Beth Kephart's Blog, page 139

March 15, 2013

Bisqued: progress images from the pottery studio

Remember that moment of deep frustration at the pottery studio? My angel Bernadette Stillo, or is she Saint Bernadette, continues to apply her steadying hand and good counsel. These two pieces have been bisqued. Yesterday we learned about glazing. I'm a little afraid to move from chalky pinkish white into shiny color. But I have a week to think about it.

In the meantime, check out Bernadette's own amazing work. I've been trying to figure out which piece to buy for some time now. :)

Published on March 15, 2013 04:56

March 14, 2013

In the Garden of Stone: The Susan Tekulve Interview

Not long ago I wrote here about how thrilled I was by a soon-to-be-released book winning early accolades—a novel by my friend Susan Tekulve called In the Garden of Stone. I was amazed by Susan's book, honestly. I respected, more than I can adequately articulate, her research, her care, her language, her adept way with southern legends and landscape. I asked Susan, an old friend (though she is younger than me and far more spry), if she would answer a few questions. She did. Read here to learn from a master.

In The Garden of Stone, images are handed down across the pages just

as family lore and land are handed down, character to character. What

image was pivotal for you as you began to think of these scenes

holistically—not as stories, but as a novel?

You are exactly

right to say that this kind of novel requires unifying elements beyond

the chronological retelling of a family story. This novel required

more, and different, unifying elements that a traditionally-structured

novel doesn’t necessarily require, such as recurrent images and

protagonists, and a strong sense of place. While each chapter could

exist on its own, together they must rest upon each other and have the

arc of a novel. I would say that the setting, particularly the image of

the Italian rock garden on the family’s home place, provides the key

images that unify the whole novel for me. In fact, the chapter,

“Italian Villas and Their Gardens,” was the most difficult to write

because I knew that every chapter before this one had to lead up to it,

and that every chapter that followed rested upon the events and images

set forth in this chapter. I knew the ending of the chapter before I

started writing it, and it is really difficult for me to write something

if I already know exactly what must happen. In fact, knowing the

ending of this chapter was so crippling that it took six revisions over a

course of six years to write it.

The “Italian Villa” chapter is

set in the depths of the Depression. You see Caleb Sypher, a

mysterious and imaginative man who is so desperate to create something

beautiful in this otherwise hardscrabble place that he builds a lavish

Italian pleasure garden from materials he barters for and collects down

around the railroad, where he holds down his paycheck job despite the

cutbacks. You see him instilling his love of beauty, his need to “have

more than what we have,” in his wife, Emma, who comes from a family of

Sicilian immigrant miners who spend all of their days under the earth,

in another kind of stone garden, barely remembering sunlight, let alone

the beautiful gardens of their home country. Emma comes from a place

that darkens by midday, and remains covered by oily coal dust all year

long. There wasn’t much opportunity for thoughts of beauty in her

childhood, but she learns about it, eventually, through Caleb.

Then, in

the middle section of the book, you see some of the second-generation

characters fall tragically from this garden, while a few other

characters, like Sadie, remain on the periphery, admiring it from a

distance. In this second section, no matter what their previous

relationship to this land was, the main characters all try to make their

way back to this garden, and claim it. Finally, in the third section,

you see the Italian pleasure garden fall into disrepair as the final

generation of characters try desperately to hold onto the land, or, in

some cases, escape from it. I didn’t necessarily think of the

garden as a unifying element while I was writing this book, but the

stone garden appears in every chapter, in various forms. This image

turned out to be the unifying thread that “stitched” the chapters

together.

Your love for this landscape and your knowledge of it awes me. Tell us a little of where you have walked, what you have

seen, how the mountains move you, how you learned the names of trees,

birds, flowers, ridges, bear seasons.

For the last twenty years, I

have been lucky to live about a half hour from the gateway mountains of

Western North Carolina. I’ve also been very lucky to know people who

are willing to lend me their cabins, camp houses or their guest houses

up in these mountains when I need to escape the palaver, as Thoreau

famously called all those daily things that distract us from truly

seeing and thinking straight.

