Beth Kephart's Blog, page 201

February 2, 2012

research yourself, research your fiction, know more

I confess to a certain panic. Its causes are many, but here is one: It is difficult for me to find the time to write, and when I do find that time, I am not writing. I am reading the books that no one has checked out of Van Pelt Library for a very long time (ever?). I am listening to old and scratchy German songs recorded (who knows why) on YouTube. I am going blog by blog until I find (miraculously!) a photograph of a street corner that I walked once but cannot now remember.

I may be writing a novel, but if you were to see my office (though please don't; its disarray could offend you), you would see how it is: the books that surround me are not my own.

Two years ago, I gave a talk about the research that underpins all my work—memoir, fable, fiction, poetry. I was remembering this passage of the talk today. Consoling myself (for I need to be consoled) about the slow, slow, slow of my writerly process.

Whether

I'm writing memoir or novels, fables or poems, novels for adults or for young adults, I am, at one point, reaching far beyond myself to bring

the greater world in. I am

following the always persistent, hardly consistent, rarely well-tiled path of

my insatiable curiosity. True,

research is often either a surfeit of overwhelm, or a tease. Still, and nevertheless, I don't

believe in bringing presumption to the page—in writing simply and only what I

already know. I don't believe in

closing doors before I've opened windows.

I want to be alive when I am writing—engaged, in suspense, full of the

unprotected what ifs? I want to

convey my own surprise, dismay, or basic indignity right there, on the page. Formulas don't cut it for me. Formulas have been done. Research scrambles the math.

Published on February 02, 2012 09:43

February 1, 2012

the amaryllis blooms

Because the day was suddenly too hard, too jagged-edged, too full of requests, I stopped, walked toward the sun, and took some photographs.[image error]

Published on February 01, 2012 14:48

I write like I do because

There are those who question my decision (always) to write my full heart out for teens—to go as far as I can with language, meter, idea. To stretch, break, coalesce, pause. "But they are teens," I'm told, which is to say, "but they are young." Which is to say, "Keep it simple."

I can't. I believe so fully in the minds and hearts of teens precisely because I teach them, I work with them, I receive their work through the mail, I know what they themselves can do and do do with language. They don't box words in. Why should I?

My case in point today is this fragment of a poem sent to me by a former neighbor, a woman who is still a dear friend and writing confidant. My friend didn't write this poem, though. Her teenaged daughter did. Not simple. But beautiful. These are the opening lines.

Drawn and quartered. You divided

me. You were all four horses,

manes black as power

your foaming mouths and tense bodies were

beautiful to me

even then. (even now but

never mind)

You were all four hands on all four

whips. You were north

and east and west and

south as they dragged me away.

I had to decide where

to die.....

Aimee Seu, "The Decision"

Published on February 01, 2012 05:00

January 31, 2012

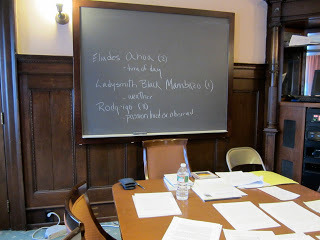

scenes from the (teaching and commuting) day

Published on January 31, 2012 17:34

Penetrating the familiar with Ladysmith Black Mambazo

"Penetrating the familiar is by no means a given. On the contrary, it is hard, hard work."

— Vivian Gornick, The Situation and the Story

We're talking about we get there today at Penn. Among other things, we're listening to Ladysmith Black Mambazo to learn what isicathamiya can teach us about our own weather, and about the way we perceive it.

Published on January 31, 2012 06:07

January 30, 2012

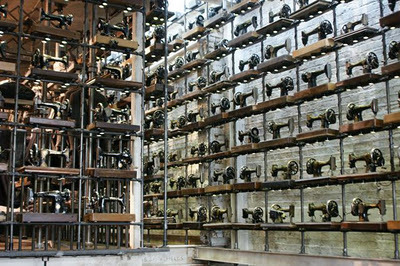

Lilian Nattel's Web of Angels Arrives

Whenever I see a sewing machine, I take a picture for my dear friend, Lilian Nattel, a Canadian author and blogger who delights me with her wide-ranging world view, astute critical mind, and literary talents. She makes things, this Lilian. Seams stories together and fabrics, too. Lives the broad, bright life.

I've been saving this photograph, then, (snapped in November on Portobello Road in London) for a long while, for I knew that someday soon I'd have a chance to celebrate Lilian's new book on my blog.

That day is today. Or, I should say, the celebration begins today, for galleys of Web of Angels, Lilian's novel about, among other things, dissociative identity disorder, have just arrived on my doorstep.

All I had to do was read the first two sentences to know that I was about to enter a compelling, well-drawn world. I'll leave you with those and return in a few days with a full report:

On a narrow street in the grey of dawn, in a row house with stained glass, a sixteen-year-old girl lay motionless. Her hair was blone, short, gelled in spikes, her legs unshaven, her pink nightgown straining over a nine-month belly.

Published on January 30, 2012 07:10

January 29, 2012

Father's Day/Buzz Bissinger: reflections on a most remarkable book

Every morning, minus the nights I never went to sleep in the first place, I do the same thing, robotic and dull: Open the door to my office (the temperature there the same as the temperature outside), slump toward my desk, fold into my chair, ping the computer, shiver or sweat (according to the season), and await my email. It's the wearisome habit of the perennially self-employed. I take care of my clients first. And then, if there's room left over, I make room for the day.

I didn't do that this Sunday morning. The thought (and this, I swear, is historic) never occurred. Because I had gone to sleep reading Buzz Bissinger's Father's Day, and, on waking, I was so wild in my want to finish the book that habit had no power over me. Subtitled A Journey Into the Mind & Heart of My Extraordinary Son, Buzz's book is a memoir about fatherhood and about a trip he took with his adult son, a second-born twin named Zach. Read the flap copy and you'll know why the story—about not wanting and getting, about bewilderment and exhilaration, about doing wrong and being wronged and loving hard and forever—should be important. Read the book to find out why it (absolutely, you-can't-deny-me-this) is.

"What is most irreducibly true about you?" I asked my memoir class at Penn last Tuesday. Memoirs fail, I told the kids, emphatic, when they lack compassion for both the subject and the self. Take risks, I told them. Be original; it's your one life. Care about language, go raw and interesting, don't be afraid to get it wrong, because if you do, you have a crack at getting it right. Be unafraid and perhaps, I meant to say if I didn't say, you'll write the true impossible mess of life.

I should have had Buzz's book in hand while I gave my talk. I would have read my beautiful students every word of this most moving, most meaningful, most wrenching, most clear, most important memoir, Father's Day. I am proudly Buzz's friend, and I know he struggled with this book, but on every page is proof of how an honest struggle, a desperate wrestling down, can at times yield a book that will be read for ages by all ages—not just for the story and for the wisdoms (which are many, accruing, and right), not just for the language (which is gorgeous as it both lances and limns), not just for the perfectly constructed asides that teach us the history of premature babies and savants, but also, if you want to get technical about it, for the structure. Father's Day is a perfectly structured book. And it's funny and it's sad and it moves you and it's honest. Maybe Buzz thinks the world is going to remember him for Friday Night Lights, and of course the world will. But Buzz Bissinger, I have news for you: You have just written your most transcendent book. You had all the words you ever needed. They were always waiting for you.

Buzz isn't the easiest guy in the world. Hell. He knows that. Indeed, Buzz uses his own trenchant bitterness, his temper, his neediness, his incompleteness to explore his relationship to his son Zach, who is a map-obsessed, calendaring-gifted, birthday-remembering, tender-hearted man who is loved by many but stymied in the land of The Normals, as Buzz puts it, by a low IQ thanks to a difficult, oxygen-deprived birth. Time and time again as Buzz and Zach weave their way across the country remembering the past together, Buzz is wrong and Zach is right. And Buzz is the kind of father who, after nursing his wounds, relishes that fact. Buzz is a bestselling Pulitzer Prize winner; sure he is. But what we love about Buzz after reading Father's Day, is who he is as a dad. Fallible, funny, trying, hurt, and loving the hell out of his sons.

I want to quote the entire book. I can't. I want to choose a single passage. I find, for the first time ever on this blog, that I can't do that either. If I choose Buzz writing landscape, then I ignore Buzz flailing in a motel room. If I choose Buzz at an amusement park with Zach, then I lose the scene in Las Vegas. If I quote Zach, then I don't get to quote Gerry, the twin who was born three minutes ahead and who is, Buzz writes, Buzz's very soul.

I can't choose, and so I won't. Buy the book when it comes out in May.

[image error]

Published on January 29, 2012 08:01

January 28, 2012

Father's Day: The Buzz Bissinger Memoir

My friend Buzz Bissinger has been at work on an important book for a long time. It's a memoir called Father's Day: A Journey Into the Mind & Heart of My Extraordinary Son. It will appear in mid-May from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, and for Buzz—the Pulitzer Prize winner, the New York Times bestseller, the Friday Night Lights guy, the Vanity Fair contributing editor, the man so often in the spotlight—it's more than a book. It's a reckoning.

My galley copy just arrived. I'm eager to settle in. Between now and the time I report back to you, I share this flap copy with you.

This story, I think, argues to be read.

Buzz Bissinger's twin sons were born three and a half months

premature in 1983. Gerry weighed one pound and fourteen ounces, Zachary

one pound and eleven ounces. They were the youngest male twins ever to

survive at that time at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, the

nation's oldest. They were a medical miracle, but there are no medical

miracles without eternal scars.

They entered life three minutes--and a world--apart. Gerry, the

older one, is a graduate student at Penn, preparing to become a teacher.

His brother Zach has spent his life attending special schools and

self-contained classrooms. He is able to work menial jobs such as

stocking supplies. But he'll never drive a car, or kiss a girl, or live

by himself. He is a savant, challenged by serious intellectual deficits

but also blessed with rare talents: an astonishing memory, a dazzling

knack for navigation, and a reflexive honesty which can make him both

socially awkward and surprisingly wise.

One summer night, Buzz and Zach hit the road to revisit

all the places they have lived together during Zach's 24 years. Zach

revels in his memories, and Buzz hopes this journey into their shared

past will bring them closer and reveal to him the mysterious workings of

his son's mind and heart. He also hopes it will help him to better come

to grips with the radical differences in his beloved twin boys,

inverted mirrors of one another when defined by the usual barometers of

what we think it means to be successful.

As father and son follow a pinball's path from

Philadelphia to LA, they see the best and worst of America and each

other. Ultimately, their trip bestows a new and uplifting wisdom on

Buzz, as he comes to realize that Zach's worldview, as exotic as it is,

has a sturdy logic of its own, a logic that deserves the greatest

respect. And with the help of Zach's twin, Gerry, Buzz learns an even

more vital lesson about Zach: character transcends intellect. We come to

see Zach as he truly is—patient, fearless, perceptive, kind, a sixth

sense for sincerity. It takes 3,500 miles, but Buzz learns the most

valuable lesson he has ever learned.

His son Zach is not a man-child as he so often thought, but the man he admires most in his life.

[image error]

Published on January 28, 2012 10:21

January 27, 2012

Adam Gopnik on prison silence

My tremendous respect for Adam Gopnik, a New Yorker staff writer,

is well known by readers of this blog. Gopnik seems preternaturally

equipped to take on any topic and make it both new and compelling. He

astonishes me with his breadth and depth—writing gloriously, absolutely,

but never sacrificing idea to style.

This week Gopnik has a New Yorker essay entitled "The Caging of

America: Why do we lock up so many people?" He's talking about

process, procedure, and principles here. He is raising the twin issues

of common sense and compassion. He is suggesting, among other things,

that "the scale and the brutality of our prisons are the moral scandal

of American life." He is reporting that, for example, more than four

hundred teens are serving life sentences in Texas, and that "more than

half of all black men without a high-school diploma go to prison at some

time in their lives." He continues: "Mass incarceration on a scale

almost unexampled in human history is a fundamental fact of our country

today—perhaps the fundamental fact, as slavery was the fundamental fact of 1850."

We have to think harder, after reading this story. We have to

investigate our personal prison politics. We have to read again, and

imagine:

[image error]

That's why no one who has been inside a prison, if only for a day, can

ever forget the feeling. Time stops. A note of attenuated panic, of

watchful paranoia—anxiety and boredom and fear mixed into a kind of

enveloping fog, covering the guards as much as the guarded.

Published on January 27, 2012 16:07

the glory we give to ourselves

The downpour here has lifted. There's a buzz of gold coming in from the north. I've been writing, happy, all morning. Give me two hours of uninterrupted time—three if you want to slide me right on up the heavenly stairs. Give me time, and my mood is glory.

We talk too much, out here, about the business of being published. About the size of contracts, the size of tours, the ways in which houses show their faith. It's easy to get caught up in the details, too easy to feel slighted or less than. Hey, I've been there. I know.

But if we let all that get to us we let the wrong forces win. We forget the radiance that comes from the writing itself. From putting the words down, one after the other. From watching as a story reveals itself. One feels the mind spiraling out, Milky Way style. One feels the fresh spray of paint.

That's being alive. That's the good that we give to ourselves.

Published on January 27, 2012 07:22