Stephen Birchard's Blog

October 21, 2024

Bees and Flowers: An Electric Attraction

It was a quiet afternoon in the colonial city. People were out and about in the streets, shopping and discussing the day's issues with friends. The sun was shining, but there was a hint of storminess in the western sky. Black clouds slowly took shape, casting shadows over the buildings and outdoor markets. Brisk winds began to blow, and a sprinkle of rain lightly danced on the cobblestones. Thunder rumbled in the distance, and a flash of light illuminated the ominous sky. To most of the city’s residents, it was a signal to find shelter, but to others, it was the perfect time to go outside.

He’d been waiting for weather like this; now was his chance. He grabbed his contraption made of cloth, hemp, string, and wire, and he and his son hurriedly found some open space, an empty lot suitable for the experiment. The storm was closer now, the thunder louder and lightning more frequent. He adjusted his homemade kite, then ran with it until it was airborne, letting string out a little at a time. He tied a metal key to the string where it would be close to his hand.

The storm was in full swing now, with thunder booming and frequent lightning illuminating the field. Rain soaked the kite and string. Then, something happened that he had predicted and hoped would come to fruition; the hemp’s tiny loose filaments seemed to get a mind of their own. They began to perk up like little hairs. The kite-flying scientist marveled at the sight of it. The hemp was affected by the storm’s electrical energy. When he slowly moved his hand closer to the key, an even more incredible thing happened: a spark traveled from the key to his knuckle. It was the most wonderful shock he had ever received.

With his clumsy apparatus, Benjamin Franklin, standing in a vacant lot in Philadelphia during a dangerous storm, confirmed that lightning was electric. The accounts of his experiment went viral.

We now know that electricity is present not just in lightening, but in nature as a whole. Electric eels, static electricity in our homes, and nerve conductions in our bodies are all based on electrical charges. Our hearts use indigenous pacemakers and an intricate electrical network to stimulate its muscle to pump blood, and similar elements create peristalsis which moves digested food down the gastrointestinal tract.

Recently, research has discovered another example of how organisms use negative and positive charges to their benefit. Bees and flowers have a wonderful symbiotic relationship, and in their quest for nectar bees are attracted to flowers, which results in pollination. The bees get food and in the process, the plant reproduces.

Bees are attracted to flowers by their brilliant color and aroma. But that’s not all. Experiments have shown that bees have a slight positive charge, and flowers a negative charge, leading to a beautiful example of how “opposites attract.” When a bee approaches a flower, this bipolarity causes tiny hairs on its head to vibrate, signaling to the bee that it should visit this source of nectar. As the bee gets closer, the electric charge is potent enough that the pollen literally jumps from the flower to the bee. Once the bee has taken the nectar and stored the pollen on its body, the flower’s negative charge dissipates and becomes more neutral. When other bees immediately approach this flower, they don’t sense the bipolarity and thus search out different flowers, making their quest more efficient.

Naturalist Sir David Attenborough demonstrates the process in this video:

https://www.tiktok.com/@uandyesterday/video/7324052002273529121

Earth’s magnetic fields, lightning, positive and negative charges in nature, currents running through our bodies . . . all forms of electricity that surrounds us, is inside of us, and binds us to nature. Bees and flowers serve as an example of electrical energy in the world around us.

"The day when we shall know exactly what electricity is will chronicle an event probably greater, more important than any other recorded in the history of the human race. The time will come when the comfort, the very existence, perhaps, of man will depend upon that wonderful agent." ~ Nikola Tesla

References

Shahmshad Ahmed Khan, Khalid Ali Khan, Stepan Kubik, Saboor Ahmad, Hamed A. Ghramh, Afzal Ahmad, Milan Skalicky, Zeenat Naveed, Sadia Malik, Ahlam Khalofah & Dalal M. Aljedani. Electric field detection as floral cue in hoverfly pollination. Scientific Reports (2021) 11:18781.

Dominic Clarke, Erica Morley, Daniel RobertThe bee, the flower, and the electric field: electric ecology and aerial electroreception. J Comp Physiol A (2017) 203:737–748

Zakon HH,www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.160...)

May 20, 2024

The Meadowlark "Springs" To Life

Dr. Ron Bright, author

“As February fades away, Spring is in the air and all thoughts turn to birding” (Clellie Lynch, the Berkshire Eagle, February 22, 2023). In the April, 2022 issue of Nature’s Almanac by Scott Severs, Ruth Carol Cushman, and Steve Jones, they described the meadowlark as a “Prairie Flutist and one of the best songsters of the world, labeling them the master singer of any worthy pasture, open-space parcel or grassland along the western slopes of Colorado.”

