Adam Thierer's Blog, page 79

December 2, 2012

The Troubling Growth of High-Tech Regulation, Lobbying, and Rent-Seeking

I caught this tidbit today in a Washington Post article about Julius Genachowski’s tenure as Federal Communications Commission chairman:

He wound up presiding over a crucial period in which the powerful companies of Silicon Valley turned into Washington power players. Lobbying the FCC has become a major economic franchise. Each day, hundreds of dark-suited lawyers crowd the antiseptic, midcentury-modern agency building.

Can anyone think this is a good thing? To be clear, I don’t think Genachowski is solely responsible for Silicon Valley innovators getting more aggressive in Washington or for tech lobbying becoming “a major economic franchise” at the FCC. There’s plenty of blame to go around in that regard. Regardless, every legislative and regulatory action that opens the door to greater regulation of the information economy also opens the door a bit wider to unproductive rent-seeking and cronyist activities. Moreover, every minute and every dollar spent focusing on making legislators and regulators happy is another minute and dollar that could have better been spent making consumers happy in the marketplace. It’s a pure deadweight loss to society.

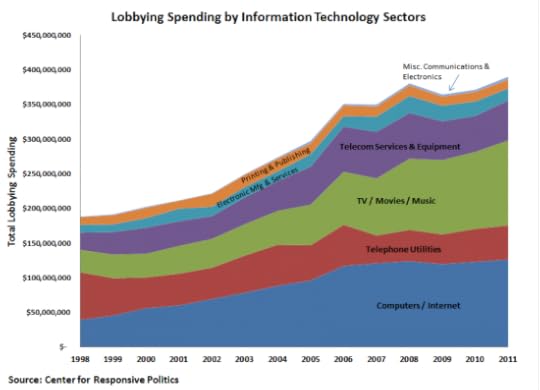

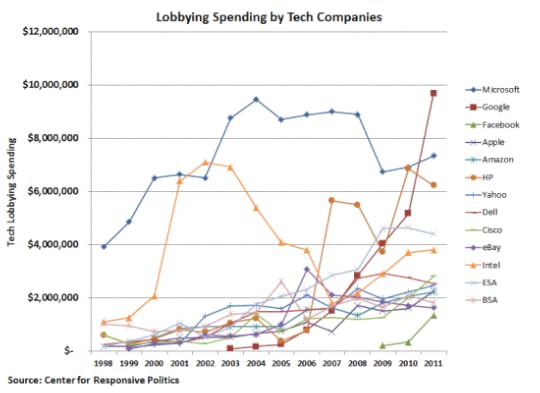

And there has been a remarkable expansion in such tech lobbying activity over the past decade, as the following charts illustrate. The first shows the dramatic growth of lobbying by computer and Internet companies relative to other sectors and the second shows lobbying spending by specific computer and Internet companies. [Click to enlarge.]

Sadly, this situation isn’t going to improve any time soon. As I noted in a 2010 Cato essay (“The Sad State of Tech Politics“) and other essays here (see them below), lobbying by information technology companies is absolutely exploding. Google and Facebook set quarterly records of their own recently, but it’s not just the big dogs like them. Everyone is beefing up. As the politics of the parasitic Belwway economy increasingly replace the cut-throat rivalry of the market economy, consumers and innovation will suffer.

These firms aren’t coming to Washington because they are just dying to be here. They first come here out of necessity: they are looking to cover their asses. The more Washington seeks to regulate, the more these firms come to believe that they have to be here to make themselves heard. And I can’t blame them. But very quickly they come to realize that all this regulatory activity can present opportunities as well as threats. Regulation is often used as a club to beat back new innovations and rivals. Here’s the sad history of that. Worse yet, lobbying activity eventually takes on a life of its own. As political scientist Lee Drutman points out in his dissertation on the business of lobbying, “lobbying creates its own demand… (and) has a self-reinforcing dynamic. Once companies come to Washington, they stick around, and usually expand. And with each passing year, more companies come to Washington”:

once they hire lobbyists and set up lobbying offices and become active in trade associations, they start to see the benefits of political participation. Lobbyists are there to point out new potential opportunities and new threats, and to make the case that being engaged politically is good for the bottom line. Companies get involved in more issues and more ongoing battles. And once they’ve paid the start-up costs of learning about Washington and building relationships, the cost-benefit equation of being politically engaged shifts even more in favor of staying and doing more.

In other words, there’s a sort of “Say’s Law” of lobbying at work: supply creates its own demand. That certainly seems to be true for the high-technology companies and sectors mentioned above. They are falling over themselves in a mad rush to see who can beef-up their lobbying operations faster. They are doing this even though there isn’t always a compelling case for them to be doing so. But it doesn’t make a difference. Lobbying has taken on a life of its own. It is rationalized by tech leaders telling themselves that ‘we either do this or we get screwed,’ all the while being egged on to do so by a professional class of inside-the-Betlway lobbyists, consultants, PR people, trade associations, and reporters who all insist that it’s just the way business is done nowadays — and who all make their money by encouraging the grow of the parasite economy.

Pathetic.

Additional (Miserable) Reading:

“On Facebook “Normalizing Relations” with Washington” (March 29, 2011)

“Kinsley on Cyber-Politics & ‘How Microsoft Learned the ABCs of D.C.‘” (Apr. 5, 2011)

“The Internet, Politics, Lobbying & the ‘Big Spend‘” (Jan. 24, 2012)

“FCC Commish Robert McDowell on Regulatory Failure & “Regulate My Rival” Politics” (June 28, 2012)

“DC’s LivingSocial Cronyism Experiment Already Going off the Rails” (Nov. 29, 2012)

November 30, 2012

On copyright, conservatives and libertarians should focus on what unites us

Yesterday I heaped praise on James V. DeLong for articulating a reasoned conservative defense of copyright that also highlighted just how much common ground he shares with those conservatives and libertarians that are concerned with the current copyright system’s infirmities. I also said that I disagreed with some of the arguments he made in his essay and that I might address those in a later post. That’s no longer necessary because Jordan Bloom of the American Conservative has put his finger on just about everything I would have taken issue with in DeLong’s column.

Bloom has been doing yeoman’s work covering the retracted RSC memo story. I believe that he was the first person to write about the memo before it was retracted. For that I thank him. But, I have to disagree with some of his response to DeLong. While he (correctly in my view) takes DeLong to task for conflating copyright with traditional property rights, he treats this intellectual position as make-or-break for copyright reform. This is wrong.

Bloom writes, “Republicans will get nowhere on this issue without drawing a clear distinction between both types of property.” And he concludes:

We won’t be able to proceed to a serious discussion about what balance of IP protection we ought to have until we stop pretending intellectual property is the same as other types of property and that it’s a God-given right to have the government enforce its exclusivity, in the case of copyright, 70 years after the creator’s death.

I take his point, that there is a confusion about the nature of copyright as property and that it often makes discussion about reform difficult. Many conservatives employ the logic of “property is good, copyright is property, therefore more and stronger copyright is great.” We need to point out why that logic is flawed, as Bloom does in his response. But, we should not excoriate folks like DeLong when they ultimately agree with us.

As I said yesterday, in his article DeLong agrees with the likes of me and Bloom that we should reform copyright to have shorter copyright terms and formalities like registration and renewal. That common ground is what we should be focusing on, not the first principles distinctions that divide us. Even Ayn Rand, a property rights absolutist if there ever was one, agreed that there must be limits on copyright.

Whatever paths DeLong, Bloom and I took to get to our positions, it shouldn’t matter for the practical project of reforming copyright. Some of us are natural rights types and others utilitarians, some of us are Objectivists and others paleoconservatives. If we can all agree, whatever our first principles, that the current copyright system is an out-of-control federal program that is beset with terrible public choice problems, then I think we should put aside our philosophical disagreements about the ideal of copyright and get to work on fixing the broken system we have now.

There is more common ground among conservatives, libertarians and Republicans on the need for paring back copyright than our squabbling lets on. Instead of arguing about the extremes, I think we should work hard to reach consensus and then provide leadership.

November 29, 2012

Three cheers for James DeLong on copyright!

Over the past couple of weeks I have been pointing out examples of conservative/libertarian thinking and rhetoric on copyright that is unhelpful and which I think we should abandon as a movement. This kind of rhetoric is usually reactionary, ad hominem, and uninformed. So, I’m very happy today to point you to an example of some excellent thinking and rhetoric from a free-market/property-rights perspective.

In National Review today, James V. DeLong has an article addressing the retracted RSC memo that sparked the recent debate over copyright among libertarians and conservatives. Now, DeLong makes some arguments with which I disagree, including about the nature of copyright as property not unlike personal property and about the just desert of authors, and I may address those arguments in a later post. But, I think it’s more worthwhile to point out where DeLong and I agree because it shows that in fact those of us who are for liberty, limited government and economic efficiency actually don’t disagree on copyright as much as our arguments on specific proposals might lead one to believe. While dinging the RSC memo as “mediocre,” DeLong nevertheless agrees:

Some of the specific problems noted in the paper and elsewhere are very real: Copyright terms are too long; rights are overly convoluted and hard to pin down; transaction costs are too high; the easy availability of copying is attriting the creative community; orphan works, for which the copyright holders are unknown, present problems. The list is long.

We probably need a clean-sheet rewrite of copyright law, but the solutions to many current problems are far from obvious, and the risks of any such enterprise are so great as to daunt everyone with a stake in the system. So we keep muddling along, with the confusion abetted by those who profit from the current mismatch between law and technology.

Confusion is also caused by the content industry. Much of it really is as greedy and rapacious as its critics contend. The only property rights it cares about are its own; it has no sympathy for anyone caught up in the toils of the EPA or the local zoning board (unless the issue involves Malibu beach property, of course).

Three cheers! I am so happy to discover so much common ground. DeLong goes on to make some concrete proposals, including this:

Many specific reforms should be enacted. My list would include shorter copyright terms; a requirement of registration and renewal, to show seriousness; a one-time requirement of registration of existing works to get rid of the orphan-works problem; and centralized databases to reduce transaction costs.

Huzzah! This is very similar to my list as well! Unfortunately, DeLong concludes that “Despite all these concerns, the temptation for Republicans to reflexively embrace the foes of copyright should be resisted, because the church of property rights is greater than its servants.” But why should Republicans accept an admittedly bad status quo when it presents a perfect opportunity for the GOP to demonstrate leadership? It need not have to “reflexively embrace” copyright reformers on the left who don’t have the same respect that we libertarians and conservatives have for property rights. It can instead provide an alternative that reforms the mess that is copyright today and also respects property rights and the Framer’s original intent when they included copyright in the Constitution.

Here’s what I say: The GOP should take the list that DeLong provides and turn it in to a bill. Such a reform would not only be compatible with strong property rights, but it would also be the true small government position.

P.S. The new book I’ve edited on copyright from a free market perspective will be available in the next few days, so stay tuned.

Issa’s Plan to Hold Back the Flood of Internet Regulation

With each passing year, Washington’s appetite for Internet regulation grows. While “Hands Off the Net!” was a popular rallying cry just a decade ago—and was even a shared sentiment among many policymakers—today’s zeitgeist seems to instead be “Hands All Over the Net.” Countless interests and regulatory advocates have pet Internet policy issues they want Washington to address, including copyright, privacy, cybersecurity, online taxation, broadband regulation, among many others.

Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA) wants to do something to slow down this legislative locomotive. He has proposed the “Internet American Moratorium Act (IAMA), which would impose a two-year moratorium on “any new laws, rules or regulations governing the Internet.” The prohibition would apply to both Congress and the Executive Branch but makes an exception to any rules dealing with national security.

Will Rep. Issa’s proposal make any difference if implemented? Any congressionally imposed legislative moratorium is a symbolic gesture and not a binding constraint since Congress is always free to pass another law later to get around an earlier prohibition. So, in that sense, a moratorium might not change much. Nonetheless, such symbolic gestures are often important and Issa is to be commended for at least trying to raise awareness about the dangers of creeping regulation of online life and the digital economy.

If policymakers really want to take a more substantive step to slow the flow of red tape, they should consider a different approach. Instead of (or, perhaps, in addition to) a two-year legislative moratorium, they should impose a variant of “Moore’s Law” for information technology laws and regulations. “Moore’s Law,” as most of you know, is the principle named after Intel co-founder Gordon E. Moore who first observed that, generally speaking, the processing power of computers doubles roughly every 18 months while prices remain fairly constant.

As I argued in a Forbes column earlier this year, we should apply this same principle to high-tech policy. With information markets evolving at the speed of Moore’s Law, we should demand that public policy do so as well. We can accomplish that by applying Moore’s Law to all current and future laws and regulations through two simple principles:

Principle #1 – Every new technology proposal should include a provision sunsetting the law or regulation 18 months to two years after enactment. Policymakers can always reenact the rule if they believe it is still sensible.

Principle #2 – Reopen all existing technology laws and regulations and reassess their worth. If no compelling reason for their continued existence can be identified and substantiated, those laws or rules should be repealed within 18 months to two years. If a rationale for continuing existing laws and regs can be identified, the rule can be re-implemented and Principle #1 applied to it.

This would be a more effective way to get Internet over-regulation under control than any temporary moratorium. Again, if critics protest that some laws and regulation are “essential” and can make the case for new or continued action, nothing is stopping Congress from legislating to continue those efforts. But when they do, they should always include a 2-year sunset provision to ensure that those rules and regulations are given a frequent fresh look.

We often hear the legitimate complaint that ‘law can’t keep up with the Internet.’ It’s time we do something to act on that sound instinct. As I noted in concluding that earlier Forbes essay, only by demanding that regulations be sunset on a regular timetable can we keep government power in check and ensure unnecessary and outdated regulations don’t derail America’s high-tech economy.

DC’s Social Media Surveillance: Privacy vs. Customer Service Considerations

As I noted in an addendum to my previous post, less than an hour after I posted an essay about how the District of Columbia’s subsidy deal with LivingSocial was potentially set to unravel, I received a call from two representatives of the D.C. Mayor’s office asking me to clarify a few aspects of the deal. The tone and substance of the call was courteous and profession from the start and I told them I would be happy to post a quick update to my essay letting readers know of the points that they wanted stressed.

After I did so, however, I kept thinking how strange it was that I received such a quick response from the Mayor’s office about my little post. After all, I can’t imagine that the Technology Liberation Front is on the top of their morning reading list! I just figured that someone in the Mayor’s office probably had a Google Alert set up that caught it. But then, as luck would have it, I was reading through the Wall Street Journal at lunch and came across a story entitled, “In D.C., Social-Media Surveillance Pays Off” by Sarah Portlock. She reports that:

The local government in the nation’s capital is paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to a startup to gather comments on Twitter, Facebook and other online message boards as well as the government’s own website. The data help form a letter grade for the bureaucracies that handle drivers licenses, building permits and the like. These social-media analytics services are already common for businesses such as restaurants and hotel chains that want to go beyond the comment cards most customers ignore. The D.C. experiment suggests governments are beginning to mirror the private sector in seeking real-time unvarnished feedback.

The D.C. government apparently has a 2-year $670,000 contract with newBrandAnalytics, Inc. to gather social media feedback and insights about the District. So, I figure that’s how the folks in the D.C. Mayor’s office stumbled upon my little rant. I had posted a link to my essay on both Twitter and Google+ and they probably got an immediate report back about it.

In any event, that got me wondering about how people are going to respond to this sort of “surveillance” of social media sites and activities by governments.

I can imagine that some people will feel it’s “creepy” and suggest it violates some privacy norms. But the sort of “surveillance” happening here isn’t the typical “law-and-order” stuff. What we’re talking here about is really just the same sort of customer service efforts that many private sector companies undertake regularly. Like those private companies, the District is interested in getting feedback about how it’s doing its job. The Journal article quotes Nicholas Majett, head of the District’s Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs, saying: “Knowing that every day you’re going to get a report about how you’re doing, that actually puts you on your toes and makes sure you’re doing the best possible job.”

In that sense, I applaud the District’s effort to gather impressions and insights from social media sites and use them to improve their public service record. (Of course, I’m of the mind that the District government is doing far more than it needs to and that many of its licensing and regulatory processes, for example, should be completely abolished or privatized. I’m also not sure that the system is worth $670,000 of taxpayer money.)

About the only way I could imagine any of this raising privacy concerns is if the District was gathering these social media insights, matching them up with other databases they have access to, and then using that information to somehow intimidate citizens or deny them some sort of service. It’s always easy to conjure up privacy boogeyman stories like that, but until there is any evidence that social media insights are being used in some nefarious way, I’m not too worried about what the District is doing here.

Going forward, however, it will certainly be interesting to see what happens when government “customer service” efforts such as these grow more sophisticated and come into conflict with certain privacy expectations. While I’m not of the mind that you really have much of a reasonable expectation of privacy on Facebook, Google+ or Twitter, I can imagine that many people are going to be freaked out if they start getting regular emails, tweets, texts, or even phone calls from government officials responding to complaints that were written just moments prior on their favorite social media sites.

Of course, these efforts are also worth monitoring to see if they actually do anything to help improve government service / responsiveness. If these efforts can make my DMV experience even moderately more tolerable, I would probably consider them a success!

DC’s LivingSocial Cronyism Experiment Already Going off the Rails

In July 2012, the D.C. Council approved the Social E-Commerce Job Creation Tax Incentive Act of 2012. The deal provided LivingSocial, a popular online coupon service, with corporate and property tax exemptions in Washington, D.C. worth approximately $32.5 million over five years beginning in 2015. Legislators feared that LivingSocial would relocate to areas with a lower tax rate. In exchange for the $32.5 million, LivingSocial said it would attempt to add 1,000 employees to its payroll (roughly doubling its number of employees in the District), although no contractual guarantee for job creation exists and even though the firm had never been profitable. Some of the few contractual obligations required for LivingSocial to receive these tax exemptions are that it must establish a program to mentor D.C. high school students, provide internships for D.C. students, and stay located in the District. LivingSocial must also ensure 50% of newly hired employees live in the District in order to receive the Act’s full $32.5 million in exemptions.

In July 2012, the D.C. Council approved the Social E-Commerce Job Creation Tax Incentive Act of 2012. The deal provided LivingSocial, a popular online coupon service, with corporate and property tax exemptions in Washington, D.C. worth approximately $32.5 million over five years beginning in 2015. Legislators feared that LivingSocial would relocate to areas with a lower tax rate. In exchange for the $32.5 million, LivingSocial said it would attempt to add 1,000 employees to its payroll (roughly doubling its number of employees in the District), although no contractual guarantee for job creation exists and even though the firm had never been profitable. Some of the few contractual obligations required for LivingSocial to receive these tax exemptions are that it must establish a program to mentor D.C. high school students, provide internships for D.C. students, and stay located in the District. LivingSocial must also ensure 50% of newly hired employees live in the District in order to receive the Act’s full $32.5 million in exemptions.

Just a few months after the deal was struck it had already become apparent just how risky of a bet the DC government has made with taxpayer dollars. In late November 2012, LivingSocial announced a net loss of $566 million for the third quarter and that hundreds of employees would be laid off. The promise to roughly doubling the size of its DC-based workforce seems fairly unlikely and some analysts doubt the company will survive much longer.

This serves as another case study for just how foolish it is for governments to make risky, taxpayer-backed bets on information tech companies. Sadly, it’s not the only case study in this regard. In a forthcoming white paper, Brent Skorup and I will be documenting the troubling rise of high-tech cronyism across America. Motorola, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Groupon, film studios, video game makers, and many other information technology companies are lining up with hat in hand and asking for handouts or special favors from state and local governments. Tax credits and other tax code-based inducements (such as tax rebates) are being tapped increasingly by state and local lawmakers who hope to encourage investment by these companies.

This cronyist activity is troubling for many reasons. As Brent and I will argue, tax credits and other benefits for digital technology companies are particularly misguided since (a) the most successful companies certainly don’t need them; and (b) the smaller companies or startups that might benefit from them today probably present a very risky investment for taxpayers. Many of these companies may be here today but gone tomorrow. That appears it could be the case for LivingSocial.

Tax credits can also become a time-consuming morass for innovators and distract them from the entrepreneurial activities they should be focused on. A recent Wall Street Journal report noted that “many companies are saying ‘no, thanks’ and are likely paying more taxes than legally required,” because “the tax deductions are either too cumbersome or too confusing. In some cases, the cost of obtaining the tax benefit is greater than the benefit itself.”

Policymakers should leave such risky investments to venture capitalists and others so that taxpayers are not on the hook when things go off the rails, just as they already have in DC with LivingSocial. Generally speaking, the best industrial recruitment / retention efforts are simple rules, low taxes, and light-touch regulation. That’s how to attract and retain a base of serious high-tech innovators without putting taxpayers at risk when things go wrong as they so often will in this sector.

Update: Shortly after I posted this piece I was contacted by representatives of the D.C. Mayor’s office asking me to clarify for readers that LivingSocial cannot claim any of these tax benefits unless it has 1,000 employees in city and unless it creates a 200,000 sq. ft. headquarters inside the District. They also asked me to again stress (as I noted in the opening paragraph) that these benefits will not begin until 2015-16. The exact terms of the deal can be found in the first link provided above (click the bill name).

In theory, such strings and stipulations could help the DC government escape this mess before it becomes an embarrassing fiasco for the city, but I would argue that they should not be putting taxpayers at risk like this to begin with. Moreover, while more strings might seem to provide greater accountability, added requirements and red tape also create more hassle and costs for firms. As I noted in my essay, that can affect future innovation and entrepreneurialism. Special deals for risky tech ventures remains unwise public policy.

November 26, 2012

Section 5 of the FTC Act and Monopolization Cases: A Brief Primer

Co-authored with Berin Szoka

In the past two weeks, Members of Congress from both parties have penned scathing letters to the FTC warning of the consequences (both to consumers and the agency itself) if the Commission sues Google not under traditional antitrust law, but instead by alleging unfair competition under Section 5 of the FTC Act. The FTC is rumored to be considering such a suit, and FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz and Republican Commissioner Tom Rosch have expressed a desire to litigate such a so-called “pure” Section 5 antitrust case — one not adjoining a cause of action under the Sherman Act. Unfortunately for the Commissioners, no appellate court has upheld such an action since the 1960s.

This brewing standoff is reminiscent of a similar contest between Congress and the FTC over the Commission’s aggressive use of Section 5 in consumer protection cases in the 1970s. As Howard Beales recounts, the FTC took an expansive view of its authority and failed to produce guidelines or limiting principles to guide its growing enforcement against “unfair” practices — just as today it offers no limiting principles or guidelines for antitrust enforcement under the Act. Only under heavy pressure from Congress, including a brief shutdown of the agency (and significant public criticism for becoming the “National Nanny“), did the agency finally produce a Policy Statement on Unfairness — which Congress eventually codified by statute.

Given the attention being paid to the FTC’s antitrust authority under Section 5, we thought it would be helpful to offer a brief primer on the topic, highlighting why we share the skepticism expressed by the letter-writing members of Congress (along with many other critics).

The topic has come up, of course, in the context of the FTC’s case against Google. The scuttlebut is that the Commission believes it may not be able to bring and win a traditional, Section 2 antitrust action, and so may resort to Section 5 to make its case — or simply force a settlement, as the FTC did against Intel in late 2010. While it may be Google’s head on the block today, it could be anyone’s tomorrow. This isn’t remotely just about Google; it’s about broader concerns over the Commission’s use of Section 5 to prosecute monopolization cases without being subject to the rigorous economic standards of traditional antitrust law.

Background on Section 5

Section 5 has two “prongs.” The first, reflected in its prohibition of “unfair acts or deceptive acts or practices” (UDAP) is meant (and has previously been used—until recently, as explained) as a consumer protection statute. The other, prohibiting “unfair methods of competition” (UMC) has, indeed, been interpreted to have relevance to competition cases.

Most commonly (and commonly-accepted), the UMC language has been viewed to authorize the agency to bring cases that fill the gaps between clearly anticompetitive conduct and the language of the Sherman Act. Principally, this has been invoked in “invitation to collude” cases, which raise the spectre of price-fixing but nevertheless do not meet the literal prohibition against “agreement in restraint of trade” under Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

Over strenuous objections from dissenting Commissioners (and only in consent decrees; not before courts), the FTC has more recently sought to expand the reach of the UDAP language beyond the consumer protection realm to address antitrust concerns that would likely be non-starters under the Sherman Act.

