M.B. Zucker's Blog

August 9, 2025

Top 10 Biopics of all time

June 21, 2025

Adams and Eisenhower: Different Personas, Similar Visions

Speech, Technology, and Democracy

June 15, 2025

Top 10 Friendships between Presidents

January 12, 2025

"Swift Sword" book review

Author: Doyle Glass

Year of Publication: 2014, 2023 (second edition)

Swift Sword by Doyle Glass is a gripping and immersive account of the Quế Sơn Valley skirmish during the Vietnam War. Modeled after Eugene Sledge's classic memoir, With the Old Breed, Glass aims to provide a similar tribute to Vietnam veterans, and he succeeds admirably. The book tracks the intense and deadly combat between American forces and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) in meticulous detail.

This nonfiction novel is drawn from extensive interviews with Marine veterans, their loved ones, after-action reports, and firsthand accounts. One of Glass’ most insightful decisions is to italicize the veterans’ quotes while providing his own description and fictionalized dialogue to fill in missing gaps, enhance the drama and image, and maintain a novelistic pace. The result captures the complete event in its full externality, less a photograph than a panorama like the one in the Gettysburg Museum.

Glass provides personality flavors of the Marines and avoids deep character analysis as he roots his portayals in the veterans’ interviews, eschewing the psychological analysis in which some writers would indulge. Swift Sword instead makes the portrayal and study of the event its focus. The narrative is one of constant action as different Marine units react to enemy engagements. Every dimension of combat in Vietnam is portrayed, from a helicopter rescue to a chaplain handing out gas masks. There is also an interesting chapter toward the book’s conclusion that gives the North Vietnamese perspective. Glass explains that many of the communists battling the Marines were from the South, usually from Quế Sơn, but they believed in the North’s cause while feeling no loyalty to a Southern government they viewed as illegitimate and propped up by Washington.

This is an excellent book on the Vietnam War. It is perfect in fulfilling its intent, which is to give as complete a portrayal of combat in that conflict as though the reader had themself experienced it. It is narrow in focus but holistic in execution. Hemingway wrote that “All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened.” Operation Swift Sword did happen, but this account blends memory with narrative so as to become literary truth. It is highly recommended for Vietnam veterans or buffs and is an excellent representation of that war within the historical fiction genre.

December 17, 2023

Top 10 Foreign Policy Presidents, Number 1: Dwight Eisenhower

I know, I know, this is no surprise to anyone and half of you are probably accusing me of bias. But there are reasons why Ike is my political hero and his foreign policy is the main one. I credit him with stabilizing the nuclear age, the largest and complex achievement of any President and, in all likelihood, of any leader in world history.

(Image from The Spokesman)

He inherited the High Cold War from Truman, which included both the stalemated Korean War and a memorandum titled NSC 68. This document described the Soviet Union as an existential threat and recommended quadrupling the military budget which Truman authorized. Ike pulled from his career as an Army officer and leadership against Hitler to restructure America’s containment of communism.

The Great Equation was the core of Ike’s presidency and ideology. It linked the relationships between world peace, military spending, and the national debt. Ike wanted to further peace in part because he wanted to cut defense spending and balance the budget. These considerations played into his reevaluation of Cold War strategy in the fall of 1953. He believed Truman’s strategy of containing communism through limited wars like Korea was too costly to maintain for the long-term. He ordered Project Solarium, which saw three teams create Cold War strategies to replace Truman’s model. Team A, led by George Kennan, proposed containing communism through building alliances, primarily in Europe. Team B proposed threatening to use nuclear weapons to contain communism. Team C proposed rolling back communism wherever possible. Ike melded all three proposals into the New Look, which became his signature national security strategy. He expanded America’s nuclear arsenal and threatened a large-scale nuclear response (Massive Retaliation) against the communist world if the communists tried to expand anywhere. Ike, who led Operation Overlord and defeated Nazi Germany, was uniquely credible in making this threat. Once Ike effectively thwarted Soviet expansion he wanted to negotiate a reduction of nuclear weapons.

Ike used his poker skills to make his nuclear bluff credible. He wanted to make the Soviet government and American people believe he was serious. He intentionally sought to appear less than intelligent so others would believe that he did not understand the consequences of using nuclear weapons. He suggested there was no difference between nuclear weapons and bullets during a press conference. He pretended to misunderstand his translator when meeting with foreign leaders so they’d think he was dumb.

Ike was willing to let Americans fear the increased risk of nuclear war if it let him contain communism while cutting military spending. He played golf to seem uninterested in his presidential responsibilities. The purpose was to make the American people believe that the Cold War was not as dangerous as it seemed. Ike calmed the country’s anxieties, but this contributed to his reputation as a do-nothing president.

The New Look allowed Ike to cut military spending and balance the budget. He was able to cut conventional forces, which were more expensive than nuclear weapons. Reducing conventional forces also removed America’s abilities to fight limited wars like Korea. By removing the means to fight a limited war, he meant to eliminate the temptation to participate in limited warfare. Relying on nuclear weapons to contain communism, as opposed to conventional forces, allowed Ike to prevent any communist expansion for eight years without losing any American soldiers.

Shifting containment from conventional forces to a nuclear deterrent was much more affordable for the US and allowed the US to contain communism until the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. This means Ike was a major architect of the West’s victory in the Cold War.

Massive Retaliation was an enormous gamble. Ike needed to convince the world he would use nuclear weapons while, at the same time, doing everything in his power to prevent war. The communist world was unstable after Stalin’s death, and there were not yet international norms regulating the use of nuclear weapons. These factors led to a series of crises that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war in the 1950s. They included Korea in 1953, Diem Bien Phu in 1954, Taiwan in 1955 and 1958, Suez and Hungary in 1956, and Berlin in 1959. Ike defused each one.

Ike became president determined to achieve nuclear disarmament between the superpowers. This quickly became his main goal. He made his first major proposal, Atoms for Peace, in December 1953. The proposal was for the world’s nuclear weapons to be given to the UN, who would dismantle them. The UN would create an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which would aid nations around the world in achieving peaceful nuclear energy. Most of the world endorsed Atoms for Peace.

The Soviets rejected the proposal. Their government was paralyzed for the first two years after Stalin’s death, and they were not receptive to Ike’s idea. He had hoped to achieve nuclear disarmament in his first year in office. Now, the threat of nuclear war and the goal of nuclear disarmament would dominate his entire presidency.

Ike and his advisors met with a Soviet delegation in Geneva in 1955. He proposed Open Skies, which would allow the US and USSR to fly spy planes over each other’s countries. This would build trust between the superpowers and could lead to nuclear disarmament. Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin was interested in the idea, but Nikita Khrushchev, the real power in the Kremlin, rejected it. Khrushchev said Open Skies was an American ploy to penetrate the Soviet government.

Ike was disappointed by Open Skies’ failure and approved the Killian Report in 1955. The report suggested investments in aerial spying technology. This led to the U2 program, which saw CIA spy planes fly over the Soviet Union and taking aerial photographs, giving the Eisenhower administration information about the Soviet nuclear arsenal. Ike knew the flights violated international law, but he felt they were necessary for national security. He kept them secret from the public until the 1960 U2 Incident. The Soviets, embarrassed that their anti-aircraft weapons could not reach the U2 planes, also kept the program a secret.

The Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957. This meant that they had won the first victory of the Space Race and, more importantly, could soon have an ICBM that could launch across the Atlantic. A panic broke out across the US. The administration organized a panel of scientists and military experts to assess the situation. The result was the Gaither Report, which reported that the US would not survive the decade unless the government built a series of fall-out shelters across the country and that the rest of the economy was put into military spending.

Ike thought this was an enormous overreaction. The Gaither Report recommended turning the US into a garrison state, where the military would control the country. Ike had long sought to avoid this potential outcome of the arms race. Secretary of State Dulles was the only member of the National Security Council to agree with Ike. Ike rejected the report’s advice. Someone leaked the report and Ike was nationally criticized. It was the only time his approval rating went below 50%. Kennedy and other Democrats said Ike was being irresponsible and that they would have done it. Even his Army friends said he was wrong. This cost him political capital and credibility in foreign policy. He refused to increase military spending, and instead, convinced Congress to create NASA and invest in education as the nation’s response to Sputnik.

Khrushchev became the dominant figure in the Kremlin by the mid-1950s following the Suez Crisis and Sputnik. He built on these victories by placing an ultimatum on West Berlin in late 1958, threatening war if the city was not surrendered. Congress and the military wanted to put more troops in the city. Instead, Ike withdrew troops, saying that his only option was to use nuclear weapons. Khrushchev, his bluff called, allowed the ultimatum’s deadline to expire in spring 1959. Ike was so stressed during this crisis he threw his golf club at his personal doctor.

Tension between the superpowers defused after the 1959 Berlin Crisis. Khrushchev came to the US, toured the country, met Marylyn Monroe, and through a tantrum when he was not allowed in Disneyland for security reasons. He met with Ike at Camp David for two days of talks. Ike was skeptical about the meeting and told Khrushchev that the US would defend Berlin and other Western interests. He also said that Khrushchev could be remembered as a great peacemaker if he and Ike reached a deal on nuclear disarmament. The two men announced they would meet again, in Paris, in May 1960 to continue their discussions.

Ike had banned U2 flights in 1958 to calm the Soviets. But he feared the Soviets could have a new weapon system that Khrushchev would use as a bargaining chip in the Paris Summit. Allen Dulles, head of the CIA, convinced him to send a single U2 over the USSR to photograph the Soviet arsenal.

The plane was shot down on May 1, 1960. The CIA told him the pilot was dead. Ike trusted them and said it was a weather plane that had gotten lost over Russia. But Khrushchev had captured the pilot, Garry Powers, alive, and got him to admit that he was a spy. Khrushchev caught Ike in a lie and embarrassed the US.

Ike had failed to stop the arms race. It was the greatest failure of his career. However, this failure does not overshadow his achievement. Ike was president during the most dangerous decade of human history. He was so effective at keeping the peace that it looks boring in retrospect.

Perhaps Ike’s greatest legacy was that his repeated refusal to use nuclear weapons, in spite of crises like Korea, Diem Bien Phu, Taiwan, Suez, and Berlin, raised the threshold on their use. Most Americans, including Ike’s advisors (like Dulles and Nixon), thought it was logical to use the bomb to address these crises, but Ike refused each time. Even the limited use of nuclear weapons in the 1950s could have made them a routine tool in foreign policy. That would have been catastrophic in the long-term. International norms that regulated their use developed by the end of Ike’s presidency. Countries now shun any use of nuclear weaponry; international norms turned them from a tool of first resort to a nonconventional weapon that could never be used by the end of Ike’s presidency. This dramatically reduced the likelihood that nuclear weapons would be used. This means Ike and the New Look are the main reason nuclear weapons haven’t been used since 1945. This was his most important achievement.

It’s true that other parts of his foreign policy are more controversial, such as using the CIA to undermine Soviet-leaning governments in Iran and Guatemala. I think these actions were morally-gray at best and hypocritical given Ike’s belief in the equality of nations. But as ugly as these actions may appear, they are minor compared to both Ike’s achievements in stabilizing the nuclear age and compared to the missteps of other Presidents of that era, from FDR’s agreeing to Stalin’s ethnic cleansing in Eastern Europe and Truman’s NSC 68 to JFK’s reckless escalation of the Cuban Missile Crisis to LBJ’s expansion of the Vietnam War.

If humanity is still around in 2500, I believe two Presidents will stand out from the first couple of centuries of American history: George Washington, for leading the rise of modern democracy, and Dwight Eisenhower, for stabilizing the nuclear age. Ike’s achievement dwarfs any by Lincoln or FDR, and not only is central to the modern age but has few parallels in all of humanity. It is for these reasons that I rank Ike the greatest foreign policy President and hold him in such high regard.

December 7, 2023

Top 10 Foreign Policy Presidents, Number 2: Franklin Roosevelt

Other than Winston Churchill, FDR is likely the single most important person to Allied victory in World War II. That alone earns him one of the top spots on this list.

His primary foreign policy experience was serving as Wilson’s Assistant Secretary of the Navy. As President, his Good Neighbor Policy undid his cousin’s corollary to the Monroe Doctrine and pledged nonintervention in Latin America. He also diplomatically recognized the Soviet Union. Unfortunately, he also refused to partake in a London summit to forge international cooperation in combating the Depression, prioritizing the New Deal instead. This denied him a chance to remove the Smoot-Hawley tariff that triggered a global trade war.

The New Deal dominated the first six years of his presidency, but in 1937 FDR denounced Axis aggression in his Quarantine Speech. The following year he endorsed the Munich Agreement, which he later regretted. He knew American involvement in WWII was inevitable but most Americans opposed intervention and so he slowly (and perhaps overly-cautiously) prepared the country.

The Germans conquered France and the Low countries in summer 1940. The British Expeditionary Force narrowly escaped capture during the Dunkirk evacuation. When the new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, refused Hitler’s peace offerings, he knew that German naval and air forces would soon be attacking Britain. “Never has a nation stood so naked before its foes,” Churchill admitted. At that moment, in all of Britain there were only 600,000 rifles and 500 cannons, many of them borrowed from museums. With Britain on the verge of defeat, US military leaders were unanimous in urging Roosevelt to stop sending our limited supply of weapons overseas and instead focus on rearming at home. But FDR was determined to send whatever he could to Britain, even if it meant putting America’s short-term security in jeopardy.

He traded Britain fifty old Destroyers in exchange for naval bases in the West Indies to help the Royal Navy counter German U-Boats. He won an unprecedented third term in 1940 on the platform of keeping America out of the war, even though he was determined to help Hitler’s enemies in any way he could. Churchill sent Roosevelt a letter explaining that Britain did not have enough money to keep paying for US weapons: “I believe you will agree that it would be wrong in principle and mutually disadvantageous in effect… that after the victory was won with our blood, civilization saved, and the time gained for the United States to be fully armed, we should stand stripped to the bone.”

FDR read the letter over and over again while on vacation. He devised a solution that would become known as the Lend-Lease Act, which said that the US would send weapons and vehicles to any nation at war with the Axis. Only once the war was over would those countries be expected to pay America for the equipment. Lend-Lease was purely Franklin’s idea. With the endorsement of Wendell Willkie (FDR’s Republican opponent in the 1940 election) the bill passed Congress.

FDR explained his idea to the press: “Suppose my neighbor's home catches fire, and I have a length of garden hose four or five hundred feet away. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him to put out his fire...I don't say to him before that operation, ‘Neighbor, my garden hose cost me $15; you have to pay me $15 for it.’... I don't want $15--I want my garden hose back after the fire is over.” In his next Fireside Chat, Roosevelt said that the US must become the “arsenal of democracy” to thwart the Nazis’ dream of world conquest.

When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, FDR again overruled his military advisors and sent Lend-Lease aid to the Red Army. 70% of the bullets, weapons, and vehicles the Soviets used in World War II came from the United States. America sent Russia 15,000 aircraft, 7,000 tanks, 350,000 tons of explosives, 2,000 locomotives, 11,000 railcars, three million tons of gasoline, 540,000 tons of rail, 51,000 jeeps, 375,000 trucks and 15 million pairs of boots. At the Tehran Conference in 1943, Stalin declared, “The most important thing in this war are the machines. The United States is a country of machines. Without the use of those machines, through Lend-Lease, we would lose this war.”

FDR also mediated Allied strategy, first siding with Churchill by invading North Africa and the Mediterranean so America could increase its might, and then siding with Marshall, Eisenhower, and Stalin by directing the invasion of Western Europe. Only FDR appears able to see how both strategies were necessary for victory. It is perhaps his greatest contribution and raises the question of his indispensability to winning the war.

He was haunted by Woodrow Wilson’s failure to secure America’s admission into the League of Nations and dreamed of a new international organization that could secure the peace won by the Allied victory in World War II and preserve the Grand Alliance into the post-war world. The first step was the Atlantic Charter. In August 1941, Roosevelt met with Winston Churchill off the coast of Newfoundland. FDR pledged more Lend-Lease aid to Britain, promised that the US navy would help shield convoys from Nazi attack off the coast of Iceland, but refused to commit any American forces to defeating Hitler. The document they issued called for “the final destruction of Nazi tyranny,” but it also promised a postwar world in which every nation controlled its own destiny, an end to the kind of colonialism Churchill had stood for all his life. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt and Churchill proclaimed that the nations at war with the Axis were the United Nations (the suggestion came from Harry Hopkins). Roosevelt devised the organization as we currently know it (with a General Assembly and a Security Council). In order to secure Stalin’s pledge of Soviet entry into the UN, Roosevelt made significant concessions to the communist dictator. The organization was not officially established until after FDR’s death.

If he defeated fascism and established a global taboo against conquest, overturning thousands of years of human history, how is he not Number One? First, because my top pick (yes, you know who he is) is just that formidable, but also because FDR made some missteps that should be better understood.

I’ve written about these in a prior post, but am placing them here again because of their relevance:

Most WWII buffs know that the US placed an oil embargo on Japan after Japan absorbed Indochina from Vichy France in autumn 1941 and that this was Japan’s prime motive for attacking Pearl Harbor. But how many know that the State Department made the move without FDR’s direction? FDR met Churchill in August off the coast of Newfoundland to introduce the Atlantic Charter and in his absence Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson severed Japan’s ability to purchase US oil. FDR was stunned and knew the move was provocative but 51% of Americans approved of it and so he left in place.

Emperor Hirohito gave Prime Minister Konoye one month to reach a deal with Washington. Konoye secretly met with the American ambassador and proposed he meet with FDR in Hawaii to establish the framework for a deal. This was sent to the State Department, which convinced FDR that meeting Konoye without a deal in place beforehand would be seen as another Munich Agreement. FDR agreed and sent conditions Konoye had to fulfill before the meeting, which included Japan’s withdrawal from the Tripartite Pact and from its war in China. Konoye had no way of fulfilling these terms and resigned as Prime Minister. He was replaced by Hideki Tojo.

Acknowledging this diplomatic blunder is not engaging in the conspiracy theory that FDR was responsible for December 7, but it is a large piece of his foreign policy record that is almost never mentioned even by professional historians (I learned of it in Jean Edward Smith’s FDR biography). It’s probably one of the largest foreign policy blunders in presidential history, even if, in the long run, the world is better off without the Japanese Empire. Let’s discuss two more.

The Lend Lease Act was arguably FDR’s greatest contribution to Allied victory. Some have even cited it as proof that he “saved the world.” This argument has merit, for it transformed the US into the Arsenal of Democracy and helped fund the British, Soviet, and Chinese war efforts. But FDR also used it to influence his postwar priorities. His seemingly innate trust in the USSR, which he saw as a progressive state, and suspicion of Britain (given his dislike for colonialism), was perhaps his worst miscalculation. He gave Britain the bare minimum it needed to fight the war, aiming to bankrupt London so it couldn’t hold onto its empire. Simultaneously, he gave Stalin a blank check, strengthening the Soviet position in the early Cold War. We can see the legacy of this decision today, not only in the Russo-Ukraine War, but in the rushed partitions of Israel-Palestine and India-Pakistan that resulted in entrenched conflict lasting over 75 years. I write this about a month after Hamas’ attack on October 7.

The following documentary details FDR’s strategy for bankrupting Britain:

https://youtu.be/aoqV-EuYEOQ?si=pTcVe...

The final episode I want to highlight occurred in the November 1943 Tehran Conference. Churchill wanted to detach Prussia from Germany by moving it into Poland and proposed moving Poland’s border to the Oder and Neisse rivers. Put more simply, he said the Allies should move Poland westward at Germany’s expense and to the USSR’s gain. Stalin agreed and so did FDR, who only asked that the move not happen until after the 1944 election so he did not lose the Polish vote. This agreement led to Stalin forcefully moving 10 million Germans and millions of Poles between 1945 and 1950, an ethnic cleansing that killed at least half-a-million people. He did it with FDR’s blessing.

I think these failures should deny FDR the top spot, but I still rank him as the second best foreign policy President in American history. There’s only one other who also saved the world, and who did it confront the greatest and most complex stakes imaginable.

Say it with me…

December 1, 2023

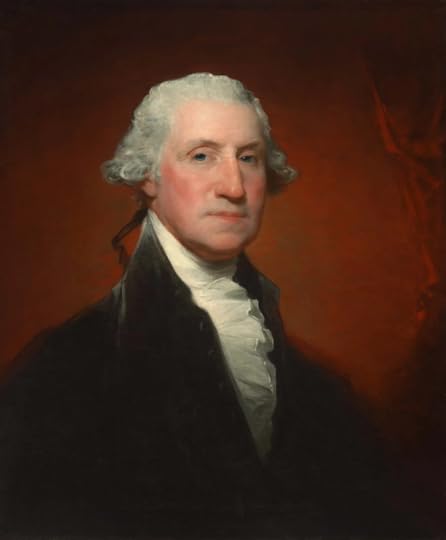

Top 10 Foreign Policy Presidents, Number 3: George Washington

In the 1790s, the United States faced challenges in foreign relations unsurpassed in gravity until World War II. Britain and Spain still blocked access to the Great Lakes and Mississippi River, thwarting America’s westward expansion. The French Revolution, which began in 1789, ignited a war in Europe in 1792. The revolutionary ideology turned this European power struggle into a total war where entire populations were mobilized for conflict. President Washington assembled his cabinet to figure out a response to the crisis. The risk of getting pulled into Europe’s war and potentially fighting a superpower like Britain or France meant that the young republic’s survival was at stake.

Secretary of State Jefferson advocated upholding the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France. Secretary of Treasury Hamilton wanted Neutrality that expressed favoritism toward Britain. Washington took ideas from each and declared the Neutrality Proclamation, which prohibited either the American government or private citizens from acting on behalf of either Britain or France. This caused outrage by both those Americans who supported France and those who thought Washington was overstepping his Constitutional bounds. Washington had made his decision without consulting Congress, establishing an important precedent for Executive Branch initiative in foreign policy.

Washington was a foreign policy realist, which means that he thought that nations should pursue their interests when conducting geopolitics, not morality or ideology. Alliances formed when the interest of multiple nations coincided, but countries did not have friends. This puts Washington in the same camp as geopolitical giants like Otto von Bismarck, Richard Nixon, and Henry Kissinger. Although he appreciated France’s help in the War of Independence, Washington no longer saw the alliance with France as beneficial to the United States and did not feel obligated to come to France’s aid.

The biggest foreign policy crisis of Washington’s presidency dominated his second term. The British refused to honor the obligation they made in the Treaty of Paris (which ended the War of Independence) to vacate forts around the Great Lakes, where they stirred up trouble with Native American tribes and restricted American migration into the Ohio Valley. Additionally, the British navy seized American ships carrying French goods in an attempt to undermine France’s war effort. To avoid war, President Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London to negotiate a settlement. Jay’s treaty provided for British evacuation of the northwest posts and gave America a ‘most favored nation’ status in Britain’s trade, and vice-versa. This swelled American exports. It was a commercial treaty that enormously benefited both signatories while hurting neither. Congress narrowly passed the treaty, and a backlash was initiated in the press by Jefferson’s allies, who now saw Washington as Britain and Hamilton’s pawn. Jay’s image was burned in effigy. Madison, a leading figure in the House, tried to withhold funds for the treaty but was defeated.

More ominously, the French saw the Jay Treaty as America taking Britain’s side in the war. France began pursuing American ships, resulting in a crisis that dominated John Adams’ presidency. Washington was exhausted by the aftermath of the Jay Treaty and was upset that his legacy was being damaged by bitter partisanship. He decided not to run for a third term, setting another precedent. Washington had exploited the great power rivalry to America’s advantage and avoided a costly war with Britain. Before he left office, Washington negotiated the Treaty of Madrid with Spain, which was similar to the Jay Treaty. Spain recognized the US’s boundary claim east of the Mississippi, removing the last obstacle to America’s westward expansion. This crowned Washington’s life work.

Washington not only navigated the crises of his time. His Farewell Address articulated a policy framework which was a roadmap for America to become a great power by 1900. A powerful Union. Industrialization. Western expansion. Avoid unnecessary wars. The country more or less followed this checklist (with some obvious large exceptions), resulting in the US becoming the global superpower in the 20th century. Such a legacy secures Washington’s place among the top three. Why isn’t he higher? Because the top two foreign policy Presidents can both claim something that Washington cannot: they saved the world.

November 21, 2023

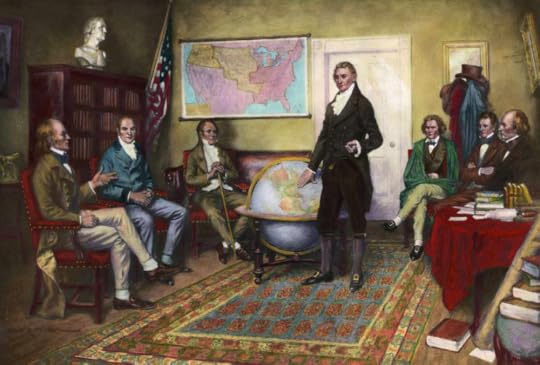

Top 10 Foreign Policy Presidents, Number 4: James Monroe

I had always respected Monroe and considered him a top 10 President, but my appreciation for his presidency rose exponentially while researching and writing The Middle Generation. Like with Eisenhower, I learned that because Monroe presided over peace and prosperity (nicknamed the Era of Good Feelings) people assume that he faced less challenges than most Presidents and his reign was uneventful. That was not the case.

Monroe’s era was in the aftermath of Napoleon’s defeat. Spanish America was fighting for its independence from her colonial master. Most Americans supported their southern brethren, including Speaker of the House Henry Clay, but Secretary of State John Quincy Adams (the co-owner of this ranking placement) convinced Monroe that recognizing the rebels risked war with Spain and the Holy Alliance.

Instead, they took advantage of the Spanish Empire’s collapse to establish the US as the dominant power in North America. Adams spent 1818 and early 1819 negotiating with Luis de Onís y González-Vara, Spain’s minister, pushing Spain to cede Florida and Spain’s claims to the Pacific Northwest. Negotiations stalemated until General Jackson captured Florida. The story behind the Onis-Adams Treaty and Jackson’s invasion is fascinating, but I portrayed it in all of its complexity in The Middle Generation and feel that I can’t do it justice here. The important point is that Monroe and Adams succeeded and the US touched the Pacific Ocean for the first time.

