Trudy J. Morgan-Cole's Blog, page 5

June 2, 2025

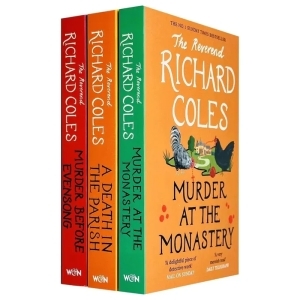

The Canon Clement Mysteries, by the Reverend Richard Coles

I was eager to pick up a copy of Murder Before Evensong which I was in England, since it’s not so easy to get over here and, knowing a little of Reverend Richard Coles’s work, I was interested to see what he’d do with a cozy mystery centred around an Anglican priest. I enjoyed it enough that I picked up the other two volumes and will likely read the one coming out soon if I can get it here in Canada.

These are a really enjoyable read even if they have some flaws. A big one is that it becomes quite evident as the story goes on that what Coles really wants is to write a series of novels about being an Anglican priest in a small English village in the late 1980s. You can do just this – think of Jan Karon’s “Mitford” novels, about an Episcopalian priest in the rural US, which lean very heavily on setting and character with only the barest hint at plot. Think, too, about my own favourite Lindchester Chroncles by Catherine Fox, about the community of clergy and lay people around a modern-day English cathedral. But such novels combining a gentle slice of life with a good dose of spirituality are rare, and I can easily see why Coles felt that adding in a murder to each book would make them more marketable.

Each book is about 400 pages, and in none of them does the body show up much before page 100 — even when it does, the solving of the murder often feels secondary to village gossip and Canon Clement’s own personal conflicts. So if you really want the mystery to be absolutely central to the mystery novel, you may find these frustrating. But if what you really want to read about is, say, being a Anglican priest in an English village in the late 1980s, these could be right up your alley.

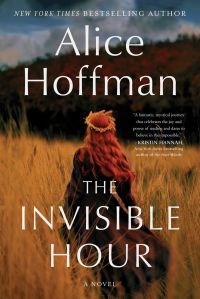

The Invisible Hour, by Alice Hoffman

This is the second book I’ve read this year that imagines Nathaniel Hawthorne as an irresistible romantic hero, and frankly, I had trouble buying it in both cases. I re-read The Scarlet Letter in preparation for reading Laurie Lico Albanese’s Hester, so it was fresh in my mind when I came to The Invisible Hour, a novel about a young woman who grows up in a restrictive fundamentalist cult/commune and finds in classic novels, especially The Scarlet Letter, her only escape. I wasn’t entirely prepared for this novel to take a time-travelling twist, and even less prepared, as I said, for the entrance of Sexy Nathaniel Hawthorne for the second time in my reading year. While I loved the last Alice Hoffman novel I read — The World That We Knew — this one didn’t grab me in the same way at all.

June 1, 2025

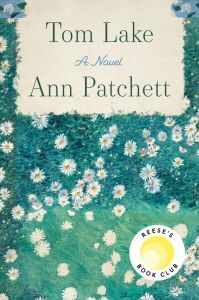

Tom Lake, by Ann Patchett

This novel is told in two parallel timelines. In the story’s present day, it’s spring/summer 2020, and Laura and her husband Joe are enjoying having their three twenty-something daughters home while the world shuts down. It’s quality family time, but it’s also a hard-working time, because the family owns a cherry farm, and with quarantine regulations making it impossible for them to hire their usual seasonal pickers, everyone has to pitch in to get the cherries picked.

While they work, over a period of days and weeks, the young women urge their mother to tell them the full story of the time when, as a young aspiring actress, she had a brief affair with a fellow actor who went on to become a genuine movie star. Laura’s eldest daughter went through a teenage phase of being completely obsessed with actor Peter Duke and, knowing that her mother had briefly dated him, became convinced that Peter Duke was her real father. While Laura has pointed out that the timeline of the relationship, and of her marriage to Joe, doesn’t make that possible at all, the girls want to know the details.

So the present-day story of Laura and her daughters in the pandemic stillness of the cherry orchard unfolds alongside the story of young Laura, who got into acting through a single starring role in high school — Emily in Our Town — and returned to that role, after a brief stint in Hollywood, for a summer theatre festival where she starred alongside up-and-coming actor Peter Duke. The story of their love affair, and of Laura’s exploration of what she really wants out of life, makes a neat coming of age story.

I was interested to read in the Afterward that for Ann Patchett, as for Laura in the book, the play Our Town is a foundational text, because it is for me too, and in the oddest way imaginable. It’s had a bigger influence on me than any other play (and is top five in works of literature that have impacted me, generally), but I have never seen it on stage. The impact grew entirely out of reading the play (I don’t usually read plays!) during my college years, and being deeply touched by the idea of Emily coming back from the dead to relive one very ordinary day in her childhood. The concept that any ordinary, boring day is a day we would be thrilled to go back to if it were all taken away from us — that so many of us miss the magic of the everyday — has profoundly shaped the way I view the world.