Here in the West, where my family lives, we are on a ranchette with prairie-like grass field topography surrounded by foothills and red rock formations. Woodland features are about ½ mile to the West of us. I mention this because of a long-running friendly bet my wife and I have had with friends who live 3 miles south of us within a hilly wooded area. The winner of our bet is the first to spot the Western Meadowlark each year, usually in February. After 2-3 years of winning the bet, we were asked to verify the migrating meadowlark’s arrival. So, I secured the evidence I needed the following year using my telephoto camera. But even that physical evidence was insufficient because we now have ‘wintering over’ meadowlarks, which would give us a “false positive” on identifying the returning population of migrating meadowlarks. So, we were challenged to move from visual to auditory verification. We collectively led ourselves to believe that the first day we hear songs in February are not the local wintering birds but the happy returning ones. This makes for a ‘sound’ rationale in our minds, and we are not inclined to allow ourselves to be corrected! For the first few years after that, I sent our friends a recording of the first day of our meadowlark spotting. Now, the auditory proof of the returning meadowlark is the gold standard!

Our betting friends and I shared a bird-watching trip to Panama ten years ago. This, coincidentally, happened to be in February, and when my friend screamed in delight that, alas, SHE was the first to spot the meadowlark that year (in Panama). I reminded her that Panama was east of the Mississippi. Our bet was still open because her identification was much more likely the Eastern Meadowlark and not the one native to our home habitat!

To say the welcome sound of the first meadowlark of the year is nothing short of thrilling would be an understatement. It provides a glimmer of hope that Spring will arrive soon! (Sorry Punxsutawney Phil). This blog will concentrate on the Western species, but most of my writing also applies to the Eastern version.

The meadowlark is not a handsome bird. They morphometrically are, as Sibley states, “a stocky and somewhat awkward-looking bird with a short tail, long bill, and legs.” The male’s outstanding physical features are the yellow chest and underside, with a plunging black “V” on their chest, contrasting beautifully with the bright yellow. They have a relatively slow flight speed and usually stay close to the ground. Their flight pattern is easily recognized due to their rapid, stiff wing movements, progressing to a glide.

The Western Meadowlark's range extends from northern Mexico to central and western North America. They prefer to build their nests on the ground covered with grass, which camouflages and protects them well. Foraging for food is typically on the ground and includes insects, berries, grain, and grass seeds. Where I live in Colorado, most Western Meadowlarks migrate to the southernmost part of their range (primarily Mexico). At the same time, some will remain here all winter, and more are doing that than ten years ago.

While the meadowlark may not be the most handsome of the aviary species, its songs are amongst the most beautiful, making one forget their outward physical appearance. “A Western Meadowlark’s joyous burble takes us to a sun-drenched prairie, with the wind whistling through the fence wire!” (Julie Zickefoose in Nov/Dec 2022 Birdwatcher’s Digest (BWD) page 63). The songs have contributed to making meadowlarks the state bird in 6 states. Besides their melodious multiple-note songs (a series of warbles and whistles with a soothing flute-like gurgle), they also have a single sharp note when other birds or humans intrude on their territory. They also have a series of calls they give while in flight. One of my favorite sounds is a double note, which is often heard when they are perched on a fence post. (see figure 1)

To see a video and hear their song, visit the All About Birds page on “WESTERN MEADOWLARKS” by Scott Severs.

Here is a photo (Fig. 2) of a meadowlark in full song mode belting out its flutelike sounds.

Building their nests is risky since they are on the ground and covered with grass woven over the eggs. The nesting area of a female is approximately 5-10 acres. The location of these nests makes them vulnerable to hikers, farmers and ranchers, and domestic and wild animals. It takes about two weeks for the eggs to incubate and another ten days for the young to leave the nest. The males do none of the incubation and brooding, and the females feed most of the hatchlings. A group of meadowlarks is known as a “pod.”

A sign of Spring, virtuoso singer, and striking appearance make the Western Meadowlark a remarkable bird. We are blessed that it shares with us our little piece of the world here in Colorado, and each year we eagerly anticipate its return from winter travels.

Please comment below if you have experiences or thoughts about this beautiful bird, the Western Meadowlark, or its cousin the Eastern Meadowlark.

February 28, 2023

Bald Eagles Are Nature's Rocky Balboa

As I drive across the bridge over the reservoir, I spot it circling high overhead. At first, I thought it was a turkey vulture. We have so many here; they frequently dot the sky, soaring and catching thermals to lift them to greater heights. But then, even so far away, I see a flash of white from the tail. I pull the car over and stop. I need a better look. Then another flash of white, this time from the head. Is it possible, right here, a mile from my house? It swoops by closer to me. No doubt about it; I’ve just been privileged to see our national symbol, and so close to home!

No words can adequately describe this bird. Majestic comes close, even regal, but some things defy characterization by language alone. You must see it and then take a moment to appreciate how it made you feel. Like other natural wonders, the Rocky Mountains, the redwood forest, Niagara Falls, or the Boundary Waters of Minnesota, it takes your breath away.

Knowing that a bald eagle shares this neighborhood with me is exhilarating. It also gives me hope. The eagle is an example of how we can undo the damage we’ve done to nature. When we decide it’s worth our time, money, and energy to heal the wounds, it can be successful. We are intimately connected to nature; when we repair the damage, we heal ourselves.

