

Higher rates of potentially unnecessary procedures, particularly cesarean sections (C-sections), were also reported at private than at public settings.

Reports from Africa and Laos suggest ineffective and sometimes harmful pharmaceuticals are being distributed in the private sector.

Surveys of patients' perceptions of care quality were mixed. Two survey-based studies suggested that patients perceived higher quality among private practitioners, possibly due to frequent prescribing of medications and more time spent with patients.

Public sector provision was associated with higher rates of treatment success for tuberculosis and HIV as well as vaccination. For example, in Pakistan, a matched cohort study in Karachi found that public sector tuberculosis care resulted in an 85% higher treatment success rate than private sector care. In Thailand, patients seeking care in private institutions had significantly lower treatment success rates for tuberculosis, which was attributed to a three to five times greater likelihood of being prescribed non-WHO-recommended regimens than in the public sector. In South Korea, tuberculosis treatment success rates were 51.8% in private clinics as opposed to 79.7% in public clinics, with only 26.2% of patients in private clinics receiving the recommended therapy, and over 40% receiving an inappropriately short duration of therapy. Similarly higher rates of treatment failure were observed for private than public system patients on antiretroviral therapy for HIV in Botswana. In India, an analysis of over 120,000 households, adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic factors, found that children receiving private health services were less likely to receive measles vaccinations. Similar findings were reported from Cambodia.

Studies comparing pre- and post-privatization outcomes tended to find worse health system performance associated with rapid and extensive healthcare privatization initiatives in Latin American countries. However, a slower pace of privatization of health care services did not appear to correlate with a substantial worsening in patient outcomes among Latin American countries.

On Accountability, Transparency, and Regulation, data tended to be unavailable from the private sector. No papers were found to describe any systematic collection of outcome data from entirely private sector sources. One recent independent review of Ghana's private sector referred to the private sector as a “black box,” with a dearth of information on delivery practices and outcomes. Tuberculosis and malaria case notification to the public health system was particularly poor among private sector providers as compared to public providers in a number of countries.

Several reports observed significant public spending being used to regulate the private sector in order to improve patient care quality, particularly in African countries, and with limited effectiveness.

Financial barriers to care, particularly user fees, were reported to be prevalent in both private and public systems. A World Bank study in Ghana concluded that there was no systematic evidence indicating whether user fees in the public sector were different than in the private sector however, the data presented showed that out-of-pocket user fees for patients were highest for private not-for-profit, lowest for public, and intermediate for private self-financed providers. Hence, the conclusions of the report appear to be disputed by the data within the report.

Several studies suggested that the process of privatizing existing public services increased inequalities in the distribution of services. Analyses of the Tanzanian and Chilean health systems found that privatization led to many clinics being built in areas with less need, whereas prior to privatization government clinics had opened in underserved areas and made greater improvements in expanding population coverage of health services.

Privatization in China was statistically related to a rise in out-of-pocket expenditures, such that by 2001, half of Chinese surveyed reported that they had forgone health care in the previous year due to costs; out-of-pocket expenses accounted for 58% of healthcare spending in 2002 compared with 20% in 1978 when privatization began.

One survey-based study using Demographic Health Survey data from 34 sub-Saharan African countries found that privatization was associated with increased access, and reduced disparities in access between rich and poor.

Several reports observed higher prescription drug costs in the private sector for equivalent clinical diagnoses. Tanzanian private facilities typically used more brand-name oral hypoglycemic agents, but even generic medications were five times higher in price.

There is also evidence that the process of privatization is associated with increased drug costs. A study of the Malaysian health system found that increasing privatization of health services was associated with increased medicine prices and decreased stability of prices.

Healthcare costs in Colombia rose significantly following privatization reform in 1993. It was estimated that in Mexico, Brazil, and South Africa, unnecessary C-sections increased delivery-related health costs in the private sector by at least 10-fold.

Several studies found that poor reporting of diseases in the private sector impeded public sector control of communicable diseases.

