Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 6

April 29, 2025

Everything is Tuberculosis, by John Green

If, like me, you’re a fan of John Green’s social media presence on the YouTube channel and podcast he shares with his brother Hank (Vlogbrothers; Dear Hank and John) won’t be surprised by the content of his new book, Everything is Tuberculosis. Green, who was already deeply committed to supporting local health care initiatives in African countries (specifically, supporting and raising funds for a maternal health care centre in Sierra Leone) became interested in tuberculosis while visiting Sierra Leone. Showcasing the same ability to take deep dives into subjects that he demonstrated in his essay collection The Anthropocene Reviewed, he began to learn as much as he could about the history of this disease, and how it can still be killing so many people every year when reliable cures have existed for decades.

The answer is, of course, injustice. As John Green points out repeatedly in this book, tuberculosis travels along trails humans have blazed for it, continuing to run rampant in poorer countries while being virtually eradicated in rich countries. he tells this story in an entertaining way, with lots of anecdotes about how everything from cowboy hats to Adirondack chairs can trace their history back to tuberculosis. Between the facts, the history, and the passionate argument that we can in fact do better, the linking thread tying this book together is the story of a young man named Henry Reider, a tuberculosis patient Green got to know in Sierra Leone.

The trick of this book is making the subject of tuberculosis both intriguing enough and personal enough to make people care about it. This book hitting bookstore shelves just as the US massively slashes its foreign aid budget, almost guaranteeing the fight against TB will move backwards instead of forward, is certainly something John Green could not have predicted when he started writing this. But it means the message of Everything is Tuberculosis is more important than ever right now.

April 28, 2025

Lady Tan’s Circle of Women, by Lisa See

Once again, as with Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Lisa See takes us into the world of Chinese women’s history, a cloistered world circumscribed by strict rules of social class, family structure, and protocol. This novel takes us several hundred years earlier, into the Ming Dynasty (what we’d call medieval times in European history; the subject of this novel, a real woman named Tan Yunxian, lived from 1461–1554). Lady Tan was known as a “woman doctor,” and this novel stitches together the little that is known about her life with Lisa See’s strong research into women’s lives in that period, to create a picture of how a woman could have gotten, and been able to use, an education in medicine. This was a fascinating glance into a little-known world.

On the Hippie Trail, by Rick Steeves

This was a fun, quick audiobook listen — travel writer and presented Rick Steeves reading (unedited) the journal he kept in his early 20s when he and a friend went on Rick’s first major trip outside Europe. It was the late 70s, just before the Iranian revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, when, as long as you didn’t mind being uncomfortable, you could take a bus all the way to India — and lots of young Americans did. This is definitely a snapshot of a moment in time — Rick points out in the intro that he didn’t edit his youthful journals to try to smooth over some of his views at the time, and you definitely get the sense that he would not have used some of the same descriptors and stereotypes today as he did then when encountering people from different cultures. But even with his admittedly limited perspective at the time, you can already see in him an openness to people and experiences that would go on to make him a great travel writer. Knowing that that “hippie trail” journey would shortly become impossible due to political upheavals in the region adds to the feeling that this journal captures a fleeting slice of life that can’t be revisited, anymore than our own youth (much less adventurous than Rick Steeves’s youth, for most of us) can.

March 24, 2025

Circle of Hope, by Eliza Griswold

This was a really interesting book. Journalist Eliza Griswold spent several years researching and interviewing people involved in a progressive evangelical church called “Circle of Hope.” Initially, she intended the project to be about shedding light on a little-understood corner of American Christianity — people who hold to most of the key tenets of evangelical Christianity, but who, rather than embracing Christian nationalism and right-wing politics as so many conservative Christians have done, instead tend to lean either generally to the left, or to remain determinedly apolitical. (Circle of Hope, specifically, is in the Anabaptist tradition, so their position was always to be beyond politics and not get caught up in political divisions).

However, as the Covid-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement unfolded in 2020, and the church’s founders took a step back to make way for new leadership, Griswold found herself chronicling something else entirely: how a progressive community founded on ideals of love, mutual help, and social justice, essentially imploded and fell apart.