The bald eagle’s saga is a Rocky Balboa story. Both were underdogs in their fight for survival. Rocky's foe was Apollo Creed, the eagles' foe, us. In our zeal to control disease-carrying mosquitoes, we developed chemicals to kill them. The effort was effective, but collateral damage nearly wiped out our nation’s avian symbol. It was a punch in the face to the birds; the bald eagle species lay bloody and beaten on the boxing ring mat.

But like Rocky, the bald eagle was down but not out. DDT was killing the species by making their eggshells so soft they couldn’t produce chicks. Thanks to activists like Rachel Carson, awareness of the problem led to DDT being banned in the US in 1972. (see https://www.natureloversdigest.com/post/my-nomination-for-woman-of-the-century-biologist-rachel-carson-here-s-why) (Unfortunately, it is still used in some countries.) We also protected the birds from hunters and restored their habitat. We invested in the species, and it worked. Their numbers have grown; now, over 300,000 in the US. They even live in our neighborhoods.

It would be easy to pat ourselves on the back and point to the bald eagle as a success story in environmental conservation. It exemplifies how we can right a wrong in our quest to save nature and, as such, a cause for celebration. But questions remain.

When so many species are threatened with extinction, why did we save this one? Is it because the bald eagle, like the Liberty Bell and the Statue of Liberty, is a national symbol, a visual representation of our freedom? Is it because it is majestic, beautiful, and awe-inspiring? No one questions our commitment to saving these amazing birds of prey. But which other endangered species, both plant and animal, will we protect?

We saved the bald eagle; will we save the Florida grasshopper sparrow? We’re trying to save monarch butterflies; will we protect the rusty patched bumblebee? We’re trying to save Alaskan salmon; will we save the Beluga sturgeon? We’re trying to save the redwood forests of California; will we protect the pitch pine forests of the New Jersey Pine Barrens?

Human beings are self-centered. We rescue species that benefit us in some symbolic, scenic, or commercial way. But will we also invest in others whose value is simply that they share the planet with us? Being connected to nature means being connected not only to the bald eagle but to all of it; tiny birds, weirdly shaped fish, insects that can sting us, and short scrubby pine trees that grow in the forests of New Jersey. The bald eagle taught us what's possible. Have we learned from that lesson? Time will tell.

“Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.”Albert Einstein

References

Megan Evansen. Saving the Bald Eagle, a Conservation Success Story. https://defenders.org/blog/2023/01/saving-bald-eagle-conservation-success-story

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Final Report: Bald Eagle Population Size: 2020 Update. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2020-bald-eagle-population-size-report.pdf

August 31, 2022

Rethinking the Suburban Lawn

Saturday morning; time to do one of my weekly chores before the summer sun makes the work unbearable. I open the garage door and pull the lawnmower out. It is a manual mower, a simple machine of horizontal blades connected by an axle to the wheels. The mower’s source of power is the human operating it. Gasoline-powered lawn mowers were not standard in those days. When it is pushed, the blades rotate and cut the grass. Considerable effort is required to go through thick turf, but that wasn’t a problem with our tiny lawn, which was a collection of grass, dandelions, clover, and other assorted weeds. My father used to say, “If it’s green, let it grow.”

Back then, lawn maintenance was simple; you mowed the grass every couple of weeks. The lawn’s primary function was to cover the ground so we could play on it. We lived on a small lot in a blue-collar neighborhood. The residents of our street kept their properties tidy but had minimal concern for the front yard's appearance other than grass mowing and 1 or 2 pots of flowers by the front door. Very different from the elaborate suburban lawns of today.

Modern-day lawns are immaculate, manicured, weedless, bug-free carpets of green.

They look like miniature golf courses. They are maintained with power mowers, edgers, and leaf blowers. Artificial chemicals fertilize, kill weeds, and prevent insect infestation. Lawn maintenance companies come to the house five or more times per season to apply these chemicals, riding gasoline-powered tractors to disseminate the liquid and granular treatments. Irrigation systems are used to water the lawns regularly to keep the grass green and growing.

But this obsession with the perfect lawn comes at a cost. The average lawn receives ten times the fertilizer application farmers use on their fields, and much of this inorganic fertilizer drains into the groundwater. This pollutes lakes and streams and causes the growth of toxic algae, which harm fish and contaminate drinking water. Chronic exposure to herbicides and insecticides on lawns causes cancer in animals and kills beneficial insects like pollinators, including the endangered Monarch butterfly. Studies have shown that these chemicals are present in the circulating blood of our pets and even us.

The gas-guzzling machines we use to mow, trim, and blow away grass and leaves are inefficient, using an estimated 800 million gallons of gas per season in the US.

They are not subject to the same pollution controls as cars and trucks. Five percent of the total US air pollution comes from these machines. A gasoline leaf blower releases more carbon into the atmosphere than a pickup truck, and they contribute to noise pollution in our quiet neighborhoods.

But what are the alternatives? Lawns have some redeeming environmental value, such as keeping the underlying soil cool and not reflecting the heat from the sun. They provide areas for children and dogs to play and adults to engage in sports and have picnics. Complete eradication of grass is not the objective, but organic methods to maintain the lawn and conversion of at least some of it to more environmentally friendly gardens should be considered.