The review showed that some findings in low- and middle-income countries mirrored existing evidence from high-income countries. For example, the lack of data from private sector groups was similar to the situation in the UK, where the privately run Independent Sector Treatment Centres were unable to provide healthcare performance data when required. However, the evidence also indicates that contextual factors modify the relationships we have observed, so that it is not straightforward to transpose health system evidence from high-income countries to low- and middle-income countries. Importantly, we observed that regulatory conditions interact with the effectiveness of public and private sector provision, but in low- and middle-income countries regulatory capacity is much weaker.

Overall, the data describing the performance of public and private systems remains highly limited and poor in quality, suggesting that further investigations should more systematically make data available to track the performance of both public and private care systems before further judgments are made concerning their relative merits and risks.

This study was published in 2012 by researchers from the following institutions:

• Department of Medicine, University of California (San Francisco), USA

• Division of General Internal Medicine, San Francisco General Hospital, USA

• Department of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK

• Division of Infectious Diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, USA

• Tri-Institutional MD-PhD Program, Weill Cornell Medical College/Rockefeller University/Sloan-Kettering Institute, USA

• Division of Global Health Equity, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, USA

• Department of Sociology, Cambridge University, UK

The period covered in the study is from 1 January 1980 to 31 August 2011.

BEFORE YOU GO: Please share this post with as many people as possible and please check out my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe on Amazon. Thank you

Bibliography

1. Basu, Sanjay et al. June 2012 ‘Comparative Performance of Private and Public Healthcare Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review’ PLoS Medicine

Published on June 28, 2023 00:36

June 20, 2023

The Private Sector’s Case Against Government Involvement in Economic Activity…and the Appropriate Responses

This is a continuation of my last post, which was a verbatim reproduction of a private conversation with an investment banker.

This topic about government’s proper role in the workings of society is a critical one that has been taking place the world over for at least a few centuries now. The popularity of the view you hold has been responsible for the waves of privatization in recent decades. Free marketers often make it seem like it is the only logical choice but sober reflection from others suggests a more complicated picture. I would like to highlight some insights that have come out from this more nuanced discussion about the privatization of State Owned Enterprises (SOEs).

Much of the free marketers’ case against SOEs (And I admit that there is a lot of truth in it) is what is known in the economic literature as the principal-agent problem. Here the principals being the citizenry have elected bureaucrats (the agents) to manage SOEs in the principals’ best interest but the problem is linking the pay of public bureaucrats to the profitability of SOEs, is an incentive system that is notoriously difficult to design. Moreover, individual citizens are not incentivized to monitor the SOEs because the costs will be borne by them alone while the benefits will be shared by everybody (This is known as the free-rider problem). An associated problem is the soft-budget constraint problem: Being a part of the government, the argument goes, SOEs are often able to secure additional finances from the government if they make losses or are threatened with bankruptcy, which could lead to lax management.

Now it has been noticed that despite the threat of market discipline, these problems occur as well in large private sector companies to a significant extent.

Most large private sector companies are managed by hired managers because they have dispersed share ownership. If a private enterprise is run by hired managers and there are numerous shareholders owning only small fractions of the company, it will suffer from the same problems as state-owned enterprises. The hired managers (like their SOE counterparts) will also have no incentive to put in more than sub-optimal levels of effort (the principal-agent problem), while individual shareholders will not have enough incentive to monitor the hired managers just like with SOEs (the free-rider problem).

In addition, politically important, large private companies often get bail-outs from government (e.g in Nigeria, banks, electricity gencos/discos. Global examples include defense contractors, large companies in the finance, automotive and aerospace industries). In other words, there is the private company version of the soft budget constraint problem. To take the example of Nigerian banks, CBN is reputed to have spent over N3 trillion in 8 years between 2009 and 2017, in the wake of the Global Financial Crises of 2008 to stabilize the financial sector. Other global examples include Britain nationalizing some key firms in the 60s and 70s. They include Rolls Royce in 1971, British Steel in 1967, British Leyland in 1977, and British Aerospace also in 1977. Greece rescued about 43 bankrupt private sector firms between 1983 and 1987. In the 1980s, the US government under Ronald Reagan rescued carmaker, Chrysler. This one is especially ironic given that along with Margaret Thatcher, Reagan was the hardest pusher for liberalization/deregulation/privatization. In 1982, the Chilean government rescued the entire banking sector. This was another ironic one, in that this was the regime of General Augusto Pinochet, who came to power in 1973 via a bloody coup, in a bid to usher in free market capitalism, and in which the previous president, a Marxist by the name of Salvador Allende, committed suicide by gunshot.