I will say that my novel’s main setting

is based upon my in-law’s home place up around Bluefield, Virginia, but

when I couldn’t make the trip back to Virginia, I would stay at some

friend’s place up in those North Carolina mountains, where the terrain

is very similar to the mountains surrounding my in-laws’ home place.

Twice, while writing the book, I was able to live in the mountains for

an extended period of time. The first time, I lived in a friend of a

friend’s guesthouse up on Wilderness Road in Tryon, a tiny town kettled

between two mountains just across the border, in North Carolina. The

original owners had named this guesthouse “The Cold Potato,” after some

half-remembered bluegrass song. Beside the guest house, there was a

century-old Cherokee game trail that had been re-blazed by a homesteader

who lived in an old chinked log cabin beside the river that wound

around the bottom of the ridge I lived on. This homesteader allowed me

to walk the game trail and along the river that ran through a valley

that was planted with tomatoes. I lived in The Cold Potato in early

spring, so I was able to watch the spindly tomato seedlings grow into

full-sized tomato plants. As late spring came, there were times when I

teetered dangerously over rattle snakes that the tomato farmer would

kill and lay across the road so that I would know that the snakes were

in those fields, eating tomatoes. Because the trees hadn’t greened

completely, I was able to observe how wild turkeys resemble patches of

swirling dried leaves as they run up a late-winter ridge. I learned

that the black bears, crazed by hibernation hunger, will come down from a

high ridge encroached by land developers to tear off the lid of your

trash can, drink the dregs of your tossed out Coke cans, or lick the

cherry pie filling from the bottom of a tin pan. I learned what a bear

smells like, too.

I spent several years writing this novel

piecemeal while working full time, and mothering full time, but as I

neared the end of writing this novel, I took an unpaid leave from my job

so that I could finish it. A friend lent me her 1917 camp house that

stood at the base of the Seven Sisters Mountain range, in a little town

called Montreat, North Carolina. Montreat is a spiritual retreat center

that was settled by Scottish Presbyterians in the late 19th century, so

this place resembles a lower highland village in Scotland. There are no

sidewalks here, just hiking trails that lead from the front doors of

everyone’s houses and border a quiet stream called Flat Creek. The

creek crossed through the town center, which is really just a small lake

named, almost providentially, Lake Susan. When I went to live in this

place for the whole month of September, I had the idea that I would let

this mountain landscape work on me as I finished the novel. I began

writing the end of the book by walking in the woods. First, I followed

Flat Creek down to the lake, where I discovered that the gorgeous swans

that patrolled the lake were the least elegant creatures on this earth

when viewed up close. They snort like hogs. They tip over, rumps in

the air, snaking their beaks underwater to swallow whole frogs. When

they tip back over, I could see the frogs slowly struggling down the

inside of the swans’ snowy necks. After pausing at the lake, I hiked up

to the nearest trailhead that branched off into the “lower trails,”

which, I learned quickly, were once wilderness trails that reached

elevations as high as 5900 feet.

After a few days of hiking, (and

heaving), along “the lower trails,” I began to learn how to remain

quiet, and how to pay attention. I discovered that falling acorns sound

like gun shots when they hit a tin roof, and that clouds rise like

delicately twisting handkerchiefs from black ridge pockets after a storm

passes. I learned that black bears are real comedians. If you remain

still and watch them from a safe distance, they will come out at dusk to

swing on the limbs of the apple tree growing beside your kitchen

window. They’ll balance delicately, on all four paws, on top of your

bird feeder and scoop out all the bird seed. And if you are sitting

beside a window at dusk, reading, you might look up and see a doe

staring in at you, taking your measure, so close you can see the veins

inside her ears. If she likes the look of you, she’ll bring back her

fawns the next night so that you may admire them. I don’t mean to sound

like Henry David Thoreau’s direct descendent here, but I did go to the

woods so that I could learn how to see and hear, and so that I could

write without distraction. I finished the last third of the novel in

this setting, in exactly one month.