In N-Data, the Commission brought and settled a case invoking both the UDAP and UMC prongs of Section 5 to reach (alleged) conduct that amounted to breach of a licensing agreement without the requisite (Sherman Act) Section 2 claim of exclusionary conduct (which would have required that the FTC show that N-Data’s conducted had the effect of excluding its rivals without efficiency or welfare-enhancing properties). Although the FTC’s claims fall outside the ambit of Section 2, the Commission’s invocation of Section 5’s UDAP language was so broad that it could — quite improperly — be employed to encompass traditional Section 2 claims nonetheless, but without the rigor Section 2 requires (as the vigorous dissents by Commissioners Kovacic and Majoras discuss). As Commissioner Kovacic wrote in his dissent:

[T]he framework that the [FTC's] Analysis presents for analyzing the challenged conduct as an unfair act or practice would appear to encompass all behavior that could be called a UMC or a violation of the Sherman or Clayton Acts. The Commission’s discussion of the UAP [sic] liability standard accepts the view that all business enterprises – including large companies – fall within the class of consumers whose injury is a worthy subject of unfairness scrutiny. If UAP coverage extends to the full range of business-to-business transactions, it would seem that the three-factor test prescribed for UAP analysis would capture all actionable conduct within the UMC prohibition and the proscriptions of the Sherman and Clayton Acts. Well-conceived antitrust cases (or UMC cases) typically address instances of substantial actual or likely harm to consumers. The FTC ordinarily would not prosecute behavior whose adverse effects could readily be avoided by the potential victims – either business entities or natural persons. And the balancing of harm against legitimate business justifications would encompass the assessment of procompetitive rationales that is a core element of a rule of reason analysis in cases arising under competition law.

In Intel, the most notorious of the recent FTC Section 5 antitrust actions, the Commission brought (and settled) a straightforward (if unwinnable) Section 2 case as a Section 5 case (with Section 2 “tag along” claims), using the justification that it simply couldn’t win a Section 2 case under current jurisprudence. Intel presumably settled the case because the absence of judicial limits under Section 5 made its outcome far less certain — and presumably the FTC brought the case under Section 5 for the same reason.

In Intel, there was no effort to distinguish Section 5 grounds from those under Section 2. Rather, the FTC claimed that the limiting jurisprudence under Section 2 wasn’t meant to rein in agencies, but merely private plaintiffs. This claim falls flat, as one of us (Geoff) has noted:

[Chairman] Leibowitz’ continued claim that courts have reined in Sherman Act jurisprudence only out of concern with the incentives and procedures of private enforcement, and not out of a concern with a more substantive balancing of error costs—errors from which the FTC is not, unfortunately immune—seems ridiculous to me. To be sure (as I said before), the procedural background matters as do the incentives to bring cases that may prove to be inefficient.

But take, for example, Twombly, mentioned by Leibowitz as one of the cases that has recently reined in Sherman Act enforcement in order to constrain overzealous private enforcement (and thus not in a way that should apply to government enforcement). . . .

But the over-zealousness of private plaintiffs is not all [Twombly] was about, as the Court made clear:The inadequacy of showing parallel conduct or interdependence, without more, mirrors the ambiguity of the behavior: consistent with conspiracy, but just as much in line with a wide swath of rational and competitive business strategy unilaterally prompted by common perceptions of the market. Accordingly, we have previously hedged against false inferences from identical behavior at a number of points in the trial sequence.

Hence, when allegations of parallel conduct are set out in order to make a §1 claim, they must be placed in a context that raises a suggestion of a preceding agreement, not merely parallel conduct that could just as well be independent action. [Citations omitted].

The Court was appropriately concerned with the ability of decision-makers to separate pro-competitive from anticompetitive conduct. Even when the FTC brings cases, it and the court deciding the case must make these determinations. And, while the FTC may bring fewer strike suits, it isn’t limited to challenging conduct that is simple to identify as anticompetitive. Quite the opposite, in fact—the government has incentives to develop and bring suits proposing novel theories of anticompetitive conduct and of enforcement (as it is doing in the Intel case, for example).

Problems with Unleashing Section 5

It would be a serious problem — as the Members of Congress who’ve written letters seem to realize — if Section 5 were used to sidestep the important jurisprudential limitations on Section 2 by focusing on such unsupported theories as “reduction in consumer choice” instead of Section 2’s well-established consumer welfare standard. As Geoff has noted:

Following Sherman Act jurisprudence, traditionally the FTC has understood (and courts have demanded) that antitrust enforcement . . . requires demonstrable consumer harm to apply. But this latest effort reveals an agency pursuing an interpretation of Section 5 that would give it unprecedented and largely-unchecked authority. In particular, the definition of “unfair” competition wouldn’t be confined to the traditional antitrust measures — reduction in output or an output-reducing increase in price — but could expand to, well, just about whatever the agency deems improper.

* * *

One of the most important shifts in antitrust over the past 30 years has been the move away from indirect and unreliable proxies of consumer harm toward a more direct, effects-based analysis. Like the now archaic focus on market concentration in the structure-conduct-performance framework at the core of “old” merger analysis, the consumer choice framework [proposed by Commissioner Rosch as a cause of action under Section 5] substitutes an indirect and deeply flawed proxy for consumer welfare for assessment of economically relevant economic effects. By focusing on the number of choices, the analysis shifts attention to the wrong question.

The fundamental question from an antitrust perspective is whether consumer choice is a better predictor of consumer outcomes than current tools allow. There doesn’t appear to be anything in economic theory to suggest that it would be. Instead, it reduces competitive analysis to a single attribute of market structure and appears susceptible to interpretations that would sacrifice a meaningful measure of consumer welfare (incorporating assessment of price, quality, variety, innovation and other amenities) on economically unsound grounds. It is also not the law.

Commissioner Kovacic echoed this in his dissent in N-Data:

More generally, it seems that the Commission’s view of unfairness would permit the FTC in the future to plead all of what would have been seen as competition-related infringements as constituting unfair acts or practices.

