Beth Kephart's Blog, page 252

March 22, 2011

Getting to know you (thoughts on the literary profile)

Today in class, following our review of four student memoirs, we'll look ahead toward the literary profiles that the students will be writing as their final project. My instructions for the assignment are, as usual, simple enough (I include them below). Not quite as simple is shaping, with the students, standards of excellence, or measures against which such profiles might be judged. I loved, for example, Patti Smith's profile of Johnny Depp in a late 2010 issue of Vanity Fair precisely because of the rugged, empathetic nature of her questions; Smith knows fame, she knows yearning, she knows loss, and she knows Depp, and by going beyond what she already knew (by asking the piercing personal and philosophical questions) she gave us an indelible, original portrait.

Today in class, following our review of four student memoirs, we'll look ahead toward the literary profiles that the students will be writing as their final project. My instructions for the assignment are, as usual, simple enough (I include them below). Not quite as simple is shaping, with the students, standards of excellence, or measures against which such profiles might be judged. I loved, for example, Patti Smith's profile of Johnny Depp in a late 2010 issue of Vanity Fair precisely because of the rugged, empathetic nature of her questions; Smith knows fame, she knows yearning, she knows loss, and she knows Depp, and by going beyond what she already knew (by asking the piercing personal and philosophical questions) she gave us an indelible, original portrait.In Misgivings: My Mother, My Father, Myself, the poet C.K. Williams brings psychological acuity and a poet's ability to parse to his intimate renderings of those who shaped his world. We know Williams's mother, for example, by what he tells us she withholds, and why. "When my father was undergoing his illnesses, his absentmindedness, his depressions, (my mother) somehow managed never quite to submit to them: although she sympathized with him, wished he were better, was, you could tell, a little offended without ever saying so by his not being better, she still never manifested what was happening as something that really possessed her; she always kept back that corner of her feelings that might have made her suffer too much."

In her introduction to The Possessed, Elif Batuman yields a portrait of the "first Russian person I ever met" that (by choosing just the right scenes, the right snips of dialogue, the dead-on, tell-tale italics) gives us an immediate sense not just of a man's infuriating but perhaps endearing idiosyncratic tics, but of the effect those tics had on Batuman herself. "Toward the end of one (violin) lesson, for example, he told me that he had to leave ten minutes early—and then proceeded to spend the entire ten minutes unraveling the tortuous logic of how his early departure wasn't actually depriving me of any violin instruction. 'Tell me, Elif,' he shouted, having worked himself up to an amazing degree. 'When you buy a dress, do you buy the dress that is most beautiful...or the dress that is made with the most cloth?'"

Oliver Sacks, especially in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, makes effective use of clinical language and telling dialogue to bring his real-life characters to the page. Frederick Busch uses a novelist's touch—vivid, unexpected details, the lean of impression against the stacking of facts—to invigorate portraits of people like his father and Terrence des Pres. In The Duke of Deception, Geoffrey Wolff juxtaposes known facts against purported ones to give us a man, his own father, who sought to deceive all on every topic save for the power and importance of love.

I'm going to be reading segments from those books to the students today. Additionally, I've asked them to read, on their own, Lynn Hirschberg's New York Times Magazine profile of Lee Daniels, the so-smart, so-sensational, and (to use her word) audacious director/part producer of the Oscar-winning film "Precious" (among other things). The students have downloaded the Hirschberg story (in these waning days of being able to download NYT files, though, hey, I am a paper subscriber and will still have privileges) and, I hope, they've played the video of Daniels on that same NYT site. Does Hirschberg successfully capture the man in the camera's eye? I'll ask. Is his beauty on the page, his way of remembering, the look he gets in his eyes, his deep knowing? If she has succeeded, how? If she hasn't, what more might she have done? Has the right balance been struck between transcript and seeing, research and conjecture, data and impressions?

The assignment, then:

You will be asked to write a literary profile of a person whose work or life is of great interest to you. You will have to conduct at least one in-depth interview of the person him or herself as well as one secondary interview with someone who knows that person (works with them, taught them, is related to them, etc.). The profile subject can be anyone—someone in your family, someone working in a profession of interest to you, a favorite past teacher, a chef, a friend, a work-out king, a bio-engineer, a world traveler, a physician, an actress or actor. But you will have to have a compelling reason for choosing that person. Think of this as an opportunity/excuse to have a conversation with someone with whom you've always wanted to have a long conversation.

Published on March 22, 2011 03:41

March 21, 2011

Let's be honest with each other, at least for a moment

We avoid landmines out here—so many of us (I'm guilty, too) do. Don't say things that might be said, don't help guide a friend toward a new understanding, don't disagree, don't attempt to back another away from an exaggeration or a misappropriation, don't ask for a righting of the balance, because, well, the possibility of a ruckus is just too much to bear. So that we are silent or we are passive; we let things slide. This, in time, leads to dissonance and distance. Another kind of fracture.

We avoid landmines out here—so many of us (I'm guilty, too) do. Don't say things that might be said, don't help guide a friend toward a new understanding, don't disagree, don't attempt to back another away from an exaggeration or a misappropriation, don't ask for a righting of the balance, because, well, the possibility of a ruckus is just too much to bear. So that we are silent or we are passive; we let things slide. This, in time, leads to dissonance and distance. Another kind of fracture.I was thinking about this while reading Geoffrey Wolff's remarkable The Duke of Deception, his memoir about his fraught relationship with his father. I'll be writing more about this book in the days to come, but for now it's this page 10 moment that I share. It's the honesty of Wolff's friend that caught my eye. His willingness to state what he believed to be the truth. More than that: Wolff's willingness to listen.

Writing to a friend about this book, I said that I would not now for anything have had my father be other than what he was, except happier, and that most of the time he was happy enough, cheered on by imaginary successes. He gave me a great deal, and not merely life, and I didn't want to bellyache; I wanted, I told my friend, to thumb my nose on his behalf at everyone who had limited him. My friend was shrewd, though, and said that he didn't believe me, that I couldn't mean such a thing, that if I followed out its implications I would be led to a kind of ripe sentimentality, and to mere piety. Perhaps, he wrote me, you would not have wished him to life to himself, to life about being a Jew. Perhaps you would have him fool others but not so deeply trick himself. "In writing about a father," my friend wrote me about our fathers, "one clambers up a slippery mountain, carrying the balls of another in a bloody sack, and whether to eat them or worship them or bury them decently is never clearly decided."

So I will try here to be exact....

Published on March 21, 2011 17:49

I wanted proof of winter's thaw

Published on March 21, 2011 03:33

March 20, 2011

In their silken capes, with their plastic swords

They came to save the world.

They came to save the world.(A scene from Valley Forge Park, where earlier today, after taking our boy back to his bus and studying this week's student memoirs, I went to take a two-hour hike. I saw green, and I saw birds. I'll share both with you later this week.)

Published on March 20, 2011 18:58

Spoken Word Artist Sarah Kay

Late last week, Rachel (a student full of fire, zest, talent; a student unafraid to call another student's writing perfect) sent this along to her classmates and to me, saying: I thought this was beautiful.

It is. It's Sarah Kay, a spoken word artist, performing and talking about what performing and talking (and teaching performing and talking) can mean. A Sunday afternoon treasure, should you have the time. The full link to this TED presentation is here.

Published on March 20, 2011 10:59

when the moon is an abstraction

Published on March 20, 2011 04:01

March 19, 2011

stepping out (a few upcoming events)

I am notoriously bad at looking too far ahead, but there are times when, well, I must. And so, just now, my son tucked into a nearby room reading up on the six-day war, I survey the days ahead.

I am notoriously bad at looking too far ahead, but there are times when, well, I must. And so, just now, my son tucked into a nearby room reading up on the six-day war, I survey the days ahead.A few places I intend to be:

Thursday, March 31, 2011/The Willows/7 PM

Radnor High School Scholarship Fund 4th Annual Girls' Night Out (a talk, with photographs)

Saturday, April 9, 2011/Mt. Airy Kids' Literary Festival/Big Blue Marble Bookstore/3 PM

Reading/Talk with Kate Milford

Thursday, April 28, 2011/Conestoga High School/AM

Talk with Teachers/Talk with Students

Central League Writing Contest (closed to school participants and teachers)

Wednesday, May 25, 2011/Javitz Center/BEA/afternoon

Assorted Events

Friday, May 27, 2011

Agnes Irwin Writing Workshop

Saturday, June 25, 2011/Chanticleer Garden

A talk and luncheon with San Francisco's Fabulous (I call them that) Traveling Book Club

(with thanks to Kathye)

Published on March 19, 2011 14:52

sometimes you just have to stop the madness and be a girl

Published on March 19, 2011 14:19

Townie/Andre Dubus III: Full Reflections

I finished reading Townie today, a book I first wrote of a week or so ago. It is a long book, not one to be rushed through. It is a hard book, a tale about the fate of children growing up in the wake of an occasional dad—a talented man, a loving man, but a man who puts his impulses and his writing first. Dubus II, the author's father has, we come to realize (thanks to the son's tender and non-accusatory telling), no real idea why his children are hungry or chased or being hurt in the world, or why his namesake son doesn't know how to throw a ball, or why that same son turns to beefing up and boxing and lashing out at world that can do tremendous harm.

I finished reading Townie today, a book I first wrote of a week or so ago. It is a long book, not one to be rushed through. It is a hard book, a tale about the fate of children growing up in the wake of an occasional dad—a talented man, a loving man, but a man who puts his impulses and his writing first. Dubus II, the author's father has, we come to realize (thanks to the son's tender and non-accusatory telling), no real idea why his children are hungry or chased or being hurt in the world, or why his namesake son doesn't know how to throw a ball, or why that same son turns to beefing up and boxing and lashing out at world that can do tremendous harm.Dubus II doesn't really understand and Dubus III doesn't really want to blame him, but the life was what the life was—a sister's rape, a brother's suicide attempts, a house open to itinerants and bullies, and a single mom doing everything she can to try to hold it altogether, though who can hold it altogether, really, when the four kids are your responsibility and you're working all day just to pay the rent? Leaving brings all kinds of heartache in its wake, and Townie does an extraordinary job of taking us inside the fractures and consequences. It's not that Dubus II doesn't see his kids; a couple of nights a week he does. It's not that he doesn't pay child support; he gives what he can. It's just (but not simply) that none of that, in this family, is enough. Townie hurts to read, but it's essential.

Dubus III, as I have mentioned, overcomes the embattled nature of his adolescent circumstance by clinging to the faith that the only defense he has (for himself, for his family) is muscle and fist. Time and again we see this kid (and, later, this man) throwing a sucker punch, knocking an enemy to the ground, riding in the back of a police car, sitting briefly behind bars, and hearing, later, that one of his victims was sent to the hospital, that one of the victim's friends is out to get him. Later in life, Dubus II, a former marine, asks his son how he can take so many assailants on at once, and the author, by way of explaining, says this:

I wanted to tell him about the membrane around someone's eyes and nose and mouth, how you have to smash through it which means you have to smash through your own first, your own compassion for another, your own humanity.This idea—this history of smashing through his own humanity—haunts Dubus III throughout these pages. We are haunted with him. Seamlessly and urgently written, no boast in it, no politics, no accusations, either, Townie is a reckoning. It is a brave insider's look at how one moves past fists toward words, past heartbreak toward compassion, past broken family to a wholeness of one's own.

Published on March 19, 2011 07:18

March 18, 2011

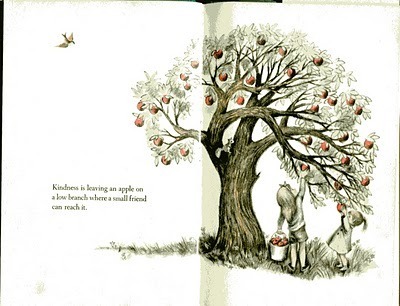

Kindness is a lot of things

I was racing through the late part of this morning—cleaning the house, buying more flowers, hurrying up and down the aisles of the Farmer's Market in search of my father's favorite foods. I arrived home with ten minutes to spare, arranged the things on the table, hurried down the hall, and opened the door: He was there.

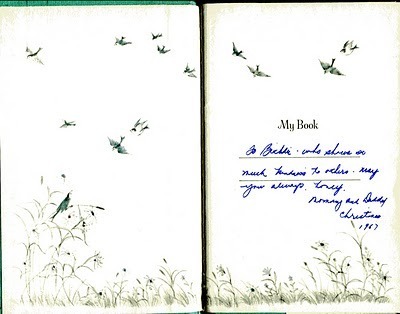

I was racing through the late part of this morning—cleaning the house, buying more flowers, hurrying up and down the aisles of the Farmer's Market in search of my father's favorite foods. I arrived home with ten minutes to spare, arranged the things on the table, hurried down the hall, and opened the door: He was there.My father has been looking through my mother's books—her first editions of F. Scott Fitzgerald, her signed Ulysses S. Grants, her Maxfield Parrish pages. In the midst of it all, he found this, an early gift that my mother had given to me. It was a book about kindness. Those are her words, written to me.

A reminder. And also one more sign of how dearly my father continues to carry her spirit forward.

Published on March 18, 2011 12:23