Five ways to a “greener” property with lawn alternatives :

1. Plant trees. They add interest to your property, reduce heat and attract birds and beneficial insects. Studies have shown that people that live in neighborhoods with trees are healthier physically and mentally.

Adding trees to your yard is good for you and the earth! The arbor day foundation has a very helpful “Tree Wizard” to help choose suitable tree species for your needs.

2. Convert areas to perennial gardens. Select native, low-maintenance plants that add beauty to your yard and provide habitat and food for pollinators and birds. Here in the Midwest, some good options for perennials are hostas, coneflowers, black-eyed Susans, and daylilies, to name a few.

3. Plant ornamental grasses. They are easy to grow and add interest to the property even in winter when they turn light brown and develop seed heads. They are great hiding places for suburban wildlife like rabbits, squirrels, chipmunks, and toads. Feather reed grass is prevalent on our property in Indiana; it is not a native plant but is non-invasive and low maintenance.

4. Start an organic vegetable garden. It doesn’t have to be a demanding, labor-intensive activity. A single raised bed using a frame of cedar wood planks filled with topsoil and compost provides an excellent way to start growing nutritious food. Tomatoes, green beans, peppers, and herbs like sage, basil, and oregano are easy to grow from seed or transplants. I use the “square foot” gardening method described by Mel Bartholomew; click this link to learn more about the technique described in his books.

5. Make your remaining lawn chemical-free. Let white and red clover grow naturally, and watch the bees and butterflies enjoy the food source. Clover is a legume that “fixes” nitrogen in the soil, adding a natural fertilizer for the grass. Mulch grass and leaves in the yard with the mower rather than bagging and discarding them. This increases organic material in the soil and adds nutrients.

Lastly, and maybe the most challenging change to consider is this: stop the war on weeds. They are not the enemy; they can help the environment by attracting pollinators and covering the bare ground. If there are certain ones that you can’t tolerate, put on your garden gloves, grab a trowel, and dig them up. It's good exercise and so much better than applying toxic chemicals.

Global warming, pollution of the environment, and declining bees, butterflies, birds, and other species are all issues that deserve our concern. What better place to act than our properties, the little piece of earth on which we live? For more information on making our yards better for the planet, see this excellent article from Princeton University’s Student Climate Initiative: https://psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/5/11/law-maintenance-and-climate-change.

References

http://drstephenbirchard.blogspot.com/2018/05/do-lawn-treatment-chemicals-cause.html

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-fertilizers-harm-earth/

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/brainwaves/outgrowing-the-traditional-grass-lawn/

https://www.arborday.org/shopping/trees/treewizard/Intro.cfm

https://www.natureloversdigest.com/post/monarch-butterflies-are-in-trouble-how-can-we-help

May 13, 2022

A Large Flower, A Small Restaurant, and a Country at War: What Do They Have in Common?

It was my first time inside the unpretentious little diner. We walked past the outdoor shelves of candy and newspapers stacked on old wooden boxes, then went through the front entrance. The dining area was small, like most eating venues in this city. There were a few tables, but most people were sitting at the counter on metal stools. They appeared to be eating a type of dumplings with sautéed onions and sour cream. Older men were reading newspapers with headlines I couldn’t understand. They sipped purple soup and ate thick slices of white bread. The patrons were speaking a foreign language. I had no idea what it was; they could’ve been speaking in tongues for all I knew. It was a noisy, crowded, bustling place. I felt like a stranger in a strange world.

But the waiters and waitresses seemed to recognize my parents and me. They smiled and greeted us in broken English. We were ushered into the “back room”, where only a select few important people were allowed. This room was quiet but dark and dingy. Paneled walls surrounded old wooden tables and chairs. Above us on one side was a loft that appeared to be an office of sorts. Those perched in the loft could see out and monitor the activities in the room. I imagined that only people of the uppermost rank were permitted in that high place.

My brother Tom and an elderly gentleman descended from the elevated headquarters and came to our table. The gentleman’s name was Wlodymyr Darmochwal, a stately man wearing a suit that was faded and worn. He owned the establishment. Tom introduced us to him and did all the talking since Wlodymyr, his father-in-law, only spoke Ukrainian. To my surprise, Tom was able to serve as interpreter. I guess being fluent in Ukrainian was necessary to work in this place. I soon learned that wasn’t all he was fluent in.

We ordered lunch and asked for the house specialties, those dumplings, and that purple soup. Our waitress also didn’t speak English, only Polish. No problem. Tom was fluent in that as well. When did my brother become so multi-lingual? Our orders arrived. The dumplings (pierogis) and the soup (borscht) were delicious.

This was our inaugural visit to Veselka, which means rainbow in Ukrainian. It has been my family’s connection to the Ukrainian community for the past 55 years. Tom started as manager, then part-owner, then sole owner. Over the years, he has transformed Veselka from a candy shop to today’s full-service restaurant. His son Jason, who is half Ukrainian, now runs the business. My son Justin was recently added as his sidekick. For years Veselka has been an icon of the East Village—now, it’s more than a restaurant; it’s New York City’s center for supporters of the Ukrainian war effort.