And the same concerns animate Kovacic’s belief (drawn from an article written with then-Attorney Advisor Mark Winerman) that courts will continue to look with disapproval on efforts by the FTC to expand its powers:

We believe that UMC should be a competition-based concept, in the modern sense of fostering improvements in economic performance rather than equating the health of the competitive process with the wellbeing of individual competitors, per se. It should not, moreover, rely on the assertion in [the Supreme Court’s 1972 Sperry & Hutchinson Trading Stamp case] that the Commission could use its UMC authority to reach practices outside both the letter and spirit of the antitrust laws. We think the early history is now problematic, and we view the relevant language in [Sperry & Hutchinson] with skepticism.

Representatives Eshoo and Lofgren were even more direct in their letter:

Expanding the FTC’s Section 5 powers to include antitrust matters could lead to overbroad authority that amplifies uncertainty and stifles growth. . . . If the FTC intends to litigate under this interpretation of Section 5, we strongly urge the FTC to reconsider.

But it isn’t only commentators and Congressmen who point to this limitation. The FTC Act itself contains such a limitation. Section 5(n) of the Act, the provision added by Congress in 1994 to codify the core principles of the FTC’s 1980 Unfairness Policy Statement, says that:

The Commission shall have no authority under this section or section 57a of this title to declare unlawful an act or practice on the grounds that such act or practice is unfair unless the act or practice causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers which is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition. [Emphasis added].

In other words, Congress has already said, quite clearly, that Section 5 isn’t a blank check. Yet Chairman Leibowitz seems to be banking on the dearth of direct judicial precedent saying so to turn it into one — as do those who would cheer on a Section 5 antitrust case (against Google, Intel or anyone else). Given the unique breadth of the FTC’s jurisdiction over the entire economy, the agency would again threaten to become a second national legislature, capable of regulating nearly the entire economy.

The Commission has tried — and failed — to bring such cases before the courts in recent years. But the judiciary has not been receptive to an invigoration of Section 5 for several reasons. Chief among these is that the agency simply hasn’t defined the scope of its power over unfair competition under the Act, and the courts hesitate to let the Commission set the limits of its own authority. As Kovacic and Winerman have noted:

The first [reason for judicial reluctance in Section 5 cases] is judicial concern about the apparent absence of limiting principles. The tendency of the courts has been to endorse limiting principles that bear a strong resemblance to standards familiar to them from Sherman Act and Clayton Act cases. The cost-benefit concepts devised in rule of reason cases supply the courts with natural default rules in the absence of something better.

The Commission has done relatively little to inform judicial thinking, as the agency has not issued guidelines or policy statements that spell out its own view about the appropriate analytical framework. This inactivity contrasts with the FTC’s efforts to use policy statements to set boundaries for the application of its consumer protection powers under Section 5.

This concern was stressed in the letter sent by Senator DeMint and other Republican Senators to Chairman Leibowitz:

[W]e are concerned about the apparent eagerness of the Commission under your leadership to expand Section 5 actions without a clear indication of authority or a limiting principle. When a federal regulatory agency uses creative theories to expand its activities, entrepreneurs may be deterred from innovating and growing lest they be targeted by government action.

As we have explained many times (see, e.g., here, here and here), a Section 2 case against Google will be an uphill battle. As far as we have seen publicly, complainants have offered only harm to competitors — not harm to consumers — to justify such a case. It is little surprise, then, that the agency (or, more accurately, Chairman Leibowitz and Commissioner Rosch) may be seeking to use the less-limited power of Section 5 to mount such a case.

In a blog post in 2011, Geoff wrote:

Commissioner Rosch has claimed that Section Five could address conduct that has the effect of “reducing consumer choice” — an effect that a very few commentators support without requiring any evidence that the conduct actually reduces consumer welfare. Troublingly, “reducing consumer choice” seems to be a euphemism for “harm to competitors, not competition,” where the reduction in choice is the reduction of choice of competitors who may be put out of business by competitive behavior.

The U.S. has a long tradition of resisting enforcement based on harm to competitors without requiring a commensurate, strong showing of harm to consumers — an economically-sensible tradition aimed squarely at minimizing the likelihood of erroneous enforcement. The FTC’s invigorated interest in Section Five contemplates just such wrong-headed enforcement, however, to the inevitable detriment of the very consumers the agency is tasked with protecting.

In fact, the theoretical case against Google depends entirely on the ways it may have harmed certain competitors rather than on any evidence of actual harm to consumers (and in the face of ample evidence of significant consumer benefits).

* * *

In each of [the complaints against Google], the problem is that the claimed harm to competitors does not demonstrably translate into harm to consumers.

For example, Google’s integration of maps into its search results unquestionably offers users an extremely helpful presentation of these results, particularly for users of mobile phones. That this integration might be harmful to MapQuest’s bottom line is not surprising — but nor is it a cause for concern if the harm flows from a strong consumer preference for Google’s improved, innovative product. The same is true of the other claims. . . .

To the extent that the FTC brings an antitrust case against Google under Section 5, using the Act to skirt the jurisprudential limitations (and associated economic rigor) that make a Section 2 case unwinnable, it would be contravening congressional intent, judicial precedent, the plain language of the FTC Act, and the collected wisdom of the antitrust commentariat that sees such an action as inappropriate. This includes not just traditional antitrust-skeptics like us, but even antitrust-enthusiasts like Allen Grunes, who has written:

The FTC, of course, has Section 5 authority. But there is well-developed case law on monopolization under Section 2 of the Sherman Act. There are no doctrinal “gaps” that need to be filled. For that reason it would be inappropriate, in my view, to use Section 5 as a crutch if the evidence is insufficient to support a case under Section 2.

As Geoff has said:

Modern antitrust analysis, both in scholarship and in the courts, quite properly rejects the reductive and unsupported sort of theories that would undergird a Section 5 case against Google. That the FTC might have a better chance of winning a Section 5 case, unmoored from the economically sound limitations of Section 2 jurisprudence, is no reason for it to pursue such a case. Quite the opposite: When consumer welfare is disregarded for the sake of the agency’s power, it ceases to further its mandate. . . . But economic substance, not self-aggrandizement by rhetoric, should guide the agency. Competition and consumers are dramatically ill-served by the latter.

Conclusion: What To Do About Unfairness?

So, what should the FTC do with Section 5? The right answer may be “nothing” (and probably is, in our opinion). But even those who think something should be done to apply the Act more broadly to allegedly anticompetitive conduct should be able to agree that the FTC ought not bring a case under Section 5’s UDAP language without first defining with analytical rigor what its limiting principles are.

Rather than attempting to do this in the course of a single litigation, the agency ought to heed Kovacic and Winerman’s advice and do more to “inform judicial thinking” such as by “issu[ing] guidelines or policy statements that spell out its own view about the appropriate analytical framework.” The best way to start that process would be for whoever succeeds Leibowitz as chairman to convene a workshop on the topic. (As one of us (Berin) has previously suggested, the FTC is long overdue on issuing guidelines to explain how it has applied its Unfairness and Deception Policy Statements in UDAP consumer protection cases. Such a workshop would dovetail nicely with this.)

The question posed should not presume that Section 5′s UDAP language ought to be used to reach conduct actionable under the antitrust statutes at all. Rather, the fundamental question to be asked is whether the use of Section 5 in antitrust cases is a relic of a bygone era before antitrust law was given analytical rigor by economics. If the FTC cannot rigorously define an interpretation of Section 5 that will actually serve consumer welfare — which the Supreme Court has defined as the proper aim of antitrust law — Congress should explicitly circumscribe it once and for all, limiting Section 5 to protecting consumers against unfair and deceptive acts and practices and, narrowly, prohibiting unfair competition in the form of invitations to collude. The FTC (along with the DOJ and the states) would still regulate competition through the existing antitrust laws. This might be the best outcome of all.

Previous commentary by us on Section 5:

The Case Against the Section 5 Case Against Intel, Redux (January 2010)

Debunking the “Pro-business” Rationale for Section 5 Enforcement (February 2010)

FTC’s Misguided Rationale for the Use of Section 5 in Sherman Act Cases (February 2010)

What’s Really Motivating the Pursuit of Google? (June 2011)

Testimony on Balancing Privacy and Innovation: Does the President’s Proposal Tip the Scale? (March 2012)

The Folly of the FTC’s Section Five Case Against Google (May 2012)

[This is cross posted from Truth on the Market]

Conservatives and libertarians: We should move away from this kind of embarrassing rhetoric on copyright

I’ve come across another example of the kind of thinking and rhetoric on copyright that claims to be conservatives and libertarian, but which really does not serve the cause. I’m loathe to bring attention to it, but I think it’s important to start to renounce the kind of view that are often ascribed to conservatives and libertarians, but which don’t serve us and which only a tiny minority of us hold.

The piece in question is by Scott Cleland and it’s entitled “The Copyright Education of Mr. Khanna,” and like Tom Giovanetti before him, Cleland attacks Derek Khanna for his RSC policy brief. Cleland posits “five fundamental flaws” in Khanna’s argument. The first one is inscrutable, but if I can make out an argument it’s that Khanna is wrong because he’s questioning our existing copyright regime. I don’t see how questioning the status quo can make your argument flawed.

The second “fundamental flaw” Cleland points out is that “Mr. Khanna’s copyright views are not conservative.” He echoes Giovanetti by not addressing the merits of Khanna’s arguments but merely saying that if Khanna is agreeing with folks who are on the left, then there must be something with his argument. Cleland writes,

Mr. Khanna’s copyright views actually closely parrot the collectivist views of the famous Professor Larry Lessig who founded Free Culture and Creative Commons, championed Free Software and CopyLeft, and called for convening a new Constitutional Convention because “Democracy in America is stalled” by the “corruption” of money in politics.

It is also important to note that Marx and Engels said their theory could be summed up in one sentence: “Abolition of property.”

Do you see what just happened there? It’s the worst kind of guilt by association. First, while Khanna’s conclusions match Lessig’s, it’s not clear his reasoning can’t be distinguished. I know I can certainly distinguish my reasoning from Lessig’s in many instances. Folks on the left are more interested in equity, while libertarians are more interested in liberty and economic efficiency. The fact that we coincide on our conclusions on copyright should tell us that there’s something really wrong with out current system, not that we’re not “real conservatives.”

But never mind that, Cleland tries to link Khanna not just to Lessig’s views on copyright, but to his views on money in politics. And if that was not enough, there’s a non-sequitur about Marx and Engels and abolition of property to really drive the character assassination home.

The third flaw Cleland points out is that Khanna refers to copyright as a monopoly. This is wrong, Cleland says, because property can’t be a monopoly; after all, we don’t say you have a monopoly over your car, he says. He is right that the word monopoly is often misused, but the fact is that copyright, in an economic sense, is a grant of monopoly. In a world without copyright, creative expressions are non-rivalrous and non-excludable, unlike cars. We establish copyright in order to make expressions excludable. That is, we give creators market power where they had none before so that they may charge above marginal cost and thus have an incentive to create more than they otherwise would.

The fourth “flaw” that Cleland points out I can’t disagree with. It’s Khanna’s sentence, “Copyright violates every tenet of laissez faire capitalism.” I don’t think that’s right as written, but I also think Khanna wrote that for effect. Our current copyright system (as opposed to copyright as an idea) is certainly more crony capitalist than laissez faire capitalist.

Fifth, and finally, Cleland says that “Copyright is law not regulation.” Actually, as I pointed out in my last post, important parts of copyright are indeed administered through notice-and-comment regulation by the Copyright Office, not courts.

“In sum,” Cleland writes, “Mr. Khanna is promoting Lessigian anti-property thinking (that more American innovation and progress will emanate from the utopian altruism of a property-less system, where taking what others produce without permission is called ‘sharing),’ as superior to America’s Constitutional political and economic system of property and economic incentives.” This kind of rhetoric is exactly what has come from the more desperate and captured parts of the GOP for quite some time, and it should change for the sake of the GOP. It does not address the merits of arguments but instead tries to tar and feather innovative thinkers by asserting that if you’re for copyright reform then you must be against property, and thus a communist.

Don’t buy it folks. Criticism of our current copyright regime fits perfectly within an ideology that respects property rights. This is something that we make quite clear in our forthcoming book on copyright from a libertarian and conservative perspective. Khanna’s memo proposed a system that would grant authors a copyright term of 46 years. I don’t see how that is a “property-less system.”

