Beth Kephart's Blog, page 258

February 17, 2011

My desk is a mess and my roses are succumbing

but there is sun today, warmth, my friend standing in the parking lot after a lunch we'd shared, pressing her face into the rays. I feel full of possibilities—writing notes into books and on this screen, rippled through with the idea of music and voice, lifted by a text from my son, now taking his second fiction workshop and exhilarated by the critique he's received just an hour ago. "They had so many positive things to say," he texted. But more than that, he has ideas for a revision, and he cannot wait to start.

but there is sun today, warmth, my friend standing in the parking lot after a lunch we'd shared, pressing her face into the rays. I feel full of possibilities—writing notes into books and on this screen, rippled through with the idea of music and voice, lifted by a text from my son, now taking his second fiction workshop and exhilarated by the critique he's received just an hour ago. "They had so many positive things to say," he texted. But more than that, he has ideas for a revision, and he cannot wait to start. You want your children to go their own way, of course you do. But when their lines cross over, into yours, when you share this unspeakable passion for this thing called writing, it's red flowers bursting through a yellow wall, in a city you once walked through, singing.

Published on February 17, 2011 11:27

February 16, 2011

Say Her Name/Francisco Goldman: Reflections

I was in Guanajuato once, three years ago. I walked its streets, silver veined and gold. I slid through its callejones, tilted forward down the hills, hid inside its theater, got lost, for the sake of my camera, did not go to visit the dead, by which I mean, I did not visit the mummies in the mummy museum for I did not wish to imagine that brand of eternal.

I was in Guanajuato once, three years ago. I walked its streets, silver veined and gold. I slid through its callejones, tilted forward down the hills, hid inside its theater, got lost, for the sake of my camera, did not go to visit the dead, by which I mean, I did not visit the mummies in the mummy museum for I did not wish to imagine that brand of eternal.Who can bear it, staring so wide-eyedly at the end?

People who lose people they love are forever staring in, on the end. People who lose people far too soon—a wife, say, a brilliant and beautiful wife on the verge of her own greatness and, perhaps, of motherhood—can only wonder, What if? What if today she were? What if tomorrow she'd still be? What if our child had been born? What if she had finished her story? What if I'd had more of we?

What if?

Hold her tight, if you have her; hold her tight....

Those words above are Francisco Goldman's words. Found toward the end of a book he calls a novel—a story inspired by, required by, the premature death of his young wife, Aura, who wanted to surf a wave but was ruined by a wave, hammered against the floor of the sea. Say Her Name (due out from Grove/Atlantic in April) is 350 pristine pages of reckoning with the impossible. It is the story of a man's irresistible love for his wife, the story of a fractured heart, the waking to the daily blare: Aura is not here.

Goldman calls this a novel, and I respect his choice. It doesn't matter, though, not this time, whatever the book is called, for Say Her Name is a staggering collage of back and forth, the living and the dead, the alive and whole, the just barely breathing. It is heart, all heart, on the page. It is brilliantly structured, a love affair, a tragedy, a work of fine emotional suspense. Last week, in my memoir class, a student asked a question about time, about how to hold the dispersion of many years inside a tight fist, how to locate her themes in a succession of anecdotals. How do you take, in other words (not her words now, but my words), the glimmers and the shadows, the big things and the small things, the imagined, the actual, the not fully known, the never-to-be-reckoned with and make them a coherent, non-linear whole?

The answer to that question lies here, in Say Her Name. [image error]

Published on February 16, 2011 18:56

Sun in New York City

Now, when I travel to New York City, I am looking for the places into which the sun wedges itself, against which the sun leans. The rigging of river boats. The reflections on glass panes. A sudden castle.

Now, when I travel to New York City, I am looking for the places into which the sun wedges itself, against which the sun leans. The rigging of river boats. The reflections on glass panes. A sudden castle.

Published on February 16, 2011 04:50

February 15, 2011

This Kind of Day (English 135-302)

So that (during class) we listened to Yo Yo Ma playing Astor Piazzolla music (fitting, for the CD had been a gift from my fellow faculty member Karen Rile) and Zulu Jive playing "A Sambe Siye e Goli;" we listened and wrote of remembered street-scape scenes; we found our best lines. We thought out loud about the expectations we have of writers we read, the expectations we have of ourselves. We asked: Where do we find music on the page?, and the answers were all at once and different—it's Virginia Woolf, it's Rick Nichols on food, it's Maya Angelou; it's the repeated line, the crescendo line, the long line, the short one; it is what is held and what is sloughed away. There was the crowding in, afterward, the slow goodbyes, and there, in the doorway, stood a student from three semesters ago—still tall, still lean, still so smart; my impromptu escort to the 4:48 train.

So that (during class) we listened to Yo Yo Ma playing Astor Piazzolla music (fitting, for the CD had been a gift from my fellow faculty member Karen Rile) and Zulu Jive playing "A Sambe Siye e Goli;" we listened and wrote of remembered street-scape scenes; we found our best lines. We thought out loud about the expectations we have of writers we read, the expectations we have of ourselves. We asked: Where do we find music on the page?, and the answers were all at once and different—it's Virginia Woolf, it's Rick Nichols on food, it's Maya Angelou; it's the repeated line, the crescendo line, the long line, the short one; it is what is held and what is sloughed away. There was the crowding in, afterward, the slow goodbyes, and there, in the doorway, stood a student from three semesters ago—still tall, still lean, still so smart; my impromptu escort to the 4:48 train.The color of sun.

Published on February 15, 2011 15:46

A dream

Published on February 15, 2011 04:33

February 14, 2011

What did you buy at the Strand?

... I was asked, and of course I never leave a bookstore without something in hand. I found this Errata Editions' reprint, Alexey Brodovitch's Ballet, first published in 1945. According to the provided description, Errata's Books on Books series is "an ongoing publishing project dedicated to making rare and out-of-print books accessible to students and photobook enthusiasts." I could not not support a project such as this, and besides, the book is gorgeous, and besides all that, Brodovitch was a famed designer who had once painted scenes for Diaghilev's Ballet Russes and after that became a textile and jewelry artist, all the while working as a designer of magazines until finally becoming the art director of Harper's Bazaar. He took the photographs that became Ballet behind the scenes, in New York theaters, caring only to capture the movement and mood and disregarding technical theory.

... I was asked, and of course I never leave a bookstore without something in hand. I found this Errata Editions' reprint, Alexey Brodovitch's Ballet, first published in 1945. According to the provided description, Errata's Books on Books series is "an ongoing publishing project dedicated to making rare and out-of-print books accessible to students and photobook enthusiasts." I could not not support a project such as this, and besides, the book is gorgeous, and besides all that, Brodovitch was a famed designer who had once painted scenes for Diaghilev's Ballet Russes and after that became a textile and jewelry artist, all the while working as a designer of magazines until finally becoming the art director of Harper's Bazaar. He took the photographs that became Ballet behind the scenes, in New York theaters, caring only to capture the movement and mood and disregarding technical theory.This is a phenomenal book, a perfect Valentine's Day book, an important series. I'd never seen it anywhere, until I happened on the Strand.

Published on February 14, 2011 13:22

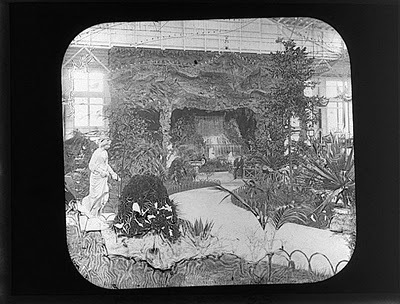

Talking the Centennial, Operti's Tropical Garden, and the Birthing of Fiction in Nonfiction

When St. John's Presbyterian Church invited me to speak for a Valentine's Day luncheon, we all envisioned a group of a dozen or so kind souls, gathered in a circle in the Carriage House. Our dozen has grown to nearly 80, I'm told, and I want to be sure that I deliver. And so, in found pockets of time this past week, I've been returning to my Dangerous Neighbors research files and assembling a 20-image Centennial Philadelphia talk that melds the known with the unknown and in that way reveals my own fiction-making process.

When St. John's Presbyterian Church invited me to speak for a Valentine's Day luncheon, we all envisioned a group of a dozen or so kind souls, gathered in a circle in the Carriage House. Our dozen has grown to nearly 80, I'm told, and I want to be sure that I deliver. And so, in found pockets of time this past week, I've been returning to my Dangerous Neighbors research files and assembling a 20-image Centennial Philadelphia talk that melds the known with the unknown and in that way reveals my own fiction-making process.Those of you who have read Dangerous Neighbors (Egmont USA) know that key moments unfold within and outside of Operti's Tropical Garden, which stood on the margins of the Centennial grounds. Contemporary reporters described Operti's as "one of the handsomest places of amusement in Philadelphia. It was light and airy, and was handsomely decorated with frescoes and other paintings. Long lines of colored globes, each containing a gas jet, stretched across the interior beneath the ceiling, and shed a brilliant light upon the scene below. At the back a large waterfall dashed over the painted rocks, forming a beautiful cascade, and giving to the air on the hot nights of the summer a delicious coolness."

More than sixty performers led by a certain Signor Giuseppe Operti filled the place with music each night—the cascade being dimmed long enough for the music to soar, and then "spr(inging) into life again." Years later, working with those lines of description and this image, I was inspired to imagine a bird set free and all the nuanced consequences. From Dangerous Neighbors:

p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }p.MsoCommentText, li.MsoCommentText, div.MsoCommentText { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }span.MsoCommentReference { }span.CommentTextChar { }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

Operti's is an aromatic cove of high skies and blooms. Gas lanterns float like kites overhead. Potted trees shadow the paths. There are the bright flags of celosia and astilbe,

Published on February 14, 2011 05:15

February 13, 2011

Being Polite to Hitler/Robb Forman Dew: Reflections

It's been a decade or so since Elizabeth Taylor of the Chicago Tribune invited me to review Robb Forman Dew's novel, The Evidence Against Her. I didn't know Robb at the time, but I quickly grew enamored of her gifts, her craftsmanship. I didn't, in fact, expect that I ever would know Robb, nor imagined that she'd find the words I'd ultimately write about her novel. I was wrong, of course. Robb found my words. She wrote me a letter. And soon Robb and I were friends.

It's been a decade or so since Elizabeth Taylor of the Chicago Tribune invited me to review Robb Forman Dew's novel, The Evidence Against Her. I didn't know Robb at the time, but I quickly grew enamored of her gifts, her craftsmanship. I didn't, in fact, expect that I ever would know Robb, nor imagined that she'd find the words I'd ultimately write about her novel. I was wrong, of course. Robb found my words. She wrote me a letter. And soon Robb and I were friends.In the intervening years, Robb sent books, she sent a tapestry she'd found in an old barn, she sent notes, she sent encouragement, she sent praise of a novel on which I worked. She sent us—her large coterie of writerly friends—something we might do in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the name and address of a school to which we all might send boxes of brand new, hand-picked books. Robb proved to be one enormously generous soul, and then things got quiet as she settled into work again, and I waited for what would come next, and next.

I just now finished reading Robb's masterful new novel—its title as clever as the rest of it. Being Polite to Hitler carries forward, from The Evidence Against Her, a certain Agnes Scofield and her close-knit, famous-in-Washburn, Ohio kin. It takes us to October of 1953 on through to the early 1960s on the wings of some of the most gracious writing you'll ever find and some of the most seamless historicism I've ever seen in a novel. No doubt Robb did her homework for this story—sourcing the telling details of Yankees games and Sputnik, home perm kits and development housing, polio and fashion. But more importantly, none of it feels heavy or dug in. It's just life as Agnes Scofield knows it, and what's most important, always, is Agnes and her kin.

I could conceivably quote from every line in this book; I've dogearred the whole, darned, gorgeously packaged volume. Let me quote, selfishly, from something that struck me as quintessentially Robb—her ability to unpolish a good woman just a bit, so that we can see ourselves (or perhaps our someday selves) within her. From somewhat late in the book:

People liked or loved you or they didn't, according to their own needs. Not a single night of the months in Maine had she lain awake agonizing over the possibility that she might accidentally have slighted someone, or that she might have exhibited favoritism to some member of the family as opposed to another. She knew perfectly well that she was capable of—and had indulged in—a certain spitefulness now and then, and generally she had apologized. If she happened to slight someone by accident or through ignorance, or just through a failure to rein in her tendency toward bossiness... Well, she no longer tormented herself about it. Her newly hardened indifference was unexpected; it was a state of being that she hadn't known existed.After finishing Being Polite to Hitler, I went back and read my review of The Evidence Against Her. That review begins like this—words that strike me as still utterly relevant and true. Read Robb Forman Dew.

@font-face {

font-family: "Times";

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

Perhaps the only thing more bewildering than gauging one's own mind is imagining the minds of others—the residues and imprints that spark and shadow foreign thoughts. Of all that has happened in a life, what gets remembered, what signifies? Of all the improbable influences, what finally persuades? Those of us who struggle to answer such questions for ourselves have little choice but to admire a writer of the caliber of Robb Forman Dew, who has demonstrated, in both her fiction and her nonfiction, a near savantism when it comes to mapping psychological terrain. Dew's characters are fiercely imagined, fiercely alive on the page—complicated, contradicting, equally prone to shame and to sweet triumphs. No detail is too small for Dew to dwell on or to share. Nothing escapes her formidable and wholly empathetic imagination.

Published on February 13, 2011 11:47

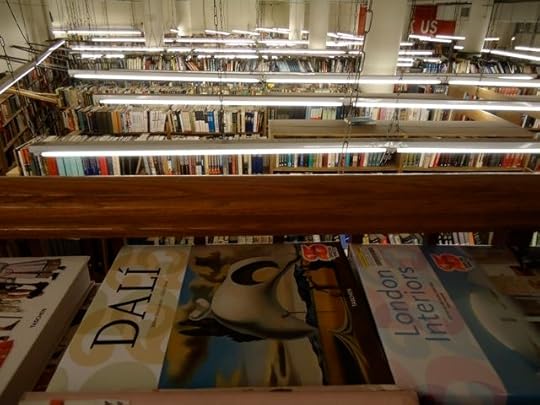

Finding my way to 18 Miles of Books

I had the occasion to walk from the river framing Wall Street up, through the East Village, along Broadway. It was a cold day, but the sun was shining, and I fell in thick with a happy feeling. I had unwittingly dropped one of several things that I'd stuffed inside my coat pocket; a man ran it back to me with grace. I sat alone in a restaurant grading student papers; the waiter was efficient and most kind. I was on my way to meet someone with whom I've had a most cherished correspondence and was at last nearing her building when I saw the Strand Bookstore across the street, at a diagonal. The Strand Bookstore? I ridiculously asked myself, jogging at once toward the red canopy and the fabled bins of one dollar books.

I had the occasion to walk from the river framing Wall Street up, through the East Village, along Broadway. It was a cold day, but the sun was shining, and I fell in thick with a happy feeling. I had unwittingly dropped one of several things that I'd stuffed inside my coat pocket; a man ran it back to me with grace. I sat alone in a restaurant grading student papers; the waiter was efficient and most kind. I was on my way to meet someone with whom I've had a most cherished correspondence and was at last nearing her building when I saw the Strand Bookstore across the street, at a diagonal. The Strand Bookstore? I ridiculously asked myself, jogging at once toward the red canopy and the fabled bins of one dollar books. Opening the door, I was at once engulfed by heavy-coated, floppy-hatted people swarming about tables of books, between the aisles of books, among the dolls and magnets and puppetry inspired by the fantastical or real of books. I was having a bit of a hard time processing it all—I'd only merely happened upon it—and so I climbed the stairs to a mid-point landing to look out upon the vastness. I was snapping this photograph when a young man came and stood beside me—two passengers, we were, on the book balcony of a ship.

"And it goes on," he said, "and on, doesn't it?"

"It absolutely does," I said.

And may it always.

Published on February 13, 2011 05:27

February 12, 2011

Am I not, then, a teacher invested? Do I not engage?

The February 14/21 issue of The New Yorker is full of interesting things (not to mention a very funny/poignant guest piece by Tina Fey; don't miss it), but for this morning's blog I choose to focus on Malcolm Gladwell's essays, "The Order of Things: What College Rankings Really Tell Us." I'll spare you most of the details (though they alarm and intrigue). I'll focus here on one that had a nearly physical impact on me. Gladwell is talking here about the yearly U.S. News college ranking and the algorithms that support it. He has turned his gaze on a category named "faculty resources," which determines twenty percent of an institution's score. Quoting from the College Guide, Gladwell reports, "Research shows that the more satisfied students are about their contact with professors the more they will learn and the more likely it is they will graduate," a conclusion reinforced by student engagement studies and a conclusion nearly any parent will make after watching their children lean toward certain classes and teachers.

The February 14/21 issue of The New Yorker is full of interesting things (not to mention a very funny/poignant guest piece by Tina Fey; don't miss it), but for this morning's blog I choose to focus on Malcolm Gladwell's essays, "The Order of Things: What College Rankings Really Tell Us." I'll spare you most of the details (though they alarm and intrigue). I'll focus here on one that had a nearly physical impact on me. Gladwell is talking here about the yearly U.S. News college ranking and the algorithms that support it. He has turned his gaze on a category named "faculty resources," which determines twenty percent of an institution's score. Quoting from the College Guide, Gladwell reports, "Research shows that the more satisfied students are about their contact with professors the more they will learn and the more likely it is they will graduate," a conclusion reinforced by student engagement studies and a conclusion nearly any parent will make after watching their children lean toward certain classes and teachers. What troubles Gladwell (and what troubles me, not just Gladwell's reader but a faculty member at an Ivy League University who seeks and values student engagement above all else) is how U.S. News has elected to measure this elusive quality. Apparently engagement is determined by the following factors: class size, faculty salary, professors with the highest degree in their fields, the student-faculty ratio, and the proportion of faculty who are full-time. All of which, with the exception of class size (and mine is currently oversubscribed) just about kicks me out of having any shot at all at having a positive statistical impact on the University of Pennsylvania's 'faculty resources' score.

This offends me deeply, and it especially offended me yesterday, having just spent the better part of three days writing notes to my beautiful and (it seems to me) engaged students—notes inspired by the glean of their talents and the nature of their writerly ambitions and the ways in which they work (so hard) toward amplified versions of themselves. I teach because it is an honor to work with those who stand on the verge. I spend the time I spend because I recognize the depth of my responsibility and the abject importance of never rushing past a student who wants more or who struggles for more or could be even more.

Maybe you can't really measure that. But I suspect that my salary and my degree and my part-time status should not, in some machine somewhere, be diminishing the ranking for Penn.

Published on February 12, 2011 07:03