One of Ukraine’s symbols, and the unofficial national flower, is the sunflower.

I’ve always loved sunflowers; they are easy to grow, stately, and beautiful. There is nothing subtle about them. They boldly declare happiness, exuberance, and, well, sunshine. Today, along with the similarly colorful Ukrainian flag, they are symbols of the courage and determination of Ukraine’s defenders against Russian aggression.

The sunflower’s importance in Ukraine dates to the 18th century, when the seeds were considered their favorite snack, and the export of sunflower oil became an essential part of the country’s economy. Since the Russian invasion last February, sunflowers have become a worldwide symbol of support for the courageous Ukrainians who are valiantly defending their beleaguered country against a powerful foe. Even Jill Biden, USA’s first lady, recently sported a dress with a sunflower on the right sleeve.

I grew sunflowers long before I knew about their association with Ukraine.

I like how they look and love how they attract pollinators and birds to their flowers and seeds. I will expand my plantings this year, with one pot strategically located next to the Ukrainian flag hanging from my house. I want no doubt about which side of the war this household supports. My Indianapolis neighbors have asked: Are you Ukrainian? No, but Ukrainian blood runs through members of my family, and the Ukrainian spirit flows freely through the combined souls of the Birchard tribe.

If you visit New York City, head downtown to the East Village and drop into Veselka on 2nd avenue and 9thstreet. Order some of that purple soup since all proceeds from the sale of borscht go to supporting Ukraine in her struggle against an evil regime.

#veselka, #standwithukraine

May 4, 2022

The Deadly Shrike Strikes!

Many birds have behavioral characteristics that make them unique. One such bird is the shrike. Here is a smallish bird compared to the usual raptor, yet one that displays raptor-like qualities in predation. These little rascals could be considered brutal when securing their prey for dinner.

While there are over 30+ species of shrikes, we refer primarily to the Loggerhead and Northern shrike in North America because their breeding is limited to this area. The family’s largest genus is Lanius which is derived from the Latin word which means “butcher”! The Loggerhead, in particular, is known as the “butcherbird,” but both the Northern and Loggerhead are ruthless hunters. The English word assigned to this bird is from Old English “scric,” reflecting the shrike’s shriek-like sound.

Shrikes are innocent-looking, medium-sized birds with multiple plumage colors, but primarily black and white. They are often confused with the Northern mockingbird when flying because of their similar size and a prominent white wing patch. Their flight pattern consists of swift undulating wing movements with shallow rapid wing beats. They are roughly 8-10 inches long (Northern being slightly larger), and their beaks have a “hook” (more prominent in the Northern) which serves them well as they need this accessory to aid in their “kill” of prey. (Fig. 1) Besides the size differences between the Northern and Loggerhead, which is sometimes hard to differentiate when they are not seen together, the most helpful feature for identification is the black mask on their head that begins behind their eyes, courses across their eyes, and contacts the base of their beak. The mask is much broader in the Loggerhead, and its beak is stubbier and usually, but not always, lacks a prominent hook at the tip. In contrast, the Northern has a noticeable white eye “brow,” Its mask is thin and dark. The Northern also has a more hooked beak. The shrikes’ calls are strident and ‘shriek’-like.

Shrikes prefer open habitats. I see them on our property which is primarily pasture and prairie land with a few adjacent trees where they often perch looking for prey. They usually migrate to warmer climates during the winter, but recently (January 2022), I observed a male Loggerhead hanging around our feeder and surrounding grassy area. Typically, however, I encounter them in mid -April in our fields and on our barbed wire fences. The bird population at the bird feeder at this time consists primarily of house finches and juncos with an occasional American goldfinch. The presence of a shrike often results in the area around the feeder and the nearby trees becoming completely void of our usual bird activity. Smaller birds recognize the shrikes’ predatory tendencies and move quickly out of the shrikes’ territory.

Shrikes often perch on exposed fence posts (see figure 2, T-post perch), trees, and other elevated structures scouting for their next meal. They hunt insects, rodents, and small birds, and, after grasping their prey by the neck and killing them, they proceed to impale the bodies on thorns or man-made objects such as spikes on barbed-wire fences (figure 3- note its barbed mealtime accessory close by).

This impaling helps the shrike rip the bodies of their prey into smaller edible-sized fragments, but sometimes the meal is delayed, and the birds simply ‘cache’ their prey to consume later. Lubber grasshoppers, part of the shrikes’ diet, are toxic if eaten immediately after the kill. Impaling the lifeless grasshoppers and “storing them on a made-made object or thorn of a tree) allows the shrike to wait 2-3 days until the grasshopper ‘detoxifies’ and becomes harmless when ingested.

Loggerhead shrikes frequent our back pastures where there are Russian Hawthorn trees and an abundance of barbed wire fences creating a perfect hunting ground with all the amenities necessary to be a “butcherbird”!

March 5, 2022

Amaryllis: A Harbinger of Spring

“It was one of those March days when the sun shines hot, and the wind blows cold: when it is summer in the light, and winter in the shade."