November 24, 2012

The Pirate Party: Go Away, Please Come In

I find myself delighted, but also mildly disappointed, by a short speech making the rounds on the Internets, given by Amelia Anderstotter, Swedish Member of the European Parliament representing the Pirate Party. For its forcefulness, the speech misses a key distinction about which advocates of freedom, which I think members of the Pirate Party mean to be, should be very clear.

It’s a delightful speech because it’s a crisp rejection of the authoritarian forces that seek to control communications. In doing so, they hinder the development of culture. The woman delivering the speech is equal parts young, serious, and articulate. I reject authoritarianism, too, and I work to eliminate or hold at bay many of the same forces as Anderstotter, so that civil society can organize itself as it will.

I’m nonplussed, though, by the line that has gotten the speech so much attention.

“I would like to paraphrase George Michael from I think 1992,” she says. “‘Fuck you, this is my culture.’ And if copyright or telecommunications operators are standing in the way, I think they should go.’”

In one sense, the bracing language works. It is what generated a lot of interest in her words. But the context of the quote does not work as well. You see, when confronted with paparazzi photos showing him engaged in late-night cruising at a London park, Michael said, “Are you gay? No? Well then Fuck Off! Because this is my culture and you don’t understand it.” That is vituperation when confronted about arguably unhealthy behavior. It is not the conformity-rejecting line you might have expected in “Freedom! ’90,” presaging Michaels’ dispute with Sony over the release of Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 2.

One should certainly be free to act as Michael did among a community of consenting adults, and to reject criticism as he did. But when a speaker’s job is to persuade skeptics, one might choose an example of contempt for authority that the audience can easily embrace. With this quote, Anderstotter didn’t seat her rejection of authority firmly in logic and justice.

That’s a narrow point about influence, but the real weakness of the speech is in its internal logic. In the name of freedom, she calls for authoritarian regulatory interventions on private-sector network operators.

“[V]ery few top political figures in the world have acknowledged,” she says, that free speech and human rights protection “will require regulatory intervention on some private sectors.”

And later: “The control over communities and the ability to shape them must be with the communities themselves. Infrastructure must be regulated to enable that ability and such autonomy.”

Note how her use of passive voice hides the actor. Infrastructure “must be regulated” to achieve her agreeable goals. By whom? Perhaps one imagines beneficent gods fixing things up, but the regulations she seeks will almost certainly come from “the Governments and … public officials and lobbyists” that she says she wishes would fuck off.

A coherent system of rights does not have internal conflicts. If your freedoms come at the expense of someone else’s, you haven’t sorted out yet what “freedom” is.

Anderstotter is on the right track in many respects. Timid though the debate may be from her perspective, the scope and duration of copyright protection is again controversial among U.S. libertarians and conservatives. But her rejection of authoritarianism is an implicit embrace of authoritarianism at the same time.

With a little sorting out, she and the Pirate Party could get it right. Until then, the cultural reference she brings to mind for me is “meet the new boss, same as the old boss.”

November 21, 2012

The kind of thinking on copyright the GOP needs to move away from

Over at the IPI Policy Blog, Tom Giovanetti has a new post about “Copyright and the GOP” reflecting on the recent brouhaha over Derek Khanna’s retracted Republican Study Committee policy brief on copyright. I’m afraid Giovanetti’s post is a good example of exactly what’s wrong with the Republican status quo thinking and rhetoric on copyright.

The post begins by explaining why the GOP has “historically been strong supporters of copyright protections”:

Markets simply don’t work without property rights. You can’t have contracts, or licensing, if you don’t have clear and enforceable property rights. ALL business models, not just “new” business models, rest on property rights.

Further, because the GOP believes in innovation, copyright is a natural fit, because copyright incentivizes and encourages the creation, distribution and promotion of new information. The alternative to copyright isn’t free information, but less creation, less widely distributed and marketed.

Do you see what just happened there? The implication is that Khanna in his memo, or those of us who would like to see copyright reform, don’t think there should be copyright at all or don’t think that copyright is property. That’s just not the case. In his memo, for example, Khanna explicitly proposes up to 46 years of protection for creative works. That is copyright, and that is property, and it would allow for contracts and licensing and for markets to work.

When folks say that copyright reformers are anarchists who don’t believe in property rights, don’t buy it. It’s an inaccurate and unfair characterization.

Giovanetti goes on to write,

That’s why it was jaw dropping to see a paper appear on the Republican Study Committee (RSC) website that was infused with much of the rhetoric and many of the assumptions of the CopyLeft movement. When an RSC paper is praised on the Daily Kos website, you have to wonder what’s going on.

Rather than address the merits of Khanna’s memo, Giovanetti instead tries to make Khanna guilty by association. If some on the left agree with your ideas, the argument seems to go, then there must be something wrong with your ideas. This tribal mentality is exactly what the GOP should be trying to expunge right now. Isn’t it more likely that if your up-and-coming intellectuals agree with other thinkers on the left, then there may in fact be a problem worth addressing? It’s like saying John McCain or Marco Rubio are liberal radicals because they would agree with Ted Kennedy on immigration.

It gets worse. Giovanetti argues that there’s nothing to see here since the Copyright Office regularly reviews exemptions:

In the Information Age, copyright and patents have become focal points of much criticism. And it is both appropriate and necessary to review current laws and standards to ensure they reflect changes in the marketplace and in technology. Accordingly, the Copyright Office regularly releases new exceptions to copyright that reflect those changes.

Boy, how far we’ve come when it is argued that the GOP should be in favor of an unelected regulatory bureaucracy deciding what are our rights. As Matt Schruers recently wrote,

While I’m at peace with this, it continues to baffle me that more conservatives are not skeptical of expanding intellectual property. What is regulation, if not when bureaucrats hold an administrative rulemaking and issue a triennial rule dictating how individuals must conduct their affairs with respect to media they have already purchased? That sounds a lot like regulation to me.

What is regulation, if not when bureaucracies dispense exclusive entitlements to special petitioners intentionally designed to restrict competition, because it serves the broader purpose of incentivizing the pursuit and disclosure of particular creative activity? This is what our IP law does.

Don’t fall for it folks. Copyright reform is perfectly compatible with a strong belief in property rights and markets. More than that, opposition to our bloated copyright system that serves special interests in Hollywood at the expense of the public is in fact the true conservative and libertarian position.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower