Adam Thierer's Blog, page 55

October 21, 2013

Event Video: Cool vs. Creepy in Privacy Policy Debates

Here’s the video from a recent panel I sat on at the 4th annual Privacy Identity Innovation conference (pii2013) in downtown Seattle on September 17, 2013. The panel was entitled, “Emerging Technologies and the Fine Line between Cool and Creepy,” a topic I have written much about here in recent blog posts as well as in law review articles. The panel was expertly moderated by the awesome Natalie Fonseca, co-founder and executive producer of the pii2013 event as well as the always excellent Tech Policy Summit. Other panelists included Terence Craig, Co-founder and CEO, PatternBuilders and Co-author, Privacy and Big Data, Jamela Debelak, Technology and Liberty Director, ACLU of Washington, and my friend Larry Downes, Consultant and Author of The Laws of Disruption, among other excellent books. We discussed how to balance out the competing tensions surround new information technologies and stressed the various ways we could alleviate the primary concerns about many of them.

(The video, which is embedded down below, lasts just under 40 minutes. The audio is a little uneven because I was too stupid to keep the microphone close to my mouth. Sorry about that!)

Emerging Technologies and the Fine Line between Cool and Creepy from Privacy Identity Innovation on Vimeo.

October 16, 2013

On Facebook, Teens & Privacy

Facebook announced some changes to its site today that will make it easier for teen users to share content with not just their friends but also the entire world. (More coverage at The Washington Post here.) No doubt, some privacy advocates will cry foul and rush to policymakers with requests for restrictions. Yet, it’s not clear to me what their case would be. There isn’t any COPPA issue here since we are talking about teens, and they aren’t covered by the law. Moreover, it seems entirely sensible to allow teens to make their voices heard more broadly via Facebook’s platform the same way they can via many other online sites and services. Teens have speech rights, too, after all.

On the other hand, this is another “teachable moment” that parents should take advantage of. When sites (especially larger sites like Facebook) change their policies and make it easier for our kids to share more about themselves and their feelings, that is always a great time to have another chat with them about acceptable online behavior. I’ve spent a lot of time here and elsewhere talking about the importance of “Netiquette,” or proper online etiquette in various social settings and situations. We need to talk to our kids and each other about being more savvy, sensible, respectful, and resilient media consumers and digital citizens. And schools and even governments have a role to play in pushing education and media literacy in pursuit of better “digital citizenship.”

The crucial lesson here — and this certainly has relevance to today’s Facebook announcement — is that we need to constantly be encouraging our kids to think about smarter online hygiene (sensible personal data use) and proper behavior toward others. We can, without using excessive fear tactics, do more to explain the potential perils of over-sharing information about ourselves and others while simultaneously encouraging kids to delete unnecessary online information occasionally and cover their digital footprints in other ways. These efforts and lessons should start at a young age and continue on well into adulthood through other means, including awareness campaigns and public service announcements.

For its part, Facebook is taking the sensible step of issuing multiple warnings to teens before they use the new tools now at their disposal to communicate to the world. Before they first post publicly, they’ll apparently see an inline pop-up box warning them they are a posting for a broader audience than just their friends. I can’t see what more Facebook should do to educate kids in this regard. I suppose they could issue endless warnings each and every time that teens go to post publicly, but then the pop-up overload would just become annoying and drive kids away entirely.

Facebook also offers a lot of ways for users to clamp down on their sharing, but it defeats the whole purpose of the site if you are cranking all those settings up to maximum restrictiveness because, by its very nature, Facebook is all about sharing. So, we shouldn’t expect Facebook to switch all those defaults over to a completely locked-down experience.

If you don’t like the fact that your teen shares a lot on Facebook, you probably need to ask yourself if you want them on Facebook at all. Personally, Facebook is just not for me (I stopped using it well over a year ago; just too much of a Digital Nudist Colony for my taste) and my kids haven’t expressed much interest in it yet (which is probably good since they are not yet 13!) But if and when they do express interest (and are old enough to join), I will be happy to sit down with them, walk through the process of setting up a profile, and use the opportunity to talk to them in a open, understanding, and loving fashion about the ups and downs of digital life in a mass-sharing, hyper-transparent ecosystem like Facebook.

Honestly, as a parent, I don’t think Facebook is all that concerning from the perspective of safety, although it can at times be a bit more concerning when it comes to privacy. But many kids today aren’t even all that into Facebook and other social networking sites, viewing them as the spaces where old farts hang out. Today’s kids are more into visual media, texting, and services that let them instantaneously combine those services to rapidly create and share their lives and their feelings. My daughter and her friends walk around all day and night long filming each other and then creating silly mash-ups of the best moments before sharing them with each other and classmates. The potential for mistakes is always there and I am constantly talking to her about what she films, when she films, and who she shares the clips with. But in the end, she is being remarkably creative and enjoying herself immensely in the process. I want to encourage that since it is rewarding for both her and for me. I am very proud of what my kids can do with modern digital media and jealous that I did not have similar tools and opportunities when I was young! But I also want to make sure she understands the potential downsides and dangers of oversharing or inappropriate uses of modern video and texting technologies.

Patience and personal responsibility is always more sensible than panic. That’s something we should keep in mind when companies like Facebook and others role out new tools and features that our kids will gradually assimilate into their lives. Talk to them about it, help them make smart decision, and constantly reinforce those positive messages. But most of all, don’t panic!

Getting to the heart of the piracy debate

The launch of our new site PiracyData.org has predictably stirred up a good debate and I thought I’d chime in with a couple of thoughts. First I’d like to address the assertion by some, including Jeff Eisenach and Daniel Castro, that the point we’re trying to make with our site is that piracy is justified when content is not available legally. Here is Eisenach:

The Mercatus site is headlined by the following question: “Do people turn to piracy when the movies they want to watch are not available legally?” The implication is that piracy of movies that aren’t being offered legally is OK, or at least less bad, than piracy of movies that are currently available.

In both my post announcing the site and the Washington Post article Eisenach links to, as well as other articles about the site, I make it clear that there is no excuse for piracy. Piracy is illegal and wrong and copyright holders should be able to exercise their exclusive rights as they see fit during the term of copyright. I don’t know how much more explicit I can be. That said, although piracy is illegal and wrong, it may still be the case that the legal availability of content has an effect on piracy rates. That is a possibility that we are pointing out, not celebrating.

Second, I’d like to address the assertions by Eisenach and Castro that I am advocating that the movie industry should change its business model to collapse the theatrical release window, and that I think doing this will solve the piracy problem. Here again is Eisenach:

If you believe copyright holders have an obligation to make all content available to everyone all the time (as PiracyData.org seems to suggest), at what price would you require them to offer it?

In my post announcing the site I wrote that “their business model is their prerogative, and it’s none of my business to tell them how to operate,” and that’s something I repeated in other articles where I was quoted. So to be clear, I don’t think movie studios have any obligation to do anything. And I certainly don’t think that shortening their release windows would “eliminate piracy,” as Castro said.

Having addressed what I didn’t say, let me reiterate what I did say. The context for the creation of PiracyData.org was the MPAA report arguing that search engines were not taking sufficient voluntary measures to combat piracy. That study was released on the same day that the House held a hearing on “the role of voluntary agreements in U.S. intellectual property system” at which it was also argued that search engines, and Google in particular, have not done enough to combat piracy. The message from the content industry was, to echo Eisenach, that Google has an obligation to take all possible steps to end piracy. It is the nature of this notional obligation that we wanted to probe with PiracyData.org.

Hopefully I’ve been sufficiently clear that we all think that piracy is illegal and wrong and a problem that the content industry is rightfully up in arms about. So the question that we’re really debating is not whether piracy is right or wrong, but how to enforce copyright. How many resources should be expended, and by whom? That’s what this debate it really about.

Over a year ago, Google changed its algorithm to demote sites in its search results based on the number of copyright complaints those sites have received. An algorithmic change is as deep a change in a search engine’s business as one can expect. The message coming from the MPAA report and the House hearing, however, was that Google’s efforts were not enough, and that they should take further voluntary steps to not only remove infringing links from their search results, but also promote to the top legal sources.

PiracyData.org is never going to show all the ways that availability can affect piracy rates, and I’ve been clear about that both in my launch post and in interviews I’ve given, but I think that simply looking at the availability of the most-pirated movies will help shed some light on the simple question of whether people might turn to piracy when there is no legal version available. As the MPAA report noted, the majority of consumers who found themselves at infringing links “did not display an intention of viewing content illegally.” So the question is, why did these consumers who had no illegal intent end up at infringing sites? If they turned to piracy because they could not find a legal version, that would not justify piracy, but I hope we can all agree that it would be good to know whether it might be happening.

So it seems to me that we have identified two contentions of how piracy might be addressed. One is to have search engines voluntarily take more and more steps to change how they present the Web to users in order to address piracy. The other is that movie studios could shrink the theatrical release window. These are not mutually exclusive, and I think we see both happening. Google, as I mentioned, has already changed its algorithm and taken other measures, and as the MPAA has pointed out, the movie studios are working hard to make their movies available when and where consumers want. The question, therefore, is whether these efforts are enough or not, and what is the best way to enforce copyright.

Without a massive investment in enforcement, the sad reality is that piracy rates will never be zero. So what we should debate is whether additional enforcement efforts are worth the cost. As much as we might not want it to be the case, at some point there are diminishing marginal returns to more enforcement. If we determine that more could be done, then then the question is who should make that investment. Should it be search engines or the movies studios who should consider further changing how they do business?

Now, let me say that I am absolutely sympathetic to content owners who are put in incredibly unfair position of having to compete with piracy. As I said before, under the law they have the exclusive right to determine how they will distribute their works, and it is galling that they might feel forced by pirates to adopt a business model against their wishes. That is not fair to content owners. That said, the fact that they are facing this competition from piracy, as unfair and reprehensible as it is, is a fact that can’t be ignored.

In sum, these are the tough questions we should be discussing, not distractions about whether anyone is condoning piracy or whether anyone is blaming the victim, etc. We were hoping that PiracyData.org would spark that discussion, and boy have we had a big return on our investment! Now we need to make sure that we keep this debate on the serious and nuanced questions, and this is often hard to do over tweets and quotes in articles. So we are thinking of holding an event here at George Mason with all points of view represented to discuss these real questions. Stay tuned for details.

October 15, 2013

Launch Day Glitches at PiracyData.org

Today, we launched PiracyData.org, a site that takes the top ten most pirated movies of the week and mashes them up with data on legal online availability. Our hope is to build an extensive time-series dataset that can help shed light on the relationship between piracy and viewing options.

As might be expected with a new site, we’ve experienced some launch day glitches with the accuracy of our data and our visitors have thankfully pointed these out. We are of course committed to getting it right, so in the spirit of full transparency, we want to explain exactly what has gone wrong and how we plan on fixing it.

First, let me explain in detail how our site works and the exact data sources that we are using. Every hour, PiracyData.org polls the RSS feed for TorrentFreak’s most pirated movies posts. If the new week’s data is not yet in our database, we add it and fetch each movie’s availability from CanIStream.It.

CanIStream.It is a great site, but it is a little difficult for a computer to read. You can’t look up a movie by IMDB ID, which is pretty much the universal identifier for movies. What you can do, however, is pull up a CanIStream.It widget using IMDB ID.

The widget separates availability into four categories: streaming, rental, purchase, and physical DVDs. Given that this is a discussion of online piracy, we are really only interested in the first three categories, but we preserve all four. We scrape the page for movie availability on all of the services that the widget lists.

Making our site this way has presented us with four distinct issues that we only discovered once we started getting user feedback on the site:

1. Movie availability may change throughout the week

This is actually not a problem with our data, but with how it’s interpreted. Because the TorrentFreak data is backward-looking, reporting the most pirated movies in the previous week, we only want to report the online availability of movies as it appeared on Monday. That is, we are intentionally taking a snapshot of Monday availability. If movies become available for rental on Tuesday, we will continue to report throughout the remainder of the week that they were not available to rent on Monday, because that is most likely to reflect the state of the world during the preceding week when the piracy was happening.

A number of people have noted that Pacific Rim is now available for rental. We haven’t been able to confirm for sure, but we believe that it was added for rental at some point after we checked, and therefore this does not appear to be an error on our part. We’d appreciate it if anyone can confirm this because we want to make sure we are getting the right results.

2. Some services are available on CanIStream.It that are not listed in the widget, only on the main site

In particular, The Lone Ranger is available for rental only from a Sony service, but that service is absent in the CanIStream.It widget for not only The Lone Ranger but for all movies. Originally today, our site reported what the CanIStream.It widget reported, that the movie is not available for rental. However, when it was pointed out to us that CanIStream.It’s main site reports that The Lone Ranger is available on Sony, we updated our data to take account of that. We are going to find a way in the future to ensure that all services are automatically included in our dataset, but this means we may have to find another data source or resort to manual entry.

3. In at least one instance, CanIStream.It returned to us data for the wrong movie.

Here’s how the CanIStream.It widgets work: you go to the base url “http://www.canistream.it/external/imdb/” and add the IMDB ID for the movie you are querying. For example, since Pacific Rim’s ID is tt1663662, you can see the widget for the movie at http://www.canistream.it/external/imdb/tt1663662 .

This works perfectly most times, but bizarrely, it doesn’t work for This Is the End, whose IMDB is tt1245492. When you visit http://www.canistream.it/external/imdb/tt1245492 you get the CanIStream.It widget for Jay and Seth Vs. the Apocalypse, not This Is the End. As an outlier, this caught us totally by surprise, and we updated the data on our site to reflect the accurate data from This Is the End. Again, this is the kind of bug we could only have caught once we had lots of eyes on the site and we’re grateful for the feedback.

4. The site is built using the best available data.

TorrentFreak and CanIStream.It offer extremely useful data to the public. While we’ve had some issues incorporating the CanIStream.It data, we are grateful for the data they provide. CanIStream.It’s data is typically seen even among industry insiders as reliable. For instance, MPAA’s site wheretowatch.org directs their users to CanIStream.It as a source.

That said, if we want to build the canonical dataset on this issue, we have to do better. We need to make sure that there are no glitches. We would like to work with anyone with access to availability data to make sure that we can compile the most accurate data possible.

We’re not exactly sure what this entails yet. We may have to get availability data directly from the services themselves. If we can secure the cooperation of the services—for example if they would be willing to supply data on the date that each movie by IMDB number became available on their service—we could even compute availability data historically. TorrentFreak has data on pirated movies going back to 2006.

One thing is for certain: the dataset that we are proposing to build is important. We have provoked quite a reaction from people on both sides of this issue. We acknowledge that it has been a bumpy launch for our site, but we are committed to getting it right. We ask for everybody’s patience and good-faith assistance as we try to get there.

Are the most-pirated movies available legally online?

Today, Eli Dourado, Matt Sherman, and I launched PiracyData.org, a very simple site that tries to help answer the question, are the most-pirated movies each week available for legal streaming, digital rental, or digital purchase? We do this by mashing TorrentFreak’s weekly top-ten list of the most pirated movies on BitTorrent with Can I Stream It’s database of movie availability. The result if a single-page website that visualizes the results, as well as a downloadable dataset that will grow each week.

The idea for the site came to me last month when RIAA president Cary Sherman was testifying before Congress at a hearing on what further voluntary steps search engines could take to combat piracy. That same day, the MPAA had released a study that found that users who found themselves at URLs for infringing content had been “influenced” by search engines. This was reported in the press as “search engines lead to piracy.” The gist from the study and Sherman’s testimony was that search engines, and in particular Google, were not doing enough to address the fact that for some searches the top results include links to infringing content, and the implication, of course, is that if Google didn’t take voluntary action, perhaps Congress should require it to.

At the time I blogged an analysis of the MPAA study and noted that, according to the report, 58% of all visits to infringing URLs that were “influenced” by a search engine came from queries for either generic or title-based terms, not from the more-clearly suspicious “domain” terms. As the report remarked, this “indicat[es] that these consumers did not display an intention of viewing content illegally.” As I wrote at the time:

So the question is, why did these consumers who had no illegal intent end up at infringing sites? Could it be that they did not have a legal alternative to accessing the content they were seeking? That would not excuse their behavior, and it’s the movie industry’s prerogative whether and when to make their content available. Indeed release windows are part of its business model, although a business model seemingly in tension with consumer demand as evidenced by the shrinking theatrical release window. That all said, it’s not clear to me why search engines should be in the business of ensuring other industries’s business models remain unchanged.

After I wrote that it occurred to me that we could begin to collect data to answer that question, and so I asked Eli and Matt if they wanted to help me build the site. The initial answer the site is generating seems to be that very few are available legally.

To be clear, we only have three weeks of data so far, and we’ll get a better picture in the months ahead as the dataset grows. Additionally, proving the adage that given enough eyeballs all bugs are shallow, we’ve been alerted to the fact that a couple of the movies we were listing as unavailable this week are in fact available. Looking at the problem we found that although we were querying the correct IMDB ID for the movies, Can I Stream It was giving us back the wrong data. We’ve fixed the problem and updated the results. This is all to say that the site will prove its value a year from now when we have a substantial dataset.

That said, one implication of the early results may be that when movies are unavailable, illegal sources are the most relevant search results, so search engines like Google are just telling it like it is. That is their job, after all.

Also, while there is no way to draw causality between the fact that these movies are not available legally and that they are the most pirated, it does highlight that while the MPAA is asking Google to take voluntary action to change search results, it may well be within the movie studio’s power to change those results by taking voluntary action themselves. That is, they could make more movies available online and sooner, perhaps by collapsing the theatrical release window. Now, their business model is their prerogative, and it’s none of my business to tell them how to operate, but by the same token I I don’t see how they can expect search engines and Congress to bend over backwards to protect the business model they choose.

As we continue to debate what are the responsibilities of different actors in the Internet ecosystem related to piracy, we hope PiracyData.org will provide useful context.

October 9, 2013

“Not all that cybernet stuff, OK?”

Oh man, I could not stop laughing at this old “Kids Guide to the Internet” video from the 90s. My thanks to my former colleague Amy Smorodin for tweeting it out today. I just had to post it here so that everyone could enjoy.

(Note: You can turn this video into a great drinking game. Just make everyone in the room raise their glass each time the lines “Does your computer have a modem?” and “Not all that cybernet stuff, OK?” are uttered.) And yes, as the opening line of the video notes, “the first thing you need to know about the Internet is that it is amazing.”

October 8, 2013

Should California Rule the Internet?

Michelle Quinn of Politico was kind enough to call me a few days ago and ask for comment for her story about “California Driving Internet Privacy Policy.” Quinn’s article offers an excellent overview of how the Golden State is gradually taking on a greater regulatory role for the Net, at least as it pertains to matters of online privacy. She opens by noting that:

With the federal government and technology policy shut down in Washington, California is steaming ahead with a series of online privacy laws that will have broad implications for Internet companies and consumers.In recent weeks, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown has signed a litany of privacy-related legislation, including measures to create an “eraser button” for teens, outlaw online “revenge porn” and make Internet companies explain how they respond to consumer Do Not Track requests. The burst of activity is another sign that the Golden State — home to Google, Facebook and many of the world’s largest tech companies — is setting the agenda for Internet regulation at a time when the White House and Congress are moving at a much more glacial pace.

When she asked me how I felt about this, I noted that: “California seems like it is willing to declare the Internet its own private fiefdom and rule it with its own privacy fist.” And, no matter how well intentioned any of these new California policies may be, the ends most certainly do not justify the means.

As I noted in a January essay here on “The Perils of Parochial Privacy Policies,” such state-based meddling with the Internet and globally-interconnected networks and platforms raises profound constitutional issues. It threatens the free flow of commerce and speech. Even if it is the case that some of us may, at times, want some forms of commerce and speech limited by state action, I would very much hope that we could agree that having 50 states creating their own State Privacy Offices or State Data Protection Bureaus would probably not be a wise move. This is exactly the sort of thing that the Commerce Clause was put in place to protect against when interstate commerce is on the line. And it is also the sort of thing that might even be preemptable under the First Amendment since some speech issues are in play here. And I’m not even getting into the wisdom of some of the individual policies that California is pursing, many of which are highly impractical and likely extremely costly.

I hope that all those folks who say they really care about “Internet freedom” will make a stand against what California is doing here. But something leads me to believe that, once again, selective morality will enter the picture simply because of the sensitive and highly emotional nature of all online privacy and child safety issues. But, again, the ends do not justify the means. The Internet does not belong to California and they should not be allowed to make it their own regulatory fiefdom.

October 3, 2013

Why Did the FCC Adopt an Unusually High Reserve Price for the H Block Spectrum Auction?

It could be argued that the exact match between the DISH bid commitment and the H block reserve price is purely coincidental. To actually believe this was a coincidence would require the same willing suspension of disbelief indulged by summer moviegoers who enjoy the physics-defying stunts enabled by computer-generated special effects. When moviegoers leave the theater after watching the latest Superman flick, they don’t actually believe they can fly home.

The FCC’s Wireless Bureau recently adopted an unusually high $1.564 billion reserve price for the auction of the H block spectrum. Though the FCC has authorized the Bureau to adopt reserve prices based on its consideration of “relevant factors that could reasonably have an impact on valuation of the spectrum being auctioned,” it appears the Bureau exceeded its delegated authority in this proceeding by considering factors unrelated to the value of the H block spectrum that have the effect of giving a particular firm an advantage in the auction. Specifically, the Bureau considered the value to DISH Network Corporation of amendments to FCC rules governing other spectrum bands already licensed to DISH (e.g., the 700 MHz E block) in exchange for DISH’s commitment to meet the $1.564 billion reserve price in the H block auction – a commitment that is contingent on the FCC Commissioners amending rules governing multiple spectrum bands no later than Friday, December 13, 2013.

No matter what the FCC Commissioners decide, if the reserve price stands, the only sure winner would be DISH. If the FCC Commissioners don’t endorse the DISH deal, DISH need not honor its commitment to meet the artificially inflated reserve price, which could result in the spectrum auction’s total failure. If the Commissioners do endorse the DISH deal, the artificially inflated reserve price could deter the participation of other bidders and lower auction revenues that are expected to fund the national public safety network. Neither option would result in an open and transparent auction designed to provide all potential bidders with a fair opportunity to participate.

The FCC would be the only sure loser. The appearance of impropriety in the H block proceeding could compromise public trust in the integrity of FCC spectrum auctions. To ensure the public trust is maintained, the FCC Commissioners should thoroughly review the processes and procedures implemented by the Wireless Bureau in this proceeding before auctioning the H block spectrum.

The following discussion provides background information on the purposes of spectrum auctions and reserve prices. This background information is followed by a more detailed analysis of the terms of the DISH deal and the advantages it would bestow on DISH, the lack of analysis in the Wireless Bureau’s order, the role of the Commissioners, and the potential damage to the integrity of FCC auctions.

The Purpose of Spectrum Auctions

FCC spectrum auctions are intended to assign licenses to the firms that value the spectrum most highly, who are presumed to be most likely to provide the highest quality and most timely service to the public. Though this presumption was controversial when Congress first authorized spectrum auctions in 1993, twenty years and eighty-two auctions later, there is widespread agreement that open and transparent auctions have generally succeeded in licensing spectrum to the most efficient firms while minimizing delays in service to the public, preventing unjust enrichment, and providing revenue to the public treasury. Like any other market-based mechanism, however, competitive bidding mechanisms are vulnerable to market distortions. When the rules governing a spectrum auction are likely to produce market distortions, it weakens the presumption that the resulting auction is likely to award spectrum licenses to the most efficient firms.

The Purpose of Reserve Prices

The FCC has previously concluded that artificially inflated reserve prices are likely to result in market distortions.

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 established a presumption requiring the FCC to impose minimum opening bids or reserve prices in FCC auctions unless it is not in the public interest. (See FCC 97-413 at ¶ 139) Traditionally, reserve prices are used to maximize auction revenue and cannot be lowered once an auction begins. In its order implementing the Balanced Budget Act, the FCC determined that the minimum opening bid/reserve price requirement was not intended to require traditional reserve prices designed to maximize auction revenue – the provision was intended only as protection against assigning spectrum licenses at unacceptably low prices. (See id. at ¶ 140) The FCC thus directed the Wireless Bureau to consider only “relevant factors that could reasonably have an impact on valuation of the spectrum being auctioned” when establishing reserve prices. (See id. at ¶ 141 (emphasis added))

It is implicit in this delegation of authority that the Wireless Bureau cannot consider factors that are irrelevant to the valuation of the spectrum being auction. As the Bureau has previously recognized, establishing reserve prices based on factors that are unrelated to the valuation of the spectrum being auctioned could artificially inflate reserve prices, which could deter bidders from participating in the auction and preclude the assignment of the spectrum to the most efficient firms. (See DA 97-2147 at ¶¶ 13-14)

Despite its lack of delegated authority to do so, it appears that the Wireless Bureau considered irrelevant factors that may have artificially inflated the reserve price in the H block auction, including the value to DISH Network Corporation of amendments to FCC rules governing other spectrum bands already licensed to DISH. There is no rational (let alone reasonable) relationship between amendments to rules governing other spectrum bands that are uniquely valuable to a particular firm and the value of the H block spectrum generally. The Bureau nevertheless considered the unique interests of DISH while playing a larger game of Let’s Make a Deal involving otherwise unrelated FCC proceedings.

The Deal with Dish

The terms of the deal with DISH were memorialized in an ex parte letter (DISH Letter) filed by DISH in WT Docket No. 12-69 (“Promoting Interoperability in the 700 MHz Commercial Spectrum”) on September 10 (three days before the Wireless Bureau issued its order establishing the H block reserve price), and a petition for waiver (DISH Petition) filed by DISH on September 9 (which has not yet been assigned a docket number). According to these deal documents, DISH agreed to:

Consent to a reduction in the power limits currently applicable to its E block spectrum in the lower 700 MHz band (see DISH Letter at 2-3); and

Bid “at least a net clearing price equal to any aggregate nationwide reserve price established by the Commission in the upcoming H Block auction (not to exceed the equivalent of $0.50 per MHz/POP [i.e., $1.564 billion])” in order “to provide critical funds for FirstNet.” (DISH Petition at 2)

DISH stated that its consent and bid commitment are “contingent” on FCC actions to:

Extend DISH’s buildout deadlines in both the lower 700 MHz E block and the AWS-4 band; and

Authorize DISH to operate its AWS-4 spectrum in the 2000-2020 MHz band, which currently must be used only as uplink, as either uplink or downlink. (See DISH Letter at 2-3)

In the DISH Letter, DISH stated its “anticipat[ion] that the Commission will adopt a final order effectuating these changes no later than December 31, 2013,” including the “grant in its entirety” of the DISH Petition. (See Dish Letter at 2-3 (emphasis added)) In the DISH Petition, DISH stated that the FCC must adopt an order effectuating these changes “at least 30 days prior to the commencement of the H Block auction,” or its $1.564 billion bid commitment “shall no longer apply.” (See DISH Petition at 15) After the DISH Petition was filed, the Wireless Bureau ordered the H block auction to commence on January 14, 2014, which means DISH’s bid commitment applies only if the FCC Commissioners grant the DISH Petition in its entirety and modify the rules governing the 700 MHz E block no later than Friday, December 13, 2013.

Despite the fact that the deal gives the FCC Commissioners less than three months to grant DISH’s desires, DISH would have two and one-half years from the date the DISH Petition is granted to file an election stating whether it would deploy the 2000-2020 MHz band for downlink or uplink. (See DISH Petition at 1-2)

The Advantages Bestowed on Dish

If DISH were given the ability to elect whether to deploy the 2000-2020 MHz band for downlink or uplink for nearly two and one-half years after the H block auction concludes, DISH would have a substantial advantage in the auction relative to other potential bidders.

A discussion of the relationship between the H block and the AWS-4 spectrum and previous industry positions regarding this relationship is informative when analyzing the advantages bestowed on DISH and how it could affect the strategies of other potential bidders.

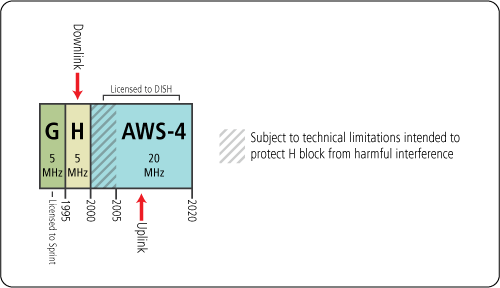

The current uplink requirement in the AWS-4 spectrum at 2000-2020 MHz and the downlink requirement in the adjacent H block spectrum at 1995-2000 MHz creates “particularly difficult technical issues” that “affect the use and value” of these bands. (See FCC 12-151 at ¶¶ 53, 65 (AWS-4 Order)) The deployment of downlink and uplink in adjacent bands increases the potential for harmful interference from out-of-band emissions (OOBE) and receiver blocking (or “overload”). (See AWS-4 Order at ¶ 72) In the AWS-4 proceeding, DISH argued that these interference issues meant the H block could not be auctioned at all and must be treated as a guard band (which would have eliminated most of its value). (See id. at ¶¶ 66, 69) The FCC chose to reduce the utility (and thus the value) of the AWS-4 spectrum instead by (1) increasing the OOBE limits applicable to the 2000-2020 MHz band, (2) limiting the power of mobile terrestrial devices in the 2000-2005 MHz portion of the AWS-4 band, and (3) requiring that DISH accept any OOBE and overload interference into that portion of the AWS-4 band caused by future, lawful operations in the H block. (See id. at ¶ 72) According to DISH, these restrictions render the 2000-2005 MHz portion of its AWS-4 spectrum unsuitable for mobile services.

In its order establishing service rules for the H block (H Block Order), the FCC noted that DISH had accepted the limitations on its AWS-4 spectrum and that “nothing [in the H Block Order was] intended to revisit these determinations.” (H Block Order, FCC 13-88 at ¶ 49) The FCC did, however, “specifically adopt . . . rules to adequately protect operations in adjacent bands, including the . . . 2000-2020 MHz AWS-4 uplink band.” (Id. at ¶ 48) These rules include a “more stringent OOBE limit of 70 + 10 log10 (P) dB, where (P) is the transmitter power in watts, for transmissions from the Upper H Block into the 2005-2020 MHz AWS-4 band.” (See id. at ¶ 59-60 (the FCC typically applies an OOBE limit of 43 + 10 log10 (P) dB at the edges of mobile bands only)) Sprint (who holds all of the licenses for the PCS G Block, which is contiguous with and complementary to the H block) had advocated for a less stringent limit of 60 + 10 log10 (P) dB across the 2005-2020 MHz band, and DISH (who holds all of the AWS-4 licenses) had advocated for an even more stringent 79 + 10 log10 (P) dB limit. (Id. at ¶ 65) The FCC split the difference, finding that an OOBE limit of 70 + 10 log10 (P) dB was “more consistent with the balancing of interference concerns between the AWS-4 and H Block bands discussed in the [AWS-4 Order]” than the less stringent limits proposed by Sprint and the more stringent limits proposed by DISH. (See id. at ¶ 68-73) The FCC also noted that licensees in the H block and the AWS-4 band could agree to modify the technical restrictions governing interference between these bands through private negotiation. (See AWS-4 Order at ¶ 73; H Block Order at ¶¶ 65, 208)

Relationship Between H Block & AWS-4 Spectrum

If the FCC Commissioners were to endorse the DISH deal, it would give DISH the unilateral ability to rebalance the interferences issues the FCC previously considered and resolved in its 2012 AWS-4 Order and its 2013 H Block Order – a unilateral ability that DISH could choose to exercise after the H block auction concludes. This would create a significant information asymmetry between DISH and all other potential bidders in the H block auction, which would improve DISH’s bidding position relative to other firms and potentially deter their participation in the auction. For example, if DISH were to elect to use the AWS-4 spectrum for downlink, it would mitigate the interference concerns that currently exist between the H block and ASW-4 bands, which would tend to increase the value of the H block to all potential bidders. Because DISH would have the unilateral ability to stall its election for nearly two and one-half years after the H block auction ends, however, DISH would be uniquely positioned to accurately assess the probability that it would choose to mitigate interference concerns by electing the downlink option. In these circumstances, other firms are likely to discount or ignore entirely whatever increase in value they would otherwise accord to the H block spectrum based on the mere possibility that DISH could elect to limit the 2000-2020 MHz band to downlink transmissions.

The proposed downlink election would also give DISH leverage in subsequent interference negotiations between itself and future H block licensees, which would tend to lower the bids of other firms while simultaneously limiting DISH’s incentive to bid any higher on the H block spectrum than its commitment would otherwise require. Assume, for example, that DISH meets its commitment by bidding the $1.564 billion reserve price but is subsequently outbid by Sprint. In the absence of the proposed election right, DISH would have an incentive to raise its previous bid because, if DISH owned both the H block and the AWS-4 spectrum, it could unilaterally eliminate the technical restrictions on both bands through private agreement with itself (a common practice when a single licensee owns spectrum across multiple blocks or bands). With the downlink election right, however, DISH’s incentive to bid on the H block in order to mitigate interference would be substantially diminished, because DISH could use its election right as leverage in post-auction interference mitigation negotiations with Sprint.

For example, assuming Sprint wins the H block, it would have an incentive to seek DISH’s agreement to the less stringent OOBE limits Sprint sought, but did not obtain, in the H block rulemaking proceeding. DISH likewise would have an incentive to seek Sprint’s agreement to technical parameters that would allow DISH to use the 2000-2005 MHz portion of the AWS-4 band for mobile services, which is something DISH sought, but did not obtain, in the AWS-4 and H block rulemaking proceedings. Because the downlink election would mitigate the interference concerns the FCC was required to balance in these rulemaking proceedings, it is possible DISH could use the election right to rebalance the technical rules in its favor (and thus increase the value of its AWS-4 spectrum) without paying for the H block spectrum at auction or paying to obtain the agreement of the H block licensees (in this hypothetical, Sprint). This possibility would tend to lower the price DISH would be willing to pay for the H block spectrum at auction while giving Sprint and other potential bidders incentives to discount their bids to account for the potential costs of their subsequent interference negotiations with DISH.

In effect, endorsing the DISH deal would provide DISH with an implicit government subsidy for its anticipated interference negotiations, the cost of which would be borne by the government (and, ultimately, public safety) in the form of lower auction revenues for the H block, which would tend to explain the Bureau’s decision to adopt the unusually high H block reserve price proposed by DISH.

The Lack of Analysis

Despite the obvious connection, the Wireless Bureau did not cite the DISH Letter or DISH Petition in its order adopting DISH’s minimum bid commitment as the reserve price for the H block auction. The Bureau didn’t discuss the DISH deal at all. It instead cited a brief ex parte letter (DISH Ex Parte) filed by DISH in the H block auction proceeding (AU Docket No. 13-178) on the same day DISH separately filed the DISH Petition (which has not yet been assigned a docket number).

The DISH Ex Parte also neglects to mention the DISH Petition filed that same day or the deal memorialized in the DISH Letter filed in WT Docket No. 12-69 the following day. The DISH Ex Parte addresses the reserve price issue in a single paragraph, which states only that “DISH estimates that the value of the H Block is at least $0.50 per” MHz-Pop on a nationwide aggregate basis (i.e., $1.564 billion) based on recent auctions and secondary market sales. (See DISH Ex Parte at 1 (citing the 2006 AWS-1 auction, the Verizon SpectrumCo transaction, and a Morgan Analyst Report)). Though it states the value of the H block is “at least” $1.564 billion, the DISH Ex Parte does not offer any analysis indicating that this estimate is an appropriate reserve price based on factors considered relevant by the FCC when establishing reserve prices – and neither does the Wireless Bureau’s order.

As noted above, the FCC has determined that reserve prices should be used only as protection against assigning licenses at unacceptably low prices and not as a tool to maximize auction revenue. In its order delegating authority to the Wireless Bureau to establish minimum opening bids or reserve prices, the FCC directed the Bureau to consider “the amount of spectrum being auctioned, levels of incumbency, the availability of technology to provide service, the size of the geographic service areas, issues of interference with other spectrum bands, and any other relevant factors that could reasonably have an impact on valuation of the spectrum being auctioned.” (See FCC 97-413 at ¶ 141) The Wireless Bureau didn’t discuss any of these factors in its order adopting the H block reserve price or find that a lesser amount would be “unacceptably low” (which seems unlikely given the more stringent technical limitations imposed on the H block in order to mitigate its “particularly difficult technical issues”). The Bureau simply concluded without analysis that the amount of DISH’s bid commitment is “appropriate” given the Spectrum Act’s requirement to use the auction proceeds for public safety purposes. (See DA 13-1885 at ¶ 172) The reasons why the Bureau believes this particular amount is appropriate were left unstated.

Though the FCC has occasionally adopted relatively high reserve prices in the past, they were expressly based on the potential value of the spectrum being auctioned or statutory incumbency issues. For example, in Auction 66, the FCC adopted a relatively high reserve price to ensure the auction raised enough revenue to relocate incumbent federal spectrum users as required by statute. The FCC also adopted relatively high reserve prices in Auction 73 because it was concerned that the unique public interest obligations and stringent buildout requirements it had imposed on that spectrum could result in unacceptably low auction prices. Safeguarding against the assignment of spectrum at unacceptably low prices due to factors relevant to the valuation of the spectrum being auctioned is the purpose the reserve price requirement is intended to serve.

As noted above, however, the FCC has concluded that it is inappropriate to adopt a high reserve price merely to maximize revenue (no matter how noble the cause) or to serve purposes unrelated to the spectrum being auctioned, because reserve prices adopted for such reasons are more likely to result in a failed auction. The irony in this instance is that, if the unusually high reserve price makes it more likely that the H block auction could fail, public safety could be worse off than if there were no reserve price at all. It is also ironic that DISH’s bid commitment is itself evidence that the reserve price adopted by the Bureau is artificially inflated. If the H block spectrum were actually worth “at least” as much as DISH estimates (and DISH were actually interested in winning it), DISH would not have had a legitimate reason to make its H block bidding commitment contingent on the FCC granting “in its entirety” the relief sought by DISH.

The unusually high reserve price placed on the H block spectrum is especially troubling given the obvious implication that the Bureau’s decision was driven primarily by factors unrelated to either the value of the H block or the interests of public safety – i.e., it appears the Bureau was motivated by the DISH deal’s role in resolving interoperability issues in the 700 MHz band. Though that is undoubtedly a noble goal, it is ignoble to achieve it by compromising the integrity of an unrelated spectrum auction.

It could be argued that the exact match between the DISH bid commitment and the H block reserve price is purely coincidental. The Bureau’s failure to mention that DISH had concurrently filed a petition committing to bid an amount identical to its suggested reserve price is not, however, enough to satisfy a claim of coincidence that meets the straight face test. To believe this was a coincidence would require the same willing suspension of disbelief indulged by summer moviegoers who enjoy the physics-defying stunts enabled by computer-generated special effects. When moviegoers leave the theater after watching the latest Superman flick, they don’t actually believe they can fly home.

The Role of the Commissioners

The particular process followed by the Wireless Bureau in this instance creates additional risk that the auction could fail and leave public safety with no revenue from the H block.

The Bureau’s adoption of an unusually high reserve price was presumably premised on the notion that, even if the reserve price is artificially inflated, there is little risk that the H block auction would fail because DISH committed to meet the reserve price. The problem with this premise is that DISH’s commitment is contingent on the FCC Commissioners agreeing to grant DISH specific relief before the auction, a decision that is outside the Bureau’s control. If the full FCC chooses to deny the DISH Petition and other rules changes sought by DISH, or simply fails to act within the requisite time, the H block auction may have to proceed with an artificially inflated reserve price and without any commitment by DISH to meet it.

In these circumstances, the Bureau’s decision to adopt an unusually high reserve price also has the effect of placing inappropriate pressure on the FCC Commissioners to act in accordance with the will of the Bureau. If the H block auction procedures stand, the options of the Commissioners would appear to be limited to (1) endorsing the DISH deal or (2) risking the failure of the H block auction due to the unusually high reserve price, which could in turn delay the payment of auction revenue slated for use by public safety. The Wireless Bureau’s decision thus has the effect of forcing the Commissioners into making a Hobson’s choice.

Given that the H block reserve price is based on considerations that lie outside the scope of the Bureau’s delegated authority, the reserve price should only have been approved (if at all) by a full FCC vote after a thorough analysis of its potential impact. In no event should the Bureau have adopted DISH’s proposed reserve price without a reasonable opportunity for comment by the public and thorough consideration by the Commissioners, especially given its potential impact on other spectrum bands.