- Charles Dickens

The days are getting longer. The sunlight invites itself in at a steeper angle, and the beams are warmer. Dogs seek comfort in them. The last piles of snow are helpless—being slowly absorbed back into the earth’s substrate.

Cardinals are the first to know. Their song becomes distinct, repetitive, and clear. It penetrates the cold stillness of early morning. Although their message is pragmatic, it is the song of Spring.

But it is early in the transformation. Wildflowers have not yet appeared, trees have no buds, and the grass is still brown. Even the ephemerals have not emerged from the cold forest floor. Early Spring is a season all its own. Nature is awakening from its hibernation but is still groggy.

Inpatient with nature’s methodical cycle, I yearn for a symbol of its resurrection. There are dormant amaryllis bulbs in the dank, dark corners of the basement. I bring them upstairs and implore them: “Wake up, unconscious bulbs. I offer clean water, sunlight, and warmth. Show me that first new leaf, tenuously peeking out from the atrophied remnants of last year’s foliage.”

Days go by. The exposed portion of the bulb doesn’t change. I look at it often, as if my gaze will spark the germination. But I know the schedule is not mine to dictate. Patience is an elusive virtue. Some call this process “forcing the bulb”; I see it more as “inviting the bulb.” By giving it light, moisture, and warmth, I am opening the door for it to declare its magnificence.

Finally, a leaf appears, then another.

A flower bud slowly breaches the confines of the bulb.

Then, almost before one’s eyes, a flower stalk reaches upward. It is robust, thick, and vertical—a botanical obelisk. How did all that green matter fit inside this Pandora's box of horticultural mystery?

Finally, it reaches its pinnacle, and the flower gently opens. It is revealed in all its glory. The petals are enormous.

Mythology holds that the amaryllis represents pride, strength, and determination. It’s easy to see why. Everything about it is grandiose. Mine are red, just one of the many available colors, including white, pink, salmon, apricot, and burgundy. Choose one that beckons to you.

Spend time drinking in their beauty, for their time is fleeting. The blooms will fade, but the leaves will remain and be nurtured through Spring, Summer, and Autumn. They need that time to prepare for next year’s brief but spectacular display. Three seasons of tender loving care for a few weeks of blooms, but it's worth it.

December 27, 2021

One of Nature's Annual Displays: Sandhill Cranes Visit Indiana

When we first arrived, there were no cars in the parking lot. More concerning was that there were no birds in the sky and no rattling bugle call from their throats. This was disappointing since I had spent the entire 2-hour car trip trying to convince my family that they were about to witness one of nature’s beautiful displays. Where were the birds? Had they all decided it was finally time to head to Florida for the winter?

Maybe we got to the wildlife refuge too soon. The sun had not set, it was about 4 pm. The birds usually return here at dusk after feeding all day in adjacent fields and marshes. Maybe they found a perfect field to have dinner and were reluctant to head back to their roosting area. Whatever the reason I yearned for a sighting of them to maintain some semblance of respect from my family who were becoming skeptical of the whole affair.

We decided to take a quick trip into town for something to eat, then return and hopefully see some birds. (Please let us see some birds!)

On the way back to the refuge we spotted a small group of them in the sky. Thank goodness at least some are still here! A handful of cars were now in the lot and a few dedicated bird watchers, dressed in abundant layers of winter clothing, were walking the trail to the observation platform. It was very cold; not perfect bird watching weather. But then we were in northern Indiana in December just a few days before Christmas.

A few more small groups of birds came in from our left, flying low. They were joining their friends in the roosting areas. I focused my binoculars and easily found them flying just above the horizon. Behind them were a few more groups, each one containing more birds. They were silhouetted by the setting sun and yellow-orange sky. Majestic in flight, their long necks were stretched out and 7-foot wingspan propelling them to their destination.

Gradually there were more, many more. They came in waves, groups of up to a hundred or more, one after the other. All flying from left to right in front of us, and all beautifully illuminated by the evening sky which was becoming more colorful as the sun dipped below the horizon. A few of them were making the trumpet call, announcing their arrival to all who will listen.

These are the Sandhill Cranes. Named after the sandhills of Nebraska, they are large, impressive birds. They are fun to watch as individuals, even more spectacular when they congregate in masses of 20 to 30 thousand which they do every fall. They stop at Jasper Pulaski Fish and Wildlife Area on their migration south to Florida for the winter. In the Spring they will head back to their summer grounds in the northern US, Canada, and Alaska. (see map below)

The cranes are large birds standing 3 to 3.5 feet tall. They have long necks, and an elongated beak that comes to a sharp point. A bright red crown sits above a white face, and bluish-gray and light brown feathers on the body. The tips of the wing feathers are splashed with black.

They are quite the talkers; the rattling trumpet call can be heard from birds on the ground and in flight. It is a unique sound that makes them easy to distinguish from other birds. I sometimes hear them flying overhead our home in Indianapolis, but their elevation makes them hard to find. Imagine how it sounds when they congregate on the ground in the thousands.

The cranes mate for life, and their monogamous relationship can last for up to 20 years or more. Divorce is uncommon. The females lay only 1-3 eggs per breeding season, and the immature offspring stay under their parent’s supervision for 9-10 months before striking out on their own.