Coal mining. Herbal

healing. The madness and methods of self-educated cooks, farming lore.

How did you teach yourself so much about indigenous process?

I

should start by saying that I am not a trained natural scientist. I

grew up roaming in the wooded hills of my earliest neighborhood just

north of the Ohio River, and to this day a wooded landscape is where I

feel most at home. As an adult, I learned the proper and folk names of

the trees and flowers I saw while hiking in the woods. I also came to

know the ridges and bear seasons down here in the Carolinas and in

Virginia. I do use reference texts about herbs, wildlife, Appalachian

wildflowers, Cherokee trail trees. The Foxfire books are an especially

important resource for me. I keep these books close by when I write

because they feature transcriptions of oral accounts by Appalachian old

timers who knew everything about staying alive on the remote side of a

mountain, from moonshining skills to snake lore, from planting by the

signs to making nostrums from the herbs and flowers they picked.

But,

like most people, I have an innate need to seek out places that resemble

the landscape of my childhood because that is where my emotional

landscape was formed. Another way of saying this is that even when I’m

writing about a place and a people who are seemingly different from my

own experience, I’m often still working through some basic emotional

truths that I haven’t quite figured out, and I often will return to a

place that resembles my early emotional landscape—whether it is the

Southern Highlands or a village in Italy--in order to do this. Though I

do a lot of book research, I also have found that I need to live with

those researched details until they become a part of who I already am,

so that I’m not just dumping information into my fiction, and so that

the details remain in service to the story that I am telling.

You

dedicate this book to your mother-in-law, and you speak of interview

tapes made for you as you wrote. What two or three true things made it

into this novel? What alchemy did you learn or apply as you transported

the truth into fiction?

I guess there were really three women

whose true stories influenced this novel—my maternal grandmother, Joy;

my great aunt, Grace; and my mother-in-law, Mary. My grandmother was a

rheumatic invalid’s daughter who was born after her mother was already

in a wheel chair; she never saw her mother stand or walk, and she was

taken out of school when she was seven to be her mother’s full-time

caretaker. She never spoke of this part of her life to my mother, and

she died when I was young, so my mother and I figured those details were

lost to us. Then, in my late twenties, my great aunt Grace, (who was

really my grandmother’s first cousin), began tape-recording stories

about my grandmother’s early life and mailing them to me in South

Carolina. The tapes she sent were all labeled “Stuff your mother never

knew about your grandmother.” I think I received one tape every month,

for a whole year. Ending around the time my mother was born, Grace’s

stories were finely detailed, anecdotal. She fleshed out the true

details of how my grandmother lived as an invalid’s daughter in a

neighborhood north of the Ohio River called Winton Place; how my

grandfather, who was ten years younger and an “Italian Catholic boy”

from the river bottoms, courted her for years, finally becoming a

teetotaler and Methodist so that my grandmother would marry him; how

they all got through the Depression and World War II. I knew I wanted to

use these details in a book about my family, but I wasn’t sure how to

find my way into this story. I felt a huge disparity between the girl

my Aunt Grace called Joy, and the woman I knew as my grandmother. I

felt no great emotional ties to the river bottoms, where my Sicilian

grandfather grew up, perhaps because that area had been cemented over by

the time I was growing up north of the river. And when you don’t feel a

strong emotional tie to the setting of your story, it’s hard to make

your story move forward.

Around the time I was struggling to make

narrative sense out of my own family’s stories, I went to live with my

husband, Rick, at his family’s home place in Bluefield, Virginia. Rick

is a poet, and he had the idea that we should go live in his

recently-deceased grandmother’s house one summer so that he could

research a series of poems that emulated the sounds of bluegrass music.

