Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 68

April 10, 2013

Writing Wednesday 28: What You See

This week’s video is actually a topic I’ve blogged about before, some years ago, but I can only say the situation hasn’t gotten any better. I thought it would make a good vlog topic since I had those two recent experiences that so clearly demonstrated how poor my visual memory is, and that got me to thinking about how few visual descriptions (as usual) are included in this draft of my novel. By the time you read the novel I may have some idea what things and people look like, but those descriptions will have been added afterwards by conscious effort.

I’m terrible at seeing things, but I’m really good at hearing things. But that’ll be the topic for another vlog in the future!

April 6, 2013

Searching Sabbath 11: The Church

This was supposed to be posted last week but I was having problems with YouTube (which are still ongoing). It was meant to be a companion piece to my blog from last Friday about the dismissal of Pastor Ryan Bell from Hollywood Adventist Church. Events such as this really colour my view of what it means to be in “a church,” because while I think Christian community is absolutely essential — I don’t believe in individualistic religion — the hard fact is that it’s nearly impossible to form a community without drawing boundary lines. Who’s in; who’s out. Who can lead; who has to follow. And how do we deal with those who disagree with some of our core beliefs yet still want to be included in our community? How, in fact, do we even define our core beliefs?

These are the questions that drive me, not just in today’s video but, in a way, throughout this whole video series. I want to examine my church’s core beliefs and where I stand in relation to them but at the same time I feel the need to question this whole concept of having “fundamental beliefs” and how that relates to the lines we draw, and how we treat people who stand on the opposite side of these lines. And, as always, I look forward to discussion.

Note: I added this after I posted … if you watch this video in the context of last Friday’s post, you might also want to watch this farewell sermon from Ryan Bell … I’ve linked to it starting at the point where he talks about the Adventist church. Everything he says here is everything I believe about the church, what it is and what it ought to be. It’s just sad that that commentary is coming from someone who’s been told he’s no longer welcome as an Adventist pastor.

April 4, 2013

The Day Has Come!

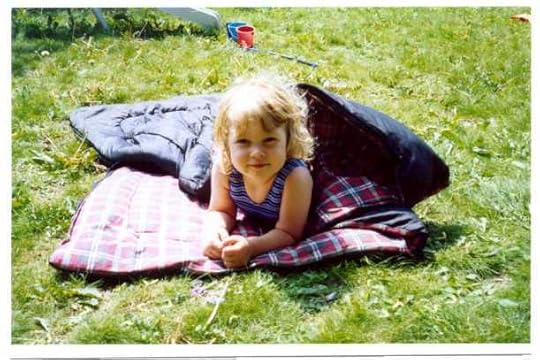

It was bound to happen … as soon as you have two babies, two toddlers, two preschoolers, the inevitable outcome is that someday you’ll have two teenagers. Today is that day. Emma turns 13 and I officially have two teens in the house.

I had the cutest picture I wanted to show you … from when the kids were about 5 and 7, and one day they dressed up with hats and both got into these sort of “rapper” poses, and said, “Look Mom! This is what we’ll look like when we’re teenagers!!”

It would have been the perfect picture to post today but what they don’t tell you is that when they’re teenagers, one of them will REFUSE TO LET YOU POST THE CUTE PICTURE. And you have to respect their wishes, because they’re practically adults and all. In some ways.

So I’ll just post my favourite picture of three-year-old Emma and tell you that she is even more beautiful now.

And even though they come with opinions of their own and rights to be respected, and I like to moan and groan as much as the next parent about the dread and fear of having two teenagers, I actually am sort of looking forward to it. I’ve always been more comfortable around teenagers than around little kids, and although there is all the difference in the world between relating to kids as a teacher or youth leader, and as a parent, I hope some of my relating-to-teenagers skills will continue to help not just with relating to my own kids but also to their friends.

So far I have to say that Chris has been an excellent teenager and Emma has been a great pre-teen so I’m expecting lots of fun and plenty of interesting conversations in the years ahead. The development of logical thought, independent opinions, and of course the judicious use of sarcasm, are real joys to me as my kids get older. That’s not to say there are no challenges in the teen years — they certainly do have their unique problems, just as every age does. But they have their pleasures as well and I plan to enjoy those to the fullest.

Clearly, I’ve got a great attitude today. Check back with me in a year or two. Maybe by then I’ll be allowed to post cute pictures again.

Happy birthday Emma!!

April 3, 2013

Writing Wednesday: Real People

Today’s vlog was definitely one of the most fun to make, as it had me dressing up (a little bit) as two different characters in order to talk about how I incorporate real-life characters into historical fiction.

A question for readers who love historical fiction: do you like it when real people make “cameo appearances” in novels that are otherwise fictional? It’s not a historical novel but I remember being a bit thrown recently when a pre-presidential Barack Obama makes a brief walk-on appearance in Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue. And you do see this a lot in historical novels — I don’t mean the kind that are actually about real people, like Philippa Gregory’s Tudor novels, but novels that are about fictional people in a historical setting, and suddenly there’s a glimpse of Samuel Pepys across the pub scribbling in his diary, or whatnot. My current novel is going to include appearances by less well-known historical characters, like Jessie Ohman who I portrayed so brilliantly in the video above, but also by people who are relatively famous in Newfoundland, like William Coaker and Wilfred Grenfell. I’d love to know how readers feel about real historical characters showing up in otherwise fictional stories!

April 1, 2013

The March Book Round-Up

Here’s my overview of all the books I read in March. My Lenten non-fiction reading list was significantly shorter this year than usual, probably because I devoted so much time and mental energy to one very long book, but I read some real gems along the way.

March 29, 2013

Crucified?

Good Friday. The day we Christians focus on the crucifixion of Jesus and the cost of sin.

Today, perhaps irreverently, I’m thinking about the way we lightly toss around the word “crucified” in other contexts. Like the person who brings an unpopular proposal to the staff meeting and “they totally crucified her over that!” Meaning, they disagreed with her idea and may have even mocked it a little. Crucifixion-lite, as it were.

We use it a little more seriously when we think someone is being “martyred,” even if not in the literal death-and-torture sense, for taking a stand we believe is admirable.

Which brings me to a current event of some interest to me: was Pastor Ryan Bell of Hollywood Adventist Church in any sense “crucified” by the Southern California Conference or by the Seventh-day Adventist denomination?

I’ve long been an admirer (from afar: I’ve never met him or attended his church) of Ryan Bell, whose ministry at Hollywood Adventist has focused on social justice, equality, creativity, and raising tough questions. On days when I feel oppressed by the conservative flavor of my own congregation I like to read Ryan Bell’s blogs and imagine I could attend that kind of Adventist church, with that kind of pastor. His ministry has given me hope and inspiration and expanded my vision of what’s possible within Adventism.

But I’ve also found myself wondering, how far will the institutional church allow Ryan Bell to go in exploring the far-left boundaries of “progressive Adventism” without subjecting him to church discipline? Now, I guess, we know the answer. This open letter appeared on Pastor Bell’s blog this week, explaining the reasons why he would no longer be serving as a pastor in the Seventh-day Adventist church.

I’m sad about this. I’m sad that a voice that represents some of the most extreme liberal views possible within our denomination has now been placed outside (even as some who express equally extreme conservative views are allowed to continue preaching and teaching). I believe there needs to be room in the church for a diversity of voices and that we need to be allowed to challenge each other. The question as always seems to be: how far is too far?

In the interests of balance, if you want an alternate point of view from someone who is quite happy to see the end of Ryan Bell’s ministry, you could read this article. It focuses primarily on a sermon by Trisha Famisaran, a guest speaker at Hollywood Adventist Church, and is, among other things, a shining example of how not to speak with respect and Christian love about those with whom you disagree. In this author’s view at least, Famisaran’s sermon was a key factor in bringing about the end of Bell’s ministry. While I don’t know whether there’s any truth to this, I do know that out of all the controversial views Ryan Bell is on record as holding, outspoken support for the LGBT community is one of the surest ways to get censured in the Adventist church at the moment (and in many other churches. While I’m talking about a specifically SDA situation here, the motif of outspoken leaders being disciplined by hierarchy is hardly unique to Adventists — Catholic friends may want to think here of the Vatican trying to rein in opinionated American nuns, for example).

But despite my sorrow, I must admit I don’t feel the outraged shock I see some people expressing about Ryan Bell’s dismissal. If I, as someone who followed his ministry with interest from a distance, saw this coming, I have no doubt that he and the members of his congregation saw it coming much more clearly.

Compared to other very conservative Christian groups, Seventh-day Adventists allow a surprising degree of diversity within our ranks – even among pastors and others in leadership positions. But everyone is aware that boundaries exist, and leaders – whether on the extremely liberal or on the extremely conservative ends of the denomination – are aware when they are pushing the boundaries.

I’m undecided as to whether there should even be boundaries. You may recall that in my ongoing video dialogue with Ed Dickerson a few weeks ago, he introduced the concept of “testing truths.” Misunderstanding what he meant by that term, I countered that maybe we don’t need “testing truths” – which I interpreted as the doctrines we use to define who’s “in” and who’s “out.”

My next Searching Sabbath video will be about the doctrine of “The Church” and I’ll be addressing some of these questions. (UPDATE: due to technical difficulties with YouTube I may not have this week’s Searching Sabbath posted on Sabbath. But it’ll be up soon). For now I’ll say that whether or not boundaries should exist, they do. Change happens when people are courageous enough to violate those boundaries. But anyone who does that is also aware (unless they’re unbelievably naïve) that boundary-pushing comes with risks. Genuine crucifixion is rare these days, but job loss, ostracism, and sometimes even loss of membership still occur all too frequently.

I’ve been wondering as I work my way through this series on the 28 Fundamental Beliefs, how much deviation, how much questioning, is really possible within the framework of faithful membership in a church. I was very heartened to read the following quote from an article by Andy Nash in the Adventist Review, our church’s official magazine, recently:

In the Adventist Church’s earliest days, there was no creed but Scripture; the only litmus test was the final authority of the Word of God. It should be no different today—as long as someone continues to prayerfully plumb the depths of Scripture, there should be room for them in this church. (Read the full article here).

I hope so much that this is true and continues to be true, for amidst all my doubts and questions I am always prayerfully plumbing the depths of Scripture, and doing it within an Adventist context. However, the irony of reading this quote in the same week when I learned about Ryan Bell’s dismissal is not lost on me. It’s true that the church generally demands a higher standard of obedience and conformity from leaders than it does from ordinary members. – perhaps rightly so? I’m not sure. I only know that despite the wonderful years I spend teaching at Kingsway College, Parkview Adventist Academy, and the St. John’s Adventist Academy, I was relieved when I stopped working for the church, because I felt I could more honestly explore and express my own questions, doubts and opinions without worrying about how I reflected on the institution I was representing – or how that institution would view me.

So these days, I pursue my “faithful doubter” journey from the perspective of an ordinary pew-sitter, and I take encouragement from people like Ryan Bell and Trisha Famisaran and others who are prepared to use positions of church leadership and denominational employment to challenge norms and ask difficult questions.

As for being “crucified” for your beliefs – metaphorically, of course – anyone within an organization who takes on that role of challenge, question, and advocating change, has to be prepared for the day the organization will reinforce its boundary lines and say, “You’ve gone too far … our definition of who we are as a people can no longer stretch wide enough to include you.” Even if you are continuing to “prayerfully plumb the depths of Scripture.”

It’s not really crucifixion, but it does hurt. And maybe it’s inevitable, human nature and human organizations being what they are. I wish it weren’t. What kind of world would we have to live in – what kind of church would we have to be – for that to be possible? I don’t know. But as I reflect on the meaning of Christian faith this Easter weekend, and as I plan my vlog and blog for tomorrow on the topic of “The Church,” I can’t help asking the question.

March 27, 2013

Writing Wednesday 26: Progress Report

This week’s video is not very fancy. No cool location shots or interesting theme … just an update on where I am with the book. Spoiler: I’ve finally finished editing what I wrote in November, and now the first half of the book is leaner, meaner and cleaner. And I’m excited about my Easter Break starting at the end of this week so I can get a good start made on the next part of the book.

That’s all for now, folks!

March 24, 2013

Sunday Supplement 03: Usher-ing In

In Ed Dickerson’s latest reply to my questions about Genesis, he goes into some detail about the genealogies and Genesis and argues that their purpose is not to establish the age of the earth.

Ed goes into this in more detail in another of his Grounds for Belief videos which you can watch here, pre-emptively answering some of my questions (although I still think that even if you allow for gaps in the chronology, inserting a gap between Noah and Shem, or anywhere else, is not going to get you anything like the timescale you need to line up with the existing evidence about human origins).

Anyway, here’s my latest reply:

March 23, 2013

Searching Sabbath 10: The Experience of Salvation

This week’s video, as always, is both longer and shorter than I’d like it to be. When I started this Searching Sabbath series, I wanted to keep the videos to about a 3 minute length, obviously overestimating my ability to be concise, which has never been my strong point. Instead, they’ve generally exceeded five minutes, which I think exceeds most people’s YouTube attention spans. This one is no different. But it’s also shorter than I’d like because, as always, there’s so much more to say about the topic of “salvation” than what I can cover in a short video.

In the video, I touched mostly on a question that I think is of great concern within the Adventist church and other evangelical churches: is the message of “salvation” relevant to the people we’re trying to reach? Speaking, that is, from the perspective of the twenty-first century church in North America. If what we are offering is “salvation from sin” and most people don’t have a sense that they are “sinners,” are we connecting? And if not, is the solution to try to make people more aware of sin — i.e. to induce guilt? — or to find out what people really do feel a need for in their lives?

However, there are whole other huge swathes of the idea of “salvation” that I haven’t touched on. One of these is: Do people really need salvation? Is sin, or the sense of being separated from God, really a problem that needs to be solved?

I guess that with all my doubts and questions, this is one of the places where I come down most firmly on the side of traditional evangelical Christian doctrine, because I don’t see how anyone can look at this world and say, “Everything is as it should be.” Something has gone sadly wrong, and all our best attempts have not fixed it. Or rather, we’ve fixed some things while at the same time making other things worse.

This, by the way, is also where I have a problem with a purely evolutionary view of human origins that denies we were created in the image of God or that we ever “fell.” As I see it, sin=selfishness. Nearly all the problems in any society anywhere on earth (barring natural disasters) can be put down to people doing things for selfish reasons that hurt themselves or others. From a purely evolutionary standpoint, there’s no reason this should happen. Evolution rewards selfishness in some cases (striving to stay alive and pass on your genes) and rewards altruism in some cases, where it’s obviously for the greater good of the species (i.e. mothers sacrificing themselves to save their children makes good evolutionary sense).

So, if we were a species that had simply evolved, we should see humans making decisions that would benefit the survival of the species. But in fact what we see is humans sometimes showing incredible selfishness (i.e. “sin”) even if the results are demonstrably bad for them and for the species. A species that had evolved naturally would not, I think, have developed the level of knowledge and technology that our species has done, and then use that knowledge and technology to make the planet unliveable for future generations of our own species. Obviously all the data is not in yet, but it seems as humans that we may be in the process of doing just that which, if true, is obviously sinful. I don’t think (correct me if I’m wrong, experts!) animals making selfish, short-sighted decisions that result in their own suffering and death and the possible elimination of their species. Animals, guided by instinct, act in ways that preserve themselves and their species. Humans, guided by reason, often act against our own and our species’ best interest.

The flip side, of course, is that we humans can be stunningly altruistic, even when there’s no benefit for ourselves in it. In my view, the way humans act is far more consistent with a species created in the image of God but fallen into sin, than with a species that has evolved and is evolving. Of course, that’s just the way I read the data, and there are other ways to interpret the human experience. But in general I come down on the side of the traditional view: we are sinners in need of redemption.

Most of my non-Christian (and even my more liberal-Christian) friends will be uncomfortable, I think, with the language of evangelicalism I’m using here in this blog and vlog. I think we evangelical Christians hugely underestimate how offensive our efforts to “evangelize” (that is, to convince others of the truth of what we believe) are to the majority of our neighbours and co-workers. There’s an assumed superiority in evangelical Christianity that people of other religions and no religion at all deeply (and understandably) resent.

So, do I believe in evangelizing? Not in the sense that I want to browbeat anyone into agreeing with the way I see God and the universe. On the other hand, if my faith “works” for me, if it gives me a sense of love, purpose and one-ness with God, why would I not want to share that with you? Particularly if you appear to be in need of it. My kind of evangelism is much too low-key for most Adventists. If you have your own beliefs and seem to be content with them (whether they are religious or non-religious), I’m not going to bother you with mine (particularly as I don’t believe you’re at risk of burning forever in hell … more on that later). If you ask about my beliefs I’ll do my best to explain them and discuss them with you, but I won’t go the further step of trying to convince you — partly out of respect and partly because I think it’s pointless anyway. Any “evangelizing” I do is more in the realm of giving information and trying to live in such a way that people will think better, rather than worse, of Christians and of Seventh-day Adventists based on what they’ve seen in my life. But if someone comes to me with genuine need and wants to know what I believe and how it applies to the need they feel in their life at that moment, I’m not going to refrain from telling them that I believe God loves them and Jesus saves.

As always, I’d love to know what others think about sin, salvation, and sharing our faith.

March 20, 2013

Writing Wednesday 25: Q & A

Well, there’s nothing particularly profound to say about today’s episode except that it features me answering a bunch of questions (seven, I think) in honour of it being my 25th vlog. I solicited questions from people on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter (and here on the blog, but nobody posted any here) and they covered a wide range of topics from the advantages of traditional publishing vs self-publishing to what books I read to my kids when they were small. Thanks to all who sent me questions … Enjoy!