Beth Kephart's Blog, page 171

August 5, 2012

Adding two new books to my scattershot world, including A Northern Light

I was escaping on Thursday as I made my way to the bookstore. The heat, a particular conversation, a pedigreed failure. In the summer, at bookstores, I tend to stand among those tables dedicated to middle- and high-school reading lists—looking at all that I've missed, scorning my own piecemeal education, regretting my only partially successful autodidactism. I studied the history and sociology of science at Penn. I teach memoir. I review (mostly) adult literary fiction. I have (most recently) been writing young adult fiction that is perhaps not really young adult fiction. I started out as a poet. I am currently researching the heck out of Bruce Springsteen. My triple-stacked bookshelves reflect my scattershot world. Despite the fact that I have tried, since I was a teen, to read at least three books a week (and, later in life, The New Yorker, New York Times, Newsweek, Vanity Fair, and the book review sections of The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, and the Philadelphia Inquirer), I have a whole lot of gaps, always, to fill. I am embarrassed, often, by my own not-knowingness. I could not pass any test that might be given.

Thursday, ignoring the criminally ignored two dozen as-yet-unread books stacked on my office floor, I bought two more—A Northern Light, which Melissa Sarno recommended, and Truman Capote's In Cold Blood. I have read all of Capote except In Cold Blood. Don't ask why; it just happened.

Yesterday, between bouts of Springsteen research, I read A Northern Light, a young adult novel written by Jennifer Donnelly, which was a Printz Honor Book when it was released ten years ago, earned numerous additional citations, and continues to be extremely well read today. Set in 1906 and featuring Mattie, a sixteen-year-old farm-bound girl who loves words, A Northern Light is, I found, an instructive book—thoroughly researched, strategically structured, seeded with the right kind of issues for young readers of historical fiction (feminism, race relations, the value of education and literature). I loved, most of all, Donnelly's Weaver, an African American adolescent. Weaver has much to say, and Donnelly, wisely, gives him room—to be smart, to be angry, to be hopeful, to be Mattie's truest friend. Boy-girl friendships that are honest and meaningful and yet not tinged with erotic desire are so rare in books, and especially rare in young adult literature, and so I was happy to spend some time on this warm weekend making this acquaintance.

Published on August 05, 2012 06:57

August 4, 2012

today, I give this song to those I love

Published on August 04, 2012 12:00

David Eagleman reviews The Storytelling Animal by Jonathan Gottschall

Have I ever mentioned (oh, yes, I know I have) how much I love the book section of the Gray Lady? I start looking for the online version of the coming Sunday's edition on Thursday, even though it's most often not posted until late Friday afternoon. I scan the headlines on my computer once the edition is posted, then take my pink-covered iPad to a safe place and tap in.

Often I return to the old Mac to shout out a favorite couple of passages. Last week I was talking about Judith Warner's review of Madeline Levine's Teach Your Children Well. Today I'm sharing two passages from David Eagleman's review of The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make us Human, a Jonathan Gottschall book. We readers and writers like to talk about these things. We like to agree or not agree.

I rather like, here, that stories have been declared as important as genes. I like that they aren't time wasters. And you?

But not all stories are created equal. Gottschall points out that for a

story to work, it has to possess a particular morality. To capture and

influence, it can’t be plagued with moral repugnance — involving, say, a

sexual love story between a mother and her son, or a good guy who

becomes crippled and a bad guy who profits handsomely. If the narrative

doesn’t contain the suitable kind of virtue, brains don’t absorb it. The

story torpedo misses the exposed brain vent. (There are exceptions,

Gottschall allows, but they only prove the rule.)

This leads to the suggestion that story’s role is “intensely

moralistic.” Stories serve the biological function of encouraging

pro-social behavior. Across cultures, stories instruct a version of the

following: If we are honest and play by the social rules, we reap the

rewards of the protagonist; if we break the rules, we earn the

punishment accorded to the bad guy. The theory is that this urge to

produce and consume moralistic stories is hard-wired into us, and this

helps bind society together. It’s a group-level adaptation. As such,

stories are as important as genes. They’re not time wasters; they’re

evolutionary innovations.

Published on August 04, 2012 06:44

August 3, 2012

Bruce Springsteen: I watch this, I listen to this, I cry

I'm back from a brief interlude at the Jersey Shore. I'm steeping myself in Bruce Springsteen. No more putting this off, no more being afraid. I've got to write my Glory Days paper.

I will need more words than I have.

I will need to watch this again and again.

Published on August 03, 2012 10:16

August 2, 2012

Landscape, Soul, Story: An Interview, A Review

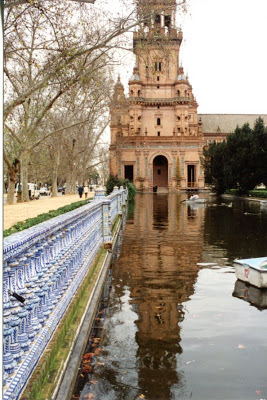

A few weeks ago, Tamara Smith, the co-creator of Kissing the Earth (you will love this site, when you visit it) wrote to me about landscape. Landscape is central in Tamara's own books, she said, and having read Small Damages for BookBrowse, Tamara sensed that it mattered to me as well. A conversation ensued—deep and ranging, thanks to Tamara's smart questions—and I am grateful to be able to share the whole here, on Kissing the Earth.

A fragment:

KTE: You told me that, for

you, landscape is a character. It is for me too. Can you explain that a

bit here? Why is this so? How do you manifest this belief in your

work?

BK: Landscape shapes us.

It defines our legs and lungs as we walk through it. It shapes the

way we see, how we define horizons, what seems impossibly far away and what

seems gratifyingly or frighteningly near. Landscape is proximity, and it

is distance. It is another way of measuring time. And so, in much

of my work—the memoirs (especially my book about marriage and El Salvador), the

river book, a YA novel that takes place in Juarez, a YA book that takes place

in a garden (and Barcelona and Portugal), another YA novel that takes place in

Centennial Philadelphia, and of course Small Damages—I am placing my

characters down among very specific places and learning how it shapes them.

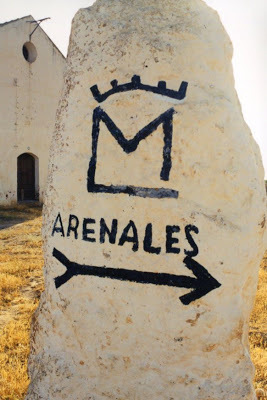

Tamara, thank you. The conversation was a privilege. Kenzie's landscape was inspired by Arenales, the cortijo I visited in southern Spain, among other sites. I am yearning, deeply, to return.

I was all set to post this link to my conversation with Tamara when that incredibly generous sneak, Serena Agusto-Cox of Savvy Verse & Wit, sent me a late-night email with a link that would not, she said, go live until today. Well. In my humble opinion, this blogger, wife, mom, and full-time employee (how she does it all, I do not know) has done so much for me and my books that I felt embarrassed to imagine that she had spent the time to read another Kephart book, and to reflect on it. When I read Serena's review of Small Damages, I felt even more—I don't know the word—for Serena clearly put so much heart and time and thought into her words. Perhaps she did this at 2 AM, or perhaps she did it on her lunch break. I don't know when, or how, but Serena, I am grateful.

Published on August 02, 2012 04:59

August 1, 2012

The Vaddey Ratner Interview: this is one you cannot miss

I have been driving poor Ed Nawotka, editor-in-chief of Publishing Perspectives just a tad crazy these days. (Sorry, Ed!)

Please can we run the Vaddey Ratner interview, I've emailed. Pretty pretty please.

My urgent requests being made despite the fact that Ratner's book, In the Shadow of the Banyan, will not be released for a few more days.

It's just this: Ever since I saw Ratner at the BEA during the adult buzz panel, I knew. I knew her book would be huge, and I knew Ratner (who in real life is a gorgeous petite) would be huge, as well. Banyan, a novel based on Ratner's childhood experience during the Cambodian conflict, isn't just lush and harrowing, infused as it is with both poetry and heartache. It is moral, compassionate, and electrified by a consonant humanity. Ratner stands for something good and right in fiction making, and here's what's so cool about that: the world is noticing. Her book has wings.

(For a small excerpt from the beginning, go here.)

Ed has given me the opportunity to interview a number of wonderful people in publishing (see the sidebar on this blog for links to former stories). I am grateful, Ed, that you gave me room for this long piece on Ratner. I asked questions by email. Ratner answered with great care. This, for example, is how the interview begins. Please read the whole of it here. It's about life. It's about writing. It's about hope.

You returned to Cambodia after many years away

and lived for a time within your country.

Can you recreate your first moments of return? What did you look for?

What did you find? Beyond

the return to the palace and the gift of rice, how did you spend your time

there?

The first time I returned to Cambodia was in 1992, thirteen

years after our traumatic escape from the country, the whole experience still very

much fresh and alive in my mind. Indeed,

parts of the country were still controlled by the Khmer Rouge rebels. While their regime had collapsed in

1979, they hadn’t completely relinquished their grip, terrorizing the

population with random abductions and killings and launching attacks against

the government’s forces. Thus, you

can imagine how my mother felt about my decision to return at this particular

time. “I risked everything to get

you out of there,” she said, her voice taut with love, and fear for my safety. “Now, you are going back.”

The last leg of that journey, the flight from Bangkok to

Phnom Penh, I remember, was full of overseas Cambodians, all of us on this joint

return to the homeland we couldn’t forget despite our desire for a new home, or

stop loving despite the bloodshed and brutality. At our first glimpse of Cambodia from the plane—the landscape

like a tattered tapestry patched with arid rice paddies and stitched together

by the flimsy threads of rivers and lakes during the dry season—we all simultaneously

burst into tears. Only the

beautiful young Thai flight attendants remained dry-eyed and composed, as if by

now well prepared for this kind of homecoming. They did everything they could to give us our dignity, as if

the entire cabin of passengers collectively sobbing aloud was nothing out of

the ordinary. I found this particularly

kind of them, for it allowed us to express, without shame or fear, our long

withheld sorrow.

Published on August 01, 2012 05:13

July 31, 2012

Small Damages: The New York Journal of Books Review

This late afternoon I extend my deep gratitude to Renee Fountain, for her thoughtful review of Small Damages in the New York Journal of Books.

I am honored to be in those pages. I am grateful to Renee for her understanding of Kenzie and of Kenzie's love for her unborn baby. Perhaps, as I told a friend not long ago, I was aching to write about maternal love when Kenzie stepped into my life. Perhaps I miss those early mothering years. It means so much when a reader makes room for the emotions I had as I wrote.

The review is sub-titled with the words below. The whole can be found here.

“Realistic . . . rendered in a quiet prose that speaks volumes.”

Thank you, Jess Shoffel, for letting me know.

Published on July 31, 2012 16:06

The BookPage interview, live

My friend Ed Goldberg sent me a note yesterday to say that a copy of the August 2012 edition of BookPage—the real, live BookPage—had appeared in his own library.

This made me happy indeed, for this issue of that fine magazine includes a conversation I had with the magnificent Abby Plesser, "Home is Where the Heart Is." I had received an early PDF copy of the story and had been able to share it on the blog, but I'm thrilled today to share the live link.

Abby and BookPage, I will always be grateful.

Published on July 31, 2012 02:26

July 30, 2012

Beth Goes All Rogue Silly, and A.S. King Catches It on Film

I don't know what it is about lately.

Truly.

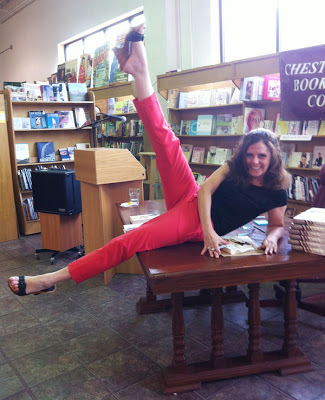

Ask A.S. King, that famous writer, She. She is the one took the photo here. Snapped it at Chester County Book and Music a few weeks ago, where I had gone to sign Small Damages, and where A.S. King and K.M. Walton and I practically shut down the little restaurant hours later. Or, at least, we shut down the lunch shift at 5 PM.

Minutes after striking this hot little pose I was informed by a quite polite but anxious management team that this very table had collapsed beneath another's weight, a few signings back. I wanted to ask if the other author had been a former Rockette, just like me, but decided to heed the caution and hopped off, pledging myself to adult behavior.

But here, forever, thanks to A.S. King, is me being me.

I will get back to my regularly scheduled seriousness on the morrow.

Unless another odd photo surfaces.

Published on July 30, 2012 16:09

The Jonah Lehrer Lies: But why?

Late last Friday afternoon, a client and I were discussing Jonah Lehrer. My client had seen Lehrer talk, we'd both read Imagine. We liked the provocative style of Lehrer's work, his easy translations of harder-concept things. We liked that a guy like Lehrer got so much attention in a Fifty Shades world.

But just today, a few minutes ago, I was checking out at the grocery store, when my phone buzzed. It was my client, sharing a link to this Josh Voorhees Slate story, titled "Jonah Lehrer Resigns From New Yorker After Making Up Quotes."

I raced home to read the story on the full screen. I churn now, within—confused, more than anything, as to why a young man as successful as Jonah Lehrer most certainly is would find it necessary, first, to fabricate Dylan for his book, and, second, to spin a complicated tangle of lies in the aftermath of being found out. Lie after lie. Preposterous lies. Not exaggerations, but lies.

Why do such a thing? Why cannibalize a rising-star career? Why jeopardize the faith of readers, an editor, friends? Writers make mistakes—we all do, I absolutely do—but deliberate deceit is hardly a mistake. Deliberate deceit is intentional, and designed. It can't feel good. Nothing will make it right.

There can only be, when lying as overtly as this, a terrible anxious rush in the middle of the night.

Published on July 30, 2012 14:45