While this scene, unlike many others in the play, doesn’t get directly quoted or referenced in the novel, I feel like the very ordinariness of Laura’s life after she stops pursuing an acting career is a tribute to Emily’s discovery in the play. Laura chose an ordinary life instead of the madcap roller coaster of Hollywood drama that she could have had with a series of men like Peter Duke, and the richness and beauty of the life she chose permeates the novel.

I really, really enjoyed reading this book.

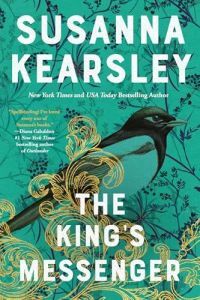

The King’s Messenger, by Susanna Kearsley

I’ve known about the existence of my fellow Canadian historical fiction writer Susanna Kearsley for years before I read anything by her. I learned of her in the oddest way. While Kearsley writes historical novels under her own name, she also writes thrillers under the pen name “Emma Cole.” That’s right, the same name as my talented daughter (real name: Emma Cole). When my Emma found out as a teenaged aspiring writer that there was already a writer using her name as a pen name, she of course pointed this out to me with a little mock-outrage that someone had “stolen” her name!

None of this has anything really to do with Susanna Kearsley and her book The King’s Messenger; it’s just how I became aware that she existed. I’m unlikely to ever read one of her Emma Cole books, since I’m not a thriller-reader, but her historical fiction — including this latest book set in the court of King James I/IV of England and Scotland — is right up my alley.

The titular King’s Messenger — an official role for men whose position at court involved, essentially, going on messages for the king (does what it says on the tin!) — is a young Scotsman called Andrew Logan, who is sent on a mission that tests his loyalties, as he is dispatched to arrest and bring to justice a man who he increasingly comes to believe is not guilty of the crime about which is to be interrogated – the murder of the recently-deceased Prince Henry, heir to the throne.

Kearsley deftly weaves her fictional characters into the real history of King James’s court, with an engaging love story as a bonus. I enjoyed this book and would definitely read another by Kearsley.

Field Notes for the Wilderness, by Sarah Bessey

Sarah Bessey’s writing appeals to me for the same reason that it sometimes slightly disappoints me: she has struggled with, and thought through, many of the same issues that I have. Which is great, but it does mean that sometimes what she is revealing as her own hard-won learning strikes me as a bit of “well, I already knew that.” That was the case with her book Jesus Feminist, which I really liked when I read it about ten years ago — it spoke to me, but mostly in the way of confirming things I had already known and believed for a long time. Bessey writes for people who, like me, have their heritage and the beginning of their spiritual journey firmly planted in conservative Christian denominations, but who have either left those churches, or remained uneasily in them, loving things about their tradition but critical of leadership and of some teachings.

Field Notes for the Wilderness speaks to people in both these situations, assuring them that it’s OK for faith to grow and change throughout our lives (in fact, it’d be weird if it didn’t) while also acknowledging that these changes can be painful and involve real losses — loss of relationships, loss of community. Bessey doesn’t glibly assure readers that forging new relationship and community is easy — she recognizes that following your conscience can be a difficult path. There were times in this book when I wanted fewer words spent reassuring me that it’s OK to be on the journey I’m on — “I already know that!” — and more practical suggestions. But that reassurance is just what a lot of people need, people who are still questioning whether they might, after all, end up in an eternally burning hell they’re not sure they believe in, if they take steps outside the known boundaries of church teachings. I think those are the people that most need to read this book and be encouraged by Sarah’s wise and experienced voice.

Great Big Beautiful Life, by Emily Henry

Emily Henry is such a reliable writer. You know there’s going to be a young-but-not-cringingly-young couple, both connected to the world of books in some way (writer, editor, publisher, librarian, bookstore employee … you get it) who will go through the predictable romance tropes of meeting, attraction, obstacles, and eventual resolution with wit, charm, and a moderate degree of steaminess. And there will be a happy ending.

Great Big Beautiful Life is no exception. With an opening premise that reminiscent of Taylor Jenkins Reid’s The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, struggling journalist Alice is hired by a reclusive heiress who disappeared from the public eye decades ago, to write her biography.

Or at least, Alice is sort-of hired. Turns out she’s actually on trial, with the old lady meeting alternately with Alice and another writer, the much-more-successful Hayden, who’s already written one best-selling celebrity bio. Her plan is to allow both of them to interview her separately, then to decide who’ll get to write the book. Alice, who is smitten with the handsome but reserved Hayden almost as soon as they meet, is sure he’ll get the job — but she’ll also do everything she can to win this weird competition.

That’s the set-up, and of course the story goes exactly as you’d expect it to go. But what a great ride it is, and it includes some genuinely unpredictable twists and turns (at least, I didn’t see them coming). I had loads of fun reading this.