It’s a sad and very human story that feels extremely relevant to those of us who go to church, but also to people involved more generally in collective endeavours, especially of the doing-good kind — a lot of the thing that happened at Circle will sound familiar to anyone who has worked or volunteered in the non-profit sector, including a pretty significant case of founders’ syndrome from the pastoral couple who were supposed to be stepping back from leadership.

There’s no shocking sexual-abuse or money-embezzling scandal here, and most of the issues the divided Circle’s four pastors and their congregations weren’t even theological. The decision over whether to fully affirm LGBTQ members created some fault lines, but for the most part, members and leaders remaining generally on the same Anabaptist page, theologically speaking. Where they divided was over how to do what they saw themselves called to do — represent God and live out God’s love in the world. For some, this involved making anti-racism a key part of their mission, while others felt that it was enough just to not be overtly racist, and that there were other issues just as important as racism.

What ends up happening, as pretty much anyone who’s ever been part of a human institution can tell you, is that it quickly stops being about ideas and ideals and becomes about personalities — particularly the personalities of the four current pastors and the semi-retired founders. Griswold tells the story from each of the pastors’ perspectives, based on extensive interviews and extended periods of time immersed in the four congregations, observing how well-meaning conflicts over how best to share God’s love with neighbours devolved into accusations, sniping, and recriminations.

There are no clear moral-of-the-story lessons here, no guidebook for how churches or other organizations might avoid the kind of unravelling that happened at Circle of Hope. Rather, Griswold simply invites the reader to do what she did for four years — observe, listen, empathize with people on all sides of this conflict, and decide for ourselves what messages we can take away from this sad tale of well-meaning people trying to do God’s work, and letting human nature get in the way.

March 23, 2025

The Murderbot series, by Martha Wells

I’ve been reading through this series off and on for the past year and just now finished System Collapse, the latest book. This series is much more “hard sci-fi” and tech-centric than what I usually read when I wander in to the sci-fi genre, but it has such great writing and such an appealing main character that I’m able to get past the fact that there are whole swathes of chapters where I’m not sure what exactly is happening in the plot because I’m not able to keep up with all the techie details.

The main character is the titular Murderbot — a nickname it’s given itself — a human-like robot with a mix of machine and organic parts, designed to operate as a Security Unit — much tougher than a human security guard, and programmed only to obey the instructions of whoever has paid for its use. However, Murderbot figured out how to disable its governor module so that it’s able to think independently and make choices. It no longer has to do whatever it’s told.

So then, of course, it has to figure out what to do.

Murderbot lives in a futuristic world with lots of space ships and space stations and planets and while it’s not exactly dystopian, it’s not great either. Humans don’t appear to live on earth anymore in this version of the future, and most of the human-colonized planets and the space stations they live on are kind of a capitalist hellscape, where corporations rule everything, employ slave labour, and can pretty much do whatever they want. There are a few human societies that live outside the “Corporation Rim” and defy those values, and it’s a group of those humans that Murderbot is contracted to provide security for on a mission when the first book opens.

I’ve long felt that there are basically two story paths for bot/droid/etc characters in science fiction: there are characters like Data in Star Trek: Next Generation, who admire humanity and want to become more human, and then there are bots and droids who look down on humans and don’t want to be like them in any way (the best example I can think of in this category is not really a good example: it’s Seven of Nine from Star Trek: Voyager, who of course actually is human by birth, but becomes assimilated into the Borg and then rescued back into a human society that, for much of her story arc, she really doesn’t want to reenter).

Murderbot is more like the second category, in that it doesn’t exactly despite humans, but it finds them strange and difficult to deal with. Even more difficult to deal with is the fact that now that it has free will, Murderbot has to, in some ways, learn to think the way a human does — to decide what to do with its choices. This is really the story arc of this whole series — the wonderfully cynical, snarky, detached Murderbot coming to terms with having choices, having emotions, even having relationships (both with humans and with non-human intelligences — but by “relationships” please don’t think I mean sexual relations, because, ugh, nothing would gross Murderbot out more!).

All the best speculative fiction, for me, really centres around the question “What does it mean to be human?” This series, about a character who is quite determinedly not human, is one of the best explorations of that question I’ve ever seen.

There’s also a TV series coming, and yes, I’ll watch it, although I’m skeptical television can capture the wonderful inner voice of Murderbot, which is the thing that makes the books such a pleasure. I guess we’ll see!

March 22, 2025

Last House, by Jessica Shattuck

Last House turned out not to be the kind of book I expected it to be, but I think it was better than the book I expected.

The blurb I read gave me the impression this was a multi-generational family story centred around a New England house — something like Bonnie Burnard’s A Good House or Anne Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread, or, in a rather different way, Daniel Mason’s North Woods.

This is sort of what Last House is, but not really. It begins a few years after the Second World War, when Nick and Bet Taylor and their two young children buy Last House, an idyllic and isolated retreat in the Vermont mountains, as a respite from their suburban lives. Nick, still coping with trauma from his wartime experiences, is a lawyer for oil companies and finds himself deeply involved with the efforts by big oil companies and the CIA to prop up the Shah’s regime in Iran to allow unfettered access to Iranian oil. Bet, who worked as a codebreaker in Washington during the war, feels frustrated and constrained in her new role as housewife, though she adores her children Katherine and Harry. So far, it feels like a typical mid-century marriage-and-family saga, but Nick’s work in Iran is a tip-off that this novel is going to explore issues of politics, capitalism, war, human rights, and environmental devastation that flow, like oil, beneath the surface of what we can see.

It’s really only a two-generation story, and barely that — we get a glimpse of future generations at the very end, in a kind of epilogue chapter, but most of the story takes place in two acts: the first in the 1950s, the second in the 1970s. When the second act rolls around, Nick’s and Bet’s lives are much the same, but Katherine and Harry are in their late teens/early 20s now, and as young people of their era they get swept up in the counterculture in New York City, with their political involvement leading not only to inevitable conflict with their father who still works for Big Oil, but eventually to a shattering tragedy.

To me, this reads not so much “multigenerational family saga centred around a family house” — though that is part of it — but rather an indepth and thoughtful novel about how mid-20th-century American and international political issues play out against the backdrop of a single family, how young people are both shaped by and push back against the values of their parents. Every character in this family interested me, none of them were simple and none of their actions or reactions were as predictable as I’d originally thought they would be. There’s real complexity here (which does not surprise me in a Jessica Shattuck novel). The Iranian segments of the story were just as interesting to me as the Vermont and New York scenes, if not moreso, because they gave me an interesting perspective, from the point of view of a peripherally-involved American, on the events that led up to the Iranian Revolution, and the murky moral mess that precipitated it.

I enjoyed reading this a lot.

Long Island, by Colm Toibin

Over fifteen years ago when I read Colm Toibin’s novel Brooklyn, I was quite distracted by the fact that my own novel about immigrants coming to Brooklyn was being released that same year. I did manage to get past that enough to read Toibin’s novel and appreciate what a beautifully written, evocative book it was; my main critique of it (which was not really a critique, because it was absolutely intentional on Toibin’s part, just annoyed me) was the passivity of the main character, Eilis Lacey, the young woman who moves from a small town in Ireland to Brooklyn, New York in the 1950s.

This novel picks up twenty years later. Eilis is married to her Italian-American husband and they no longer live in New York; consistent with the fortunes of upwardly mobile (not to say “white flight”-ing) Brooklynites by the 1970s, the whole extended family has now moved to Long Island, where they live in four houses next to each other on a cul-de-sac and experience a little more family togetherness than Eilis, who has never really felt part of the clan, is comfortable with.

Eilis’s children are in their late teens, almost ready to launch into independence, and with her home, her marriage, and her job as bookkeeper for a neighbour’s small business, she seems to be in a manageable if not thrilling routine. Then she learns something that shakes her marriage, and by extension her whole Long Island life, to its foundations.

I appreciated seeing that on receiving this news, Eilis shows she is a much less passive woman than she was in Brooklyn (or in Brooklyn, I guess). Her response to the crisis is very firm and very decisive, and never wavers. On the heels of this upheaval, she packs up and returns on an extended visit to her aging mother in Ireland, inviting her teenage children (but definitely not her husband) to join her later in the summer for their grandmother’s eightieth birthday party.

