Beth Kephart's Blog, page 212

November 18, 2011

News

It's extraordinary how kind the world (despite all else, despite everything) still can be.

At the end of this week, at the end of this day—the light dying toward that most exquisite pink, gold above the pink, blue layered into the gold—I want to celebrate:

My dear students, who write with their great good news. You can't see me when I get your messages, but I am ear-to-ear with happiness for you.

My neighbor Kathleen, one of the most gorgeous, green-eyed women you will ever see, who has welcomed a great-granddaughter into the world.

My friend Mike, for reminding me (all the way from Nyon) of the power of 90-minute lunches.

My father, for gifts, large and small.

My husband, for a Wednesday night salsa.

My son, for right this minute being on a bus headed my way.

And those rare souls—rare and deeply good—who make a place for others in this world. You know who you are. I lift a sky-filled glass to you.

Published on November 18, 2011 13:59

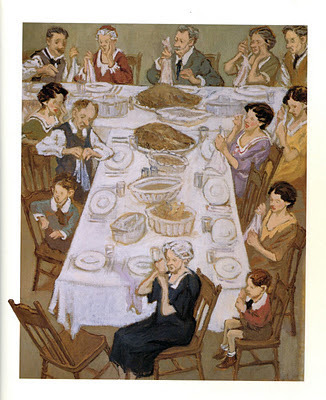

The Thanksgiving Visitor/Truman Capote (illustrated by Beth Peck)

I've had a heck of a morning working on highly technical client stories (I think I got up just a tad too early for this stuff, even for me) and I—well, I needed a break. So I went to my shelves and dug out one of my favorite Truman Capote stories, The Thanksgiving Visitor, illustrated by Beth Peck.

It always softens my edges, this well-spun tale about Buddy and his closest friend, Miss Sook, who is not just a friend but an elderly cousin. They're getting ready for a big Thanksgiving meal and everything is just fine this November 1932 until Miss Sook decides that Buddy should invite his nemesis, Odd Henderson, for the turkey meal. Capote is in fine form throughout the story. Here's our first glimpse of Odd:

Tall for his age, a bony boy with muddy-red hair and narrow yellow eyes, he towered over all his classmates—would have in any event, for the rest of us were only seven or eight years old. Odd had failed first grade twice and was now serving his second term in the second grade. This sorry record wasn't due to dumbness—Odd was intelligent, maybe cunning is a better word—but he took after the rest of the Hendersons. The whole family (there were ten of them, not counting Dad Henderson, who was a bootlegger and usually in jail, all scrunched together in a four-room house next door to a Negro church) was a shiftless, surly bunch, every one of them ready to do you a bad turn; Odd wasn't the worst of the lot, and brother, that is saying something.

The question is frequently asked: Who are children's books for? I say the best of them are for all of us, at every age. And I can't think of a better family tale for this time of year than The Thanksgiving Visitor.

Published on November 18, 2011 06:37

November 17, 2011

why we read

This was one crazy Beth day (there's a picture of me, being crazy). Somewhere in the middle of it (between writing a chapter of the novel, rushing, with my husband, to procure the various food stuffs that our soon-to-be-home-for-a-week son will no doubt yearn for, and finishing up the second draft of a client project), I pulled a substantial portion of my personal library to the floor in search of a Roland Barthes book—Camera Lucida. I still can't find it. I might just have to buy another copy.

I did, however, discover (the book tumbling out onto the floor) A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel. When it fell, it fell open to the passage below. It seemed a sign. I share it:

We read to understand, or to begin to understand. We cannot do but read. Reading, almost as much as breathing, is our essential function.

Published on November 17, 2011 15:41

you know how much I love to dance

(of course you do).

You can therefore imagine my distinct happiness when I learned that our son has chosen—the final course he will choose at a university he has loved—to take a ballroom dancing class. Just a little one-credit something to cap a remarkable four years.

The photo above is not of my son, but it is of a boy whom I adored back in the days when I was volunteering as a judge and photographer for Dancing Classrooms. A video montage from that experience (with words and music) can be found here.

Published on November 17, 2011 05:03

November 16, 2011

Birds of Paradise, Diana Abu-Jaber, and writing what you love

Skyscape. Choreography. Color. Birds. I have carried these obsessions forward since I first began to write so many years ago. A story begins, and I want to go there. Want to write what I love most to write, though (of course) no story can consist of just these things. They are but atmosphere.

I have been thinking about this lately because I have been reading Diana Abu-Jaber's new novel Birds of Paradise—an ambitious book featuring multiple points of view, the business of real estate, the artistry of exotic pastries, and a run-away teen. Much is broken and strained in this family and Abu-Jaber takes her readers into complex emotional territory as the story unfolds.

But what seduces me most throughout this novel is the command that Abu-Jaber demonstrates for Miami. Her knowledge of this landscape is unimpeachable, her ability to get us into the physical stuff of it all her great achievement in Birds of Paradise. I could almost hear her exhale when the landscape came into view—the gardens, the streetscapes. I could feel her joy in making these scenes.

I share a single example:

The scent of jasmine drifts into the windows. Songbird season is over. No more gardenias: hurricane season. The trees have grown dense as rooftops; the plumeria hold their flower-tipped branches up like brides with golden corsages. Avis sits hunched forward, clinging to her tin: she can feel the metal chill through her blouse, all the way to the pit of her stomach. She'd forgotten to eat again.

Published on November 16, 2011 09:07

November 15, 2011

The Grievers/Marc Schuster: Reflections and Blurb

When Marc Schuster slipped a copy of his new book my way a few weeks ago, I looked at the cover (lovely), considered the title (The Grievers), and read the first line of the jacket copy:

The Grievers is a darkly comic coming of age novel for a generation that's still struggling to come of age.

This Marc Schuster, I thought to myself, has a sense of humor.

Having just this afternoon finished my read of this slender book (due out on 5/1/12 from the Permanent Press), I feel the urgent need to correct myself. This Marc Schuster has a gigantic sense of humor. I kept trying to think of comparators as I read. The Big Chill meets Old School. A Separate Peace or Dead Poets Society, if either had been authored by Jon Stewart. Waiting for Alaska, except for adults, and with a different plot.

Honestly, I'm so bad at that sort of thing.

Here's the set-up. I don't think any of you have ever seen me place actual jacket copy front and center, but since I suspect that The Sublimely Funny Schuster wrote this copy, I just have to share it as is:

When Charley Schwartz learns that an old high school pal has killed himself, he agrees to help his alma mater organize a memorial service to honor his fallen comrade. Soon, however, devastation turns to disgust as Charley discovers that his friend's passing means less to the school than the bottom line. As the memorial service quickly degenerates into a fundraising fiasco, Charley must also deal with a host of other quandaries including a dead-end job as an anthropomorphic dollar sign, his best friend's imminent move to Maryland, an intervention with a drug-addled megalomaniac, and his own ongoing crusade to enforce the proper use of apostrophes among the proprietors of local dining establishments.....

Yes. That's right. An anthropomorphic dollar sign. It has glitter, people. It sheds. Charley Schwartz hobbles around inside it, conducting this memorial-making business by phone. The phone? It too is a character in The Grievers. I'm now quoting from the book itself:

Through no fault of my own, my cell phone played the theme from The Jeffersons whenever I received an incoming call, so when Neil got back to me, the sweaty silence of my big, boxy costume was broken by the sound of a gospel choir singing about moving on up to the East Side, to a deluxe apartment in the sky.

Seriously.

Marc was hoping I might be able to blurb his book, but as you can tell, I'm having too much fun quoting from it. I will stop for just a moment then, and conclude this blog post like this: The Grievers is a work of astute perception, high-octane imagination, and utterly supple prose. Raging cluelessness has never been this funny or, in the end, this compassionate.

Published on November 15, 2011 15:27

Jill Lepore, Ben Franklin and his Sister, and an Invitation to an Evening at Villanova University

On December 6, 2011, starting at 7 PM, Jill Lepore will join hundreds of students, faculty members, and university neighbors in the Villanova Room of the Connelly Center. I'm extremely proud that Dr. Lepore represents the third speaker in The Lore Kephart '86 Distinguished Historians Lecture Series, an annual event that my father created in memory of my mother, who graduated in the top of her Villanova University class following a college career that was not initiated until she had raised her three children.

Dr. Lepore's talk is titled "Poor Jane's Almanac: The Life and Opinions of Benjamin Franklin's Sister," with the further subtitle: "an 18th century tale of two Americas." We get some hint of the fascinating content to come in this New York Times op-ed piece, which appeared on April 23, 2011. I am excerpting at length, and I hope to be forgiven:

Franklin, who's on the $100 bill, was the youngest of 10 sons. Nowhere

on any legal tender is his sister Jane, the youngest of seven daughters;

she never traveled the way to wealth. He was born in 1706, she in 1712.

Their father was a Boston candle-maker, scraping by. Massachusetts'

Poor Law required teaching boys to write; the mandate for girls ended at

reading. Benny went to school for just two years; Jenny never went at

all.

Their lives tell an 18th-century tale of two Americas. Against poverty

and ignorance, Franklin prevailed; his sister did not.

At 17, he ran away from home. At 15, she married: she was probably

pregnant, as were, at the time, a third of all brides. She and her

brother wrote to each other all their lives: they were each other's

dearest friends. (He wrote more letters to her than to anyone.) His

letters are learned, warm, funny, delightful; hers are misspelled,

fretful and full of sorrow. "Nothing but troble can you her from me,"

she warned. It's extraordinary that she could write at all.

"I have such a Poor Fackulty at making Leters," she confessed.

He would have none of it. "Is there not a little Affectation in your

Apology for the Incorrectness of your Writing?" he teased. "Perhaps it

is rather fishing for commendation. You write better, in my Opinion,

than most American Women." He was, sadly, right.

She had one child after another; her husband, a saddler named Edward

Mecom, grew ill, and may have lost his mind, as, most certainly, did two

of her sons. She struggled, and failed, to keep them out of debtors'

prison, the almshouse, asylums. She took in boarders; she sewed bonnets.

She had not a moment's rest.

And still, she thirsted for knowledge. "I Read as much as I Dare," she

confided to her brother. She once asked him for a copy of "all the

Political pieces" he had ever written. "I could as easily make a

collection for you of all the past parings of my nails," he joked. He

sent her what he could; she read it all. But there was no way out.

Dr. Lepore, whose work in The New Yorker always thrills me and whose mind seems to track one curiosity after the other—Charles Dickens, Planned Parenthood, the Tea Party, Stuart Little, (she's even got a co-authored novel to her name)—is the David Woods Kemper '41 Professor of American history at Harvard University. She follows Pulitzer Prize winning James McPherson and the utterly engaging Andrew Bacevich as a Distinguished speaker in the series.

This event is free and open to the public, but registration is recommended, given the large turnout we are blessed with each year. Here, again, are the facts:

Jill Lepore, PhD

Poor Jane's Almanac: The Life and Opinions of Benjamin Franklin's Sister

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

7 PM

Villanova Room, Connelly Center

http://www.villanova.edu/events/lectu...

I hope to see you there. I'll be in the front along with family and friends.

(The photo, by the way, is in honor of the fact that Benjamin Franklin was key among those early environmentalists who fought to preserve the Schuylkill and her drinking water.)

Published on November 15, 2011 05:01

November 14, 2011

Blue Nights/Joan Didion: Reflections

I was harder on Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking than many readers were. I thought it at times too self-consciously clinical, too reported, less felt. Many of my students at the University of Pennsylvania disagreed with me. I listened. Of course I did. I wanted to be convinced.

I do not feel disinclined about Blue Nights, which I have read this morning and which will break your heart. The jacket copy describes the book as "a work of stunning frankness about losing a daughter." It is that; in part it is. But it is also, mostly, as the jacket also promises, Didion's "thoughts, fears, and doubts regarding having children, illness, and growing old."

A cry, in other words, in the almost dark. A mind doing what a mind does in the aftermath of grief and in the face of the cruelly ticking clock. Blue Nights is language stripped to its most bare. It is the seeding and tilling of images grasped, lines said, recurring tropes—not always gently recurring tropes. It is a mind tracking time. It is questions:

"How could I have missed what was so clearly there to be seen?"

"What if I can never again locate the words that work?"

"Who do I want to notify in case of emergency?"

Joan Didion, always physically small and intellectually giant, is, as she writes in this book, seventy-five years old. She is aware of light and how it brightens, then fades. She writes of blue—a color and a sound that has long obsessed me, and has obsessed writers like Rebecca Solnit. She writes of the gloaming, a word I will forever associate with the immensely talented Alice Elliott Dark.

Here is how she writes:

You pass a window, you walk to Central Park, you find yourself swimming in the color blue: the actual light is blue, and over the course of an hour or so this blue deepens, becomes more intense even as it darkens and fades, approximates the blue of the glass on a clear day at Chartres, or that of the Cerenkov radiation thrown off by the fuel rods in the pools of nuclear reactors. The French called this time of day "l'heure bleue." To the English it was "the gloaming." That very word "gloaming" reverberates, echoes—the gloaming, the glimmer, the glitter, the glisten, the glamour—carrying in its consonants the images of houses shuttering, gardens darkening, grass-lined rivers slipping through the shadows.

Published on November 14, 2011 06:36

November 13, 2011

After the Storm: the documentary you must see

I have written many times here about my dear friend James Lecesne. I have written about his talents, his kindness, his soul. James stands behind the renowned and supremely humane Trevor Project—"determined to end suicide among LGBTQ youth by providing life saving and life-affirming resources." (Click here to watch Harry Potter's own Daniel Radcliffe talk, with James, about Trevor.) James also, as you know if you read this blog, was a pivotal force behind "After the Storm"—an arts-based initiative, a documentary film, and an ongoing effort to support the young people of Katrina-ravaged New Orleans. "After the Storm," not incidentally, is also full-on proof that the faith we place in the arts is wise and fertile.

I have watched the "After the Storm" trailers for a long time (repeatedly!), read the reviews, talked to James. But yesterday my own copy of the DVD arrived. Bill and I ate an early dinner so that we could sit and watch it.

This, my friends, is a movie that can change your life. This is also an opportunity to make a difference by investing in a DVD you will watch again and again.

Please do.

Published on November 13, 2011 08:33

November 12, 2011

The writing is in me just now (an urgent thing on a quiet day)

Published on November 12, 2011 08:39