Conversely SOEs are not totally immune to market forces. Many SOEs around the world have been shut down and their managers sacked because of bad performance. For example, during China’s market reform period between 1978 and 2006, lots of new entrepreneurs were allowed to compete against many SOEs and the SOEs that couldn’t compete were allowed to fail.

Furthermore, there are examples of first class SOEs so it is not inevitable that SOEs will be poorly run. Examples include Singapore Airlines, EMBRAER from Brazil, which is the third largest aircraft maker after Boeing and Airbus. Though it is privatized now, it achieved world class status under state ownership. Petrobras, the Brazilian state owned oil company is also world class. Quite a number of French companies that have become household names achieved world class status under government ownership, though now privatized. They include Renault, Alcatel, Elf Aquitaine, Thomson (electronics), Thales (defence electronics), Rhone-Poulenc (now part of pharmaceutical giant Sanofi-Aventis), Ursinor (Now part of Arcelor-Mittal, the largest steelmaker in the world). Locally, I would add NAFDAC under Dora Akunyuli was well run. Elsewhere on the African continent, Namibia is a country whose state enterprises are generally known to be operating at a profit.

Economic theory shows that there are circumstances under which public enterprises are superior to private-sector firms. This happens when a project has clear long-term viability but private capital refuses to get involved because the short term risks are large. An example is the internet described above (In the last post) and this is often the case when spawning new industries that are capital-intensive. A good current example would be the renewable energy industry, an area that China’s government is investing heavily. What these examples show is that SOEs have often been used to kick-start capitalism, not replace it. Resorting to SOEs to kick-start capitalism is an option more frequently used at earlier stages of development where capital markets are not well developed and therefore tend to be conservative.

SOEs can also be ideal when a natural monopoly exists. This refers to a situation where technology conditions dictate that having only one supplier is the most efficient way to serve the market. A good example of this in Nigeria is the Transmission sub-sector of the Power sector. Government retained ownership of Transmission while privatizing Generation and Distribution.

State-owned enterprises are also often a more practical solution than a system of subsidies and regulations for private-sector providers, especially in developing countries that lack tax and regulatory capabilities.

Privatization of natural monopolies or essential services will also fail if they are not subject to the right regulatory regime afterwards. When the SOEs concerned are natural monopolies, privatization without the appropriate regulatory capability on the part of the government may replace inefficient but (politically) restrained public monopolies with inefficient and unrestrained private monopolies.

The 1980s to the early 2000s saw a wave of privatization across Africa and the world at large, the results of which appear to have been mixed. No doubt there have been some stunning successes like the privatization of telecoms by Obasanjo. There have also been terrible failures, like privatization of our paper mills. On the world stage, privatization exercises with less than satisfactory results include the British rail privatization of 1993, in which the rail tracks had to be re-nationalized in 2002; The failed electricity deregulation of the state of California in the USA, which resulted in the infamous blackout of 2001. There is of course Russia, which is the poster child for privatization run amok. In a rushed privatization programme during the mid-90s, a corrupt group of businessmen with ties to the Russian mafia ended up acquiring about $100 billion worth of mainly oil and gas public resources for no more than $1 billion according to best estimates. I don’t want to make this document longer than it is already but there are enough examples on both sides to show that privatization is not a straightforward no-brainer.

Bibliography

1. Chang, Ha-Joon. 2007 Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity UK: Random House

2. Mazzucato, Mariana 2013 The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths London: Anthem Press

3. Sachs Jeffrey 2005 The End of Poverty: How We Can Make it Happen in our Life Time London: Penguin Books

Published on June 20, 2023 00:38

June 12, 2023

Unveiling the invisible hand of government in economic activity with the internet and education as examples

This post is actually the record of a private discussion that occurred between myself and an investment banker. He has agreed that the conversation be reproduced here verbatim.