Monroe’s second term contained a major crisis that’s been forgotten by history. The Holy Alliance, formed of Prussia, Austria, and Russia, sought to enforce peace and stability in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars and they saw South American independence as likely to provoke a catastrophe similar to the French Revolution, which had followed American independence. The Alliance refused to recognize the South American republics and said they would invade and reimpose Spanish rule. This was likely a bluff intended to scare the US into making a joint statement with Britain opposing the Alliance’s intentions. Adams feared this would tell the world that the US could not defend the Western Hemisphere on its own, crippling its rise. The result was a diplomatic and political chess match which culminated in the climax of Monroe’s presidency and a certain statement that bears his name.

I rank Monroe as the 4th best foreign policy President because I think he and Adams elevated us from a minor power to a medium power in the world and contributed to the Western Hemisphere gaining independence from European colonialism. That is an underrated achievement that deserves its place in history.

November 16, 2023

Interview with Brian Feinblum about "The Middle Generation"

1. What inspired you to write this book?

I have wanted to write biographical fiction since watching Lincoln in theaters in 2012. I wrote The Eisenhower Chronicles while in law school. That book was structured like an HBO miniseries, allowing me to experiment and grow as a writer with each episode. Upon completing it, I wanted my next book to be of a similar topic so I could push what I’d learned even further. I chose John Quincy Adams because, like Eisenhower, he had a brilliant mind for foreign policy but was also a bridge between the Founders and Lincoln. I started researching him and, once I realized that the Monroe Doctrine, which he wrote as Secretary of State, was the winning chess move in his showdown with Europe over South American independence, I knew I had my story. I was all the more excited because Europe at the time was controlled by the Holy Alliance, a group of monarchies who kept the peace in the continent through force after Napoleon’s defeat. Their leader was an Austrian diplomat named Metternich, who was arguably the greatest diplomat in European history. That meant the story could be framed as a clash between Adams and Metternich, which interested me and, I hope, interests readers.

2. What exactly is it about and who is it written for?

It’s about Adams’ time as Secretary of State, from 1817 until 1825. This places it in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. Spain’s colonies in South America are fighting for their independence, and Adams hopes the US can take advantage of this by absorbing Florida and Spain’s holdings in the Pacific Northwest. Doing so would help secure control of North America and, he hopes, his victory in the 1824 presidential election. What unfolds is a multifaceted political thriller of Adams navigating a series of challenges and crises. First is his aforementioned struggle with Spain. Second is the Missouri Crisis, which threatened the Union and is when the North learns that the South won’t give up slavery willingly. Third is his climactic showdown with Metternich, which forms the core of the novel and culminates in the Monroe Doctrine. Last is the election of 1824, which pits Adams primarily against Andrew Jackson and which is famously one of the most chaotic elections in American history (some readers may be familiar with the notorious corrupt bargain). Another subplot portrays the pressure of being John and Abigail Adams’ eldest son, which distorts Adams’ personality, and for which he emotionally abuses his own family.

This novel is for fans of American history, especially those eager to learn about a largely forgotten crisis/era. I also think fans of political dramas with partnerships forming and breaking and with a lot of strategic calculations will have a lot of fun with this read.

3. What do you hope readers will get out of reading your book?

I hope they feel like they’ve stepped back into the early 19th century with all of its attitudes, sights, and smells. More importantly, that they’ve spent some time with John Quincy Adams, feel like they know him, his voice, his family, and his beliefs. He’s a far more fascinating man than I expected when I started researching him, and I hope I conveyed that.

I also hope that people who’ve struggled with overwhelming pressure to be successful will relate to him and know that even Presidents have shared such experiences. Finally, I hope that they learn a bit about the second generation of Americans and their conflict with the Holy Alliance that produced the most famous foreign policy document in US history.

4. How did you decide on your book’s title and cover design?

My original idea for the title was The Ballad of John Quincy Adams, mostly because I like musical ballads and I thought the name was pretty. But no one else liked that title because the novel is a fast-paced political thriller and so calling it a ballad didn’t make any sense. I liked The Middle Generation because it highlighted how the book focuses on the second of the three generations in America’s classical era that stretched from the Revolution until the Civil War. That generation is overshadowed by those two bookends, and so telling their story through Adams provided insight into an overlooked part of US history. I included A Novel of John Quincy Adams and the Monroe Doctrine to make clear both the book’s main subject and the fact that it’s a historical fiction novel and not nonfiction.

I primarily asked the publisher to include a chessboard on the cover to help convey that it’s a political thriller and not slow-moving or dull. Everything else I left to her discretion.

5. What advice or words of wisdom do you have for fellow writers – other than run!?

A writer needs the patience to build the experience necessary to produce quality work, both in their career and for individual projects. Remember what Hemingway said about first drafts. Part of learning what you’re doing is listening to feedback and studying the masters while still trusting your own judgment. Most writers who can persist this way will develop their unique voice and make their own contributions to the literary world. Similarly, I would say a writer must learn to focus on what they’re doing and ignore the outside world when it attempts to demoralize or distract them. Treat most such efforts as static noise.

6. What trends in the book world do you see -- and where do you think the book publishing industry is heading?

I think the single biggest trend of the past several years has been the atomization of the literary world. There are so many options and subgenres for readers to pick from that they can choose whatever they’d like regardless of cultural trends. This gives writers more room for carving out their individual niches and thereby earn an income from their work but also dilutes the readership and reduces the likelihood of future books entering the canon as classics. Has any American writer achieved such status since Toni Morrison and Cormac McCarthy?

7. Were there experiences in your personal life or career that came in handy when writing this book?

I’d gone to law school at my parents’ urging and found it to be a bad fit. That helped me relate to Adams as his parents demanded he become President, though of course his situation was far more stressful. But I appreciated how he felt obligated to please them while struggling to do so and I think other people who have experienced parental pressure will also relate to his journey.

I was also able to draw on my years of historical study. My college thesis was on how Charles de Gaulle inspired Nixon’s opening to China, leading me to read a lot of diplomatic history. I learned about Metternich and his role in defeating Napoleon and in shaping the Concert of Europe at that time. This allowed me to appreciate the threat he’d pose if I set him as the antagonist.

I also think that The Eisenhower Chronicles provided critical experience in writing biographical fiction. I tried something a little different with every chapter of that book. Two chapters were in the first person, a style I enjoyed more than I expected. That convinced me to write The Middle Generation in the first person, which fit the story well.

8. How would you describe your writing style? Which writers or books is your writing similar to?

Portraying the protagonist’s mind and personality as realistically and interestingly as possible is my top priority with each novel. I find the different layers of people’s psyches and how their conscious and subconscious desires collide to be endlessly fascinating. Conveying character arcs in this way is my main goal as a writer (think of how Walter White’s pride overrides his adherence to civic and familial norms in Breaking Bad, as an example).

Dialogue is my favorite type of writing and my books are full of it. I do my best to give each character a distinct voice so their conversations and debates are as interesting as possible and develop an almost musical rhythm.

I look to Ernest Hemingway as my role model for prose. I love how his writing is simultaneously accessible and sophisticated, especially the rhythm he builds by connecting various clauses with the word “and.” I also like Elmore Leonard both for his dialogue and his prioritizing his prose’s readability, even deploying fragments to make it smoother.

As The Middle Generation is a biographical novel, I would compare it to I Claudius, Wolf Hall, and Hamnet, but in the style I expressed here.

9. What challenges did you overcome in the writing of this book?

I wish I knew more about Adams before I told people I was writing about him! I had primarily focused on the twentieth century and so this novel required a huge amount of research. Most intimidating was his 51-volume diary. I would still be researching if the Massachusetts Historical Society hadn’t added a search engine that allowed me to target specific keywords and topics. I accumulated over 400 pages of notes that I looked at when writing every paragraph.

10. If people can buy or read one book this week or month, why should it be yours?

I believe that the best works of art are both entertaining and meaningful. An entertaining premise and story hooks the audience and moves them along and they exit remembering how its depth made them think or feel in ways they hadn’t previously. I wanted The Middle Generation to embody both of these qualities. It is a political thriller and moves at a fast pace. An important plot beat or twist occurs in almost every scene. The dialogue, though informative, is exciting, often explosive, and is the action driving the novel forward. But at the novel’s heart is a fascinating historical figure who I did my best to resurrect in all his hopes, ambitions, and contradictions. My hope is that readers not only learn about Adams and his era but, just maybe, themselves too by absorbing his struggle and journey. November 2023, the release month for this book, also marks the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine, making it an excellent time to delve into the mind of John Quincy Adams.