While he researched bluegrass music for his poetry, I came to know my

mother-in-law, Mary, through the stories she told me in her kitchen. In

my memory, I always see and hear Mary in those evening hours in her

kitchen, a mountain breeze blowing her dishtowel curtains in and out of

the window above the sink. A quiet woman with knowing brown eyes, she

spoke with the cadence of the King James Bible trembling her soft voice.

My father-in-law always said that Mary’s early upbringing was so rough

that the details of what happened to her as a child in that trailer

could not be repeated. Though she hardly ever spoke of her childhood

directly, Mary’s stories often involved quietly strong women who faced

the unendurable—pain, violence, poverty—and triumphed. This was one of

her favorite stories: “When I was seven, I used to walk eight miles up

the mountain to fetch my baby brother a cup of milk from our nearest

neighbor,” she’d say. “I did this every morning and every evening, just

so the milk would be fresh.” Then she’d smile, quietly pleased by the

memory of keeping her brother alive by carrying a tin cup full of milk

down a mountain.

Sometimes, Rick’s father, Larry, would drive me

around, acting as tour guide, telling me stories about his family. One

day, he drove me down into West Virginia to see the abandoned coal

camps, and he took me on a tour of an exhibition coal mine in

Pocahontas, Virginia. While we were in Pocahontas, we walked through

the town’s graveyard, and I noticed that one whole side of this cemetery

was filled with tombstones whose epitaphs were written in Italian.

After doing a little research, I discovered that the coal companies

would send representatives to meet the immigrants coming off the boats

at Ellis Island, promise them jobs, and then take them down to the

deepest hollows of West Virginia to work in the camps. The more I

traveled around this part of Southwest Virginia and West Virginia,

listening to the stories of my husband’s family, the more this place and

its people resonated with me emotionally. It is a place of tremendous

natural beauty, and a place of tremendous economic and cultural strife.

The fact that Southern Italians and Sicilians had settled here was a

revelation to me, and it introduced the possibility that my Sicilian

grandfather’s people could have landed in a Virginia coal camp just as

easily as they had settled beside the Ohio River. Because I felt more

of an emotional connection to the natural landscape in Virginia, and

because it is a place filled with conflict and contradictions, it began

to make better narrative sense to place the stories of my grandmother,

(as told to me by my Aunt Grace), in this one place.

Once I discovered

that this was my setting, my brain began performing that fictional

alchemy you spoke of in your question; I started mingling the story of

my grandmother and my Sicilian grandfather with the stories of my

husband’s family, and the novel began to move forward. The novel is

really the distillation of my family’s stories and Rick’s family’s

stories, all set in one place, and it is this place that unifies the

novel and provides much of the conflict that forces it to move forward.

The two women who told me many of the stories that this novel is based

upon—my great aunt Grace, and my mother-in-law, Mary—died while I was

finishing this book. I still believe this novel was a gift, its details

given to me by these women, the finished version written for them,

their strong voices leading me all the way through it.

Published on March 14, 2013 14:02

March 13, 2013

that boy I have always loved so much has a full-time offer in his field

I was this young once. So was he.

He grew up. He went to the school of his dreams. He fell in love with a certain discipline, a subset of advertising I have yet to understand (statistics are involved, creative research, analysis and ideas), and traveled to Europe to learn more, earned three internships, kept his finger on the pulse of this thing.

Sent out resume after resume, as one does. Had nearly two dozen interviews.

Today he received an offer to do precisely what he wants to do.

There is so much dance in his voice. So much joy.

Mike Yasick, you who cared so much about this kid. Are you up there, pulling strings?

What a very bitter and very sweet week this is.

Published on March 13, 2013 14:07

my city in lights

Published on March 13, 2013 08:06

March 12, 2013

Graphic the Valley/Peter Brown Hoffmeister: Reflections

A book is sent to me and joins the piles of the so many books sent. (Many books sent.) In the overwhelm, I slide sideways toward this book with its sketched cover, its title Graphic the Valley (Tyrus Books). It is by a climber named Peter Brown Hoffmeister. It is, I read on the back cover, a Samson and Delilah story, a story about a young man named Tenaya who "has never left Yosemite Valley. He was born in a car by the Merced River, and grew up in a hidden camp with his parents, surviving on fish, acorns, and unfinished food thrown away by the park's millions of tourists. But despite its splendor, Tenaya's Yosemite is a visceral place of opposites, at once beautiful, dangerous, and violent."

I open and begin to read:

I'd slept against the bear box, the iron food cache cold through my sleeping bag, and woke when it was dark. I couldn't sleep a night without picturing her, eight years after, the way she lay against the river boulder, her right hand turned away, fisted, like it held a valuable.

I choked on nothing and sat up.

Wait, I think. Read more.

Low clouds hung in the Valley, the ends torn as wet paper....

The Valley rolling its shoulders, ten thousand years, after the final ice receded, boulders sitting as terminal moraines, the chambers of the ancient volcano exposed in white-and-gray plugs, flakes weakened by freeze water and the sloughed granite crashing, the Domes shrugging awake....

The drifts harbored the mosquito hatch, so I used bank mud as a face coat. But the granules dried by midnight and the mosquitoes came up my nose before that....

It is late, and I read. It is early morning, and I read. I have entered, I realize, the realm of a man who knows landscape and bear scat and mountains lions and native legends, the interiors of hitchhiker cars. Also a man who is inventing language. I think of James Joyce, and I don't know why, because Joyce was not (to my knowledge) a big boulder climber. (Am I wrong?) Joyce did not live in Yosemite.

What's going on here? It's hard to know precisely at first, but that's part of Hoffmeister's method. He is no spoonfeeder, this writer. He has no time for, no patience with, commonplace storytelling, obvious frames. We're in Tenaya's head, and Tenaya is sliding all around time, not stopping to make careful asides to the reader, not giving us the old coy wink-wink. He's letting the world drift in as he sees it, memories float toward as they occur, that long, thick braid of dense, dark hair snake its way toward the ground.

In time this invented language becomes a familiar language and the story becomes clear. In time we understand that this is a possession story and an anti-possession story, a tale about control. Big Money is poised to build motels and burger shops into that pristine valley. Tenaya—a young man without so much as a birth certificate, a young man who has never left the valley and yet has no rights in it—must find a way to save what he loves.

Can he? Hoffmeister makes us eager to find out, makes us love that valley, too, love his noble, mythical Tenaya, love the stars that shine at night. He's a remarkable writer, this Hoffmeister, but he's not an easy one. Easy doesn't interest him. And I am glad for that.

One last passage:

Sometimes I tried to count the stars in a small section of sky, a box between any four constellations. But not on a night like this. In the high dark, the stars procreated like white flies, their new young filling spaces, exponential sparkling.

I told stories to Kenny.

I was arrested two nights later.

Published on March 12, 2013 07:04

March 11, 2013

a Philadelphia photo essay, in the Inquirer

The days are rarely what we imagine they will be. The news comes in. The shock. The losses. Ordinary days, as my friend Katrina Kenison has written, are, often, the greatest gifts of all.

One of the greatest gifts I've been given in recent months is the chance to write an occasional piece for the Inquirer—pieces about the city I unashamedly love. I don't write journalism, don't know how. I just write my heart. And I take my camera out there, too, because sometimes my lens writes the stories better than my handful of words.

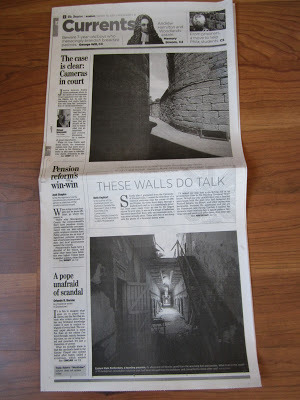

This past weekend I was blessed by the publication of a photo essay about that part of Philadelphia once known as Bush Hill. I wrote about my travels through that area years ago and the revival of Eastern State Penitentiary.

You can write all you want, take whatever photos cross your path. It's nothing without an editor and a designer. And so today I thank Kevin Ferris and his team for the layout that they chose for the front page of this past Sunday's Currents section.

Published on March 11, 2013 07:17

March 10, 2013

why not be kind?

I sat in church remembering my friend Mike Yasick. I thought about the thousands of people searching for one last conversation with him, for a moment with him, for a chance to say goodbye. Thousands of people because Mike was that kind of guy. He brought sun into a room. He demonstrated, repeatedly, why it is far more rewarding, in this life, to be a force of good. Negativity is all sharp edges. Unprovoked cruelty solves no problems. Unkindness is unkarma. Why throw spears when there's a bowl of chocolate near? Why not slice the thorns off roses? Why not laugh? Why not make somebody happy?

Are you superb?

As I sat there thinking about Mike, Miyuki Hoshimoto, a gorgeous soprano, sang "Agnus Dei." I watched her, but mostly I watched the other members of the choir, their faces tilted at angles, their heads rising and lowering with the notes. That, I thought, is what unburdened generosity looks like. It is the shape of appreciation, when envy will not float. There was the beauty of the song; there was the beauty of those who listened.

It was a necessary appeasement on a day when so many mourn the loss of a significant good.

Published on March 10, 2013 09:13

March 9, 2013

mourning the loss of the truly great Mike Yasick, the head of Shire Specialty Pharma, and a friend

March 6, 2013, 8:25 AM, the email zings in: "Are you superb?"

It was from Mike Yasick, of course, head of Specialty Pharma at Shire—one of the only people on this planet who regularly addressed me with that kind of jazz. He was like that, Mike Yasick. He was light. He was a serious guy, sure, a well-read guy, a guy who loved his family and a guy who loved his job. But he was also a guy who made us laugh.

"Hey," he said, last time we were talking on the phone. "You want to see how dumb I look in bright red pants?"

"Sure, Yasick," I said.

"Check your in-box," he said.

And that, above, was the picture he sent.

Mike Yasick knew what it was to live a life. He knew that the clock was ticking on his own—that he had inherited a difficult disease, that it could flare at any time, that his own father and brother had been taken too soon. He wanted to live fully—and he so absolutely did. Taking his wife around the world to celebrate her birthday in style. Sending colorful notes to friends during his Vietnam travels. Watching one daughter dance, another daughter take her first huge job, a son prepare a favorite meal with chef-like precision. Not just watching. Watching is the wrong word. Mike Yasick appreciated every single second of those he loved. He appreciated his life, and when you were with him, when you thought of him, when he showed up at your birthday party and said, "I love your Dad, he reminds me of my own," you appreciated your own life even more.

I talked to Mike because I wrote stories for Mike—that's what I do for Shire. He'd joke that I never gave him enough ink. "Don't you want to use my picture?" he'd say, stopping me in the halls. "Don't you want to quote me on something? Aren't I important? Don't you think I am?" I'd indulge him when I could. But mostly I'd just stop to talk, or he'd email me, or he, on occasion, would call. "You in?" he'd write, and I'd say, "Sure, Yasick, I'm in." And then the phone would ring and he'd make me laugh, but he'd make me think as well.

Not long ago—maybe nine months ago—the conversation grew serious. He was worrying about work things. He was pondering this condition of his. He was saying how much he loved his wife and family, how much he wanted to beat the odds of his genetic inheritance and stick around a long time. "Don't you go anywhere on us, Yasick," I said. And he said, "I think you're going have to deal with me for at least a while more."

I wanted a lot more while. We all wanted a lot more. I mourn the loss of Mike deeply. I mourn for his wife and children and family and fishing friends and thousands of colleagues at Shire. He left an impression. He made a difference. I'll hear his laugh in my head a long time on, will miss him asking what books I'm reading, will miss him saying, "You've become someone, haven't you?"

Am I superb? Not today, Mike. Not with this news. But I know the sun is shining out there right now because you're up there in the skies.

Published on March 09, 2013 12:03

Mary Coin/Marisa Silver: The Chicago Tribune Review

In today's Chicago Tribune I'm reviewing Mary Coin , the new novel by Marisa Silver. The piece appears in Printers Row, the Tribune's truly comprehensive (and always intriguing) book coverage that can be received digitally for a low annual subscription fee.

I share the first two paragraphs of the review here:

A photograph, Marisa Silver writes at the end of her new

novel, is “an alchemy of fact and invention that produces something

recognizable as truth. But it is not the truth."

It is as if Silver is writing about her own new novel

here—about the melding of history and imagination, probability and conjecture

that frames Mary Coin. The story

turns around the iconic Depression-era photograph known by most as “Migrant

Mother”—that young mother in a roadside tent, those distance-seeking eyes,

those two dirty children snuggling away from the scrutinizing thievery of the

camera’s lens. “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children.

Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California.” That’s the caption you’ll find if you search

for the photo on the Library of Congress site. And then you’ll find this

explanation, written by the photographer herself, Dorothea Lange.....

Published on March 09, 2013 03:37

March 8, 2013

The Diary of Pringle Rose/Down the Rabbit Hole/ Chicago 1871: Susan Campbell Bartoletti

Back in August 2011 I posted here under the title "How great is Susan Campbell Bartoletti?" I reported on how this award-winning writer for young adults had saved me in Orlando, FL, just ahead of an ALAN panel (we shared the dais; she mastered the technology; she made people laugh; I spoke, sorrowfully, of a massive fire). Later I wrote of Susan's kindness in driving many miles to appear in the Young Writers Take the Park event I'd orchestrated with The Spiral Book Case in Manayunk. And then one day I made a video for Susan and her Penn State students, about the crafting of dialogue in two of my novels.

But my very favorite Susan BC moment remains that August day in 2011 when we sat in a top-floor room of the Kelly Writers House on the Penn campus talking about our mutual love for 1871. Yes. Truly. How many people will I ever meet who will love that year as much as I do? Susan was deep into writing her Diary of Pringle Rose for the fabulous and famous Scholastic Dear America series (if you want to know how fabulous, here is Taylor Swift talking about the impact the series had on her). I was finishing my prequel to my Centennial Philadelphia novel, Dangerous Neighbors—a boy's adventure, an 1871 Philly story, due out in early May called Dr. Radway's Sarsaparilla Resolvent. In the cool shadows of Kelly Writers House Susan and I spoke of fires and trains and schools and prejudices, about classified ads and research. We will forever be bound by friendship and a year, by an afternoon at Penn.

Early this morning I had the great pleasure of reading Pringle Rose's story, which is secondarily titled Down the Rabbit Hole and was officially launched a few days ago. It's a pure pleasure of a read; it's vintage Susan. It's a story that takes its fourteen-year-old heroine out of the coal mining country of Pennsylvania (where Susan herself lives) and toward Chicago during a hot, dangerous summer. Pringle has lost two parents to an accident she doesn't quite understand. She has a brother, Gideon, who is different and lovable and deserving of her care. She boards a train with her brother in tow and believes herself destined for a new and elevated life. But the past catches up with these brave journey-ers. And then there's the heat of that summer, that devastating heat, that will crescendo to the Great Fire of Chicago.

Scholastic knew what it was doing when it invited Susan to write this Diary, and I am confident that it will now reach countless thousands—reach, entertain, and enlighten. Susan and I are nursing a fantasy that we'll have an 1871 Celebration Day together. Between now and then, I'm celebrating her.

(The photo above, by the way, is the street where my own 1871 character William lived. I'm still trying to figure out a way to get William and Pringle together.)

Published on March 08, 2013 06:27