The Sandhill Cranes are an exception to the plight of so many endangered species. Their numbers are stable. But their critical feeding, breeding, and roosting habitats must be preserved to keep them thriving, especially since they lay very few eggs each breeding season. Although the Jasper Pulaski area is preserved and safe, surrounding fields and marshes are privately owned and thus not protected. The birds need these areas; maintaining them in their natural state is critical.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said: “Adopt the pace of nature. Her secret is patience.” Nature’s pace invokes serenity, a sense of calm, even meditation. Today the Sandhill Cranes arrived on their schedule, not mine. The wait only made the sight of them more captivating. I am grateful for the image of their majestic wings silhouetted by the fiery colors of sunset. A Christmas gift like no other.

References

1. Jasper-Pulaski Fish and Wildlife Area. https://www.in.gov/dnr/fish-and-wildl...

2. The Cornell Lab. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Sandhill_Crane/overview

November 12, 2021

“We are Stardust”: How the iron in our blood came from the fiery furnaces of the cosmos.

“We are stardust, we are golden,And we've got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

Woodstock, Joni Mitchell

According to astrophysicists, the elements that make up our bodies, such as the calcium in our bones and the iron in our blood, were formed billions of years ago in distant stars in the universe. It is the same iron that was generated inside stars from the time of the Big Bang, that cataclysmic event that gave birth to all the suns, planets, and moons. As astronomer Carl Sagan said: “We are made of starstuff. The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars.”

In my mind this is the ultimate reality of how we are connected to nature. The building blocks of our bodies originated somewhere in the heavens, and we share this cosmic history with everything on earth: animals, plants, rocks, and soil. The chemical elements from the universe make up the molecules that comprise everything.

“The Star in You”, an article from the PBS series “Nova” written by Peter Tyson, describes how it all happened. The chemical elements in the periodic table, those substances that cannot be broken down any further through chemical means, were formed via thermonuclear reactions in stars that were contracting due to gravity at the end of their lifespan.

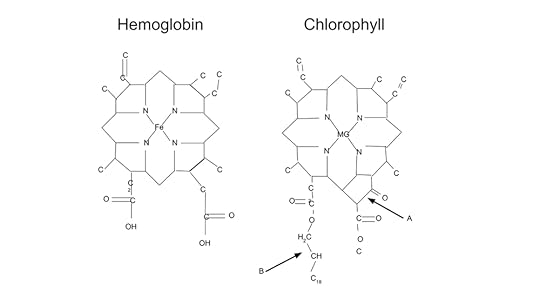

One of those elements is iron, chemical symbol "Fe". Iron is at the center of each molecule of hemoglobin in our blood. Hemoglobin is the essential part of blood that carries oxygen from the lungs to the body's tissues. Chlorophyll, a molecule practically identical to hemoglobin, allows conversion of sunlight to energy in plants. At the center of each molecule of chlorophyl is Magnesium, chemical symbol "Mg". Two metals, iron and magnesium, are essential for life on our planet and were produced in the universe billions of years ago.

When stars burn out and lose their mass, they release into space the elements that have formed inside them. New stars form and go through the same process, called galactic chemical evolution. Our own sun is going through this process right now. It is currently only hot enough to convert hydrogen into helium, a mere 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit. But when it evolves into a red giant on its way to burning out, it will become even hotter; hot enough to generate more chemical elements. But don’t hold your breath; that will not happen for another 5 billion years.

We marvel at the stars in the night sky, but their distance from us makes it hard to imagine we have any physical connection to them. Scientists have now traced the very basic elements in our bodies to those celestial bodies that sparkle above us. Without them and their galactic chemical evolution nothing here on earth, including us, would exist. We are inextricably linked to everything, including celestial bodies that are light years away.

From Carl Sagan’s book Cosmos*: “We have begun to contemplate our origins: starstuff pondering the stars; organized assemblages of ten billion billion billion atoms considering the evolution of atoms; tracing the long journey by which, here at least, consciousness arose.”

* I highly recommend Dr. Sagan’s book. I am re-reading it now for the third time. Although published in the 1980’s, it is as relevant today as it was then. He has a unique gift for describing the universe in an eloquent and captivating manner; combining science, philosophy, and poetry to show us why we should be awestruck whenever we look to the night sky.

References

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article...

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/are-we-really-made-of-stardust.html

Figure Credits

Figure 1: Pablo Carlos Budassi, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2: 2012rc, CC BY 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: Jcauctkting, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

August 24, 2021

Fly Fishing for Bass on Koteewi Lake

It’s a new lake, 14 years in the making. It wasn’t supposed to take that long; an economic recession then a pandemic slowed things down. It is part of a larger park in Central Indiana that includes prairies with abundant wildflowers, hiking trails, and activities like archery and zip lining. But the 20-acre lake is what I was focused on; and I couldn’t wait to launch my kayak on its smooth waters.

Before fishing an unfamiliar body of water its best to know the boating restrictions. In my little unpretentious kayak I'd rather not be surrounded by bass boats with powerful outboard motors capable of obtaining great speed while generating large wakes. Fortunately, Koteewi Lake is limited to canoes, kayaks, and other boats with trolling motors (capable of only 15 mph). The objective here is not speed and noise but rather a slow, quiet approach to explore the waters and find fish.

Koteewii Lake has other attributes. Its banks are rich with vegetation: small trees, bushes, and wildflowers. The fauna is pleasing to the eye and perfect habitat for bugs, amphibians, and birds. Some small areas have been cleared for fishing from the bank but most of the lake perimeter remains in its natural state. Whoever designed this little aquatic oasis understood nature, and fishing.

It was a gorgeous morning, and I had the lake all to myself. Only a slight breeze, water like glass, and a beautiful sunrise. The crystal-clear water was perfect for my preferred method of fishing, using a fly rod to cast dry flies toward the bank and retrieve them back to the boat. The fly imitates a frog, minnow, or large bug bouncing along the surface. Bass are not picky eaters; if it looks like a tasty morsel they will take it.

Before launching the boat, I like to pause for a few minutes to observe the water and surrounding area. Is there any wind, the water smooth and clear, any geese or ducks on the lake, and are fish visible near the bank or rising to eat surface insects? I also take this time to adjust my consciousness. I try to calm down, breathe slowly, be aware of my surroundings. Listen to the birds and the breeze rustling through the trees. I am visiting one of nature’s sanctuaries; I want to be respectful, to blend in and not be disruptive.

I quietly put my kayak in the water using the convenient canoe/kayak launch that is provided. I slowly paddle to the opposite bank to begin the search for fish. Thirty to 40 feet off the bank is a good position for the boat. I cast the fly to land close to the bank, then intermittently tug on the fly line to twitch the fly on the water. This is called “animating the fly”, or making it look alive. Although the conditions couldn’t be better for fly fishing, the first several casts yield no interest. Maybe the fish are not active, not feeding in this spot, or my clumsy casting is scaring them away.

When several casts over one area are unfruitful, I slowly paddle along the bank to a new spot. One of the first things to learn about fishing is that we don’t dictate the terms of the experience. They will bite when they want to. Patience is the order of the day.

After nothing more than a few feeble strikes on my fly from small bluegill, I paddle around a corner of the bank into a new area. Now some fish are striking the fly with more vigor, and one latches on. I tighten the line to set the hook, strip it to pull him in, and land the little bass to the boat. I quickly take a picture of the small but healthy fish, remove the hook, and slide him back into the water where he scurries away.

I then paused to take a deep breath. I think to myself the old fishing cliché: “The skunk has left the boat”. The fisherman’s lament is to get “skunked” which is to go all day without catching a fish.

I find that after catching the first fish I become a different angler. With the fear of getting skunked behind me, I’m more relaxed, patient, and deliberate. As a result, my fishing technique improves, which can lead to catching more fish.

I slowly paddle along the bank a little further. The sun is now higher in the sky and the air warmer. I look for some shaded areas of the lake where the fish may feel more comfortable rising to the surface. Water directly under overhanding tree branches sometimes holds fish; they are looking for bugs dropping out of the trees or even the occasional small rodent or bird falling into the water.

With a cast that puts the popper very near the bank a fish eagerly takes the fly before it even moves. It appears to be a small fish but is fighting hard and feels bigger than he looks, a tell-tale sign of a bluegill. I pull him into the boat and submit him to the usual inspection and photography process. He is very pretty, glistening stripes and the characteristic spot on the gill behind his eye. Back in the water he goes.

I paddle on, still holding the same distance from the bank and seeking suitable areas where more hungry fish may live. Bass love to hide in cover such as a downed tree under water, aquatic plants, or large rocks. Here they can ambush unsuspecting fish or other creatures for an easy meal. I see a large tree trunk under the water and begin casting over it. Initially there was no action, and I was about to give up and move on. I managed one more cast with the fly landing too close to the boat. Since poor casts usually do not result in any success, I hurriedly started to retrieve the fly line so I could resume my paddling.

Unexpectantly, just before pulling the fly back into the boat . . . the water exploded! With a big splash something hammered the fly and pulled it down into the darkness of the deep water. I pull the rod up to set the hook but the fish, in his maniacal desire to consume the fly, had already hooked himself. The rod bent severely; this fish was large, and strong.

Landing large fish is a skill all its own. Patience is the key; one must let the big ones do their dance until they’re ready to give up. Your tugging may get them close to the surface, only to have them dive down again and continue the fight. After playing this bass for several minutes, he finally tired and let me pull him into the boat.

He was a beautiful large-mouth bass; shiny, plump, and healthy. His image barely fit in the iphone camera. In my excitement to catch such a handsome specimen, I yelled “I love you!” before releasing him back to the cool waters. I took a deep breath. My day on Koteewi Lake was now complete.

For days after a fishing trip, I relive the experience. I think about the water, the weather, which fly I used on which rod, and what fish I caught. I ask myself what I learned and what I will do differently next time. Most importantly I wonder when I will come back, because for me fly fishing is a spiritual experience, and I count the days until I can do it again.