Beth Kephart's Blog, page 77

August 4, 2014

Five Days at Memorial/Sheri Fink: Reflections

In 2004, as the chair of the Pen First Nonfiction Award, I met Sheri Fink at Lincoln Center. Her book, War Hospital, about physicians working under siege during the Bosnian crisis, was an award finalist. She was in the house, as they say. Gracious. Gentle. Unpretentious.

In 2004, as the chair of the Pen First Nonfiction Award, I met Sheri Fink at Lincoln Center. Her book, War Hospital, about physicians working under siege during the Bosnian crisis, was an award finalist. She was in the house, as they say. Gracious. Gentle. Unpretentious.Fink has a degree in psychology from the University of Michigan and a PhD in Neuroscience and an MD from Stanford University. She is an elegantly boned woman who has assisted refugees on the Kosovo-Macedonia border, in Haiti, Iraq, Mozambique, and elsewhere. Over the course of six years, she researched and reported on the devastating choices made at Memorial Hospital in New Orleans, in the wake of Katrina. That book—Five Days at Memorial: Live and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital—quickly became a national bestseller and an award winner when it was released last year.

I had previously read passages. I am, at last, reading the whole.

Why do we need long-form narrative nonfiction? Why are writers like Sheri Fink as important as politicians—and more powerful than almost any elected official in the stagnated United States right now? Because we are a people, too often, who form opinions based on a headline, a two-minute news segment, a tweet. Because we cannot, on our own, develop a rounded understanding of all the underlying causes of disaster. Because narrative nonfiction of the caliber of a Sheri Fink book forces us to slow down. It illuminates the extenuating circumstances. It yields the stage to a company instead of a solitary actor. It unpacks time. It shows us what it was really like, say, in the aftermath of a storm as generators died, ventilators failed, a hospital became a cauldron, communications were lost, bathrooms overflowed, pets squealed, thugs threatened, helicopters got waved away, pilots grew impatient, and nobody could find any What To Do In Case Of This instructions, because there weren't any. The doctors, nurses, patients, and family members were essentially on their own.

And bad things happened. Terrible things, wrong decisions, accusations of euthanized patients, arrests.

It is shocking. It is shattering. It is a true story—some 500 interviews true. Sheri Fink gave six years of her life to reporting on Memorial so that this sort of thing would not happen again. So that a national conversation might be had, so that guidelines might be put into place, so that a tragedy of this scale might be better imagined and better prevented.

The storms are upon us.

Such dire choices are not just a thing of the past, a relic of our curious history.

Sheri writes about important things with deep, abiding knowledge. Somehow, at the same time, she writes with glorious skill, great fluency, beauty.

The situation was inhuman. Humans were left to figure it out. Here is a brief sampling of Sheri's prose—the world beyond the hospital doors.

A radio played in the corridor, transmitting tales that alarmed the LifeCare staff: hostage situations, prison breaks, someone shooting at police. Looters had used AK-47 assault rifles to commandeer postal vehicles, filling them with stolen good, according to a councilman from Jefferson Parish, which shared a border with the city. A deputy sheriff said on air that he saw a shark swimming around a hotel—or perhaps it was just debris that looked like a shark fin; he wasn't sure.

Published on August 04, 2014 04:51

August 3, 2014

Sekret/Lindsay Smith: Reflections

In June, at Books of Wonder, I met (among other fine writers) the debut novelist Lindsay Smith, who professed a love for Russian culture. She has traveled to Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Siberia. She writes about foreign affairs in Washington, DC. And for her first novel she imagined a 17 year old named Yulia who has psychic capabilities and is "recruited" (to use a kind word) by the KGB.

In June, at Books of Wonder, I met (among other fine writers) the debut novelist Lindsay Smith, who professed a love for Russian culture. She has traveled to Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Siberia. She writes about foreign affairs in Washington, DC. And for her first novel she imagined a 17 year old named Yulia who has psychic capabilities and is "recruited" (to use a kind word) by the KGB.Lindsay's sentences have pace and glimmer. Her knowledge of that time is stunning. And when I reached this passage, about East Berlin, I knew I was in the company of a like-minded researcher and writer. How beautifully she captures that place. It's a slightly different (by which I mean earlier) Berlin from the one I write of Going Over. But it is wholly recognizable to those who have read the history books.

East Berlin is a concrete crypt. Everywhere I look, stark, flat buildings rise out of shell-shocked rubble and watch us with broken windows for eyes. The streets hold no cars. The old buildings—from before Stalin seized this land for his own—look safe from one side, but when we pass them, the rest is crumpled by artillery fire, the wreckage blocked off by barbed-wire fences. The few people we pass fix their stares on their feet and hurry past us. Coal smoke and sulfur linger around every corner as we wade through half-melted black slush.Congratulations to a young writer with great seriousness of purpose—and reliable knowledge.

Published on August 03, 2014 10:06

Behind the Beautiful Forevers/Katherine Boo: Reflections

With Behind the Beautiful Forevers, Pulitzer Prize winner Katherine Boo does more than merely bear witness in Annawadi, the slum that grew up in the shadows of the Mumbai airport and features a sewage lake, horses painted to mimic zebras, and every possible form of corruption.

With Behind the Beautiful Forevers, Pulitzer Prize winner Katherine Boo does more than merely bear witness in Annawadi, the slum that grew up in the shadows of the Mumbai airport and features a sewage lake, horses painted to mimic zebras, and every possible form of corruption.She does more than sit with the trash pickers, the schemers, the envious, the hungry, the souls who conclude that death is the only way out.

She tells a story. She involves her readers in the intimate dramas of an open-wound place. She compels us to turn the pages to find out what will happen to the prostituting wife with half a leg, the boy who is quick to calculate the value of bottle caps, the man with the bad heart valve, the "best" girl who hopes to sell insurance some day, the "respectable" rising politician who sleeps with whomever will help her further rise, the police who invent new ways to crush crushed souls.

She engages us, and because she does, she leaves us with a story we won't forget. Like Elizabeth Kolbert, another extraordinary New Yorker writer, Boo takes her time to discover for us the unvarnished facts, the pressing needs, the realities of things we might not want to think about.

But even if we don't think about them, they are brutally real. They are.

A passage:

Like the photos featured in this earlier blog post, the picture above is not Mumbai; I've never been to India. It is Juarez, another dry and needing place on this earth.

What was unfolding in Mumbai was unfolding elsewhere, too. In the age of global market capitalism, hopes and grievances were narrowly conceived, which blunted a sense of common predicament. Poor people didn't unite; they competed ferociously amongst themselves for gains as slender as they were provisional. And this undercity strife created only the faintest ripple in the fabric of the society at large. The gates of the rich, occasionally rattled, remained unbreached. The politicians held forth on the middle class. The poor took down one another, and the world's great, unequal cities soldiered on in relative peace.

Published on August 03, 2014 07:44

Juarez. Mumbai. The children with whom we fall in love.

Last week, over dinner, I was telling friends about Juarez—about the trip we took years ago to a squatters' village, where we met some of the most gorgeous young people I'll ever know. We'd gone to help build a bathroom in a community without water. The children emerged from homes like those above, impeccably dressed and mannered.

Last week, over dinner, I was telling friends about Juarez—about the trip we took years ago to a squatters' village, where we met some of the most gorgeous young people I'll ever know. We'd gone to help build a bathroom in a community without water. The children emerged from homes like those above, impeccably dressed and mannered.Yesterday and today I am reading, at last, Katherine Boo's Behind the Beautiful Forevers. I bought the book the week it came out. It has sat here ever since, waiting for me to find time. I am, as most people know, a devotee of well-made and purposeful documentaries. Reading Boo is like watching one of those. Her compassion, her open ear, her reporting—I'll write more of this tomorrow. But for this Sunday morning I want to share again the faces of the children I fell in love with, the children who eventually worked their way into my young adult novel, The Heart Is Not a Size.

They are breathtaking. Still. And I, as a writer, remain most alive when I feel that the story I tell might make a difference.

Published on August 03, 2014 05:08

August 2, 2014

The Yellow Birds/Kevin Powers: Reflections

It's a rare thing when a book of exquisite literary merit is also a national bestseller. Anthony Doerr's All the Light We Cannot See is one current example. So is Kevin Powers' The Yellow Birds.

It's a rare thing when a book of exquisite literary merit is also a national bestseller. Anthony Doerr's All the Light We Cannot See is one current example. So is Kevin Powers' The Yellow Birds.I should have read Powers' astonishing book sooner—when it was nominated for the National Book Award, when it was named my own city's One Book, when the reviewers clearly couldn't find words, when my neighbor Jane quoted from an early page, when Serena said I should. But I am glad that I read this book on this week, when the wars of the world have sent a deep laceration through my heart, when the news (so terrible) has required me, at times, to look away. By the force of his language, by the intelligence of his structure, by the hallowing, intimate truths on every page, Powers does not allow us to look away. This war that he writes of, his Iraq, his losses, his guilt—this may be a novel, but those losses are real.

If nothing else you have ever read calculates, for you, the cost of war, this book will.

There are spare moments of beauty, too. And because we are all feeling whacked by the news, I share the most stunning here. Two soldiers, the key characters in this book, have been covertly watching a female medic. Our narrator tells us this:

And I thought it was this and not her beauty that brought Murph there over those long indistinguishable days. That place, those little tents at the top of the hill, the small area where she was; it might have been the last habitat for gentleness and kindness that we'd ever know. So it made sense to watch her softly sobbing in the open space of a dusty piece of ground. And I understood why he came and why I couldn't go, not just then at least, because one never knows if what one sees will disappear forever. So sure, Murph wanted to see something kind, he wanted to look at a beautiful girl, he wanted to find a place where compassion still happened, but that wasn't really it. He wanted to choose. He wanted to want. He wanted to replace the dullness growing inside him with anything else.

Published on August 02, 2014 04:26

August 1, 2014

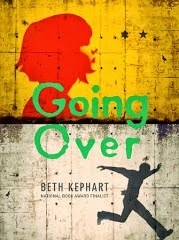

GOING OVER: On the Goodreads 100 Children's Books to Read in a Lifetime

It feels awkward to ask for your help, but today I do.

It feels awkward to ask for your help, but today I do.Going Over (my agent, Amy Rennert, learned) is currently listed as a Goodreads 100 Children's Books to Read in a Lifetime, along with the Harry Potters, Goodnight Moon, and so many great classics.

The list is active, updated through voting. You can do that, easily, here.

Your vote would mean the world.

(Added on a sheepish Saturday morning. I realized, moments ago, that this is the Goodreads list, modeling the Amazon list. My apologies for the earlier error! Excitement laid its odd hands on me.)

Published on August 01, 2014 10:45

Me and Louisa May Alcott at the Philadelphia International Airport

A little over a year ago I had the tremendous honor of being included in the Philadelphia Literary Legacy at the Philadelphia International Airport, a year-long exhibition featuring 50 writers who had passed through or grown up in my region since the Constitutional Convention.

A little over a year ago I had the tremendous honor of being included in the Philadelphia Literary Legacy at the Philadelphia International Airport, a year-long exhibition featuring 50 writers who had passed through or grown up in my region since the Constitutional Convention.A highlight of my life. (For images from that day, go here.)

Not long ago, that exhibit was replaced with a fantastic portfolio of images about Philadelphia and its history of civil rights.

I had no idea, until moments ago, that portions of the Literary exhibition are still in tact at the airport. I know this because my good friend K.M. Walton took the time to snap this photo and to share it with me.

Thank you, Kate.

Published on August 01, 2014 06:20

July 31, 2014

Kevin Powers on faith in finely tuned language

A few days ago I wrote of my urgent need, this summer, for urgent books. I'm inside of one of those right now—Kevin Powers' war novel, The Yellow Birds, which earns both its literary accolades and its bestseller status. In an interview with Jonathan Ruppin included in the paperback edition, Powers says this about language:

A few days ago I wrote of my urgent need, this summer, for urgent books. I'm inside of one of those right now—Kevin Powers' war novel, The Yellow Birds, which earns both its literary accolades and its bestseller status. In an interview with Jonathan Ruppin included in the paperback edition, Powers says this about language:You're also a poet and this comes across in the deeply lyrical quality of your prose. Was this intended in counterpoint to the rawness of the dialogue?

I intended it as a counterpoint not just to the rawness of the dialogue, but also to the rawness of the experience. In that respect it is more point than counterpoint. In trying to demonstrate Bartle's mental state, I felt very strongly that the language would have to be prominent. Language is, in its essence, a set of noises and signs that represent what is happening inside our heads. If I have faith that those noises and signs can be received and understood by another person, then I should also have faith that they can be made more finely tuned.

Published on July 31, 2014 07:35

I'm adopting the artist Meera Lee Patel

I'll tell you all the reasons soon.

I'll tell you all the reasons soon.For now: Is she gorgeous, or what?

Read a Free People interview here.

Enjoy her art here.

Celebrate her spirit.

Published on July 31, 2014 04:19

July 30, 2014

Nesting: an early poem from years ago

Late last night, a beloved former neighbor, digging around in her attic, finds a poem I'd written for her daughter years ago and take the time to type it for me.

Late last night, a beloved former neighbor, digging around in her attic, finds a poem I'd written for her daughter years ago and take the time to type it for me."Nesting," I'd called it. This long-time obsession with birds.

Nesting

(For Hae Linn)

In high summer

A Christmas cactus

Awkwardly hung

And nested

With finch.

I believe you were seven

When they

Broke into life,

And blind-eyed,

Panicked for the light.

At dusk,

When the air cooled,

We would pull their roosting down

To find the fur and murmurs

Redefined.

Though still too young,

They yearned to fly

And in the last

They, in a tremble,

Bent wings between the sky.

We spent the night

In search of

Cactus-sown finch:

You certain they would survive;

I, silently, not...

Though, perhaps, in another form,

They did,

If once more redefined

And mindless

Or the fragments left behind.

Today is the last day that Nest. Flight. Sky.: On Love and Loss One Wing at a Time, my Shebooks memoir, can be downloaded for free, the details here.

(It goes without saying that that is no finch in the photo, but a miniature owl I encountered in southeast Alaska.)

Published on July 30, 2014 03:17