The stimulus for the idea of a session on the role of government in society came from the zoom session where I presented my book. That session eventually devolved into a fierce debate about what are the proper limits of government’s role in society with you forcefully arguing that its role should not go beyond ensuring the peace and security of the state and though you didn’t say this, you would probably agree to the enforcement of contracts in addition to ensuring peace and security, with you specifically stating it had no place being an economic actor and even managing schools, citing our fintech sector and the internet in general, and education (I am guessing higher education) in America as examples of areas that thrive because of the lack of government involvement.

I personally feel your choices of internet fueled economic activity and higher education (in fact education in general but in terms of statistical data I shall only be concentrating on higher education) are somewhat misleading, and in the case of education, quite mistaken, but before I go into that I would like to make a general point. There is no country in the world today whose government has no role beyond providing security and the enforcement of contracts, in other words, a purely free-market system. The last time anybody probably had a free-market system was 1920s America. That is roughly a 100 years ago. That system ended with the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s. From that point on till present, governments around the world, including the US and UK, the world’s most market-friendly nations, have thought it necessary to actively intervene in the workings of the economy despite the free-market gospel they constantly preach. Businessmen world over may bicker about this but there is little to suggest that the world has any plans to return to a purely free-system similar to what obtained in the 1920s, though there has been significant amounts of privatization/deregulation/liberalization since the 1980s.

Having got that out of the way, I would like to highlight the decades of investment made by the US government in building the underlying internet architecture without which, there would be no fintech sector anywhere let alone Nigeria and also how mistaken your notion of US government’s non-involvement in higher education is. To buttress the fact about the US government’s critical role in pioneering major technologies, I point out how Apple, arguably the most prominent symbol of corporate innovation was dependent on the US government and university labs for many of the breakthrough technologies embedded in its iconic product, the IPhone (and IPod).

The internet was a project started in the 1960s by a U.S government agency known as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) (The same DARPA originated many of the technologies that found its way into the Personal Computer but that is another story). The impetus for the project was to build a communications network that could withstand a nuclear attack. To achieve that it was decided that the network should have a distributed design. By distributed, I mean that there is no main processing node on the network functioning as the brain that sends information to the computers (as opposed to being distributed, this kind of network is known as the client-server model). With it being distributed, even if a nuclear attack were to take out part of the network, the rest of the network could continue to function. Now I should point out that while many of the scientists who worked on the project wouldn’t necessarily agree that the goal was to build a network that could withstand a nuclear attack, the bigwigs who funded the project and continued to fund the project for 2 decades, did so with the explicit aim of obtaining a network that could withstand a nuclear attack.

While one small but highly innovative company called Bolt Beranek Newman (BBN) won a competitive tender to build a crucial piece of equipment, a tender that IBM declined to take part in because it thought it was impossible to build to the specifications asked for (AT&T, the telecom giant was even worse because it was positively hostile to a key concept needed to make the internet work at scale because it thought the concept threatened its business) the vast majority of the intellectual work in conceptualizing the internet, in designing the underlying architecture and actually building the protocols required to actually transport data around the internet was done by government and university scientists. This would be the pattern for over 2 decades, during which funding required for continuous development was provided by government sources. It was only from 1992-1995 that companies would begin to get involved en masse with the internet and this was mainly because of the development of the World Wide Web.

You should note that the internet and the web are not strictly the same thing, though the two terms are used interchangeably mainly because since the development of the web in 1991, the two have grown together. Strictly speaking the internet is a text-based network such that in order to navigate it, you will need to have a firm grasp of sophisticated UNIX commands (UNIX is a mostly text based operating system favoured by engineers and scientists over graphical operating systems like Windows). The web was built by Tim Berners Lee, an employee of the European intergovernmental experimental physics research lab known as CERN (So again, the foundational work in building the web, didn’t take place in a company). He designed the markup language for designing web pages, Hyper Text Markup Language (HTML), the protocol for locating web pages on the web, Hyper Text Transport Protocol (HTTP) and the world’s first browser. Now the browser built by Tim Berners Lee wasn’t particularly user-friendly. Lee had envisioned the web as an academic research tool so it didn’t support images and only read one line of text at a time. Quite a number of people/groups would try and improve on his browser. One of them was a computer science student doing research at a research center called the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (Yet another example of foundational work being done outside company walls). His name was Marc Andreesen. He and a fellow researcher would build a browser called Mosaic that did support images. He did this as a result of feedback he was getting by spending a lot of time in internet chatrooms so he was highly attuned to what users wanted. Andreesen had an entrepreneurial itch, so he would eventually join hands with legendary tech entrepreneur Jim Clark to build the world’s first massively adopted commercial browser called Netscape Navigator. It was from this point companies started piling onto the internet in droves and the internet started to resemble what we have today.

I had said earlier that I was going to discuss how the IPhone (and IPod) was crucially dependent on a number of technologies developed in government and university labs. What Apple mostly did was integrate these technologies into one slick package (an admirable feat in itself). Some of the technologies on which the IPhone is dependent, that were built in government or university labs include the internet just discussed, Global Positioning Systems (GPS), touch-screen displays, giant magnetoresistance (GMR. I don’t want to go into the details of this, it is needlessly technical. Just note it was crucial to enabling the IPod store so much digital content. This breakthrough was also important to other hard disk makers like IBM and Seagate), Liquid Crystal Displays (LCD), lithium-ion battery technology, SIRI the ‘virtual office assistant’, cellular communication technology etc. While the microchips that make the IPhone smart were built by private companies, most of them went from shaky start-ups to stable corporate giants by feasting on contracts from government agencies like the US Airforce and the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA). This was a form of government industrial policy to help build the semiconductor/microchip industry. Finally, even more government industrial policies have helped ensure companies like Apple have survived through good and bad times. Much of what I said in relation to the internet, the US has done or is doing in other industries like aerospace, clean energy, nanotechnology etc. You might argue that much of this does not apply to Nigeria since we don’t carry out such research intensive economic activities. Well, we should. That is where the wealth we are all clamoring for will come from and not doing so is what keeps us mired in poverty. Besides, such government activity will be required for the more mundane but no less important manufacturing sectors that need rejuvenation like textiles, paper production, leather products etc.

Now that we are done with the issue of the internet, let us face public schooling. Most nations understand how critical education is for effective citizenship, America is no different, in fact it has to be considered a leader in that regard, with much of the rest of the world emulating it, including ourselves.

America’s founding fathers, back in the 18th century, understood that preserving their fragile democracy would require an educated population that could understand political and social issues and would participate in civic life, vote wisely, protect their rights and freedoms, and resist tyrants and demagogues. To that end, they knew that instituting a formal system of public schooling was necessary and they went ahead to do just that. I will spare you the details of the evolution of their public school system but I will share with you some facts about American tertiary education (I am leaving out the lower levels. That would be too unwieldy) as it stands today.

America has at least 682 public universities affiliated with the various states. It also has about 1,462 community colleges (sometimes referred to as junior colleges, as they offer two year programs instead of four) of which 1,047 are public and 415 are private. It also has 29 public liberal arts colleges. Liberal arts colleges tend to be small and private (They also tend to focus on critical thinking and a general understanding of how the world works as opposed to achieving competency in a single discipline, which is the focus of a typical large research university). The private ones number more than 650. There are about 1,687 private, non-profit schools (The likes of Harvard, Stanford are included here). The private liberal arts colleges are also included in this number. There are about 685 for-profit universities. In all, the US has over 1,700 public institutions of higher learning.

One interesting but not very important fact, I share it just for enlightenment and amusement. In terms of reputation and prestige, the private, non-profit schools are generally the most prestigious. Like I said this is where you have Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Stanford, Cornell and others. Next in terms of prestige are the state public universities. Some of them are as well regarded as the likes of Harvard. Examples would be University of California at Berkeley and University of Michigan (Barack Obama’s younger daughter chose to attend University of Michigan unlike her elder sister who chose Harvard). The private, for profit universities are generally not esteemed. It is widely believed that anybody who chooses to attend these schools is academically deficient and does not have what it takes to survive at a private, non-profit school or at a public university (Most public universities are state universities. Very few public federal universities exist in the US). They are disparagingly referred to as “diploma mills”. George Weah attended one of these diploma mills before he became president (Disclaimer: I am a fan of George Weah. Just noting that he went to one of these schools). Not sure where the community colleges rank but definitely, they will be after the private non-profits and the public state universities.

The conversation will continue in my next post.

BEFORE YOU GO Please check out my book Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe

Bibliography

1. Hafner, Katie and Lyon, Martin 1996 Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet New York: Simon and Schuster

2. Mazzucato, Mariana 2013 The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs Private Sector MythsLondon: Anthem Press

3. Wikipedia article on Higher Education in the United States https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highe...

Published on June 12, 2023 00:08

June 2, 2023

A Secular Model of Marriage and a Data Driven Analysis of Polygamy

This is the continuation of my last post.

In the 18th century, a new, secular model of marriage began to evolve, which is known as the Enlightenment Contractual model. It is the dominant model of marriage in operation in the western world today. We would do well before delving into the model to understand what is meant by the Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment was an 18th century intellectual movement inspired by the stunning successes of the Scientific Revolution of the previous century, most notably the emergence of Newtonian Mechanics, named after Isaac Newton, whose essence is comprised of Newton’s laws of motion and his work on gravitation. The likes of Newton, Johannes Kepler, Galileo and others produced a scientific and rational basis for understanding the natural world and the universe at large. Influenced by this, some leading western thinkers of the 18th century were determined to find out if a scientific and rational basis could be found for understanding the underpinnings of society. That movement was known as the Enlightenment. You can learn more about it in my book, Why Africa is not rich like America and Europe. The Enlightenment was sweeping in its scope. It remade every facet of western society. Its values and ideals undergird everything from science, to the economy, to politics and representative democracy, to the notion of human, individual and natural rights and society. Basically, the Enlightenment’s values and ideals serve as the basis for western political, scientific, legal and social institutions. The very same institutions we in Africa have imported in the hope of emulating western material success.

Given how far-reaching the Enlightenment was, it would be surprising if it didn’t have some form of effect on marriage. Taking inspiration from the work done on social contract theory by thinkers like John Locke and Jean-Jacque Rousseau, the Enlightenment contractual model of marriage stressed the natural and legal rights of each member of the household as opposed as to the traditional biblical duties of each member of the household stressed by the Christian models [1]. It also placed a premium on the principle of equality of the marriage couple. It also made room for the dissolution of the marriage if the natural and legal rights of any member was violated. It no doubt plays a crucial part in the spike seen in the number of divorces globally in the last few decades. The enlightenment model stripped marriage of its sacramental, social, covenantal and commonwealth overtones and left only its contractual core, where the terms of the marriage were created and agreed upon by the couple [2].

I think it is worth pointing out that the enlightenment model of marriage didn’t only come about as a result of the Enlightenment reforming everything it touched. It partly came about as a specific response to the abuses that sometimes trailed the traditional Christian models in practice [3]. For instance, parents often abused the privilege of parental consent by coercing their children into marriages of their own choosing. Also, some members of the clergy used the doctrine of church consecration to probe deeply into the intimacies of the faithful, to extract huge sums of money for marital consecration and to play matchmaker against the wills of the marital parties or their parents [4]. The abuses suffered by women and children at the hands of the male head under the traditional regime is well known. Illegitimate children had it the worst as they were often aborted or smothered at birth. If they survived, they typically had severely truncated civil, political, and property rights [5]. It was these abuses the enlightenment model sought to correct.

I have taken the trouble to write this two-part essay on the European Marriage Pattern (EMP) and the five models of western marriage because given our embrace of market economies, the influence of Christianity, and our adoption of western social, legal and political institutions on the African continent, these models play a heavy role on our thinking about marriage even if we our unaware of their existence. Making the source of these models explicit will no doubt help improve our understanding of the institution of marriage.

I realize this account of the history of marriage is incomplete as I have neglected to discuss the influence of Islam and traditional African religion on marriage. Such an account will take more time and energy than I am willing to devote to the subject of marriage. My explicit aim was merely to write an account of the evolution of romantic marriage. By romantic marriage I mean marriage based on love, consent and freedom of choice as regards marriage partner. This form of marriage clearly had its origins in 13th century Europe and co-evolved with the emergence of the market economy, the Christian and enlightenment models of marriage. I will say this though in regards to Islamic and Traditional marriage; to the extent that muslims and traditional religion adherents take part in the market economy, it is reasonable that their marriage patterns would evolved in a similar direction as the EMP, that is you would expect Islamic and traditional marriages to be increasingly based on consent, love, and freedom of choice as regards marriage partner.

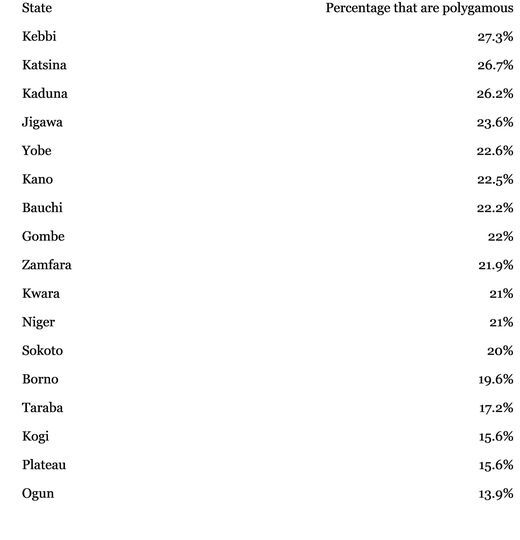

I will also say something about polygamy (specifically about polygyny where a man marries more than one wife). Polygamy was largely the norm everywhere until about the 6th century AD. Between the 6th and 9th century, things started to change in Europe as the Catholic church insisted that men could only take one wife and had a protracted battle with the European kings and nobility about this [6]. The church would eventually prevail and monogamy became the norm in the west. I think it is also worth pointing out that while polygamy permits marrying more than one wife, most men in places and times that permit polygamy, would of practical necessity have had at most, one wife. The laws of sexual inheritance from the field of Mendelian Genetics taught in about every secondary school biology textbook places significant limits on the number of men that can practice polygamy. As Mendelian Genetics ensures that in any suitably large population, roughly equal numbers of males and females would be produced, there simply wouldn’t be enough women to go around for the vast majority of men to have more than one wife. For the skeptics who need hard data, the following table is from the data service Statisense, which shows the top 17 states with the most polygamous men (ages 15-49) with at least 2 wives in Nigeria:

As you can see, no state has a percentage over 30. You will agree that less than 30 out of 100 does not constitute a majority. I would also add that it stands to reason that there are bound to be men who ordinarily under monogamy might have had one wife, who under polygamy wouldn’t have any at all because in the competition for women, some single men may find themselves losing to married men. As a result, there will be instances where children born to a 2nd or even 3rd wife, would under monogamy, still have been given birth to. The only difference is that they would have had a different father. All this leads me to suspect that the excess of population that polygamy might produce over monogamy isn’t all that much. A 2019 estimate of the population of Northern Nigeria vs Southern Nigeria put the figures at 128 million for the north and 92 million for the south [7]. The southern figure is about 71% of the northern figure. One would think with the way people talk about polygamy that the northern figure would be at least double. Furthermore, I do not think that polygamy is the biggest factor for the difference. I think the greater incidence of poverty in the north and the significantly less usage of contraceptives in the north bear a greater responsibility and the two are linked. The National Bureau of Statistics issued a press release in November 2022 stating that 65% of the multidimensionally poor are to be found in the north, with the incidence of multidimensional poverty ranging from 27% in Ondo to 91% in Sokoto [8]. I have explained in a previous post on the demographic transition how poverty in its own pernicious way, fuels population growth. In poor families that rely on a subsistence mode of existence, children provide a source of labor on the family farm and a form of insurance/pension for aged parents. Now when this is the case, you are not likely to want to use contraceptives even if provided free of charge. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), over 70% of Nigerians engage in the agriculture sector mainly at a subsistence level [9]. This is in stark contrast to the US, where 1.3% of the people are farmers and they produce enough to feed over 300 million people and export 20% of their produce. Clearly, those people are not practicing hoe and cutlass agriculture.

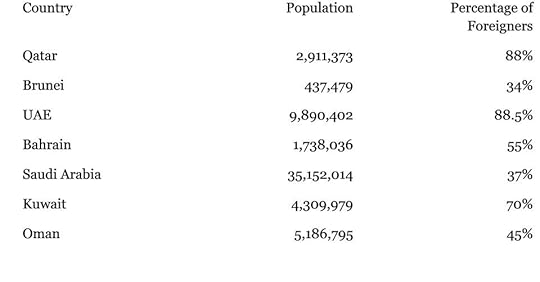

There is more proof for this point of view when you consider a number of Arab nations. Arabs are muslims and so are permitted to practice polygamy but have rather small (sometimes very small) populations. Here is a selection of them. The seven listed here are the wealthiest oil producers:

As you might have noticed, they all have significant foreign populations, sometimes majority foreign populations, so the actual number of Arabs is significantly smaller, sometimes much smaller. One would have thought that the combination of extreme oil wealth and embrace of polygamy would have led to a population explosion but it hasn’t. In fact, it is far from it. The reason for this is that Arab nations have generally reached at least stage 3 of the demographic transition, while most sub-Saharan African countries are at stage 2. I explained the demographic transition in a previous post. Finally, the political and demographic history of Lebanon might prove instructive. Lebanon, like Nigeria has significant christian and muslim populations. In the 1950s, the christians outnumbered the muslims by a ratio of 5 to 4 and this demographic reality was reflected in their parliament [10]. By the 1970s, the muslim population had outstripped the christian population as a result of the high birthrate among the Shi’ite muslims. The muslims asked that the sharing of seats in parliament reflect the new demographic reality and the christians refused [11]. This played a crucial role in the onset of the Lebanese civil war that spanned about 15 years from 1975 to 1990. In recent times as a result of more urbanization and modernization, the muslim birthrate has been increasingly converging on the christian birthrate.

I will end on this note. I had pointed out that our embrace of the market economy on the African continent had led to the EMP (that is marriage based on love, consent and free choice regarding marriage partner) to be increasingly, the dominant marriage pattern on the African continent (at least in urban areas). That, coupled with increasing urbanization, inevitably leads to a significant increase in the number of people who will remain unmarried despite seeking a life partner. While I commiserate with people, particularly females affected by this, you need to stop blaming the witches in your village for things they are probably innocent of. I won’t be surprised if young witches seeking a partner also blame other witches for their inability to find a life partner. I mean where does it all end?

References

1. Blake, Jenny H. Sep 1999. ‘The History and Evolution of Marriage (Review of From Sacrament to Contract by John Witte Jr.)’ BYU Law Review Volume 1999 | Issue 3 Article 5

2. Ibid

3. John Witte Jr. Oct 2002 ‘The Meanings of Marriage’ firstthings.com https://www.firstthings.com/article/2...

4. Ibid

5. Ibid

6. Ghose, Tia Jun 2013 ‘History of Marriage: 13 Surprising Facts’ livescience.com https://www.livescience.com/37777-his...

7. National Bureau of Statistics Demographic Bulletin 2020

8. National Bureau of Statistics Nov 2022 ’Nigeria launches its most extensive national measure of multidimensional poverty‘ nigerianstat.gov.ng https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/news/78

9. FAO team ‘Nigeria at a glance’ fao.org https://www.fao.org/nigeria/fao-in-ni...

10. Friedman, Thomas L. Aug 1990 From Beirut to Jerusalem New York: Anchor Books

11. Ibid

Published on June 02, 2023 00:35

May 23, 2023

Romantic Marriage: A Socioeconomic history