The Integrity of FCC Auctions

The process for adopting the reserve price in the H block proceeding begs the question: Was this intended to be an open and transparent auction designed to assign H block licenses to the firms that value them most highly or a privately negotiated retail sale designed to ensure a minimum level of auction revenue while accomplishing unrelated policy goals that also benefit a particular firm? No matter the answer, the fact that this question must be asked is enough to compromise the public’s trust in the ability and willingness of the FCC to conduct open and transparent spectrum auctions that provide all potential bidders with a fair opportunity to participate. To restore public trust in the integrity of FCC auctions, the Commissioners should thoroughly review the Wireless Bureau’s competitive bidding processes and procedures before auctioning the H block spectrum.

October 2, 2013

Some quick thoughts on Silk Road’s demise and what it means for Bitcoin

As you know doubt have heard, Silk Road has been shut down by the FBI and its alleged operator, Ross Ulbricht, has been arrested. I've been getting a lot of questions about this and what it means for Bitcoin. Here are some initial thoughts.

The price of Bitcoin is dropping. What does that mean? It means that speculators are speculating. That said, here's how I'm going to read it: If the main value of Bitcoin is that it can be used to buy drugs on Silk Road (as some contend), then we should see the value drop to zero is short order. If Bitcoin has other value, we should see it weather this jolt. One year ago a Bitcoin traded for about $14. As I type this, it's hovering at about $118 $127.

How did they catch the guy? Good question. I don't know the answer, but that won't stop me from speculating. I will point out two things. First is this from the criminal complaint against Ross Ulbricht:

During the course of this investigation, the FBI has located a number of computer servers, both in the United States and in multiple foreign countries, associated with the operation of Silk Road. In particular, the FBI has located in a certain foreign country the server used to host Silk Road's website (the "Silk Road Web Server"). Pursuant to a mutual Legal Assistance Treaty request, an image of the Silk Road Web Server was made on or about July 23, 2013, and produced thereafter to the FBI.

OK. So how did the FBI "locate" the servers that hosted the Silk Road Tor hidden service? The FBI has recently admitted that they have exploited vulnerabilities in Tor to identify users. Could it be that they exploited some vulnerability in this case? I look forward to finding out.

That said, here is another possibility. Also according to the criminal complaint (emphasis added),

On or about July 10, 2013, [Customs and Border Patrol] intercepted a package from the mail inbound from Canada as part of a routine border search. The package was found to contain nine counterfeit identity documents. Each of the counterfeit identification documents was in a different name yet all contained a photograph of the same person.

That person was Ulbricht and the package was addressed to him. Maybe it was from this lead that the FBI was able to begin the process of identifying the servers, once they had a suspect. If so, and if this indeed was a "routine" search, then the authorities got completely lucky!

Finally, I'll point out that Bitcoin was in no way involved in the identification of the suspect. In fact, in the criminal complaint the FBI argues that because the blockchain (Bitcoin's public ledger) is pseudonymous, that it is not useful in tracing transactions. I don't think that's quite right, but that's how the FBI sees it in this case. So, in this case at least, the privacy Bitcoin affords was not compromised in any way.

UPDATE: As I think about this some more, it's clear that the FBI was able to identify Ross Ulbricht because he posted his Gmail address to the Bitcoin Talk forum using the same username that first mentioned Silk Road ever. So, what are the chances that the CPB search that turned up the package of fake IDs bound for Ulbricht was routine? If it was routine, it was routine in the sense that packages to people on a watchlist might be routinely searched. I'm still not clear how the FBI got from identifying a possible suspect to locating the server for the Silk Road Tor hidden service.

How do you seize Bitcoins? I'm surprised by how many times I've been asked this question. It's amazing what it is that people seize upon in a story. < cough > I don't know how the authorities have carried out the seizure, but it's not to difficult to conceive how it could be done. Basically they would have to get the private keys to the suspect's Bitcoin addresses. (Think of it essentially like getting the password to an account.) They could either get that with his cooperation or if he had stored it somewhere now accessible to the authorities. Once they have the private keys, they would be able to transfer the bitcoins and I imagine that they would transfer them to a Bitcoin address that only they control.

UPDATE: So I got ahold of the seizure order and indeed I was correct that this is how the government will try to go about seizing the bitcoins. From the court order:

The United States is further authorized to seize any and all Bitcoins contained in wallet files residing on Silk Road servers, including those servers enumerate in the caption of this Complaint, pending the outcome of this civil proceeding, by transffering the full account balance in each Silk Road wallet to a public Bitcoin address controlled by the United States.

But to be clear, to seize bitcoins you do need to get the "password" that controls them. You can't just go to an intermediary and order that an account be frozen as you can do with traditional financial intermediaries like banks or PayPal.

I'll be tweeting and posting more as I learn more about what happened, but those are my initial thoughts. Shoot me any questions or thoughts you have. I'm at @jerrybrito on Twitter. And by the way, you can follow all the coverage of the Silk Road arrest and seizure on my site Mostly Bitcoin.

The FTC should provide ammo for software patent abolitionists

Last week, the FTC proposed to use its Section 6(b) power to investigate patent trolls. Its clear from the agency’s comment request that what they’re really interested in examining is the practice of patent privateering.

For The Umlaut, I wrote an article explaining what patent privateering is and how it upsets the fragile state of affairs in the software industry.

Because patent trolls are non-practicing, they are not subject to threats of counter-suit and mutually assured destruction. Because they are not members of any SSOs, they do not have any obligation to license on a FRAND basis; standard-essential patents can be transferred to privateers and then asserted against all users of the standard. And because the transfer of patents to patent trolls is often done through various shell companies or other shadowy means, the defendant and the public often cannot know on which practicing software company’s behalf the privateer is working. This means the defendant cannot retaliate through countersuits or a public relations offensive.

I think that understanding how patent privateering actually works and how it disrupts companies’ attempts to innovate makes one much more sympathetic to simply abolishing software patents outright. Given that the practice is not widely understood, the FTC could add value by simply disseminating information about it to a wider audience. I don’t think that the FTC has the authority to regulate patent enforcement, since patent rights are explicitly authorized by Congress, but they can and should send Congress the message that software patents are being used to stifle innovation, not promote it.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower