Beth Kephart's Blog, page 44

July 10, 2015

The Thing About Jellyfish/Ali Benjamin: a major new voice for younger readers (for all readers)

When Jessica Shoffel speaks, I listen.

When Jessica Shoffel speaks, I listen. She's the sort of person who makes you feel seen. The sort who, as a Penguin publicist, didn't just oversee the campaigns of mega-watt writers like Laurie Halse Anderson and Jacquelyn Woodson, but also took time to read my novel Small Damages, to tell me how the story worked within her, and to create a glorious press release and campaign on its behalf. The sort who stood with me through a difficult time. The sort who found me alone at the Decatur, GA, book festival and included me in conversations, in a dinner, in a memorable hour with Tomie dePaulo. The sort who makes time in a hugely busy life to reach out to young people who have experienced loss, to run marathon races on behalf of medical research, and to talk to a dear family member, Kelsey, about what it is like to work among books. Jess is smart and gracious and kind and hard working. She is there. She is present. She is with you; she is for you. She is a rare kind of sisterhood.

And so when Jess wrote a few weeks ago to tell me about a book she had just read in her new role as Director of Publicity for Little Brown and Company's Books for Young Readers, when she said it was my kind of book, I didn't for one instant doubt her. Can I send it to you? she asked. Of course, I said.

And so it arrived. And so I have read it.

This book—this gorgeous, intelligent, moving, seamless, award-destined, Andrea Spooner edited book—is a debut middle grade novel by Ali Benjamin called The Thing About Jellyfish. Everything about this story enwraps, engages, enraptures. Its frizzy-haired, science-leaning, universe-scanning narrator who has lost her former best friend. Its obsession with the jellies that bloom incessantly within our seas, leave the big whales hungry, endanger us with their undying stings. Its child-hearted hopes and its big-minded mix of science and mystery. Its neat division into paper parts—purpose, hypothesis, straight through to conclusion. Its language—just the right bright, the right curious. (I could quote from every single line and prove that to you; Ali Benjamin never writes anything less than a wonderful sentence.) The science itself—impeccably (never intrusively) filtered into this story about friendship, family, school, and school teachers who care.

And then—watch—Diana Nyad appears. Diana Nyad, the endurance swimmer who refused to give up on her dream. The endurance swimmer who braved the countless jellyfish stings and made it to the other side. Symbol, hero, character. There she is, in this most exquisite book.

(For more on Diana and her relationship with my friend and agent Amy Rennert, read here. And look for Diana's much buzzed memoir, Find a Way, out in October).

In this summer of contemplation, this summer of weighing the odds, of wondering through the writing again, of maybe or maybe not trying again, of not knowing, it is a glorious thing to be reminded of what is possible with books. The thing about The Thing About is what says about what possible is.

Published on July 10, 2015 05:01

July 8, 2015

Because people don't see you or see what you're doing doesn't mean you don't exist (Patti Smith)

I am in the midst of a most emotional summer, and I'm just letting that be. Not building walls around my feelings. Not afraid to sit and reel.

I am in the midst of a most emotional summer, and I'm just letting that be. Not building walls around my feelings. Not afraid to sit and reel.This afternoon I've been reading Patti Smith's new memoir, M Train, due out in a few months. I will tell you right now that this book is fierce beauty if ever there was fierce beauty. This book is cloud sweep, glistened web, vast and aching, a room in which to cry. I can't say more than that for awhile now. Just. Oh, my goodness. This book.

I stopped in the midst of my reading to return to an interview Smith did with Rolling Stone magazine in 1996, a few short years after Smith's beloved husband, Fred, passed away from heart failure. The interviewer has been speaking of how Smith "literally disappeared during the 1980s." Smith has talked about the greatness of that period, how the couple traveled America, lived in cheap hotels, loved. He would study flying. She would write poems and stories the world wouldn't see for years.

Now the interviewer asks Smith about the transition from that period of rock and roll stardom to "almost complete anonymity." Smith's response, in part:

Because people don't see you or see what you're doing doesn't mean you don't exist. When Robert [Mapplethorpe] and I spent the end of the '60s in Brooklyn [NY] working on our art and poetry, no one knew who we were. Nobody knew our names. But we worked like demons. And no one really cared about Fred and I during the '80s. But our self-concept had to come from the work we were doing, from our communication, not from outside sources.

Necessary words for those of us who are still waiting for that big (or small) break, for those of us whose time seems to have come and gone, for those of us deliberately stepping off the trammeled path to think for a bit, to reconceive.

Necessary words.

Published on July 08, 2015 17:07

July 7, 2015

Violent. Fierce. Proud.: Reviewing Lidia Yuknavitch's THE SMALL BACKS OF CHILDREN

Lidia Yuknavitch is fearless—a trait I typically admire. Her new book opens with an exquisite scene and then slowly peels away to fractions. My reflections on it all are here, in the

New York Journal of Books.

Lidia Yuknavitch is fearless—a trait I typically admire. Her new book opens with an exquisite scene and then slowly peels away to fractions. My reflections on it all are here, in the

New York Journal of Books.

Published on July 07, 2015 12:48

let wonder be our guide in this age of the apocalpytic: Leif Enger/Peace Like a River

I confess: I am the last person in America to read Leif Enger's Peace Like a River. The last person to wake earlier than the usual early to get more pages in. The last person to brim up over the magnitude of this book's heart. The last person to sit very quietly still after the final sentence was sung and wish that the book had not been read yet—that it was still out there, rewarding discovery, still out there, beckoning.

I confess: I am the last person in America to read Leif Enger's Peace Like a River. The last person to wake earlier than the usual early to get more pages in. The last person to brim up over the magnitude of this book's heart. The last person to sit very quietly still after the final sentence was sung and wish that the book had not been read yet—that it was still out there, rewarding discovery, still out there, beckoning.For what a book is this book about an asthmatic boy and his literary sister, their miracle-stirring father, their outlaw brother, the minor and major sacrifices one makes when protecting love against the provable facts of a crime. This story about the wild west, the Valdezes and Cassidys, the crags in the earth that burn unending fires, the storms that blow in the snow or simply blow the snow, the quality of icing on cinnamon raisin buns. The stars:

They burned yellow and white, and some of them changed to blue or a cold green or orange—Swede should've been there, she'd have had words. She'd have known that orange to be volcanic or forgestruck or a pinprick between our blackened world and one the color of sunsets. I thought of God making it all, picking up handfuls of whatever material, iron and other stuff, rolling it in. His fingers like nubby wheat. The picture I had was of God taking these rough pellets by the handful and casting them gently, like a man planting. Look at the Milky Way. It has that pattern, doesn't it, of having been cast there by the back-and-forward sweep of His arm?

Magnificent, right? Magnificent. And not an ounce of the angry in this book, which is not to say there is no moral complexity or confusion. Not a whiff of cynicism, which is not to say that this ageless/timeless book is devoid of brave impartings. When I think about why I love this book so much, I think it has something to do with this: it is not afraid to be alive with the wonder of our living.

Am I right? Perhaps. For when I set off to read more about Enger, I came upon this excerpt from a Mark LaFramboise interview. Wonder is his topic—the importance of holding fast, and holding true, to the mysterious.

There is no greater lesson, I believe, for anyone writing right now. We seem in all-out pursuit of edge and bitterness, declarations of the apocalyptic. But aren't our very best books sprung from respect for natural and man-made loveliness?

Q: Although the narrator tells the story in retrospect, we see the world through the eleven- year old eyes of Reuben. How were you able to capture the wonder, fears, and curiosity of such a young protagonist?

A: First, my parents gave me the sort of childhood now rarely encountered. Summers were beautiful unorganized eternities where we wandered in the timber unencumbered by scoutmasters. We dressed in breechclouts and carried willow branch bows, and after supper Dad hit us fly balls. It was probably most idyllic for me as the youngest of four, since three worthy imaginations were out beating the ground in front of me; who knew what might jump up? Now I see that same freedom in the lives of our two sons, whose interests cover the known map. It's easy to witness the world through the eyes of a boy when you have two observant ones with you at all times. But the ruinous thing about growing up is that we stop creating mysteries where none exist, and worse, we usually try to deconstruct and deny the genuine mysteries that remain. We argue against God, against true romance, against loyalty and self-sacrifice. What allows Reuben to keep his youthful perspective is that he's seen all these things in action -- he is the beneficiary of his father's faith. He is a witness of wonders. To forget them would be to deny they happened, and denying the truth is the beginning of death.

Published on July 07, 2015 05:47

July 5, 2015

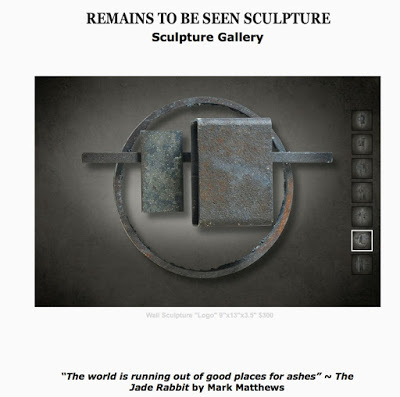

Mary Lee Adler: a sculptor, a friend (Remains to Be Seen)

I met Mary Lee Adler in Miami. She was (in her smart, loving, embracing way) overseeing the young writers of the National YoungArts program. Making sure they were heard. Making sure they were seen. Making sure they were experiencing all that week-long program had to give them.

I met Mary Lee Adler in Miami. She was (in her smart, loving, embracing way) overseeing the young writers of the National YoungArts program. Making sure they were heard. Making sure they were seen. Making sure they were experiencing all that week-long program had to give them.But here's the thing: If those YoungArts writers did nothing more than meet Mary Lee, their week in the Miami sun would have been worth it. I've rarely enjoyed conversation as much as I enjoyed my conversation with this reader/maker/doer. I've rarely felt so privileged.

A Vanderbilt graduate with an English degree, a woman who has traveled the world, a woman who doesn't give up on love or its possibilities, Mary Lee is also a sculptor—a maker of exquisite urns, among other things.

Today I'm celebrating Mary Lee and her artful renditions of the everlasting. Please visit her web site to learn more.

Published on July 05, 2015 06:36

"Don't you be a show-off," and other lessons from Kent Haruf, in his final quiet novel

We lost the great Kent Haruf way too soon. I was privileged to review his final book for the Chicago Tribune—privileged to have the excuse to go back and read Haruf interviews and profiles in preparation for the assignment.

We lost the great Kent Haruf way too soon. I was privileged to review his final book for the Chicago Tribune—privileged to have the excuse to go back and read Haruf interviews and profiles in preparation for the assignment.Oh, he had so much to say. I wish he were still here, saying.

My full review can be found here.

Published on July 05, 2015 04:26

July 4, 2015

reuniting with the sisters of Alaska, on Independence Day weekend

One year ago today I was on a small boat in Alaskan waters and the sky was our fireworks. Tomorrow, my husband, father, and I will have the great pleasure of reuniting with the two sisters we met on this trip—women who exemplify so much that is important, women who, even a year on, carry the traditions of friendship forward.

One year ago today I was on a small boat in Alaskan waters and the sky was our fireworks. Tomorrow, my husband, father, and I will have the great pleasure of reuniting with the two sisters we met on this trip—women who exemplify so much that is important, women who, even a year on, carry the traditions of friendship forward.To our country tonight. To the safety of all those we love, and strangers, too. And to the friendships that sustain us, on Independence Day.

Published on July 04, 2015 16:32

envy shouldn't fuel our conversations, good luck doesn't earn us pride: let us do some good in this world

Being an old woman now, being a veteran of hope and disappointments, promises made and not always kept, I've seen things. I've felt things. I've wondered.

Being an old woman now, being a veteran of hope and disappointments, promises made and not always kept, I've seen things. I've felt things. I've wondered.Many conclusions I've kept to myself. Some I've shared privately, quietly, with friends. Never in a bookstore gathering, nor on a panel, nor in a public forum, nor in a passive-aggressive social-media way have I thought it okay—from a human perspective, from the perspective of career advancement, even—to strike back or out at others. To put one writer or book down in order to promote another. To laugh at the person not in the room, or at the person sitting just a few stools down.

These are books we are writing, and if we are writing them for the right reasons, we're not writing them to win, we're not writing them to be famous, we're not writing them to put ourselves on an endless tour away from home and family. We're not writing so that we will own the headlines. We're writing because within the deep of us, something stirs—idea, character, language. The stuff of the soul.

Good luck in our own careers doesn't earn us entree to prideful pronouncements. Bad luck shouldn't put us on a battleground. Envy shouldn't fuel our conversations.

Our country trembles. Our planet stands at desperate risk. Dangers lurk and hearts are broken. People are dying too soon and for no other reason than that they were in a church at a wrong time, or on a beach when terror came, or in a museum when someone raised a gun, or in a hotel when a plane fell.

May we write books that explore, expose, ponder, transcend, heal. May we live, as authors, with the ambition of doing some measurable good in this world.

Published on July 04, 2015 06:34

July 2, 2015

let young writers write their souls for their souls, and not for all those prizes

In my fourth book, Seeing Past Z: Nurturing the Imagination in a Fast-Forward World, I wondered out loud about what might happen if we stopped competing with and through our children. If we gave them time to become themselves, to work together to build ideas and worlds that are never judged, prized, awarded.

In my fourth book, Seeing Past Z: Nurturing the Imagination in a Fast-Forward World, I wondered out loud about what might happen if we stopped competing with and through our children. If we gave them time to become themselves, to work together to build ideas and worlds that are never judged, prized, awarded.Seeing Past Z was based on the many years I spent teaching children in my home and at a local garden. It was about the beauty of just being together, imagining together, writing together, and not mailing our poems, songs, stories out into the world for "greater" validation. I never re-wrote the children's work, never rewrote the work of my son. What they created they created. They took the pride of ownership. They gained.

From the opening pages of Seeing Past Z:

I want to raise my son to pursue wisdom over winning. I want him to channel his passions and talents and personal politics into rivers of his own choosing. I'd like to take the chance that I feel it is my right to take on contentment over credentials, imagination over conquest, the idiosyncratic point of view over the standard-issue one. I'd like to live in a world where that's okay.

Some call this folly. Some make a point of reminding me of all the most relevant data: That the imagination has lost its standing in classrooms and families nationwide. That storytelling is for those with too much time. That winning early is one bet-hedging path toward winning later on. That there isn't time, as there once was time, for a child's inner life. That a mother who eschews competition for conversation is a mother who places her son at risk for second-class citizenry.

The book was ahead of its time. It sold but a few thousand copies, was remaindered quickly. A few years later the slow parenting movement rolled in. Books about the importance of play and the dangers of the parent-governed resume grabbed headlines. Helicopter parenting was caught in the snare. The family counselors, the social scientists, the psychiatrists sat on the talk-show couches and asked, What have we done to our young?

Yesterday The Atlantic ran an important story by Jen Karetnick titled "Behind the Scenes of Teenage Writing Competitions." The story reminds us of the damage that can get done when teens (and those who oversee their paths to glory) write to win, write to build their resumes. The work is shaped (not always by the teens themselves) to beat the odds. The resumes grow, often at the expense of less-privileged children who don't have writing mentors and editors at their side. And programs designed to help these young people step toward the light are compromised by work that may or may not be the students' own. From the story:

As parents and teachers, as writers and people with more than a few wrinkles by their eyes, let us do what is right by our young people. Let us not rewrite their stories. Let us not allow them to think that winning is more important than knowing. Let us remind them that honesty, authenticity, goodness is the ultimate aim, not stars or unearned privilege. Let them find out who they are.

This destruction of self-esteem and erasing of voice is exactly what Nora Raleigh Baskin, author of the new book Ruby on the Outside, fears. Having taught for almost 15 years at organizations including Gotham Writers Workshop, Raleigh Baskin has seen those mindsets trending. She refuses to critique manuscripts to send off to literary magazines or to judge competitions on the grounds that budding writers’ voices shouldn’t be “held up against a random opinion. This is the time for exploration and for encouragement … Writing is all about process and setting these arbitrary achievements takes away from that.”

For some young writers, that pressure can be far more insidious than the pain of rejection. The competitive spirit may persuade parents to hire well-known writers to tutor, edit, or even rewrite their children’s work. It may even lead minors down the path of plagiarism.

When, for example, I asked my young people to create a character, I gave out no stars. When I served as the Master Writing Teacher at the National YoungArts Foundation a few years ago, I did not go to upgrade the students' work; I went to provoke them with new prompts, new readings, new conversations, to encourage them to dig deeper within their own souls. And at Penn, where I teach a single course once each year, I am not rewriting my students' work, not rewriting their essays. I am pressing them to take each idea and every line farther—for their own sake. I am rewarding hard work and careful thought. I am rewarding personal growth. I am disappointed by those who take short cuts. Because it only hurts them.

One last word on this. Lately I have been going through many boxes from my youth. Reading, with a terrible blush in my cheeks, my early poems. People, they were awful. They were worse than awful. They showed no promise.

But they were mine. Never rewritten, never edited, never smoothed out. It took time time time for me to find my own way, and I'm still struggling. Having never taken formal creative writing classes, having taught myself through the books I've read and the friends I've made, I may still be behind the curve, but I am me behind that curve.

Let the young be themselves. Their breakthroughs will have more meaning.

Published on July 02, 2015 04:45

July 1, 2015

I suddenly had no What Next

People who know me, know: I am one of those. Give me a project, and I get it done. Tell me I have two months, I work toward two weeks. Give me a house to clean or a home to declutter, and I. Am. On. The. Job. I've managed by way of a sort of strictness toward self. Up before the dawn, give myself no excuses, let nobody down. Snip, snip, I'm cracking.

People who know me, know: I am one of those. Give me a project, and I get it done. Tell me I have two months, I work toward two weeks. Give me a house to clean or a home to declutter, and I. Am. On. The. Job. I've managed by way of a sort of strictness toward self. Up before the dawn, give myself no excuses, let nobody down. Snip, snip, I'm cracking.But lately I have lived in the Land of No Routine. A flutter of many things to do. An absence of systems and governing plans. I've been off to New Haven. Then to Krakow. Then to Bethlehem. Then to Arcadia. I've been writing talks, giving talks, reading books, writing reviews, creating classes and teaching classes, hoping for and hoping against, watching the women play soccer, driving quick to see friends, celebrating 30 years of marriage, planning for next New Year's Eve and now (just now) a blueberry festival. I've been helping to advance a family project, seeing my beautiful brother and his family and forgetting to say goodbye to his son (I fixed that!), cleaning out my basement, cleaning out my shelves, cleaning out my drawers, cleaning and cleaning again, writing for clients.

And then, bam, crash, wait. I suddenly had no What Next. For an hour or two late this afternoon, I had nothing that I had to do.

I sat down. I sat still by a screen door, feeling the breeze. I closed my eyes. I listened to a distant hammer bang. I listened to the one bird in the near tree. I listened to my own heart beat. I fell to deepest sleep.

Sometimes sleep is the best job around.

Published on July 01, 2015 15:39