The novel is told from three points of view: Eilis herself; Jim Farrell, the man she was seeing back in Ireland before she got married; and Nancy Sheridan, who was Eilis’s best friend back home with whom she’s lost touch. As events both in Ireland and back in Brooklyn move towards inevitable conflict, my sympathies shifted among the characters and my perception of them as people changed quite a bit. The story ends very abruptly — whether because there is going to be a third Eilis Lacey book, or because we are left to draw our own conclusions about how things get resolved … well, that remains to be seen, I guess.

The Poppy War, by R.F. Kuang

This book, the first of a trilogy, started so well that I was sure I was going to want to race through the whole trilogy as quickly as possible. Yet by the time I finished it, I had absolutely no desire to pick up the sequel. It’s not badly written at all, it’s just very definitively Not For Me. This is OK, I’ve realized. Not all books are for all readers.

The Poppy War, as the title might suggest, is a fantasy novel set in a world inspired by China — the events of the novel corresponding quite closely to late 19th-early 20th century China, though the setting in the book is pre-industrial and the weaponry medieval, as is typical for fantasy novels. A young orphaned girl, Rin, takes a desperate long shot at escaping her miserable life by taking the famously difficult entrance exam that will grant her admission to higher learning, even though she has no formal education. It’ll be no surprise to anyone who’s ever read a fantasy novel that Rin passes the exam, gains admission to an elite military academy, and finds herself a fish out of water among her wealthy, privileged classmates as she tries to harness her natural talents to become a warrior.

So far, so familiar — but not in a bad way. These are the tropes of much fantasy, and if well executed, the story of the kid from nowhere who turns out to have special gifts and carves out their place in the world can be an enjoyable journey. “Enjoyable” isn’t quite the word here, as one hardship after another befalls Rin in her education to the point that the novel began to remind me of Elizabeth Moon’s The Deed of Paksennarion, an epic fantasy novel I read in the years before I blogged about everything I read, in which the heroine joins a mercenary company and goes through so many trials and tribulations I got exhausted reading about them and never had the urge to re-read the novel (which is unusual for me).

However, the Chinese-inspired setting of The Poppy War was interesting and well-drawn, and Rin was an engaging character who I wanted to succeed, so I hung in there.

Then it got worse.

Then it got much, much worse.

Not only the amount of suffering our heroine has to endure, nor even the staggering amount of much-too-vividly described suffering she sees around her (it is set during a brutal war, after all), but the suffering she becomes willing to inflict, the evil she herself is willing to commit — all I can say is, it just got too dark for me. To the point where it felt unrelenting and gratuitous, and I had no hope that Rin would continue to be a character whose adventures I wanted to follow through two more books.

I’ve seen this book described as “grimdark” which is just the kind of cheeky BookTok-trope-inspired descriptor that I usually don’t use, but it is both very, very grim and very, very dark. And that is fine if that’s the kind of thing you like to read. I personally like my fantasy with lots of realistic darkness and drama, but also with an overarching sense that there is good in the world worth fighting for (thank you, Professor Tolkein, for pre-setting my expectations that way) and also that the story’s main character, while they may be deeply flawed and do bad things, is ultimately on the side of that good and will help to bring it about. Call me old-fashioned but those are the kind of fantasy novels I like.

Fortunately, there are lots of those kinds of books. And for people who prefer grimness, darkness, an overarching lack of hope, and an antihero you may not be able to cheer for … there is The Poppy War. And its two sequels, presumably … though I’ll never know for sure.

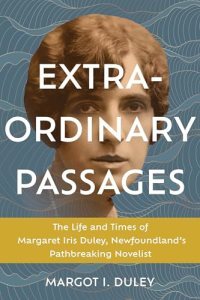

Extraordinary Passages, by Margot I. Duley

Extraordinary Passages is the first complete study of the life and work of Newfoundland’s first significant novelist, Margaret Iris Duley (1894-1968), written by her niece, historian Dr. Margot Duley. This book is an important contribution to the literary and academic culture of Newfoundland and Labrador; many of us know that Margaret Duley was the first Newfoundlander to have her critically acclaimed novels published in Canada, the US, and the UK, but may not know a great deal about her life or even about the contents of those novels.

This book is my favourite kind of non-fiction: a book written by a scholar, with an academic’s thoughtful care for accuracy, detail, and sources, with copious footnotes and a useful index — but written in lively and accessible language that can be appreciated by a non-academic reader. The fact that the writer is the author’s niece adds another level of depth to this study. While Margot Duley writes with detachment and, where necessary, with a critical eye about Margaret Duley, there are places in the book — especially in dealing with Margaret’s family relationships in later years, when Margot was growing up — where an element of memoir is woven into the biography. Margot Duley does not hold back from sharing her warm personal memories of her aunt, and for me this enriched the book.

Margaret Duley’s life spanned much of Newfoundland’s turbulent twentieth century: two world wars, the Depression, the women’s suffrage movement, the Commission of Government years, Confederation and the changes that came in its wake, all impacted her, and this book not only shows us Duley as a person and a writer, but situates her in her historical, social, and political context. This book is both important and tremendously enjoyable, and it makes me want to read more of Margaret Duley’s novels.

The Crane, by Monica Kidd

Tolstoy allegedly said (or perhaps didn’t say; it’s unclear) that there are only two stories: a man goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town.

Of course, those are actually the same story. If a man (or a woman, which apparently didn’t occur to Tolstoy) goes on a journey, then wherever he goes, he arrives as the stranger in town. So maybe there’s only one story.

All of which is to say that Monica Kidd’s beautiful new novel starts with a stranger arriving in town. It’s 1969, and a young American man named James is arriving by train in St. John’s, Newfoundland, a city where he knows nobody and nothing awaits him. Also, he’s broken his glasses, meaning that he arrives in town with a level of vulnerability that I found immediately relatable.

If you’re at all versed in North American 20th century history, you might already (even without the back cover blurb) have a good guess as to why a young American might be arriving alone in a Canadian city in 1969. And yes, James is what was called then a “draft dodger” — escaping the US to avoid being drafted into the military and sent to Vietnam. There’s a backstory behind why he chooses such a remote corner of Canada to retreat to, and as that story unfolds in flashback scenes we learn more about why this particular man is on this particular journey.

James is a quietly engaging character, with a very low-key, self-deprecating sense of humour and a lot of regrets about how things have already unfolded in his short life. He’s carrying a tremendous amount of grief, and the quest that brings him to Newfoundland is a way of trying to bring some closure to the biggest loss of his life. When he goes on yet another journey — travelling from St. John’s to a small outport — he discovers that closure is not as straightforward as it seems.

I said James is a “quietly engaging” character, and “quiet” is the adjective that comes to mind most often as I think back on this book. I mean that in a good way. Sometimes people say a book is “quiet” in a way that implies it’s not vivid or interesting, and that couldn’t be farther from the truth. Both the author and the main character have a kind of control in this story that keeps the reader’s focus on this single story unfolding against the background of much bigger events. James’s home country is torn apart by the Vietnam War and the anti-war protests, both on a national level and on the very personal level of James’s family. In the place he chooses to escape to, Newfoundland, the war seems very far away — but twenty years after Confederation, Newfoundland is going through its own changes, the old way of life falling away in ways that are not always easy or welcome.

Yet against these huge societal tides, we travel along with James on this small and specific journey: into the heart of loss and the task of finding a path through it. James’s travels bring him from one community dealing with loss to another, on the other side of the continent. If James finds the catharsis and healing in Newfoundland that he couldn’t find at home, that’s not to say that Newfoundland is a better or more mentally healthy place than Wyoming, but rather that sometimes, a person just has to go on a journey.

I loved reading this book. I’ve also rarely read a book where I’ve wished more at the end that there was a time-jump forward epilogue — I had clear ideas about where I wanted to see James and some of the other characters end up in a few years — but on reflection I was OK with the author leaving that denouement to my imagination.

This is a beautiful, quiet, thoughtful story about loss, leaving, and finding yourself somewhere far from home.