The Bandit Queens, by Parini Shroff

This book was recommended to me awhile ago and I finally got to read it. I usually really enjoy novels set in India, and this one has a great premise — a woman who is suspected of murdering her husband (she didn’t; he just disappeared) is approached by other women in the village who want help getting rid of their unwanted husbands also. It was a quick and engaging read, though it felt a little tonally off in some places — I guess it’s the kind of “dark humour” (there are actual deaths involved) where it can be hard to strike that balance between the humour and the darkness. The husbands certainly deserve it, as they are in some cases very abusive, but it still felt like the author was trying to walk a bit of a tightrope between an empowering comedy of sisterhood, and a darker tale about abuse and murder. I enjoyed reading this but I had reservations.

April 30, 2025

Conclave, by Robert Harris

Earlier this year, when everyone was talking about the movie Conclave, I realized it was based on a book by Robert Harris, a writer whose historical novels I love. This one isn’t historical; it’s quite contemporary — although in a way it feels like it could be historical, because the rites and rituals surrounding a papal conclave are so ancient that it feels like the cardinals at the centre of the story are living in the modern world and in medieval times simultaneously.

Harris always does excellent research, so I am sure he got most of the details of how a papal conclave works right, even though he takes liberties for fiction’s sake and of course the whole thing is so shrouded in secrecy there are details we may never be sure of the accuracy of. What feels so true to me (knowing a lot about religious people though nothing about Catholic cardinals specifically) is how the ambition, the jockeying for power, sits uneasily alongside what for most of these men is a deep a genuine faith. I’m not sure everyone writing about Vatican politics would get that right; I’m not sure if the movie (which I haven’t seen yet) conveys that. But I felt strongly that despite their flaws and the self-serving things some of them do, these men — especially the main character, Cardinal Lomelli — genuinely believe in the Church’s mission and desire to serve God, and are troubled by doubts and driven by faith, just like Christians in much humbler and less powerful positions who also sometimes do bad things in the course of trying to do God’s work.

I made a conscious decision when I first learned of both the book and the movie, to wait awhile to read them. Pope Francis was in poor health at the time, and, knowing he couldn’t last forever, I thought it would be interesting to read the book and watch the film in the period between the pope’s death and the selection of a new pope. While the pope who has just died in Conclave is never named, all the popes leading up to him are historically accurate up to Benedict/Ratzinger, and the dead pope is extremely similar to Francis in many biographical details. So this felt like a timely read in a way that was both sad and appropriate.

The Capital of Dreams, by Heather O’Neill

I think it might be time to admit that Heather O’Neill’s writing, while beautiful and highly acclaimed, is just not the best match for my brain. I admire the scope and ambition of her novels, but for me there’s always something lacking in engagement with the story and characters, and I think it’s just a question of writing style and reading style not syncing up, just as it was with Lullabies for Little Criminals and When We Lost Our Heads.

Like that latter book, The Capital of Dreams both is, and is not, a historical novel. It’s set in a fictional European (probably Eastern European) country called Elysium, at the beginning of a war that seems to be the Second World War, though “The Enemy” of the novel is never identified as German or Nazi. While Elysium is fictional and the Enemy is vague, there are references to real places (someone is living in Paris) so the mythic world is somewhat anchored within the real world. Elysium, a small country struggling to maintain both its political and its cultural independence, is invaded and occupied by the Enemy, and fourteen-year-old Sofia, daughter of an acclaimed Elysian writer who is more into being a writer than being a mother, is being sent away from the Capital (nameless, like the Enemy) to safety with a group of other children. So begins a picaresque journey through a war-torn countryside, in company with a talking goose: a meditation on war, motherhood, the power of art, and human cruelty. Interesting and well-written, but I wasn’t as emotionally engaged in the story as I would have liked to be.

The Lady’s Guide to Petticoats and Piracy; The Nobleman’s Guide to Scandal and Shipwrecks, by Mackenzi Lee

These two sequels pick up where The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue leaves off. Or rather, the Lady’s Guide picks up not too long afterwards, with Felicity (Monty’s sister from the first novel) desperately trying to figure out how to become a doctor at a time when women were banned from studying medicine, and ending up on a madcap voyage through Europe. The Nobleman’s Guide picks up the story twenty years later, when the baby sibling Monty and Felicity left behind has grown to young manhood and meets the siblings he never knew he had. This is perhaps the biggest flaw with the third novel: it has to happen twenty years later in order for Adrian to grow up, but Monty and Felicity don’t feel like people approaching or just past forty; their reactions, problems, and solutions are still those of the young people they were in the first two books.

Despite this, these are fun historical romps (with some deliberate anachronisms and the occasional touch of the paranormal) that continue to answer the question: how did people cope with supposedly “modern” issues (bisexuality, asexuality, feminism, mental illness, etc etc etc) at a time when all those things existed but without the understanding and language we currently have to talk about them. While the Montague siblings’ adventures often stretch credibility, they’re always fun journey and a little bit thought-provoking.