Adam Thierer's Blog, page 101

February 21, 2012

When an Idea Become a Meme, and Why

Ceci c'est un meme.

Ceci c'est un meme.On Forbes today, I look at the phenomenon of memes in the legal and economic context, using my now notorious "Best Buy" post as an example. Along the way, I talk antitrust, copyright, trademark, network effects, Robert Metcalfe and Ronald Coase.

It's now been a month and a half since I wrote that electronics retailer Best Buy was going out of business…gradually. The post, a preview of an article and future book that I've been researching on-and-off for the last year, continues to have a life of its own.

Commentary about the post has appeared in online and offline publications, including The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, TechCrunch, Slashdot, MetaFilter, Reddit, The Huffington Post, The Motley Fool, and CNN. Some of these articles generated hundreds of user comments, in addition to those that appeared here at Forbes.

(I was also interviewed by a variety of news sources, including TechCrunch's Andrew Keen.)

Today, the original post hit another milestone, passing 2.9 million page views.

Watching the article move through the Internet, I've gotten a first-hand lesson in how network effects can generate real value.

Network effects are an economic principle that suggests certain goods and services experience increasing returns to scale. That means the more users a particular product or service has, the more valuable the product becomes and the more rapidly its overall value increases. A barrel of oil, like many commodity goods, does not experience network effects – only one person can own it at a time, and once it's been burned, it's gone.

In sharp contrast, the value of networked goods increase in value as they are consumed. Indeed, the more they are used, the faster the increase–generating a kind of momentum or gravitational pull. As Robert Metcalfe, founder of 3Com and co-inventor of Ethernet explained it, the value of a network can be plotted as the square of the number of connected users or devices—a curve that approaches infinity until most everything that can be connected already is. George Gilder called that formula "Metcalfe's Law."

Since information can be used simultaneously by everyone and never gets used up, nearly all information products can be the beneficiaries of network effects. Standards are the obvious example. TCP/IP, the basic protocol that governs interactions between computers connected to the Internet, started out humbly as an information exchange standard for government and research university users. But in part because it was non-proprietary and therefore free for anyone to use without permission or licensing fees, it spread from public to private sector users, slowly at first but over time at accelerating rates.

Gradually, then suddenly, TCP/IP became, in effect, a least common denominator standard by which otherwise incompatible systems could share information. As momentum grew, TCP/IP and related protocols overtook and replaced better-marketed and more robust standards, including IBM's SNA and DEC's DECnet. These proprietary standards, artificially limited to the devices of a particular manufacturer, couldn't spread as quickly or as smoothly as TCP/IP.

From computing applications, Internet standards spread even faster, taking over switched telephone networks (Voice over IP), television (over-the-top services such as YouTube and Hulu), radio (Pandora, Spotify)—you name it.

Today the TCP/IP family of protocols, still free-of-charge, is the de facto global standard for information exchange, the lynchpin of the Internet revolution. The standards continue to improve, thanks to the largely-voluntary efforts of The Internet Society and its virtual engineering task forces. They're the best example I know of network effects in action, and they've created both a platform and a blueprint for other networked goods that make use of the standards.

Beyond standards, network effects are natural features of other information products including software. Since the marginal cost of a copy is low (essentially free in the post-media days of Web-based distribution and cloud services), establishing market share can happen at relatively low cost. Once a piece of software—Microsoft Windows, AOL instant messenger in the old days, Facebook and Twitter more recently—starts ramping up the curve, it gains considerable momentum, which may be all it takes to beat out a rival or displace an older leader. At saturation, a software product becomes, in essence, the standard.

From a legal standpoint, unfortunately, market saturation begins to resemble an illegal monopoly, especially when viewed through the lens of industrial age ideas about markets and competition. (That, of course, is the lens that even 21st century regulators still use.) But what legal academics, notably Columbia's Tim Wu, misunderstand about this phenomenon is that such products have a relatively short life-cycle of dominating. These "information empires," as Wu calls them, are short-lived, but not, as Wu argues, because regulators cut them down.

Even without government intervention, information products are replaced at accelerating speeds by new disruptors relying on new (or greatly improved) technologies, themselves the beneficiaries of network effects. The actual need for legal intervention is rare. Panicked interference with the natural cycle, on the other hand, results in unintended consequences that damage emerging markets rather than correcting them. Distracted by lingering antitrust battles at home and abroad, Microsoft lost momentum in the last decade. No consumer benefited from that "remedy."

For more, see "What Makes an Idea a Meme?" on Forbes.

David Weinberger on knowledge

On the podcast this week, David Weinberger, senior researcher at Harvard Law's Berkman Center for the Internet & Society and Co-Director of the Harvard Library Innovation Lab at Harvard Law School, discusses his new book entitled, "Too Big to Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That the Facts Aren't the Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, and the Smartest Person in the Room Is the Room." According to Weinberger, knowledge in the Western world is taking on properties of its new medium, the Internet. He discusses how he believes the transformation from paper medium to Internet medium changes the shape of knowledge. Weinberger goes on to discuss how gathering knowledge is different and more effective, using hyperlinks as an example of a speedy way to obtain more information on a topic. Weinberger then talks about how the web serves as the "room," where knowledge seekers are plugged into a network of experts who disagree and critique one another. He also addresses how he believes the web has a way of filtering itself, steering one toward information that is valuable.

Related Links

"Too Big to Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That the Facts Aren't the Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, and the Smartest Person in the Room Is the Room", by Weinberger"Research Ethics: Coercive Citation in Academic Publishing", Science Daily"Knowledge Has Always Been Networked: On Weinberger's 'Too Big to Know'", The Atlantic

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the webpage for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

February 19, 2012

Did Google Defeat People's Privacy Preferences?

Given the importance of privacy self-help—that is, setting your browser to control what it reveals about you when you surf the Web—I was concerned to hear that Google, among others, had circumvented third-party cookie blocking that is a default setting of Apple's Safari browser. Jonathan Mayer of Stanford's Center for Internet and Society published a thorough and highly technical explanation of the problem on Thursday.

The story starts with a flaw in Safari's cookie blocking. Mayer notes Safari's treatment of third-party cookies:

Reading Cookies Safari allows third-party domains to read cookies.

Modifying Cookies If an HTTP request to a third-party domain includes a cookie, Safari allows the response to write cookies.

Form Submission If an HTTP request to a third-party domain is caused by the submission of an HTML form, Safari allows the response to write cookies. This component of the policy was removed from WebKit, the open source browser behind Safari, seven months ago by Google engineers. Their rationale is not public; the bug is marked as a security problem. The change has not yet landed in Safari.

Mayer says Google was exploiting this yet-to-be-closed loophole to install third-party cookies, the domain of which Safari would then allow to write cookies. After describing "(relatively) straightforward" cookie synching, Mayer says:

But we noticed a special response at the last step for Safari browsers. … Instead of responding with the "_drt_" cookie, the server sends back a page that includes a form and JavaScript to submit the form (using POST) to its own URL.

Third-party cookie blocking evaded, and users' preferences frustrated.

Ars Technica has published Google's response, which doesn't seem to have gone up on any of its blogs, in full. Google says they created this functionality to deliver better services to their users, but doing so inadvertently allowed Google advertising cookies to be set on the browser.

I don't know that I'm technically sophisticated enough to register a firm judgement, but it looks to me like Google was faced with an interesting dilemma: They had visitors who were signed in to their service and who had opted to see personalized ads and other content, such as '+1′s but those same visitors had set their browsers contrary to those desires. Google chose the route better for Google, defeating the browser-set preferences. That, I think, was a mistake.

I wonder if there isn't some Occam's Razor that a Google engineer might have applied at some point in this process, thinking, "Golly, we are really going to great lengths to get around a browser setting. Are we sure we should be doing this?" Maybe it would have been more straightforward to highlight to Safari users that their settings were reducing their enjoyment of Google's services and ads, and to invite those users to change their settings. This, and urging Apple to fix the browser, would have been more consistent with the company's credo of non-evil.

Now, to the ideological stuff, of which I can think of two items:

1) There is a battle for control of earth out there—well, a battle over whether third-party cookie blocking is good or bad. Have your way advocates. I think the consuming public—that is, the market—should decide.

2) There is a battle to make a federal case out of every privacy transgression. An advocacy group called Consumer Watchdog (which has been prone to privacy buffoonery in the past) hustled out a complaint to the Federal Trade Commission. I think the injured parties should be compensated in full for their loss and suffering, of which there wasn't any. De minimis non curat lex, so this is actually just a learning opportunity for Google, for browser authors, and for the public.

Kudos and thanks are due to Jonathan Mayer, as well as ★★★★★ and Ashkan Soltani, for exposing this issue.

February 16, 2012

The FTC, Mobile Apps, Kids' Privacy, Prices & Competition

Today the Federal Trade Commission released a new report entitled, "Mobile Apps for Kids: Current Privacy Disclosures Are Disappointing," which concludes that "confusing and hard-to-find disclosures do not give parents the control that they need in this area. The FTC argues that "parents need consistent, easily accessible, and recognizable disclosures regarding in-app purchase capabilities so that they can make informed decisions about whether to allow their children to use apps with such capabilities."

It's hard to be against the FTC's "the more disclosure, the better" policy recommendation and I'm not about to come out against it here. But the question is: how much disclosure is enough? Reading through the report and seeing how hard the FTC hammers this point home makes me think the agency wants our app store checkout process to be littered with the pages of fine print disclosure policies that now accompany our credit card statements and home mortgage payments! Seriously, would that make us better off?

As a parent of two kids who both download countless apps on my Android phone, my wife's iPhone, and our family's Android tablet, I appreciate a certain amount of disclosure about what sort of information apps are collecting and how they are using it. I think Google's Android marketplace strikes a nice balance here, providing us with the most crucial facts about what the application will access or share. Apple could do more on disclosure but the company also prides itself (to the dismay of some!) on its rigorous pre-screening process to make sure the apps in the App Store are safe and don't violate certain privacy and security policies. Yet, as the FTC correctly points out, "the details of this screening process are not clear." Of course, most Apple users simply don't give a damn. They're all too happy to let Apple just take care of it for them even if they're not really sure what's happening to their data behind the scenes. The more privacy-sensitive crowd wants greater disclosure and control, of course, and I'm sympathetic to that plea. But again, how much disclosure is enough? Are you going to wade through pages of disclosure policies and privacy opt-ins before downloading that latest iteration of "Angry Birds" or "Cut the Rope"? Yeah, I didn't think so.

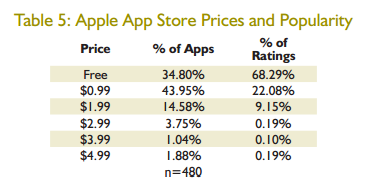

Anyway, I don't want to dwell on that. The more interested findings in the survey relate to price and market dynamics and I am hoping people don't ignore them. After surveying the price of kids' apps available in the Android Market and Apple App Store, the agency found that, "While prices ranged from free to $9.99, most of the 960 app store promotion pages listed a price of $0.99 or less. Indeed, 77% of the apps in the survey listed an install price of $0.99 or less, and 48% were free. Free apps appeared to be the most frequently downloaded." Here's the pricing breakdown for both Android and Apple:

Folks, these are astonishing numbers. Almost 100% of the most downloaded kids apps in the Android Market are free… as in ZERO dollars and ZERO cents! And while Apple App Store prices tend to be a bit higher, 93% of apps are $2 or less. This is one of the great consumer success stories of our time. Consumer welfare is vastly enhanced by the presence of hundred of kids apps that serve almost every interest and desire under the sun, and all for less than what you'd pay for a cup of coffee or a gallon of gas.

But wait, there's more!!

This incredible success story is even more remarkable because of what the FTC finds next about market structure:

Staff found that hundreds of developers were responsible for the apps in the study. Staff encountered 441 unique developers in this study, only twelve of which had apps on both platforms. Only a handful of app developers were responsible for more than 10 apps in our sample. Developers with one app in our sample were popular, accounting for about 50% of all downloads/feedback ratings, even though they were responsible for only about 30% of the apps. In contrast, those developers with more than 10 apps in our sample accounted for about 1% of the feedback ratings for Apple, (and 20% of the downloads for Android) despite accounting for about 20% of all of the apps in the survey. This finding illustrates the broad and diverse nature of the mobile app marketplace.

"Broad and diverse marketplace," you say? That might be the understatement of the year! I challenge you to find another part of not just our online ecosystem but indeed our entire economy that is this broad, diverse, innovate, competitive, and inexpensive. I'm not sure that such a radically atomistic, mom-and-pop marketplace of entrepreneurs can last forever, but let's pause and appreciate the fact that it does exist today.

Now, here's the really interesting part of this story: This is generally what the world of kids' online services looked like back in the late 1990s as well. It was incredibly diverse with lots of small mom-and-pop sites catering to kids and parents, often at no charge. And then along came COPPA. [Background here for those who are not familiar.] While COPPA helped address the legitimate problems a small handful of bad apples out there at the time created, it also raised serious compliance costs for that entire sector, including the many smaller mom-and-pop sites. In a letter send to the FTC back in 2005, child safety advocate Parry Aftab claimed that, "The cost of obtaining verifiable parental consent for interactive communications is very high, estimated at more than $45 per child, and even at that price difficult to obtain." I have no idea how accurate that number was then (I think that was way too high of an estimate), or what the compliance cost per child was in the late 1990s, but let's be conservative and say it was much smaller, perhaps less that a few bucks per child verified under COPPA. And let's assume that if we extended COPPA-like regulatory requirements to app stores that there would be some compliance cost. Again, even if the compliance cost was only a buck per kid, can you see how it devastating that would be to all the small mom-and-pop app developers out there who currently only get a dollar or two for their apps (assuming they charge anything at all)? Yes, it's true that some of them use ads to offset their costs, but those ads have to pick up the tab for all their labor and development costs. If you add new regulatory compliance costs to the mix, those mom-and-pop developers will be hit very hard. And then we will have far fewer of them. And the ones that remain will likely charge us more than the couple of bucks we pay per app today.

Further, even if the compliance cost per child gets down to a few cents (or tens of cents) per kid for large operators, it's probably much higher for smaller operators. In other words, most of the costs here are fixed (hiring an extra employee, having lawyers review your policy, etc.), not marginal (the cost of verifying each additional kid), so it's really hard to say what the real costs are. And with Apple and Google also taking a cut of the apps sold in the market, you really begin to see how adding on any additional compliance costs could hit the bottom lines of smaller app developers in a big way. When margins are this thin, burdensome regulatory mandates hurt even more. And sometimes they can drive you right out of business.

Which brings us back to the FTC's role here. It's clear that the consumer protection side of the agency has an important role to play here when it comes to ensuring consumers are better informed about data collection practices and corresponding privacy issues. But let's not forget that the FTC was originally created as a competition agency. It's supposed to care about market structure, competition, and consumer welfare. So, I wonder… are the folks in the FTC's Bureau of Economics paying any attention to what their colleague are doing here? Because if we start layering on privacy regulations, all the good intentions in the world won't be able to hold back the likely contraction and consolidation of this vibrant industry that will take place as small mom-and-pops struggle to absorb new regulatory burdens and compliance costs.

Something to think about before regulatory intervention drives up consumers prices and drives out of the market the countless entrepreneurs that make this sector so exciting–especially for parents and kids.

Some (hopefully constructive) thoughts on cybersecurity

Ahead of today's cybersecurity hearing in the Senate, I wanted to jot down some thoughts on the issue. For over a year now, I've been questioning the need for federal intervention in cybersecurity and calling for a slower and more deliberate process. Perhaps I come across as a refusenik, but I hope that I'm at least lending some balance to the debate.

First, let me say that I fully recognize that the U.S. faces serious cyber threats. Here is one of the best (and most honest) cases for being worried that I've seen. I get it.

That said, what I try to point out is that the existence of a threat does not necessarily mean that regulation is necessary. In many cases, the threat can be internalized by affected private actors. Even if we determine that some private actors are not internalizing the costs, prescriptive regulation can sometimes do more harm than good. The best thing we can do is not try to prevent harm at all costs, but instead make sure that we are resilient so that no single threat can destroy us. And we may be more anti-fragile–more resilient and more capable of adaptation–than we're led to believe.

That brings me to the other thing I try to point out: that the rhetoric surrounding cybersecurity is often unnecessarily alarmist. Introducing the Cybersecurity Act of 2012, Sen. Rockefeller equated the cyber threat with the nuclear threat. I'm sorry, but I don't think that's right. It does scare people, however, and I'm afraid that we will be sold an expensive bill of goods based on fear.

So I'm happy to see that both the Senate and the House have begun to take more realistic approaches to cybersecurity. For example, the Rockefeller-Snowe bill from last congress would have required the Department of Commerce to develop "a national licensing, certification, and periodic recertification program for cybersecurity professionals," and would have made certification mandatory for anyone engaged in cybersecurity. I'm happy to see that's gone in the new bill. I'm glad that there is no "Internet kill switch." I'm also happy to see that the bill includes a way for private industry to appeal its inclusion in the regulatory regime.

Where do I think there may be a role for government? Information sharing certainly comes to mind. There is no doubt that there's a lot that the public and private sectors can learn from each other. And to the extent that private actors are prevented by privacy laws to cooperate on cybersecurity, there should be a way to facilitate cooperation without endangering consumer protections. Additionally, requiring disclosure of security breaches is not a bad idea. It would allow insurance markets and other markets serve as an alternative to regulation, or as Cass Sunstein calls it, regulation through transparency.

Too big to face incentives

Here, in one sentence, is what's wrong with Stewart Baker's testimony on cybersecurity before the Senate Homeland Security committee today:

If an asset is not designated as "covered critical infrastructure," then the owner has no obligation under the bill to guard against attack by hackers, criminals, or nation states, leaving those who depend on the asset unprotected.

The logic here is that if a private network is not forced by government to protect itself, then it will be left unprotected and wide open for attack. There is no private incentive to secure one's investment, the argument seems to be. If you'd like an explanation of why this isn't logical, see Eli Dourado's paper on cybersecurity market failure.

One more thing: according to Baker, present network insecurity "could easily cause the United States to lose its next serious military confrontation." I understand asymmetric threats, but here is a listing of military spending by country. "Easily" doesn't come to mind.

February 15, 2012

It might be good to try a little harder on copyright

Kevin Drum and Tim Lee have been having an interesting exchange about whether those of us who oppose granting copyright holders stronger enforcement powers feel this way because we are ideologically opposed to IP protection. Tim points out that copyright owners have, as a matter of fact, received greater and greater enforcement powers–almost on an annual basis. As a result, Tim says, "most of us are not anti-copyright; we just think enough is enough, and that the menu of enforcement tools Congress has already given to copyright holders is more than sufficient."

Sufficient for what, though? Sufficient to significantly reduce piracy online? That's certainly not the case. Piracy is rampant on the net. Some would say, though, that the only meaningful ways left to enforce copyright would (dare I say it?) break the Internet as we know it.

So I think that when Tim says that the powers copyright holders now have are "more than sufficient," I think he means sufficient to provide an incentive to create. After all, the purpose of copyright is to "promote the progress of science," not to protect some Lockean notion of property. It may be the case that while owners' rights are no doubt being violated, a further reduction in piracy won't affect the incentive to create.

This is why many, including Julian Sanchez, Tim O'Reilly, Mike Masnick and Jonathan Coulton, question whether piracy is really a problem at all. That is, they don't believe it may be the case that the present level of piracy doesn't hurt content owners' bottom lines because it's clear that not every infringement would have otherwise been a sale. If that's the case, then the costs of new enforcement powers would outweigh any benefits. So, the argument goes, we should do nothing.

Another argument might be that even if there is some harm on the margin to content owners from piracy–some reduction in the incentive to create–the toll a bill like SOPA would take on free speech and innovation are just not worth the reduction in piracy. So, again, we should do nothing.

Two observations about this. First, many folks, including many policymakers, do in fact take a Lockean view of copyright. I think this is why many persons believe that opponents of new legislation are secretly IP anarchists. We need to do a better job of explaining the utilitarian purpose of Copyright. (I like to tell my friends on the Right that I'm for the "originalist vision of copyright" that the Founding Fathers intended.)

Second, it's practically impossible to figure out the exact effect of online piracy on the economy, let alone creators' incentives. In my view the truth is much closer to the "there's no problem" end of the spectrum than to the inflated estimates put forth by the content industry. But, it's certainly possible that there is too much piracy. If that's the case, and we do believe in copyright, then I think it's incumbent upon us to try to develop alternatives to reduce piracy without breaking the Internet. I'm not saying we should advocate for these, just that we should think about what those are.

If nothing else, we'll be able to point to these alternatives when the next SOPA is portrayed as the only possible solution. Otherwise, people like RIAA President Cary Sherman will get away with saying that we have no "constructive alternatives" or that we're IP anarchists.

Kevin Drum thinks that we may yet see a technical solution emerge that reduces piracy while preserving an open Internet. That may be, but color me skeptical. I think it will have to be a legislative solution. What that should be, I don't know. The OPEN Act is one alternative. Compulsory licensing, however unpopular, is another way to tackle the issue. I'm sure there are others.

It's a hard problem, and there are no easy answers. But if we do believe in copyright, then I think the intellectually honest thing to do is to spend some time thinking about how to reduce piracy, on the margin, without breaking the Internet. We can do this at the same time we fight for greater recognition of fair use, to protect the public domain, and to roll back terms and other over-reaching in copyright.

Let's Craft the Perfect Internet Policy… No, Wait, It's Already Been Done!

Friends of Internet freedom, I need your assistance. I think we need to develop a principled, pro-liberty blueprint for Internet policy going forward. Can you help me draw up five solid principles to guide that effort?

No, wait, don't worry about it… it has has already been done!

As I noted in my latest weekly Forbes column, "Fifteen years ago, the Clinton Administration proposed a paradigm for how cyberspace should be governed that remains the most succinct articulation of a pro-liberty, market-oriented vision for cyberspace ever penned. It recommended that we rely on civil society, contractual negotiations, voluntary agreements, and ongoing marketplace experiments to solve information age problems. In essence, they were recommending a high-tech Hippocratic oath: First, do no harm (to the Internet)."

That was the vision articulated by President Clinton's chief policy counsel Ira Magaziner, who was in charge of crafting the administration's Framework for Global Electronic Commerce in July 1997. I was blown away by the document then and continue to genuflect before it today. Let's recall the five principles at the heart of this beautiful Framework:

1. The private sector should lead. The Internet should develop as a market driven arena not a regulated industry. Even where collective action is necessary, governments should encourage industry self-regulation and private sector leadership where possible.

2. Governments should avoid undue restrictions on electronic commerce

. In general, parties should be able to enter into legitimate agreements to buy and sell products and services across the Internet with minimal government involvement or intervention. Governments should refrain from imposing new and unnecessary regulations, bureaucratic procedures or new taxes and tariffs on commercial activities that take place via the Internet.3. Where governmental involvement is needed, its aim should be to support and enforce a predictable, minimalist, consistent and simple legal environment for commerce

. Where government intervention is necessary, its role should be to ensure competition, protect intellectual property and privacy, prevent fraud, foster transparency, and facilitate dispute resolution, not to regulate.4. Governments should recognize the unique qualities of the Internet

. The genius and explosive success of the Internet can be attributed in part to its decentralized nature and to its tradition of bottom-up governance. Accordingly, the regulatory frameworks established over the past 60 years for telecommunication, radio and television may not fit the Internet. Existing laws and regulations that may hinder electronic commerce should be reviewed and revised or eliminated to reflect the needs of the new electronic age.5. Electronic commerce on the Internet should be facilitated on a global basis

. The Internet is a global marketplace. The legal framework supporting commercial transactions should be consistent and predictable regardless of the jurisdiction in which a particular buyer and seller reside.

It doesn't get much better than that. Sure, some will nitpick about some of the Clinton Administration's views on a few issues like encryption and copyright, but the fact remains that we would be hard-pressed today to come with a better set of general principles to guide Internet policymaking than those five. And these principles can be embraced in a non-partisan fashion. Liberal and conservatives alike should learn to abandon their pet regulatory issues and instead embrace this more principled approach to keeping government's paws off the Net before cyberspace gets smothered by red tape both here and abroad.

Finally, I encourage you to also check out this remarkable speech that Ira Magaziner delivered two years after issuing the Framework in which he argued that "even if it were desirable to centrally control the Internet in some way, it is impossible, and life is too short to spend too much time doing things that are impossible. By the same token, we need to respect the nature of the medium in the sense that technology moves very quickly, and any policy that is tied to a given technology is going to be outmoded before it is enacted."

He concluded that speech by noting that we should rely "first and foremost on the marketplace and on self-regulation, of limited and highly targeted government involvement based on consensus, of non-partisan debate and international cooperation. Most importantly of all," he said, we should "retain a sense of humility and…acknowledge that none of us can, on these issues at least, claim to have all the answers."

Yes, yes, YES! Such humility is sorely lacking in our policymakers today.

So, who will join me in renewing the fight for the Clinton-Magaziner vision for the Internet policy?

February 14, 2012

We're not kidding about overheated cybersecurity rhetoric

Tate Watkins and I have an essay in Wired today looking at how the overheated rhetoric and unsupported claims around cybersecurity inflate the threat and may lead us to a new cyber-industrial complex. It's the same theme we explore in our recent Harvard National Security Journal article and also in a feature in Reason a few months ago.

Rockefeller on #Cybersecurity : planes slamming into one another, chemical plant explosions "on the brink of what could be a calamity"

— Katy Bachman (@KatyontheHill) February 14, 2012

What do we mean by overheated rhetoric that serves more to scare than to inform? Here are some statements from Sen. Jay Rockefeller introducing the comprehensive cybersecurity bill on the Senate floor today:

"The experts are warning us that we are on the brink of something much worse. Something that could bring down our economy, rip open our national security, or even take lives. The prospect of mass casualty is what has propelled us to make cybersecurity a top priority for this year, to make it an issue that transcends political parties or ideology. …

"Admiral Mike Mullen, former Joint Chiefs chairman, said that a cybersecurity threat is the only other threat that is on the same level as Russia's stockpile of nuclear weapons. …

"We are on the brink of what could be a calamity. A widespread cyber attack could potentially be as devastating to this country as the terror attacks that tore apart this country 10 years ago. …

"Think about how many people could die if a cyber-terrorist attacked our air traffic control system, both now and when it's made modern, and our planes slammed into one another. Or rails switching networks were hacked causing trains carrying people, and more than that perhaps hazzardous material, toxic materials, to derail or collide in the midst of our most populate urban areas like Chicago, New York, San Francisco, Washington, DC, etc."

He also touch on pipeline explosions and electricity blackouts, of course, and said that we needed to act immediately. It seems that some GOP senators are calling for a delay on the bill. Stay tuned.

Jonathan Coulton on music piracy

On the podcast this week, Jonathan Coulton, a musician, singer-songwriter, and geek icon, who releases his music under a Non-Commercial Creative Commons License, discusses his thoughts on piracy from an artist's point of view. Coulton talks about quitting his day job so he could focus on his music. He bypassed the traditional route of becoming a musician, which usually means signing to a record label, and began releasing one song per week on his website. This lead to eventual success, according to Coulton, who now makes his living as a full-time musician by touring and selling his music on his website. The discussion then turns to piracy. Coulton explains why he thinks piracy cannot be stopped and describes what he considers "victimless piracy." He goes on to discuss the difficulties of addressing piracy issues, especially when taking fairness and practicality into account.

Related Links

"MegaUpload", on Coulton's blog"Internet to Artists: Drop Dead", Wall Street JournalThing a Week, on jonathancoulton.com

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the webpage for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower